Integrative Taxonomy Reveals Two New Trichoderma Species and a First Mexican Record from Coffee Soils in Veracruz

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Fungi

2.2. Growth Rate Determination and Morphology

2.3. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

3.2. Taxonomy

3.2.1. Trichoderma endophyticum F.B. Rocha, Samuels & P. Chaverri (Figure 4)

Description

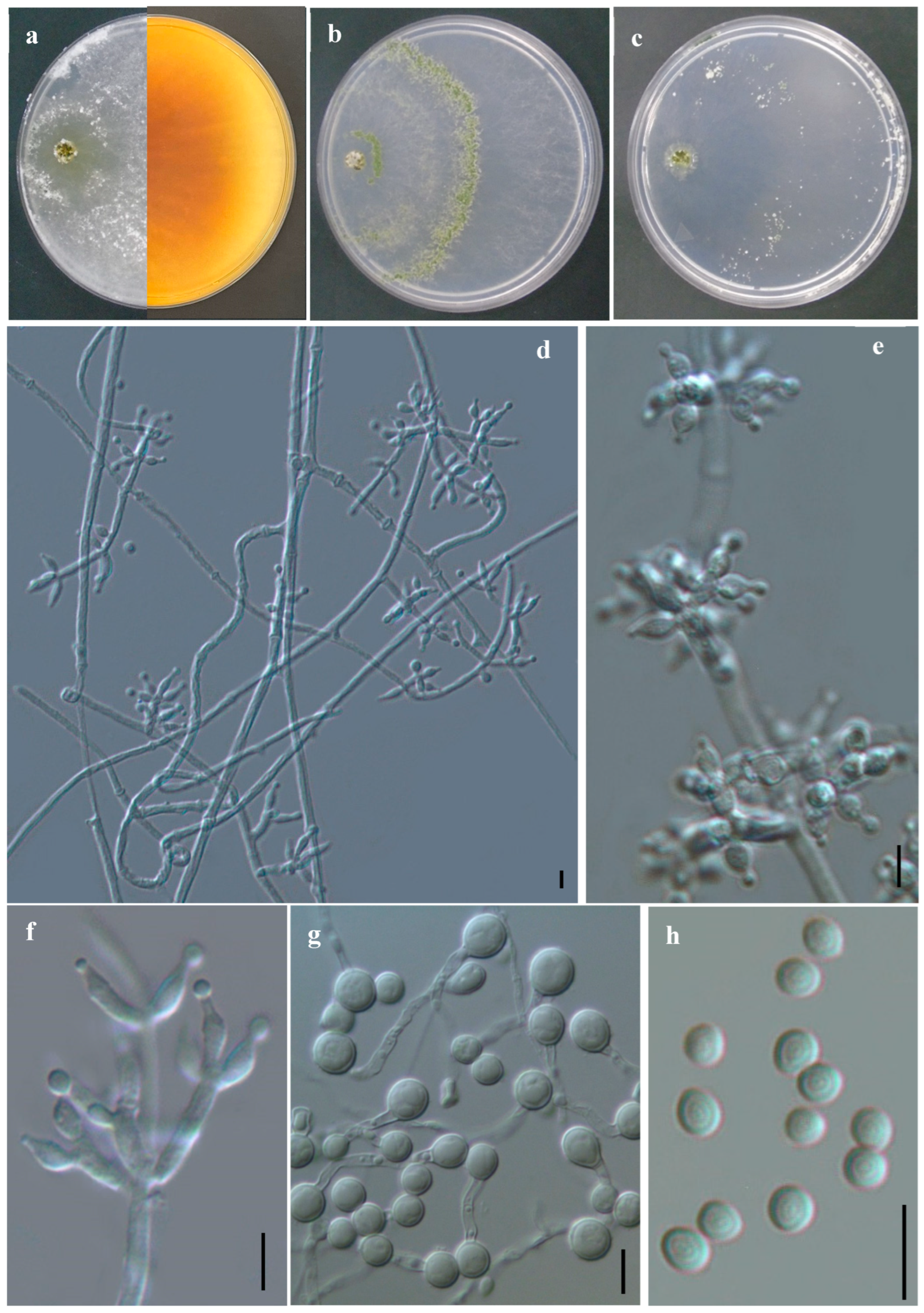

3.2.2. Trichoderma jilotepecense R. M. Arias & Gregorio-Cipriano, sp. nov. (Figure 5)

Description

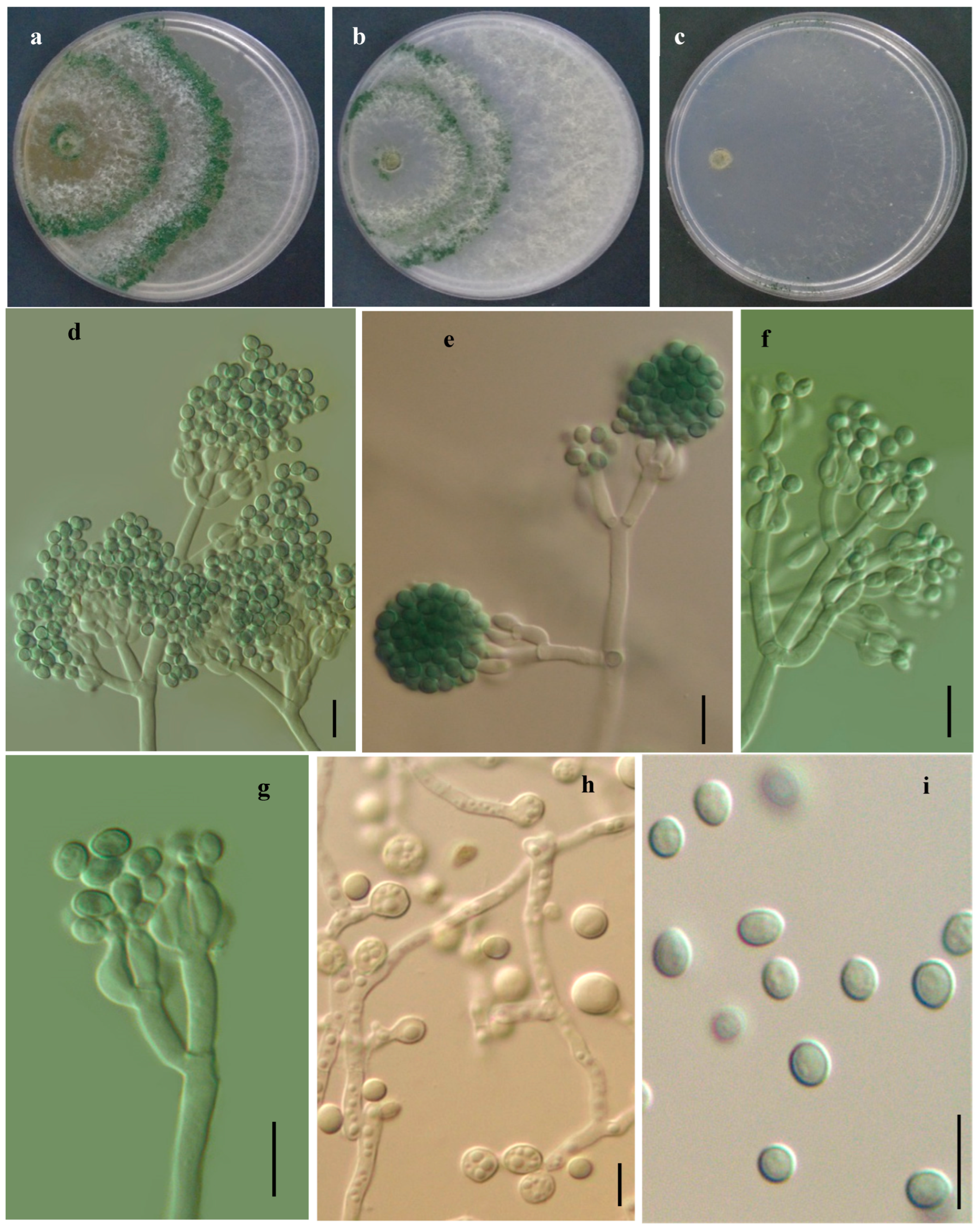

3.2.3. Trichoderma sanisidroense R. M. Arias & Heredia, sp. nov. (Figure 6)

Description

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, F.; Druzhinina, I.S. In honor of John Bissett: Authoritative guidelines on molecular identification of Trichoderma. Fungal Divers. 2021, 107, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.R.; Senanayake, I.C.; Liu, J.W.; Chen, W.J.; Dong, Z.Y.; Luos, M. Trichoderma azadirachtae sp. nov. from rhizosphere soil of Azadirachta indica from Guangdong Province, China. Phytotaxa 2024, 670, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gateta, T.; Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; Nuangmek, W.; Seemakram, W.; Srisapoomi, T.; Boonlue, S. Trichoderma thailandense sp. nov. (Hypocreales, Hypocreaceae), a new species from Thailand. Phytotaxa 