Acidification and Calcium Addition Effects on High-Pressure and Thermally Induced Pulse Protein Gels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

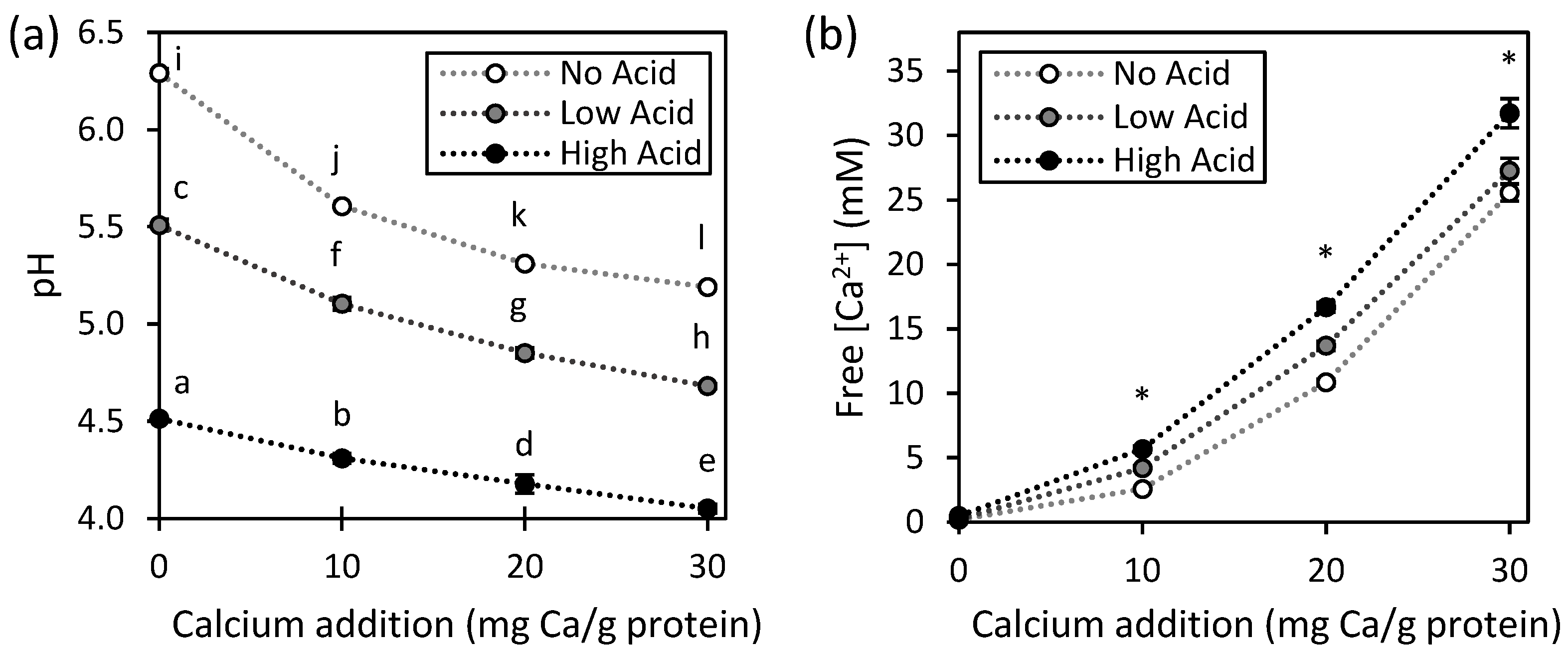

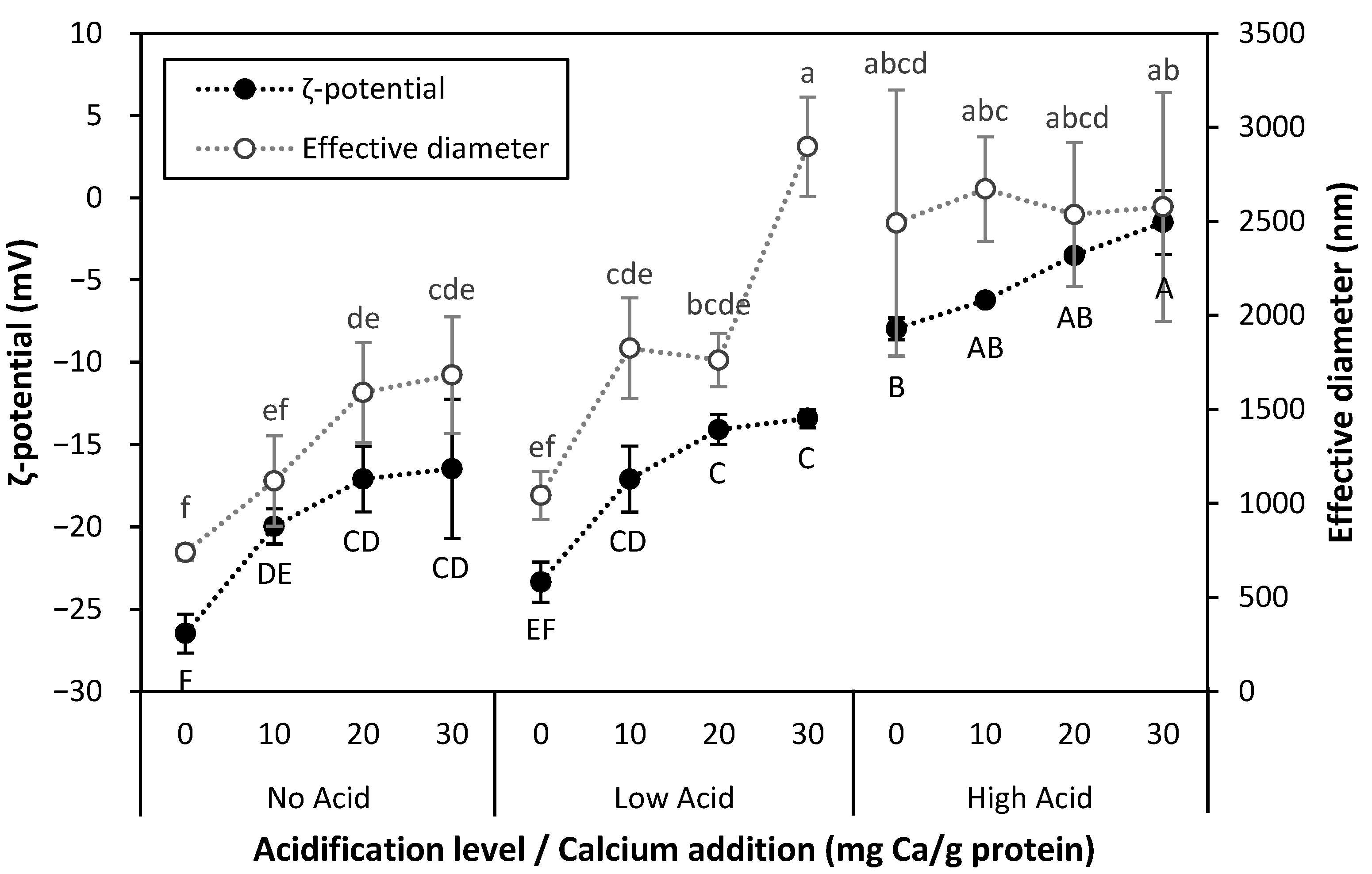

