Multifunctional Metal Composite Hydrogels for Diabetic Wound Therapy

Abstract

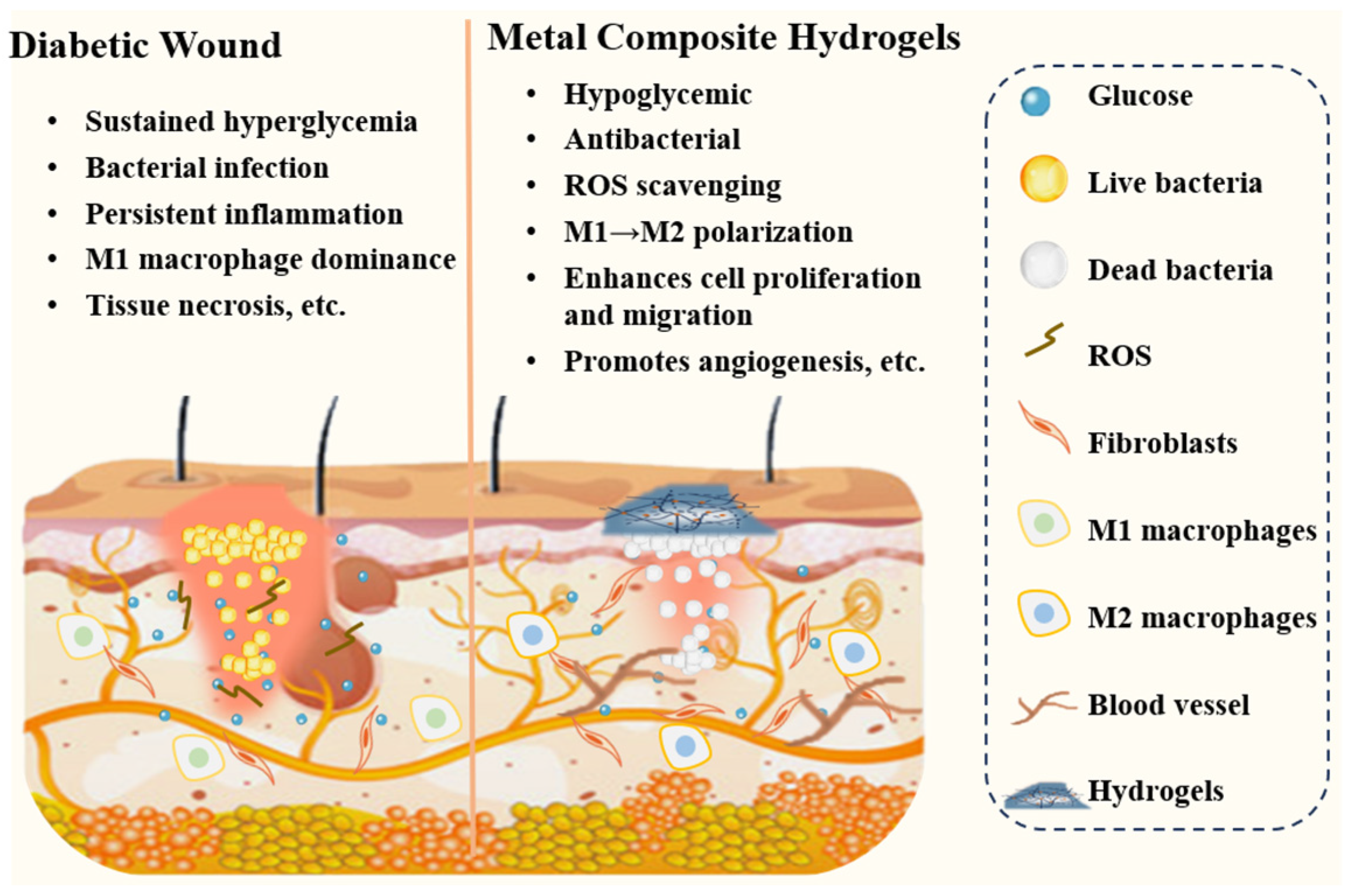

1. Introduction

2. Preparation of Metal Composite Hydrogels

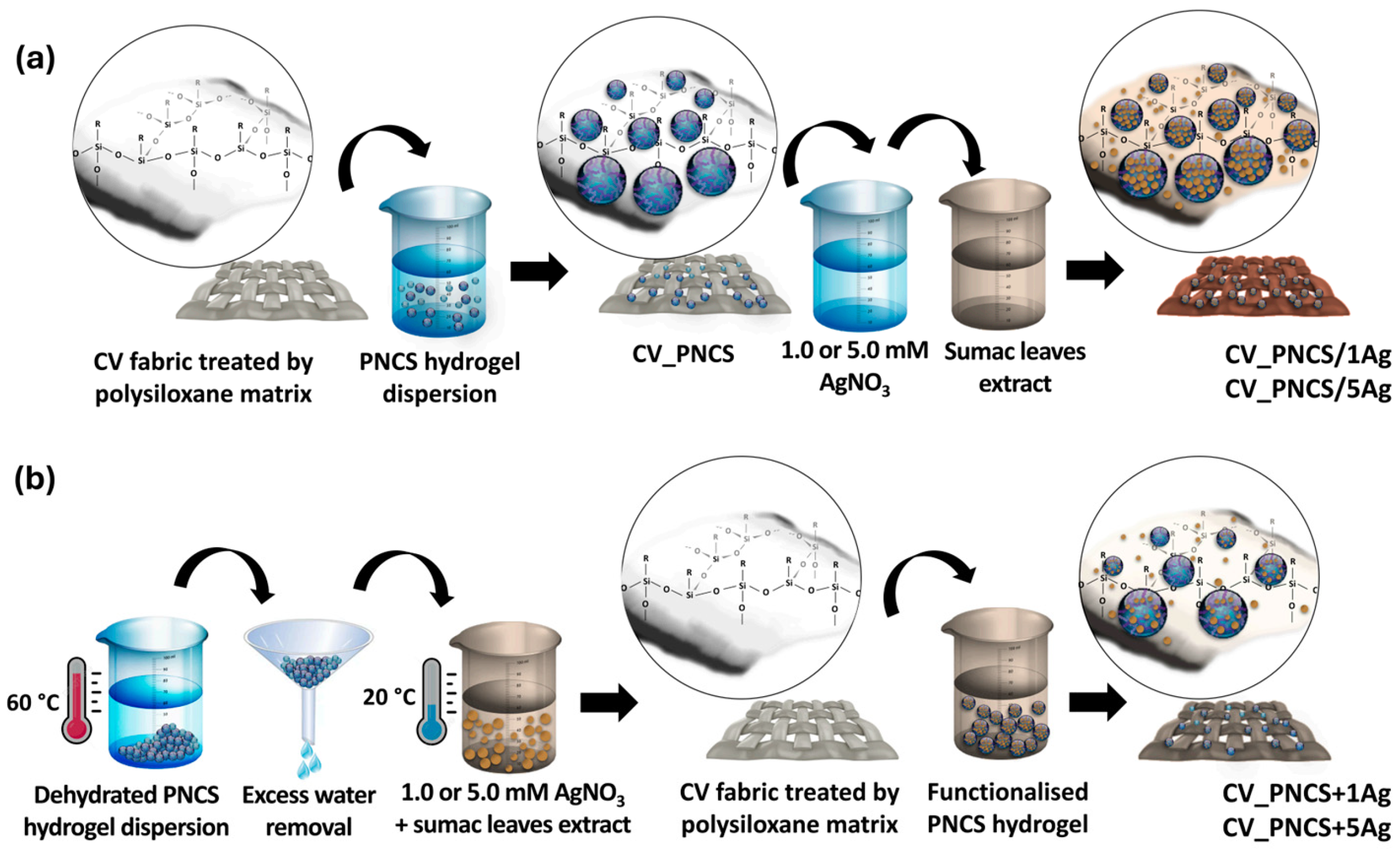

2.1. Physically Doped Composite Hydrogels

2.2. Chemically Doped Composite Hydrogels

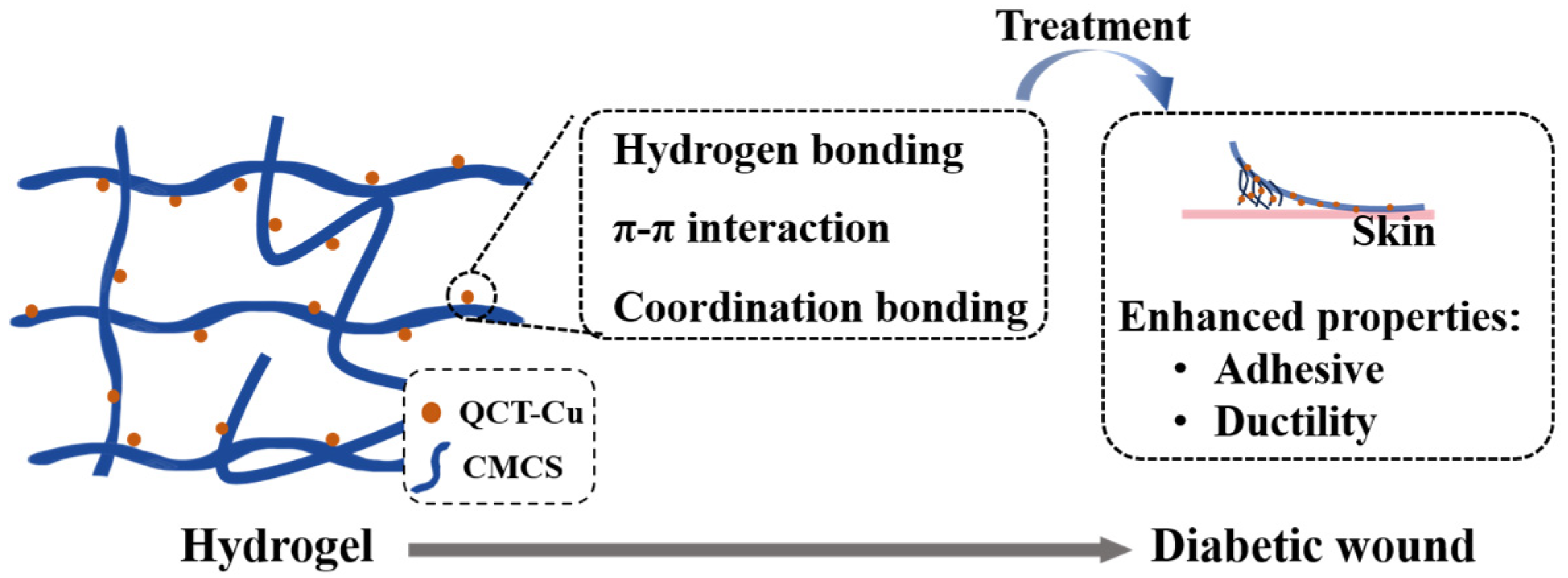

2.2.1. Doping Based on Coordination Interactions

2.2.2. Doping Based on Covalent Integration

2.2.3. Doping via In Situ Reduction and Chelation

2.3. Hybrid-Doped Composite Hydrogels

3. Use of Metal Composite Hydrogels in Diabetic Wound Therapy

3.1. Silver-Based Composite Hydrogels

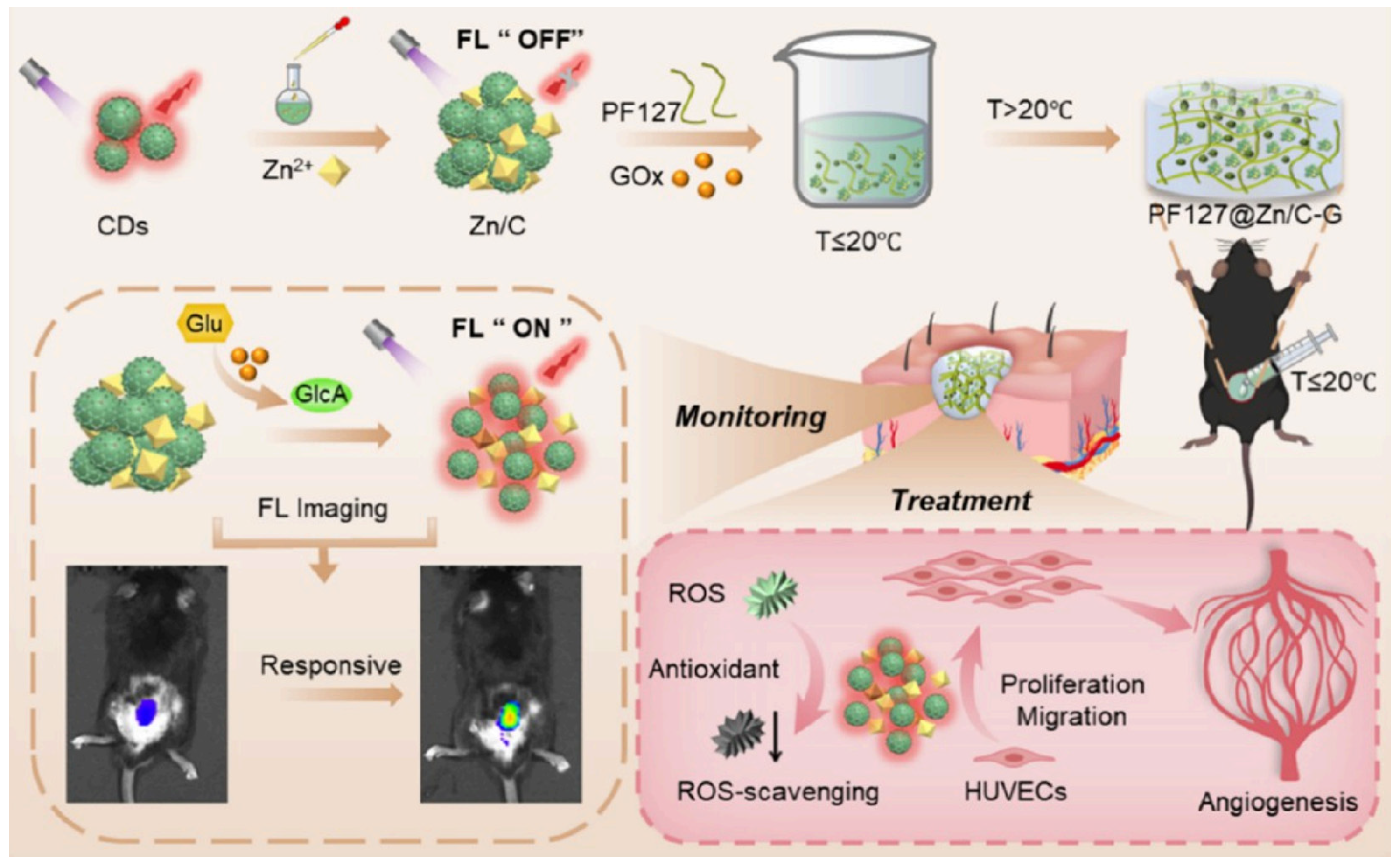

3.2. Zinc-Based Composite Hydrogels

3.3. Copper-Based Composite Hydrogels

3.4. Iron-Based Composite Hydrogels

3.5. Other Metal Composite Hydrogels

4. Biosafety Evaluation

4.1. In Vitro Evaluation Methods

4.2. In Vivo Evaluation Methods

5. Conclusions, Challenges, and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, J.F.; Chang, T.J.; Yeh, M.L.; Shen, F.C.; Tai, C.M.; Chen, J.F.; Huang, Y.H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Cheng, P.N.; Lin, C.L.; et al. Clinical care guidance in patients with diabetes and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A joint consensus. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Jun, D.W.; Toyoda, H.; Hsu, Y.C.; Trinh, H.; Nozaki, A.; Ishikawa, T.; Watanabe, T.; Uojima, H.; Huang, D.Q.; et al. Impacts of metabolic syndrome diseases on long-term outcomes of chronic hepatitis B patients treated with nucleos(t)ide analogues. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnum-Hansen, H.; Davidsen, M.; Andersen, I. Impact of the association between education and obesity on diabetes-free life expectancy. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.M.S.; Carlsson, B.; Jacobson, P.; Andersson-Assarsson, J.C.; Karlsson, C.; Kristensson, F.M.; Ahlin, S.; Näslund, I.; Karason, K.; Svensson, P.A.; et al. Association between delay in diabetes development and mortality in people with obesity: Up to 33 years follow-up of the prospective swedish obese subjects study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fu, Y.Q.; Tan, X.; Wang, N.J.; Qi, L.; Lu, Y.L. Assessing the impact of type 2 diabetes on mortality and life expectancy according to the number of risk factor targets achieved: An observational study. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Castellanos, N.; Cuartas-Gómez, E.; Vargas-Ceballos, O. Functionalized collagen/poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate interpenetrating network hydrogel enhances beta pancreatic cell sustenance. Gels 2023, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmagadda, S.M.; Suryanarayana, G.; Kumar, G.B.; Anudeep, G.; Sai, G.V. A comprehensive survey on diabetes Type-2 (T2D) forecast using machine learning. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2024, 31, 2905–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.; Czaja, K. Can circadian eating pattern adjustments reduce risk or prevent development of T2D? Nutrients 2023, 15, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendland, D.M.; Altenburger, E.A.; Swen, S.B.; Haan, J.D. Diabetic foot ulcer beyond wound closure: Clinical practice guideline. Phys. Ther. 2025, 105, pzae171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Jahan, N.; Khatoon, R.; Ansari, F.M.; Ahmad, S. The diabetic foot ulcer: Biofilm, antimicrobial resistance, and amputation. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2025, 45, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mashayamombe, M.; Walsh, T.P.; Kuang, B.K.P.; Pena, G.N.; Vreugde, S.; Cooksley, C.; Carda-Diéguez, M.; Mira, A.; Jesudason, D.; et al. The bacteriology of diabetic foot ulcers and infections and incidence of Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants. J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 72, 001716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chary, P.S.; Urati, A.; Shaikh, S.; Yadav, R.; Bhavana, V.; Rajana, N.; Mehra, N.K. Nanotechnology-enabled approaches for combating diabetic foot ulcer. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 105, 106593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Thomas, D.W. High Glucose alters endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores in T lymphocytes revealing potential novel therapeutic targets for diabetic-induced immune dysfunction. Physiology 2024, 39, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.T.; Yu, Y.F.; Kang, H.F.; Dong, X.Z.; Dai, H.L.; Yu, A.X. Dual-layer microneedles with NO/O2 releasing for diabetic wound healing via neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and immune modulation. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 46, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, W.Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.N.; Feng, S.N.; Mei, Z.Q. How effective are nano-based dressings in diabetic wound healing? A comprehensive review of literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 2097–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, Y.J.; Zhao, L. pH-responsive calcium alginate hydrogel laden with protamine nanoparticles and hyaluronan oligosaccharide promotes diabetic wound healing by enhancing angiogenesis and antibacterial activity. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.J.; Zheng, W.F.; Yu, Y.M.; Liu, R.F.; Gong, Y.H.; Huang, M.T.; Fan, M.D.; Wang, L. Dextran-functionalized cerium oxide nanoparticles for treating diabetic wound infections by synergy between antibacterial activity and immune modulation. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 33, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Qu, S.; Ouyang, Q.H.; Qin, F.; Guo, J.M.; Qin, M.; Zhang, J.J. A multifunctional composite nanoparticle with antibacterial activities, anti-inflammatory, and angiogenesis for diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; He, W.J.; Mu, X.R.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Nie, X.Q. Macrophage polarization in diabetic wound healing. Burn. Trauma 2022, 10, tkac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accipe, L.; Abadie, A.; Neviere, R.; Bercion, S. Antioxidant activities of natural compounds from caribbean plants to enhance diabetic wound healing. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebakumar, M.; Pachaiyappan, M.; Kamini, N.R.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Ayyadurai, N. Engineered spider silk in core-shell multifunctional fibrous mat for accelerated chronic diabetic wound healing via macrophage polarization. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 6017–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tan, X.Y.; Xue, Y.; Xiao, C.; Yue, K.J.; Lin, K.B.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Q.H.; Zhang, J.L. Smart diabetic foot ulcer scoring system. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aybar, J.N.A.; Mayor, S.O.; Olea, L.; Garcia, J.J.; Nisoria, S.; Kolling, Y.; Melian, C.; Rachid, M.; Dimani, R.T.; Werenitzky, C.; et al. Topical administration of lactiplantibacillus plantarum accelerates the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers through modifications of infection, angiogenesis, macrophage phenotype and neutrophil response. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, S.M.; Wolfe, G.I.; Vernino, S.; Raskin, P.; Hynan, L.S.; Wyne, K.; Fulmer, R.; Pandian, G.; Sharma, S.K.; Mohanty, A.J.; et al. Effect of lower extremity nerve decompression in patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Ann. Surg. 2024, 280, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.W.; Wang, L.H.; Liu, Z.M.; Luo, Y.M.; Kang, Z.C.; Che, X. Astragaloside/PVP/PLA nanofiber functional dressing prepared by coaxial electrostatic spinning technology for promoting diabetic wound healing. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 210, 112950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.C.; Wang, J.Y.; Huang, G.F.; Dai, J.Z. Silver dressings for treating diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Tissue Viability 2025, 34, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Liu, B.; Pi, Y.Z.; Hu, L.; Yuan, Y.L.; Luo, J.; Tao, Y.X.; Li, P.; Lu, S.; Song, W. Risk factors for diabetic foot ulcers mortality and novel negative pressure combined with platelet-rich plasma therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1051299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic, P.; Savic, M.; Bolevich, S.; Bolevich, S.; Orlova, A.; Mikhaleva, A.; Kartashova, A.; Yavlieva, K.; Turnic, T.N.; Pindovic, B.; et al. Examining the effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on the cardiovascular system and oxidative stress in insulin-treated and non-treated diabetic rats. Animals 2023, 13, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwland, A.J.; Waibel, F.W.A.; Flury, A.; Lisy, M.; Berli, M.C.; Lipsky, B.A.; Uçkay, I.; Schöni, M. Initial antibiotic therapy for postoperative moderate or severe diabetic foot infections: Broad versus narrow spectrum, empirical versus targeted. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 3290–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, Y.F.; Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.H.; Xu, X.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Cun, D.M.; Bera, H.; Yang, M.S. High molecular weight laminarin/AgNPs-impregnated PVA based in situ hydrogels accelerated diabetic wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 367, 123991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.X.; Gao, B.B.; Chen, Z.H.; Mei, X.F. An NIR-triggered Au nanocage used for photo-thermo therapy of chronic wound in diabetic rats through bacterial membrane destruction and skin cell mitochondrial protection. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 779944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.T.; Wang, L.T.; Lu, Z.F.; Yang, X.Y.; Lu, Y.X.; Wang, Z.X.; Wu, Q.X.; Qin, X.F. An injectable conductive multifunctional hydrogel dressing with synergistic antimicrobial, ROS scavenging, and electroactive effects for the combined treatment of chronic diabetic wounds. Biomater. Adv. 2026, 179, 214498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Z.M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.R.; Zhang, T.; Bei, H.P.; Feng, Z.X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, K.; Hsu, Y.Y.; et al. Triple-molded, reinforced arrowhead microneedle patch of dual human-derived matrix for integrated management of diabetic wounds. Biomaterials 2026, 324, 123520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.L.; Liang, X.Y.; Shen, Z.Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, G.; Yu, B.R.; Li, Y.; Xu, F.J. Glucose-responsive hydrogel with adaptive insulin release to modulate hyperglycemic microenvironment and promote wound healing. Biomaterials 2026, 326, 123641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.C.; Geng, X.R.; Zhang, Y.F.; Shi, Y.J.; Zhao, L. Microenvironmental pH modulating oxygen self-boosting microalgal prodrug carboxymethyl chitosan/hyaluronic acid/puerarin hydrogel for accelerating wound healing in diabetic rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.Y.; Mao, L.C.; Chen, X.W.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.S.; Jiang, N.; Yang, K.D.; Duan, S.; Gan, Z.H.; et al. A heterogeneous hydrogel patch with mechanical activity and bioactivity for chronic diabetic wound healing. Biomaterials 2026, 324, 123531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, W.M.; El-Habashy, S.E.; El-Hosseiny, L.S.; Essawy, M.M.; Eltaher, H.M.; El-Khordagui, L.K. Bioinspired 3D-printed scaffold embedding DDAB-nano ZnO/nanofibrous microspheres for regenerative diabetic wound healing. Biofabrication 2024, 16, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Shahriar, S.M.S.; Su, Y.J.; Hayati, F.; Andrabi, S.M.; Xiao, Y.Z.; Busquets, M.E.; Sharma, N.S.; Xie, J.W. Three-dimensional bioprinting of biphasic nanobioink for enhanced diabetic wound healing. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 21411–21425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C.Y.; Qi, W.; Wang, M.F. A hydrogen-bonded biohybrid organic framework hydrogel for enhanced diabetic wound therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakheel, F.M.; Mohsen, D.; El Sayed, M.M.; Fagir, M.H.; El Dein, D.K. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles loaded in polysaccharide hydrogel applied to chronic wound healing in mice models. Gels 2023, 9, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.L.; Lan, Y.L.; Chen, J.; Xiang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Jiang, L.T.; Dong, Y.J.; Li, J.X.; Liao, Z.Y.; Li, Z.P.; et al. An endogenous adenosine triphosphate-activated hydrogel prodrug system for healing multidrug-resistant bacteria infected diabetic foot ulcers. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2500688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Tan, Y.Q.; Leng, S.L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, L.Y.; Wang, C.F. Cupric-polymeric nanoreactors integrate into copper metabolism to promote chronic diabetic wounds healing. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 26, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wu, D.G.; Su, Z.W.; Guo, J.Y.; Cui, L.Y.; Su, H.; Chen, Y.; Yu, B. Zinc-induced photocrosslinked konjac glucomannan/glycyrrhizic acid hydrogel promotes skin wound healing in diabetic mice through immune regulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.L.; Zhao, B.J.; Li, M.C.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.Y.; Li, Q.T.; Gao, H.C.; Feng, Q.; Cao, X.D. Microenvironment responsive nanocomposite hydrogel with NIR photothermal therapy, vascularization and anti-inflammation for diabetic infected wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 26, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.A.; Xiang, F.; Bu, P.Z.; Lv, Q.Q.; Liu, X.Z.; Zhou, B.K.; Tan, M.J.; Jiang, X.; Cheng, X.; Serda, M.; et al. A hydrogel crosslinked with mixed-valence copper nanoclusters for diabetic wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2025, 200, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.X.; Hu, Y.; Xu, Q.Y.; Zhou, Y.N.; Xu, Y.J. An injectable triple-responsive chitosan-based hydrogel encapsulating QCT-Cu self-assembled nanoparticles accelerating diabetic wound healing via remodeling the local microenvironment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 363, 123706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Q.; Sun, Y.F.; Jiang, G.