2024, 669, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, G.H.S.; da Silva, R.A.F.; Zacaroni, A.B.; Silva, T.F.; Chaverri, P.; Pinho, D.B.; de Mello, S.C.M. Trichoderma collection from Brazilian soil reveals a new species: T. cerradensis sp. nov. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1279142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Chen, K.Y.; Mao, L.J.; Zhang, C.L. Eleven new species of Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae, Hypocreales) from China. Mycology 2025, 16, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, L.S.; Andrade, J.P.; Santana, L.L.; Conceição, T.D.S.; Neto, D.S.; De Souza, J.T.; Marbach, P.A.S. Redefining the clade Spirale of the genus Trichoderma by re-analyses of marker sequences and the description of new species. Fungal Biol. 2025, 129, 101529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kour, D.; Rana, K.L.; Dhiman, A.; Thakur, S.; Thakur, P.; Thakus, S.; Thakur, N.; Sudheer, S.; Yadav, N.; et al. Trichoderma: Biodiversity, ecological significances, and industrial applications. In Recent Advancement in White Biotechnology Through Fungi; Yadav, A., Mishra, S., Singh, S., Gupta, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Kumar, A.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Sajjad, H.; Olubukola, O.B.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma species: Our best fungal allies in the biocontrol of plant diseases—A review. Plants 2023, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J. Trichoderma: The current status of its application in agriculture for the biocontrol of fungal phytopathogens and stimulation of plant growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.O.; May De Mio, L.L.; Soccol, C.R. Trichoderma as a powerful fungal disease control agent for a more sustainable and healthy agriculture: Recent studies and molecular insights. Planta 2023, 257, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.S.; Doni, F.; Mispan, M.S.; Saiman, M.Z.; Yusuf, Y.M.; Oke, M.A.; Suhaimi, N.S.M. Harnessing Trichoderma in agriculture for productivity and sustainability. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedine, M.A.B.; Iacomi, B.; Tchameni, S.N.; Sameza, M.L.; Fekam, F.B. Harnessing the phosphate-solubilizing ability of Trichoderma strains to improve plant growth, phosphorus uptake and photosynthetic pigment contents in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 45, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, R.M.; Torres-Salas, A.D.; Perea-Rojas, Y.; de la Cruz Elizondo, Y. Biosolubilización de fosfato por cepas de Trichoderma in vitro y en invernadero en tres variedades de Coffea arabica. Rev. Fac. Agron. Univ. Zulia 2024, 41, e244241. [Google Scholar]

