Development and Characterization of Clindamycin-Loaded Dextran Hydrogel for Controlled Drug Release and Pathogen Inhibition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Dextran Hydrogel

2.2. Optimization of Crosslinker Concentrations for the Synthesis of Dextran Hydrogel

2.3. Water Absorbency and Swelling Behavior of Dextran Hydrogel

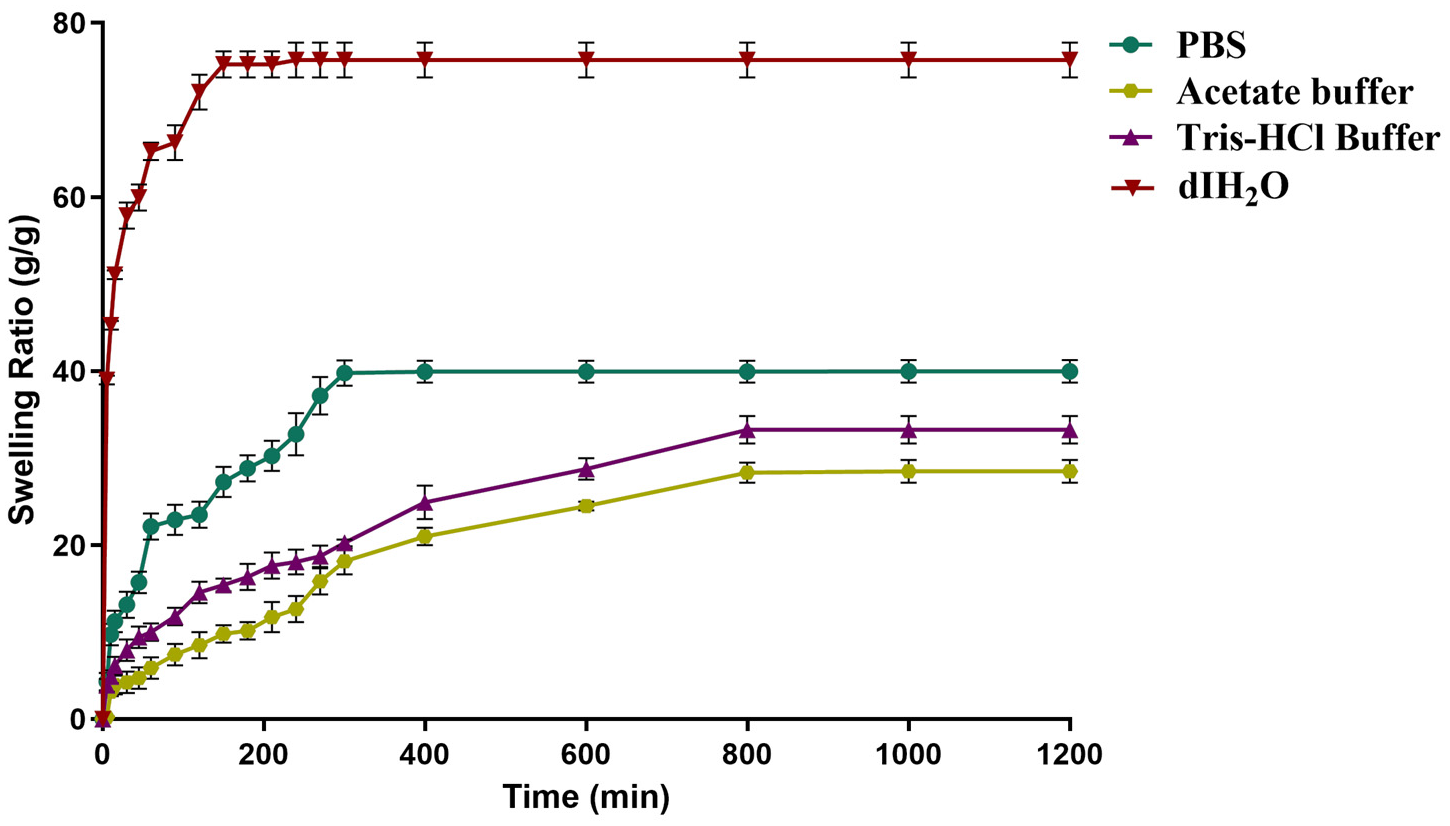

2.4. Effect of Buffer on the Swelling of Dextran Hydrogel

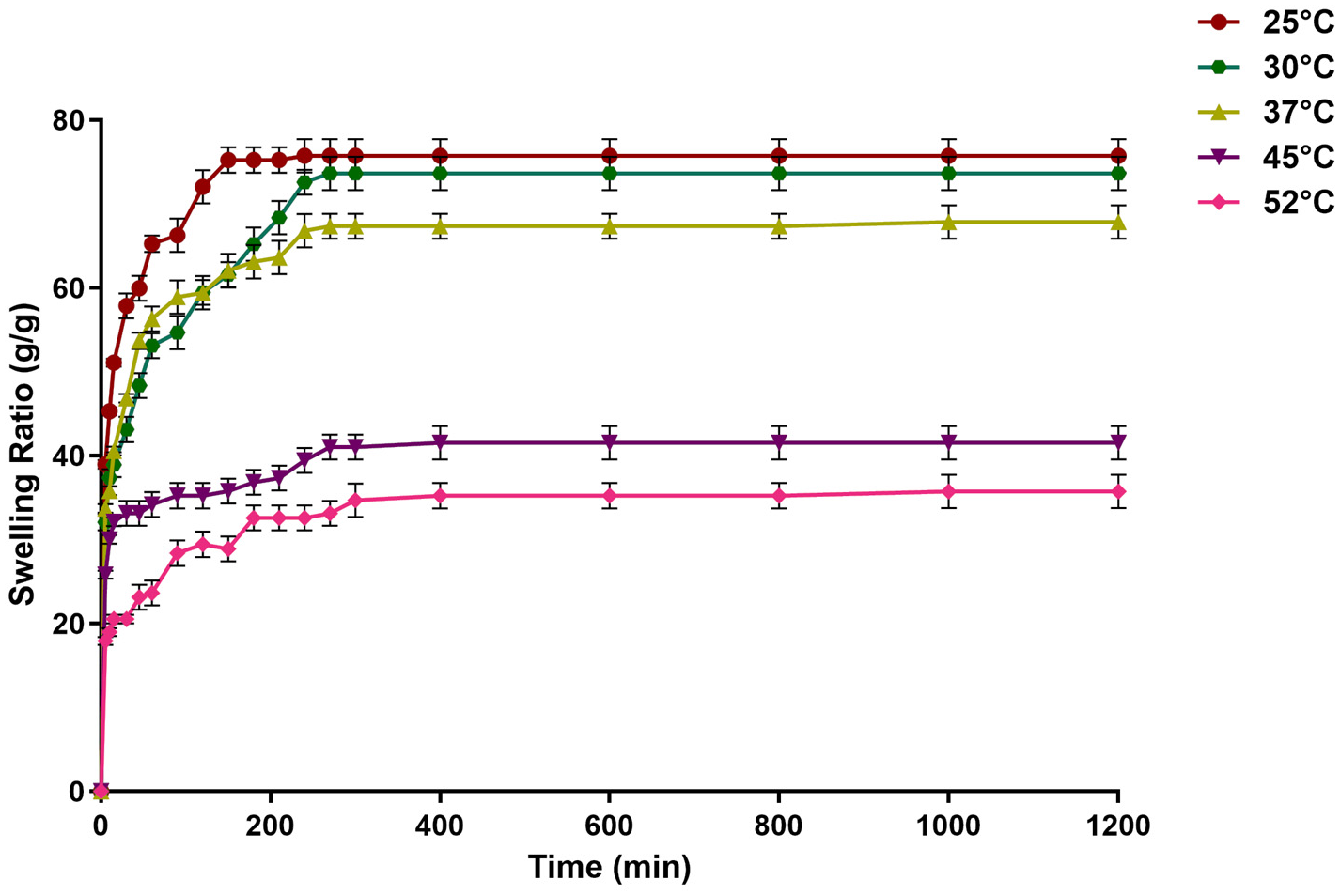

2.5. Effect of Temperature on the Swelling of the Dextran Hydrogel

