Preparation of Dual-Network Hydrogels and Their Application in Flexible Electronics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Construction of Dual-Network Hydrogels

2.1. Physical Crosslinking

2.1.1. Hydrogen Bonding

2.1.2. Ionic Interactions

2.1.3. Metal Coordination

| Preparation Method | Characteristic | Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | Non-covalent Forces Reversible Directional | High self-healing efficiency (93.3%) Enhanced fracture elongation (635.42%) Excellent biocompatibility | [15,16,17] |

| Ionic Interactions | Electrostatic Interactions Reversible Non-directional Susceptible to ionic strength | Rapid Gelation Excellent Conductivity Strong Adhesion | [20,21,22] |

| Metal Coordination | High-strength Bonds Partially Reversible Directional Metal ion-sensitive | Excellent Conductivity (134.11 mS cm−1, 3.28 S m−1) High Tensile Strength (2.201 MPa, 0.92 MPa) Structural Stability | [24,25,26] |

2.2. Chemical Crosslinking

2.2.1. Free Radical Polymerization Crosslinking

2.2.2. Enzymatic Crosslinking

2.2.3. Photopolymerization Crosslinking

2.2.4. Click Chemistry Crosslinking

| Preparation Method | Characteristic | Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Radical Polymerization Crosslinking | Irreversible Covalent Bonds High Bond Energy Stable Network Structure | Easily tunable reaction conditions customizable hydrogel functionalities. | [32,33,34] |

| Enzymatic Crosslinking | Irreversible/Dynamically Reversible Covalent Bonds Mild Reaction Conditions | Excellent Biocompatibility Controllable Reaction Kinetics | [38,39,40] |

| Photopolymerization Crosslinking | Irreversible Covalent Bonds Spatially and Temporally Controlled Polymerization | Rapid prototyping low-temperature processing | [43,44,45] |

| Click Chemistry Crosslinking | Dynamically Reversible Covalent Bonds Requires No Complex Catalyst Minimal Byproducts | Simple and Rapid Reaction Outstanding Self-Healing Capability (95.69% recovery within 25 min at room temperature) | [51,52,53] |

2.3. Physico-Chemical Hybrid Crosslinking

3. Performance Optimization of Dual-Network Hydrogels

3.1. Nanocellulose

3.1.1. Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC)

3.1.2. Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF)

