Bovine Mastitis-Derived Bacillus cereus in Inner Mongolia: Strain Characterization, Virulence Factor Identification, and Pathogenicity Validation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of Milk-Derived Bacteria

2.2. Determination of Antimicrobial Susceptibility

2.3. Detection of Virulence Genes

2.4. Construction of Mouse Mastitis Model

2.5. Histological Analysis

2.6. Determination of Biochemical and Oxidative Stress Parameters in Serum and Liver Tissue

2.7. RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR Analysis

2.8. Western-Blotting Analysis

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Bacterial from Bovine Clinical Mastitis

3.2. Phenotypic Drug Susceptibility of B. cereus Isolated from Bovines with Clinical Mastitis

3.3. Carriage of Virulence Genes in B. cereus

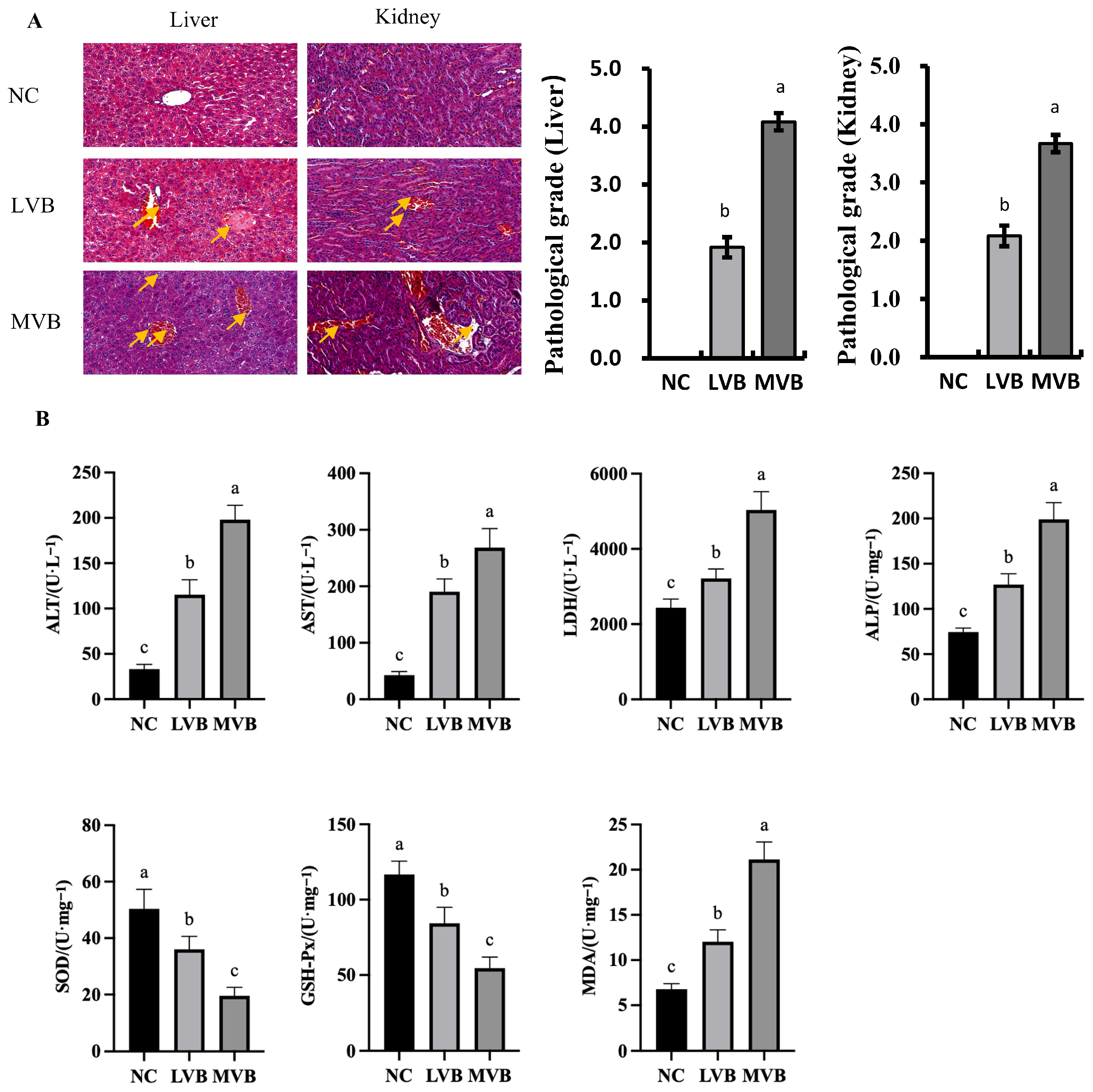

3.4. B. cereus Induces Histopathological Damage in the Liver and Kidney and Inflammatory Gene Expression in the Liver

3.5. Levels of Biochemical Parameters in Plasma of Mice Induced by B. cereus

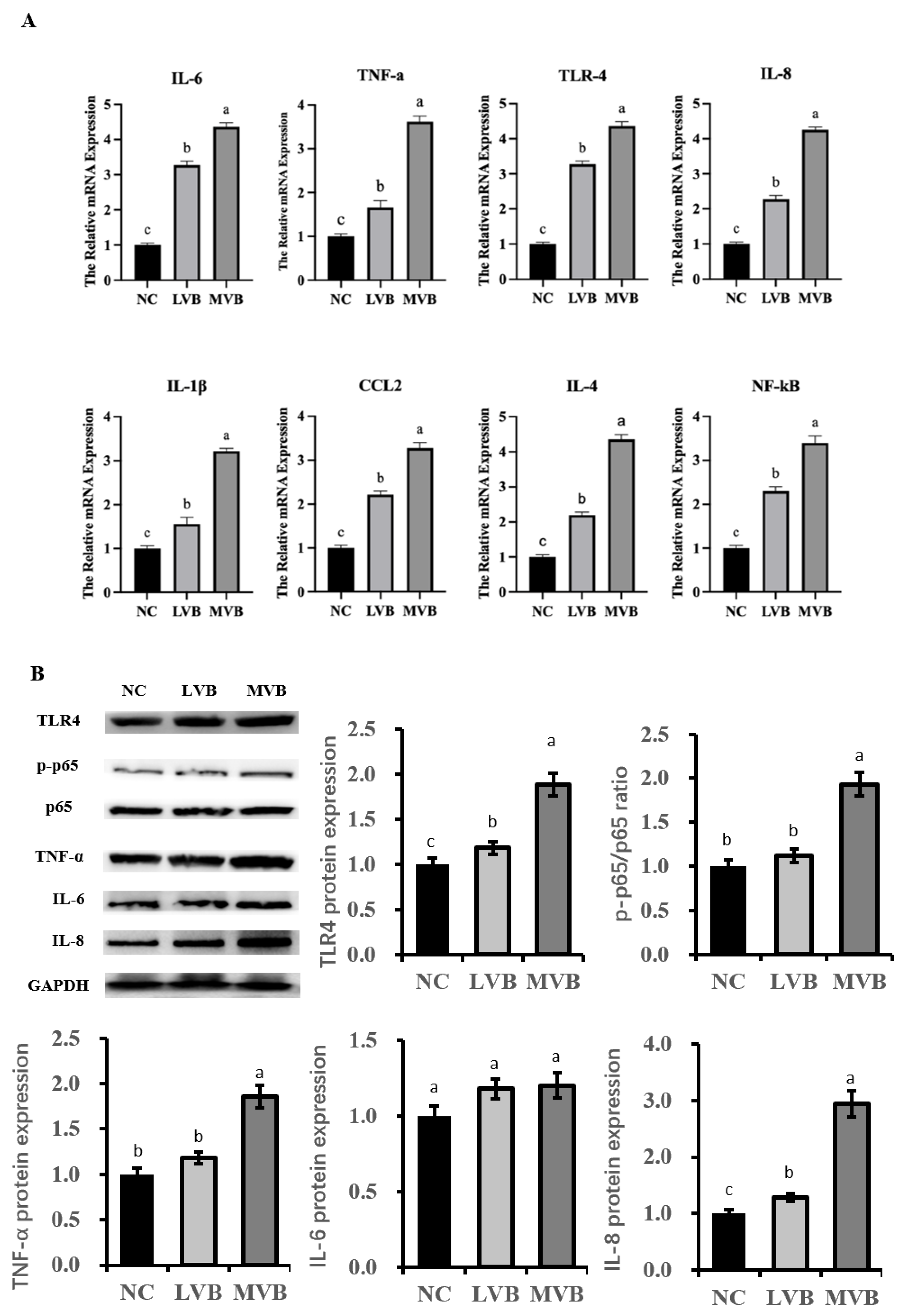

3.6. The Inducible Effect of B. cereus on the Expression of Inflammatory Genens and Proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cvetnić, L.; Samardžija, M.; Duvnjak, S.; Habrun, B.; Cvetnić, M.; Jaki Tkalec, V.; Đuričić, D.; Benić, M. Multi Locus Sequence Typing and spa Typing of Staphylococcus Aureus Isolated from the Milk of Cows with Subclinical Mastitis in Croatia. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Wang, J.; Luoreng, Z.; Wang, X.; Wei, D.; Yang, J.; Hu, Q.; Ma, Y. Progress in Expression Pattern and Molecular Regulation Mechanism of LncRNA in Bovine Mastitis. Animals 2022, 12, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, B.; Liu, N.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Zou, Y. Map of Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Targets Mitochondria and Triggers DRP-1-Mediated Mitochondrial Fission and Cell Apoptosis in Bovine Mastitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraki, A.; Teklue, T.; Atsbha, T.; Tesfay, T.; Wayou, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Bovine Mastitis in Southern Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Int. 2021, 2021, 8831117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belay, N.; Mohammed, N.; Seyoum, W. Bovine Mastitis: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Bacterial