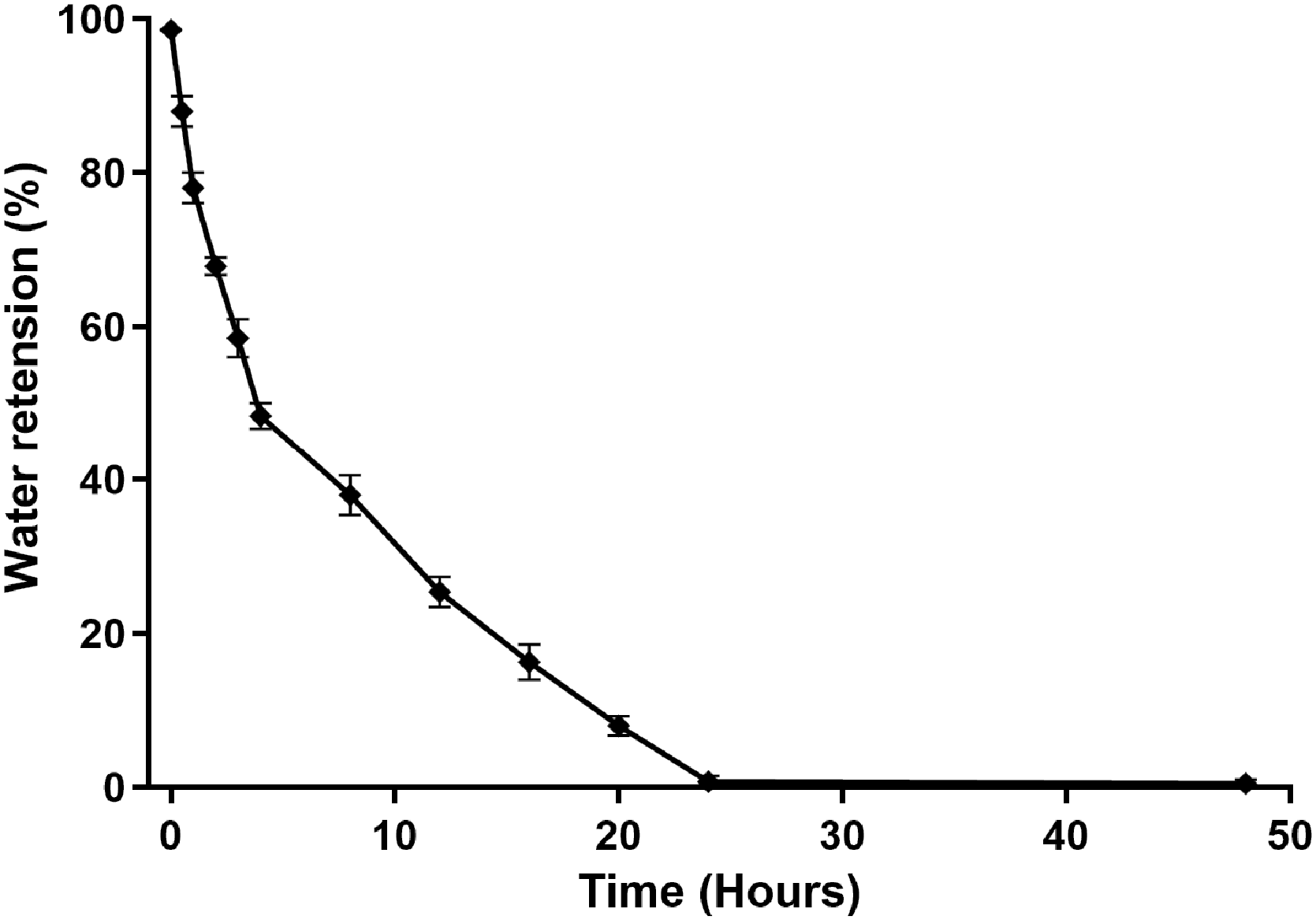

2.6. Deswelling and Water Retention Capacity of Dextran Hydrogel

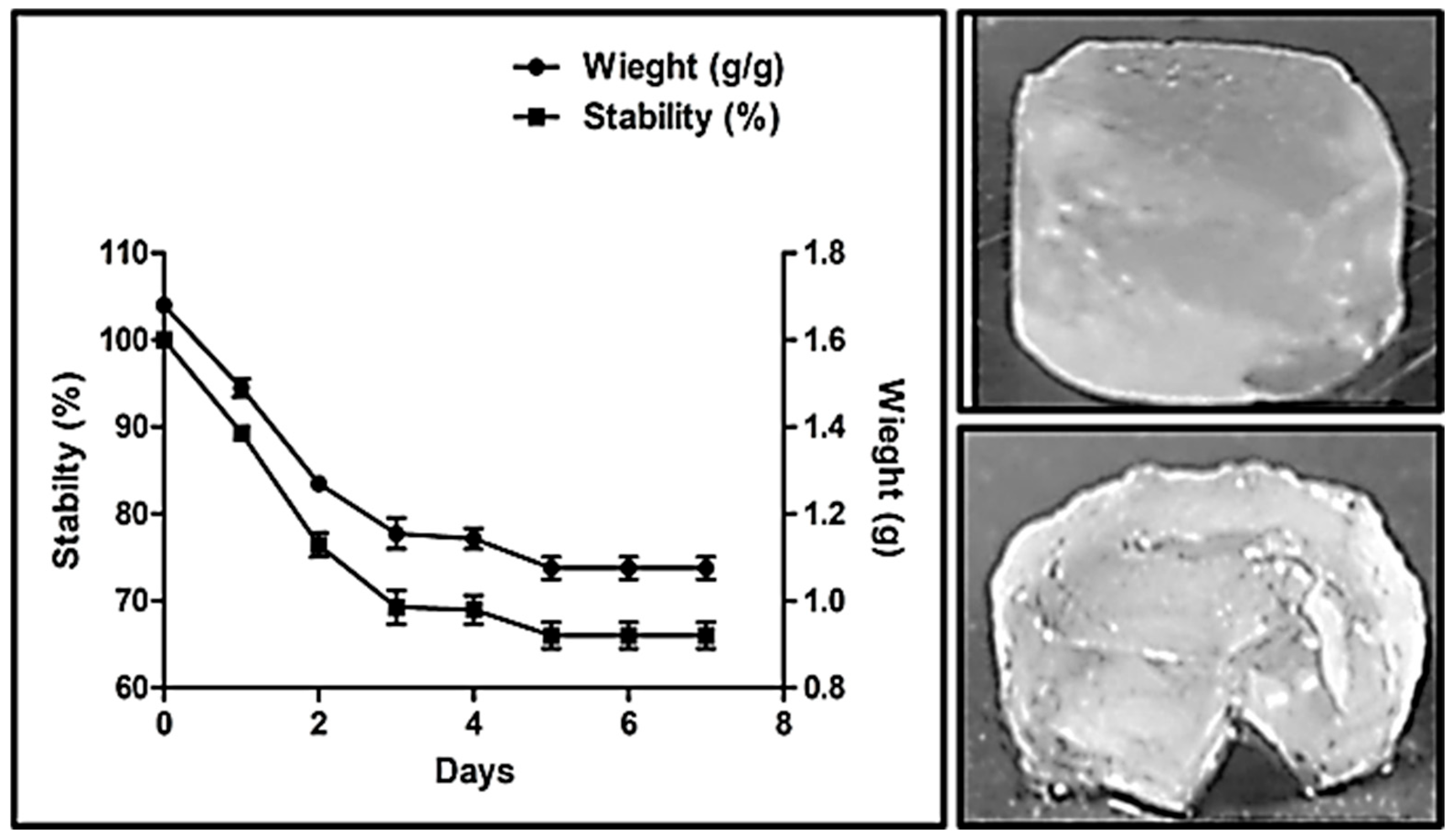

2.7. Stability Analysis of Dextran Hydrogel

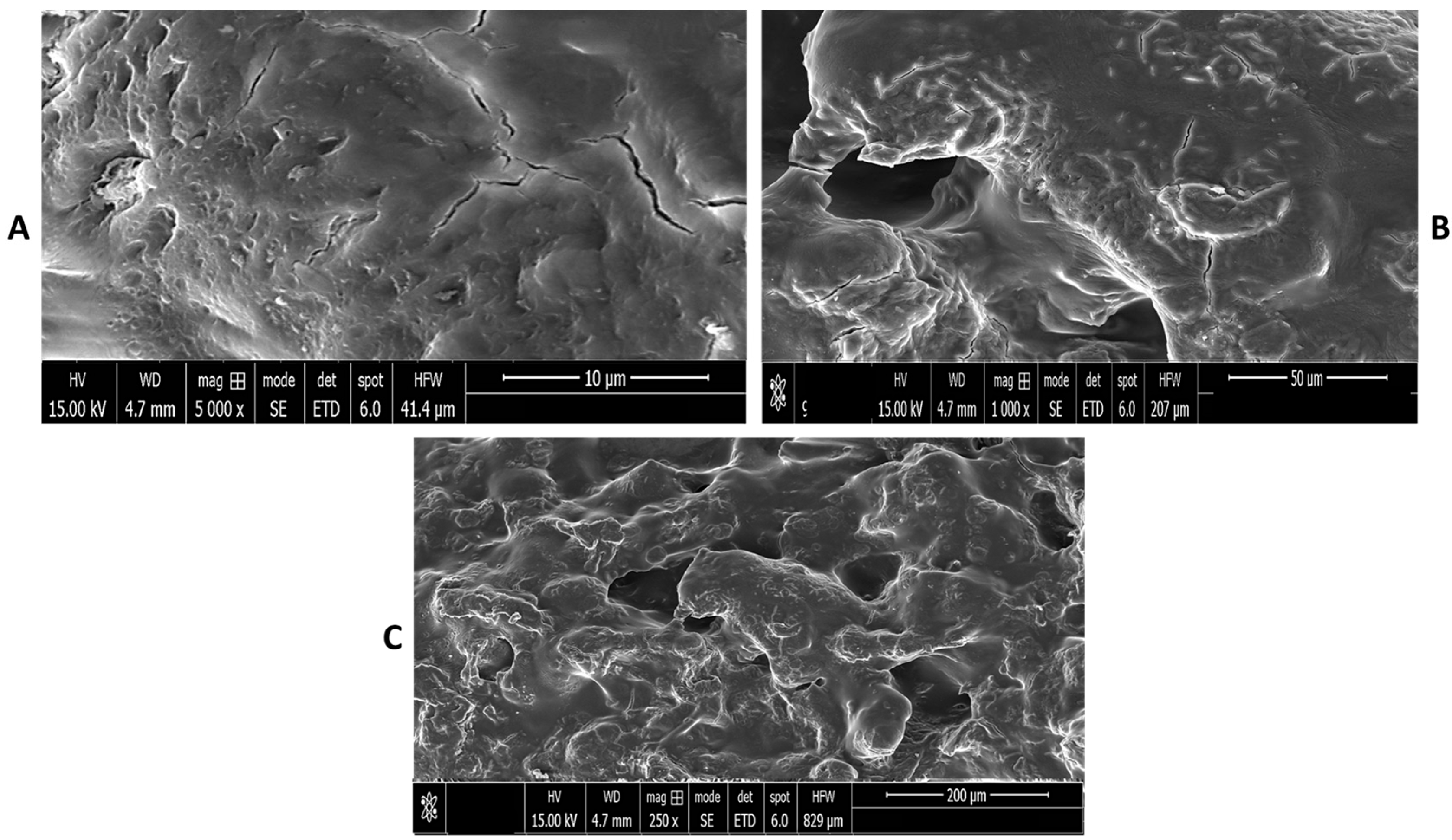

