In Vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal, Nematocidal and Growth Promoting Activities of Trichoderma hamatum FB10 and Its Secondary Metabolites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of Trichoderma Strains

2.2. Production of Secondary Metabolites

2.3. Extraction of Secondary Metabolites

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity

2.5. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration Determination

2.6. GC-MS Analysis of Secondary Metabolites

2.7. Nematicidal Property

2.8. Hydrolytic Enzyme Production by the Fungal Strain

2.9. Analysis of T. hamatum FB10 on Growth Promoting Activity in Plants

2.10. Analysis of Enzymes in the Soil

3. Results

3.1. Identifications of Secondary Metabolites from the Crude Ethyl Acetate Extract

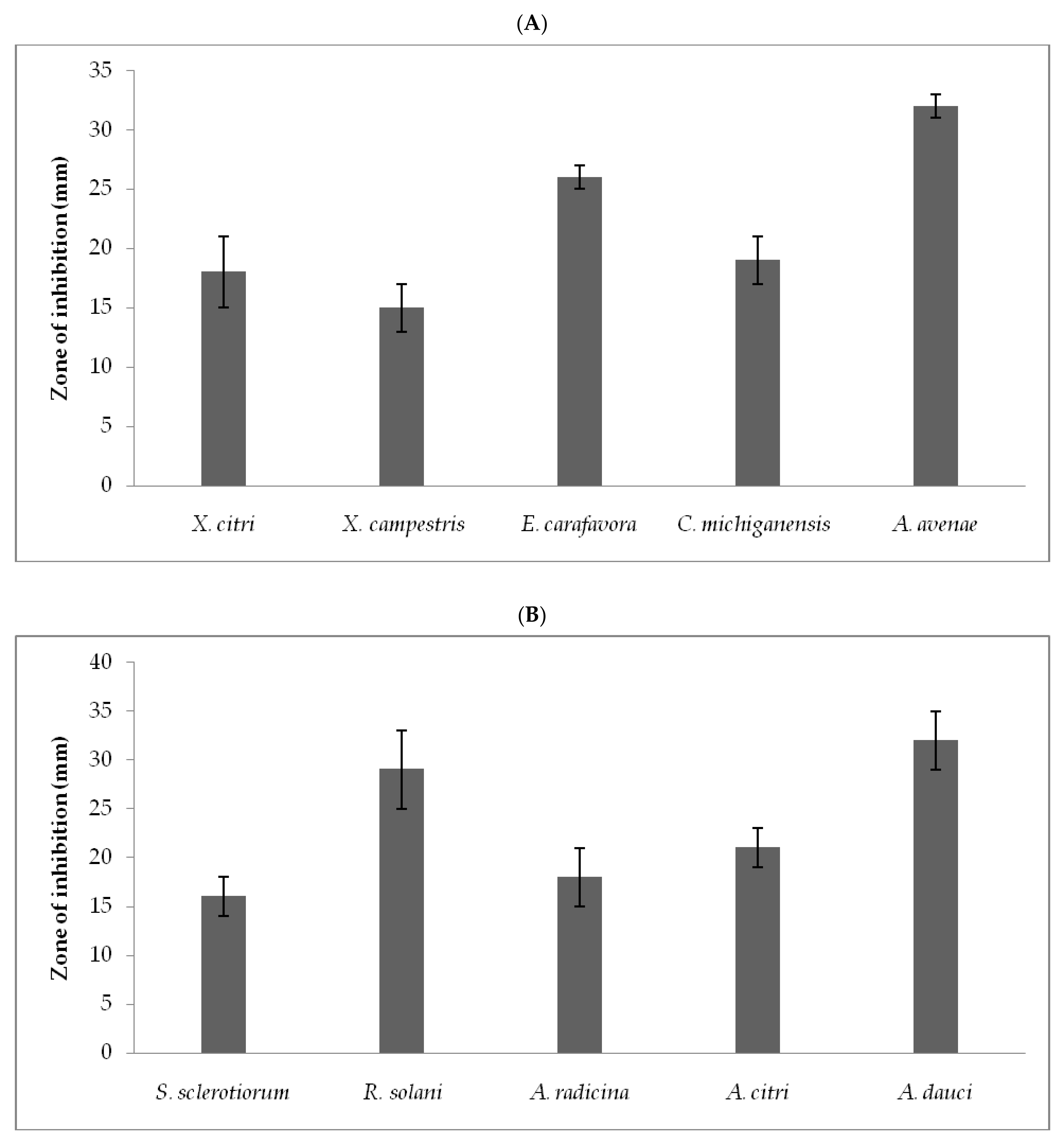

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity of Crude Extract against Phytopathogens