2.1. Properties and Stability of Pulse Protein Concentrate Suspensions Prior to Processing

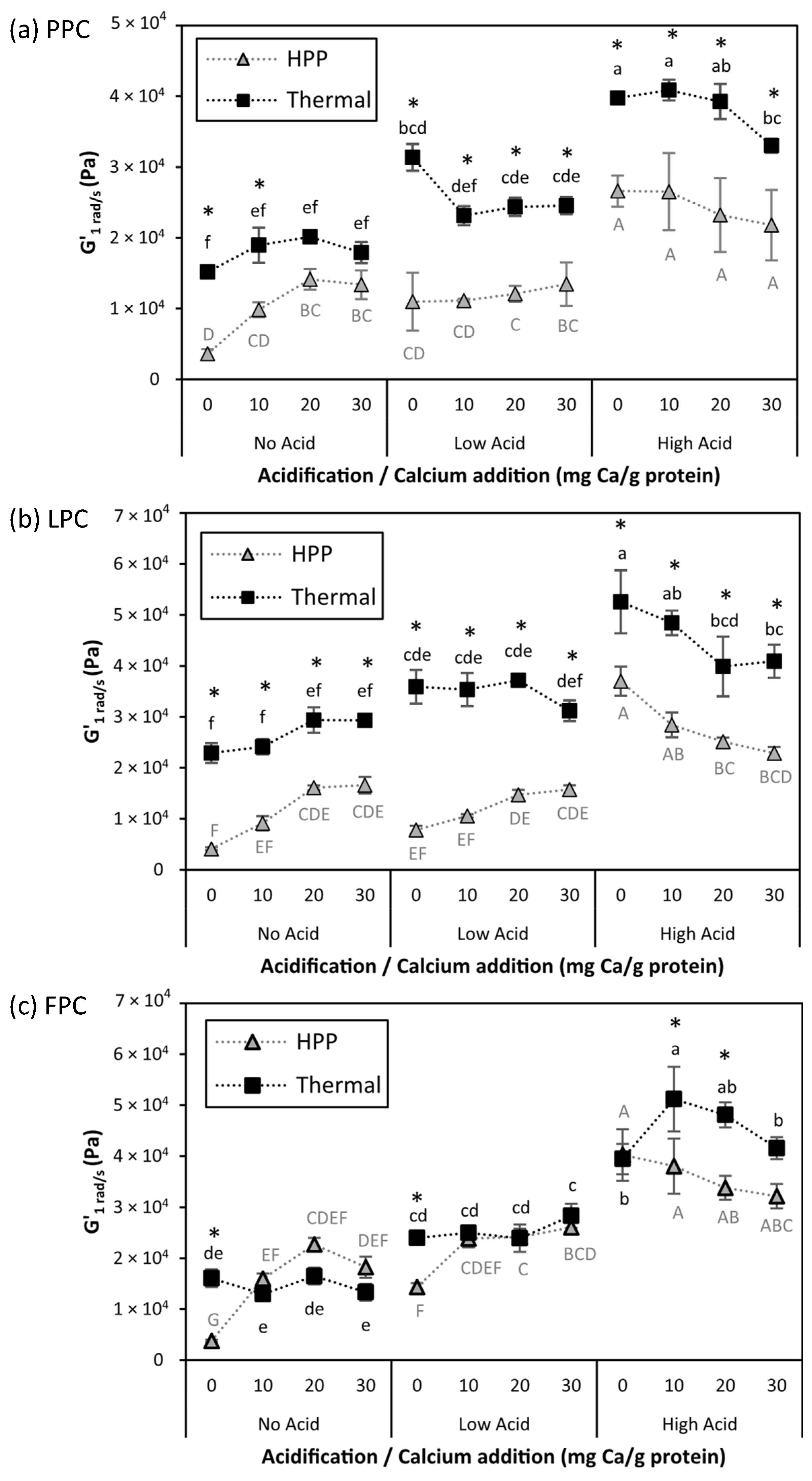

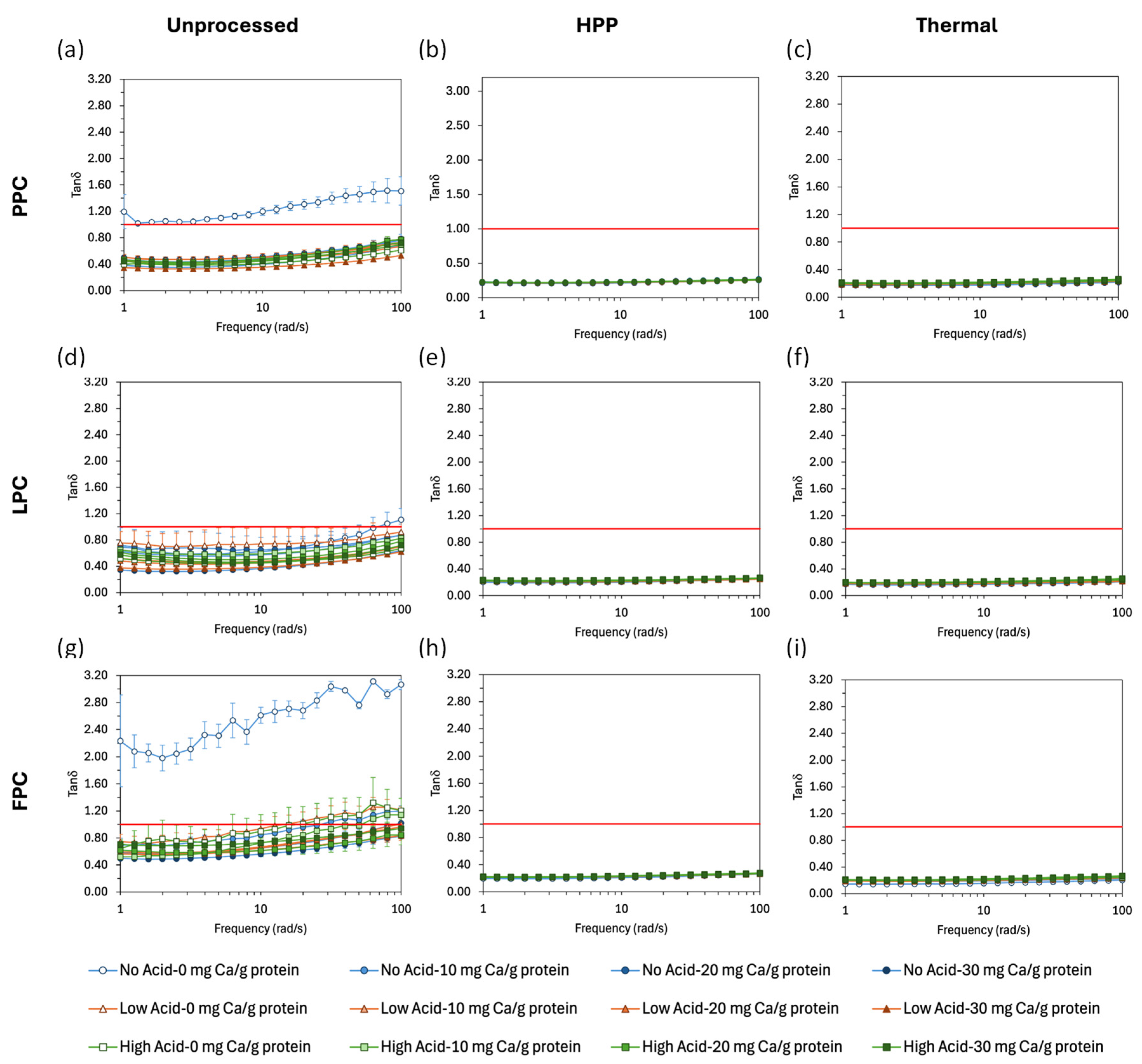

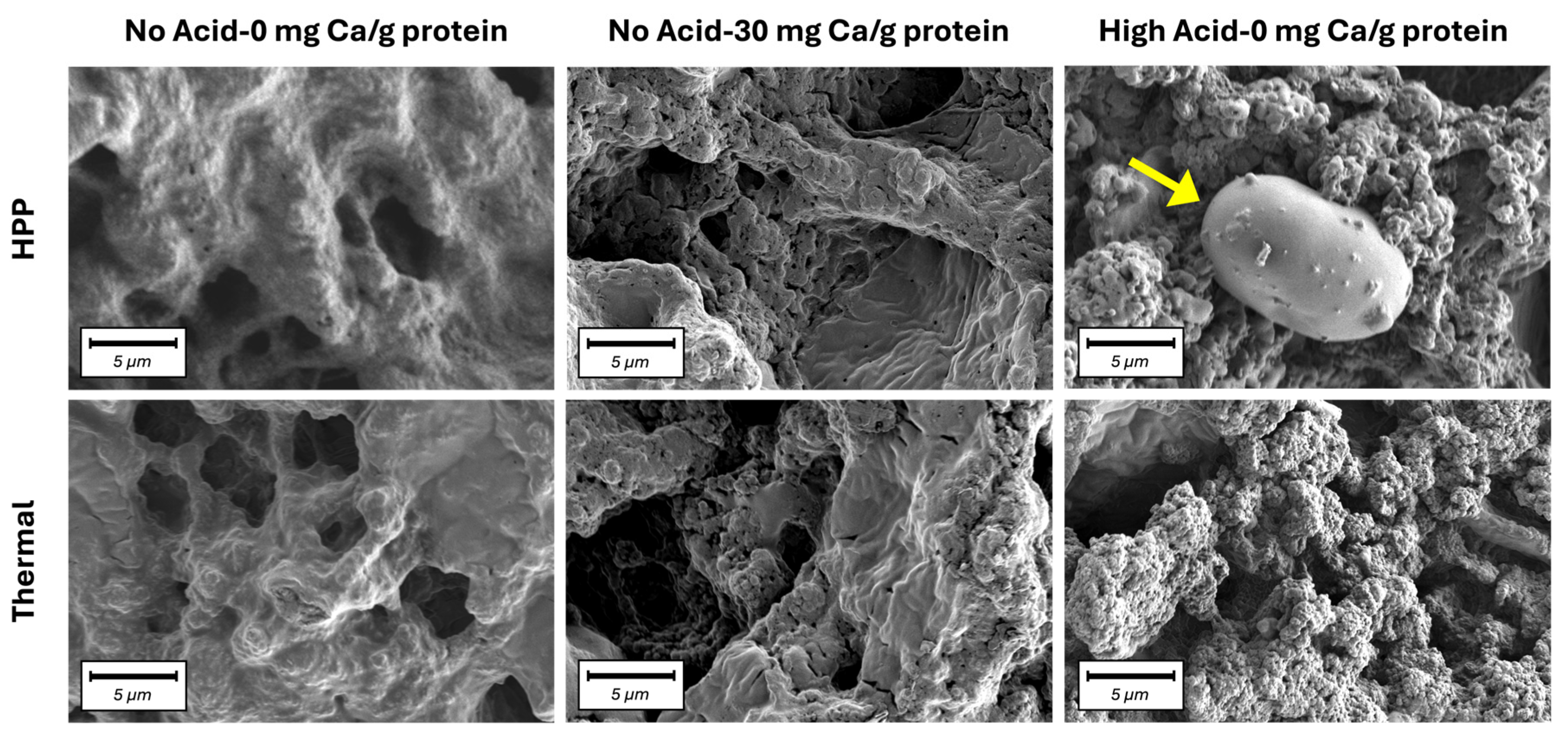

2.2. Effect of Process Type, Acidification, and Calcium Addition on the Rheological Properties and Microstructure of Pulse Protein Concentrate Gels

2.3. Effect of Process Type, Acidification, and Calcium Addition on the Textural Properties and Macrostructure of Pulse Protein Concentrate Gels