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Wang, R.; Nie, L.; Shavandi, A.; Yunusov, K.E.; Aharodnikau, U.E.; Solomevich, S.O. Porcupine-inspired microneedles coupled with an adhesive back patching as dressing for accelerating diabetic wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2023, 160, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.K.; Wei, S.M.; Su, S.Q.; Tang, Z.S.; Wang, Y.H. A multifunctional hydrogel fabricated by direct self-assembly of natural herbal small molecule mangiferin for treating diabetic wounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 24221–24234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.K.; Zhou, P.R.; Li, S.C.; Zhang, X.C.; Xia, Z.X.; Rao, Z.H.; Ma, X.M.; Hu, Y.J.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, J.L.; et al. From hemostasis to angiogenesis: A self-healing hydrogel loaded with copper sulfide-based nanoenzyme for whole-process management of diabetic wounds. Biomater. Res. 2025, 29, 0208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, T.H.; Chen, S.H.; Du, J.; Luo, J.J.; Yan, X.Y. A dZnONPs enhanced hybrid injectable photocrosslinked hydrogel for infected wounds treatment. Gels 2022, 8, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Hu, F.F.; Chai, Z.H.; Zheng, C.Y.; Zhang, W.H.; Pu, K.; Yang, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.N.; Ramrkrishna, S.; Wu, X.L.; et al. Multifunctional hydrogel with mild photothermal properties enhances diabetic wound repair by targeting MRSA energy metabolism. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.Q.; Zhu, J.Z.; Hao, Z.K.; Tang, L.T.; Sun, J.; Sun, W.R.; Hu, J.X.; Wang, P.Y.; Basmadji, N.P.; Pedraz, J.L.; et al. Renewable electroconductive hydrogels for accelerated diabetic wound healing and motion monitoring. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 3566–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.M.; Ge, G.R.; Li, W.H.; Dong, J.L.; Hu, X.L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Bai, J.X.; Zhang, W.W.; Su, Z.; et al. Sr-MOF-based hydrogel promotes diabetic tissue regeneration through simultaneous antimicrobial and antiinflammatory properties. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 32, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B.; Wang, C.F.; Wu, S.L.; Yan, D.N.; Huang, C.H.; Mao, C.Y.; Zheng, Y.F.; Liu, H.P.; Jin, L.G.; Zhu, S.L.; et al. Accelerating interface NIR-induced charge transfer through Cu and black phosphorus modifying G-C3N4 for rapid healing of Staphylococcus aureus infected diabetic ulcer wounds. Small 2025, 21, 2500378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Qiu, J.J.; Chen, S.H.; Nie, X.S.; Zhao, L.L.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.R.; Liu, X.Y. Zn ion-incorporated injected hydrogels with reactive oxygen species and glucose scavenging capacity for diabetic wound healing. Burn. Trauma 2025, 13, tkae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Lu, L.; Chen, J.Y.; Weng, Y.J. Biomimetic hydrogel scaffolds with copper peptide-functionalized RADA16 nanofiber improve wound healing in diabetes. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, 2200019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Ji, H.B.; Min, C.H.; Kim, C.R.; Han, J.H.; Kim, S.N.; Yoon, S.B.; Kwon, E.J.; Lee, C.L.; Choy, Y.B. Fe-porphyrin cross-linked hydrogel for reactive oxygen species scavenging and oxygen generation in diabetic wounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 14583–14594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Y.; Wen, M.Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, L.B.; Xue, Y.M.; Shang, L. Marine-derived nanozyme-crosslinked self-adaptive hydrogels for programmed regulating the regeneration process. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 202405257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.R.; Li, W.J.; Qu, J.Q.; Wang, Q.; Che, T.J.; Yan, L.B.; Cui, H.L.; Liu, D.T.; Qin, S. Modified fish-skin-collagen-based hydrogels with antioxidant and antibacterial functions for diabetic wound healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2501456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, N.; Ahmed, R.; Tariq, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Masoud, M.S.; Ali, I.; Asghar, R.; Andleeb, A.; Hasan, A. Silver nanoparticle impregnated chitosan-PEG hydrogel enhances wound healing in diabetes induced rabbits. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 559, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, S.; Hussain, Z.; Ullah, I.; Wang, L.; Mehmood, S.; Liu, Y.S.; Mansoorianfar, M.; Liu, X.Z.; Ma, F.S.; Pei, R.J. Mussel bioinspired, silver-coated and insulin-loaded mesoporous polydopamine nanoparticles reinforced hyaluronate-based fibrous hydrogel for potential diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 247, 125738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majie, A.; Saha, R.; Sarkar, A.; Bhowmik, R.; Karmakar, S.; Sharma, V.; Deokar, K.; Haque, A.U.; Tripathy, S.S.; Sarkar, B. A novel chitosan-PEG hydrogel embedded with in situ silver nanoparticles of Clerodendrum glandulosum Lindl. extract: Evaluation of its in vivo diabetic wound healing properties using an image-guided machine learning model. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 4242–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.K.; Singh, A.; Singh, D.; Shraogi, N.; Verma, R.; Saji, J.; Jagdale, P.; Ghosh, D.; Patnaik, S. Biopolymeric composite hydrogel loaded with silver NPs and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) effectively manages ROS for rapid wound healing in type II diabetic wounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.N.; Zheng, Y.J.; Jin, J.; Wu, X.; Xu, K.J.; Dai, M.L.; Niu, Q.; Zheng, H.; He, X.J.; Shen, J.L. Immunoregulation in diabetic wound repair with a photoenhanced glycyrrhizic acid hydrogel scaffold. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Liu, D.Q.; Ren, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.H.; Wang, T.X.; Guan, Z.W.; Yu, K.; Chu, L.L.; et al. Double crosslinked hydrogels loaded with zinc-ellagic acid metal-organic frameworks combined with a mild heat stimulation promotes diabetic wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.S.; Shen, J.; Du, F.K.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.X.; Wu, X.; Chen, M.J.; et al. Bilayer hydrogel with a protective film and a regenerative hydrogel for effective diabetic wound treatment. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 5036–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.H.; Li, Z.L.; Wang, J.X.; Li, T.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Duan, X.L.; Guo, B.L. Photothermal antibacterial antioxidant conductive self-healing hydrogel with nitric oxide release accelerates diabetic wound healing. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2023, 266, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, Z.H.; He, Y.J.; Sun, Y.; Peng, Q.; Zhao, M.; Huang, X.J.; Lei, L.; Gu, H.; Gou, K.J.; et al. Polydopamine nanoparticle-integrated smart bletilla striata polysaccharide hydrogel: Photothermal-triggered CO2 release for diabetic wound microenvironment modulation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 8873–8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.H.; Pu, Y.J.; Ren, Y.H.; Kong, W.H.; Xu, L.L.; Zhang, W.J.; Shi, T.Q.; Ma, J.P.; Li, S.; Tan, X.Y.; et al. Enzyme-regulated NO programmed to release from hydrogel-forming microneedles with endogenous/photodynamic synergistic antibacterial for diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 226, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, S.Y.; Zhao, W.F.; Zhao, C.S. A rapid-triggered approach towards antibacterial hydrogel wound dressing with synergic photothermal and sterilization profiles. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 138, 212873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.H.; Wang, P.; Ma, Z.; Peng, L.; Guo, C.Y.; Fu, Y.Q.; Ding, L.Z. Lupeol-loaded chitosan-Ag plus nanoparticle/sericin hydrogel accelerates wound healing and effectively inhibits bacterial infection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 243, 125310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazar, D.; Stular, D.; Jerman, I.; Simoncic, B.; Tomsic, B. Embedment of biosynthesised silver nanoparticles in polyNIPAAm/chitosan hydrogel for development of proactive smart textiles. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Aierken, A.; Zhao, L.; Lin, Z.S.; Jiang, J.J.; Li, B.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Hua, J.L.; Tu, Q. hUC-MSCs lyophilized powder loaded polysaccharide ulvan driven functional hydrogel for chronic diabetic wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 288, 119404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, Z.W.; Ye, L.; Tong, Q.; Ming, Y.; Yang, T.Y.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Zhang, L.H.; Li, X.C.; Deng, H.Z.; Liu, J.; et al. Thermostimulated shrinking and adhesive hydrogel dressing for treating chronic diabetic wounds. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.Y.; Tuo, P.; Li, H.J.; Mei, H.Y.; Yuan, Y.H.; Naeem, A.; Wang, X.L. Phosphate-responsive nanocomposite hydrogel laden with umbilical cord blood exosomes and nanosilver accelerates diabetic and infectious wound healing. Arab. J. Chem. 2025, 18, 1032024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalirajan, C.; Palanisamy, T. Bioengineered hybrid collagen scaffold tethered with silver-catechin nanocomposite modulates angiogenesis and TGF-β toward scarless healing in chronic deep second degree infected burns. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 2000247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.Y.; Zhang, M.; Huang, R.; Li, H.Y.; Lv, W.X.; Lin, X.J.; Huang, R.Q.; Wang, Y. Diabetes immunity-modulated multifunctional hydrogel with cascade enzyme catalytic activity for bacterial wound treatment. Biomaterials 2022, 289, 121790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.R.; Liu, X.L.; Tang, Y.; Bi, X.Y.; He, H.Y.; Sun, X.H.; Sui, Q.; Li, D.L.; Liu, W.C.; Liang, D.D.; et al. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 nanocomposite hydrogels for diabetic wound healing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 8, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Zeng, H.J.; Chen, Z.Y.; Ge, Z.L.; Wang, B.; Liu, B.; Fan, Z.J. Sprayable methacrylic anhydride-modified gelatin hydrogel combined with bionic neutrophils nanoparticles for scar-free wound healing of diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.L.; Zheng, J.Y.; Zhong, Z.W.; Ding, W.; Huang, Y.L.; Liu, Z.R.; Chen, X.Y.; Yang, W.Y.; Shi, S.; Jin, B.; et al. An antibacterial and anti-inflammatory hemostatic adhesive with dual Zn2+ and NO release for the neurovascular electrostimulation of infected diabetic wounds. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 202502097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.L.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhou, S.Z.; Fang, D.; Luo, D.H.; Ran, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Xu, C.; Cao, J.H.; Li, X.D.; et al. A versatile and double cross-linked hydrogel with potent antibacterial and immunomodulatory Zn@Met nanocomplexes for enhanced diabetic-infected wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 163942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Duan, X.M.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.R.; Ni, S.; Wu, S.; Han, Z.Q.; Deng, W.Q.; Sun, D.; et al. Carbon-dot-Zn2+ assembly hybrid multifunctional hydrogels for synergistically monitoring local glucose and repairing diabetic wound. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 38874–38889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.X.; Li, H.S.; Zhou, M.; Ling, G.X.; Zhang, P. Smart bilayer hydrogels based on chitosan and its derivatives for wound repair and visual detection of blood glucose by triggering a cascade enzyme system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 144021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.Q.; Lan, J.X.; Li, J.H.; Song, Y.B.; Wang, X.L.; Zhao, Y.S.; Yuan, Y. A novel bola-molecular self-assembling hydrogel for enhancing diabetic wound healing. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 659, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.S.; Chen, S.Y.; Yi, J.; Zhang, H.F.; Ameer, G.A. A cooperative copper metal-organic framework-hydrogel system improves wound healing in diabetes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1604872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Q.F.; Lu, H.T.; Qiu, X.P.; Zhou, D.F.; Qi, Y.X.; Huang, Y.B. Dual cross-linked HHA hydrogel supplies and regulates MΦ2 for synergistic improvement of immunocompromise and impaired angiogenesis to enhance diabetic chronic wound healing. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3795–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Ma, Q.; Xu, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.G.; Liu, H.Z. Polydopamine reduced graphene oxide/chitosan-based hydrogel for the therapy of diabetic wound. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Su, Y.; Zhao, T.E.; Ren, R.Y.; Chi, Z.; Liu, C.G. An injectable hydrogel of enteromorpha polysaccharide/gelatin-derivatives inspired by siderophores and biocatalysis for addressing all phases of chronic diabetic wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Xu, Z.Y.; Cui, C.Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.F.; Xiao, M.; Fan, C.C.; Wu, T.L.; Yang, J.H.; Liu, W.G. A Fe3+-crosslinked pyrogallol-tethered gelatin adhesive hydrogel with antibacterial activity for wound healing. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 3164–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.J.; Zhang, M.; Lv, W.X.; Li, J.; Huang, R.; Wang, Y. Engineering carbon nanotube-based photoactive COF to synergistically arm a multifunctional antibacterial hydrogel. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 202310845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Qi, Y.C.; Liu, W.C.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Li, W.; Zhu, H.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J.H. Multifunctional gastrodia elata polysaccharide-based triple-network hydrogel promotes Staphylococcus aureus infected diabetes wound. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 367, 123983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.J.; Ma, R.; Chen, J.; Qiu, J.M.; Du, S.; Li, C.C.; Wu, Z.H.; Yang, X.F.; Chen, Z.B.; et al. Thermosensitive hydrogel incorporating prussian blue nanoparticles promotes diabetic wound healing via ROS scavenging and mitochondrial function restoration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 14059–14071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.T.; Zhang, J.M.; Lai, J.W.; Deng, M.J.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Xia, Z.B.; Zhong, C.Y.; Feng, X.Y.; Hu, Y.M.; Guo, X.R.; et al. Prussian blue nanohybrid hydrogel combined with specific far-infrared based on graphene devices for promoting diabetic wound healing. Mater. Des. 2025, 253, 113839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

