1. Introduction

The evolution of wine consumption in the UK is described by important socio-economic trends in consumer behavior that emerged in the 1950s. This coincided with a growing awareness within the alcoholic beverages industry that there was the need for new product development to satisfy the increasingly sophisticated and aspirational consumer. From an almost negligible base of high-end demand through specialist wine merchants, which were located primarily in London, data published recently by the Wine and Spirit Trade Association (WSTA) shows that the UK is now the world’s sixth largest wine market. Some 60% of UK adults consume wine with the industry worth £6.6 bn in the supermarket sector (off-trade) and £4.2 bn in bars, pubs, and restaurants (on-trade) [

1]. International Wine & Spirit Research (IWSR) predicts that the UK will be second only to the US in terms of the value of still wine sales by the end of 2018 [

2].

Crucial in this post-World War II evolution was a new entry firm that, taking its cue from the sophistication embodied in the Champagne category, developed a viable alternative from UK home-made perry (pear), which was targeted specifically at women. Another established operator, with roots in the similarly evolving spirits industry, experimented with consumer profiling and used its growing influence to encourage its French suppliers to abandon hostility to ‘adulteration’ to align with the more traditional British taste for sweetness. Although many of the early brands from this era of marketing entrepreneurship are no longer important to the UK wine industry, their legacy is in educating the mass market to the virtues of wine.

In this article, I present a narrative historic account of the evolution of the UK wine market to inform the Special Issue’s broad theme of segmentation and differentiation through time and space. Utilizing a dataset of industry trade association information, regulatory documents, and secondary accounts of key new product launches, I highlight the early competitive struggle faced by wine as it sought wider legitimacy among UK consumers. Characterized by its origins in an alcoholic beverages industry that was controlled by the marketing and distribution platforms of the vertically-integrated UK brewers, and, as the domicile of the leading international spirits category, Scotch whisky, the UK is now one of the world’s leading consumers of wine by both volume and value. Anchoring the article in the emerging literature encompassing resource partitioning theory, and adjoining recent wine research that has described the convergence in consumption patterns across the major developed economies, I seek to answer two inter-related questions: How did a market controlled by deeply-embedded brewing interests cede legitimacy to wine consumption, mindful that the UK was—and remains—a negligible wine producer. Given that resource partitioning theory implies an evolution from mass market to highly-differentiated (craft) boundary products, why does UK wine consumption display the apparent reverse.

2. Theoretical Background

As a function of history and an array of socio-economic and cultural norms, countries have been classified as wine, beer, or spirits consumer markets. The ability to cultivate the originating crops from which alcohol is derived, in addition to factors, such as taxation, have been important in underpinning the historic specificity of aggregate alcohol consumption. Recent detailed research investigating consumption patterns across the European Union, with its extensive mix of cultures, languages and agricultural traditions, shows that a process of convergence in drinking habits started some 50 years ago, predating the formation of the single market and other structural changes within the European Union [

3]. Traditionally, consumer demand characteristics have been theorized largely from the perspective of industrial economics. The alcoholic beverages industry, and the beer industry specifically, has provided a rich empirical setting from which sophisticated consumer demand models have been proposed and tested, often with merger and antitrust policy [

4,

5,

6], or more general macroeconomic and demographic policy [

3,

7], implications in mind. However, the micro-foundations of such change, both within and across countries, remains largely under-explored.

Management scientists aligned to the broad disciplinary area of evolutionary economics, have sought to correct the ahistorical nature of the theory of consumer categories by incorporating aspects of path-dependency and historical context. In this research field, the alcoholic beverages industry has also featured prominently, with studies of, for example, the US and German brewing industries offering empirical support for the model of density-dependent legitimation and competition derived from Hannan and Freeman’s noted ecological theory of organizational change [

8,

9]. In this theoretical model when there are few organizations in a population or specific geographic location, an increase in their number (density) enhances the legitimacy of that form. In contrast, when organizations are abundant, increases in density lead to an intensity of competition, and ultimately, higher mortality. Aligned to this thesis, resource partitioning explains the rise of late-stage specialist segments within an industry as an (unexpected) outcome of consolidation among large generalist organizations as they compete for the largest consumer resource bases of the mass market [

10].

The wine industry, both within geographic locations, such as in the US, or within a more narrowly defined style of wines, has been an important empirical setting from which the theory of how categories and sub-categories emerge and gain authenticity has been extended. This has been utilized, for example, to explain the shift of consumption from ‘jug wine’ to ‘farm wineries’ in the US. Researchers have found that although mass market wine producers adopting a robust identity through brand proliferation coupled with higher advertising expenditures can succeed in breaching the boundaries between generalist and specialist categories [

11], analysis more generally has shown that an association with multiple categories causes producers to be perceived as poorer fits with category identities than specialized competitors [

12]. Niche producers, lacking the resources necessary for marketing and advertising campaigns, can nevertheless adopt novel approaches, such as incorporating their location as part of wine tourism and organized events, to successfully promote their products. By co-opting like-minded local competitors, intra-group values are developed and promoted to underpin what gains legitimacy as a social agreement or movement. This is not unlike the grassroots consumer pressure for choice within the US beer industry, that although by no means the only factor, has been an important catalyst in the burgeoning craft beer movement [

13].