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

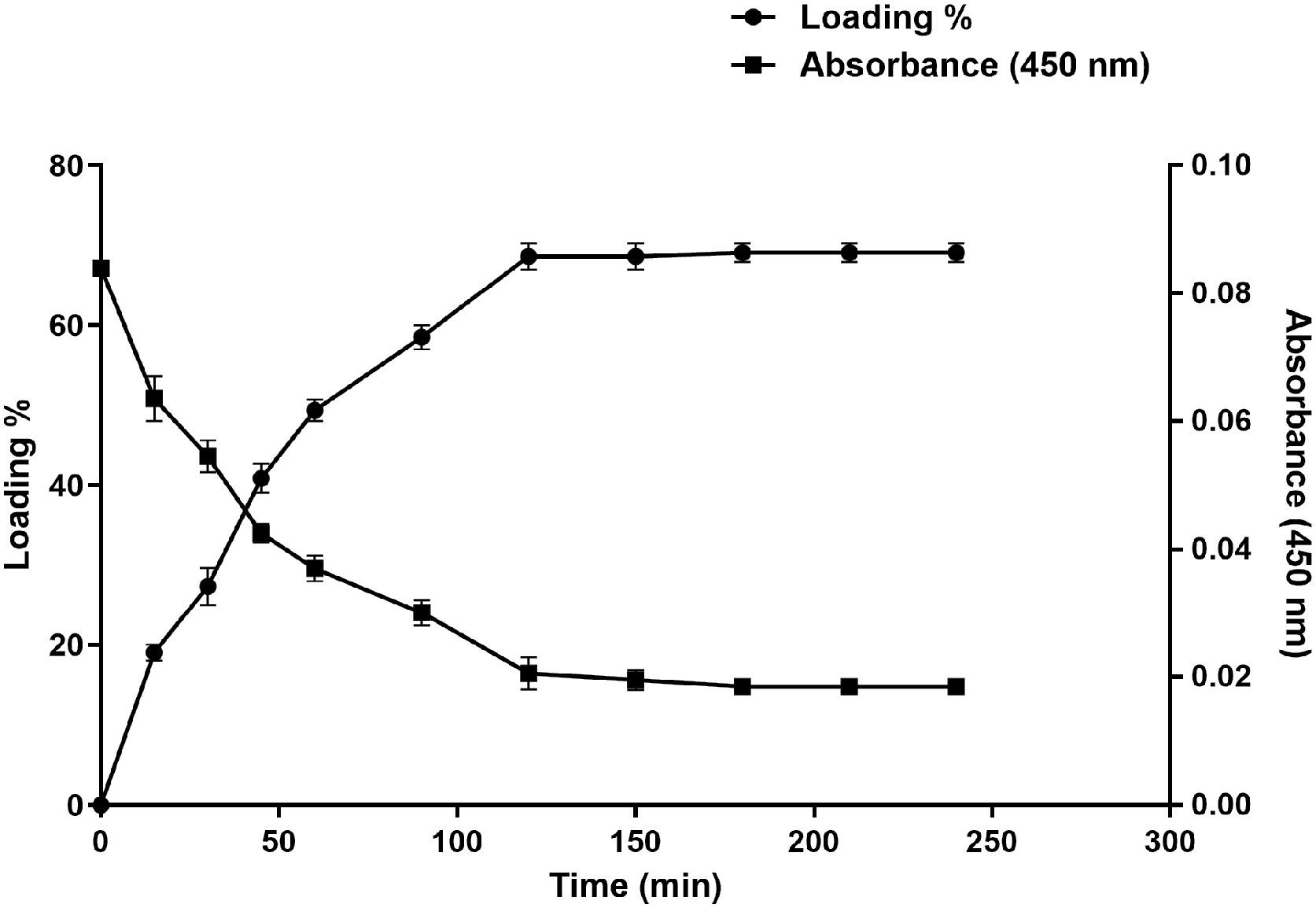

2.9. Drug Loading Studies

2.9.1. Estimation of Clindamycin Loading Capacity in Dextran Hydrogel

2.9.2. In Vitro Drug Release Analysis

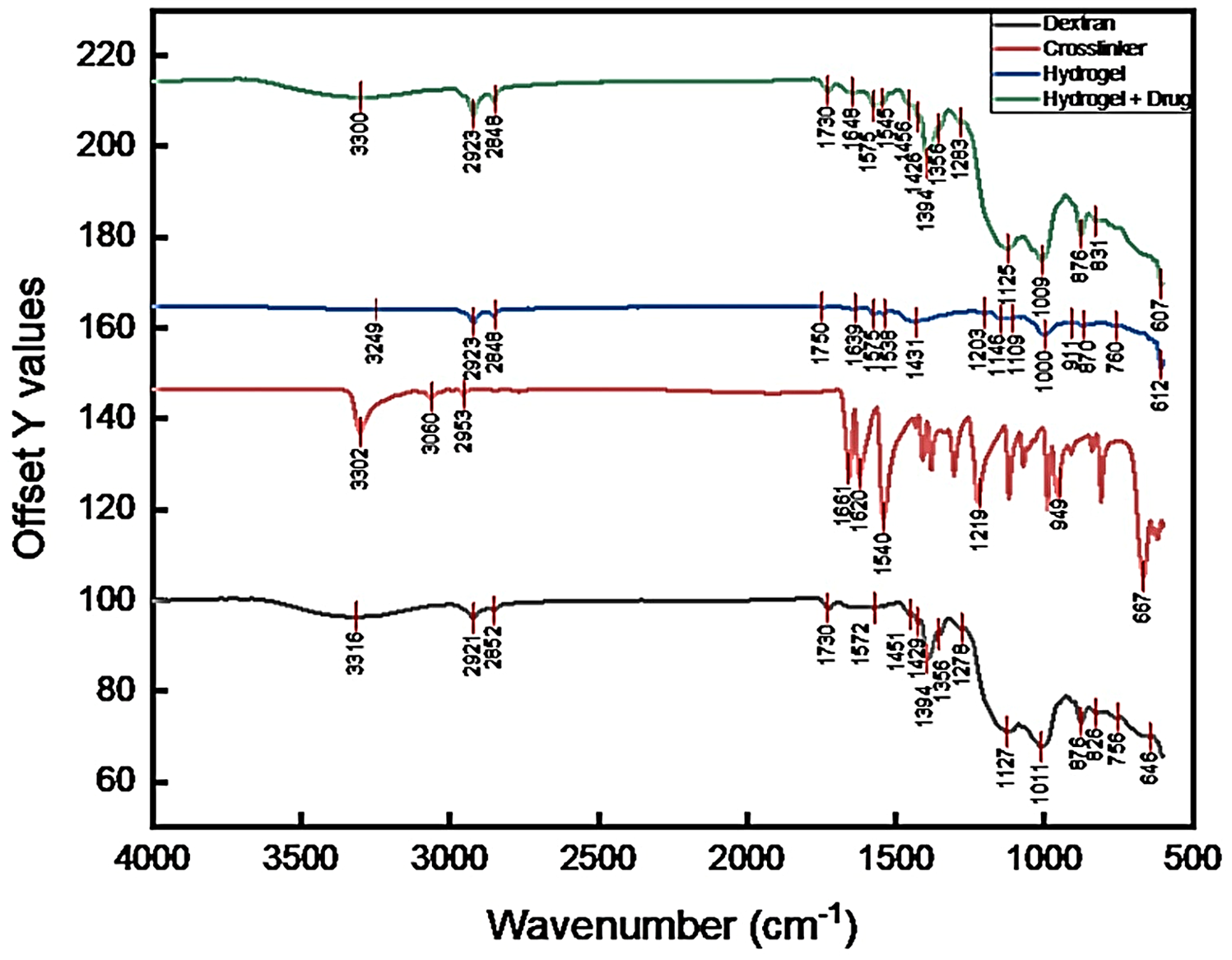

