BcHK71 and BcHK67, Two-Component Histidine Kinases, Regulate Conidial Morphogenesis, Glycerol Synthesis, and Virulence in Botrytis cinerea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strains, Culture Conditions, and Transformation

2.2. Nucleic Acid Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.4. Gene Deletion and Mutant Verification

2.5. Fungal Developmental Assays

2.6. Pathogenicity Tests

2.7. Stress Adaptation Assays

2.8. Western-Blot Analysis of Phosphorylation of Hog1

2.9. Ecto-ATPase Activity Assay

2.10. Transcriptome Analysis

2.11. RT-qPCR Analysis of the Botrydial Biosynthetic Gene Cluster and HOG-MAPK Pathway Genes

2.12. Microscopy and Image Analyses

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of BcHK71 and BcHK67 Genes in B. cinerea

3.2. Disruption of BcHK71 and BcHK67

3.3. BcHK71 and BcHK67 Are Required for Vegetative Development

3.4. BcHK71 and BcHK67 Are Involved in Asexual and IFSs Development

3.5. BcHK71 and BcHK67 Are Virulence Determinants of B. cinerea

3.6. Deletion of BcHK71 and BcHK67 Alters Stress Adaptation and Fungicide Sensitivity

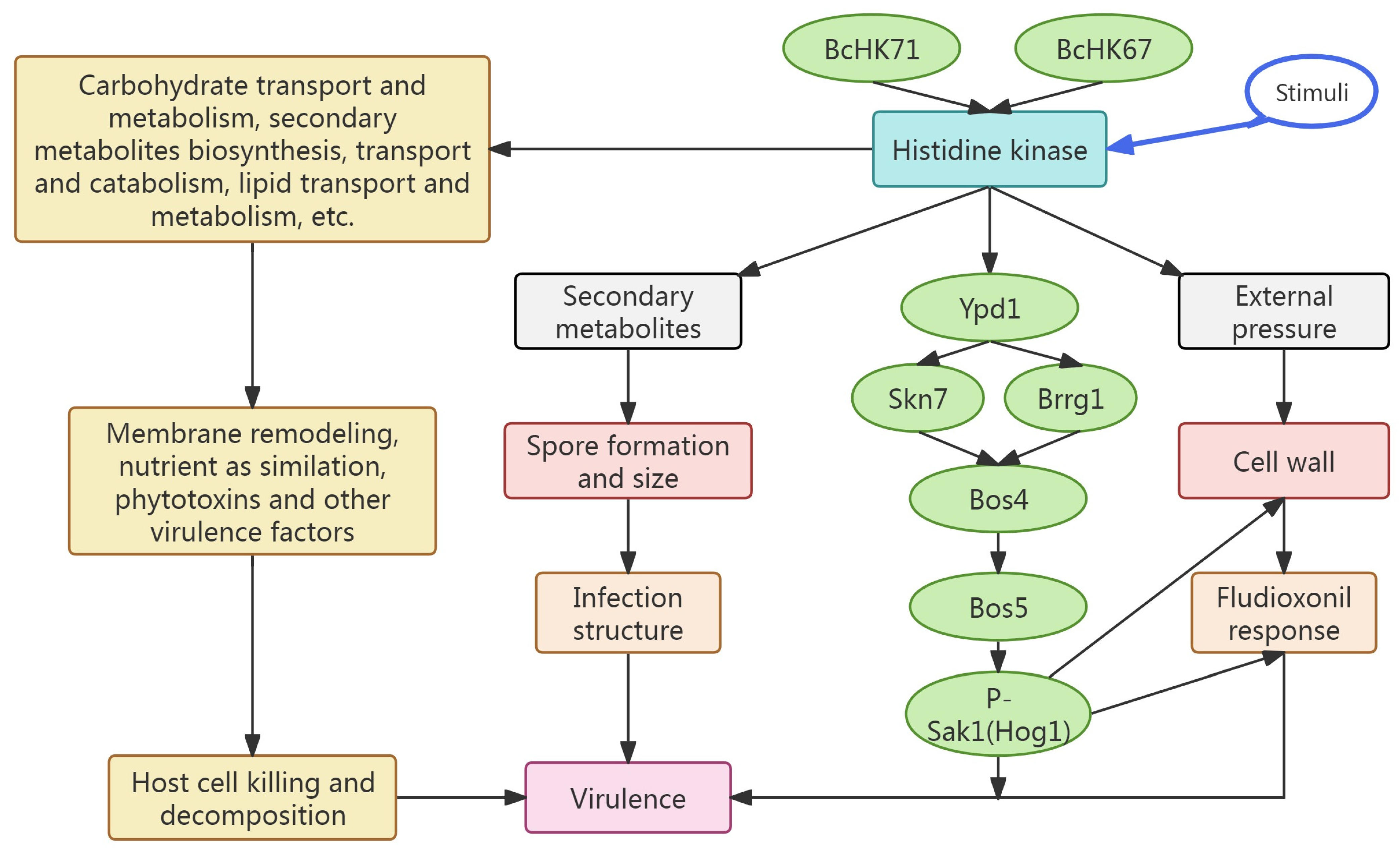

3.7. BcHK71 and BcHK67 Deletion Affects the Expression of Ypd1, Brrg1 and Skn7

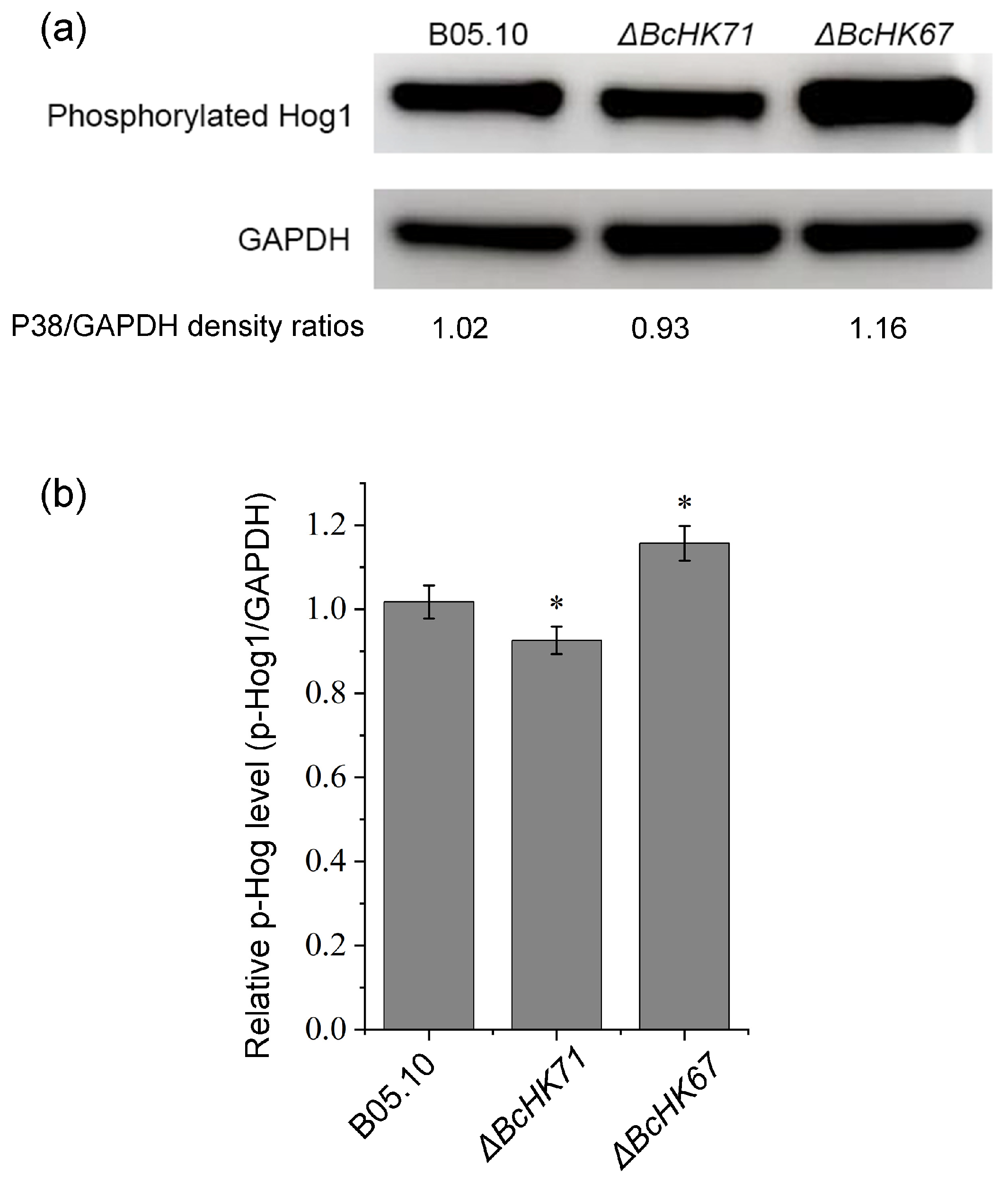

3.8. Effect on BcHog1 Phosphorylation by BcHK71 and BcHK67

3.9. Transcriptomic Alterations in ΔBcHK71 and ΔBcHK67

3.10. Transcriptional Alterations in the Botrydial Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

3.11. Expression of HOG-MAPK Pathway Genes in ΔBcHK71 and ΔBcHK67 Mutants

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Domains of BcHK71 and BcHK67

