Patient Susceptibility to Candidiasis—A Potential for Adjunctive Immunotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Host Immune Defense against Candida

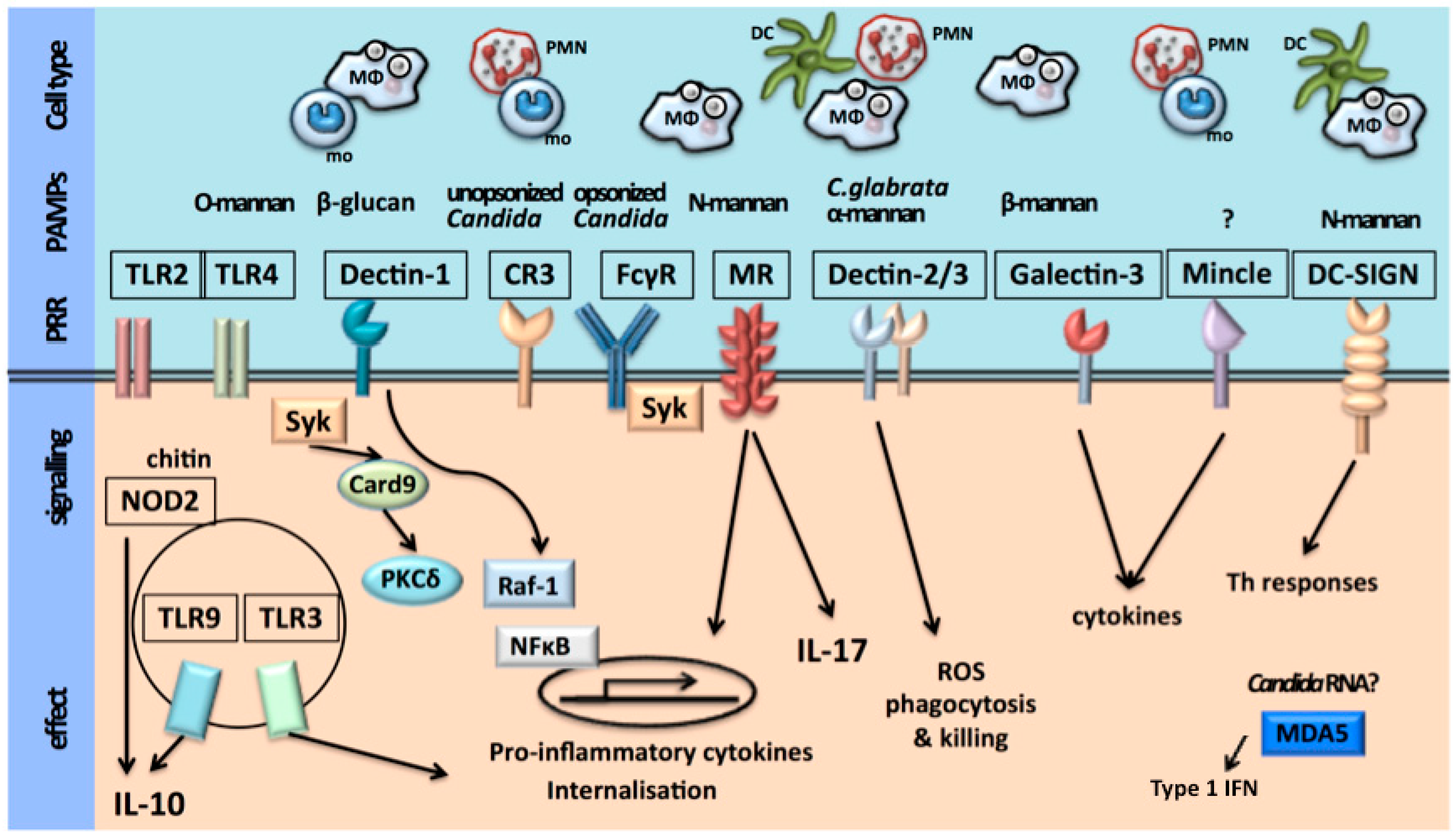

2.1. Recognition of C. albicans

2.2. Activation of Host Immune Defense

3. Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

3.1. Epithelial Function

3.2. Th17 Pathway

3.3. Genetic Susceptibility to Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

3.3.1. Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis (CMC)

3.3.2. Hyper IgE Syndrome (HIES)

3.3.3. Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (RVVC)

