Characterization of Antimicrobial Compounds from Trichoderma flavipes Isolated from Freshwater Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of FBCC-F1632

2.2. DNA Extraction and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

2.4. Material Separation and Purification

2.5. Structure Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Identification of FBCC-F1632

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity of FBCC-F1632

3.3. Compound Extraction from FBCC-F1632

3.4. Structure Analysis

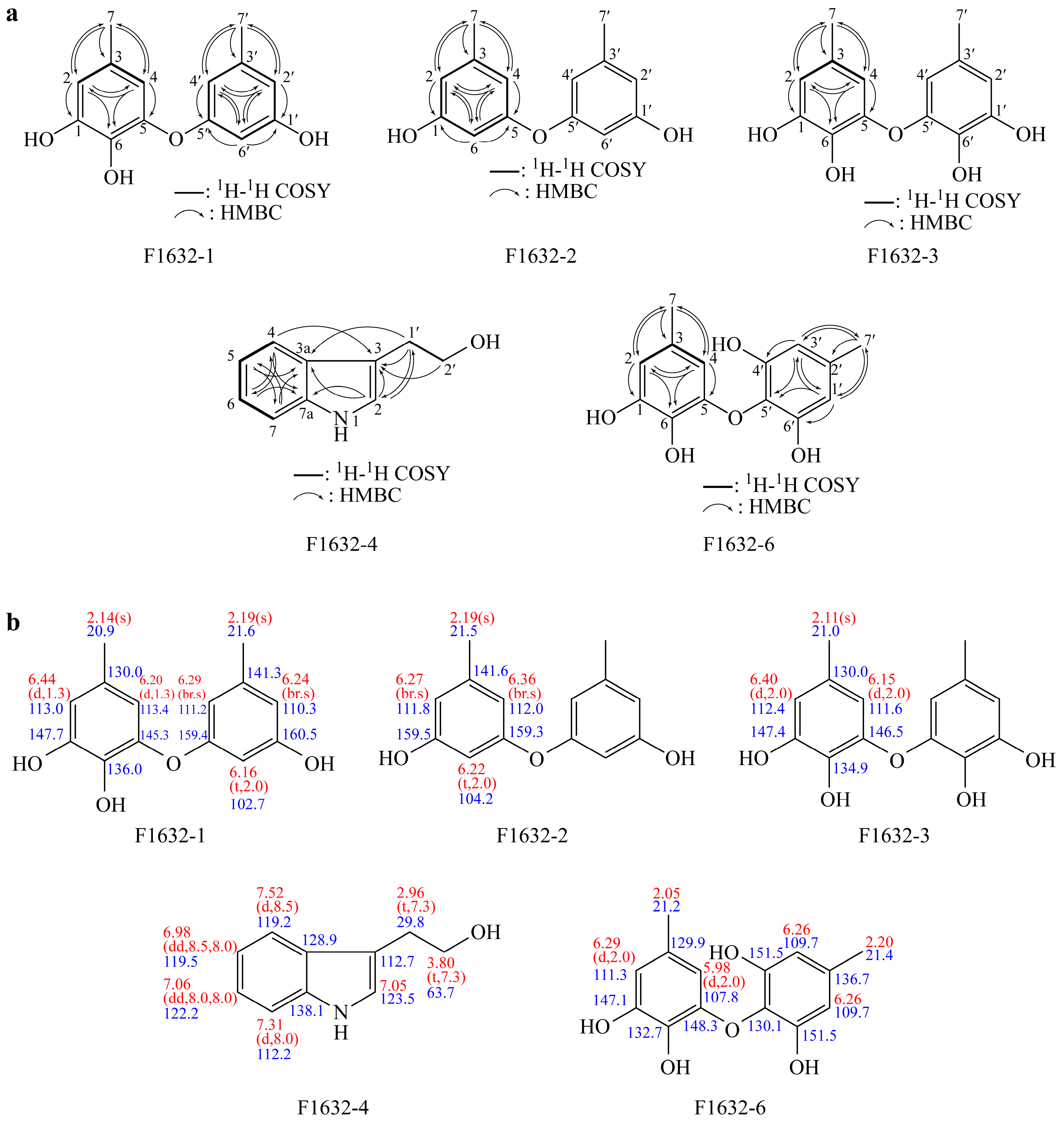

3.4.1. Structure of F1632-1

3.4.2. Structure of F1632-2

3.4.3. Structure of F1632-3

3.4.4. Structure of F1632-4

3.4.5. Structure of F1632-6

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity of Compounds Isolated from FBCC-F1632