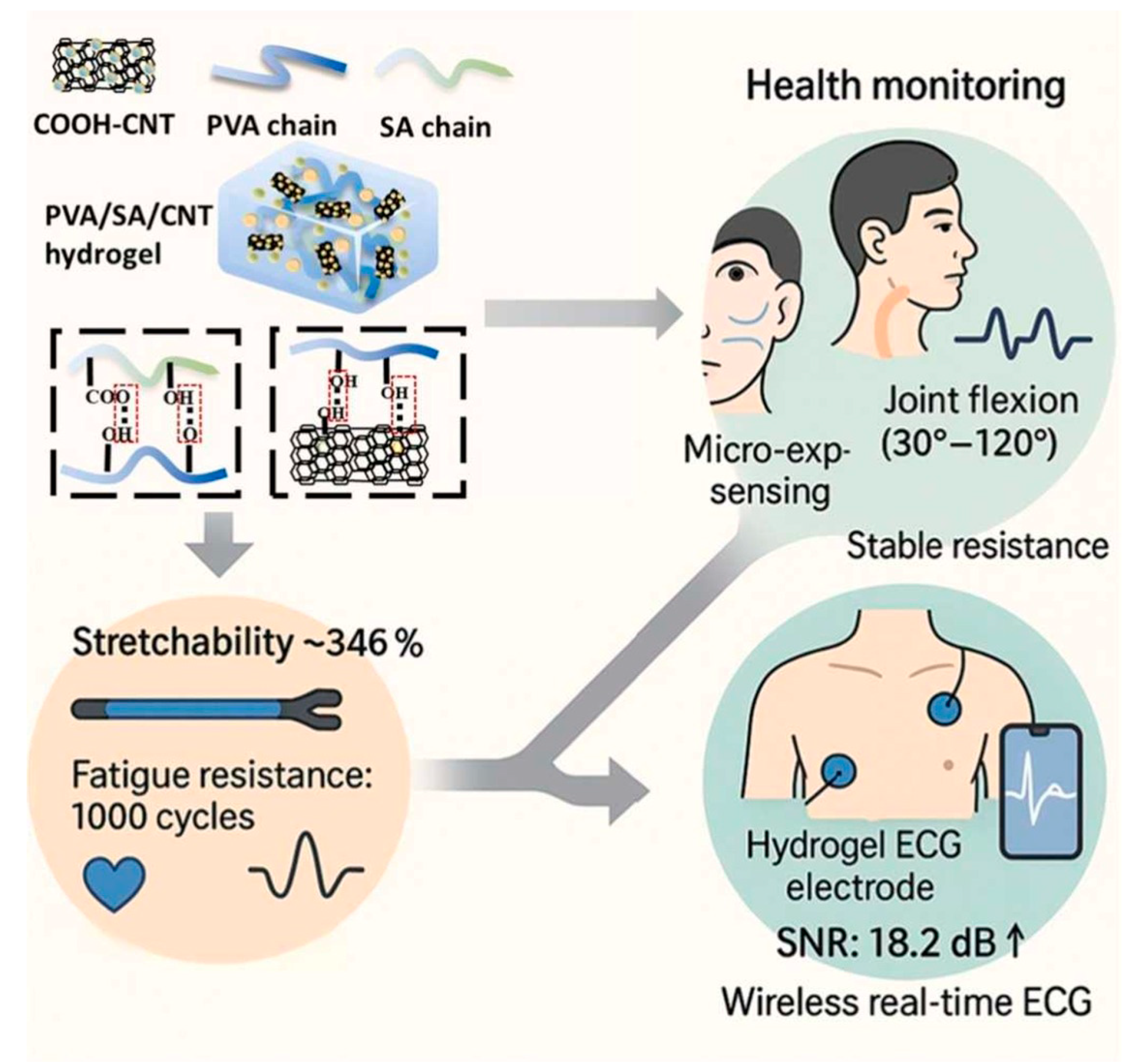

3.2. Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

| Performance Optimization Filler Type | Specific Filler Types | Characteristics | Specific Performance Optimization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocellulose | Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC) | Rod-like/Needle-shaped High Crystallinity Hydroxyl-rich Surface | Enhancing tensile strength (1.6 MPa) high sensitivity (GF = 2.97) fast response time (229.2 ms) Optimizing the stability of the hydrogel network | [59,60,61] |

| Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF) | High Aspect Ratio Good Flexibility Hydroxyl-rich Surface Renewable | Improving the toughness (200 kJ/m3) Enhancing the stretchability (285 kPa) self-healing ability thermal stability of hydrogels. | [64,65,66] | |

| Carbon Materials | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High electrical conductivity ultrahigh tensile strength lightweight flexibility | Improving electrical conductivity enhancing mechanical strength (0.12 MPa) increasing sensing sensitivity (GF = 0.12 for 40–100% strain; GF = 0.24 for 100–250% strain) | [71,72,73] |

| 2D Transition Metal Carbides/Nitrides | MXene | High electrical conductivity layered structure surface polar functional groups | Multi-functional integration Improving electrical conductivity Enhancing mechanical strength Enhancing EMI shielding performance Boosting the self-healing capability | [74,75,76] |

