1. Introduction

Red mold rice (RMR), which is fermented from rice using

Monascus spp., is a traditional food product with a history of over a thousand years in China [

1,

2]. It is widely used as a natural food colorant, preservative, and ingredient in the production of rice wine, vinegar, and meat products. Beyond its culinary applications, RMR is also recognized for its functional properties, including antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory effects, leading to its classification as functional RMR [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. With an annual production of approximately 20,000 tons in China and over 100 million people consuming

Monascus-derived products daily [

6], research into the high-efficiency synthesis mechanisms of

Monascus pigments (MPs) has gained significant importance.

Monascus pigments are a mixture of compounds and are typically classified into the following three groups based on their absorption spectra: yellow (330–450 nm), orange (460–480 nm), and red (490–530 nm) pigments [

6,

7]. According to solubility, they can be divided into water-soluble and alcohol-soluble forms, with the latter being the predominant intracellular form [

6]. They are secondary metabolites synthesized via the polyketide pathway, using acetyl-CoA as a precursor [

8]. The biosynthesis pathway involves key enzymes such as polyketide synthase (PKS) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) [

8]. Recent genomic studies have identified a gene cluster spanning approximately 53 kb responsible for MP biosynthesis, which includes genes encoding PKS, FAS, regulatory proteins, and transporters [

1].

Nitrogen sources, particularly amino acids, play a critical role in regulating MP biosynthesis and composition. It is proposed that the orange pigment is directly synthesized via the polyketide pathway, the yellow pigment is formed by the reduction in the orange pigment using reducing equivalents (e.g., NADPH), and the red pigment is generated through the amination of the orange pigment, utilizing amino groups derived from amino acid metabolism [

5,

6]. Specific amino acids have been shown to differentially influence the pigment profile. For instance, supplementation with phenylalanine, valine, leucine, and isoleucine increased the proportion of yellow and orange pigments in

Monascus sp. KCCM 10093, while serine, histidine, glycine, and alanine favored the production of red pigments [

9]. Similarly, histidine, glycine, arginine, tyrosine, and serine significantly promoted red pigment formation in

Monascus ruber ATCC 96218 [

10], with arginine suggested as a key amino group donor [

6]. Beyond specific amino acids, inorganic nitrogen sources like ammonium sulfate can also alter pigment composition, increasing the proportion of intracellular red pigments while decreasing yellow pigments [

11]. These findings underscore the intricate interplay between nitrogen metabolism and MP synthesis.

Numerous studies have explored strategies to enhance MP production by modulating central metabolic pathways. In

Monascus ruber CICC41233, heterologous expression of the α-amylase gene AOamyA from

Aspergillus oryzae resulted in the engineered strain

Monascus ruber Amy9. When fermented with rice as the substrate, starch was completely degraded in the Amy9 strain after 2 days, whereas the wild-type strain still retained residual starch even after 6 days of fermentation. After 6 days of fermentation, the yield of

Monascus pigments in the engineered strain

M. ruber Amy9 increased by 132% compared to the wild-type strain [

12]. Furthermore, overexpression of the gene encoding the endogenous α-amylase MrAMY1 in

M. ruber CICC41233 (which shares up to 69% homology with AOamyA) led to complete starch degradation in the resulting engineered strain within 2 days. After 6 days of fermentation, the pigment color value increased by 71.69% compared to the wild-type strain [

13]. These results demonstrate a positive correlation between the rapid degradation of starch and the production of

Monascus pigments. Overexpression of ATP-citrate lyase (ACL) increases acetyl-CoA supply and boosts pigment yield [

14]. Modulation of fatty acid metabolism, such as knocking out the ergosterol biosynthesis gene

ERG4 or overexpressing acyl-CoA binding proteins (ACBPs), redirects metabolic flux toward pigment synthesis [

15,

16,

17]. Furthermore, key regulatory elements, including the global regulator

LaeA [

18], the carbon catabolite repressor

CreA [

5], and G-protein signaling components (e.g.,

mga1,

flbA), have been identified as critical modulators of MP biosynthesis [

19,

20,

21].