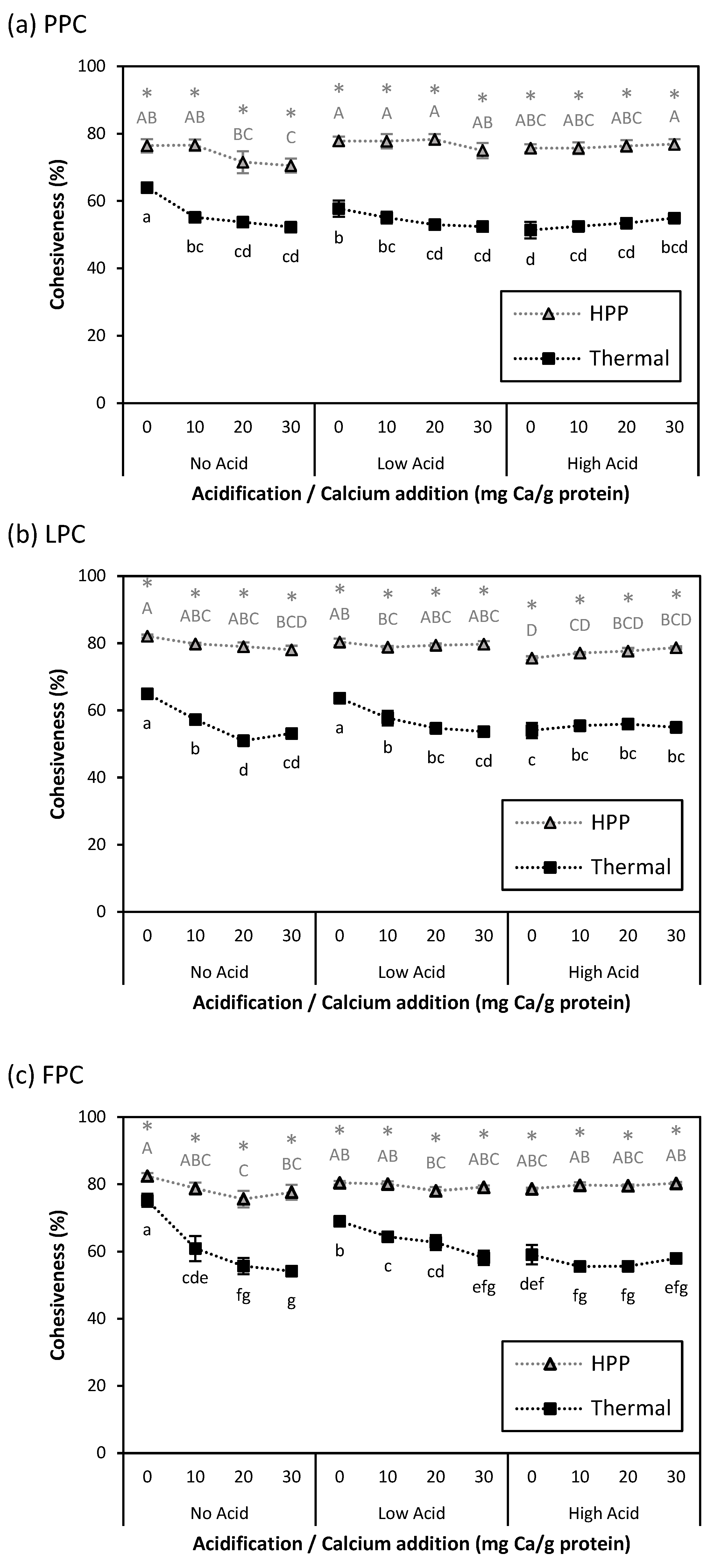

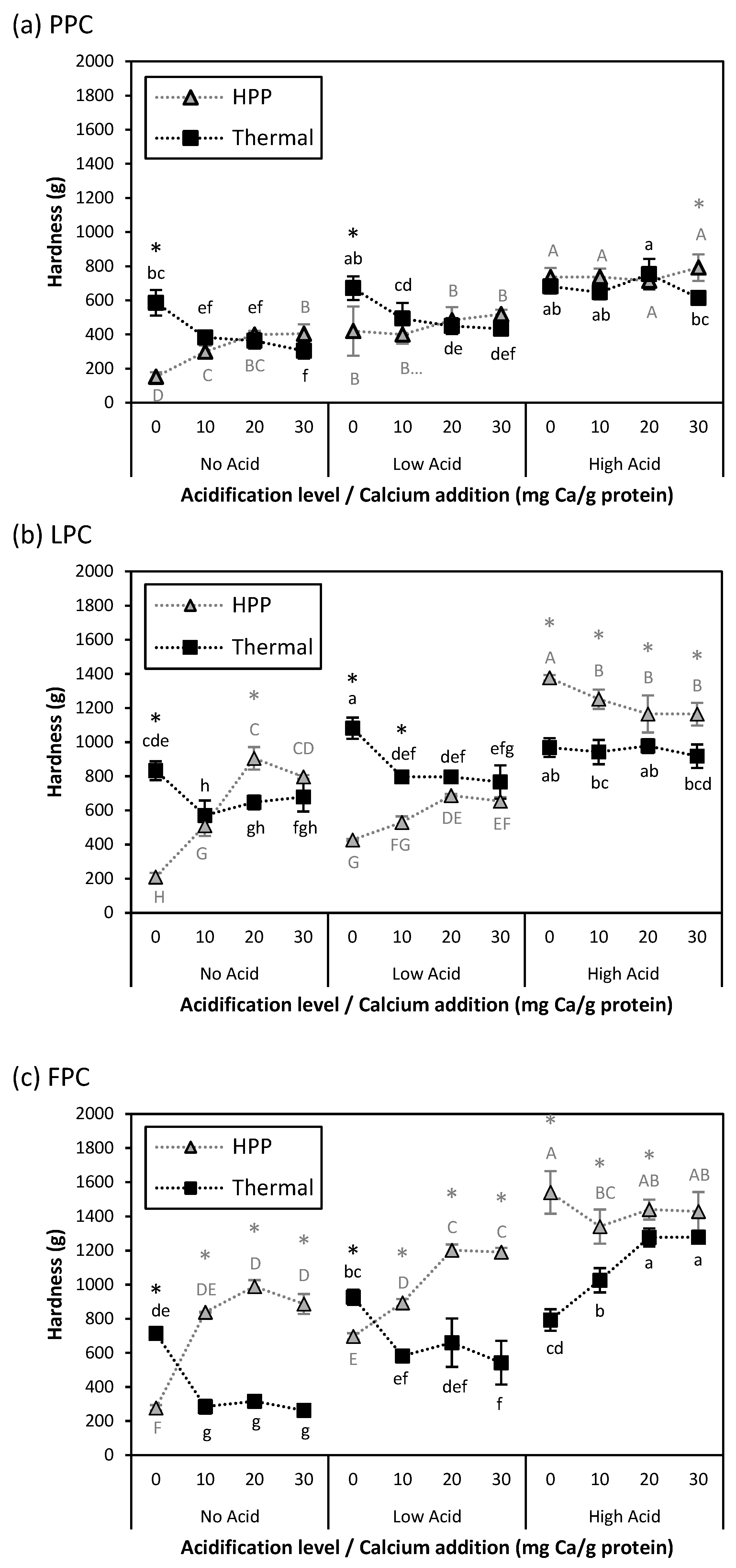

2.3.1. Gel Cohesiveness and Hardness

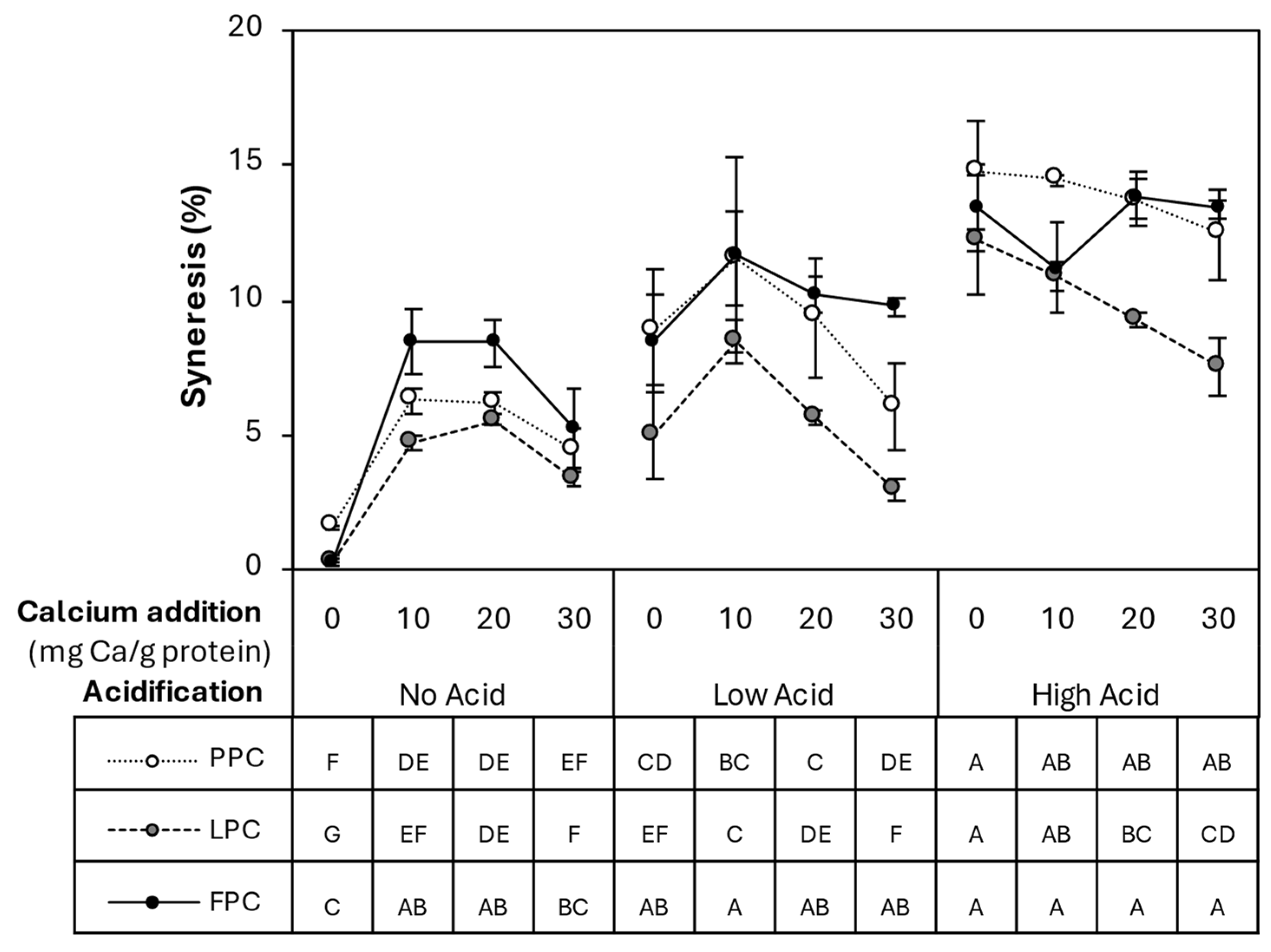

2.3.2. Gel Water Holding Capacity and Syneresis

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Protein Concentrate Suspensions

4.3. High-Pressure Processing

4.4. Thermal Processing

4.5. Particle Size and Zeta Potential Measurements

4.6. Free Ca2+ Measurements

4.7. pH Measurements

4.8. Rheological Analysis

4.9. Texture Profile Analysis

4.10. Water Holding Capacity

4.11. Spontaneous Syneresis

4.12. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.13. Macroscopic Visual Examination of Gel Cross-Section

4.14. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPC | Pea protein concentrate |