4.2. Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolutionary Implications

4.3. Roles of BcHK71 and BcHK67 in Development

4.4. BcHK71 and BcHK67 Are Required for Full Virulence

4.5. Roles of BcHK71 and BcHK67 Under Various Stresses

4.6. BcHK71 and BcHK67 Influence Fungicide Sensitivity and Glycerol Biosynthesis

4.7. BcHK71 and BcHK67 Are Required for Downstream Signaling in the Two-Component System

4.8. Distinctive Role of Group XI HKs in Virulence Regulation

4.9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fillinger, S.; Elad, Y. Botrytis-the Fungus, the Pathogen and Its Management in Agricultural Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weiberg, A.; Wang, M.; Lin, F.M.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kaloshian, I.; Huang, H.-D.; Jin, H. Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science 2013, 342, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; Foster, G.D. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Chang, H.W.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Ding, Y.H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Cao, S.-N.; Li, L.-T.; et al. The key gluconeogenic gene PCK1 is crucial for virulence of Botrytis cinerea via initiating its conidial germination and host penetration. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 1794–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choquer, M.; Rascle, C.; Gonçalves, I.R.; de Vallée, A.; Ribot, C.; Loisel, E.; Smilevski, P.; Ferria, J.; Savadogo, M.; Souibgui, E.; et al. The infection cushion of Botrytis cinerea: A fungal ‘weapon’ of plant-biomass destruction. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 2293–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kan, J.A. Infection strategies of Botrytis cinerea. In VIII International Symposium on Postharvest Physiology of Ornamental Plants 669; Marissen, N., van Doorn, W.G., van Meeteren, U., Eds.; International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS): Korbeek-Lo, Belgium, 2003; pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, E.J.; Laub, M.T. Evolution of two-component signal transduction systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 66, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Li, C.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L. Targeting new functions and applications of bacterial two-component systems. ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202400392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koretke, K.K.; Lupas, A.N.; Warren, P.V.; Rosenberg, M.; Brown, J.R. Evolution of two-component signal transduction. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 1956–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, J.L.; Parkinson, J.S.; Bourret, R.B. Signal transduction via the multi-step phosphorelay: Not necessarily a road less traveled. Cell 1996, 86, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.; Malakasi, P.; Smith, D.A.; Cheetham, J.; Buck, V.; Millar, J.B.; Morgan, B.A. Two-component mediated peroxide sensing and signal transduction in fission yeast. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimi, A.; Hagiwara, D.; Ono, M.; Fukuma, Y.; Midorikawa, Y.; Furukawa, K.; Fujioka, T.; Mizutani, O.; Sato, N.; Miyazawa, K.; et al. Downregulation of the ypdA gene encoding an intermediate of His-Asp phosphorelay signaling in Aspergillus nidulans induces the same cellular effects as the phenylpyrrole fungicide fludioxonil. Front. Fungal Biol. 2021, 2, 675459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catlett, N.L.; Yoder, O.C.; Turgeon, B.G. Whole-genome analysis of two-component signal transduction genes in fungal pathogens. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, H.R.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A. Putative osmosensor-OsHK3b-a histidine kinase protein from rice shows high structural conservation with its ortholog AtHK1 from Arabidopsis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2014, 32, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourret, R.B.; Borkovich, K.A.; Simon, M.I. Signal transduction pathways involving protein phosphorylation in prokaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biochem 1991, 60, 401–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A.F.; Georgellis, D. The role of sensory kinase proteins in two-component signal transduction. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, B.; Ye, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, X.; Ren, B. The two-component signal transduction system and its regulation in Candida albicans. Virulence 2021, 12, 1884–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, A.H.; Stock, A.M. Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001, 26, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posas, F.; Wurgler-Murphy, S.M.; Maeda, T.; Witten, E.A.; Thai, T.C.; Saito, H. Yeast HOG1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multistep phosphorelay mechanism in the SLN1–YPD1–SSK1 “two-component” osmosensor. Cell 1996, 86, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaserer, A.O.; Andi, B.; Cook, P.F.; West, A.H. Effects of osmolytes on the SLN1-YPD1-SSK1 phosphorelay system from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 8044–8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H. Histidine phosphorylation and two-component signaling in eukaryotic cells. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2497–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispail, N.; Soanes, D.M.; Ant, C.; Czajkowski, R.; Grünler, A.; Huguet, R.; Perez-Nadales, E.; Poli, A.; Sartorel, E.; Valiante, V.; et al. Comparative genomics of MAP kinase and calcium-calcineurin signalling components in plant and human pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2009, 46, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, T.; Kadokura, K.; Ohira, T.; Ichiishi, A.; Fujimura, M.; Yamaguchi, I.; Kudo, T. A two-component histidine kinase of the rice blast fungus is involved in osmotic stress response and fungicide action. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viefhues, A.; Schlathoelter, I.; Simon, A.; Viaud, M.; Tudzynski, P. Unraveling the function of the response regulator BcSkn7 in the stress signaling network of Botrytis cinerea. Eukaryot. Cell 2015, 14, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimi, A.; Kojima, K.; Takano, Y.; Tanaka, C. Group III histidine kinase is a positive regulator of Hog1-type mitogen-activated protein kinase in filamentous fungi. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 1820–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, J.P.; Xu, P.; Gunawardena, J.; McClean, M.N. Robust network structure of the Sln1-Ypd1-Ssk1 three-component phospho-relay prevents unintended activation of the HOG MAPK pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Syst. Biol. 2015, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Z. The transmembrane protein FgSho1 regulates fungal development and pathogenicity via the MAPK module Ste50-Ste11-Ste7 in Fusarium graminearum. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Jiang, C. Combatting Fusarium head blight: Advances in molecular interactions between Fusarium graminearum and wheat. Phytopathol. Res. 2022, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, P.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, R.; Jiang, C.; Wang, G. Insights into intracellular signaling network in Fusarium species. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaud, M.; Fillinger, S.; Liu, W.; Polepalli, J.S.; Le Pêcheur, P.; Kunduru, A.R.; Leroux, P.; Legendre, L. A class III histidine kinase acts as a novel virulence factor in Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liu, N.; Sang, C.; Shi, D.; Zhou, M.; Chen, C.; Qin, Q.; Chen, W. The autophagy gene BcATG8 regulates the vegetative differentiation and pathogenicity of Botrytis cinerea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02455-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, H.S.; Kang, S.; Lee, Y.H. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of the plant pathogenic fungus, Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Cells 2001, 12, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichloas, N.B. GeneDoc: Analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBnet News 1997, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gebali, S.; Mistry, J.; Bateman, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Luciani, A.; Potter, S.C.; Qureshi, M.; Richardson, L.J.; Salazar, G.A.; Smart, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D427–D432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Copley, R.R.; Doerks, T.; Ponting, C.P.; Bork, P. SMART: A web-based tool for the study of genetically mobile domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Wen, L.; Gao, X.; Jin, C.; Xue, Y.; Yao, X. DOG 1.0: Illustrator of protein domain structures. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Jiang, H.; Chai, R.; Mao, X.; Qiu, H.; Liu, F.; et al. MoPex19, which is essential for maintenance of peroxisomal structure and woronin bodies, is required for metabolism and development in the rice blast fungus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, M.X.; Guo, J.; Hao, Z.N.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.Q.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhu, X.M.; Wang, Y.L.; Chen, J.; et al. The peroxins BcPex8, BcPex10, and BcPex12 are required for the development and pathogenicity of Botrytis cinerea. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 962500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, J.B.; Dhingra, O.D. Basic Plant Pathology Methods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, T.J. ImageJ for microscopy. Biotechniques 2007, 43 (Suppl. S1), S25–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002, 350, 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology Consortium. The gene ontology resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D330–D338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolde, R.; Kolde, M.R. Package ‘pheatmap’. R Package 2015, 1, 790. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Wickham, M.H. Package ‘ggplot2’. Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics. Version 2016, 2, 1–189. [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, S.; Skaletsky, H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols; Krawetz, S., Misener, S., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 365–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron, B.P.; Rouse, R.G. Imageview: A High-Level Authoring Tool for Repurposing Multimedia Content. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 1994, 11, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnett, C.W. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1955, 50, 1096–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.Y.; Zhang, C.X. Data Processing System (DPS) software with experimental design, statistical analysis and data mining developed for use in entomological research. Insect Sci. 2013, 20, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papon, N.; Stock, A.M. Two-component systems. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R724–R725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassler, J.S.; West, A.H. Histidine phosphotransfer proteins in fungal two-component signal transduction pathways. Eukaryot. Cell 2013, 12, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hérivaux, A.; So, Y.S.; Gastebois, A.; Latgé, J.P.; Bouchara, J.P.; Bahn, Y.S.; Papon, N. Major sensing proteins in pathogenic fungi: The hybrid histidine kinase family. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defosse, T.A.; Sharma, A.; Mondal, A.K.; Dugé de Bernonville, T.; Latgé, J.P.; Calderone, R.; Giglioli-Guivarc, N.; Courdavault, V.; Clastre, M.; Papon, N. Hybrid histidine kinases in pathogenic fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 95, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Martínez, F.; Eixerés, L.; Zamora-Caballero, S.; Casino, P. Structural and functional insights underlying recognition of histidine phosphotransfer protein in fungal phosphorelay systems. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.H.; Gumilang, A.; Kim, M.J.; Han, J.H.; Kim, K.S. A PAS-containing histidine kinase is required for conidiation, appressorium formation, and disease development in the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. Mycobiology 2019, 47, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuffle, E.C.; Johnson, M.S.; Watts, K.J. PAS domains in bacterial signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 61, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.L.; Zhulin, I.B. PAS domains: Internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 479–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liu, N.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, C.; Gao, Q. The sensor proteins BcSho1 and BcSln1 are involved in, though not essential to, vegetative differentiation, pathogenicity and osmotic stress tolerance in Botrytis cinerea. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.X.; Huang, M.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, C.C. Control of cell size by c-di-GMP requires a two-component signaling system in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04228-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.; de Larrinoa, I.F.; Tudzynski, B. Calcineurin-responsive zinc finger transcription factor CRZ1 of Botrytis cinerea is required for growth, development, and full virulence on bean plants. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segmüller, N.; Ellendorf, U.; Tudzynski, B.; Tudzynski, P. BcSAK1, a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase, is involved in vegetative differentiation and pathogenicity in Botrytis cinerea. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Campbell, M.; Murphy, J.; Lam, S.; Xu, J.R. The BMP1 gene is essential for pathogenicity in the gray mold fungus Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000, 13, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Li, X.; Wu, W.; Luo, W.; Wu, Y.; Brosché, M.; Overmyer, K. Ectopic expression of BOTRYTIS SUSCEPTIBLE1 reveals its function as a positive regulator of wound-induced cell death and plant susceptibility to Botrytis. Plant Cell. 2022, 34, 4105–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Dalmais, B.; Morgant, G.; Viaud, M. Screening of a Botrytis cinerea one-hybrid library reveals a Cys2His2 transcription factor involved in the regulation of secondary metabolism gene clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 52, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmais, B.; Schumacher, J.; Moraga, J.; Le Pecheur, P.; Tudzynski, B.; Collado, I.G.; Viaud, M. The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kan, J.A.; Stassen, J.H.; Mosbach, A.; Van Der Lee, T.A.; Faino, L.; Farmer, A.D.; Papasotiriou, D.G.; Zhou, S.; Seidl, M.F.; Cottam, E.; et al. A gapless genome sequence of the fungus Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Free, S.J. Fungal cell wall organization and biosynthesis. Adv. Genet. 2013, 81, 33–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, K.; Yahya, S.; Jadoon, M.; Yaseen, E.; Nadeem, Z. Strategies for cadmium remediation in nature and their manipulation by molecular techniques: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 10259–10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipke, P.N.; Ovalle, R. Cell wall architecture in yeast: New structure and new challenges. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 3735–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Arias, M.J.; Dementhon, K.; Defosse, T.A.; Foureau, E.; Courdavault, V.; Clastre, M.; Le Gal, S.; Nevez, G.; Le Govic, Y.; Bouchara, J.-P.; et al. Group X hybrid histidine kinase Chk1 is dispensable for stress adaptation, host-pathogen interactions and virulence in the opportunistic yeast Candida guilliermondii. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Pérez, I.; Sánchez, O.; Kawasaki, L.; Georgellis, D.; Aguirre, J. Response regulators SrrA and SskA are central components of a phosphorelay system involved in stress signal transduction and asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoto, F.; Noriyuki, O.; Akihiko, I.; Ron, U.; Koki, H.; Isamu, Y. Sensitivity to phenylpyrrole fungicides and abnormal glycerol accumulation in os and cut mutant strains of Neurospora crassa. J. Pestic. Sci. 2000, 25, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lamm, R.; Pillonel, C.; Lam, S.; Xu, J.R. Osmoregulation and fungicide resistance: The Neurospora crassa os-2 gene encodes a HOG1 mitogen-activated protein kinase homologue. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, Y.S. Master and commander in fungal pathogens: The two-component system and the HOG signaling pathway. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 2017–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, C.; Izumitsu, K. Two-component signaling system in filamentous fungi and the mode of action of dicarboximide and phenylpyrrole fungicides. Fungicides 2010, 1, 523–538. [Google Scholar]