Our preliminary results indicated that

M. ruber CICC41233 produced substantial amounts of

Monascus pigments after 2 days of fermentation using rice as the substrate, whereas no pigment production was observed when glucose was used as the carbon source under the same conditions. Transcriptome sequencing revealed that among the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) monosaccharide transporters, only one glucose transporter (designated GLTP1), encoded by the gene

gltp1, was significantly upregulated. The expression level (FPKM values) of

gltp1 was 4506.55 in rice-based fermentation and 1389.04 in glucose-based fermentation (unpublished data). In the

M. ruber NRRL1597 genome database (

https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/Monru1/Monru1.home.html) (accessed on 20 September 2016), this transporter also exhibited 67% homology with glucose transporters from

Aspergillus species, such as

Aspergillus fumigatus Af293 (Afu2g11520) and

Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4 (AN5860). These proteins belong to the low-affinity glucose transporter family, which enables rapid sensing of high glucose concentrations in the environment.

Therefore, this study aims to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which GLTP1 influences Monascus pigment synthesis in M. ruber. Using genetic approaches including gene knockout, complementation, and overexpression, combined with transcriptomic analyses, we seek to uncover the regulatory network connecting glucose transport and pigment biosynthesis. This research will not only advance our understanding of the crosstalk between primary and secondary metabolism in M. ruber, but also provide a theoretical foundation for enhancing the industrial production of Monascus pigments.