Pathogens Isolated in Lactating Cows in Gamo Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Vet. Med. 2022, 13, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolini, A.B.; Prado, A.M.; Thyssen, P.J.; de Souza Ribeiro Mioni, M.; de Gouvea, F.L.R.; da Silva Leite, D.; Langoni, H.; de Figueiredo Pantoja, J.C.; Rall, V.M.; Guimarães, F.F.; et al. Prevalence of bovine mastitis-related pathogens, identified by mass spectrometry in flies (Insecta, Diptera) captured in the milking environment. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 75, 1232–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaas, I.C.; Zadoks, R.N. An update on environmental mastitis: Challenging perceptions. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65 (Suppl. S1), 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, J.; Ornelis, V.F.M.; Madder, A.; Rajkovic, A. Bacillus cereus food intoxication and toxicoinfection. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3719–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenfors Arnesen, L.P.; Fagerlund, A.; Granum, P.E. From soil to gut: Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 579–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Hu, Q.; Xu, F.; Ding, S.Y.; Zhu, K. Characterization of Bacillus cereus in Dairy Products in China. Toxins 2020, 12, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Q.; Liu, N.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, J.; Wang, J. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 attenuates foodborne Bacillus cereus-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activity in bovine mammary epithelial cells by protecting intercellular tight junctions. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.A.; Jian, J.; Beno, S.M.; Wiedmann, M.; Kovac, J. Intraclade Variability in Toxin Production and Cytotoxicity of Bacillus cereus Group Type Strains and Dairy-Associated Isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02479-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, R.; Jessberger, N.