Injectable Scaffolds for Adipose Tissue Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Adipose Tissue Engineering

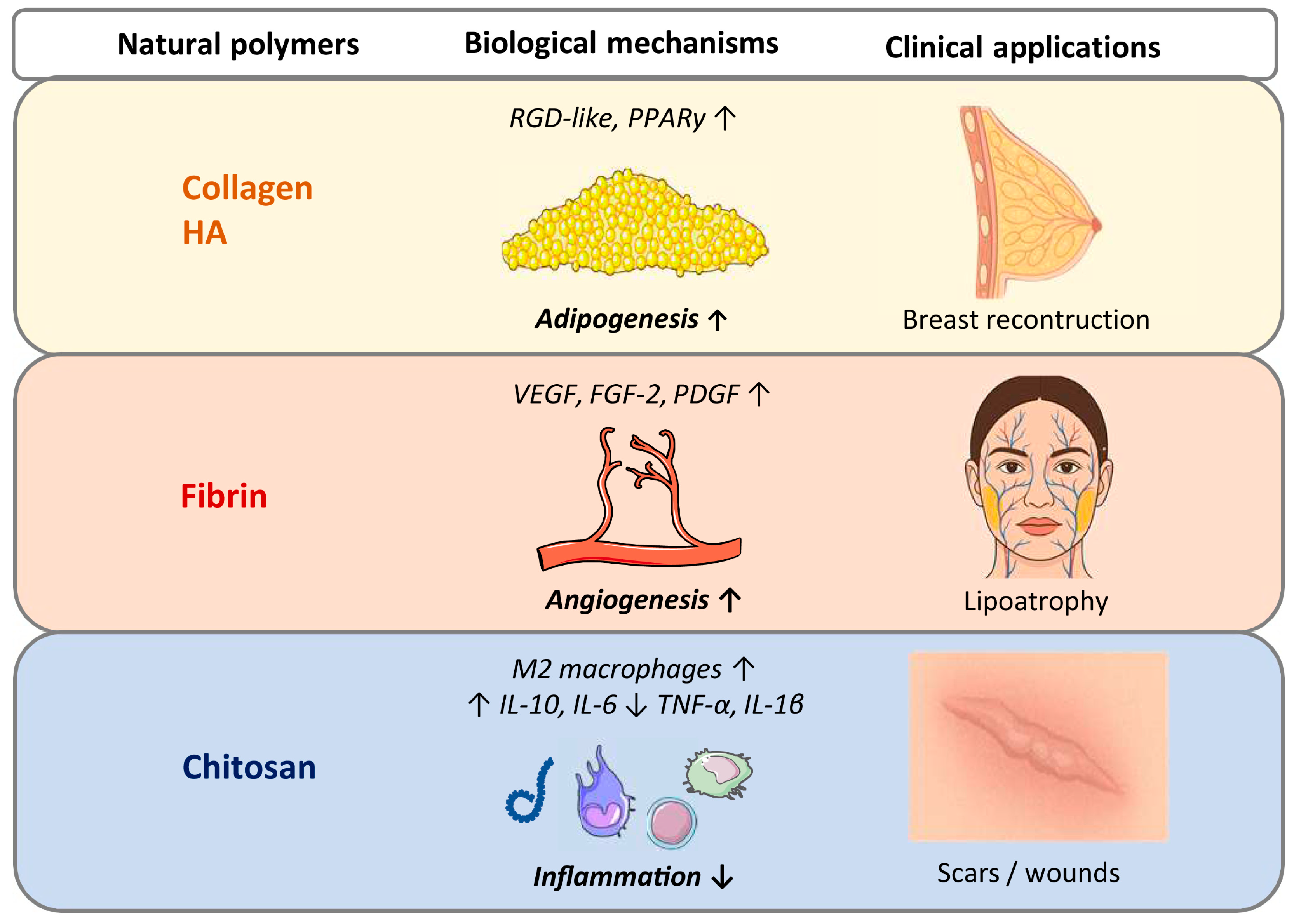

2.1. Natural Injectable Scaffolds

2.2. Synthetic Injectable Scaffolds

2.3. Adipose ECM-Derived Injectable Scaffolds

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acharya, P.; Mohammed, C.; Desai, A.; Rojas Gomez, M.C.; Sunil, G.; Duran, S.P.X.; Kocaekiz, S.; Thottakurichi, A.A.; Munoz, I.J.G.; Chavez-Alvarez, L.A.; et al. Maximizing the Longevity and Volume Retention of Fat Grafts: Advances in Clinical Practice. Cureus 2025, 17, e8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, T.; Brandão, I.; Negrão, R.; Martins, M.J.; Monteiro, R. Autologous fat grafting: Harvesting techniques. Ann. Med. Surg. 2018, 36, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wederfoort, J.L.M.; Hebels, S.A.; Heuts, E.M.; van der Hulst, R.R.W.J.; Piatkowski, A.A. Donor site complications and satisfaction in autologous fat grafting for breast reconstruction: A systematic review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2022, 75, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, B.; Guerrero, D.; De LaCruz, C.; Kokai, L. Fat grafting in autologous breast reconstruction: Applications, outcomes, safety, and complications. Plast. Aesthet. Res. 2023, 10, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Eto, H.; Kato, H.; Suga, H.; Aoi, N.; Doi, K.; Kuno, S.; Yoshimura, K. The fate of adipocytes after nonvascularized fat grafting: Evidence of early death and replacement of adipocytes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, L.L. Mechanisms of Fat Graft Survival. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 77, S84–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limido, E.; Weinzierl, A.; Harder, Y.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Fatter Is Better: Boosting the Vascularization of Adipose Tissue Grafts. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2020, 29, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ørholt, M.; Weltz, T.K.; Hemmingsen, M.N.; Larsen, A.; Bak, E.E.F.; Norlin, C.B.; Hart, L.; Elberg, J.J.; Vester-Glowinski, P.V.; Herly, M. Long-Term Volume Retention of Breast Augmentation with Fat Grafting Depends on Weight Changes: A 3-Year Prospective Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025, 155, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, J.A.M.; Tuin, A.J.; Loonen, T.G.J.; Dijkstra, P.U.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Schepers, R.H.; Jansma, J. Volume and patient satisfaction, 5 years of follow up after facial fat grafting. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2025, 102, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi, F.; Limido, E.; Weinzierl, A.; Harder, Y.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Preconditioning Strategies for Improving the Outcome of Fat Grafting. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2025, 31, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallah, J.C.; Wen, C.; Waldron, O.; Jikaria, N.R.; Asgardoon, M.H.; Schlidt, K.; Goldenberg, D.; Horchler, S.; Landmesser, M.E.; Park, J.H.; et al. Current Modalities in Soft-Tissue Reconstruction and Vascularized Adipose Engineering. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Paul, A.; Shakesheff, K.M. Injectable scaffolds for tissue regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. 2004, 14, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.A.; Christman, K.L. Injectable biomaterials for adipose tissue engineering. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 7, 024104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, H.; Durkut, S.; Koc-Demir, A.; Elçin, A.E.; Elçin, Y.M. Clinical Applications of Injectable Biomaterials. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1077, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katari, R.S.; Peloso, A.; Orlando, G. Tissue engineering. Adv. Surg. 2014, 48, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Halloran, N.A.; Dolan, E.B.; Kerin, M.J.; Lowery, A.J.; Duffy, G.P. Hydrogels in adipose tissue engineering—Potential application in post-mastectomy breast regeneration. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 12, 2234–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.S.; Choi, Y.C.; Kim, J.D.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Kwon, I.C.; Cho, Y.W. Adipose tissue: A valuable resource of biomaterials for soft tissue engineering. Macromol. Res. 2014, 22, 932–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.A.; Choi, Y.S.; Engler, A.J.; Christman, K.L. Stimulation of adipogenesis of adult adipose-derived stem cells using substrates that mimic the stiffness of adipose tissue. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8581–8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, L.; Davis, M.J.; Winocour, S.J. The Science of Fat Grafting. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2020, 34, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Rubin, J.P.; Marra, K.G. Injectable in situ forming biodegradable chitosan–hyaluronic acid–based hydrogels for adipose tissue regeneration. Organogenesis 2010, 6, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Naranjo, J.D.; Londono, R.; Badylak, S.F. Biologic Scaffolds. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a025676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.A.; Ibrahim, D.O.; Hu, D.; Christman, K.L. Injectable hydrogel scaffold from decellularized human lipoaspirate. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriel, S.; Labay, E.; Francis-Sedlak, M.; Moya, M.L.