3.3. MXene

4. Applications in Flexible Electronic Devices

4.1. Bodily Fluid Biomarker Sensors

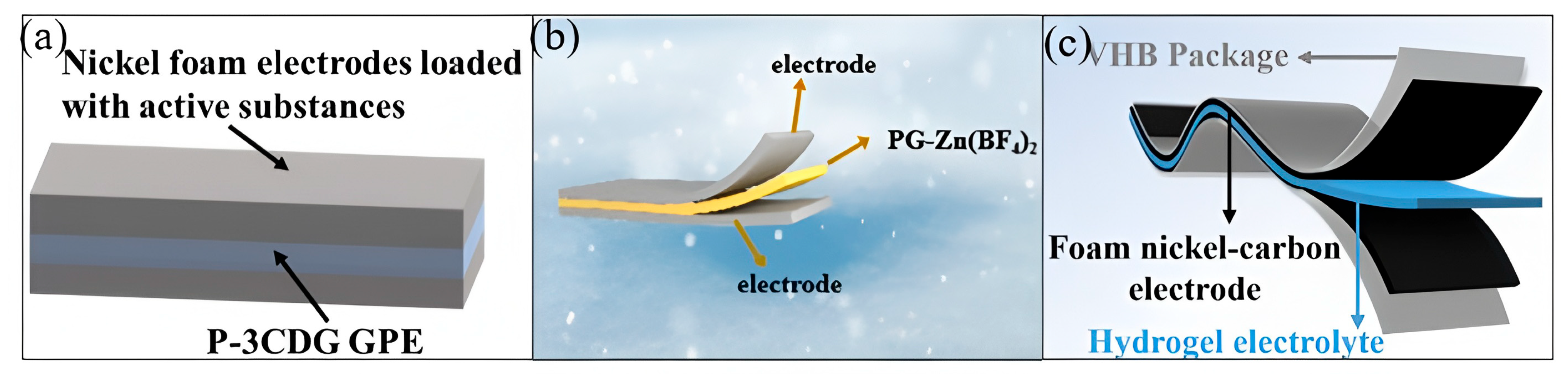

4.2. Flexible Energy Storage Devices

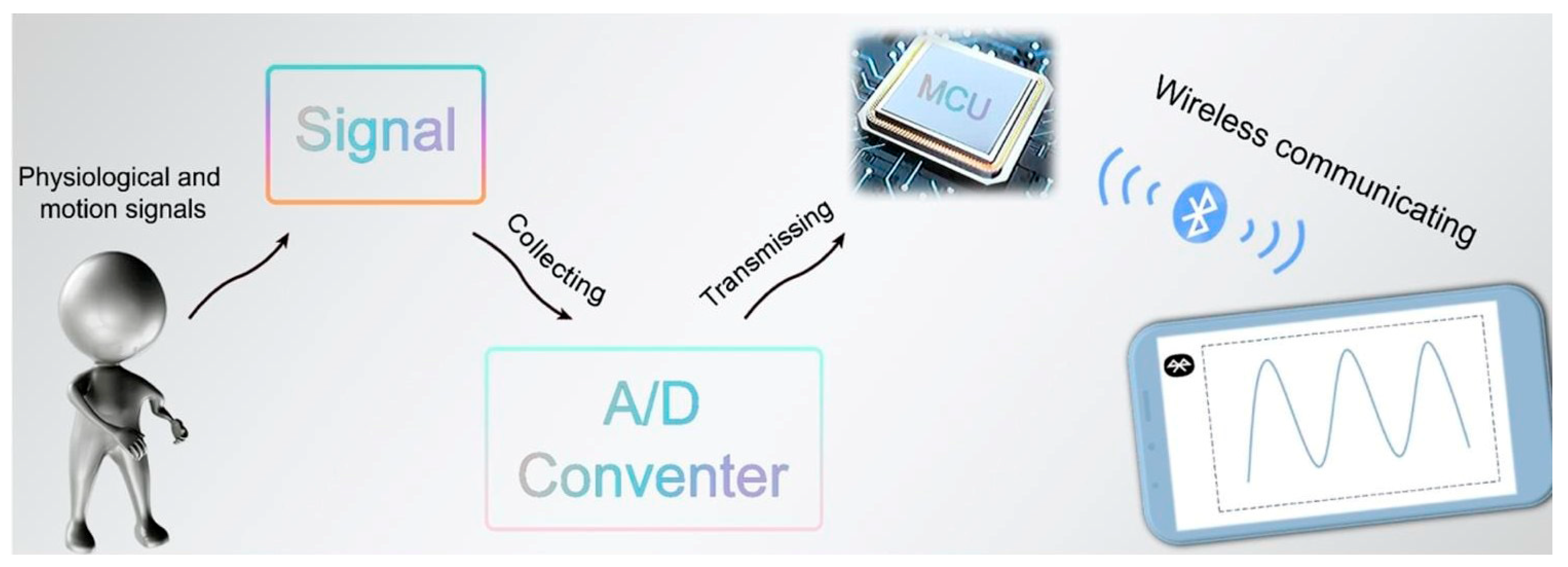

4.3. Health Monitoring Sensors

4.4. Physical Motion Sensors

| Performance Category | Specific Performance | References |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical properties | Tensile strength/stress | [16] |

| Self-recoverability | [22] | |

| Toughness | [24] | |

| Elongation at break/Tensile property/Ductility | [33] | |

| Fatigue resistance | [44] | |

| Compressive strength | [75] | |

| Physical properties | Adsorption performance | [15] |

| Adhesion | [20] | |

| Anti-swelling property | [26] | |

| Thermal responsiveness | [32] | |

| Humidity monitoring range | [38] | |

| Swelling behavior | [40] | |

| Electrical conductivity/Ionic conductivity | [43] | |

| Thermoelectric responsiveness | [45] | |

| Sensitivity | [53] | |

| Response time | [59] | |

| Low hysteresis energy | [59] | |

| Optical anisotropy | [60] | |

| Freeze resistance | [61] | |

| Stability | [66] | |

| Electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency | [74] | |

| Structural characteristics | Homogeneity | [15] |

| Interconnected Porous Structure | [21] | |

| Nanophase Separation | [34] | |

| Photonic Crystal Structure | [60] | |

| Conductive Pathways Formed by High-Aspect-Ratio Fillers | [73] | |

| Other characteristics | Environmental adaptability | [20] |

| pH responsiveness | [34] | |

| Biocompatibility | [39] |

5. Conclusions and Challenges

- (1)

- Weak anti-interference capability: Although high-sensitivity detection of biomarkers such as ATP and glucose can be achieved (e.g., the detection limit for ATP is 0.033 pM), the presence of interfering components like proteins and salts in complex bodily fluids (e.g., serum, sweat) can easily cause non-specific binding with the hydrogel network, leading to detection deviations. Existing antifouling designs (e.g., DNA modification) are tailored only for single biomarkers, making it difficult to adapt to simultaneous multi-biomarker detection.