2.10. FTIR Analysis

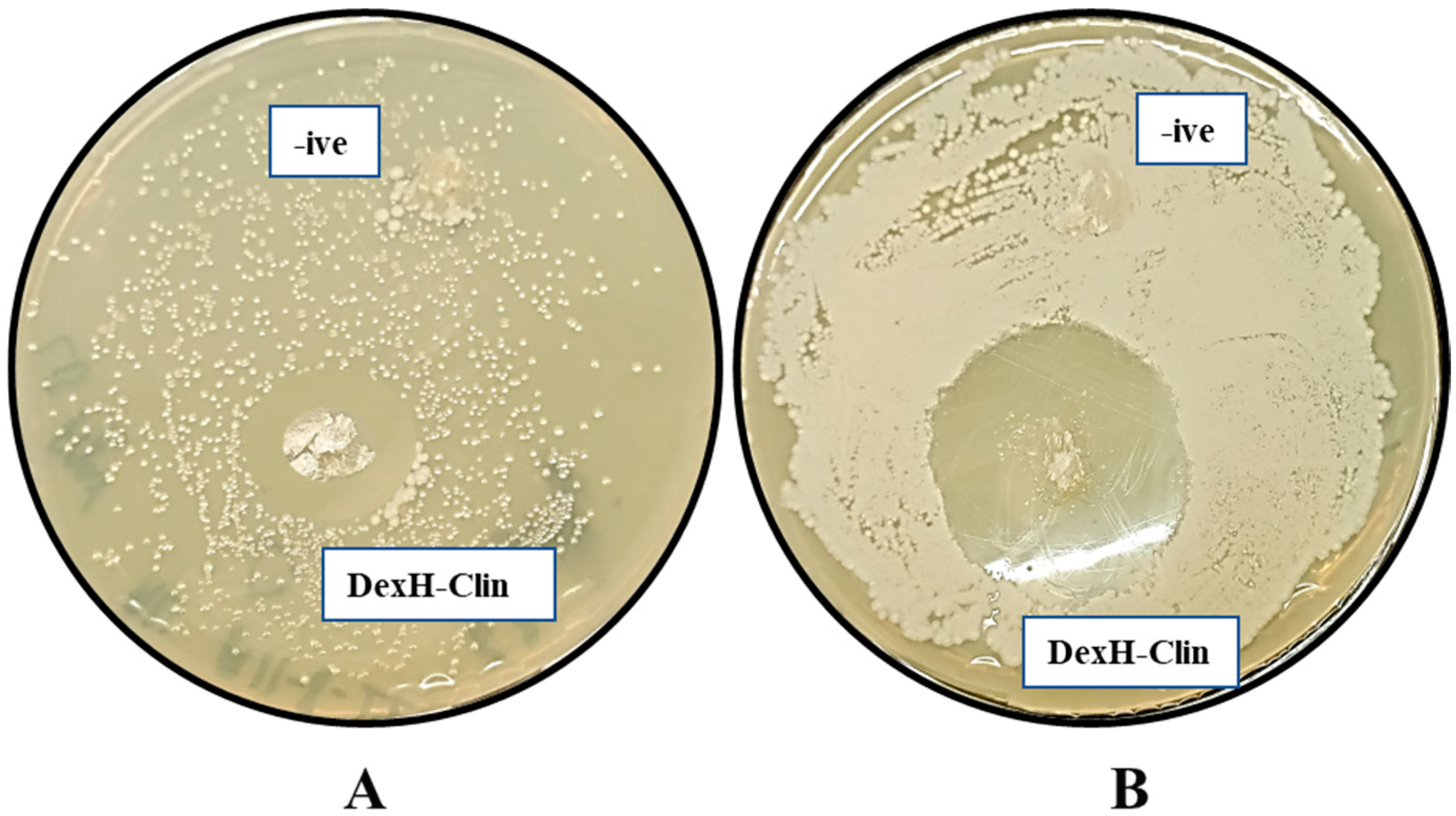

2.11. Antibacterial Assays of Clindamycin-Loaded Dextran Hydrogel (DexH-Clin)

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Microorganism and Dextran Production for This Study