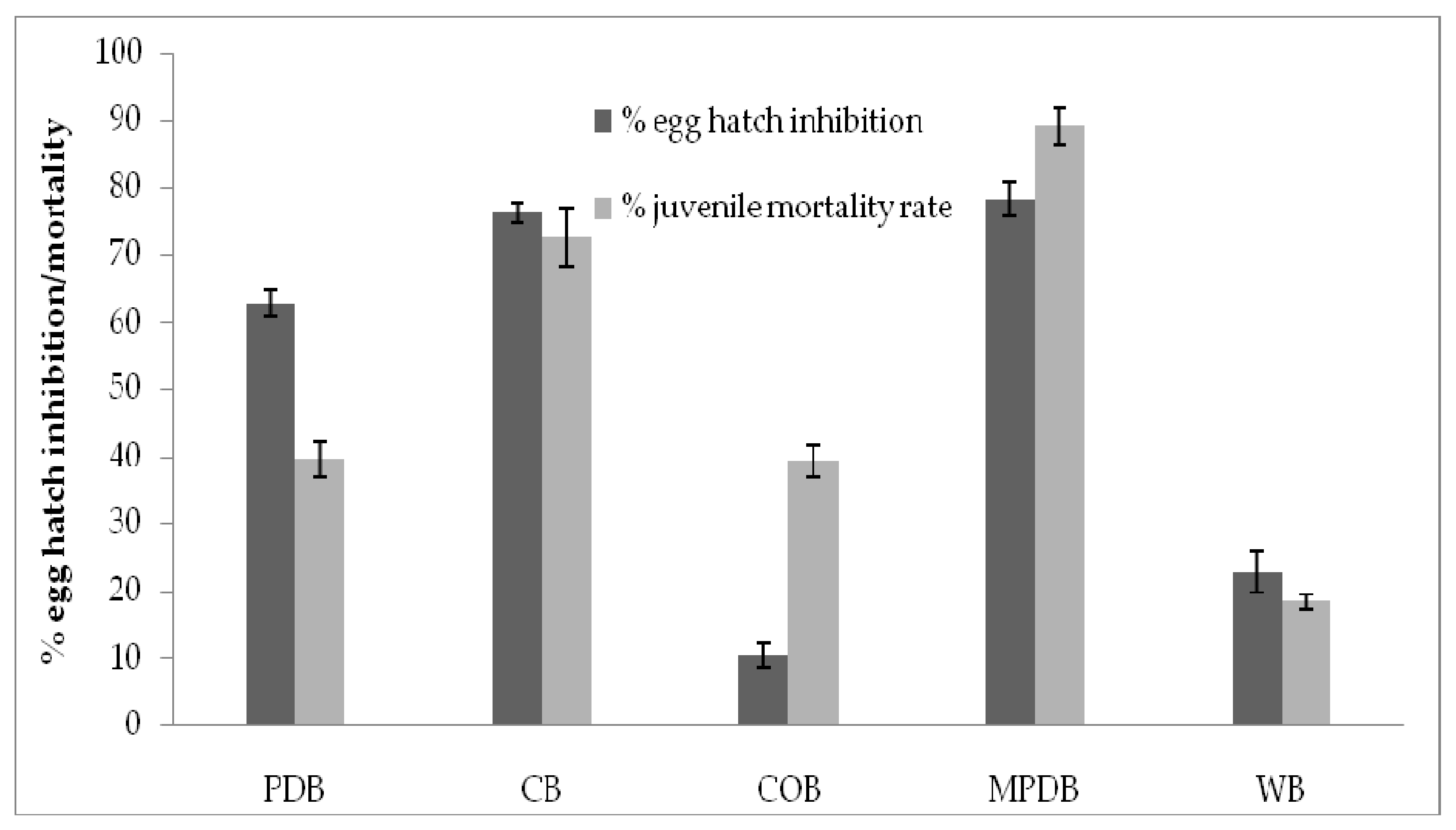

3.3. Nematicidal Activity of Secondary Metabolites of T. hamatum FB10

3.4. Extracellular Enzyme Activities

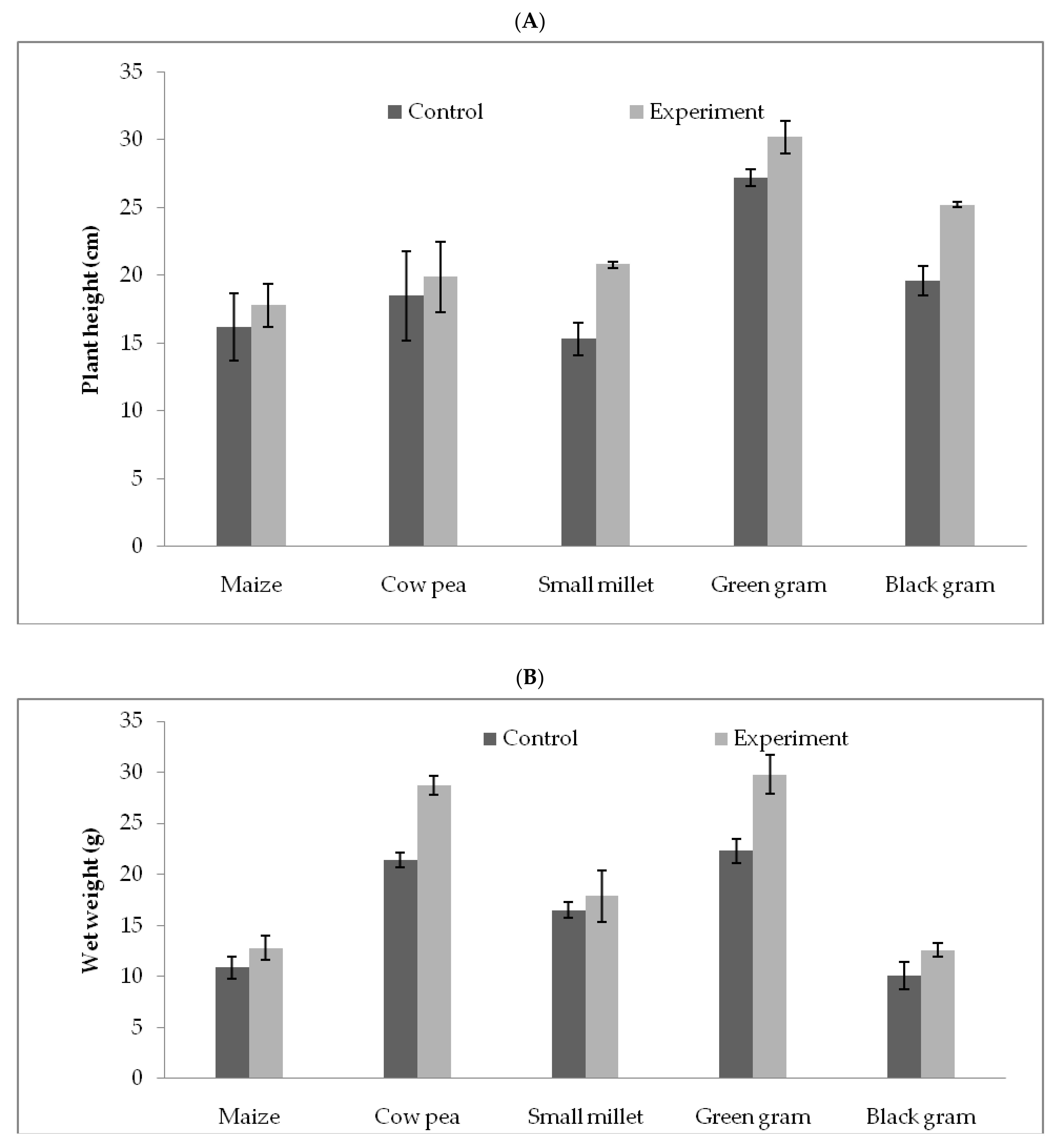

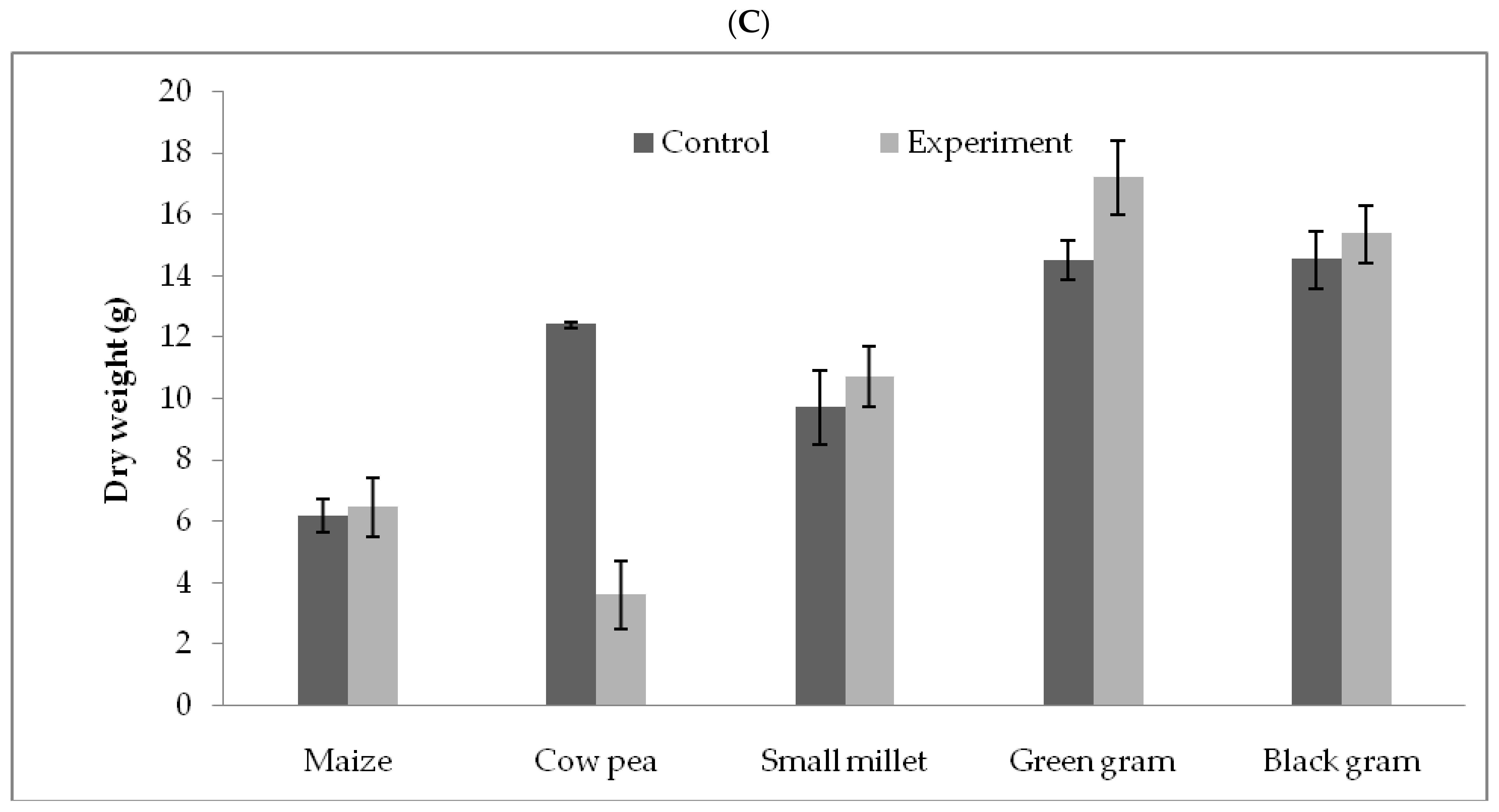

3.5. T. hamatum FB10 and Its Growth Promoting Activity

3.6. Influence of T. hamatum FB10 on Enzyme Activity of Soil

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evidente, A.; Abouzeid, M.A.; Andolfi, A.; Cimmino, A. Recent achievements in the bio-control of Orobanche infesting important crops in the Mediterranean basin. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2011, 1, 461–483. [Google Scholar]

