Environmental Compatibility of Penicillium rubens Strain 212: Impact on Indigenous Soil Fungal Community Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture Conditions and Plant Material

2.2. Field Trials and Sampling

2.3. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

2.4. DGGE Profiling and Sequence Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fungal Community Profiles and Diversity

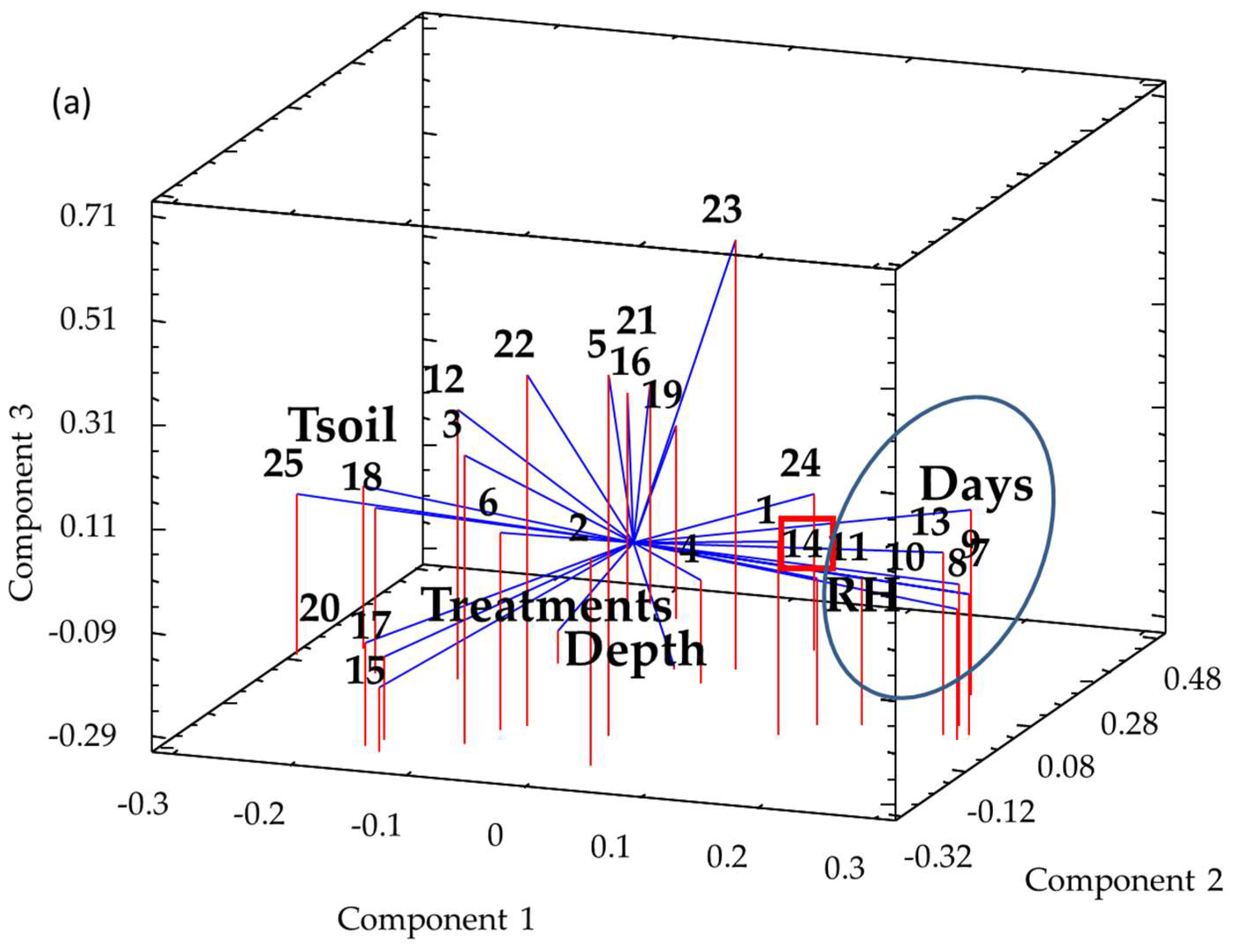

3.2. Temporal and Spatial Dynamics vs. Treatment Effects

3.3. Identification of Indigenous Fungi

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCA | Biocontrol agent |

| AMOVA | Analysis of molecular variance |

| AM | arbuscular mycorrhizal |

| C | Untreated control |

| CSPO | Dry powder inocula |

| LC | Field trial experiment-La canaleja |

| OTU | Operational taxonomic unit |

| P | 6–10 cm soil depth |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PCR-DGGE | Polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis |