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Ervin, N.; Cankova, Z.; Brey, E.M. Extraction and assembly of tissue-derived gels for cell culture and tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods. 2009, 15, 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hedén, P.; Sellman, G.; von Wachenfeldt, M.; Olenius, M.; Fagrell, D. Body Shaping and Volume Restoration: The Role of Hyaluronic Acid. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2020, 44, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faivre, J.; Pigweh, A.I.; Iehl, J.; Maffert, P.; Goekjian, P.; Bourdon, F. Crosslinking hyaluronic acid soft-tissue fillers: Current status and perspectives from an industrial point of view. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 2021, 18, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Torio-Padron, N.; Baerlecken, N.; Momeni, A.; Stark, G.B.; Borges, J. Engineering of adipose tissue by injection of human preadipocytes in fibrin. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2007, 31, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Lin, Y.N.; Lee, S.S.; Chai, C.Y.; Chang, H.W.; Lin, T.M.; Lai, C.S.; Lin, S.D. New adipose tissue formation by human adipose-derived stem cells with hyaluronic acid gel in immunodeficient mice. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 12, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Çekiç, D.; Yılmaz, Ş.N.; Bölgen, N.; Ünal, S.; Duce, M.N.; Bayrak, G.; Demir, D.; Türkegün, M.; Sarı, A.; Demir, Y.; et al. Impact of injectable chitosan cryogel microsphere scaffolds on differentiation and proliferation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells into fat cells. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 36, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo-Alcazar, R.; Bendix, S.; Groth, T.; Gallego Ferrer, G. Research Progress in Enzymatically Cross-Linked Hydrogels as Injectable Systems for Bioprinting and Tissue Engineering. Gels 2023, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goder Orbach, D.; Roitman, I.; Coster Kimhi, G.; Zilberman, M. Formulation–Property Effects in Novel Injectable and Resilient Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels for Soft Tissue Regeneration. Polymers 2024, 16, 2879. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cid, P.; Alonso-González, M.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Benhnia, M.R.; Ruiz-Mateos, E.; Ostos, F.J.; Romero, A.; Perez-Puyana, V.M. Effect of different crosslinking agents on hybrid chitosan/collagen hydrogels for potential tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 129858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, F.; Sowa, Y.; Irie, S.; Higuchi, Y.; Kitano, S.; Mazda, O.; Matsusaki, M. Injectable Prevascularized Mature Adipose Tissues (iPAT) to Achieve Long-Term Survival in Soft Tissue Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2201440. [Google Scholar]