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Märtlbauer, E.; Granum, P.E. The Food Poisoning Toxins of Bacillus cereus. Toxins 2021, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, J.; Fei, P.; Feng, H.; Wang, Y.; Ali, M.A.; Li, S.; Jing, H.; Yang, W. Prevalence, molecular characterization, and antibiotic susceptibility of Bacillus cereus isolated from dairy products in China. J. Dairy. Sci. 2020, 103, 3994–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granum, P.E. Spotlight on Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364, fnx071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Peraro, M.; van der Goot, F.G. Pore-forming toxins: Ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Didier, A.; Dietrich, R.; Heilkenbrinker, U.; Waltenberger, E.; Jessberger, N.; Märtlbauer, E.; Benz, R. Formation of small transmembrane pores: An intermediate stage on the way to Bacillus cereus non-hemolytic enterotoxin (Nhe) full pores in the absence of NheA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 469, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessberger, N.; Dietrich, R.; Schwemmer, S.; Tausch, F.; Schwenk, V.; Didier, A.; Märtlbauer, E. Binding to The Target Cell Surface Is The Crucial Step in Pore Formation of Hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Toxins 2019, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessberger, N.; Kranzler, M.; Da Riol, C.; Schwenk, V.; Buchacher, T.; Dietrich, R.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Märtlbauer, E. Assessing the toxic potential of enteropathogenic Bacillus cereus. Food Microbiol. 2019, 84, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücking, G.; Frenzel, E.; Rütschle, A.; Marxen, S.; Stark, T.D.; Hofmann, T.; Scherer, S.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Ces locus embedded proteins control the non-ribosomal synthesis of the cereulide toxin in emetic Bacillus cereus on multiple levels. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Li, D.; Xu, Y.; Wei, M.; Chen, Q.; Deng, Y.; Wen, J. Chronic cereulide exposure causes intestinal inflammation and gut microbiota dysbiosis in mice. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, X.; Qu, T.; Liang, L.; Ji, Q.; Chen, Y. Insight into Bacillus cereus Associated with Infant Foods in Beijing. Foods 2022, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, S.; Heller, E.D.; Krifucks, O.; Sela, S.; Hammer-Muntz, O.; Leitner, G. Identification of a bovine mastitis Escherichia coli subset. Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 132, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratory Handbook on Bovine Mastitis; National Mastitis Council: New Prague, MN, USA, 2017.