| PO212 | Penicillium rubens strain PO212 |

| S | 0–5 cm soil depth |

| UPGMA | UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean |

| VO | Field trial experiment-Villaviciosa de Odón |

References

- Fierer, N. Embracing the Unknown: Disentangling the Complexities of the Soil Microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Van Der Putten, W.H. Belowground Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimner, T.A.; Boland, G.J. A Review of the Non-Target Effects of Fungi Used to Biologically Control Plant Diseases. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 100, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Hou, R.; Li, J.; Lyu, Y.; Hang, S.; Gong, H.; Ouyang, Z. Effects of Different Fertilizers on Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities of Winter Wheat in the North China Plain. Agronomy 2020, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, J.W.M.; Olsson, P.A.; Falkengren-Grerup, U. Root Colonisation by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal, Fine Endophytic and Dark Septate Fungi across a pH Gradient in Acid Beech Forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, A.; Benhamou, N.; Chet, I.; Piché, Y. Mycoparasitism of am fungi by Trichoderma harzianum: Ultrastructural and cytochemical aspects of the interaction. Phytopathology 1996, 86, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-J.; Koske, R.E. Gigaspora Gigantea: Parasitism of Spores by Fungi and Actinomycetes. Mycol. Res. 1994, 98, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fravel, D.R. Commercialization and Implementation of Biocontrol. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plazinski, J.; Rolfe, B.G. Influence of Azospirillum Strains on the Nodulation of Clovers by Rhizobium Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1985, 49, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bayona, L.; Comstock, L.E. Bacterial Antagonism in Host-Associated Microbial Communities. Science 2018, 361, eaat2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Crowley, D.E.; Borneman, J.; Keen, N.T. Microbial Phyllosphere Populations Are More Complex than Previously Realized. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3889–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savazzini, F.; Longa, C.M.O.; Pertot, I. Impact of the Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma atroviride SC1 on Soil Microbial Communities of a Vineyard in Northern Italy. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpouzas, D.G.; Karatasas, A.; Spiridaki, E.; Rousidou, C.; Bekris, F.; Omirou, M.; Ehaliotis, C.; Papadopoulou, K.K. Impact of a Beneficial and of a Pathogenic Fusarium Strain on the Fingerprinting-Based Structure of Microbial Communities in Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Milll.) Rhizosphere. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2011, 47, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windels, C.E. Factors Affecting Penicillium oxalicum as a Seed Protectant Against Seedling Blight of Pea. Phytopathology 1978, 68, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.; Melgarejo, P.; De Cal, A.; Larena, I. Persistence, Survival, Vertical Dispersion, and Horizontal Spread of the Biocontrol Agent, Penicillium oxalicum Strain 212, in Different Soil Types. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2013, 67, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, M.; Walsh, C.J.; Crispie, F.; O’Sullivan, O.; Cotter, P.D.; Van Sinderen, D.; Kenny, J.G. Evaluating the Efficiency of 16S-ITS-23S Operon Sequencing for Species Level Resolution in Microbial Communities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larena, I.; Melgarejo, P. Development of a Method for Detection of the Biocontrol Agent Penicillium oxalicum Strain 212 by Combining PCR and a Selective Medium. Plant Dis. 2009, 93, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cal, A.; Garcia-Lepe, R.; Melgarejo, P. Induced Resistance by Penicillium oxalicum Against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici: Histological Studies of Infected and Induced Tomato Stems. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larena, I.; Sabuquillo, P.; Melgarejo, P.; De Cal, A. Biocontrol of Fusarium and Verticillium Wilt of Tomato by Penicillium oxalicum under Greenhouse and Field Conditions. J. Phytopathol. 2003, 151, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larena, I.; Vázquez, G.; De Cal, A.; Melgarejo, P.; Magan, N. Ecophysiological Requirements on Growth and Survival of the Biocontrol Agent Penicillium oxalicum 212 in Different Sterile Soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 78, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, S.; Rico, J.R. Ecophysiological Factors Affecting Growth, Sporulation and Survival of the Biocontrol Agent Penicillium oxalicum. Mycopathologia 1997, 139, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Polli, F.; Schütze, T.; Viggiano, A.; Mózsik, L.; Jung, S.; De Vries, M.; Bovenberg, R.A.L.; Meyer, V.; Driessen, A.J.M. A Penicillium rubens Platform Strain for Secondary Metabolite Production. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarino, M.; De Cal, A.; Melgarejo, P.; Larena, I.; Espeso, E.A. The development of genetic and molecular markers to register and commercialize Penicillium rubens strain 212 (formerly Penicillium oxalicum strain 212) as a biocontrol agent. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1439 of 31 August 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 283/2013 as regards the information to be submitted for active substances and the specific data requirements for micro-organisms. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, L 224, 1–25. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/1439/oj (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Muyzer, G.; De Waal, E.C.; Uitterlinden, A.G. Profiling of Complex Microbial Populations by Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis Analysis of Polymerase Chain Reaction-Amplified Genes Coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, I.C.; Campbell, C.D.; Prosser, J.I. Diversity of Fungi in Organic Soils under a Moorland—Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bent, S.J.; Pierson, J.D.; Forney, L.J. Measuring Species Richness Based on Microbial Community Fingerprints: The Emperor Has No Clothes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 2399–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larena, I.; Melgarejo, P.; De Cal, A. Production, Survival, and Evaluation of Solid-Substrate Inocula of Penicillium oxalicum, a Biocontrol Agent Against Fusarium Wilt of Tomato. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larena, I.; Melgarejo, P.; De Cal, A. Drying of Conidia of Penicillium oxalicum, a Biological Control Agent against Fusarium Wilt of Tomato. J. Phytopathol. 2003, 151, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cal, A.; García-Lepe, R.; Pascual, S.; Melgarejo, P. Effects of Timing and Method of Application of Penicillium oxalicum on Efficacy and Duration of Control of Fusarium Wilt of Tomato. Plant Pathol. 1999, 48, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, E.; Leeflang, P.; Glandorf, B.; Dirk van Elsas, J.; Wernars, K. Analysis of Fungal Diversity in the Wheat Rhizosphere by Sequencing of Cloned PCR-Amplified Genes Encoding 18S rRNA and Temperature Gradient Gel Electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2614–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications 18; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS Primers with Enhanced Specificity for Basidiomycetes—Application to the Identification of Mycorrhizae and Rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, B.; Kim, S.-A.; Han, N.S. Bacterial and Fungal Diversity in Laphet, Traditional Fermented Tea Leaves in Myanmar, Analyzed by Culturing, DNA Amplicon-Based Sequencing, and PCR-DGGE Methods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 320, 108508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Excoffier, L.; Smouse, P.E.; Quattro, J.M. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: Application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirmans, P.G.; Liu, S. Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) for Autopolyploids. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Genetic Distance between Populations. Am. Nat. 1972, 106, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.L.; Ramirez, K.S.; Aanderud, Z.; Lennon, J.; Fierer, N. Temporal Variability in Soil Microbial Communities across Land-Use Types. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Ramírez, N.R.; Craven, D.; Reich, P.B.; Ewel, J.J.; Isbell, F.; Koricheva, J.; Parrotta, J.A.; Auge, H.; Erickson, H.E.; Forrester, D.I.; et al. Diversity-Dependent Temporal Divergence of Ecosystem Functioning in Experimental Ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1639–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ai, C.; Ding, W.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Hou, Y.; He, P. The Response of Soil Fungal Diversity and Community Composition to Long-Term Fertilization. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 140, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, S.; Iasur Kruh, L. Balancing Nature and Nurture: The Role of Biocontrol Agents in Shaping Plant Microbiomes for Sustainable Agriculture. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, C.; Eichmeier, A.; Štůsková, K.; Armengol, J.; Bujanda, R.; Fontaine, F.; Trotel-Aziz, P.; Gramaje, D. Establishment of Biocontrol Agents and Their Impact on Rhizosphere Microbiome and Induced Grapevine Defenses Are Highly Soil-Dependent. Phytobiomes J. 2024, 8, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, C.; Alabouvette, C. Effects of the Introduction of a Biocontrol Strain of Trichoderma Atroviride on Non Target Soil Micro-Organisms. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2009, 45, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockett, B.F.T.; Prescott, C.E.; Grayston, S.J. Soil Moisture Is the Major Factor Influencing Microbial Community Structure and Enzyme Activities across Seven Biogeoclimatic Zones in Western Canada. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 44, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, E.; Carreras, M.; Espeso, E.A.; Larena, I. A role for Penicillium rubens strain 212 xylanolytic system in biocontrol of Fusarium wilt disease in tomato plants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 167, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variation Source | d.f. | Variance Components | % Total Variation | Fst | p |