- Challapalli, R.S.; O’Dwyer, J.; McInerney, N.; Kerin, M.J.; Duffy, G.P.; Dolan, E.B.; Roisin, M.D.; Lowery, A.J. Evaluation of adipose-derived stromal cell infused modified-hyaluronic acid scaffolds for post cancer breast reconstruction. bioRxiv 2025, 2025-04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Zhang, R.; Lin, F.; Luan, J. Injectable cell/hydrogel microspheres induce the formation of fat lobule-like microtissues and vascularized adipose tissue regeneration. Biofabrication 2012, 4, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Sun, J.; Tan, H.; Yuan, G.; Li, J.; Jia, Y.; Xiong, D.; Chen, G.; Lai, J.; Ling, Z.; et al. Covalently polysaccharide-based alginate/chitosan hydrogel embedded alginate microspheres for BSA encapsulation and soft tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 127, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidenko, N.; Campbell, J.J.; Thian, E.S.; Watson, C.J.; Cameron, R.E. Collagen–hyaluronic acid scaffolds for adipose tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3957–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puls, T.J.; Fisher, C.S.; Cox, A.; Plantenga, J.M.; McBride, E.L.; Anderson, J.L.; Goergen, C.J.; Bible, M.; Moller, T.; Voytik-Harbin, S.L. Regenerative tissue filler for breast conserving surgery and other soft tissue restoration and reconstruction needs. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blache, U.; Ehrbar, M. Inspired by Nature: Hydrogels as Versatile Tools for Vascular Engineering. Adv. Wound Care 2018, 7, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, K.; Dietl, S.; Ludwig, N.; Berberich, O.; Hoefner, C.; Storck, K.; Blunk, T.; Bauer-Kreisel, P. Engineering vascularized adipose tissue using the stromal-vascular fraction and fibrin hydrogels. Tissue Eng. Part A 2015, 21, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Buschle-Diller, G.; Misra, R.D.K. Chitosan-based injectable hydrogels for biomedical applications. Mater. Technol. 2015, 30, B198–B205. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari Keshel, S.; Rostampour, M.; Khosropour, G.; Bandbon, B.A.; Baradaran-Rafii, A.; Biazar, E. Derivation of epithelial-like cells from eyelid fat-derived stem cells in thermosensitive hydrogel. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2016, 27, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Jin, Z.; Liu, X.; Ouyang, L.; Liao, Y. Chitosan@ Puerarin hydrogel for accelerated wound healing in diabetic subjects by miR-29ab1 mediated inflammatory axis suppression. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 19, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ali, A.; Mulinari Dos Santos, G.; Franciscon, J.P.S.; de Molon, R.S.; Goh, C.; Ervolino, E.; Theodoro, L.H.; Shrestha, A. A Chitosan-based Hydrogel to Modulate Immune Cells and Promote Periodontitis Healing in the High-Fat Diet-Induced Periodontitis Rat Model. Acta Biomater. 2025, 200, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.N.; Gobin, A.S.; West, J.L.; Patrick, C.W., Jr. Poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel system supports preadipocyte viability, adhesion, and proliferation. Tissue Eng. 2005, 11, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, F.P.; Seitz, A.K.; Tessmar, J.K.; Blunk, T.; Göpferich, A.M. Enzymatically degradable poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels for adipose tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3957–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Fang, W.; Wang, F. Injectable fillers: Current status, physicochemical properties, function mechanism, and perspectives. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 23841–23858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemperle, G.; Morhenn, V.; Charrier, U. Human histology and persistence of various injectable filler substances for soft tissue augmentation. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2003, 27, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dethe, M.R.; A, P.; Ahmed, H.; Agrawal, M.; Roy, U.; Alexander, A. PCL–PEG copolymer-based injectable thermosensitive hydrogels. J. Control. Release 2022, 343, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuco, R.; Evangelista, C.; Gobbato, D.O.; de Almeida, L.M. Clinical and histological comparative outcomes after injections of poly-L-lactic acid and calcium hydroxyapatite in arms: A split-side study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 6727–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hong, H.J.; Ahn, S.; Kim, D.; Kang, S.H.; Cho, K.; Koh, W.G. One-Pot Synthesis of Double-Network PEG/Collagen Hydrogel for Enhanced Adipogenic Differentiation and Retrieval of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Polymers 2023, 15, 1777. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, D.; Fischer, K.S.; Chen, K.; Greco, A.H.; Martin, R.A.; Sivaraj, D.; Trotsyuk, A.A.; Mao, H.Q.; Reddy, S.K.; Kneser, U.; et al. Enrichment of Nanofiber Hydrogel Composite with Fractionated Fat Promotes Regenerative Macrophage Polarization and Vascularization for Soft-Tissue Engineering. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 433e–444e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Poche, J.N.; Liu, Y.; Scherr, T.; McCann, J.; Forghani, A.; Smoak, M.; Muir, M.; Berntsen, L.; Chen, C.; et al. Hybrid Synthetic–Biological Hydrogel System for Adipose Tissue Regeneration. Macromol. Biosci. 2018, 18, e1800122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; McCann, J.; Ravnic, D.J.; Gimble, J.M.; Hayes, D.J. Hybrid adipose graft materials synthesized from chemically modified adipose extracellular matrix. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2022, 110, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, D.S.; Ha, H.J.; Jung, J.W.; Baek, S.W.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, J.C.; Hwang, E.; Han, D.K. Fat Graft with Allograft Adipose Matrix and Magnesium Hydroxide-Incorporated PLGA Microspheres for Effective Soft Tissue Reconstruction. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 19, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Beynet, D.P.; Gharavi, N.M. Overview of Deep Dermal Fillers. Facial Plast. Surg. 2019, 35, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Yang, W.; He, T.; Wu, J.; Zou, M.; Liu, X.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Lai, C.; Wang, J. Clinical applications of a novel poly-L-lactic acid microsphere and hyaluronic acid suspension for facial depression filling and rejuvenation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 3508–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zou, M.; Chen, W.; Qiao, G.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Diao, Y.; Cai, W. Enhancing Facial Projection: Efficacy and Safety of a Novel Filler Combining Cross-Linked Sodium Hyaluronate Gel With Poly-L-Lactic Acid-b-PEG Microspheres for T-Zone Augmentation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Liu, Y.; Hui, L. Preparation and characterization of acellular adipose tissue matrix using a combination of physical and chemical treatments. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, C.M.; Imbarlina, C.; Yates, C.C.; Marra, K.G. Current Therapeutic Strategies for Adipose Tissue Defects/Repair Using Engineered Biomaterials and Biomolecule Formulations. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldin, L.T.; Cramer, M.C.; Velankar, S.S.; White, L.J.; Badylak, S.F. Extracellular matrix hydrogels from decellularized tissues: Structure and function. Acta Biomater. 2017, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriel, S.; Huang, J.J.; Moya, M.L.; Francis, M.E.; Wang, R.; Chang, S.Y.; Cheng, M.H.; Brey, E.M. The role of adipose protein derived hydrogels in adipogenesis. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3712–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Lyu, T.J.; Fu, B.; Wang, Y.; Qu, Q.; Wang, F.; Guo, R.; Fan, J. Advances and challenges in decellularized adipose tissue–based composite hydrogels for adipose tissue regeneration: A review over the last fifteen years. Theranostics 2025, 15, 9508–9532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.J.; Gimble, J.M. Developing a clinical-grade human adipose decellularized biomaterial. Biomater. Biosyst. 2022, 7, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.; Nahas, Z.; Kimmerling, K.A.; Rosson, G.D.; Elisseeff, J.H. An injectable adipose matrix for soft-tissue reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.J.; Pereira, E.; Cotta, M.V.; Sinha, S.; Palmer, J.A.; Woods, A.A.; Morrison, W.A.; Abberton, K.M. Preparation of an adipogenic hydrogel from subcutaneous adipose tissue. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 5609–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, D.A.; Bajaj, V.; Christman, K.L. Award winner for outstanding research in the PhD category, 2014 Society for Biomaterials Annual Meeting and Exposition, Denver, Colorado, April 16–19, 2014: Decellularized adipose matrix hydrogels stimulate in vivo neovascularization and adipose formation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2014, 102, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Kokai, L.E.; Schilling, B.K.; Chnari, E.; Huang, Y.C.; Imming, E.A.; Karunamurthy, A.; Khouri, R.K.; D’Amico, R.A.; Coleman, S.R.; Marra, K.G.; et al. Injectable allograft adipose matrix supports adipogenic tissue remodeling in the nude mouse and human. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 143, 299e–309e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.E.; Wu, I.; Parrillo, A.J.; Wolf, M.T.; Maestas, D.R., Jr.; Graham, I.; Tam, A.J.; Payne, R.M.; Aston, J.; Cooney, C.M.; et al. An immunologically active, adipose-derived extracellular matrix biomaterial for soft tissue reconstruction: Concept to clinical trial. NPJ Regen. Med. 2022, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, J.C.; Zhang, D.; Xiong, B.J.; Yang, J.Q.; Xie, H.Q.; Lv, Q. Hydrogel derived from decellularized porcine adipose tissue as a promising biomaterial for soft tissue augmentation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2017, 105, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.T.; Toutounji, S.; Amsden, B.G.; Flynn, L.E. Adipose-derived stromal cells mediate in vivo adipogenesis, angiogenesis and inflammation in decellularized adipose tissue bioscaffolds. Biomaterials 2015, 72, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lu, Q.; Cao, T.; Toh, W.S. Adipose tissue and extracellular matrix development by injectable decellularized adipose matrix loaded with basic fibroblast growth factor. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokai, L.E.; Sivak, W.N.; Schilling, B.K.; Karunamurthy, A.; Egro, F.M.; Schusterman, M.A.; Minteer, D.M.; Simon, P.; D’Amico, R.A.; Rubin, J.P. Clinical evaluation of an off-the-shelf allogeneic adipose matrix for soft tissue reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2020, 8, e2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M.H.; Kinney, B.M.; Kaminer, M.S.; Rohrich, R.J.; D’Amico, R.A. A multicenter, open-label, pilot study of allograft adipose matrix for the correction of atrophic temples. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1044–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

