Negative and Reversible Magnetorheological Response for Magnetic Rubbers

Abstract

1. Introduction

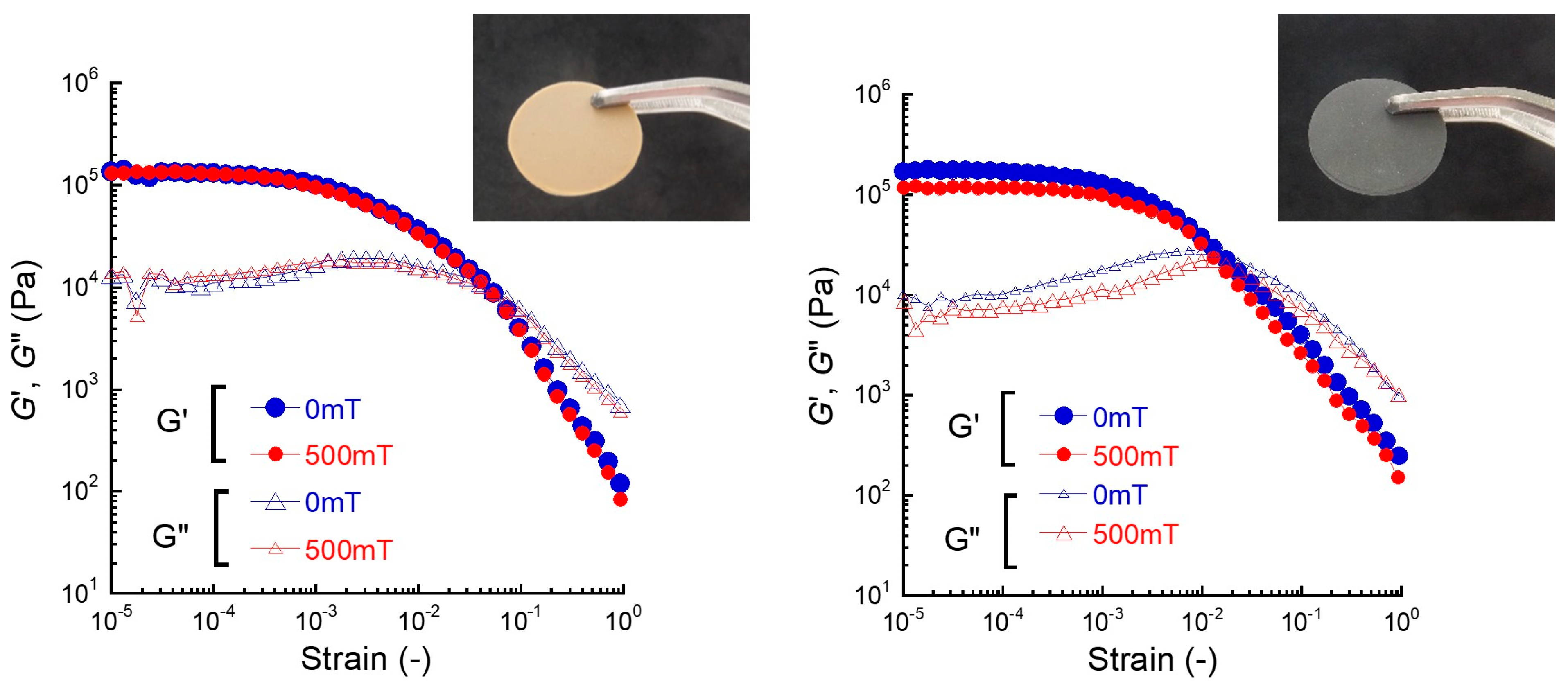