- Druzhinina, I.S.; Kopchinskiy, A.G.; Komoń, M.; Bissett, J.; Szakacs, G.; Kubicek, C.P. An oligonucleotide barcode for species identification in Trichoderma and Hypocrea. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, L.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Jaklitsch, W.M. Two hundred Trichoderma species recognized on the basis of molecular phylogeny. In Trichoderma: Biology and Applications; Mukherjee, P.K., Horwitz, B.A., Singh, U.S., Mukherjee, M., Schmoll, M., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 10–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissett, J.; Gams, W.; Jaklitsch, W.; Samuels, G.J. Accepted Trichoderma names in the year 2015. IMA Fungus 2015, 6, 263–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverri, P.; Branco-Rocha, F.; Jaklitsch, W.; Gazis, R.; Degenkolb, T.; Samuels, G.J. Systematics of the Trichoderma harzianum species complex and the re-identification of commercial biocontrol strains. Mycologia 2015, 107, 558–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Qiao, M.; Lv, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, K.Q.; Yu, Z. New species of Trichoderma isolated as endophytes and saprobes from Southwest China. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, F.; Wu, X.; Xie, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H. Five new species of Trichoderma from moist soils in China. MycoKeys 2022, 87, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, V.N.; Lana Alves, J.; Sírio Araújo, K.; de Souza Leite, T.; Borges de Queiroz, C.; Liparini Pereira, O.; de Queiroz, M.V. Endophytic Trichoderma species from rubber trees native to the Brazilian Amazon, including four new species. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1095199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Jing, T.; Sha, Y.; Mo, M.; Yu, Z. Two new Trichoderma species (Hypocreales, Hypocreaceae) isolated from decaying tubers of Gastrodia elata. MycoKeys 2023, 99, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Mao, L.J.; Zhang, C.L. Three new species of Trichoderma (Hypocreales, Hypocreaceae) from soils in China. MycoKeys 2023, 97, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, R.M.; Heredia, G. El género Trichoderma en fincas de café con diferente tipo de manejo y estructura vegetal en el centro del estado de Veracruz, México. Alianzas Y Tend. BUAP 2022, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahedo-Quero, H.O.; Aquino-Bolaños, T.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; García-Sánchez, E. Trichoderma diversity in Mexico: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diversity 2024, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, R.M.; Juárez-González, A.; Heredia, G.; de la Cruz Elizondo, Y. Capacidad fosfato solubilizadora de hongos rizosféricos provenientes de cafetales de Jilotepec, Veracruz. Alianzas Y Tend. BUAP 2022, 7, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Houbraken, J.; Spierenburg, H.; Frisvad, J.C. Rasamsonia, a new genus comprising thermotolerant and thermophilic Talaromyces and Geosmithia species. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2012, 101, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Buckley, E. A Beauveria phylogeny inferred from nuclear ITS and EF1-α sequences: Evidence for cryptic diversification and links to Cordyceps teleomorphs. Mycologia 2005, 97, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, P.W.; Mello, S.C.; Martins, I.; Silva, J.B.; Macêdo, K.; Sifuentes, D.N.; Valadares-Inglis, M.C. Trichoderma from Brazilian garlic and onion crop soils and description of two new species: T. azevedoi and T. peberdyi. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhuang, W.Y. Discovery from a large-scaled survey of Trichoderma in soil of China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverri, P.; Castlebury, L.A.; Overton, B.E.; Samuels, G.J. Hypocrea/Trichoderma: Species with conidiophore elongations and green conidia. Mycologia 2003, 95, 1100–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaklitsch, W.M.; Voglmayr, H. New combinations in Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae, Hypocreales). Mycotaxon 2013, 126, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.R.; Tan, P.; Jiang, Y.L.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Bahkali, A.H.; Kang, J.C.; Wang, Y. A novel Trichoderma species isolated from soil in Guizhou: T. guizhouense. Mycol. Prog. 2013, 12, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wang, R.; Sun, Q.; Wu, B.; Sun, J.Z. Four new species of Trichoderma in the Harzianum clade from northern China. MycoKeys 2020, 73, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaverri, P.; Samuels, G.J. Hypocrea/Trichoderma (Ascomycota, Hypocreales, Hypocreaceae): Species with green ascospores. Stud. Mycol. 2003, 48, 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, D.E.; Calderon, M.S.; Leiva, S.; Mendoza, J.E.; Arce, M.; Oliva, M. Three new species of Trichoderma in the Harzianum and Longibrachiatum lineages from Peruvian cacao crop soils based on an integrative approach. Mycologia 2021, 113, 1056–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.F.; Cai, L.; Peng, W.J.; Liu, F. Four new filamentous fungal species from newly-collected and hive-stored bee pollen. Mycosphere 2018, 9, 1089–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.D.C.; Evans, H.C.; de Abreu, L.M.; de Macedo, D.M.; Ndacnou, M.K.; Bekele, K.B.; Barreto, R.W. New species and records of Trichoderma isolated as mycoparasites and endophytes from cultivated and wild coffee in Africa. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverri, P.; Samuels, G.J.; Stewart, E.L. Hypocrea virens sp. nov., the teleomorph of Trichoderma virens. Mycologia 2001, 93, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenkolb, T.; Dieckmann, R.; Nielsen, K.F.; Gräfenhan, T.; Theis, C.; Zafari, D.; Chaverri, P.; Ismaiel, A.; Brückner, H.; Von Döhren, H.; et al. The Trichoderma brevicompactum clade: A separate lineage with new species, new peptaibiotics, and mycotoxins. Mycol. Prog. 2008, 7, 177–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.W.; Jacobson, D.J.; Kroken, S.; Kasuga, T.; Geiser, D.M.; Hibbett, D.S.; Fisher, M.C. Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000, 31, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.K.; Ly-Trong, N.; Ren, H.; Baños, H.; Roger, A.J.; Susko, E.; Bielow, C.; De Maio, N.; Goldman, N.; Hahn, M.W.; et al. IQ-TREE 3: Phylogenomic inference software using complex evolutionary models. bioRxiv 2025. submitted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree v1.4.4 Software. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, UK. 2018. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Barrera, V.A.; Iannone, L.; Romero, A.I.; Chaverri, P. Expanding the Trichoderma harzianum species complex: Three new species from Argentine natural and cultivated ecosystems. Mycologia 2021, 113, 1136–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.S.; Sousa, T.F.; da Silva, G.F.; Pedroso, R.C.; Menezes, K.S.; Soares, M.A.; Dias, G.M.; Santos, A.O.; Yamagishi, M.E.; Faria, J.V.; et al. Characterization of peptaibols produced by a marine strain of the fungus Trichoderma endophyticum via mass spectrometry, genome mining and phylogeny-based prediction. Metabolites 2023, 13, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissett, J. A revision of the genus Trichoderma. III. Section Pachybasium. Can. J. Bot. 1991, 69, 2373–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Carvajal, L.; Orduz, S.; Bissett, J. Genetic and metabolic biodiversity of Trichoderma from Colombia and adjacent neotropic regions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2009, 46, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mendoza, J.L.; Sánchez Pérez, I.M.; García Olivares, J.G.; Mayek Pérez, N.; González Prieto, J.M.; Quiroz Velásquez, J.D.C. Caracterización molecular y agronómica de aislados de Trichoderma spp. nativos del noreste de México. Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol. 2011, 13, 176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-López, V.; Martínez-Bolaños, L.; Zavala-González, E.; Ramírez-Lepe, M. Nuevos registros de Trichoderma crassum para México y su variación morfológica en diferentes ecosistemas. Rev. Mex. Micol. 2012, 36, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-De la Cruz, M.; Ortiz-García, C.F.; Bautista-Muñoz, C.; Ramírez-Pool, J.A.; Ávalos-Contreras, N.; Cappello-García, S.; De la Cruz-Pérez, A. Diversidad de Trichoderma en el agroecosistema cacao del estado de Tabasco, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2015, 86, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moo-Koh, F.A.; Cristóbal-Alejo, J.; Reyes-Ramírez, A.; Tun-Suárez, J.M.; Gamboa-Angulo, M. Identificación molecular de aislados de Trichoderma spp. y su actividad promotora en Solanum lycopersicum L. Investig. Cienc. Univ. Auton. Aguascalientes 2017, 71, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, B.M.; Espinosa-Huerta, E.; Villordo-Pineda, E.; Rodríguez-Guerra, R.; Mora-Avilés, M.A. Identificación molecular y evaluación antagónica in vitro de cepas nativas de Trichoderma spp. sobre hongos fitopatógenos de raíz en frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cv. Montcalm. Agrociencia 2017, 51, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Espinosa, A.C.; Villarruel-Ordaz, J.L.; Maldonado-Bonilla, L.D. Mycoparasitic antagonism of a Trichoderma harzianum strain isolated from banana plants in Oaxaca, Mexico. Biotecnia 2020, 1, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persiani, A.; Maggi, O. Fungal communities in the rhizosphere of Coffea arabica L. in Mexico. Mycol. Ital. 1988, 2, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Okoth, S.A.; Okoth, P.; Muya, E. Influence of soil chemical and physical properties on occurrence of Trichoderma spp. in Embu, Kenya. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2009, 11, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Belayneh-Mulaw, T.; Kubicek, C.P.; Druzhinina, I.S. The rhizosphere of Coffea arabica in its native highland forests of Ethiopia provides a niche for a distinguished diversity of Trichoderma. Diversity 2010, 2, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulatu, A.; Megersa, N.; Abena, T.; Kanagarajan, S.; Liu, Q.; Tenkegna, T.A.; Vetukuri, R.R. Biodiversity of the genus Trichoderma in the rhizosphere of coffee (Coffea arabica) plants in Ethiopia and their potential use in biocontrol of coffee wilt disease. Crops 2022, 2, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende-Molar, R.; Báez-Parra, K.M.; Salazar-Villa, E.; Rojo-Báez, I. Biodiversity of Trichoderma spp. in Mexico and its potential use in agriculture. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2022, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Strain/Voucher | Origin | GenBank Accession Number | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | tef1 | rpb2 | ||||