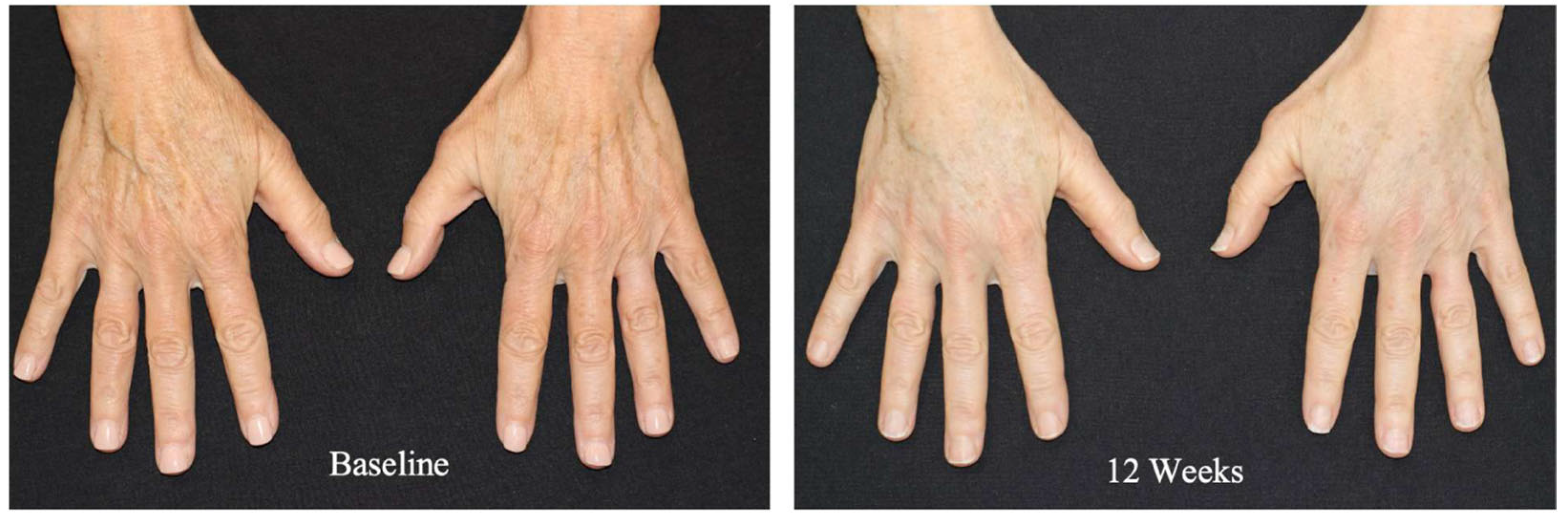

- Gold, M.; Biesman, B.; Cohen, J.; Day, D.; Goldberg, D.; Guénin, S.; Lain, T.; Schlesinger, T.; Shamban, A.; Chilukuri, S. Real-world clinical experience with an allograft adipose matrix for replacing volume loss in face, hands, and body. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin, T.B.; Vaishnav, K.V.; Watchman, M.; Subbian, V.; Larson, E.; Chnari, E.; Armstrong, D.G. Tissue augmentation with allograft adipose matrix for the diabetic foot in remission. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, C.J.; Gonzalez, D.I.; Gelles-Soto, D.; Mercado, A. Use of allograft fat for aesthetic and functional restoration of soft-tissue contour deformities. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 2023, rjac629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Injectable Scaffold | Bioactivity | Biocompatibility | Inflammatory and Fibrotic Reaction | Mechanical Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Synthetic | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| Adipose ECM-derived | +++ | +++ | + | + |

| Commercial Name (Company) | Composition | Approval |

|---|---|---|

| Algeness® (Advanced Aesthetic Technologies, Brookline, MA, USA) | Agarose gel | CE-marked |

| Bellafill® (Suneva Medical, San Diego, CA, USA) | Type I bovine collagen gel | FDA-approved |

| Belotero® (Merz Aesthetics, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) | HA gel | CE-marked and FDA-approved |