3. Results and Discussion

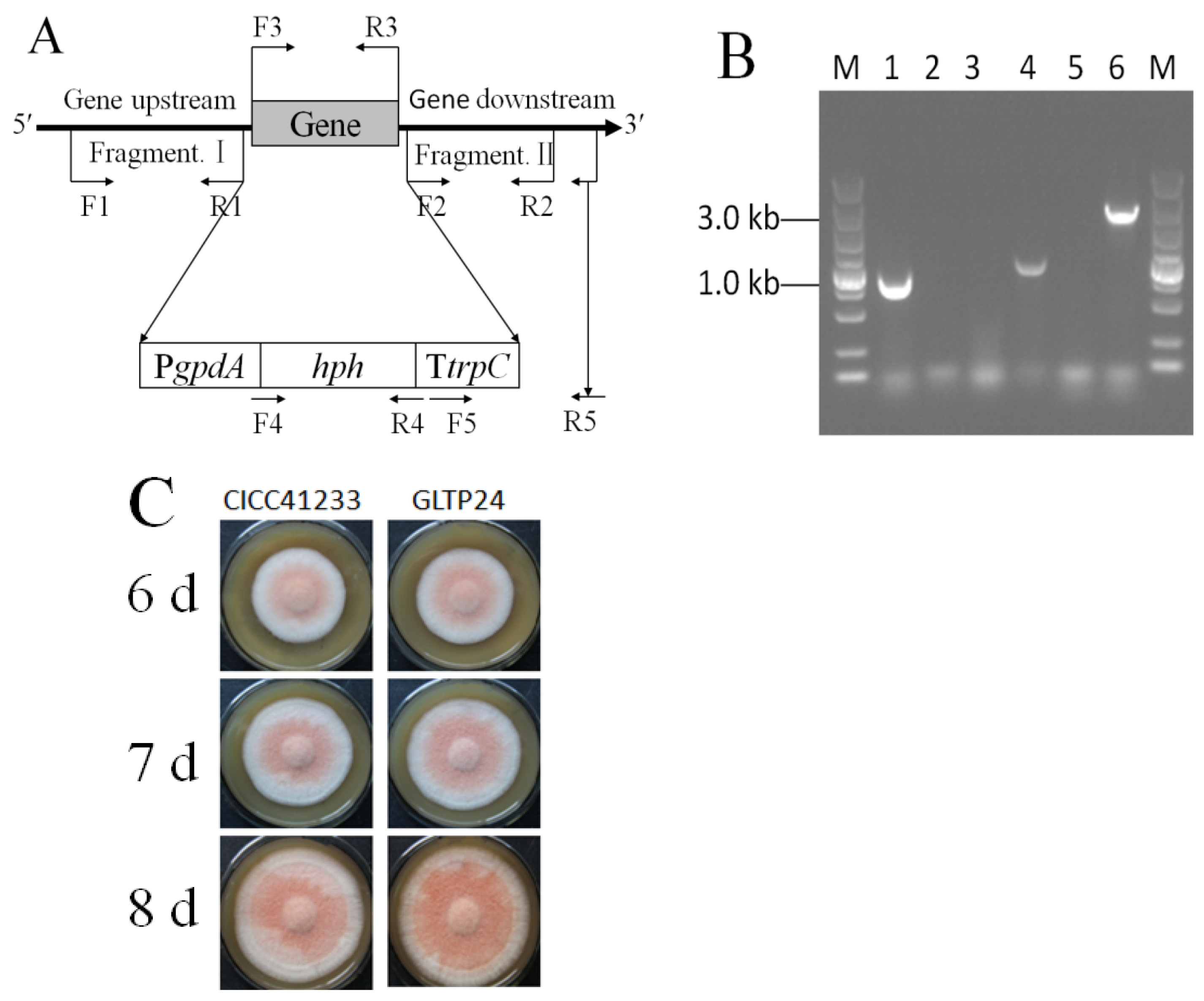

3.1. Obtain the Δgltp1 Mutant Strain

The gltp1 gene was cloned from M. ruber CICC41233, and its sequence was subjected to NCBI Nucleotide BLAST analysis. It showed the highest homology (97%) with the hexose transporter hxt1 (TQB68571.1) of Monascus purpureus.

Then, the

A. tumefaciens EHA105 mediated transformation of pHph0380G/Gltp1::hph into

M. ruber CICC41233, with nine transformants initially selected and confirmed to exhibit mitotic stability. Subsequent PCR analysis of genomic DNA from these candidates, however, demonstrated that only one was positive. Firstly, the primers G129444-JYF-HindIII (F3) and G129444-JYR-SacI (R3) were used to detect the

gltp1 gene (948 bp), which was present in the parental strain but was absent in the Δ

gltp1 mutant (

Figure 1A,B). At the same time, the primers Hph-1034F (F4) and Hph-1034R (R4) were used to detect

hph gene (1034 bp), which was absent in the parental strain but was present in the Δ

gltp1 mutant (

Figure 1A,B). Then, the primers HtrpC-YZF (F5) and G129444-YZR (R5) were used to verify that the hph cassettes (2644 bp) were successfully inserted into the

gltp1 locus in the Δ

gltp1 mutant (

Figure 1A,B). Therefore, the mutant was named

M. ruber GLTP24. The phenotype of the parental strain

M. ruber CICC41233 and mutant

M. ruber GLTP24 were grown on MPS for 7 d, 8 d, and 9 d (

Figure 1C). The Δ

gltp1 mutant grew denser than the parental strain (

Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Schematic map of the primer locus for knocking out gltp1 (A) and identification of mutant M. ruber GLTP24 by PCR (B) and phenotype of M. ruber (C). (A) F1, primer G129444-QC-UF-PstI; R1, primer G129444-QC-UR-SacI. F2, primer G129444-QC-DF-BglII; R2, primer G129444-QC-DR-SpeI. F3, G129444-JYF-HindIII; R3, primer G129444-JYR-SacI. F4, primer Hph-1034F; R4, primer Hph-1034R. F5, primer HtrpC-YZF; R5, primer G129444-YZR. (B) The fragments of lanes 1 and 2 were products of the primers F3 and R3 test. The fragments of lanes 3 and 4 were products of the primers F4 and R4 test. The fragments of lanes 5 and 6 were products of the primers F5 and R5 test. Lanes 1, 3, and 5 represent the genomic DNA as the template from the parental strain M. ruber CICC41233; lanes 2, 4, and 6 represent the genomic DNA as the template from the mutaint strain M. ruber GLTP24. M: DL5000 bp DNA Ladder Marker. (C) Phenotype of M. ruber grown on MPS medium.

Figure 1.