| LPC | Lentil protein concentrate |

| FPC | Faba bean protein concentrate |

| HPP | High-pressure processing |

References

- Boye, J.; Zare, F.; Pletch, A. Pulse proteins: Processing, characterization, functional properties and applications in food and feed. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondor, M.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J. Processing Technologies to Produce Plant Protein Concentrates and Isolates. In Plant Protein Foods; Manickavasagan, A., Lim, L.-T., Ali, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 61–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totosaus, A.; Montejano, J.G.; Salazar, J.A.; Guerrero, I. A review of physical and chemical protein-gel induction. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 37, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mession, J.-L.; Chihi, M.L.; Sok, N.; Saurel, R. Effect of globular pea proteins fractionation on their heat-induced aggregation and acid cold-set gelation. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 46, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackis, J.J.; Sessa, D.J.; Honig, D.H. Flavor problems of vegetable food proteins. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1979, 56, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolmson, L.; Frohlich, P.; Boux, G.; Bellido, A.-S.; Boye, J.; Warkentin, T.D. Aroma and flavour properties of Saskatchewan grown field peas (Pisum sativum L.). Can. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 94, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzav, H.; Chirug, L.; Okun, Z.; Davidovich-Pinhas, M.; Shpigelman, A. Comparison of Thermal and High-Pressure Gelation of Potato Protein Isolates. Foods 2020, 9, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Moraru, C.I. High-pressure structuring of milk protein concentrate: Effect of pH and calcium. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 4074–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.E.; Moraru, C.I. Structure and function of pea, lentil and faba bean proteins treated by high pressure processing and heat treatment. LWT 2021, 152, 112349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Powers, J.R. Effects of High Pressure on Food Proteins. In High Pressure Processing of Food: Principles, Technology and Applications; Balasubramaniam, V.M., Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V., Lelieveld, H.L.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 353–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, J.; Caro, J.A.; Norberto, D.R.; Barthe, P.; Roumestand, C.; Schlessman, J.L.; Garcia, A.E.; García-Moreno, B.E.; Royer, C.A. Cavities determine the pressure unfolding of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6945–6950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonyaratanakornkit, B.B.; Park, C.B.; Clark, D.S. Pressure effects on intra- and intermolecular interactions within proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 2002, 1595, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.I.; Umair, M.; Mathur, Y.; Mohammad, T.; Khan, A.; Sulaimani, M.N.; Alam, A.; Islam, A. Molecular Dynamics Simulation to Study Thermal Unfolding in Proteins. In Protein Folding Dynamics and Stability: Experimental and Computational Methods; Saudagar, P., Tripathi, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balny, C.; Masson, P. Effects of high pressure on proteins. Food Rev. Int. 1993, 9, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Tay, S.; Yao Tan, H.; Perera, C. The Coagulating Effects of Cations and Anions on Soy Protein. Int. J. Food Prop. 2006, 9, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevkani, K.; Singh, N.; Chen, Y.; Kaur, A.; Yu, L. Pulse proteins: Secondary structure, functionality and applications. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 2787–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usaga, J.; Acosta, Ó.; Churey, J.J.; Padilla-Zakour, O.I.; Worobo, R.W. Evaluation of high pressure processing (HPP) inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, and Listeria monocytogenes in acid and acidified juices and beverages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 339, 109034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitzer, K.S. Thermodynamics of electrolytes. I. Theoretical basis and general equations. J. Phys. Chem. 1973, 77, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinacci, A.; Peyrano, F.; Scilingo, A.; Piermaria, J.; Speroni, F. Modification of Techno-Functional Properties of Plant Proteins Through Combined Calcium Addition and High Hydrostatic Pressure: A Review With Emphasis on Soybean and Cowpea. Sustain. Food Proteins 2025, 3, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.Y.J.; Moraru, C.I. High-pressure processing of pea protein–starch mixed systems: Effect of starch on structure formation. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.Y.J.; Karwe, M.V.; Moraru, C.I. High pressure structuring of pea protein concentrates. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.D.; Arntfield, S.D. Gelation properties of salt-extracted pea protein isolate induced by heat treatment: Effect of heating and cooling rate. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H. Thermal denaturation and gelation of vicilin-rich protein isolates from three Phaseolus legumes: A comparative study. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 41, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T.; Katho, S.; Mothizuki, K. Influences of Calcium and pH on Protein Solubility in Soybean Milk. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1993, 57, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marolt, G.; Gričar, E.; Pihlar, B.; Kolar, M. Complex Formation of Phytic Acid With Selected Monovalent and Divalent Metals. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 582746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, R.D. Effect of pH on the binding of calcium ions by soybean proteins. Cereal Chem. 1984, 61, 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Xia, W.; Gunes, D.Z.; Ahrné, L. Heat-induced gels from pea protein soluble colloidal aggregates: Effect of calcium addition or pH adjustment on gelation behavior and rheological properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, H.; Bansal, N.; Bhandari, B. Effects of milk pH alteration on casein micelle size and gelation properties of milk. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Pandit, S.; Abbas, S.; Aswal, V.K.; Kohlbrecher, J. Structures and interactions among globular proteins above the isoelectric point in the presence of divalent ions: A small angle neutron scattering and dynamic light scattering study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 693, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Ayad, A.; Ramaswamy, H.S.; Alli, I.; Shao, Y. Dynamic Viscoelastic Behavior of High Pressure Treated Soybean Protein Isolate Dispersions. Int. J. Food Prop. 2007, 10, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, E.; Defaye, A.B.; Ledward, D.A. Soy protein pressure-induced gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2002, 16, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Hayashi, R. Application of High Pressure to Food Processing: Textural Comparison of Pressure- and Heat-induced Gels of Food Proteins. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1990, 54, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrano, F.; de Lamballerie, M.; Avanza, M.V.; Speroni, F. High hydrostatic pressure- or heat-induced gelation of cowpea proteins at low protein content: Effect of calcium concentration. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrano, F.; de Lamballerie, M.; Avanza, M.V.; Speroni, F. Gelation of cowpea proteins induced by high hydrostatic pressure. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 111, 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.E.; Moraru, C.I. Comparative effects of high pressure processing and heat treatment on in vitro digestibility of pea protein and starch. npj Sci. Food 2022, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speroni, F.; Jung, S.; De Lamballerie, M. Effects of Calcium and Pressure Treatment on Thermal Gelation of Soybean Protein. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, E30–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldiken, B.; Stobbs, J.; Nickerson, M. Heat induced gelation of pulse protein networks. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manassero, C.A.; Vaudagna, S.R.; Añón, M.C.; Speroni, F. High hydrostatic pressure improves protein solubility and dispersion stability of mineral-added soybean protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, L.; Scilingo, A.; Speroni, F. Thermal Versus High Hydrostatic Pressure Treatments on Calcium-added Soybean Proteins. Protein Solubility, Colloidal Stability and Cold-set Gelation. Food Biophys. 2019, 14, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbonaite, V.; van der Kaaij, S.; de Jongh, H.H.J.; Scholten, E.; Ako, K.; van der Linden, E.; Pouvreau, L. Relation between gel stiffness and water holding for coarse and fine-stranded protein gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 56, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, J.M.S. Relations between rheological properties and network structure of soy protein gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2004, 18, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, E.; Havea, P.; McCarthy, O.; Watkinson, P.; Singh, H. Behavior of Protein in the Presence of Calcium during Heating of Whey Protein Concentrate Solutions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 13156–13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcenilla, B.; Román, L.; Martínez, C.; Martínez, M.M.; Gómez, M. Effect of high pressure processing on batters and cakes properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 33, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; de Campo, L.; Gilbert, E.P.; Knott, R.; Cheng, L.; Storer, B.; Lin, X.; Luo, L.; Patole, S.; Hemar, Y. Effect of NaCl and CaCl2 concentration on the rheological and structural characteristics of thermally-induced quinoa protein gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyńska-Mleko, M.; Terpiłowski, K.; Mleko, S.; Kwiatkowski, C.; Kawecka-Radomska, M. Surface Properties of Aerated Ion-induced Whey Protein Gels. Food Biophys. 2015, 10, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, D.; Pinho, L.; Patel, B.; Desam, P.; Campanella, O.H. Characterization of starch–water interactions and their effects on two key functional properties: Starch gelatinization and retrogradation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 39, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein has biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein has biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein has biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein has biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

) samples. Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, each being an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein had only biological duplicates, due to a sample loss.

) samples. Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, each being an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein had only biological duplicates, due to a sample loss.

) samples. Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, each being an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein had only biological duplicates, due to a sample loss.

) samples. Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, each being an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein had only biological duplicates, due to a sample loss.

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein have biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein have biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein have biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

). Values represent averages of independent biological triplicates, which are each an average of technical triplicates. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences within HPP- and thermally processed samples, respectively. Within the same acidification and calcium addition level, * indicates significant difference between process types. PPC-High Acid-0 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-10 mg Ca/g protein, PPC-High Acid-20 mg Ca/g protein have biological duplicates due to a sample loss.

| Acidification | Calcium (mg Ca/g Protein) | Water Holding Capacity (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC | LPC | FPC | ||||||||

| Unprocessed | HPP | Thermal | Unprocessed | HPP | Thermal | Unprocessed | HPP | Thermal | ||

| No Acid | 0 | 41.6 ± 1.7 b, E | 94.2 ± 0.7 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 40.3 ± 0.7 b, F | 94.3 ± 0.8 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 35.6 ± 0.1 c, D | 92.8 ± 1.6 b, AB | 100 ± 0 a, A |