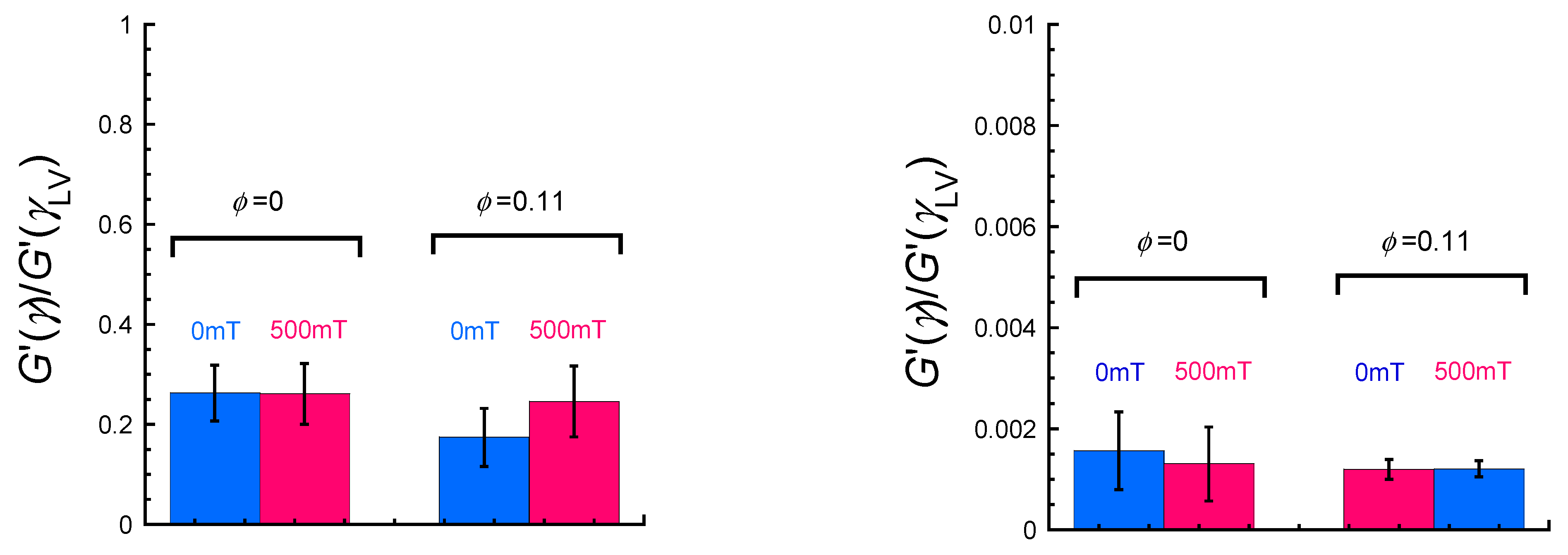

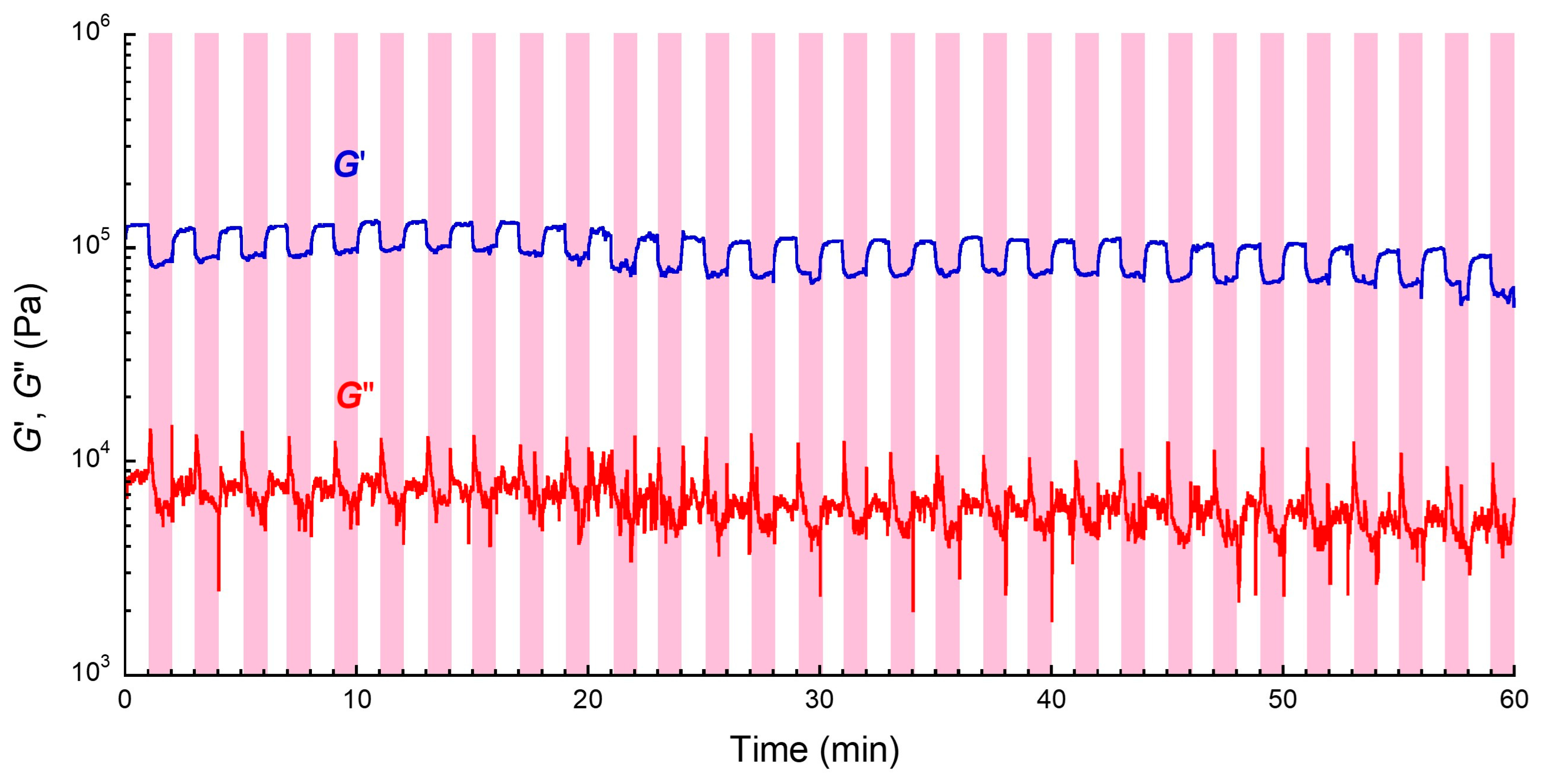

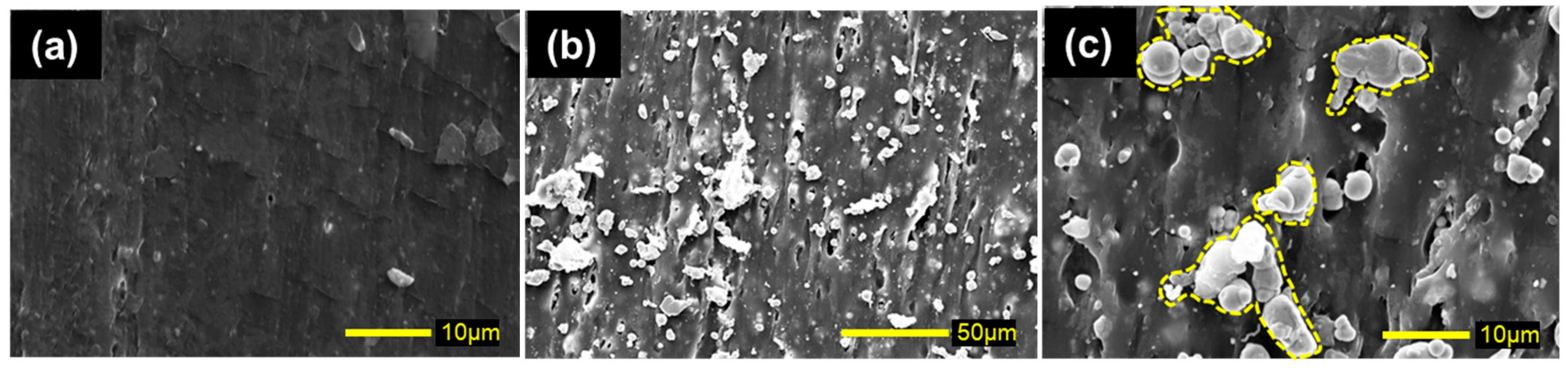

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Magnetic Rubbers and Measurement of Degree of Swelling