| Evolence® (ColBar LifeScience Ltd., Herzliya, Israel) | Type I porcine collagen | CE-marked and FDA-approved |

| GeneFill DX (BioScience GmbH, Radeberg, Germany) | HA gel | CE-marked |

| Lava® (BioScience GmbH, Radeberg, Germany) | Type I porcine collagen | CE-marked |

| Linerase® (Euroresearch, Milan, Italy) | Type I equine collagen | CE-marked |

| Juvéderm® (Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) | HA gel | CE-marked and FDA-approved |

| Restylane® (Galderma, Zug, Switzerland) | HA gel | CE-marked and FDA-approved |

| Revanesse® VersaTM (Prollenium, Toronto, ON, Canada) | HA gel | CE-marked and FDA-approved |

| Saypha® (Croma Pharma, Leobendorf, Austria) | HA gel | CE-marked |

| Sisderm® (Euroresearch, Milan, Italy) | Type I equine collagen | CE-marked |

| Stylage® (Vivacy, Archamps, France) | HA gel | CE-marked |

| Teosyal® (Teoxane, Geneva, Switzerland) | HA gel | CE-marked and FDA-approved |

| YVOIRE® (LG Chem, Seoul, South Korea) | HA gel | CE-marked |

| Zyderm® (Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) | Type I bovine collagen | FDA-approved |

| Tissue Source | Decellularization Reagent | Delipidization Reagent | Solubilization Reagent | In Vitro Property | In Vivo Property | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 1% SDS, or 2.5 mM sodium deoxycholate | 2.5 mM sodium deoxycholate with 500 U lipase and 500 U colipase | 1 mg/mL pepsin, 0.1 M HCl | ASC adhesion, viability and proliferation ↑ | Shape ↔ | [22] |

| Human | 3% peracetic acid, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 600 U/mL DNase, 10 mM MgCl2 | Triton X-100, extensive washing | 1 mg/mL pepsin, 0.1 M HCl | ASC adhesion, viability and adipogenic differentiation ↑ | Adipogenesis ↑ Inflammation ↔ Vascularization ↑ | [64] |

| Porcine | 2 U/mL dispase II, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM NEM, 8 mM EDTA | Extensive washing, centrifugation, 0.2 mm filtration | 1% pepsin, 0.5 M acetic acid | ASC infiltration, TNF-α, MCP-1 expression ↑ | Adipogenesis ↑ Vascularization ↑ | [65] |

| Human | 1% SDS, 0.01% Triton X-100 | 2.5 mM sodium deoxycholate with 500 U lipase and 500 U colipase | 1 mg/mL pepsin, 0.1 M HCl | ASC adhesion, viability and adipogenic differentiation ↑ | Not tested | [66] |

| Human | sodium deoxycholate, peracetic acid | 1-propanol | 1 mg/mL pepsin, 0.1 M HCl | ASC adhesion, infiltration and adipogenic differentiation ↑ | Adipogenesis ↑ Biocompatibility ↔ Vascularization ↑ Volume ↔ | [67] |

| Human | 3% peracetic acid, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA | Infinity TG Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) | 4 M guanidine HCl | ASC migration, adhesion and adipogenic differentiation ↑ | Adipogenesis ↑ Necrosis, cysts ↓ Pro-regenerative environment ↑ Volume ↔ | [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pruzzo, V.; Bonomi, F.; Limido, E.; Weinzierl, A.; Harder, Y.; Laschke, M.W. Injectable Scaffolds for Adipose Tissue Reconstruction. Gels 2026, 12, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010081

Pruzzo V, Bonomi F, Limido E, Weinzierl A, Harder Y, Laschke MW. Injectable Scaffolds for Adipose Tissue Reconstruction. Gels. 2026; 12(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010081

Chicago/Turabian StylePruzzo, Valeria, Francesca Bonomi, Ettore Limido, Andrea Weinzierl, Yves Harder, and Matthias W. Laschke. 2026. "Injectable Scaffolds for Adipose Tissue Reconstruction" Gels 12, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010081

APA StylePruzzo, V., Bonomi, F., Limido, E., Weinzierl, A., Harder, Y., & Laschke, M. W. (2026). Injectable Scaffolds for Adipose Tissue Reconstruction. Gels, 12(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010081