Schematic map of the primer locus for knocking out gltp1 (A) and identification of mutant M. ruber GLTP24 by PCR (B) and phenotype of M. ruber (C). (A) F1, primer G129444-QC-UF-PstI; R1, primer G129444-QC-UR-SacI. F2, primer G129444-QC-DF-BglII; R2, primer G129444-QC-DR-SpeI. F3, G129444-JYF-HindIII; R3, primer G129444-JYR-SacI. F4, primer Hph-1034F; R4, primer Hph-1034R. F5, primer HtrpC-YZF; R5, primer G129444-YZR. (B) The fragments of lanes 1 and 2 were products of the primers F3 and R3 test. The fragments of lanes 3 and 4 were products of the primers F4 and R4 test. The fragments of lanes 5 and 6 were products of the primers F5 and R5 test. Lanes 1, 3, and 5 represent the genomic DNA as the template from the parental strain M. ruber CICC41233; lanes 2, 4, and 6 represent the genomic DNA as the template from the mutaint strain M. ruber GLTP24. M: DL5000 bp DNA Ladder Marker. (C) Phenotype of M. ruber grown on MPS medium.

3.2. Construct Engineered Strains with the gltp1 Gene Complementation and Overexpression Strains

Then, the gltp1 gene was homologously overexpressed in M. ruber CICC41233, and three transformants tested positive, named as M. ruber OE3, M. ruber OE4, and M. ruber OE7 (the molecular identification results were not presented). The gltp1 gene was expressed in the mutant strain M. ruber GLTP24, and three complementary strains tested positive, named as M. ruber HU1, M. ruber HU 6, and M. ruber HU 17 (the molecular identification results are not presented).

3.3. Comparison of MPs’ Production in M. ruber CICC41233 and Mutant M. ruber GLTP24

The phenotypic appearance of

M. ruber CICC41233 and

M. ruber GLTP24 fermented using rice flour as the substrate for pigment production is shown in

Figure 2A. At 36 h, the mutant strain yielded significantly higher amounts of visual

Monascus pigments than the parental strain. The biomass production showed no significant difference between the strains.

More significantly, during fermentation with rice flour, the mutant strain displayed a dramatic acceleration in starch consumption. The residual starch content in the

M. ruber CICC41233 fermentation samples at 36 h, 48 h, and 144 h was 44.91 mg/mL, 34.26 mg/mL, and 9.58 mg/mL, respectively. In contrast,

M. ruber GLTP24 showed significantly lower levels, as follows: 0.56 mg/mL, 0.15 mg/mL, and 0 mg/mL, respectively (

Figure 2B).

Concomitant with rapid starch degradation, the

M. ruber GLTP24 mutant produced significantly higher yields of

Monascus pigments (MPs). The pigment yield of

M. ruber GLTP24 (49.46 U/mL) was significantly higher than that of

M. ruber CICC41233 (28.42 U/mL) at 144 h. The results demonstrate that

M. ruber GLTP24 can enhance the production of yellow and red pigments in the alcohol-soluble fraction of

Monascus pigments (

Figure 2C,E) [

6]. This establishes a clear positive correlation between the rate of starch degradation and the yield of key MPs, a phenomenon supported by previous studies where accelerated starch hydrolysis led to increased pigment production [

12,

13]. However, the production of yellow and red pigments in the water-soluble fraction of

Monascus pigments saw a slight decrease (

Figure 2C,D).

As a low-affinity glucose transporter, GLTP1 can transport extracellular glucose. Consequently, knockout of the

gltp1 gene resulted in a significant difference in extracellular glucose concentration between

M. ruber CICC41233 and

M. ruber GLTP24 (

Figure 2F). This indicates that the deletion of the

gltp1 glucose transporter paradoxically enhances the degradation of starch.

Our findings depict GLTP1 not merely as a glucose transporter, but as a critical metabolic regulator that couples carbon sensing with secondary metabolism. The observation that its deletion enhances starch degradation suggests that GLTP1 may be involved in a carbon catabolite repression (CCR) mechanism. In many fungi, efficient glucose uptake through specific transporters sustains CCR, repressing the expression of genes for utilizing alternative carbon sources (like starch) and the synthesis of secondary metabolites [

5,

22].

We propose a model wherein the knockout of

gltp1 disrupts this repression signal. The inability to efficiently transport glucose, despite its availability from starch hydrolysis, may be perceived by the cell as a carbon-limited state. This is consistent with the observed downregulation of carbon-sensing components like the G-protein-coupled receptor GprD and the protein kinase Pka-C3 in the mutant, which are part of a signaling cascade known to influence fungal development and secondary metabolism [

21,

22,

23].