3.3.4. Candida Colonization, Cutaneous Candidiasis and Onychomycosis

4. Invasive Candidiasis

4.1. Th1 Pathway and Neutrophil Function

4.2. Genetic Susceptibility to Invasive Candidiasis

4.2.1. Increased Susceptibility to Acquire Candidemia

4.2.2. Increased Susceptibility to Persistent Candidemia

4.2.3. Increased Susceptibility to Candida Dissemination

5. Translating Knowledge into Clinical Practice

5.1. Prophylaxis

5.2. Immunostimulatory Therapy

5.2.1. Recombinant Cytokine Therapy

5.2.2. Vaccination and Antibodies

5.2.3. Innate Cellular Immunotherapy

5.3. Immunosuppressive Therapy

5.4. Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smeekens, S.P.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Kullberg, B.J.; Netea, M.G. Genetic susceptibility to Candida infections. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Plantinga, T.S.; Hoischen, A.; Smeekens, S.P.; Joosten, L.A.; Gilissen, C.; Arts, P.; Rosentul, D.C.; Carmichael, A.J.; Smits-van der Graaf, C.A.; et al. STAT1 mutations in autosomal dominant chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullberg, B.J.; Arendrup, M.C. Invasive Candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullberg, B.J.; van de Veerdonk, F.; Netea, M.G. Immunotherapy: A potential adjunctive treatment for fungal infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 27, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Brown, G.D.; Kullberg, B.J.; Gow, N.A. An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Kullberg, B.J.; van de Veerdonk, F.L. Immune defence against Candida fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Cao, Y.; Yan, T. Innate immune cell response upon Candida albicans infection. Virulence 2016, 7, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, N.A.; Hube, B. Importance of the Candida albicans cell wall during commensalism and infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, R.A.; Gow, N.A. Mannosylation in Candida albicans: Role in cell wall function and immune recognition. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 90, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, J.F.; Prill, S.K. O-glycosylation. Med. Mycol. 2001, 39 (Suppl. S1), 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, J.E. N-glycosylation of yeast, with emphasis on Candida albicans. Med. Mycol. 2001, 39 (Suppl. S1), 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klis, F.M.; Boorsma, A.; de Groot, P.W. Cell wall construction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2006, 23, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, N.; Suzuki, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Okawa, Y. Chemical structure of the cell-wall mannan of Candida albicans serotype A and its difference in yeast and hyphal forms. Biochem. J. 2007, 404, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowman, D.W.; Greene, R.R.; Bearden, D.W.; Kruppa, M.D.; Pottier, M.; Monteiro, M.A.; Soldatov, D.V.; Ensley, H.E.; Cheng, S.C.; Netea, M.G.; et al. Novel structural features in Candida albicans hyphal glucan provide a basis for differential innate immune recognition of hyphae versus yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3432–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, C.A.; Schofield, D.A.; Gooday, G.W.; Gow, N.A. Regulation of chitin synthesis during dimorphic growth of Candida albicans. Microbiology 1998, 144 Pt 2, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.D.; Gordon, S. Immune recognition. A new receptor for β-glucans. Nature 2001, 413, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambi, A.; Gijzen, K.; de Vries, L.J.; Torensma, R.; Joosten, B.; Adema, G.J.; Netea, M.G.; Kullberg, B.J.; Romani, L.; Figdor, C.G. The C-type lectin DC-SIGN (CD209) is an antigen-uptake receptor for Candida albicans on dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003, 33, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouault, T.; Ibata-Ombetta, S.; Takeuchi, O.; Trinel, P.A.; Sacchetti, P.; Lefebvre, P.; Akira, S.; Poulain, D. Candida albicans phospholipomannan is sensed through toll-like receptors. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 188, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Gow, N.A.; Munro, C.A.; Bates, S.; Collins, C.; Ferwerda, G.; Hobson, R.P.; Bertram, G.; Hughes, H.B.; Jansen, T.; et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantner, B.N.; Simmons, R.M.; Underhill, D.M. Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wileman, T.E.; Lennartz, M.R.; Stahl, P.D. Identification of the macrophage mannose receptor as a 175-kDa membrane protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 2501–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, J.D.; Shepherd, V.L. Purification of the human alveolar macrophage mannose receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987, 148, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.D.; Gordon, S. Fungal β-glucans and mammalian immunity. Immunity 2003, 19, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambi, A.; Netea, M.G.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Gow, N.A.; Hato, S.V.; Lowman, D.W.; Kullberg, B.J.; Torensma, R.; Williams, D.L.; Figdor, C.G. Dendritic cell interaction with Candida albicans critically depends on N-linked mannan. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 20590–20599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodridge, H.S.; Reyes, C.N.; Becker, C.A.; Katsumoto, T.R.; Ma, J.; Wolf, A.J.; Bose, N.; Chan, A.S.; Magee, A.S.; Danielson, M.E.; et al. Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse’. Nature 2011, 472, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.D.; Taylor, P.R.; Reid, D.M.; Willment, J.A.; Williams, D.L.; Martinez-Pomares, L.; Wong, S.Y.; Gordon, S. Dectin-1 is a major beta-glucan receptor on macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, R.A.; Brown, G.D. The role of Dectin-1 in the host defence against fungal infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, C.A.; Salvage-Jones, J.A.; Li, X.; Hitchens, K.; Butcher, S.; Murray, R.Z.; Beckhouse, A.G.; Lo, Y.L.; Manzanero, S.; Cobbold, C.; et al. The macrophage-inducible C-type lectin, mincle, is an essential component of the innate immune response to Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 7404–7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, M.; van der Lee, R.; Cheng, S.C.; Johnson, M.D.; Kumar, V.; Ng, A.; Plantinga, T.S.; Smeekens, S.P.; Oosting, M.; Wang, X.; et al. The RIG-I-like helicase receptor MDA5 (IFIH1) is involved in the host defense against Candida infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, M.; Carvalho, A.; Cunha, C.; Plantinga, T.S.; van de Veerdonk, F.; Puccetti, M.; Galosi, C.; Joosten, L.A.; Dupont, B.; Kullberg, B.J.; et al. Association of a variable number tandem repeat in the NLRP3 gene in women with susceptibility to RVVC. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeekens, S.P.; Ng, A.; Kumar, V.; Johnson, M.D.; Plantinga, T.S.; van Diemen, C.; Arts, P.; Verwiel, E.T.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Fransen, K.; et al. Functional genomics identifies type I interferon pathway as central for host defense against Candida albicans. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinsbroek, S.E.; Taylor, P.R.; Martinez, F.O.; Martinez-Pomares, L.; Brown, G.D.; Gordon, S. Stage-specific sampling by pattern recognition receptors during Candida albicans phagocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudkin, F.M.; Bain, J.M.; Walls, C.; Lewis, L.E.; Gow, N.A.; Erwig, L.P. Altered dynamics of Candida albicans phagocytosis by macrophages and PMNs when both phagocyte subsets are present. mBio 2013, 4, e00810–e00813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, C.F.; Ermert, D.; Schmid, M.; Abu-Abed, U.; Goosmann, C.; Nacken, W.; Brinkmann, V.; Jungblut, P.R.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miramon, P.; Dunker, C.; Windecker, H.; Bohovych, I.M.; Brown, A.J.; Kurzai, O.; Hube, B. Cellular responses of Candida albicans to phagocytosis and the extracellular activities of neutrophils are critical to counteract carbohydrate starvation, oxidative and nitrosative stress. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantner, B.N.; Simmons, R.M.; Canavera, S.J.; Akira, S.; Underhill, D.M. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll-like receptor 2. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herre, J.; Marshall, A.S.; Caron, E.; Edwards, A.D.; Williams, D.L.; Schweighoffer, E.; Tybulewicz, V.; Reis e Sousa, C.; Gordon, S.; Brown, G.D. Dectin-1 uses novel mechanisms for yeast phagocytosis in macrophages. Blood 2004, 104, 4038–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, A.D.; Willment, J.A.; Dorward, D.W.; Williams, D.L.; Brown, G.D.; DeLeo, F.R. Dectin-1 promotes fungicidal activity of human neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007, 37, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, M.K.; Levitz, S.M. Interactions of fungi with phagocytes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2002, 5, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E.P.; Lu, H.; Jacobs, H.L.; Messina, C.G.; Bolsover, S.; Gabella, G.; Potma, E.O.; Warley, A.; Roes, J.; Segal, A.W. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature 2002, 416, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, L.; Martinon, F.; Burns, K.; McDermott, M.F.; Hawkins, P.N.; Tschopp, J. NALP3 forms an IL-1β-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity 2004, 20, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hise, A.G.; Tomalka, J.; Ganesan, S.; Patel, K.; Hall, B.A.; Brown, G.D.; Fitzgerald, K.A. An essential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.C.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Lenardon, M.; Stoffels, M.; Plantinga, T.; Smeekens, S.; Rizzetto, L.; Mukaremera, L.; Preechasuth, K.; Cavalieri, D.; et al. The dectin-1/inflammasome pathway is responsible for the induction of protective T-helper 17 responses that discriminate between yeasts and hyphae of Candida albicans. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 90, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalor, S.J.; Dungan, L.S.; Sutton, C.E.; Basdeo, S.A.; Fletcher, J.M.; Mills, K.H. Caspase-1-processed cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 promote IL-17 production by gammadelta and CD4 T cells that mediate autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 5738–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Joosten, L.A.; Shaw, P.J.; Smeekens, S.P.; Malireddi, R.K.; van der Meer, J.W.; Kullberg, B.J.; Netea, M.G.; Kanneganti, T.D. The inflammasome drives protective Th1 and Th17 cellular responses in disseminated candidiasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 2260–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyerich, S.; Wagener, J.; Wenzel, V.; Scarponi, C.; Pennino, D.; Albanesi, C.; Schaller, M.; Behrendt, H.; Ring, J.; Schmidt-Weber, C.B.; et al. IL-22 and TNF-α represent a key cytokine combination for epidermal integrity during infection with Candida albicans. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 1894–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, C.E.; Mele, F.; Aschenbrenner, D.; Jarrossay, D.; Ronchi, F.; Gattorno, M.; Monticelli, S.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F. Pathogen-induced human TH17 cells produce IFN-γ or IL-10 and are regulated by IL-1β. Nature 2012, 484, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaby, M.R.