Carrier-Free Supramolecular Hydrogel Self-Assembled from Triterpenoid Saponins from Traditional Chinese Medicine: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

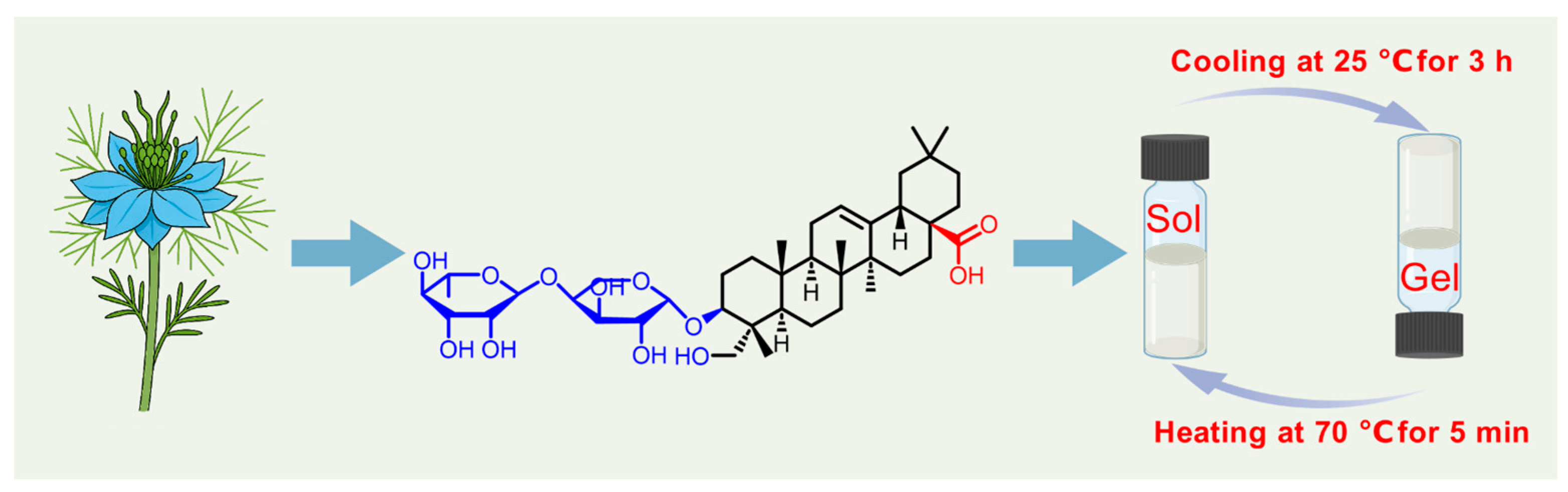

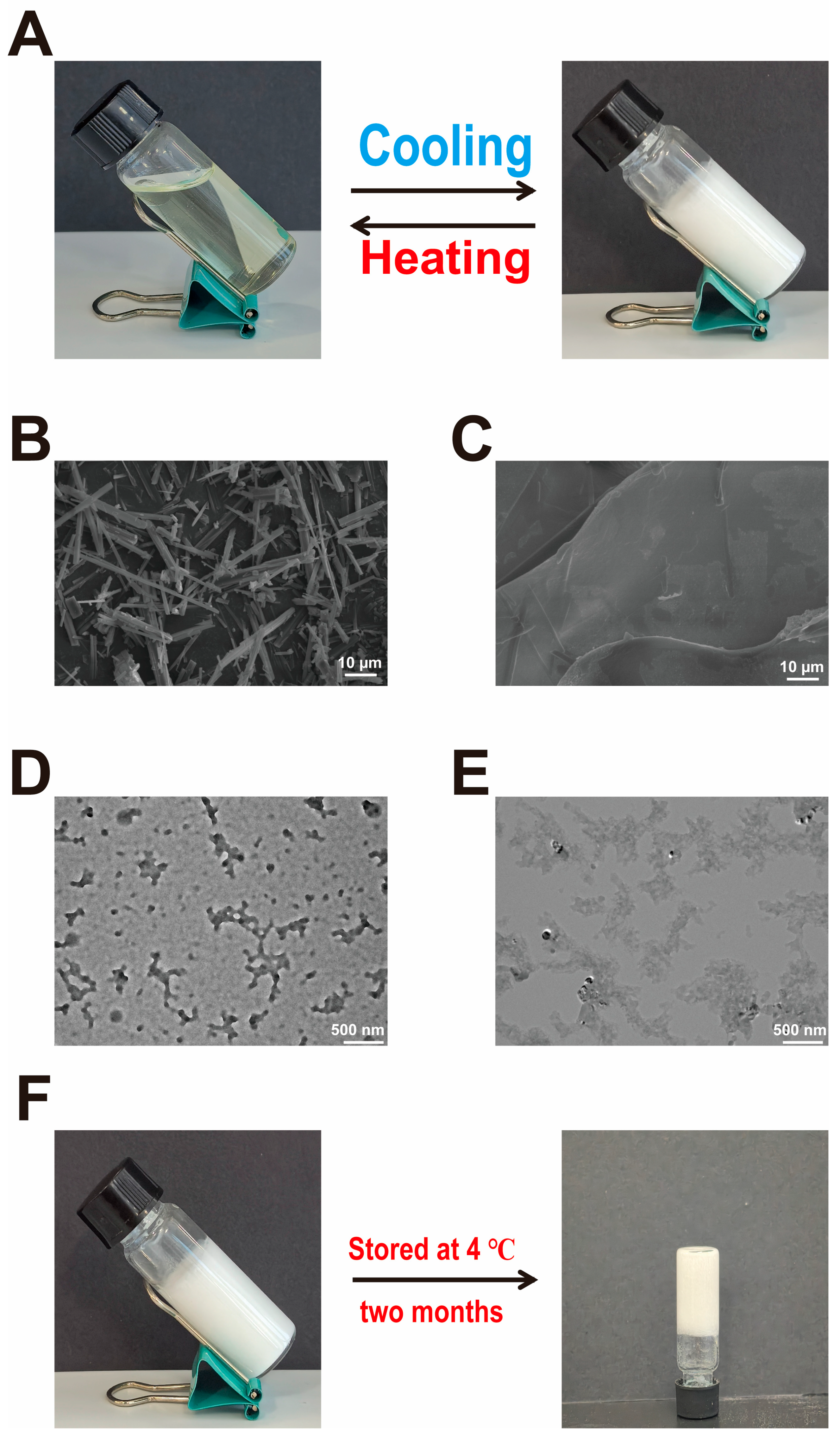