In conclusion, GLTP1 serves as a key metabolic gatekeeper. Its deletion deregulates carbon catabolite repression, leading to accelerated starch assimilation and a rechanneling of carbon flux towards the enhanced biosynthesis of Monascus pigments.

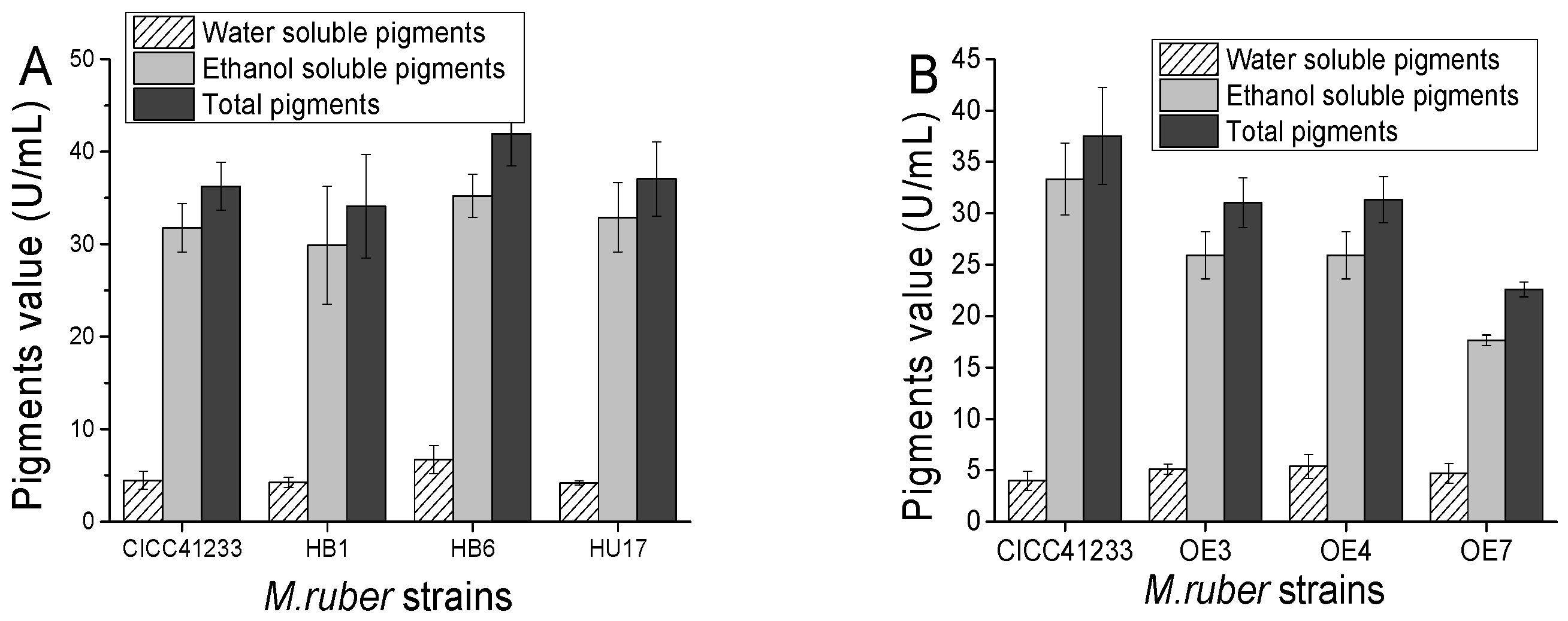

3.4. Comparison of MPs’ Production in M. ruber CICC41233 and Complementation and Overexpression Strains

To further verify the impact of the

gltp1 gene on

Monascus pigment production in

M. ruber, the functional role of

gltp1 was unequivocally confirmed by reverse genetics. The complementary strains (

M. ruber HU1,

M. ruber HU6, and

M. ruber HU17), in which the

gltp1 gene was restored, showed recovery of the wild-type phenotype, with no significant difference in MPs’ production compared to

M. ruber CICC41233 (

Figure 3A). This demonstrates that the hyper-producing phenotype of the

M. ruber GLTP24 mutant is directly attributable to the loss of

gltp1.