| Trichoderma afarasin | G.J.S. 06-98 = CBS 130501 | Cameroon | FJ463400 | FJ463327 | — | [17] |

| T. afarasin | G.J.S. 99-227 = CBS 130755 T | Cameroon | AY027784 | AF348093 | — | [17] |

| T. anaharzianum | YMF 1.00383 T | China | MH113931 | MH183182 | MH158995 | [18] |

| T. asiaticum | YMF 1.00352 T | China | MH113930 | MH183183 | MH158994 | [18] |

| T. azevedoi | CEN 1422 T | Brazil | MK714902 | MK696660 | MK696821 | [30] |

| T. bannaense | HMAS 248840 = CGMCC 3.18394 T | China | KY687923 | KY688037 | KY687979 | [31] |

| T. breve | HMAS 248844 = CGMCC 3.18398 T | China | KY687927 | KY688045 | KY687983 | [31] |

| T. corneum | G.J.S. 97-75 = CBS 100541 T | Thailand | — | AY937431 | KJ842183 | [32,33] |

| T. crassum | DAOM 164916 T | Canada | EU280067 | EU280048 | KJ842185 | [32] |

| T. densissimum | T32434 = CGMCC 3.24126 T | China | — | OP357971 | OP357966 | [22] |

| T. endophyticum | Dis 217h = CBS 130730 | Ecuador | FJ442242 | FJ463314 | FJ442721 | [17] |

| T. endophyticum | Dis 217a = CBS 130729 T | Ecuador | FJ442243 | FJ463319 | — | [17] |

| T. endophyticum | Dis 218f = CBS 130753 | Ecuador | FJ442246 | FJ463326 | FJ442722 | [17] |