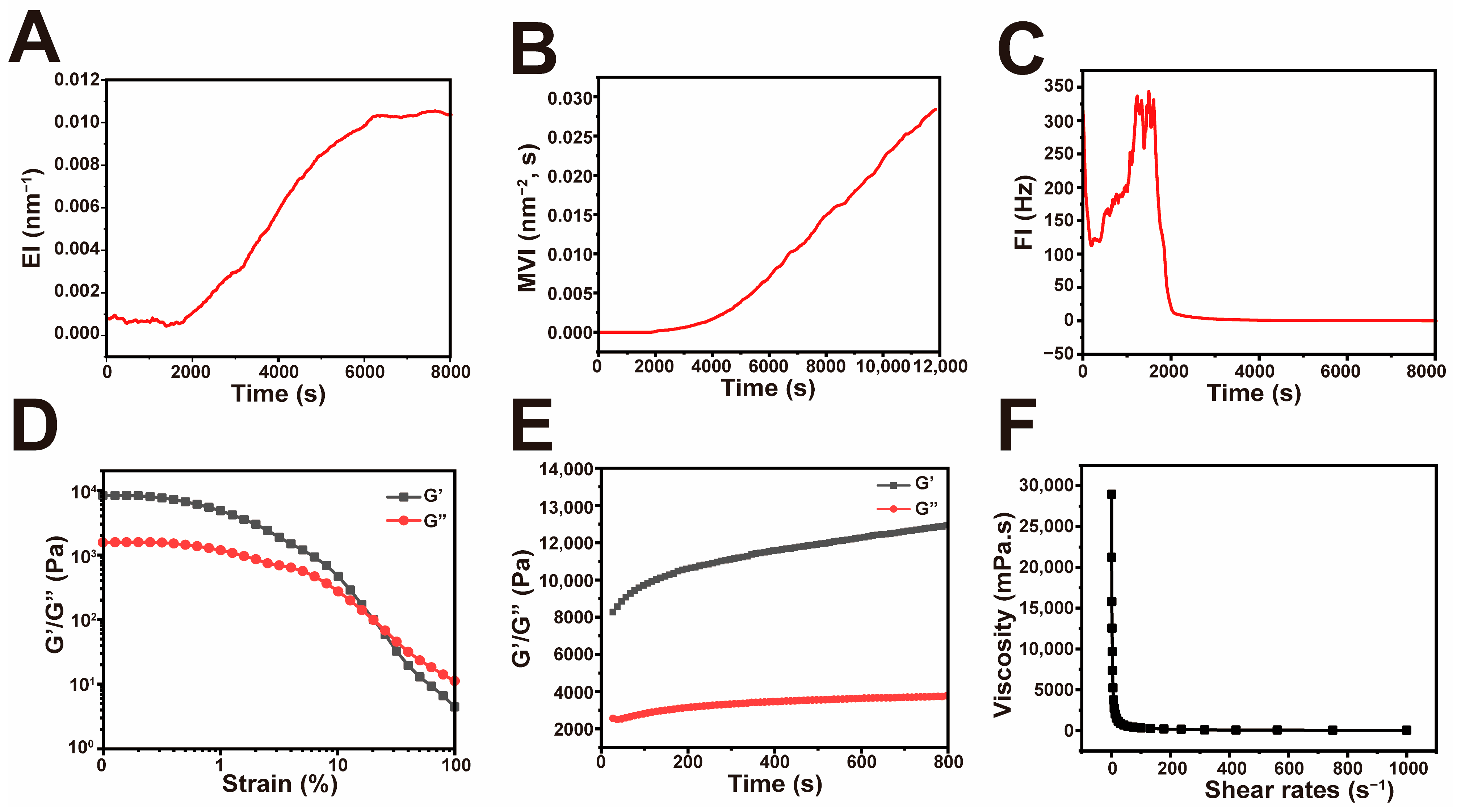

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of He-Gel

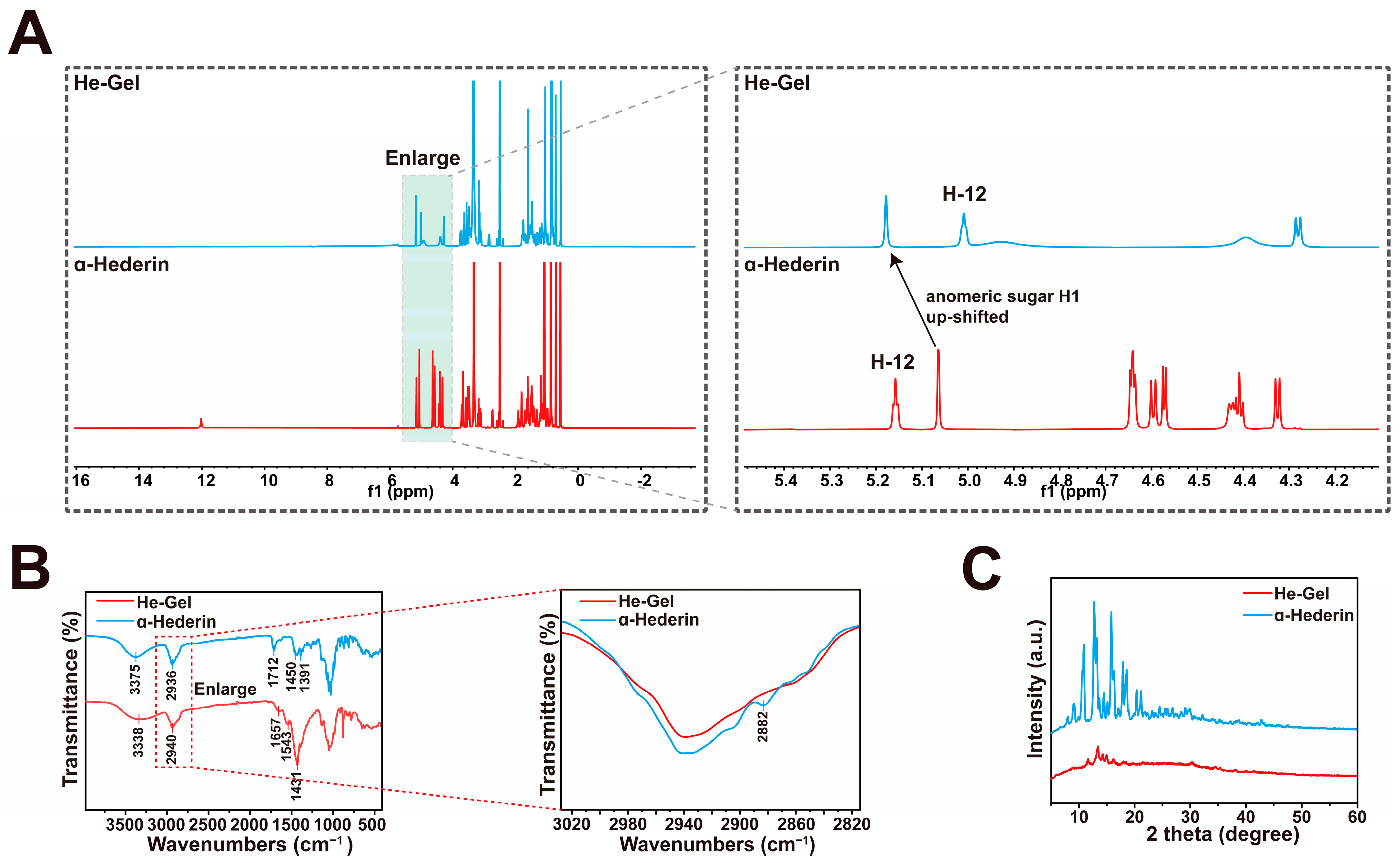

2.2. The Self-Assembly Mechanism of He-Gel

2.3. Density-Functional Theory (DFT) Calculation of He-Gel

2.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of He-Gel

2.5. Low Toxicity and Better Anti-Inflammatory Activity In Vitro of He-Gel

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents, Cell Line, and Materials