- (2)

- Accelerated performance degradation due to environmental aging: When hydrogels are exposed to light and oxygen for extended periods, polymer chain degradation (e.g., PVA hydrolysis, MXene oxidation) is prone to occur, resulting in a 30–50% decline in mechanical properties and conductivity within 6 months. Moreover, in high-temperature (>40 °C) and high-humidity (relative humidity > 80%) environments, hydrogels are susceptible to “swelling-shrinking” cycles, gradually damaging the network structure and shortening their service life.

- (3)

- Complex preparation processes, high costs, and challenges in mass production: Most existing high-performance hydrogels rely on precisely controlled laboratory processes, such as “freezing-assisted metal complexation” and “insitu photopolymerization-freeze-thaw cycling.” Additionally, hydrogels from different batches fail to meet the “consistency” requirements of industrial production. The preparation costs of modified fillers (e.g., MXene, aminated CNTs) are high, and some processes depend on rare reagents (e.g., ionic liquids, specific enzymes). Furthermore, the storage of hydrogels requires sealed, low-temperature environments, further increasing warehousing and transportation costs.

6. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wibowo, A.F.; Sasongko, N.A.; Puspitasari, A.; Vo, T.T.; Entifar, S.A.N.; Sembiring, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Azizi, M.J.; Slamet, M.N.; Oh, J.; et al. Exceptionally low electrical hysteresis, soft, skin-mimicking gelatin-based conductive hydrogels for machine learning-assisted wireless wearable sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 526, 170741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Albiss, B. Fabrication of a highly sensitive pressure sensor based on Arabic gum polyacrylic acid nano-composite hydrogel enhanced with RGO/AgNPs. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 33628–33636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, J.; Bai, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Verma, Y.; Sharma, G.; Kumar, A.; Dhiman, P. Natural gums-derived hydrogels for adsorptive removal of heavy metals: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310, 143350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Chaturvedi, P.; Llamas-Garro, I.; Velázquez-González, J.S.; Dubey, R.; Mishra, S.K. Smart materials for flexible electronics and devices: Hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12984–13004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawon, M.T.; Chowdhury, I.F.; Paul, P.; Khan, M.S.; Haque, M.A.; Tang, Z.; Mondal, A.K. Lignin reinforced conductive hydrogels with antibacterial properties for flexible supercapacitor applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 332, 148722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Gupta, B.; Bano, S.; Singh, R. Temperature-driven soaking of hydrogels for high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators in wearable electronics. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 395, 117079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradinik, N.; Tarashi, S.; Nazockdast, H.; Garmabi, H. High-performance strain sensor based on stretchable and flexible nanocomposite double network hydrogel. Polymer 2025, 340, 129279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana; Ahmad, I.; Nimra, A.; Khan, M.; Shah, L.A.; Fu, J.; Yoo, H. Stretchable and self-adhesive ovalbumin-reinforced double-network polyacrylamide/gellan gum conductive hydrogel for wearable sensing human motion detection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 334, 149109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafloo, M.; Naji, L. Binary solvent-reinforced poly (vinyl alcohol)/sodium alginate double network hydrogel as a highly ion-conducting, resilient, and self-healing gel polymer electrolyte for flexible supercapacitors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zeng, L.Y.; Wang, X.C.; Chen, H.M.; Li, X.C.; Ni, H.L.; Yu, W.H.; Bai, Y.F.; Hu, P. Conductive hydrogel based on dual-network structure with high toughness, adhesion, self-healing and anti-freezing for flexible strain sensor. Next Mater. 2025, 6, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Huang, Y.X.; Yu, J.B.; Yang, X.; Luo, M.D.; Chen, X.P. A synergistic enhancement strategy for mechanical and conductive properties of hydrogels with dual ionically cross-linked κ-carrageenan/poly(sodium acrylate-co-acrylamide) network. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 346, 122638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.Y.; Wang, X.C.; Wen, Y.; Chen, H.M.; Ni, H.L.; Yu, W.H.; Bai, Y.F.; Zhao, K.Q.; Hu, P. Anti-freezing dual-network hydrogels with high-strength, self-adhesive and strain-sensitive for flexible sensors. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Dong, Y.; Liu, D. Supramolecular hydrogels: Mechanical strengthening with dynamics. Polymer 2020, 210, 122993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, H.; Katoh, K.I.; Sekine, N.; Sekine, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Ikeda-Fukazawa, T. Effects of hydrophilic groups of polymer on change in hydrogen-bonding structure of water in hydrogels during dehydration. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2024, 856, 141655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Wei, Q.; Wu, E.; Pu, H. Dual hydrogen-bond network-enhanced sensor of recycle SERS substrate using MXene/hydrogel for sensitive detection of malachite green residues in fish. Food Chem. 2025, 489, 145022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Chen, W.; Zou, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, Z.; Yu, N.; Huang, J.; Gan, L. Cellulose nanocrystal-modified hydrogel wearable sensor with self-healing function from dynamic bond and controllable dual hydrogen-bond crosslinking. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 363, 123760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, R.; Lv, L.; Wang, F.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yin, J.; Huang, R. Multiple hydrogen bond-crosslinked hydrogels engineered from natural microalgae framework and deep eutectic solvents for flexible freeze-resistant strain sensors. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 727, 138249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, L.A.; Zhao, B. Conductive supramolecular acrylate hydrogels enabled by quaternized chitosan ionic crosslinking for high-fidelity 3D printing. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 9, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, S.; Pitet, L.M. Ionic crosslinking strategies for poly(acrylamide)/alginate hybrid hydrogels. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 191, 105676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, H. Flexible, self-adhesive and eco-stable bioelectronics with dual-network phytic acid-based ionic hydrogel for biomechanical and physiological signal monitoring. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 701, 138720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, S.; Xu, W. Rapid fabrication of porous κ-carrageenan/cellulose nanofibrils-polydopamine composite hydrogels induced by ionic interaction for flexible electronic devices. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 198, 112438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, T. Strong and tough chitosan-based conductive hydrogels cross-linked by dual ionic networks for flexible strain sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 315, 144498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, M.; Hassan, N.; Roy, S.; Mondal, H.; Sanfui, M.H.; Rahaman, M.; Chattopadhyay, P.K.; Chang, M.; Singha, N.R. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of acrylic hydrogel-derivatives exploring structure-property relationship and coordinations/interactions with metal ions and dyes: A review. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1338, 142154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Ge, X.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xing, Z.; Wang, Z.X. Sturdy and conductive polyacrylamide/sodium alginate dual-network hydrogels improved via refreezing assisted metal complexation strategy for flexible sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Meng, J.; Zhennan, C.; Xueli, Y.; Xinran, W.; Ze, L.; Luo, S.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Qin, H. Preparation and properties of lignin-based dual network hydrogel and its application in sensing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 125913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Xie, T.; Gan, T.; Xu, X.; Tang, J.; Mo, L.; Liu, Z.; Qin, Z.; Gao, W.; et al. Construction of Dual Cross-Linked Conductive Hydrogels: Combining Toughness, Anti-Swelling, And Self-Healing Properties to Achieve Amphibious Multifunctional Sensing. Small 2025, 21, e09549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Vasilyev, G.; Vilensky, R.; Zussman, E. Controlling spatiotemporal mechanics of globular protein-polymer hydrogel via metal-coordination interactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marapureddy, S.G.; Thareja, P. Synergistic effect of chemical crosslinking and addition of graphene-oxide in Chitosan—Hydrogels, films, and drug delivery. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhad-Mokhtari, P.; Ghorbani, M.; Roshangar, L.; Rad, J.S. Chemical gelling of hydrogels-based biological macromolecules for tissue engineering: Photo- and enzymatic-crosslinking methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Maples, M.M.; Bryant, S.J. Cell encapsulation spatially alters crosslink density of poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels formed from free-radical polymerizations. Acta Biomater. 2020, 109, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yang, W.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Pan, R. Temperature/pH dual response hydrogel functionalized U-shaped optical fiber sensor for Pb2+ detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 429, 137297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, D.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, X.; Wu, J. High-Strength, Dual-Responsive Conductive Hydrogels With Ionic Crosslinking for Flexible Strain Sensors. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 63, 2834–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Wan, S.; Yang, S.; Zhao, X.; He, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, X.; Wen, Q.; Feng, Y.; Yu, G.; et al. Super stretchability, strong adhesion, flexible sensor based on Fe3+ dynamic coordination sodium alginate/polyacrylamide dual-network hydrogel. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 652, 129733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitiri, E.N.; Patrickios, C.S.; Voutouri, C.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Hoffmann, I.; Schweins, R.; Gradzielski, M. Double-networks based on pH-responsive, amphiphilic “core-first” star first polymer conetworks prepared by sequential RAFT polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardajee, G.R.; Ghadimkhani, R.; Jafarpour, F. A biocompatible double network hydrogel based on poly (acrylic acid) grafted onto sodium alginate for doxorubicin hydrochloride anticancer drug release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 128871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarhoum, S.; Ako, K.; Munialo, C.D.; Rharbi, Y. Helicity degree of carrageenan conformation determines the polysaccharide and water interactions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 314, 120952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, R.; Mohammadi, R. Preparation of pH-responsive magnetic nanocomposite hydrogels based on k-carrageenan/chitosan/silver nanoparticles: Antibacterial carrier for potential targeted anticancer drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Dual-Protein Network Hydrogel-Enabled Wireless Respiratory Sensing System. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 5366–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Chang, Y.; Ma, G.