| 10 | 65.5 ± 1.2 c, CD | 91.3 ± 2.3 b, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 56.9 ± 3.4 c, E | 90.2 ± 1.7 b, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 50.8 ± 1.3 c, C | 87.4 ± 1.1 b, C | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| 20 | 68.1 ± 2.9 b, BCD | 94.2 ± 2.7 a, A | 99.8 ± 0.2 a, A | 71.6 ± 2.8 b, ABC | 91.9 ± 1.3 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 55 ± 2.9 c, BC | 92 ± 1.5 b, ABC | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| 30 | 74.3 ± 3.1 b, AB | 93.2 ± 2 a, A | 99.9 ± 0.1 a, A | 62 ± 10.4 b, DE | 95.9 ± 1 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 67.1 ± 0.8 c, A | 90.2 ± 2.6 b, ABC | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| Low Acid | 0 | 64.2 ± 5.1 c, D | 91.6 ± 2 b, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 56 ± 5.2 c, E | 88.5 ± 0.9 b, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 55.5 ± 0.4 c, BC | 88 ± 1.1 b, BC | 100 ± 0 a, A |

| 10 | 65.3 ± 4.3 b, D | 95.4 ± 2.2 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 65.5 ± 1.4 c, CD | 89.9 ± 0.9 b, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 53.1 ± 0.8 c, BC | 89.4 ± 1.3 b, ABC | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| 20 | 68.3 ± 3 b, BCD | 94 ± 2.8 a, A | 99.9 ± 0.1 a, A | 72.5 ± 1.5 b, ABC | 92.3 ± 0.7 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 54.8 ± 1.6 c, BC | 93.3 ± 2.7 b, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| 30 | 77 ± 3.8 b, A | 95.2 ± 2.7 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 78.9 ± 1.4 b, A | 93.1 ± 0.6 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 64.3 ± 1.4 c, A | 93.8 ± 1.4 b, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| High Acid | 0 | 67.1 ± 2.1 b, BCD | 96.7 ± 2.2 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 66.6 ± 1.8 b, CD | 93 ± 0.6 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 55.4 ± 0.8 c, BC | 92.1 ± 2 b, ABC | 100 ± 0 a, A |

| 10 | 69.7 ± 1.5 b, ABCD | 95.1 ± 2.8 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 69 ± 0.7 b, BCD | 93.2 ± 1 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 55.8 ± 0.7 c, BC | 92.5 ± 2 b, ABC | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| 20 | 73.7 ± 3.4 b, ABC | 96.4 ± 2.2 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 72.6 ± 1.1 b, ABC | 93.4 ± 0.9 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 58.2 ± 0.8 c, BC | 90.9 ± 1.8 b, ABC | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| 30 | 74.2 ± 3.3 b, AB | 95.6 ± 2.4 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 77 ± 1.6 b, AB | 93.3 ± 0.3 a, A | 100 ± 0 a, A | 63.6 ± 2.6 c, A | 90.3 ± 1.3 b, ABC | 100 ± 0 a, A | |

| Sample | Process | Additional Treatment | Gel Strength (G′) | Gel Hardness | Gel Cohesiveness | Syneresis Post-Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pea (PPC) | HPP | Acidification | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | - | ↑↑ |

| Ca addition | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | - | ||

| Acid + Ca | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | - | ↑↑ | ||

| Thermal | Acidification | ↑↑ | - | ↓ | None observed | |

| Ca addition | - | ↓ | ↓ | None observed | ||

| Acid + Ca | ↑ | - | ↓ | None observed | ||

| Lentil (LPC) | HPP | Acidification | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ | ↑↑ |

| Ca addition | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ||

| Acid + Ca | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ||

| Thermal | Acidification | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↓ | None observed | |

| Ca addition | - | ↓ | ↓ | None observed | ||

| Acid + Ca | ↑ | - | ↓ | None observed | ||

| Faba (FPC) | HPP | Acidification | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | - | ↑↑ |

| Ca addition | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | - | ||

| Acid + Ca | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | - | ↑↑ | ||

| Thermal | Acidification | ↑ | - | ↓ | None observed | |

| Ca addition | - | ↓↓ | ↓ | None observed | ||

| Acid + Ca | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | None observed |

| PPC | LPC | FPC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients (g/100 g) | |||

| Protein | 52.8 | 49.0 | 60.1 |

| Simple Sugars | 11.8 | 8.9 | 7 |

| Starch | 5.7 | 18.9 | 6.3 |

| Moisture | 8.2 | 7.6 | 7.8 |

| Crude Fat | 2.66 | 1.7 | 1.77 |

| Ash | 5.64 | 4.94 | 6.66 |

| Minerals (mg/100 g) | |||

| Sodium | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Potassium | 1690 | 1480 | 1970 |

| Calcium | 100 | 40 | 90 |

| Sulfur | 390 | 340 | 370 |

| Chloride | 120 | 110 | 100 |

| Magnesium | 230 | 130 | 230 |

| Phosphorus | 750 | 670 | 930 |

| Iron | 5.0 | 6.9 | 5.9 |

| Zinc | 5.9 | 6.5 | 10.1 |

| Copper | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| Manganese | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Sample | Protein (g/100 g) | Starch (g/100 g) | Crude Fat (g/100 g) | Ash (g/100 g) | Total Solids (g/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC | 15.00 | 1.62 | 0.76 | 1.60 | 26.08 |

| LPC | 15.00 | 5.79 | 0.52 | 1.51 | 28.32 |

| FPC | 15.00 | 1.57 | 0.44 | 1.66 | 23.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, A.; Moraru, C.I. Acidification and Calcium Addition Effects on High-Pressure and Thermally Induced Pulse Protein Gels. Gels 2025, 11, 971. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120971

Huang A, Moraru CI. Acidification and Calcium Addition Effects on High-Pressure and Thermally Induced Pulse Protein Gels. Gels. 2025; 11(12):971. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120971

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, April, and Carmen I. Moraru. 2025. "Acidification and Calcium Addition Effects on High-Pressure and Thermally Induced Pulse Protein Gels" Gels 11, no. 12: 971. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120971

APA StyleHuang, A., & Moraru, C. I. (2025). Acidification and Calcium Addition Effects on High-Pressure and Thermally Induced Pulse Protein Gels. Gels, 11(12), 971. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120971