- Frank, J.A.; Reich, C.I.; Sharma, S.; Weisbaum, J.S.; Wilson, B.A.; Olsen, G.J. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests, 14th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Malvern, PA, USA, 2024.

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, J.; Loor, J.J. Methionine and valine activate the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 pathway through heterodimeric amino acid taste receptor (TAS1R1/TAS1R3) and intracellular Ca(2+) in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J. Dairy. Sci. 2018, 101, 11354–11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chu, S.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Xu, T.; Mao, Y.; Loor, J.J.; Yang, Z. MiR-16a Regulates Milk Fat Metabolism by Targeting Large Tumor Suppressor Kinase 1 (LATS1) in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11167–11178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, G.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, F.; Xie, G. Protective effects of melatonin on lipopolysaccharide-induced mastitis in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paape, M.J.; Bannerman, D.D.; Zhao, X.; Lee, J.W. The bovine neutrophil: Structure and function in blood and milk. Vet. Res. 2003, 34, 597–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Kwarteng, J.; Wuni, A.; Akabanda, F.; Tano-Debrah, K.; Jespersen, L. Prevalence, virulence factor genes and antibiotic resistance of Bacillus cereus sensu lato isolated from dairy farms and traditional dairy products. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wu, X.; Cao, H.; Pei, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Z. The Characteristics of Multilocus Sequence Typing, Virulence Genes and Drug Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Cattle in Northern Jiangsu, China. Animals 2022, 12, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xu, T. Isolation of Pathogenic Bacteria from Dairy Cow Mastitis and Correlation of Biofilm Formation and Drug Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Jiangsu, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Ding, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S.; Yu, P.; Liu, C.; Kong, L.; Feng, Z.; et al. Prevalence, Virulence Genes, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Genetic Diversity of Bacillus cereus Isolated From Pasteurized Milk in China. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, L.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, H.; Cai, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z. Virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance of Bacillus cereus in prepackaged pastries sold in Taizhou from 2020 to 2022. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2024, 53, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.H.; Aref, N.E.; Ibrahim, E.S. Phenotypic diagnosis and genotypic identification of Bacillus cereus causing subclinical mastitis in cows. Vet. World 2023, 16, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yu, P.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Guo, H.; Liu, C.; Kong, L.; Yu, L.; Wu, S.; Lei, T.; et al. A Study on Prevalence and Characterization of Bacillus cereus in Ready-to-Eat Foods in China. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Xie, Q.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Feng, H. The prevalence and characterization of Bacillus cereus isolated from raw and pasteurized buffalo milk in southwestern China. J. Dairy. Sci. 2021, 104, 3980–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, Y.; Effarizah, M.E. Prevalence, toxigenic profiles, multidrug resistance, and biofilm formation of Bacillus cereus isolated from ready-to eat cooked rice in Penang, Malaysia. Food Control 2021, 121, 107553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Märtlbauer, E.; Dietrich, R.; Luo, H.; Ding, S.; Zhu, K. Multifaceted toxin profile, an approach toward a better understanding of probiotic Bacillus cereus. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 49, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Cui, J.; Cui, T.; Guo, H.; Ono, H.K.; Park, C.H.; Okamura, M.; Nakane, A.; Hu, D.L. Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Is an Important Virulence Factor for Mastitis. Toxins 2019, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; Dietrich, R.; Märtlbauer, E.; Cao, J.; Ding, S.; Zhu, K. Characterization of Bacillus cereus isolates from local dairy farms in China. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Ye, L.; Xiong, W.; Hu, Q.; Chen, K.; Sun, R.; Chen, S. Prevalence and genomic characterization of the Bacillus cereus group strains contamination in food products in Southern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 170903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wei, Y.; Shi, L.; Khan, M.Z.; Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y. Genome-wide DNA methylation pattern in a mouse model reveals two novel genes associated with Staphylococcus aureus mastitis. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, D.; Redmon, N.; Mazzio, E.; Soliman, K.F. Apigenin inhibits TNFα/IL-1α-induced CCL2 release through IKBK-epsilon signaling in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.M.; Lemos, H.P.; Grespan, R.; Napimoga, M.H.; Dal-Secco, D.; Freitas, A.; Cunha, T.M.; Verri, W.A., Jr.; Souza-Junior, D.A.; Jamur, M.C.; et al. A crucial role for TNF-alpha in mediating neutrophil influx induced by endogenously generated or exogenous chemokines, KC/CXCL1 and LIX/CXCL5. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y.; Mikami, O.; Yoshioka, M.; Motoi, Y.; Ito, T.; Ishikawa, Y.; Fuse, M.; Nakano, K.; Yasukawa, K. Elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) activities in the sera and milk of cows with naturally occurring coliform mastitis. Res. Vet. Sci. 1997, 62, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Ambatipudi, K. Mammary microbial dysbiosis leads to the zoonosis of bovine mastitis: A One-Health perspective. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 97, fiaa241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Farm A | Farm B | Farm C | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | None | Bacteria | None | Bacteria | None | Bacteria | None | |