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calabon, M.S.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; Luo, Z.-L.; Dong, W.; Hurdeal, V.G.; Gentekaki, E.; Rossi, W.; Leonardi, M.; Thiyagaraja, V.; et al. Freshwater fungal numbers. Fungal Divers. 2022, 114, 3–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Elimat, T.; Raja, H.A.; Figueroa, M.; Al Sharie, A.H.; Bunch, R.L.; Oberlies, N.H. Freshwater fungi as a source of chemical diversity: A review. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabon, M.S.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; Bao, D.; Bhunjun, C.; Phukhamsakda, C.; Shen, H.; Gentekaki, E.; Al Sharie, A.; Barros, J.; et al. Freshwater fungal biology. Mycosphere 2023, 14, 195–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarczyk, J.; Adamska, E.; Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J. Fungi and algae as sources of medicinal and other biologically active compounds: A review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerschmidt, S.; Hacker, J.; Klenk, H.-D. Threat of infection: Microbes of high pathogenic potential—Strategies for detection, control and eradication. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 295, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huemer, M.; Mairpady Shambat, S.; Brugger, S.D.; Zinkernagel, A.S. Antibiotic resistance and persistence-Implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e51034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaklitsch, W.M.; Voglmayr, H. New combinations in Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae, Hypocreales). Mycotaxon 2013, 126, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zin, N.A.; Badaluddin, N.A. Biological functions of Trichoderma spp. for agriculture applications. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020, 65, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, X. Structures and biological activities of secondary metabolites from Trichoderma harzianum. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siscar-Lewin, S.; Hube, B.; Brunke, S. Emergence and evolution of virulence in human pathogenic fungi. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 30, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Schmoll, M.; Esquivel-Ayala, B.A.; González-Esquivel, C.E.; Rocha-Ramírez, V.; Larsen, J. Mechanisms for plant growth promotion activated by Trichoderma in natural and managed terrestrial ecosystems. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 281, 127621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M.; Maebayashi, Y. Structure determination of violaceol-I and -II, new fungal metabolites from a strain of Emericella violacea. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982, 30, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuankeaw, K.; Chaiyosang, B.; Suebrasri, T.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Lumyong, S.; Boonlue, S. First report of secondary metabolites, Violaceol I and Violaceol II produced by endophytic fungus, Trichoderma polyalthiae and their antimicrobial activity. Mycoscience 2020, 61, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-F.; Lin, X.-P.; Qin, C.; Liao, S.-R.; Wan, J.-T.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Liu, J.; Fredimoses, M.; Chen, H.; Yang, B.; et al. Antimicrobial and antiviral sesquiterpenoids from sponge-associated fungus, Aspergillus sydowii ZSDS1-F6. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, G.J. Trichoderma: Systematics, the sexual state, and ecology. Phytopathology 2006, 96, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, A.; Wolna-Maruwka, A.; Pilarska, A.A.; Niewiadomska, A.; Piotrowska-Cyplik, A. Fungi of the Trichoderma genus: Future perspectives of benefits in sustainable agriculture. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bottone, E.J. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C.-N.; Tang, G.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of spices. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunyapaiboonsri, T.; Yoiprommarat, S.; Intereya, K.; Kocharin, K. New diphenyl ethers from the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps sp. BCC 1861. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Meng, W.; Cao, C.; Wang, J.; Shan, W.; Wang, Q. Antibacterial and antifungal compounds from marine fungi. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3479–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itabashi, T.; Nozawa, K.; Nakajima, S.; Kawai, K. A new azaphilone, falconensin H, from Emericella falconensis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993, 41, 2040–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, M.V.; Han, J.W.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.J. Phenyl ethers from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus tabacinus and their antimicrobial activity against plant pathogenic fungi and bacteria. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 33273–33279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position | F1632-1 | F1632-2 | F1632-3 | F1632-4 | F1632-6 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ13C (mult.) | δ1H (mult.) | δ13C (mult.) | δ1H (mult.) | δ13C (mult.) | δ1H (mult.) | δ13C (mult.) | δ1H (mult.) | δ13C (mult.) | δ1H (mult.) | |