| T. endophyticum | Dis 221d | Ecuador | FJ442248 | FJ463389 | FJ442794 | [17] |

| T. endophyticum | IE7006 | Mexico | PV687649 | PV694681 | PV694674 | This study |

| T. graminis | YNE00410 = GDMCC3.1013 T | China | — | OR779514 | OR779491 | [5] |

| T. guizhouense | HGUP0038 = CBS 131803 T | China | JN191311 | JN215484 | JQ901400 | [34] |

| T. inhamatum | CBS 273.78 T | Colombia | FJ442680 | AF348099 | FJ442725 | [16] |

| T. jilotepecense | IE7000 T | Mexico | PV687646 | PV694678 | PV694671 | This study |

| T. jilotepecense | IE7001 | Mexico | PV687647 | PV694679 | PV694672 | This study |

| T. jilotepecense | IE7002 | Mexico | PV687648 | PV694680 | PV694673 | This study |

| T. lentinulae | HMAS 248256 = CGMCC 3.19847 T | China | MN594469 | MN605878 | MN605867 | [35] |

| T. neocrassum | G.J.S. 01-227 = CBS 114230 T | Thailand | — | JN133572 | AY481587 | [16,36] |

| T. neoguizhouense | T33324 = GDMCC3.1012 T | China | — | OR779516 | OR779487 | [5] |

| T. peruvianum | CHAX CP15-2 T | Peru | — | MW480145 | MW480153 | [37] |

| T. pollinicola | LC11682 = LF1542 = CGMCC 3.18781 T | China | MF939592 | MF939619 | MF939604 | [38] |

| T. pseudopyramidale | COAD 2426 T | Ethiopia | — | MK044131 | MK044224 | [39] |

| T. sanisidroense | IE7003 | Mexico | PV687650 | PV694682 | PV694675 | This study |

| T. sanisidroense | IE7004 T | Mexico | PV687651 | PV694683 | PV694676 | This study |

| T. sanisidroense | IE7005 | Mexico | PV687652 | PV694684 | PV694677 | This study |

| T. shaanxiense | T32000 = GDMCC3.1014 T | China | — | OR779513 | OR779486 | [5] |

| T. virens | Gli 39 = ATCC 13213 = CBS 249.59 T | USA | AF099005 | AF534631 | AF545558 | [16,36,40] |

| T. virens | G.J.S. 01-287 | Cote d’Ivoire | DQ083023 | AY750894 | EU341804 | [41] |

| T. zelobreve | HMAS 248254 = CGMCC 3.19695 T | China | MN594474 | MN605883 | MN605872 | [35] |

| T. chlamydosporum OT | HMAS 248850 = CGMCC 3.18401 T | China | KY687933 | KY688052 | KY687989 | [31] |

| T. ganodermatis OT | HMAS 248856 = CGMCC 3.18405 T | China | KY687939 | KY688060 | KY687995 | [31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arias Mota, R.M.; Gregorio Cipriano, R.; Martínez Santos, A.G.; Heredia Abarca, G. Integrative Taxonomy Reveals Two New Trichoderma Species and a First Mexican Record from Coffee Soils in Veracruz. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120856

Arias Mota RM, Gregorio Cipriano R, Martínez Santos AG, Heredia Abarca G. Integrative Taxonomy Reveals Two New Trichoderma Species and a First Mexican Record from Coffee Soils in Veracruz. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120856

Chicago/Turabian StyleArias Mota, Rosa María, Rosario Gregorio Cipriano, Alondra Guadalupe Martínez Santos, and Gabriela Heredia Abarca. 2025. "Integrative Taxonomy Reveals Two New Trichoderma Species and a First Mexican Record from Coffee Soils in Veracruz" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120856

APA StyleArias Mota, R. M., Gregorio Cipriano, R., Martínez Santos, A. G., & Heredia Abarca, G. (2025). Integrative Taxonomy Reveals Two New Trichoderma Species and a First Mexican Record from Coffee Soils in Veracruz. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120856