- Cimmino, A.; Masi, M.; Evidente, M.; Superchi, S.; Evidente, A. Fungal phytotoxins with potential herbicidal activity: Chemical and biological characterization. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 1629–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrone, P.G. Pesticidal natural products–status and future potential. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.T.; Xue, Y.R.; Liu, C.H. A brief review of bioactive metabolites derived from deep-sea fungi. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 4594–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscetto, E.; Masi, M.; Esposito, M.; Di Lecce, R.; Delicato, A.; Maddau, L.; Calabrò, V.; Evidente, A.; Catania, M.R. Anti-biofilm activity of the fungal phytotoxin sphaeropsidin A against clinical isolates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Toxins 2020, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Nocera, P.; Reveglia, P.; Cimmino, A.; Evidente, A. Fungal Metabolites Antagonists towards Plant Pests and Human Pathogens: Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 834. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.; Ansari, M.I.; Ahmad, A.; Mishra, M. Major bioactive metabolites from marine fungi: A Review. Bioinformation 2015, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveglia, P.; Cimmino, A.; Masi, M.; Nocera, P.; Berova, N.; Ellestad, G.; Evidente, A. Pimarane diterpenes: Natural source, stereochemical configuration, and biological activity. Chirality 2018, 30, 1115–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, A.M.; Błazejak, S.; Kieliszek, M.; Gientka, I.; Brys, J.; Reczek, L.; Pobiega, K. Effect of exogenous stress factors on the biosynthesis of carotenoids and lipids by Rhodotorula yeast strains in media containing agro-industrial waste. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveglia, P.; Masi, M.; Evidente, A. Melleins—Intriguing natural compounds. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, J.L.; Gurian-Sherman, D. Diversity of the Burkholderiacepaciacomplexand implications for risk assessment of biological control strains. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2001, 39, 225–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardson, B. Biological substitutes for pesticides. Trends Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; Defago, G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Vlami, M.; de Sou, J.T. Antibiotic production by bacterial biocontrol agents. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2002, 81, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstrom, S. Characteristics of bacteria from oil seed rape in relation to their biocontrol of activity against Verticillium dahlia. J. Phytopathol. 2001, 149, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, R.E. The consequences of volatile organic compound mediated bacterial and fungal interactions. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2002, 81, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalchli, H.; Hormazabal, E.; Becerra, J.; Birkett, M.; Alvear, M.; Vidal, J.; Quiroz, A. Antifungal activity of volatile metabolites emitted by mycelial cultures of saprophytic fungi. J. Chem. Ecol. 2011, 27, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Innes, C.M.J.; Allan, E.J. The potential biocontrol agent Pseudomonas antimicrobica inhibits germination of conidia and outgrowth of Botrytis cinerea. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 32, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altindag, M.; Sahin, M.; Esitken, A.; Ercisli, S.; Guleryuz, M.; Donmez, M.F.; Sahin, F. Biological control of brown rot (Monilinialaxa Er.) on apricot (Prunus armeniaca L. cv. Hacihaliloglu) by Bacillus, Burkholderia, and Pseudomonas application under in vitro and in vivo conditions. Biol. Control 2006, 38, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.P.; Young, J.M. Biocidal activity in plant pathogenic Acidovorax, Burkholderia, Herbaspirillum, Ralstonia and Xanthomonas spp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 84, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijakli, M.W.; Lepoivre, P. Characterization of an exo-beta-1,3-glucanase produced by Pichia anomala strain K, antagonist of Botrytis cinereaon apples. Phytophatology 1998, 88, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saligkarias, I.D.; Gravanis, F.T.; Harry, A.S. Biological control of Botrytis cinereaon tomato plants by the use of epiphytic yeasts Candida guilliermondii strains 101 and US 7 and Candida oleophilastrain I-182: II. A study on mode of action. Biol. Control 2002, 25, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fravel, D.R. Commercialization and Implementation of Biocontrol. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Howell, C.R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma Species—Opportunistic, Avirulent Plant Symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhl, J.; Kolnaar, R.; Ravensberg, W.J. Mode of Action of Microbial Biological Control Agents against Plant Diseases: Relevance beyond E_cacy. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Asensio, D.; Tholl, D.; Wenke, K.; Rosenkranz, M.; Piechulla, B.; Schnitzler, J.P. Biogenic Volatile Emissions from the Soil. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1866–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, P.; Vincent, S.G.P. A simple method for the detection of protease activity on agar plates using bromocresolgreen dye. J. Biochem. Technol. 2013, 4, 628–630. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan, P.; Arun, A.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Vincent, S.G.P.; Arasu, M.V.; Choi, K.C. Novel Bacillus subtilis IND19 cell factory for the simultaneous production of carboxy methyl cellulase and protease using cow dung substrate in solid-substrate fermentation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.; Daisy, B. Bioprospecting for microbial endophytes and their natural products. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.H.; Debbab, A.; Kjer, J.; Proksch, P. Fungal endophytes fromhigher plants: A prolific source of phytochemicals and other bioactive natural products. Fungal Divers. 2010, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusari, S.; Pandey, S.P.; Spiteller, M. Untapped mutualisticparadigms linking host plant and endophytic fungal production ofsimilar bioactive secondary metabolites. Phytochemistry 2013, 91, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiquee, S.; Cheong, B.E.; Taslima, K.; Kausar, H.; Hasan, M.M. Separation and identification of volatile compounds from liquid cultures of Trichoderma harzianum by GC-MS using three different capillary columns. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2012, 50, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmyanova, L.I.; Teomashko, N.N.; Terentyeva, E.O.; Ruzieva, D.M.; Sattarova, R.S.; Azimova, S.S.; Gulyamova, T.G. Cytotoxic activity of fungal endophytes from Vinca, L. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2015, 4, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y.; Huang, L.L.; Ye, Y.H.; Zou, W.X.; Guo, Z.J.; Tan, R.X. Antifungal and new metabolites of Myrothecium sp. Z16, a fungus associated with white croaker Argyromosumargentatus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 100, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, M.M.; Clardy, J. Two new roridins isolated from Myrothecium sp. J. Antibiot. 2001, 54, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Tamez, P.A.; Aydogmus, Z.; Tan, G.T.; Saikawa, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Nakata, M.; Van Hung, N.; Xuan, L.T.; Cuong, N.M.; et al. Antimalarial agents from plants. III. Trichothecenes from Ficus fistulosa and Rhaphidophoradecursiva. Planta Med. 2002, 68, 1088–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.S.; Li, G.H.; Zhao, P.J.; Zheng, X.; Luo, S.L.; Li, L.; Niu, X.M.; Zhang, K.Q. Nematicidal activity of Trichoderma spp. and isolation of an active compound. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 2297–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reino, J.L.; Guerrero, R.F.; Hernandez-Galan, R.; Collado, I.G. Secondary metabolites from species of the biocontrol agent Trichoderma. Phytochem. Rev. 2008, 7, 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.A. Endophytes as sources of bioactive products. Microbes Infect. 2003, 5, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.P.; Halim, A.F. Characterization of the major aroma constituent of the fungus Trichoderma virens (Pers.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1972, 20, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Woo, S.L.; Nigro, M.; Marra, R.; Lombardi, N.; Pascale, A.; Ruocco, M.; Lanzuise, S. Trichoderma secondary metabolites active on plants and fungal pathogens. Open Mycol. J. 2014, 8 (Suppl. 1), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Yu, N.H.; Jeon, S.J.; Lee, H.W.; Bae, C.H.; Yeo, J.H.; Lee, H.B.; Kim, I.-S.; Park, H.W.; Kim, J.