Conversely, overexpressing

gltp1 led to a contrasting effect. The overexpression strains (

M. ruber OE3,

M. ruber OE4, and

M. ruber OE7) consistently produced lower levels of alcohol-soluble and total pigments compared to the wild-type (

Figure 3B). The expression levels of the

gltp1 gene are shown in

Figure 4A. In comparison with

M. ruber CICC41233, the expression fold of

gltp1 increased by 3.38-, 4.50-, and 2.84-fold in

M. ruber OE3,

M. ruber OE4, and

M. ruber OE7 after 6 days, respectively. This inverse relationship between

gltp1 expression levels and pigment yield provides compelling evidence that GLTP1 acts as a negative regulator of MPs’ biosynthesis.

3.5. Global Transcriptional Reprogramming Induced by gltp1 Deletion

The raw transcriptome data are available in the NCBI database under the accession number PRJNA1370451. The deletion of the

gltp1 gene in

M. ruber triggered extensive transcriptional changes, as evidenced by the high number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) when comparing the mutant (

M. ruber GLTP24) to the wild-type (

M. ruber CICC41233) at both 36 h (S01 vs. S02, 1249 DEGs) and 144 h (S03 vs. S04, 1041 DEGs) of fermentation (

Table 1). qRT-PCR was performed to corroborate the transcriptomic data obtained from RNA-seq (

Figure 4B). In both comparisons, the number of downregulated genes surpassed that of upregulated genes, indicating that the loss of this glucose transporter primarily exerts a repressive effect on a broad spectrum of cellular functions.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of these DEGs provided crucial insights into the metabolic rewiring caused by the

gltp1 knockout and its direct implications for

Monascus pigment (MP) biosynthesis (

Table 2,

Supplementary Figure S1).

In the early fermentation stage of 36 h (S01 vs. S02 group), DEGs were significantly enriched in pathways central to primary metabolism. These included “Microbial metabolism in diverse environments,” “Pyruvate metabolism,” “Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism,” and “Glycerolipid metabolism.” The enrichment of these pathways indicates a major rerouting of central carbon flux. Pyruvate is a key hub for generating acetyl-CoA, the essential building block for the polyketide backbone of all MPs [

8,

14]. The glyoxylate cycle can replenish C4 metabolites, supporting energy production and biosynthesis when glucose is scarce, a condition potentially mimicked by the disrupted glucose sensing in the mutant [

22].

Most notably, concerted enrichment was observed in multiple amino acid metabolism pathways, as follows: “beta-Alanine metabolism,” “Phenylalanine metabolism,” “Arginine and proline metabolism,” “Tryptophan metabolism,” “Tyrosine metabolism,” and “Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation.” This is highly significant for MP synthesis. The degradation of branched-chain amino acids (Val, Leu, and Ile) directly supplies acetyl-CoA [

8]. More importantly, amino acids like phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, and particularly arginine are known to serve as preferential amino group donors for the conversion of orange pigments to red pigments [

6,

9,

10,

24]. The transcriptional rewiring of these pathways in the

gltp1 mutant suggests a strategic cellular response to enhance the provision of both carbon skeletons and amino groups, thereby priming the metabolic network for efficient MP production, especially the red components.

By the late stage of 144 h (S03 vs. S04 group), the enrichment profile shifted dramatically towards pathways essential for cellular biosynthesis and maintenance, as follows: “Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes,” “Purine metabolism,” “Pyrimidine metabolism,” and “Sulfur metabolism.” This indicates a reallocation of resources to bolster the cell’s protein synthesis capacity (ribosomes) and nucleotide pools. This shift is critical for supporting the high-level expression and translation of the large enzymatic complexes required for secondary metabolism, such as the polyketide synthase (PKS) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) within the MP gene cluster. Sulfur metabolism is also crucial for the synthesis of methionine and S-adenosylmethionine [

25], which are involved in various cellular methylation reactions and could influence secondary metabolite profiles. The sustained enrichment in “Microbial metabolism in diverse environments” underscores the continued global metabolic adjustment in the mutant.