4.2. Dynamic Viscoelastic Measurement

4.3. Scanning Electron Microscope Observations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.J.; Niu, Q.Y.; Liu, X.; Su, L.N.; Zhang, J.H.; Meng, S.; Li, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Q.Q. Thermal responsive smart lanthanide luminescent hydrogel actuator. Opt. Mater. 2023, 142, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okihara, M.; Matsuda, A.; Kawamura, A.; Miyata, T. Design of dual stimuli-responsive gels with physical and chemical properties that vary in response to light and temperature and cell behavior on their surfaces. Polym. J. 2024, 56, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, A.; Allaf, M.R.N.; Charoghdoozi, K.; Dehghan, H.; Mahmoodabadi, S.; Bazrgaran, A.; Savoji, H.; Sedighi, M. Stimuli-responsive carrageenan-based biomaterials for biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 291, 138920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.H.; Lv, S.H.; Qiang, Y.Y.; Cao, X.Z.; He, T.X.; Liu, L.P. From preparation to application: Functional carrageenan-based hydrogels for biomedical and sensing uses. Mater. Today Chem. 2025, 45, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetting, M.C.; Peters, J.T.; Steichen, S.D.; Peppas, N.A. Stimulus-responsive hydrogels: Theory, modern advances, and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2015, 93, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckling, D. Stimuli-Responsive Gels. Gels 2018, 4, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, C.; Fernandes, S.N.; Godinho, M.H.; Borges, J.P.; Soares, P.I.P. Functional Stimuli-Responsive Gels: Hydrogels and Microgels. Gels 2018, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Ngai, T. Stimuli-responsive gel emulsions stabilized by microgel particles. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2011, 289, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuksenok, O.; Balazs, A.C. Stimuli-responsive behavior of composites integrating thermo-responsive gels with photo-responsive fibers. Mater. Horiz. 2016, 3, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Ding, J.J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Song, Z.H.; Meng, X.X.; Ma, X.T.; Gong, X.Y.; Huang, Z.X.; Ma, S.M.; et al. Components, mechanisms and applications of stimuli-responsive polymer gels. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 177, 111473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Fu, J.; Xie, Y.P.; Li, Y.P.; Gan, R.Y.; Yu, M. Versatile magnetorheological plastomer with 3D printability, switchable mechanics, shape memory, and self-healing capacity. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 183, 107817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditter, D.; Bluemler, P.; Klockner, B.; Hilgert, J.; Zentel, R. Microfluidic Synthesis of Liquid Crystalline Elastomer Particle Transport Systems which Can Be Remote-Controlled. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1902454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roghani, M.; Romeis, D.; Glavan, G.; Belyaeva, I.A.; Shamonin, M.; Saphiannikova, M. Magnetically induced deformation of isotropic magnetoactive elastomers and its relation to the magnetorheological effect. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2025, 23, 034041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Upadhyay, R.V.; Mazlan, S.A.; Nordin, N.A.; Johari, M.A.F. Magnetic field-induced dynamic viscoelastic properties of isotropic and pre-structured magnetorheological elastomers having non-spherical shaped iron particles: Impact of particle–particle and particle–matrix interactions. J. Polym. Res. 2025, 32, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.L.; Zhang, J.T.; Guo, S.J.; Zhao, Y.J.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, M.; Zhai, P.C. Magnetorheological properties of novel magnetorheological elastomers featuring tilted particle chains under quasi-static shear loading. Smart Mater. Struct. 2025, 34, 075045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeber, R.; Kreissl, P.; Holm, C. Magnetic field controlled behavior of magnetic gels studied using particle-based simulations. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berestok, T.; Chacón-Borrero, J.; Li, J.S.; Guardia, P.; Cabot, A. Crystalline Magnetic Gels and Aerogels Combining Large Surface Areas and Magnetic Moments. Langmuir 2023, 39, 3692–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, A.; Musikhin, A.; Chirikov, D. Internal structures and mechanical properties of magnetic gels and suspensions. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, 1419–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.H.; Li, Y.Y.; Wei, H.W.; Gao, G.L.; Zhang, D.W.; Jiang, Z.X. Rapidly self-healing, magnetically controllable, stretchable, smart, moldable nanoparticle composite gel. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 10586–10591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.F.; Junot, G.; Golestanian, R.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.T.; Tierno, P.; Meng, F.L. Molecular dynamics simulations of microscopic structural transition and macroscopic mechanical properties of magnetic gels. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 074902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriegl, R.; Kovalev, A.; Shamonin, M.; Gorb, S. Tunable contact angle hysteresis on compliant magnetoactive elastomers. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2023, 63, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegl, R.; Krenkel, L.; Shamonin, M. Preservation of wetting ridges using field-induced plasticity of magnetoactive elastomers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 683, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezersek, M.; Kriegl, R.; Kravanja, G.; Hribar, L.; Drevensek-Olenik, I.; Unold, H.; Shamonin, M. Control of Droplet Impact through Magnetic Actuation of Surface Microstructures. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2202471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rashid, A.; Al-Maslamani, N.A.; Abutaha, A.; Hossain, M.; Koç, M. Cobalt iron oxide (CoFe2O4) reinforced polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) based magnetoactive polymer nanocomposites for remote actuation. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 311, 117838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, I.E.; Kolesov, V.V.; Fionov, A.S.; Kramarenko, E.Y.; Stepanov, G.V.; Mikheev, M.G.; Verona, E.; Solodov, I. Magnetoactive elastomers with controllable radio-absorbing properties. Mater. Today Commun. 2019, 21, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.C.; Wang, L.S.; Li, B.J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.J. Transform commercial magnetic materials into injectable gel for magnetic hyperthermia therapy in vivo. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 224, 113185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetomi, S.; Tsumori, F. Soft Actuator with DN-gel Dispersed with Magnetic Particles. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, C.; Miwa, D.; Tanihira, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Sakurai, J.; Hata, S. Magnetic-nanoparticle-embedded “wireless” hydrogel microvalve. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2025, 78, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetomi, S.; Takahashi, H.; Tsumori, F. Magnetic Actuator Using Double Network Gel. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2020, 33, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.W.; Wu, D.; Jiang, J.J.; Wu, X.Y.; Ma, J.; Hu, X.P.; Sun, W.Q.; Liu, J. Magnetic fields improve the gel properties of myofibrillar proteins in low-salt myofibrillar protein emulsion systems. Food Chem. 2025, 470, 142681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Watanabe, M.; Takeda, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Uesugi, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Suzuki, M.; Uesugi, K.; Yasutake, M.; Kawai, M.; et al. In Situ Observation of the Movement of Magnetic Particles in Polyurethane Elastomer Densely Packed Magnetic Particles Using Synchrotron Radiation X-ray Computed Tomography. Langmuir 2022, 38, 13497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillas, J.R.; de Vicente, J. Magnetorheology: A review. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 9614–9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Choi, K.; Nam, J.D.; Choi, H.J. Magnetic Polymer Composite Particles: Design and Magnetorheology. Polymers 2021, 13, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadzharyan, T.A.; Shamonin, M.; Kramarenko, E.Y. Theoretical Modeling of Magnetoactive Elastomers on Different Scales: A State-of-the-Art Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsumata, T.; Sakai, K.; Takimoto, J. Giant Reduction in Dynamic Modulus of K-Carrageenan Magnetic Gel. J. Phys. Chem. 2006, 110, 20217–20223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsumata, T.; Nagata, A.; Sakai, K.; Takimoto, J. Giant Complex Modulus Reduction of κ-Carrageenan Magnetic Gels. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2005, 26, 1538–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsumata, T.; Wakabayashi, T.; Okazaki, T. Particle Dispersibility and Giant Reduction in Dynamic Modulus of Magnetic Gels Containing Barium Ferrite and Iron Oxide Particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 14132–14139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsumata, T.; Honda, A.; Kanazawa, H.; Kawai, M. Magnetically Tunable Elasticity for Magnetic Hydrogels Consisting of Carrageenan and Carbonyl Iron Particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 12341–12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsumata, T.; Ohori, S. Magnetic polyurethane elastomers with wide range modulation of elasticity. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujiei, Y.; Akama, S.; Ikeda, J.; Takeda, Y.; Kawai, M.; Mitsumata, T. Particle Dispersibility and sound propagation of ultrasounds for magnetic soft composites. React. Funct. Polym. 2018, 130, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordina, B.; Tiwari, R.K.; Setua, D.K.; Sharma, A. Impact of graphene oxide on the magnetorheological behaviour of BaFe12O19 nanoparticles filled polyacrylamide hydrogel. Polymer 2016, 97, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.R. A note on the existence of a yield point in the dynamic modulus of loaded vulcanizates. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1960, 3, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Song, Y.H.; Zheng, Q.; Tan, H.; Yu, J.; Li, H. Nonlinear Rheological Behavior of Silica Filled Solution-Polymerized Styrene Butadiene Rubber. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2007, 45, 2594–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.Y.; Du, M.; Xiao, J.L.; Song, Y.H.; Zheng, Q. Revealing the three-dimensional filler structure in a rubber matrix based on fluorescein modified layered double hydroxides. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4030–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wang, L. Research on Payne effect of natural rubber reinforced by graft-modified silica. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 43891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.H.; Yang, L.; Shi, X.Y.; Yu, X.F.; Xu, Z.; Song, Y.H.; Zuo, M.; Zheng, Q. Influence of axial pressure on the Payne effect of natural rubber vulcanizates. Polymer 2024, 303, 127103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urano, R.; Kawai, M.; Mitsumata, T. Voids induce wide-range modulation of elasticity for magnetic elastomers II. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 8091–8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorokin, V.V.; Stepanov, G.V.; Shamonin, M.; Monkman, G.J.; Khokhlov, A.R.; Kramarenko, E.Y. Hysteresis of the viscoelastic properties and the normal force in magnetically and mechanically soft magnetoactive elastomers: Effects of filler composition, strain amplitude and magnetic field. Polymer 2015, 76, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaeva, I.A.; Kramarenko, E.Y.; Shamonin, M. Magnetodielectric effect in magnetoactive elastomers: Transient response and hysteresis. Polymer 2017, 127, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavan, G.; Belyaeva, I.A.; Drevensek-Olenik, I.; Shamonin, M. Experimental study of longitudinal, transverse and volume strains of magnetoactive elastomeric cylinders in uniform magnetic fields. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 579, 170826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanamori, R.; Sako, T.; Okazaki, H.; Kawai, M.; Mitsumata, T. Negative and Reversible Magnetorheological Response for Magnetic Rubbers. Gels 2025, 11, 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120969

Kanamori R, Sako T, Okazaki H, Kawai M, Mitsumata T. Negative and Reversible Magnetorheological Response for Magnetic Rubbers. Gels. 2025; 11(12):969. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120969

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanamori, Rentaro, Tomoya Sako, Hiroaki Okazaki, Mika Kawai, and Tetsu Mitsumata. 2025. "Negative and Reversible Magnetorheological Response for Magnetic Rubbers" Gels 11, no. 12: 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120969

APA StyleKanamori, R., Sako, T., Okazaki, H., Kawai, M., & Mitsumata, T. (2025). Negative and Reversible Magnetorheological Response for Magnetic Rubbers. Gels, 11(12), 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120969