-C. Antibacterial activities of penicillic acid isolated from Aspergillus persii against various plant pathogenic bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 62, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błaszczyk, L.; Siwulski, M.; Sobieralski, K.; Lisiecka, J.; Jedryczka, M. Trichoderma spp.—Application and prospects for use in organic farming and industry. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2014, 54, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.; Kapoor, D.; Kumar, V.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Landi, M.; Araniti, F.; Sharma, A. Trichoderma: The “Secrets” of a Multitalented Biocontrol Agent. Plants 2020, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Maddau, L.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Scanu, B.; Evidente, A.; Cimmino, A. Bioactive metabolites from pathogenic and endophytic fungi of forest trees. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 208–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabouvette, C.; Olivain, C.; Migheli, Q.; Steinberg, C. Microbiological control of soil-borne phytopathogenic fungi with special emphasis on wilt-inducing Fusarium oxysporum. New Phytol. 2009, 184, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.N.; Ashraf, A. Trichoderma: A Potential Biocontrol Agent for Soilborne Fungal Pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 2, 22–24. Available online: https://journals.psmpublishers.org/index.php/ijmm (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Popiel, D.; Kwa′sna, H.; Chełkowski, J.; Stepien, L.; Laskowska, M. Impact of selected antagonistic fungi on Fusarium species—Toxigenic cereal pathogens. Acta Mycol. 2008, 43, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gveroska, B.; Ziberoski, J. Trichoderma harzianum as a biocontrol agent against Alternaria alternata on tobacco. Appl. Technol. Innov. 2012, 7, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberti, R.; Bergonzoni, F.; Finestrelli, A.; Leonardi, P. Biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani disease and biostimulant effect by microbial products on bean plants. Micol. Italiana 2015, 44, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Marraiki, N.; Vijayaraghavan, P.; Elgorban, A.M.; Dhas, D.D.; Al-Rashed, S.; Yassin, M.T. Low cost feedstock for the production of endoglucanase in solid state fermentation by Trichoderma hamatum NGL1 using response surface methodology and saccharification efficacy. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 1718–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Ilavenil, S.; Devanesan, S.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Choi, K.C.; Vijayaraghavan, P.; Alfuraydi, A.A.; Alanazi, N.F. Essential oils of two medicinal plants and protective properties of jack fruits against the spoilage bacteria and fungi. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 147, 112239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malar, T.J.; Antonyswamy, J.; Vijayaraghavan, P.; Kim, Y.O.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Elshikh, M.S.; Hatamleh, A.A.; Al-Dosary, M.A.; Na, S.W.; Kim, H.J. In-vitro phytochemical and pharmacological bio-efficacy studies on Azadirachta indica A. Juss and Melia azedarach Linn for anticancer activity. Saud. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, C.R.; Hanson, L.E.; Stipanovic, R.D. Induction of terpenoid synthesis in cotton roots and control of Rhizoctonia solani by seed treatments with Trichoderma virens. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, U.; Altintas, S. Effects of Trichoderma harzianum on the yield and fruit quality of tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum) grown in an unheated greenhouse. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2006, 46, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Ran, W.; Shen, Q.; Yang, X. Trichoderma harzianum strain SQR-T37 and its bio-organic fertilizer could control Rhizoctonia solani damping-off disease in cucumber seedlings mainly by the mycoparasitism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimiro, I.; Marchant, A.; Bhalerao, R.P.; Beeckman, T.; Dhooge, S.; Swarup, R.; Neil, G.; Inze, D.; Sandberg, G.; Pedro, P.J.; et al. Auxin Transport Promotes Arabidopsis Lateral Root Initiation. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peak No | Chemical Name | Chemical Formula | Retention Time (min) | Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Butyrolactone | C4H6O2 | 7.371 | 63.51 |