4.2. Formulation of Dextran Hydrogel (DexH)

4.3. Effect of Crosslinker Concentration on the Synthesis of Dextran Hydrogel

4.4. Determination of Water Absorbency and Swelling Kinetics of Dextran Hydrogels

4.5. Effect of pH and Temperature on the Swelling of the Dextran Hydrogel

4.6. Analysis of Water Retention Capacity of Dextran Hydrogel

4.7. Estimation of Stability of Hydrogel

4.8. Morphological Characterization of Dextran Hydrogels Using Scanning Electron Microscopy

4.9. Drug Delivery Studies

4.9.1. Drug Loading Experiment

4.9.2. In Vitro Drug Release Studies

4.10. FTIR Analysis of Drug-Loaded Hydrogel

4.11. Antibacterial Assay

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tabernero, A.; Cardea, S. Microbial Exopolysaccharides as Drug Carriers. Polymers 2020, 12, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarquero, D.; Renes, E.; Fresno, J.M.; Tornadijo, M.E. Study of exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria and their industrial applications: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z. Polysaccharides-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörter, D.; Dressman, J. Influence of physicochemical properties on dissolution of drugs in the gastrointestinal tract. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Introducing the concept of prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, I.M. Advances in polysaccharide-based oral colon-targeted delivery systems: The journey so far and the road ahead. Cureus 2023, 15, e33636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovgaard, L.; Brøndsted, H. Dextran hydrogels for colon-specific drug delivery. J. Control. Release 1995, 36, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farasati Far, B.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Safaei, M.; Zarei, K.; Moradi, M.; Yazdani Nezhad, H. A review on biomedical application of polysaccharide-based hydrogels with a focus on drug delivery systems. Polymers 2022, 14, 5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.; Fernández, A.; Pérez, E.; Benito, M.; Teijón, J.; Blanco, M. Polysaccharide-based nanoparticles for controlled release formulations. Deliv. Nanopart. 2012, 16, 185–222. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Nadzir, M.; Nurhayati, R.W.; Idris, F.N.; Nguyen, M.H. Biomedical applications of bacterial exopolysaccharides: A review. Polymers 2021, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, Y.R.; Khosroushahi, A.Y.; Gargari, B.P. A comprehensive review of anticancer, immunomodulatory and health beneficial effects of the lactic acid bacteria exopolysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 217, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, H.; Guo, B.; Dong, R.; Qiu, Y.; Ma, P.X. Antibacterial anti-oxidant electroactive injectable hydrogel as self-healing wound dressing with hemostasis and adhesiveness for cutaneous wound healing. Biomaterials 2017, 122, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyanhongo, G.S.; Sygmund, C.; Ludwig, R.; Prasetyo, E.N.; Guebitz, G.M. An antioxidant regenerating system for continuous quenching of free radicals in chronic wounds. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 83, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, J.; Cao, L.; Jiao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Y. Antifouling antioxidant zwitterionic dextran hydrogels as wound dressing materials with excellent healing activities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7060–7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurden, A.T. The biology of the platelet with special reference to inflammation, wound healing and immunity. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2018, 23, 726–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Ye, B.; Wang, L. Antibiotics in soil and water in China–a systematic review and source analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, T.; Hasköylü, M.E.; Eroğlu, M.S.; Hemberger, J.; Öner, E.T. Levan-based hydrogels for controlled release of Amphotericin B for dermal local antifungal therapy of Candidiasis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 145, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Quan, Y.; Lai, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X.; Dai, T.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Y. A smart aminoglycoside hydrogel with tunable gel degradation, on-demand drug release, and high antibacterial activity. J. Control. Release 2017, 247, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dong, K.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. A β-Lactamase-Imprinted Responsive Hydrogel for the Treatment of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 8181–8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, C.; Wang, J.; Tavakoli, J.; Tang, Y. Novel bacterial cellulose-poly (acrylic acid) hybrid hydrogels with controllable antimicrobial ability as dressings for chronic wounds. Polymers 2018, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, G.; Lei, M.; Lei, J.; Li, D.; Zheng, H. A pH-sensitive oxidized-dextran based double drug-loaded hydrogel with high antibacterial properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, I.; Bin Tawseen, H.; Irfan, M.; Ahmad, W.; Hassan, M.; Sattar, F.; Awan, F.R.; Khaliq, S.; Akhtar, N.; Akhtar, K. Dietary Supplementation of Microbial Dextran and Inulin Exerts Hypocholesterolemic Effects and Modulates Gut Microbiota in BALB/c Mice Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, I.; Khaliq, S.; Akhtar, N.; Saleem, M.; Akhtar, K.; Ghauri, K.; Anwar, M.A. Genome analysis of novel Apilactobacillus sp. isolate from butterfly (Pieris canidia) gut reveals occurrence of unique glucanogenic traits and probiotic potential. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 76, ovac024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, E.C.; Gascon, J.; Anzelmo, G.; Barbosa, A.M.; da Cunha, M.A.A.; Dekker, R.F. Free-radical scavenging properties and antioxidant activities of botryosphaeran and some other β-D-glucans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.; Morgado, P.; Miguel, S.; Coutinho, P.; Correia, I. Dextran-based hydrogel containing chitosan microparticles loaded with growth factors to be used in wound healing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 2958–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosso, J.Q.; Armillei, M.K.; Lomakin, I.B.; Grada, A.; Bunick, C.G. Clindamycin: A comprehensive status report with emphasis on use in dermatology. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spížek, J.; Řezanka, T. Lincosamides: Chemical structure, biosynthesis, mechanism of action, resistance, and applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 133, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luanda, A.; Badalamoole, V. Past, present and future of biomedical applications of dextran-based hydrogels: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 228, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, A.R.; Pinteala, M.; Simionescu, N. Dextran formulations as effective delivery systems of therapeutic agents. Molecules 2023, 28, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.-Q.; Yi, J.-Z.; Zhang, L.-M. A facile approach to incorporate silver nanoparticles into dextran-based hydrogels for antibacterial and catalytical application. J. Macromol. Sci. Pure Appl. Chem. 2009, 46, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Pan, W.; Tong, X.; Zeng, Q.; Su, T.; Qi, X.; Shen, J. Polydopamine-incorporated dextran hydrogel drug carrier with tailorable structure for wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.; Choudhury, A.R. Synthesis and rheological characterization of a novel shear thinning levan gellan hydrogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Oner, E.T.; Eroglu, M.S. Novel levan and pNIPA temperature sensitive hydrogels for 5-ASA controlled release. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 165, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gull, N.; Khan, S.M.; Butt, M.T.Z.; Khalid, S.; Shafiq, M.; Islam, A.; Asim, S.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, R.U. In vitro study of chitosan-based multi-responsive hydrogels as drug release vehicles: A preclinical study. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 31078–31091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Saha, N.; Saha, P. Influence of temperature, pH and simulated biological solutions on swelling and structural properties of biomineralized (CaCO3) PVP–CMC hydrogel. Prog. Biomater. 2015, 4, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afinjuomo, F.; Barclay, T.G.; Song, Y.; Parikh, A.; Petrovsky, N.; Garg, S. Synthesis and characterization of a novel inulin hydrogel crosslinked with pyromellitic dianhydride. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 134, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Yue, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Yue, Q.; Meng, F. Design and fabrication of a triple-responsive chitosan-based hydrogel with excellent mechanical properties for controlled drug delivery. J. Polym. Res. 2018, 25, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, H.; Westerweel, J. Temperature-Sensitive Hydrogels. In Encyclopedia of Microfluidics and Nanofluidics; Li, D., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 2006–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.I.; Hwang, Y.; Sahu, A.; Min, K.; Sung, D.; Tae, G.; Chang, J.H. An injectable and physical levan-based hydrogel as a dermal filler for soft tissue augmentation. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 2627–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwat, F.; Qader, S.A.U.; Aman, A.; Ahmed, N. Production & characterization of a unique dextran from an indigenous Leuconostoc mesenteroides CMG713. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2008, 4, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, D.; Zhu, X.; Nie, J.; Ma, G. Electrospun and photocrosslinked gelatin/dextran–maleic anhydride composite fibers for tissue engineering. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 113, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhu, B.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Ren, N.; Tang, J.; Ma, X.; Su, Y.; Zhu, X. Micro-/nanofibers prepared via co-assembly of paclitaxel and dextran. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, N.; Cao, J.; Lee, J.; Hlaing, S.P.; Oshi, M.A.; Naeem, M.; Ki, M.-H.; Lee, B.L.; Jung, Y.; Yoo, J.-W. Bacteria-targeted clindamycin loaded polymeric nanoparticles: Effect of surface charge on nanoparticle adhesion to MRSA, antibacterial activity, and wound healing. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.O.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Jin, S.G.; Chang, S.W.; Li, D.X.; Hwang, M.-R.; Woo, J.S.; Kim, J.-A. Development of clindamycin-loaded wound dressing with polyvinyl alcohol and sodium alginate. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 2277–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, K.-Y.; Chung, R.-J.; Chang, P.-P.; Tsai, T.-H. Identification of Hydroxyl and Polysiloxane Compounds via Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy with Targeted Noise Analysis. Polymers 2025, 17, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purama, R.K.; Goyal, M.; Sharma, P.K.; Panwar, B. Production of dextran by Leuconostoc mesenteroides (MTCC 5142) utilizing sugarcane molasses as a carbon source. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 76, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Lin, Q.; Gao, Y.; Ye, L.; Xing, Y.; Xi, T. Characterization and antitumor activity of polysaccharide from Strongylocentrotus nudus eggs. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 67, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.Z.; Siddiqui, K.; Arman, M.; Ahmed, N. Characterization of high molecular weight dextran produced by Weissella cibaria CMGDEX3. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avşar, A.; Gökbulut, Y.; Ay, B.; Serin, S. A novel catalyst system for the synthesis of N, N′-Methylenebisacrylamide from acrylamide. Des. Monomers Polym. 2017, 20, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchian, I.; Goriuc, A.; Martu, M.A.; Covasa, M. Clindamycin as an alternative option in optimizing periodontal therapy. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, M.M.; Elakkad, Y.E.; Elwakeel, A.A.; Allam, R.M.; Mousa, M.R. Formulation and characterization of propolis and tea tree oil nanoemulsion loaded with clindamycin hydrochloride for wound healing: In-vitro and in-vivo wound healing assessment. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biver, S.; Steels, S.; Portetelle, D.; Vandenbol, M. Bacillus subtilis as a tool for screening soil metagenomic libraries for antimicrobial activities. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.; Khayi, S.; Berrada, J.; Mouahid, M.; Ameur, N.; El-Adawy, H.; Fellahi, S. Salmonella enterica serovar Gallinarum biovars Pullorum and Gallinarum in poultry: Review of pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance, diagnosis and control in the genomic era. Antibiotics 2023, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, X.; He, S.; Wen, J.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of pectin-chitosan hydrogels based on bioadhesive-design micelle to prompt bacterial infection wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ran, F.; Li, C.; Hao, Z.; He, H.; Dai, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, W. A lignin silver nanoparticles/polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate hybrid hydrogel with potent mechanical properties and antibacterial activity. Gels 2024, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenea, G.N.; Yépez, L. Bioactive compounds of lactic acid bacteria. Case study: Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-producing lactobacilli isolated from native ecological niches of Ecuador. In Probiotics and Prebiotics in Human Nutrition and Health; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- De Man, J.; Rogosa, D.; Sharpe, M.E. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1960, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, Y.; Azabou, S.; Casillo, A.; Gharsallah, H.; Jemil, N.; Lanzetta, R.; Attia, H.; Corsaro, M.M. Isolation and structural characterization of levan produced by probiotic Bacillus tequilensis-GM from Tunisian fermented goat milk. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo Toledo, L.E.; Gómez Riera, R.; Banguela Castillo, A.; Soto Romero, M.; Arrieta Sosa, J.G.; Hernández García, L. Catalytical properties of N-glycosylated Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus levansucrase produced in yeast. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2004, 7, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.A.; Kralj, S.; van der Maarel, M.J.; Dijkhuizen, L. The probiotic Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533 produces high-molecular-mass inulin from sucrose by using an inulosucrase enzyme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 3426–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assigned Vibration | Rationale/Typical Source |