| All distances: two groups | |||||

| Between depths | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Within depths | 36 | 4.49 | 100 | −0.004 | 0.447 |

| All treatments: two groups | |||||

| Between treatments | 1 | 0.16 | 4 | ||

| Within treatments | 36 | 4.41 | 96 | 0.036 | 0.124 |

| All sampling dates: four groups | |||||

| Between sampling dates | 3 | 2.76 | 53 | ||

| Within sampling dates | 34 | 2.41 | 47 | 0.534 | 0.0001 * |

| Variation Source | d.f. | Variance Components | % Total Variation | Fst | p |

| All distances: two groups | |||||

| Between depths | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | |

| Within depths | 36 | 3.5 | 100 | 0.034 | 0.987 |

| All treatments: two groups | |||||

| Between treatments | 1 | 0.38 | 11 | ||

| Within treatments | 36 | 3.27 | 89 | 0.105 | 0.003 |

| All sampling dates: four groups | |||||

| Between sampling dates | 3 | 1.55 | 41 | ||

| Within sampling dates | 34 | 2.28 | 59 | 0.406 | 0.0001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guijarro, B.; Vázquez, G.; De Cal, A.; Melgarejo, P.; Gaju, N.; Martínez-Alonso, M.; Larena, I. Environmental Compatibility of Penicillium rubens Strain 212: Impact on Indigenous Soil Fungal Community Dynamics. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120852

Guijarro B, Vázquez G, De Cal A, Melgarejo P, Gaju N, Martínez-Alonso M, Larena I. Environmental Compatibility of Penicillium rubens Strain 212: Impact on Indigenous Soil Fungal Community Dynamics. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):852. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120852

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuijarro, Belén, Gema Vázquez, Antonieta De Cal, Paloma Melgarejo, Núria Gaju, Maira Martínez-Alonso, and Inmaculada Larena. 2025. "Environmental Compatibility of Penicillium rubens Strain 212: Impact on Indigenous Soil Fungal Community Dynamics" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120852

APA StyleGuijarro, B., Vázquez, G., De Cal, A., Melgarejo, P., Gaju, N., Martínez-Alonso, M., & Larena, I. (2025). Environmental Compatibility of Penicillium rubens Strain 212: Impact on Indigenous Soil Fungal Community Dynamics. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120852