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Rinderknecht, E.; Svedersky, L.P.; Finkle, B.S.; Palladino, M.A., Jr. Activation of human polymorphonuclear neutrophil functions by interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factors. J. Immunol. 1985, 135, 2069–2073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nathan, C.F.; Murray, H.W.; Wiebe, M.E.; Rubin, B.Y. Identification of interferon-γ as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J. Exp. Med. 1983, 158, 670–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.C.; Tan, X.Y.; Luxenberg, D.P.; Karim, R.; Dunussi-Joannopoulos, K.; Collins, M.; Fouser, L.A. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 2271–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Na, L.; Fidel, P.L.; Schwarzenberger, P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 190, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeekens, S.P.; Huttenhower, C.; Riza, A.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Zeeuwen, P.L.; Schalkwijk, J.; van der Meer, J.W.; Xavier, R.J.; Netea, M.G.; Gevers, D. Skin microbiome imbalance in patients with STAT1/STAT3 defects impairs innate host defense responses. J. Innate Immun. 2014, 6, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oever, J.T.; Netea, M.G. The bacteriome-mycobiome interaction and antifungal host defense. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 3182–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdugo, F.; Laksmana, T.; Uribarri, A. Systemic antibiotics and the risk of superinfection in peri-implantitis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2016, 64, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, A.; Edlund, C.; Nord, C.E. Effect of antimicrobial agents on the ecological balance of human microflora. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2001, 1, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Schwartz, K.; Bartoces, M.; Monsur, J.; Severson, R.K.; Sobel, J.D. Effect of antibiotics on vulvovaginal candidiasis: A MetroNet study. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2008, 21, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, B.; Ferreira, C.; Alves, C.T.; Henriques, M.; Azeredo, J.; Silva, S. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 905–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellepola, A.N.; Samaranayake, L.P. Inhalational and topical steroids, and oral candidosis: A mini review. Oral Dis. 2001, 7, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunther, L.S.; Martins, H.P.; Gimenes, F.; Abreu, A.L.; Consolaro, M.E.; Svidzinski, T.I. Prevalence of Candida albicans and non-albicans isolates from vaginal secretions: Comparative evaluation of colonization, vaginal candidiasis and recurrent vaginal candidiasis in diabetic and non-diabetic women. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2014, 132, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boven, J.F.; de Jong-van den Berg, L.T.; Vegter, S. Inhaled corticosteroids and the occurrence of oral candidiasis: A prescription sequence symmetry analysis. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadian, H.; Yassaei, S.; Bouzarjomehri, F.; Ghaffari Targhi, M.; Kheirollahi, K. Oral Complications of The Oromaxillofacial Area Radiotherapy. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wulandari, E.A.T.; Saraswati, H.; Adawiyah, R.; Djauzi, S.; Wahyuningsih, R.; Price, P. Immunological and epidemiological factors affecting candidiasis in HIV patients beginning antiretroviral therapy in an Asian clinic. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 82, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyes, D.L.; Wilson, D.; Richardson, J.P.; Mogavero, S.; Tang, S.X.; Wernecke, J.; Hofs, S.; Gratacap, R.L.; Robbins, J.; Runglall, M.; et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature 2016, 532, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Marijnissen, R.J.; Kullberg, B.J.; Koenen, H.J.; Cheng, S.C.; Joosten, I.; van den Berg, W.B.; Williams, D.L.; van der Meer, J.W.; Joosten, L.A.; et al. The macrophage mannose receptor induces IL-17 in response to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, H.R.; Gaffen, S.L. IL-17-Mediated Immunity to the Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, N.A.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Brown, A.J.; Netea, M.G. Candida albicans morphogenesis and host defence: Discriminating invasion from colonization. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 10, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladiator, A.; Wangler, N.; Trautwein-Weidner, K.; LeibundGut-Landmann, S. Cutting edge: IL-17-secreting innate lymphoid cells are essential for host defense against fungal infection. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weindl, G.; Wagener, J.; Schaller, M. Epithelial cells and innate antifungal defense. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weindl, G.; Naglik, J.R.; Kaesler, S.; Biedermann, T.; Hube, B.; Korting, H.C.; Schaller, M. Human epithelial cells establish direct antifungal defense through TLR4-mediated signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3664–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.C.; Joosten, L.A.; Kullberg, B.J.; Netea, M.G. Interplay between Candida albicans and the mammalian innate host defense. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparber, F.; LeibundGut-Landmann, S. Interleukin 17-Mediated Host Defense against Candida albicans. Pathogens 2015, 4, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puel, A.; Cypowyj, S.; Bustamante, J.; Wright, J.F.; Liu, L.; Lim, H.K.; Migaud, M.; Israel, L.; Chrabieh, M.; Audry, M.; et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science 2011, 332, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltesz, B.; Toth, B.; Sarkadi, A.K.; Erdos, M.; Marodi, L. The Evolving View of IL-17-Mediated Immunity in Defense Against Mucocutaneous Candidiasis in Humans. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 34, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, S.; Puel, A.; Casanova, J.L.; Kobayashi, M. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis disease associated with inborn errors of IL-17 immunity. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2016, 5, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Santos, N.; Huppler, A.R.; Peterson, A.C.; Khader, S.A.; McKenna, K.C.; Gaffen, S.L. Th17 cells confer long-term adaptive immunity to oral mucosal Candida albicans infections. Mucosal Immunol. 2013, 6, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppler, A.R.; Conti, H.R.; Hernandez-Santos, N.; Darville, T.; Biswas, P.S.; Gaffen, S.L. Role of neutrophils in IL-17-dependent immunity to mucosal candidiasis. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyerich, K.; Dimartino, V.; Cavani, A. IL-17 and IL-22 in immunity: Driving protection and pathology. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017, 47, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolls, J.K. Th17 cells in mucosal immunity and tissue inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2010, 32, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, B.R.; Craft, J. Barrier immunity and IL-17. Semin. Immunol. 2009, 21, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Khader, S. Yin and yang of interleukin-17 in host immunity to infection. F1000Res 2017, 6, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomalka, J.; Azodi, E.; Narra, H.P.; Patel, K.; O’Neill, S.; Cardwell, C.; Hall, B.A.; Wilson, J.M.; Hise, A.G. Beta-Defensin 1 plays a role in acute mucosal defense against Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 1788–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, R.M.; Gaffen, S.L. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: Mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology 2010, 129, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, H.R.; Shen, F.; Nayyar, N.; Stocum, E.; Sun, J.N.; Lindemann, M.J.; Ho, A.W.; Hai, J.H.; Yu, J.J.; Jung, J.W.; et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautwein-Weidner, K.; Gladiator, A.; Nur, S.; Diethelm, P.; LeibundGut-Landmann, S. IL-17-mediated antifungal defense in the oral mucosa is independent of neutrophils. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Malki, K.; Karbach, S.H.; Huppert, J.; Zayoud, M.; Reissig, S.; Schuler, R.; Nikolaev, A.; Karram, K.; Munzel, T.; Kuhlmann, C.R.; et al. An alternative pathway of imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in the absence of interleukin-17 receptor a signaling. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, J.; Kolls, J.K.; Happel, K.I.; Wormley, F.; Wozniak, K.L.; Fidel, P.L., Jr. The acute neutrophil response mediated by S100 alarmins during vaginal Candida infections is independent of the Th17-pathway. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, S.M.; DeLeo, F.R.; Elloumi, H.Z.; Hsu, A.P.; Uzel, G.; Brodsky, N.; Freeman, A.F.; Demidowich, A.; Davis, J.; Turner, M.L.; et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.D. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puel, A.; Doffinger, R.; Natividad, A.; Chrabieh, M.; Barcenas-Morales, G.; Picard, C.; Cobat, A.; Ouachee-Chardin, M.; Toulon, A.; Bustamante, J.; et al. Autoantibodies against IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorses, P.; Aaltonen, J.; Horelli-Kuitunen, N.; Yaspo, M.L.; Peltonen, L. Gene defect behind APECED: A new clue to autoimmunity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998, 7, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagamine, K.; Peterson, P.; Scott, H.S.; Kudoh, J.; Minoshima, S.; Heino, M.; Krohn, K.J.; Lalioti, M.D.; Mullis, P.E.; Antonarakis, S.E.; et al. Positional cloning of the APECED gene. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahonen, P.; Myllarniemi, S.; Sipila, I.; Perheentupa, J. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferre, E.M.; Rose, S.R.; Rosenzweig, S.D.; Burbelo, P.D.; Romito, K.R.; Niemela, J.E.; Rosen, L.B.; Break, T.J.; Gu, W.; Hunsberger, S.; et al. Redefined clinical features and diagnostic criteria in autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e88782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meesilpavikkai, K.; Dik, W.A.; Schrijver, B.; Nagtzaam, N.M.; van Rijswijk, A.; Driessen, G.J.; van der Spek, P.J.; van Hagen, P.M.; Dalm, V.A. A Novel Heterozygous Mutation in the STAT1 SH2 Domain Causes Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis, Atypically Diverse Infections, Autoimmunity, and Impaired Cytokine Regulation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toubiana, J.; Okada, S.; Hiller, J.; Oleastro, M.; Lagos Gomez, M.; Aldave Becerra, J.C.; Ouachee-Chardin, M.; Fouyssac, F.; Girisha, K.M.; Etzioni, A.; et al. Heterozygous STAT1 gain-of-function mutations underlie an unexpectedly broad clinical phenotype. Blood 2016, 127, 3154–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadak, M.; Jacobs, R.; Skuljec, J.; Jirmo, A.C.; Yildiz, O.; Donnerstag, F.; Baerlecken, N.T.; Schmidt, R.E.; Lanfermann, H.; Skripuletz, T.; et al. Gain-of-function STAT1 mutations are associated with intracranial aneurysms. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 178, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puel, A.; Cypowyj, S.; Marodi, L.; Abel, L.; Picard, C.; Casanova, J.L. Inborn errors of human IL-17 immunity underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 12, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K.L.; Rosler, B.; Wang, X.; Lachmandas, E.; Kamsteeg, M.; Jacobs, C.W.; Joosten, L.A.; Netea, M.G.; van de Veerdonk, F.L. Th2 and Th9 responses in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and hyper-IgE syndrome. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2016, 46, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosentul, D.C.; Delsing, C.E.; Jaeger, M.; Plantinga, T.S.; Oosting, M.; Costantini, I.; Venselaar, H.; Joosten, L.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Dupont, B.; et al. Gene polymorphisms in pattern recognition receptors and susceptibility to idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babula, O.; Lazdane, G.; Kroica, J.; Ledger, W.J.; Witkin, S.S. Relation between recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, vaginal concentrations of mannose-binding lectin, and a mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphism in Latvian women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo, P.C.; Babula, O.; Goncalves, A.K.; Linhares, I.M.; Amaral, R.L.; Ledger, W.J.; Witkin, S.S. Mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphism, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and bacterial vaginosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 109, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babula, O.; Lazdane, G.; Kroica, J.; Linhares, I.M.; Ledger, W.J.; Witkin, S.S. Frequency of interleukin-4 (IL-4) -589 gene polymorphism and vaginal concentrations of IL-4, nitric oxide, and mannose-binding lectin in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plantinga, T.S.; van der Velden, W.J.; Ferwerda, B.; van Spriel, A.B.; Adema, G.; Feuth, T.; Donnelly, J.P.; Brown, G.D.; Kullberg, B.J.; Blijlevens, N.M.; et al. Early stop polymorphism in human DECTIN-1 is associated with increased candida colonization in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferwerda, B.; Ferwerda, G.; Plantinga, T.S.; Willment, J.A.; van Spriel, A.B.; Venselaar, H.; Elbers, C.C.; Johnson, M.D.; Cambi, A.; Huysamen, C.; et al. Human dectin-1 deficiency and mucocutaneous fungal infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahum, A.; Dadi, H.; Bates, A.; Roifman, C.M. The biological significance of TLR3 variant, L412F, in conferring susceptibility to cutaneous candidiasis, CMV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2012, 11, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagunes, L.; Rello, J. Invasive candidiasis: From mycobiome to infection, therapy, and prevention. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullberg, B.J.; Sobel, J.D.; Ruhnke, M.; Pappas, P.G.; Viscoli, C.; Rex, J.H.; Cleary, J.D.; Rubinstein, E.; Church, L.W.; Brown, J.M.; et al. Voriconazole versus a regimen of amphotericin B followed by fluconazole for candidaemia in non-neutropenic patients: A randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2005, 366, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, I.; Nightingale, P.; Patel, M.; Jumaa, P. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcome of candidemia: Experience in a tertiary referral center in the UK. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 15, e759–e763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reboli, A.C.; Rotstein, C.; Pappas, P.G.; Chapman, S.W.; Kett, D.H.; Kumar, D.; Betts, R.; Wible, M.; Goldstein, B.P.; Schranz, J.; et al. Anidulafungin versus fluconazole for invasive candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2472–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammaert, B.; Desjardins, A.; Lortholary, O. New insights into hepatosplenic candidosis, a manifestation of chronic disseminated candidosis. Mycoses 2012, 55, e74–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionakis, M.S.; Netea, M.G. Candida and host determinants of susceptibility to invasive candidiasis. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.D. Innate antifungal immunity: The key role of phagocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plantinga, T.S.; Johnson, M.D.; Scott, W.K.; van de Vosse, E.; Velez Edwards, D.R.; Smith, P.B.; Alexander, B.D.; Yang, J.C.; Kremer, D.; Laird, G.M.; et al. Toll-like receptor 1 polymorphisms increase susceptibility to candidemia. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Cheng, S.C.; Johnson, M.D.; Smeekens, S.P.; Wojtowicz, A.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.; Karjalainen, J.; Franke, L.; Withoff, S.; Plantinga, T.S.; et al. Immunochip SNP array identifies novel genetic variants conferring susceptibility to candidaemia. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzaraki, V.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Jaeger, M.; Ricano-Ponce, I.; Johnson, M.D.; Oosting, M.; Franke, L.; Withoff, S.; Perfect, J.R.; Joosten, L.A.B.; et al. An integrative genomics approach identifies novel pathways that influence candidaemia susceptibility. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.D.; Plantinga, T.S.; van de Vosse, E.; Velez Edwards, D.R.; Smith, P.B.; Alexander, B.D.; Yang, J.C.; Kremer, D.; Laird, G.M.; Oosting, M.; et al. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and the outcome of invasive candidiasis: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.H.; Foster, C.B.; Taylor, J.G.; Erichsen, H.C.; Chen, R.A.; Walsh, T.J.; Anttila, V.J.; Ruutu, T.; Palotie, A.; Chanock, S.J. Association between chronic disseminated candidiasis in adult acute leukemia and common IL4 promoter haplotypes. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 187, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glocker, E.O.; Hennigs, A.; Nabavi, M.; Schaffer, A.A.; Woellner, C.; Salzer, U.; Pfeifer, D.; Veelken, H.; Warnatz, K.; Tahami, F.; et al. A homozygous CARD9 mutation in a family with susceptibility to fungal infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewniak, A.; Gazendam, R.P.; Tool, A.T.; van Houdt, M.; Jansen, M.H.; van Hamme, J.L.; van Leeuwen, E.M.; Roos, D.; Scalais, E.; de Beaufort, C.; et al. Invasive fungal infection and impaired neutrophil killing in human CARD9 deficiency. Blood 2013, 121, 2385–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanternier, F.; Mahdaviani, S.A.; Barbati, E.; Chaussade, H.; Koumar, Y.; Levy, R.; Denis, B.; Brunel, A.S.; Martin, S.; Loop, M.; et al. Inherited CARD9 deficiency in otherwise healthy children and adults with Candida species-induced meningoencephalitis, colitis, or both. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong-James, D.; Brown, G.D.; Netea, M.G.; Zelante, T.; Gresnigt, M.S.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Levitz, S.M. Immunotherapeutic approaches to treatment of fungal diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, C.; Hart, E.; Lefort, A.; Ribaud, P.; Dromer, F.; Denning, D.W.; Lortholary, O. Fluconazole for the management of invasive candidiasis: Where do we stand after 15 years? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 384–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Shoham, S.; Vazquez, J.; Reboli, A.; Betts, R.; Barron, M.A.; Schuster, M.; Judson, M.A.; Revankar, S.G.; Caeiro, J.P.; et al. MSG-01: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of caspofungin prophylaxis followed by preemptive therapy for invasive candidiasis in high-risk adults in the critical care setting. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Kullberg, B.J. Novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of Candida infections: The potential of immunotherapy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.E.; Silva, S.; Azeredo, J.; Henriques, M. Novel strategies to fight Candida species infection. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, J.A.; Gupta, S.; Villanueva, A. Potential utility of recombinant human GM-CSF as adjunctive treatment of refractory oropharyngeal candidiasis in AIDS patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1998, 17, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, J.A.; Hidalgo, J.A.; de Bono, S. Use of sargramostim (rh-GM-CSF) as adjunctive treatment of fluconazole-refractory oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with AIDS: A pilot study. HIV Clin. Trials 2000, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graybill, J.R.; Bocanegra, R.; Luther, M. Antifungal combination therapy with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and fluconazole in experimental disseminated candidiasis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1995, 14, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullberg, B.J.; Oude Lashof, A.M.; Netea, M.G. Design of efficacy trials of cytokines in combination with antifungal drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39 (Suppl. S4), S218–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullberg, B.J.; van’t Wout, J.W.; Hoogstraten, C.; van Furth, R. Recombinant interferon-gamma enhances resistance to acute disseminated Candida albicans infection in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 168, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delsing, C.E.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Leentjens, J.; Preijers, F.; Frager, F.A.; Kox, M.; Monneret, G.; Venet, F.; Bleeker-Rovers, C.P.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; et al. Interferon-γ as adjunctive immunotherapy for invasive fungal infections: A case series. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torosantucci, A.; Bromuro, C.; Chiani, P.; de Bernardis, F.; Berti, F.; Galli, C.; Norelli, F.; Bellucci, C.; Polonelli, L.; Costantino, P.; et al. A novel glyco-conjugate vaccine against fungal pathogens. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.S.; Luo, G.; Gebremariam, T.; Lee, H.; Schmidt, C.S.; Hennessey, J.P., Jr.; French, S.W.; Yeaman, M.R.; Filler, S.G.; Edwards, J.E., Jr. NDV-3 protects mice from vulvovaginal candidiasis through T- and B-cell immune response. Vaccine 2013, 31, 5549–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.S.; White, C.J.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Filler, S.G.; Fu, Y.; Yeaman, M.R.; Edwards, J.E., Jr.; Hennessey, J.P., Jr. NDV-3, a recombinant alum-adjuvanted vaccine for Candida and Staphylococcus aureus, is safe and immunogenic in healthy adults. Vaccine 2012, 30, 7594–7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel, M.G.; Peters, C.; Wacker, A.; Northoff, H.; Moog, R.; Boehme, A.; Silling, G.; Grimminger, W.; Einsele, H. Randomized phase III study of granulocyte transfusions in neutropenic patients. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2008, 42, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.H.; Boeckh, M.; Harrison, R.W.; McCullough, J.; Ness, P.M.; Strauss, R.G.; Nichols, W.G.; Hamza, T.H.; Cushing, M.M.; King, K.E.; et al. Efficacy of transfusion with granulocytes from G-CSF/dexamethasone-treated donors in neutropenic patients with infection. Blood 2015, 126, 2153–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, F.; Lecuit, M.; Dupont, B.; Bellaton, E.; Huerre, M.; Rohrlich, P.S.; Lortholary, O. Adjuvant corticosteroid therapy for chronic disseminated candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghi, M.; de Luca, A.; Puccetti, M.; Jaeger, M.; Mencacci, A.; Oikonomou, V.; Pariano, M.; Garlanda, C.; Moretti, S.; Bartoli, A.; et al. Pathogenic NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity during Candida Infection Is Negatively Regulated by IL-22 via Activation of NLRC4 and IL-1Ra. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease | Gene | Immune Modification | Infectious Phenotype | Non-Infectious Phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC | AIRE | Autoantibodies against at least one out of three IL-17 cytokines; IL-17A (41%), IL-17F (75%) and/or IL-22 (91%) | CMC | Autoimmune manifestations: hypoparathyroidism and adrenal insufficiency | [89,90,91,92,93] |