|---|---|---|

| ~3300 | Broad O–H stretching (hydrogen-bonded hydroxyls; water/–OH of polysaccharide) | Typical for polysaccharides and hydrogels (O–H stretch). |

| 2920–2850 | C–H asymmetric/symmetric stretching (aliphatic CH2/CH3) | Common in sugars and crosslinkers. |

| ~1730 | C=O stretching (ester/carbonyl) | Present if crosslinker introduces ester groups or solvent residues. |

| 1650–1600 | H–O–H bending/amide I (if proteins present)/C=C conjugated modes | Interpret in context of sample composition. |

| 1575–1500 | Asymmetric COO− or aromatic ring modes (depends on crosslinker) | Check crosslinker chemistry. |

| 1425–1375 | CH2 bending/CH3 deformation | Typical skeletal vibrations. |

| 1260–1150 | C–O–C and C–O stretching (glycosidic linkages) | Characteristic of polysaccharide backbone and ethers. |

| 1120–1000 | Strong C–O stretching/ring vibrations (saccharide fingerprint) | Key carbohydrate region; used to confirm polysaccharide skeleton. |

| 900–700 | Anomeric C–H or glycosidic-related bands; ring deformation | Useful to indicate glycosidic linkages or substitution pattern. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jawad, I.; Rehman, A.; Hamdan, M.; Akhtar, K.; Khaliq, S.; Anwar, M.A.; Munawar, N. Development and Characterization of Clindamycin-Loaded Dextran Hydrogel for Controlled Drug Release and Pathogen Inhibition. Gels 2026, 12, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010082

Jawad I, Rehman A, Hamdan M, Akhtar K, Khaliq S, Anwar MA, Munawar N. Development and Characterization of Clindamycin-Loaded Dextran Hydrogel for Controlled Drug Release and Pathogen Inhibition. Gels. 2026; 12(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleJawad, Iqra, Asma Rehman, Mariam Hamdan, Kalsoom Akhtar, Shazia Khaliq, Munir Ahmad Anwar, and Nayla Munawar. 2026. "Development and Characterization of Clindamycin-Loaded Dextran Hydrogel for Controlled Drug Release and Pathogen Inhibition" Gels 12, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010082

APA StyleJawad, I., Rehman, A., Hamdan, M., Akhtar, K., Khaliq, S., Anwar, M. A., & Munawar, N. (2026). Development and Characterization of Clindamycin-Loaded Dextran Hydrogel for Controlled Drug Release and Pathogen Inhibition. Gels, 12(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010082