| Milk Samples (No.) | 52 | 0 | 46 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 106 | 2 |

| Rate (%) | 48.15 | 0 | 42.59 | 1.86 | 7.4 | 0 | 98.14 | 1.86 |

| Name of Bacteria | Number of Detections | Detection Rate | Farm A | Farm B | Farm C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus cereus | 104 | 30.58% | 57 | 39 | 8 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 74 | 21.76% | 38 | 30 | 6 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 26 | 7.65% | 12 | 10 | 4 |

| Rhizobium | 26 | 7.65% | 24 | 2 | 0 |

| Bacillus sphaericus | 14 | 4.12% | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| Bacillus pusillus | 12 | 3.54% | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Pseudomonas | 8 | 2.35% | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 4 | 1.17% | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Copperhead | 4 | 1.17% | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 2 | 0.59% | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthrobacter | 2 | 0.59% | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Actinobacillus | 2 | 0.59% | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 62 | 18.24% | 38 | 16 | 8 |

| Total | 340 | 100% | 197 | 116 | 27 |

| Carrying Virulence Genes | Number of B. cereus Strains | Detection Rate |

|---|---|---|

| nheA | 104 | 100% |

| nheB | 104 | 100% |

| entFM | 104 | 100% |

| nheC | 102 | 98.1% |

| cytK | 32 | 30.8% |

| hblC | 42 | 40.4% |

| hblA | 38 | 36.5% |

| hblD | 22 | 21.2% |

| bceT | 38 | 36.5% |

| ces | 26 | 25% |

| EM1 | 26 | 25% |

| Carrying Virulence Genes | Amount of B. cereus Strains |

|---|---|

| nheA, nheB, entFM | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC | 10 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA | 4 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblC | 8 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, cytK | 6 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, bceT | 16 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, cytK, hblC | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, hblC | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblC, hblD | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblC, cytK | 4 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, cytK, bceT | 6 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, ces, EM1 | 8 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, bceT, ces, EM1 | 6 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, hblC, hblD | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, hblC, cytK | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblC, hblD, cytK | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, bceT, ces, EM1 | 4 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblC, hblD, ces, EM1 | 8 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, hblC, cytK, bceT | 2 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, hblC, hblD, cytK | 4 |

| nheA, nheB, entFM, nheC, hblA, hblC, hblD, cytK, bceT | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, C.; Vivian, K.H.; Fan, S.; He, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Xu, T. Bovine Mastitis-Derived Bacillus cereus in Inner Mongolia: Strain Characterization, Virulence Factor Identification, and Pathogenicity Validation. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111057

Yu C, Vivian KH, Fan S, He X, Zhao J, Yang Z, Zhang K, Xu T. Bovine Mastitis-Derived Bacillus cereus in Inner Mongolia: Strain Characterization, Virulence Factor Identification, and Pathogenicity Validation. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(11):1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111057

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Chen, Kollie Helena Vivian, Shuangyuan Fan, Xiaojiao He, Jingwen Zhao, Zhangping Yang, Kai Zhang, and Tianle Xu. 2025. "Bovine Mastitis-Derived Bacillus cereus in Inner Mongolia: Strain Characterization, Virulence Factor Identification, and Pathogenicity Validation" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 11: 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111057

APA StyleYu, C., Vivian, K. H., Fan, S., He, X., Zhao, J., Yang, Z., Zhang, K., & Xu, T. (2025). Bovine Mastitis-Derived Bacillus cereus in Inner Mongolia: Strain Characterization, Virulence Factor Identification, and Pathogenicity Validation. Veterinary Sciences, 12(11), 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111057