| STAT1 (gain-of-function) | Disruption of the IL-12 and IL-23 pathways resulting in defective Th1 and Th17 cell responses and their consecutive production of IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-22 | CMC, cutaneous and respiratory bacterial infections (mainly Staphylococcus aureus), viral skin infections (mainly Herpesviridae), invasive fungal infections | Autoimmune manifestations (hypothyroidism, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, etc), esophageal carcinoma, cerebral aneurysms | [2,94,95,96] | |

| IL-17RA, IL-17F, IL-17RC, TRAF3IP2 (encodes ACT1) | Deficiency of IL-17RA, IL-17F , IL-17RC, ACT1 causing disruption of the downstream signaling response to IL-17A and IL-17F | CMC and S. aureus skin infections | - | [72,74,97] | |

| RORC | RORγT deficiency affecting Th17 cell development | Mild CMC and severe mycobacterial infections | - | [74] | |

| IL-12B or IL-12Rβ1 | IL-12Rβ1 or IL-12p40 deficiency, affecting both IL-12 and IL-23 signaling pathways | CMC, mycobacterial infections, and Salmonella infections | - | [74] | |

| HIES | STAT3 | Defective downstream signaling of the IL-23 receptor resulting in absent IL-17 production | Mucocutaneous candidiasis, recurrent staphylococcal skin abscesses and pulmonary aspergillosis | Skeletal and dental abnormalities, pneumatoceles, eczema, eosinophilia, and elevated serum immunoglobulin E concentrations | [74] |

| DOCK8 | Disruption in Th17 differentiation | Mucocutaneous candidiasis, recurrent staphylococcal skin abscesses and pulmonary aspergillosis | Eczema, eosinophilia and, elevated serum immunoglobulin E concentrations | [1,74] | |

| RVVC | TLR2 | Reduced production of IL-17 and IFN-γ | RVVC | - | [99] |

| IL-4 | Elevated concentration of IL-4 and decreases concentration of MBL and nitric oxide (NO) in vaginal fluid | RVVC | - | [102] | |

| MBL2 | Reduced complement activation and Candida killing | RVVC | - | [100] | |

| NLPR3 | Hyper-inflammation by overproduction of IL-1β, high levels of IL-1β and low levels of IL-1Ra at the vaginal surface | RVVC | - | [30] | |

| Onychomycosis | Dectin-1 | Defective β-glucan recognition and consecutive Th17 cell responses | Onychomycosis and Candida colonization oral and gastrointestinal | - | [103,104] |

| Cutaneous candidiasis | TLR3 | Reduced CMV and Candida-induced IFN-γ and TNF-α production | Cutaneous candidiasis and CMV infection | Autoimmune manifestations: hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, pancytopenia, alopecia, enteritis | [105] |

| Candidemia | IL-10 | Increased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 | Increased susceptibility to persistent candidemia | - | [116] |

| IL-12B | Decreased production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12b, resulting in downregulation of IFN-γ production. | Increased susceptibility to persistent candidemia | - | [116] | |

| TLR1 | Decreased Candida-induced cytokine production | Increased susceptibility to acquire candidemia | - | [113] | |

| CD58 | Disruption of Candida phagocytosis and loss of inhibition of germination | Increased susceptibility to acquire candidemia | - | [114] | |

| LCE4A-C1orf68 | Disruption of mucosal integrity | Increased susceptibility to acquire candidemia | - | [114] | |

| TAGAP | Decreased Candida-induced cytokine production | Increased susceptibility to acquire candidemia | - | [114] | |

| CDC | CARD9 | Low numbers of ciruculating Th17 cells and ROS-independent selective Candida killing effect neutrophils | Recurrent mucocutaneous and invasive Candida infections (meningoencephalitis, colitis) | - | [118,119,120] |

| IL-4 | Decreased IL-4 transcriptional activity | Increased susceptibility to CDC in acute leukemia patients | - | [117] | |

| TAGAP | Decreased Candida-induced cytokine production | Increased susceptibility to Candida dissemination into organs | - | [114] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davidson, L.; Netea, M.G.; Kullberg, B.J. Patient Susceptibility to Candidiasis—A Potential for Adjunctive Immunotherapy. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010009

Davidson L, Netea MG, Kullberg BJ. Patient Susceptibility to Candidiasis—A Potential for Adjunctive Immunotherapy. Journal of Fungi. 2018; 4(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavidson, Linda, Mihai G. Netea, and Bart Jan Kullberg. 2018. "Patient Susceptibility to Candidiasis—A Potential for Adjunctive Immunotherapy" Journal of Fungi 4, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010009

APA StyleDavidson, L., Netea, M. G., & Kullberg, B. J. (2018). Patient Susceptibility to Candidiasis—A Potential for Adjunctive Immunotherapy. Journal of Fungi, 4(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010009