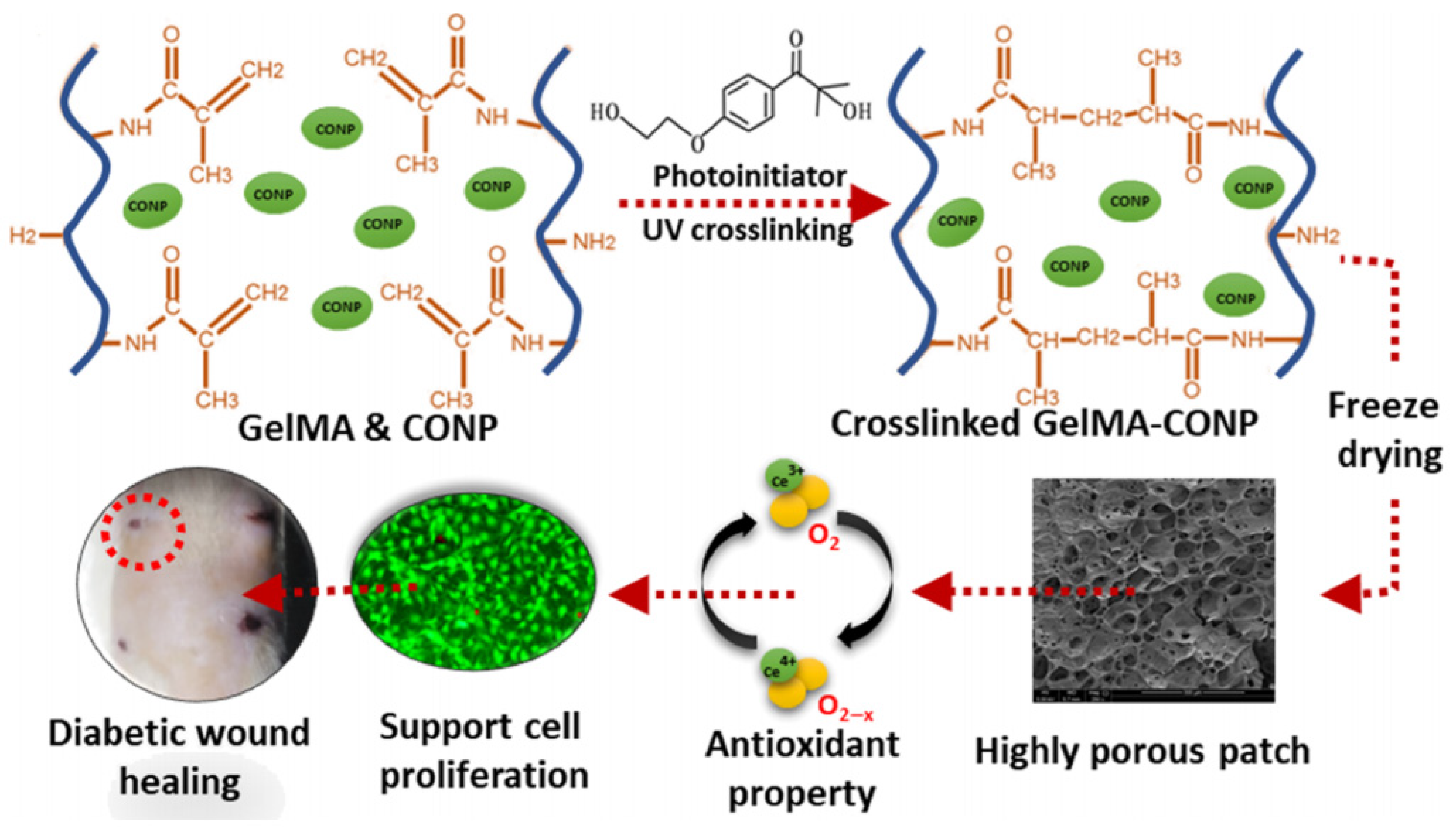

- Dong, H.; Li, J.; Huang, X.Y.; Liu, H.T.; Gui, R. Platelet-membrane camouflaged cerium nanoparticle-embedded gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel for accelerated diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.H.; Ling, J.H.; Wang, N.; Ouyang, X.K. Cerium dioxide nanozyme doped hybrid hydrogel with antioxidant and antibacterial abilities for promoting diabetic wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, R.; Zahid, A.A.; Hasan, A.; Dalvi, Y.B.; Jacob, J. Cerium oxide nanoparticle-loaded gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel wound-healing patch with free radical scavenging activity. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Al Mamun, A.; Zaidi, M.B.; Roome, T.; Hasan, A. A calcium peroxide incorporated oxygen releasing chitosan-PVA patch for diabetic wound healing. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.R.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.Y.; Huang, R.F.; Li, L.; Huang, X.P.; Shao, Q.; Lin, W.Q.; et al. Multifunctional hydrogel of recombinant humanized collagen loaded with MSCs and MnO2 accelerates chronic diabetic wound healing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 3188–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Liu, X.W.; Sui, B.Y.; Wang, J.L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z. Using hybrid MnO2-Au nanoflowers to accelerate ROS scavenging and wound healing in diabetes. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.P.; Wang, X.Y.; Ren, M.J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.M.; Qiang, T.T.; Dong, L.Y.; Wang, X.H. Promoting the healing of infected diabetic wound by nanozyme-containing hydrogel with anti-bacterial inflammation suppressing, ROS-scavenging and oxygen-generating properties. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2024, 112, e35458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.L.; Dong, M.D.; Han, Q.Q.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yang, D.Z.; Wei, D.Q.; Yang, Y.L. Enhancing diabetic wound healing with a pH-responsive nanozyme hydrogel featuring multi-enzyme-like activities and oxygen self-supply. J. Control. Release 2024, 365, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.W.; Dong, X.Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.J.; Yang, H.J.; Zhang, D.; Yu, A.X. ROS-responsive hydrogel enables drug/ion/gas co-delivery for improving survival of multi-territory perforator flap in diabetes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 202500586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.B.; Wang, J.P.; Zhang, X.M.; Yin, C.X. Nanoscale and hollow inorganic sulfide@porous organic network doped intelligent hydrogels for accelerating diabetes wound therapeutics. Sci. China Chem. 2025, 68, 3175–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y.N.; Si, J.H.; Zhang, R.K.; Ji, Y.L.; Fan, J.J.; Dong, Y.Z. Glucose-activated nanozyme hydrogels for microenvironment modulation via cascade reaction in diabetic wound. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ou, X.L.; Guan, L.; Li, X.C.; Liu, A.A.; Li, L.; Zvyagin, A.; Qu, W.R.; Yang, B.; Lin, Q. Pomegranate-inspired multifunctional nanocomposite wound dressing for intelligent self-monitoring and promoting diabetic wound healing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 235, 115386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.J.; Wang, P.H.; Yang, R.; Tan, X.Y.; Shi, T.Q.; Ma, J.P.; Xue, W.L.; Chi, B. Bio-fabricated nanocomposite hydrogel with ROS scavenging and local oxygenation accelerates diabetic wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 4083–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.L.; He, J.; Qiao, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, R.X.; Xu, W.; Wang, F.; Yang, S.H.; Zhang, X.C.; et al. Multifunctional dual network hydrogel loaded with novel tea polyphenol magnesium nanoparticles accelerates wound repair of MRSA infected diabetes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 202312140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Li, W.; Fan, Y.Z.; Xiao, C.R.; Shi, Z.F.; Chang, Y.B.; Liang, G.Y.; Liu, C.L.; Zhu, Z.R.; Yu, P.; et al. Localized surface plasmon resonance-enhanced photocatalytic antibacterial of in situ sprayed 0D/2D heterojunction composite hydrogel for treating diabetic wound. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 202303836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Y.; Zhu, J.J.; Sun, W.C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.Y.; He, Y.N.; Qin, J.L. Antibacterial betaine modified chitosan-based hydrogel with angiogenic property for photothermal enhanced diabetic wound repairing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 349, 123033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordeghan, A.N.; Khayatan, D.; Saki, M.R.; Alam, M.; Abbasi, K.; Shirvani, H.; Yazdanian, M.; Soufdoost, R.S.; Raad, H.T.; Karami, A.; et al. The wound healing effect of nanoclay, collagen, and tadalafil in diabetic rats: An in vivo study. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9222003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Yan, C.Y.; Ma, R.T.; Dai, L.; Shu, W.J.; Asghar, A.; Jia, Z.G.; Zhu, X.L.; Yu, S. E-PL/MnO2 nanozymes/gellan gum/hyaluronic acid-based multifunctional hydrogel to promote diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 304, 140777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.L.; You, X.Y.; Wu, S.Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Hu, D.; Ma, Y.S.; Luo, J.; Qiu, J.; Zhou, L.H. Remolding waste liquid from the zeolite synthesis process into wrinkled dressings for diabetic wound therapeutics with immunomodulation. Energy Environ. Mater. 2025, 8, 70072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Qi, C.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, B.; Zhou, M.; Lin, Y.F. A sprayable nucleic acid hydrogel for diabetic wound healing via immunomodulation and angiogenesis. Small 2025, 21, 202506587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tang, X.Y.; Chen, X.; Ma, H.S.; Zhong, H.Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Tang, J.; Sun, Q.; Gao, S.J.Y. Thermoelectric bionic skin promotes diabetic wound healing by restoring bioelectric field microenvironment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e22104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzeska, A.; Krasinska, N.; Kitlas, P. Effects of Phallus impudicus extract for accelerating hard-healing wounds in diabetes-induced rats. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2024, 81, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Gao, M.Z.; Boakye-Yiadom, K.O.; Ho, W.; Yu, W.; Xu, X.Y.; Zhang, X.Q. An intrinsically bioactive hydrogel with on-demand drug release behaviors for diabetic wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4592–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, C.; Dai, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, H.Y.; Peng, Y.B.; Chu, Y.F.; Chen, Z.; Qin, H.T.; Zeng, H. Injectable cinnamaldehyde-loaded ZIF-8/Gallic Acid-Grafted gelatin hydrogel for enhanced angiogenesis and skin regeneration in diabetic wound healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2025, 13, 1660821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Duan, L.Y.; Xu, X.M.; Hu, Y.S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.P.; Bao, H.H.; Liu, T.L. Cu-Doped-ZnO nanocrystals induce hepatocyte autophagy by oxidative stress pathway. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Doping Method | Cross-Linking Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Physical Doping | Non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking) | Mild preparation conditions; Simple and straightforward procedure; Broad applicability; Excellent retention of intrinsic properties. | Poor dispersion of the metal based materials; Leakage of metal ions or particles; Potential biosafety concerns; Structural disruption of the hydrogel network; Compromised mechanical properties. | [40,41,42,43] |