Further analysis of specific genes revealed a targeted impact on signaling pathways. The expression of

gene_390199 (annotated as the G protein-coupled receptor

gprD) was significantly downregulated in the mutant at 36 h. In

Aspergillus bombycis, the GprD protein is part of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) complex [

22]. In

Aspergillus species, this complex has been identified to consist of nine transmembrane proteins (such as GprA-I), along with the Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits forming the G protein trimer, and effectors such as GTPase enzymes [

22].

Concurrently,

gene_473493 (encoding Pka-C3, a catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase) was significantly downregulated at 144 h (FPKM

Table 3). In

Aspergillus oryzae RIB40, Pka-C3 is a catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase, which functions within the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway [

22].

The literature indicates that GPCRs such as GprD (Gpr4 and Gpr1) in fungi (including

Saccharomyces cerevisiae,

Neurospora crassa, and

Aspergillus species such as

Aspergillus nidulans, as well as

Cryptococcus neoformans) primarily function as sensors for extracellular carbon sources like glucose [

22,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], while also serving as receptors for amino acid sensing [

22,

29,

31]. These GPCRs further activate the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway to regulate gene expression, thereby modulating fungal growth, development, and metabolism [

20,

21,

22,

23,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

Recent research by Chen et al. [

21] demonstrated that knockout of the Gα protein-encoding gene in GPCRs significantly promotes

Monascus pigment production in

Monascus spp. fungi. Transcriptome sequencing revealed that in the Gα protein knockout strain, the expression levels of genes related to the TCA cycle, carbon-metabolism-associated MFS transporters, and nitrogen metabolism were downregulated, indicating that the Gα protein negatively regulates the synthesis of this secondary metabolite [

21]. Therefore, the downregulation of MFS transporter genes involved in carbon metabolism further facilitates enhanced

Monascus pigment production. These findings are consistent with our research results.

Our transcriptomic data support a coherent model for how GLTP1 deletion enhances MP production. The loss of GLTP1 disrupts carbon sensing, as evidenced by the suppression of the GprD receptor and the downstream cAMP/PKA pathway. This signaling defect triggers a biphasic metabolic adaptation.

The early phase (36 h) is characterized by a comprehensive reprogramming of central carbon and amino acid metabolism. This creates an abundant pool of essential precursors: acetyl-CoA from pyruvate and branched-chain amino acid degradation for the polyketide chain, and specific amino acids for the amination step that forms red pigments. The late phase (144 h) sees a shift towards enhancing the biosynthetic capacity itself, with resources funneled into ribosome and nucleotide biosynthesis to efficiently translate the MPs biosynthetic machinery. This temporal strategy—early precursor priming followed by late-stage commitment to massive enzyme production—orchestrated by the initial perturbation in carbon signaling, provides a powerful mechanistic explanation for the accelerated starch degradation and significantly higher pigment yield observed in the gltp1 mutant.

3.6. Transcriptional Profiling of the Monascus Pigment Biosynthetic Gene Cluster in the gltp1 Mutant

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the enhanced pigment production in the gltp1 knockout strain M. ruber GLTP24, we performed a comparative transcriptomic analysis focusing on the known Monascus pigment biosynthetic gene cluster between the wild-type M. ruber CICC41233 and the M. ruber GLTP24 mutant at 36 h and 144 h of fermentation.

The results revealed significant differential expression of several key genes within the cluster (

Figure 5,

Table S2). The polyketide synthase gene (

gene_470061), which catalyzes the core backbone synthesis of

Monascus pigments [

1,

34], showed notably lower expression in the

M. ruber GLTP24 mutant at 36 h (FPKM: 153.34 in WT vs. 94.20 in mutant). Conversely, the gene encoding the pathway-specific transcriptional activator PigR (

gene_431934) [

35] exhibited a substantial increase in expression in the mutant at 144 h (FPKM: 73.70 in WT vs. 65.74 in mutant).