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Z. One-pot preparation of double network hydrogels via enzyme-mediated polymerization and post-self-assembly for wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 6195–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernencu, A.I.; Dinu, A.I.; Dinescu, S.; Trușcă, R.; Istodorescu, M.; Lungu, A.; Stancu, I.C.; Iovu, H. Inorganic/Biopolymers Hybrid Hydrogels Dual Cross-Linked for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Gels 2022, 8, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.; Kawai, M.; Mitsumata, T. Anomalous Magnetorheological Response for Carrageenan Magnetic Hydrogels Prepared by Natural Cooling. Gels 2023, 9, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, F.; Tahir, H.M.; Ali, S.; Ali, A.; Khan, H.A.; Muzamil, A.; Manzoor, H.H.; Qayyum, K.A. Biomolecules based hydrogels and their potential biomedical applications: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, N.; Kang, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Xue, Y.; Qiu, H. High-strength, conductive dual-network nanocomposite hydrogel for multi-substrate adhesion and enhanced wearable sensor performance. Polymer 2025, 334, 128743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yuan, W. Bidirectional temperature-responsive thermochromism and stretchable hydrogel sensor for human motion/health detection, visual signal transmission, and smart windows. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, P.; Lei, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Ye, J.; Ji, T.; Duan, W.; Yue, Y. Development of a two-mode hydrogel sensor with a thermal diffusion effect for intelligent sensing and temperature warning. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 55, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimiyan, N.; Gholami, M.; Sedghi, R. Preparation of degradable, biocompatible, conductive and multifunctional chitosan/thiol-functionalized graphene nanocomposite hydrogel via click chemistry for human motion sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buwalda, S.J. ‘Click’ hydrogels from renewable polysaccharide resources: Bioorthogonal chemistry for the preparation of alginate, cellulose and other plant-based networks with biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadim, H.; Asif, A.; Zeeshan, R.; Ilyas, T.; Ansari, A.A.; Ali, Z.; Yaqub, M. Design of modified chitosan/oxidized dextran based enhanced dual network adhesive hydrogels; An effective approach promoting wound healing. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 727, 138230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, M.; Jamali, R.; Kiyani, T.; Mohamadnia, Z.; Moradi, A.R. Characterization of Schiff base self-healing hydrogels by dynamic speckle pattern analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajimon, K.J.; Sreelakshmi, N.; Nair, D.S.R.; Begum, N.F.; Thomas, R. An in-depth study of the synthesis, electronic framework, and pharmacological profiling of 1-(anthracen-9-yl)-N-(4-nitrophenyl) methanimine: In vitro and in silico investigations on molecular docking, dynamics simulation, BSA/DNA binding and toxicity studies. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 8, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, F.; Zhong, M.; Liang, Y.; Wu, J. Skin-like dual-network gelatin/chitosan/emodin organohydrogel sensors mediated by Hofmeister effect and Schiff base reaction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, N.; Chen, X.; Lv, J. Polysaccharide-driven self-healing dual-network hydrogel via Schiff base for high-performance flexible sensing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 370, 124404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Ren, Z.; Gu, H. Totally dynamically cross-linked dual-network conductive hydrogel with superb and rapid self-healing ability for motion detection sensors. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, Z. High-strength dual-network hydrogels with chain-growth enhancement for multifunctional flexible sensors, triboelectric nanogenerators, and EMI shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yu, X.; Cao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Gu, X. Synergic enhancement of hydrogel upon multi-level hydrogen bonds via macromolecular design for dual-mode electronic skin. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, J.; Newton, M.A.A.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Xin, B. Multifunctional double network PVA-Borax/GO-cellulose nanofibrils hydrogel for wearable strain sensor. Polymer 2025, 337, 129027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, K.; Yan, H.; Gu, H.; Che, Y. High conductive, mechanical properties and temperature-sensitive alginate-based hydrogel enhanced with tunicate cellulose nanocrystals for wearable flexible sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 145032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, H.; Yu, J.; McSporran, E.; Khan, A.; Fan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ni, Y. Preparation of High-Strength Sustainable Lignocellulose Gels and Their Applications for Antiultraviolet Weathering and Dye Removal. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 2998–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Shah, L.A.; Rahman, T.U.; Yoo, H.M.; Ye, D.; Vacharasin, J. Cellulose nanocrystals boosted hydrophobic association in dual network polymer hydrogels as advanced flexible strain sensor for human motion detection. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 138, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, P.; Sun, L.; Sun, S.; Cao, X. Cellulose nanocrystals reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel with thermal, mechanical, and ionic responsive behavior. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Yue, D.; Bai, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, L.; Wei, D. Anti-freezing, self-healing and human sensors nanocomposite hydrogels based on functionalized cellulose nanocrystals and polydextrose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2026, 372, 124565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phanthong, P.; Reubroycharoen, P.; Hao, X.; Xu, G.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Nanocellulose: Extraction and application. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2018, 1, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y. Mesoporous MXene nanosheets/CNF composite aerogels for electromagnetic wave absorption and multifunctional response. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 157770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Mahapatra, S.N.; Yadav, R.; Mitra, S.; Samanta, A.; Kumar, A.; Lochab, B. 3D printed cellulose nanofiber-reinforced and iron-crosslinked double network hydrogel composites for tissue engineering applications: Mechanical properties and cellular viability. Bioprinting 2025, 46, e00392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, J.; An, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Jiao, D. Hydrophobic associations and cellulose nanofibers reinforced PVA/PAM multi-network conductive hydrogel with high sensitivity, fast response, and excellent mechanical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 368, 124225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Du, Z.; Li, T.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Cellulose nanofiber-reinforced dual-network multifunctional ion-conductive hydrogel with highly sensitive temperature and stress sensing properties for wearable flexible sensors. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 717, 136757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.; Punetha, V.D.; Bhatt, S.; Punetha, M. Carbon nanotube-based biocompatible polymer nanocomposites as an emerging tool for biomedical applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 196, 112257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Mohammed, B.S.; Woen, E.L. Modelling and optimizing the impact resistance of engineered cementitious composites with Multiwalled carbon nanotubes using response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UrRehman, T.; Khan, S.A.; Shah, L.A.; Fu, J. Gum arabic-CNT reinforced hydrogels: Dual-function materials for strain sensing and energy storage in next-generation supercapacitors. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.S.; Bhat, A.S.; Mehandi, R.; Abugu, H.O.; Onwujiogu, V.C.; Orjiocha, S.I.; Chinonso, E.F. Advances in sensing technologies using functional carbon nanotube-hydrogel nanocomposites. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 175, 114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Alsubaie, A.S.; El-Bahy, S.M.; Qiu, H.; Jiang, D.; Wu, Z.; Ren, J.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; et al. Carbon nanotube reinforced ionic liquid dual network conductive hydrogels: Leveraging the potential of biomacromolecule sodium alginate for flexible strain sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, N.; Zhang, L.; He, Q.; Ren, L.; Song, W. Dual-network conductive hydrogels based on carboxymethylcellulose/aminated carbon nanotube reinforcement: Monitoring human micro-expressions and signal changes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Cai, L.; Zhu, G.; Chen, L.; Xie, X.; Guo, J. Nanocellulose and multi-walled carbon nanotubes reinforced polyacrylamide/sodium alginate conductive hydrogel as flexible sensor. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 677, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Qian, K.; Miao, M.; Ye, J.; Feng, X. Liquid metal integrated cellulose nanocrystal/polyacrylic acid dual-network hydrogel towards high-performance wearable sensing and electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 251, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, H.; Liu, B.; Shi, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C. Flexible and self-healing tannic acid-Fe3O4@MXene-composited dual network hydrogel multifunctional strain sensor. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 702, 135028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Su, F.; Fan, L.; Mu, Z.; Wang, H.; He, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yao, D.; Zheng, Y. Robust and stretchable Ti3C2Tx MXene/PEI conductive composite dual-network hydrogels for ultrasensitive strain sensing. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 176, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Wang, R. Sound-bioinspired dual-conductive hydrogel sensors for high sensitivity and environmental weatherability. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2025, 44, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Ta, Q.T.H.; Nguyen, T.K.O.; Nguyen, T.T.D.; Vo, V.G. Role of Body-Fluid Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Kumar, S.; Koh, J. Innovations in wearable biosensors: A pathway to 24/7 personalized healthcare. Measurement 2025, 254, 117938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiraman, S.; Sha, R.; Mani, N.K. Recent advancements in Point-of-Care Detection of Contaminants and Biomarkers in Human Breast Milk: A comprehensive review. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2025, 9, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qiao, X.; Wei, Z.; Yang, Q.; Xu, S.; Li, C.C.; Luo, X. An antifouling electrochemical biosensor based on chitosan and DNA dual-network hydrogel for ATP quantification in complex biofluids. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 424, 136937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Zhu, J. Interfacing hydrogel microneedle patch for diagnosis. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 55, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arwani, R.T.; Tan, S.C.L.; Sundarapandi, A.; Goh, W.P.; Liu, Y.; Leong, F.Y.; Yang, W.; Zheng, X.T.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, C.; et al. Stretchable ionic–electronic bilayer hydrogel electronics enable in situ detection of solid-state epidermal biomarkers. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Gao, H.; Li, X.; Xu, D.; Xu, L. Boric acid-functionalized PANI-ABA/PA hydrogel-based flexible pH sensor for real-time sweat monitoring. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1362, 344188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yu, W.; Xiong, H.; Xia, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y. Wearable Double Network Plasmonic Hydrogel for SERS Detection of Urea and Uric Acid in Sweat. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 6123–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, S.; Patil, O.A.; Park, S.Y.; Choi, S.J.; Pawar, O.; Joe, D.J.; Lim, S.; Lee, H.E. Wearable sweat glucose monitoring patches enabled by double network hydrogel-MoS2/PEDOT: PSS nanocomposite. Microchem. J. 2025, 215, 114309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Liang, S.; Tian, S.; Cao, Y.; Cui, N.; Yang, H. A multifunctional flexible sensor with dual-conductive networks for monitoring human motion signals and sweat pH/Lactic acid. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 265, 111130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, K.; Saha, T.; Ding, S.; Sandhu, S.S.; Chang, A.Y.; Wang, J. Hybrid multimodal wearable sensors for comprehensive health monitoring. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.D.; Gupta, P.; Kumari, V.; Rana, I.; Jindal, D.; Sagar, N.; Singh, J.; Dhand, C. Wearable biosensors in modern healthcare: Emerging trends and practical applications. Talanta Open 2025, 12, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasankumar, T.; Suntharam, N.M.; Manoharan, K.; Kumar, S.S.A.; Gerard, O.; Saroj, A.L.; Bashir, S.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K. Carbon nanofiber/conducting polymer hybrids for flexible and wearable energy storage devices. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 46, e01757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Wong, K.K.L.; Javed, M.S.; Zhang, W.J.C. Flexible MXene–Hydrogel Mechatronics for Next-Generation Energy Storage Applications: A Review. Energy Storage Mater. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, W.; He, X.; Zheng, X.; Wang, K.; Shi, J.; Song, Z.; Liu, B.; Zeng, X.; Zuo, M. Rational design of anti-freezing dual-network hydrogels with superior mechanical and self-healing properties for advanced flexible electronics. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, J.; Ignaszak, A. Flexible Electrode Based on MWCNT Embedded in a Cross-Linked Acrylamide/Alginate Blend: Conductivity vs. Stretching. Polymers 2020, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, R. Hydrogel Electrolyte Enabled High-Performance Flexible Aqueous Zinc Ion Energy Storage Systems toward Wearable Electronics. Small 2023, 19, 2303949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Tang, W.; Han, D.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Huang, H.; Sun, G.; Zhang, L.; Lai, L. Highly stretchable dual network hydrogel electrolytes for supercapacitors at −80 °C. J. Power Sources 2025, 641, 236856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Chen, W.; Ge, X.; Li, S.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.X. Stretchable, self-adhesion and durable polyacrylamide/polyvinylalcohol dual-network hydrogel for flexible supercapacitor and wearable sensor. J. Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumma, S.B.; Mamun, A.; Ghasemzadeh, H. AI-powered wearable sensors for health monitoring and clinical decision making. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 36, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Ke, T.; Liu, W.; Ren, Z.; Zhao, L.; Gu, H. Tough, Repeatedly Adhesive, Cyclic Compression-Stable, and Conductive Dual-Network Hydrogel Sensors for Human Health Monitoring. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 18373–18383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yao, Y.; Chen, D. Wearable strain sensor based on double network PVA/SA/CNT hydrogel for reliable electrocardiography and motion monitoring. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 396, 117196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Jiao, M.; Yang, M.; Qiao, Y.; He, Q.; Fei, T.; Yang, Z. Dual-Mode, Self-Powered, and Flexible Humidity Sensor Based on Double-Network Hydrogel with Multifunctional Applications. Small Methods 2025, 9, e00771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Bosch, S.; Incel, O.D.; Scholten, H.; Havinga, P.J.M. Fusion of Smartphone Motion Sensors for Physical Activity Recognition. Sensors 2014, 14, 10146–10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Cui, T.; Zhu, J.; Gui, Z. Advancing high-performance tailored dual-crosslinking network organo-hydrogel flexible device for wireless wearable sensing. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 653, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, C.; Guo, M.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xiang, D.; Li, H.; Wang, L. Underwater sensors based on dual dynamically crosslinked hydrogels with excellent anti-swelling and adhesive properties. Polymer 2024, 305, 127160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, F.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wen, X.; Song, H. Anisotropic nanocomposite double network anti-freezing hydrogels with superior conductivity, high stretchability, and excellent resilience for wearable sensors. Compos. Commun. 2025, 59, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, L.; Sher, M.; Khan, M.; Rehman, T.U.; Shah, L.A.; Yoo, H.M. Dually-crosslinked ionic conductive hydrogels reinforced through biopolymer gellan gum for flexible sensors to monitor human activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Jia, J.; Sun, C.; Xu, L.; Li, X. Preparation of Dual-Network Hydrogels and Their Application in Flexible Electronics. Gels 2025, 11, 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120958

Yang Y, Jia J, Sun C, Xu L, Li X. Preparation of Dual-Network Hydrogels and Their Application in Flexible Electronics. Gels. 2025; 11(12):958. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120958

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yang, Jingna Jia, Chao Sun, Longbin Xu, and Xinyu Li. 2025. "Preparation of Dual-Network Hydrogels and Their Application in Flexible Electronics" Gels 11, no. 12: 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120958

APA StyleYang, Y., Jia, J., Sun, C., Xu, L., & Li, X. (2025). Preparation of Dual-Network Hydrogels and Their Application in Flexible Electronics. Gels, 11(12), 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120958