| 2 | Sulfurous acid, octyl 2-pentyl ester | C13H28O3S | 7.862 | 39.03 |

| 3 | Ethanoic acid | C2H4O2 | 7.896 | 27.07 |

| 4 | 2-butoxyethyl acetate | C8H16O3 | 14.298 | 87.02 |

| 5 | Butanoic acid, Butyl ester | C8H16O2 | 14.82 | 48.01 |

| 6 | 1-hydroxy-2- propanone | C6H6O | 15.96 | 79.66 |

| 7 | 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)phenol | C14H22O | 17.25 | 83.65 |

| 8 | 6-pentyl-alpha-pyrone | C10H14O2 | 22.03 | 67.05 |

| 9 | Hexadecanoic acid | C20H40O2 | 22.87 | 82.69 |

| 10 | 2H-pyran-2-one | C6H10O3 | 27.65 | 40.26 |

| 11 | 2,6-dimethyl-naphthalene | C12H12 | 29.97 | 70.81 |

| 12 | Hexadecane | C16H34 | 38.06 | 82.39 |

| 13 | 2-Octene | C8H16 | 49.2 | 72.7 |

| Phytopathogens | MIC (µg/mL) | MBC (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial phytopathogens | ||

| X. citri | 63 ± 2.1 | 82.5 ± 2.5 |

| X. campestris, | 32 ± 3.2 | 72.5 ± 1.25 |

| E. carafavora | 58 ± 3.5 | 89 ± 5.0 |

| C. michiganensis | 49 ± 5.5 | 92 ± 2.5 |

| A. avenae | 30 ± 2.5 | 70 ± 1.25 |

| Fungal phytopathogens | ||

| S. sclerotiorum | 63.5 ± 7.25 | 120 ± 10.5 |

| R. solani | 71 ± 3.25 | 153 ± 2.5 |

| A. radicina | 58.5 ± 3.0 | 115.5 ± 1.25 |

| A. citri | 60.5 ± 5.5 | 110.2 ± 3.75 |

| A. dauci | 65 ± 3.75 | 122.5 ± 3.0 |

| Enzymes | Activity (IU/mL) |

|---|---|

| Chitinase | 1.7 ± 0.32 |

| Protease | 476 ± 39.6 |

| Polygalacturanase | 38.5 ± 2.7 |

| Cellulase | 12.9 ± 10.1 |

| Amylase | 27.5 ± 2.9 |

| Pectinase | 0.2 ± 0.03 |

| Glucanase | 58.6 ± 2.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baazeem, A.; Almanea, A.; Manikandan, P.; Alorabi, M.; Vijayaraghavan, P.; Abdel-Hadi, A. In Vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal, Nematocidal and Growth Promoting Activities of Trichoderma hamatum FB10 and Its Secondary Metabolites. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7050331

Baazeem A, Almanea A, Manikandan P, Alorabi M, Vijayaraghavan P, Abdel-Hadi A. In Vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal, Nematocidal and Growth Promoting Activities of Trichoderma hamatum FB10 and Its Secondary Metabolites. Journal of Fungi. 2021; 7(5):331. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7050331

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaazeem, Alaa, Abdulaziz Almanea, Palanisamy Manikandan, Mohammed Alorabi, Ponnuswamy Vijayaraghavan, and Ahmed Abdel-Hadi. 2021. "In Vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal, Nematocidal and Growth Promoting Activities of Trichoderma hamatum FB10 and Its Secondary Metabolites" Journal of Fungi 7, no. 5: 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7050331

APA StyleBaazeem, A., Almanea, A., Manikandan, P., Alorabi, M., Vijayaraghavan, P., & Abdel-Hadi, A. (2021). In Vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal, Nematocidal and Growth Promoting Activities of Trichoderma hamatum FB10 and Its Secondary Metabolites. Journal of Fungi, 7(5), 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7050331