- Corran, A.; Knauf-Beiter, G.; Zeun, R. Fungicides acting on signal transduction. In Modern Crop Protection Compounds; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; pp. 561–580. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Yang, Q.; Sundin, G.W.; Li, H.; Ma, Z. The mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase BOS5 is involved in regulating vegetative differentiation and virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2010, 47, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diskin, S.; Sharir, T.; Feygenberg, O.; Maurer, D.; Alkan, N. Fludioxonil-A potential alternative for postharvest disease control in mango fruit. Crop Prot. 2019, 124, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, T.; Flanagan, H.; Faykin, A.; Seto, A.G.; Mattison, C.; Ota, I. Two protein-tyrosine phosphatases inactivate the osmotic stress response pathway in yeast by targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase, Hog1. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 17749–17755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilani, J.; Fillinger, S. Phenylpyrroles: 30 years, two molecules and (nearly) no resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, K.; Randhawa, A.; Kaur, H.; Mondal, A.K.; Hohmann, S. Fungal fludioxonil sensitivity is diminished by a constitutively active form of the group III histidine kinase. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2417–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M.M.; Enderlin, C.S.; Selitrennikoff, C.P. The osmotic-1 locus of Neurospora crassa encodes a putative histidine kinase similar to osmosensors of bacteria and yeast. Curr. Microbiol. 1997, 34, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, L.A.; Borkovich, K.A.; Simon, M.I. Hyphal development in Neurospora crassa: Involvement of a two-component histidine kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 3416–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.K.; Renault, S.; Selitrennikoff, C.P. Molecular dissection of alleles of the osmotic-1 locus of Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2002, 35, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, J.L.; de Valoir, T.; Dwyer, N.D.; Winter, E.; Gustin, M.C. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science 1993, 259, 1760–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshima, M.; Banno, S.; Okada, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Kimura, M.; Ichiishi, A.; Yamaguchi, I. Survey of mutations of a histidine kinase gene BcOS1 in dicarboximide-resistant field isolates of Botrytis cinerea. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2006, 72, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, N.; Tokai, T.; Nishiuchi, T.; Takahashi-Ando, N.; Fujimura, M.; Kimura, M. Involvement of the osmosensor histidine kinase and osmotic stress-activated protein kinases in the regulation of secondary metabolism in Fusarium graminearum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 363, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Fang, A.; Tian, B.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Bi, C. Binding mode and molecular mechanism of the two-component histidine kinase Bos1 of Botrytis cinerea to Fludioxonil and Iprodione. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Michailides, T.J.; Ma, Z. Involvement of a putative response regulator Brrg-1 in the regulation of sporulation, sensitivity to fungicides, and osmotic stress in Botrytis cinerea. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, D.; Matsubayashi, Y.; Marui, J.; Furukawa, K.; Yamashino, T.; Kanamaru, K.; Kato, M.; Abe, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Mizuno, T. Characterization of the NikA histidine kinase implicated in the phosphorelay signal transduction of Aspergillus nidulans, with special reference to fungicide responses. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianos, G.; Piombo, E.; Dubey, M.; Karlsson, M.; Karaoglanidis, G.; Tzelepis, G. Transcriptomic and functional analyses on a Botrytis cinerea multidrug-resistant (MDR) strain provides new insights into the potential molecular mechanisms of MDR and fitness. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SVermeulen, T.; Schoonbeek, H.; De Waard, M.A. The ABC transporter BcatrB from Botrytis cinerea is a determinant of the activity of the phenylpyrrole fungicide fludioxonil. Pest Manag. Sci. Former. Pestic. Sci. 2001, 57, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Yu, C.; Bi, Q.; Zhang, J.; Hao, J.; Liu, P.; Liu, X. Procymidone application contributes to multidrug resistance of Botrytis cinerea. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Yan, J.; Duan, L. Transcriptomic analysis of resistant and wild-type Botrytis cinerea isolates revealed fludioxonil-resistance mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S. Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 300–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B. The two-component system regulators BcSkn7 and BcBrrg1 are essential for stress response and virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2018, 115, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, J.L.; Gustin, M.C. Hog1: 20 years of discovery and impact. Sci. Signal. 2014, 7, re7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Gu, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Noman, M.; Wang, J.; Li, L. BcHK71 and BcHK67, Two-Component Histidine Kinases, Regulate Conidial Morphogenesis, Glycerol Synthesis, and Virulence in Botrytis cinerea. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120850

Wang M, Gu S, Guo J, Wu J, Wang X, Noman M, Wang J, Li L. BcHK71 and BcHK67, Two-Component Histidine Kinases, Regulate Conidial Morphogenesis, Glycerol Synthesis, and Virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):850. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120850

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Mengjing, Shiyu Gu, Jian Guo, Jingyu Wu, Xinhe Wang, Muhammad Noman, Jiaoyu Wang, and Ling Li. 2025. "BcHK71 and BcHK67, Two-Component Histidine Kinases, Regulate Conidial Morphogenesis, Glycerol Synthesis, and Virulence in Botrytis cinerea" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120850

APA StyleWang, M., Gu, S., Guo, J., Wu, J., Wang, X., Noman, M., Wang, J., & Li, L. (2025). BcHK71 and BcHK67, Two-Component Histidine Kinases, Regulate Conidial Morphogenesis, Glycerol Synthesis, and Virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120850