4.2. Preparation of the He-Gel

4.3. Morphological Characterization

4.4. Micro-Rheological Test

4.5. Rheological Test

4.6. 1H NMR Test

4.7. FT-IR Test

4.8. XRD Test

4.9. DFT Calculation

4.10. MD Stimulation of He-Gel

4.11. In Vitro Release Determination

4.12. RAW264.7 Cells Culture

4.13. Cell Viability Assay

4.14. Elisa Detecting of RAW264.7 Cells’ Supernatants

4.15. qPCR Determination

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Eapen, V.V.; Liang, Y.; Kournoutis, A.; Sherman, M.S.; Xu, Y.; Onorati, A.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Corey, K.E. WSTF nuclear autophagy regulates chronic but not acute inflammation. Nature 2025, 644, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pofi, R.; Caratti, G.; Ray, D.W.; Tomlinson, J.W. Treating the side effects of exogenous glucocorticoids; can we separate the good from the bad? Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 975–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryer, B.; Kimmey, M.B. Gastrointestinal side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am. J. Med. 1998, 105, 20S–30S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürst, R.; Zündorf, I. Plant-derived anti-inflammatory compounds: Hopes and disappointments regarding the translation of preclinical knowledge into clinical progress. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 146832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, T.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Jia, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L. The anti-inflammatory effects of saponins from natural herbs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 269, 108827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Ren, M.; Li, M.; Wang, M.; Geng, W.; Shang, Q. Molecular mechanism of α-Hederin in tumor progression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 116097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Fallahi, M.; Aslani, M.R. The protective effect of α-hederin, the active constituent of Nigella sativa, on tracheal responsiveness and lung inflammation in ovalbumin-sensitized guinea pigs. J. Physiol. Sci. 2015, 65, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulin-Traffort, J.; Favel, A.; Elias, R.; Regli, P. Study of the action of α-hederin on the ultrastructure of Candida albicans. [Untersuchungen zur Wirkung von α-Hederin auf die Ultrastruktur von Candida albicans]. Mycoses 1998, 41, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Zhao, G. α-Hederin regulates macrophage polarization to relieve sepsis-induced lung and liver injuries in mice. Open Med. 2023, 18, 20230695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.H.; Yen, F.L.; Lin, L.T.; Tsai, T.R.; Lin, C.C.; Cham, T.M. Preparation, physicochemical characterization, and antioxidant effects of quercetin nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 346, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, T.; Xu, J. Improving the anticancer activity of α-hederin by physically encapsulating it with targeted micelles assembled from amphiphilic block copolymers. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 35, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xu, X.-N.; Zhi-Min, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, F. Prediction and verification of targets for α-hederin/oxaliplatin dual-loaded rHDL modified liposomes: Reversing effector T-cells dysfunction and improving anti-COAD efficiency in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 662, 124512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Fan, R.; Wu, H.; Yao, H.; Yan, Y.; Liu, J.; Ran, L.; Sun, Z.; Yi, L.; Dang, L. Directed self-assembly of herbal small molecules into sustained release hydrogels for treating neural inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Peng, Q.; Li, W.; Chen, X.; Yan, Q.; Wu, X.; Wu, M.; Yuan, D.; Song, H.; Shi, J. Atomic Insights Into Self-Assembly of Zingibroside R1 and its Therapeutic Action Against Fungal Diseases. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2503283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Wu, P.; Feng, C.; Li, Q.; Xu, X.; Sun, Z.; Ma, G. Degradable carrier-free spray hydrogel based on self-assembly of natural small molecule for prevention of postoperative adhesion. Mater Today Bio 2023, 22, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Hou, Y.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Z.; Xu, X.; Yang, L.; Huo, X.; Ma, G. Directed co-assembly of binary natural small molecules into carrier-free sprayable gel with synergistic multifunctional activity for perishable fruits preservation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 152104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cheng, X.; Huang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Xiao, J.; Hu, J. Sprayable Antibacterial Hydrogels by Simply Mixing of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics and Cellulose Nanocrystals for the Treatment of Infected Wounds. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2270123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, T.; Sun, Z.; Xu, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Tian, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, N. Co-assembly of natural small molecules into a carrier-free hydrogel with enhanced synergism for pancreatic cancer theranostic amplification. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 32, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Gong, W.; Wang, X.; He, W.; Hou, Y.; Hu, J. Self-assembly of naturally small molecules into supramolecular fibrillar networks for wound healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chen, S.; Cao, N.; Zheng, W.; Li, D.; Sheng, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Wu, K. A novel 18 β-glycyrrhetinic acid derivative supramolecular self-assembly hydrogel with antibacterial activity. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 17254–17267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Pi, W.; Huang, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, H.; Wang, P. Natural Carrier-Free Binary Small Molecule Self-Assembled Hydrogel Synergize Antibacterial Effects and Promote Wound Healing by Inhibiting Virulence Factors and Alleviating the Inflammatory Response. Small 2023, 19, e2205528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Pi, W.; Xu, R.; Yao, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, J.; Li, G.; et al. Supramolecular Chiral Amplification Mediated by Tiny Structural Changes in Natural Binary Carrier-Free Hydrogels with Promotion Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus-Infected wound Healing by Inhibiting the Complement System. Small Struct. 2025, 6, 2400507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Yu, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Physical ionogels with only 2 wt% gelators as efficient quasi-solid-state electrolytes for lithium batteries. Matter 2024, 7, 1558–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biharee, A.; Singh, Y.; Kulkarni, S.; Jangid, K.; Kumar, V.; Jain, A.K.; Thareja, S. An amalgamated molecular dynamic and Gaussian based 3D-QSAR study for the design of 2, 4-thiazolidinediones as potential PTP1B inhibitors. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2024, 127, 108695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, H.; Müller-Plathe, F. Self-Assembly Pathways of Triblock Janus Particles into 3D Open Lattices. Small 2024, 20, 2306337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-B.; Luo, K.; Lee, H.; Lim, M.-C.; Yu, J.; Choi, S.-J.; Kim, K.-B.; Jeon, T.-J.; Kim, Y.-R. Alpha-Hederin nanopore for single nucleotide discrimination. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorent, J.; Lins, L.; Domenech, O.S.; Quetin-Leclercq, J.; Brasseur, R.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.-P. Domain formation and permeabilization induced by the saponin α-hederin and its aglycone hederagenin in a cholesterol-containing bilayer. Langmuir 2014, 30, 4556–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, C.; Gao, B.; Wang, W.; Ding, C.; He, B.; Zhu, X. Honeysuckle-Derived Carbon Dots With Robust Catalytic and Pharmacological Activities for Mitigating Lung Inflammation by Inhibition of Caspase11/GSDMD-Dependent Pyroptosis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2418683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Q.; Liu, M.; Ye, T.; Mo, D.; Wu, H.; Ma, G.; Zhou, X. Carrier-Free Supramolecular Hydrogel Self-Assembled from Triterpenoid Saponins from Traditional Chinese Medicine: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Gels 2026, 12, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010052

Huang Q, Liu M, Ye T, Mo D, Wu H, Ma G, Zhou X. Carrier-Free Supramolecular Hydrogel Self-Assembled from Triterpenoid Saponins from Traditional Chinese Medicine: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Gels. 2026; 12(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Qiongxue, Mingzhen Liu, Tingting Ye, Dandan Mo, Haifeng Wu, Guoxu Ma, and Xiaolei Zhou. 2026. "Carrier-Free Supramolecular Hydrogel Self-Assembled from Triterpenoid Saponins from Traditional Chinese Medicine: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity" Gels 12, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010052

APA StyleHuang, Q., Liu, M., Ye, T., Mo, D., Wu, H., Ma, G., & Zhou, X. (2026). Carrier-Free Supramolecular Hydrogel Self-Assembled from Triterpenoid Saponins from Traditional Chinese Medicine: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Gels, 12(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010052