Key genes involved in the modification and maturation of pigments also displayed altered expression. The oxidoreductase gene

pigC (

gene_497168) was significantly downregulated in the mutant at 36 h (FPKM: 613.83 in WT vs. 298.88 in mutant). In contrast, another crucial oxidoreductase gene,

MpigH (

gene_380063), was markedly upregulated in the mutant at 144 h (FPKM: 1194.31 in WT vs. 3876.34 in mutant). Furthermore, the fatty acid synthase (FAS) genes (

gene_175502, alpha subunit;

gene_416263, beta subunit), which supply essential fatty acyl precursors for pigment synthesis [

8], were downregulated in the mutant, particularly at 36 h. Interestingly, a gene encoding a Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) transporter (

gene_431958) was significantly upregulated in the mutant at 144 h (FPKM: 150.16 in WT vs. 371.85 in mutant).

The transcriptional changes observed in the

M. ruber GLTP24 mutant provide crucial insights into the regulatory role of the glucose transporter GLTP1 in

Monascus pigment biosynthesis. The initial downregulation of the core polyketide synthase (

gene_470061) and fatty acid synthase genes (

gene_175502,

gene_416263) at 36 h in the mutant may reflect a transient metabolic imbalance or a specific regulatory response to the altered carbon flux resulting from accelerated starch degradation following

gltp1 deletion [

12,

13].

However, the most significant changes occurred at the later fermentation stage (144 h). The upregulation of the pathway-specific transcriptional activator

pigR (

gene_431934) is particularly noteworthy, as its overexpression has been previously shown to dramatically enhance pigment production [

35]. This suggests that the mutation in

gltp1 ultimately leads to the activation of this key regulatory switch. The strong induction of the

MpigH oxidoreductase gene (

gene_380063), which is involved in critical reduction steps during pigment synthesis [

1,

6], aligns perfectly with the experimentally observed increase in total pigment yield and the specific enhancement of yellow and red pigments in the

M. ruber GLTP24 strain. This genetic evidence corroborates our biochemical findings that the

gltp1 knockout strain significantly increased the yields of yellow and red alcohol-soluble pigments.

The concurrent upregulation of a putative MFS transporter (gene_431958) in the mutant suggests a potential enhancement in the transport or secretion of pigments or their intermediates, which could be a secondary factor contributing to the higher measured pigment yield.

Collectively, these transcriptional dynamics demonstrate that the deletion of

gltp1 triggers a comprehensive reprogramming of the pigment biosynthetic gene cluster. The pattern—initial suppression of precursor-supplying pathways followed by strong late-stage activation of key regulatory (

pigR) and biosynthetic (

MpigH) genes—reveals a sophisticated metabolic adaptation. This adaptation likely links the perturbed carbon sensing due to the lack of GLTP1 protein, potentially through the proposed GprD-cAMP/PKA signaling pathway [

21,

22,

23], to the enhanced synthesis of

Monascus pigments. Thus, this study provides a direct molecular link between carbon transport, cluster-specific gene regulation, and secondary metabolite output in

M. ruber.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we elucidated the pivotal role of the glucose transporter GLTP1 in regulating central carbon metabolism and secondary metabolite synthesis in Monascus ruber. GLTP1 is a negative regulator of pigment biosynthesis. Genetic evidence from knockout, complementation, and overexpression strains unequivocally demonstrates that GLTP1 negatively impacts Monascus pigment production. Its deletion is the direct cause of the hyper-production phenotype.

Enhanced pigment yield is linked to accelerated carbon utilization. The gltp1 knockout strain M. ruber GLTP24 exhibited a superior capacity to degrade starch, leading to a significantly increased pool of carbon precursors that fuel the polyketide pathway for MP synthesis, an underlying signaling and metabolic reprogramming mechanism. The transcriptomic data support a model where the loss of GLTP1 perturbs the carbon-sensing mechanism, likely via the GprD-cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. This, in turn, induces a global transcriptional reprogramming that shunts carbon and nitrogen flux towards secondary metabolism, as evidenced by the significant enrichment of amino acid metabolic pathways that provide critical building blocks for pigments.

In summary, this work moves beyond the conventional view of GLTP1 as a mere nutrient transporter and establishes it as a key signaling node that couples carbon availability with the regulation of secondary metabolism. Disrupting this regulator effectively unlocks the inherent potential of M. ruber for high-level pigment production. These findings not only deepen our understanding of the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying MP biosynthesis, but also provide a promising strategic basis for the metabolic engineering of industrial Monascus strains.