| 1 | 147.7 | 159.5 | 147.4 | 147.1 | ||||||

| 2 | 113.0 | 6.44 (1H, d, J = 1.3 Hz) | 111.8 | 6.27 (2H, br. s) | 112.4 | 6.40 (2H, d, J = 2.0 Hz) | 123.5 | 7.05 (1H, s) | 111.3 | 6.29 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz) |

| 3 | 130.0 | 141.6 | 130.0 | 112.7 | 129.9 | |||||

| 3a | 128.9 | |||||||||

| 4 | 113.4 | 6.20 (1H, d, J = 1.3 Hz) | 112 | 6.36 (2H, br. s) | 111.6 | 6.15 (2H, d, J = 2.0 Hz) | 119.2 | 7.52 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz) | 107.8 | 5.98 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz) |

| 5 | 145.3 | 159.3 | 146.5 | 119.5 | 6.98 (1H, dd, J = 8.5, 8.0 Hz) | 148.3 | ||||

| 6 | 136.0 | 104.2 | 6.22 (2H, t, J = 2.0 Hz) | 134.9 | 122.2 | 7.06 (1H, dd, J = 8.0, 8.0 Hz) | 132.7 | |||

| 7 | 20.9 | 2.14 (3H, s) | 21.5 | 2.19 (6H, s) | 21.0 | 2.11 (6H, s) | 112.2 | 7.31 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz) | 21.2 | 2.05 (3H, s) |

| 7a | 138.1 | |||||||||

| 1′ | 160.5 | 29.8 | 2.96 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz) | 109.7 | ||||||

| 2′ | 110.3 | 6.24 (1H, br. s) | 63.7 | 3.80 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz) | 136.7 | |||||

| 3′ | 141.3 | 109.7 | 6.26 (2H, s) | |||||||

| 4′ | 111.2 | 6.29 (1H, br. s) | 151.5 | |||||||

| 5′ | 159.4 | 130.1 | ||||||||

| 6′ | 102.7 | 6.16 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz) | 151.5 | |||||||

| 7′ | 21.6 | 2.19 (3H, s) | 21.4 | 2.20 (3H, s) | ||||||

| No. | Compound | Name | MIC | MBC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | B. cereus | S. aureus | B. cereus | |||

| 1 | F1632-1 | Cordyol C | 50 | 12.5 | 50 | 25 |

| 2 | F1632-2 | Diorcinol | 50 | 25 | - | 50 |

| 3 | F1632-3 | Violaceol I | 12.5 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| 4 | F1632-4 | Tryptophol | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | F1632-6 | Violaceol II | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.T.; Cheon, W.S.; Lee, S.; Goh, J.; Lee, C.S.; Mun, H.Y. Characterization of Antimicrobial Compounds from Trichoderma flavipes Isolated from Freshwater Environments. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120857

Kim JT, Cheon WS, Lee S, Goh J, Lee CS, Mun HY. Characterization of Antimicrobial Compounds from Trichoderma flavipes Isolated from Freshwater Environments. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120857

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jeong Tae, Won Su Cheon, Sanghee Lee, Jaeduk Goh, Chang Soo Lee, and Hye Yeon Mun. 2025. "Characterization of Antimicrobial Compounds from Trichoderma flavipes Isolated from Freshwater Environments" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120857

APA StyleKim, J. T., Cheon, W. S., Lee, S., Goh, J., Lee, C. S., & Mun, H. Y. (2025). Characterization of Antimicrobial Compounds from Trichoderma flavipes Isolated from Freshwater Environments. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120857