Chemical Doping | Covalent and coordination interactions (coordination bonds, Schiff base bonds, boronic ester bonds, amide bonds) | Enhanced stability; Homogeneous distribution of metal ions/particles; Controlled release of metal ions/particles; Improved mechanical properties. | Complex and demanding preparation process; Altered hydrogel mechanical properties; Potential safety concerns; Limited functional flexibility and reversibility. | [44,45,46] |

Hybrid Doping | Combination of physical and chemical methods (e.g., coordination bonds and hydrogen bonding/π-π stacking) | Synergistic structural stability; Enhanced functional diversity; Formation of interpenetrating networks; Superior mechanical properties; Successful functional integration. | Stringent process control and poor reproducibility; Difficulty in achieving interfacial compatibility and uniform distribution; Unpredictable interference between different networks; Increased risk of structural defects; Unpredictable mechanical performance. | [47,48] |

| Metal Type | Function Category | Mechanism | Therapeutic Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Ag | Antibacterial | Disrupts bacterial cell membranes; interferes with DNA replication; denatures proteins | Broad-spectrum antibacterial activity; low risk of resistance | [41,62,63,64] |

| Angiogenesis and re-epithelialization | Synergizes with functional molecules (e.g., insulin) to promote cell migration and proliferation | Accelerates wound closure; promotes granulation tissue formation | ||

| Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory | Scavenges ROS; induces macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype | Alleviates oxidative stress and inflammation; improves healing microenvironment | ||

Zn | Antibacterial and anti-inflammatory | Disrupts bacterial membranes; inhibits metabolic enzymes; downregulates pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-6) | Alleviates chronic inflammation; effectively clears bacteria | [65,66,67] |

| Pro-healing and immunomodulation | Promotes fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition; regulates macrophage M1/M2 polarization | Accelerates wound closure and tissue remodeling; facilitates scarless repair | ||

| Smart response/ Theranostics | Responsive release; monitoring of glucose | On-demand therapy; integrates diagnosis and treatment functions | ||

Cu | Antibacterial | Generates ROS; disrupts bacterial membrane integrity | Highly efficient bactericidal activity; effective against drug-resistant bacteria | [43,68] |

| Angiogenesis | Promotes vascular endothelial cell proliferation and migration | Improves ischemic and hypoxic microenvironment; accelerates angiogenesis | ||

| Immunomodulation | Modulates macrophage polarization; promotes transition to M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype | Alleviates chronic inflammation; promotes inflammation resolution | ||

Fe | Antibacterial | Fenton-like reaction produces ROS; directly disrupts bacterial cell structure; photothermal effect generates heat | Provides a potent antibacterial effect | [58,69,70] |

| Antioxidant | Mimics nanozyme activity to scavenge ROS | Alleviates oxidative stress | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | Regulates macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 phenotype | Downregulates TNF-α, IL-1β; upregulates IL-10, TGF-β1; alleviates excessive inflammation | ||

| Oxygenation | Decomposes H2O2 to release O2 | Alleviates tissue hypoxia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Gao, H.; Mayo, K.H.; Mo, J.; Deng, L. Multifunctional Metal Composite Hydrogels for Diabetic Wound Therapy. Gels 2025, 11, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120960

Zhang S, Gao H, Mayo KH, Mo J, Deng L. Multifunctional Metal Composite Hydrogels for Diabetic Wound Therapy. Gels. 2025; 11(12):960. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120960

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shengnan, Hui Gao, Kevin H. Mayo, Jingang Mo, and Le Deng. 2025. "Multifunctional Metal Composite Hydrogels for Diabetic Wound Therapy" Gels 11, no. 12: 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120960

APA StyleZhang, S., Gao, H., Mayo, K. H., Mo, J., & Deng, L. (2025). Multifunctional Metal Composite Hydrogels for Diabetic Wound Therapy. Gels, 11(12), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120960