At the macro level, the beer and wine industries have been utilized in studies seeking to analyze the effect of economic integration on consumption habits. Alcohol consumption is often attributed to different countries and cultures, as well as agricultural conditions, but there has been an evident convergence in drinking habits in most developed economies since the early 1960s. The combination of increased business and leisure travelling, the rise in the number of international retailers, the standardization of consumer policy regulations, and the trajectory of educational practice that promotes uniformity in attitudes and beliefs, have been important factors in promoting and accelerating the convergence of disparate cultures and social values [

14]. Patterns of behavior, such as the influence of parental habits on the next generation’s choice versus the impact of globalization on consumer spending power, have been modelled econometrically, with researchers seeking to understand more clearly what has driven the observable pattern of ‘wine-drinking’ countries drinking more beer and ‘beer-drinking’ countries drinking more wine [

15]. Notwithstanding the plethora of studies, research has tended to be limited to a specific region or group of high-income countries, or to just one or two types of alcohol. In the most extensive study to date, Holmes and Anderson lengthened the time series to incorporate the late nineteenth century for 11 high-income countries, and modelled a dataset comprising all countries for all types of beverage. These authors concluded there were strong, but not unequivocal indications of convergence in national alcohol consumption patterns across the world, recommending the addition of yet more variables in the analysis, such as consumer tax rates, per-capita incomes, and trade costs to better understand statistically the evolution of demand across time and space [

16].

At the individual consumer level, researchers consider anecdotally that wine preferences evolve over time as a function of experience and familiarity, although little is known about how confidence emerges to support experimentation. In countries where socio-cultural norms promote wine consumption as part of the normal course of everyday life, such as in family eating occasions, preferences are informed by multigenerational learning. This may moderate future experimentation, and it is known that prior wine knowledge tends to favor the consumption of red wine. Studies have investigated how education and training courses might influence consumption behavior. This demonstrates there is a propensity for hedonic (visual, aroma, flavor) ratings to increase significantly with education for white and rosé wines, and for consumer confidence to grow with experience for all wine types [

17]. This is consistent with other studies that have measured the geographical, cultural, historic and social components of authentic products, where hedonism is augmented by a consumer’s need for empowerment through their curiosity to learn about and visit the places of production, to participate in memorable events, and to enjoy unique and unrepeatable experiences [

18].

As a more recent phenomenon, social networks and wine clubs, with their opportunities for societal marketing strategies, are important platforms for increasing knowledge [

19]. Information from the UK has shown that consumption behavior varies depending on the level of involvement with the category. Brand name is of greater importance in the wine-buying decisions of low-involvement consumers, particularly when it is for a special occasion. Although high-involvement consumers are more inclined to use newspapers, magazines, the Internet, and wine books as their sources of information, word-of-mouth plays the most important role for both low- and high-involvement wine consumer decisions [

20]. In a series of novel auction-based experiments involving branded Californian wines, researchers found that participants with different wine knowledge adjusted their propensity to pay based on discovering new information, particularly when it was derived from expert ratings as opposed to general reputational information that is provided by appellations [

21]. The significance of subjective wine knowledge has been assessed and evaluated directly during winery visits with the objective of informing future marketing strategy. Consumers with higher subjective knowledge consumed and purchased wine more frequently, bought larger quantities of wine at a time, higher-priced wines, and drank red and/or dry wines more frequently [

22].

3. Data and Methodology

My article adopts a longitudinal narrative approach consonant with the general theme of ‘history as evaluating’ to uncover aspects of path-dependency, dynamics, and change that might otherwise remain under-appreciated. In seeking to illuminate how interactions with the institutional environment shape the evolution of markets and industries, it is situated in the broad realm of historical organization studies of the narrative style that privileges historical storytelling and argumentation over theorization [

23]. In this field of study, empiricists have sought to enrich organization studies by according it a longitudinal perspective, while bringing a narrative approach to business history research by employing a research methodology that was designed to highlight the importance of the historical context for studying business behavior [

24]. The historical approach is a counterbalance to the cross-sectional studies more typical in social science, where ‘a reduction in complexity is needed to study relations between a selective set of variables’ [

25]. Economists with an interest in the beverages market have drawn attention to the (over) simplifying restrictive assumptions in much econometric analysis, for example, that the level of consumption is the simple sum of the per capita consumption of all categories as if they are perfect substitutes, when empirical evidence is sparse regarding the structural composition of consumption [

7], let alone how and why this might change over time.

In keeping with the approach adopted by business historians utilizing narrative methodology to integrate an ‘interpretation of the past, an understanding of the present, and a guideline to the future’, I engage with a wider set of sources, including official and legal archive, newspapers, and other contemporaneous data [

26]. Data that has been sourced and evaluated includes that of the British Beer & Pub Association (BBPA), a subscription only service, containing data sourced from UK government statistics and other information providers. The Scotch Whisky Association (SWA), and the Wine and Spirit Trade Association (WSTA), provide comprehensive annual statistical reports and other periodic publications that are free to view online to assist the public in the understanding of trends in consumption in the UK alcoholic beverages markets. Production might ordinarily be expected to feature in such an analysis, as has been the case in many other studies of the evolution of consumption [

3,

7]. However, as discussed below in more detail, UK wine production is ‘a cottage industry’, accounting for less than one percent of total wine market size notwithstanding a doubling of acreage in the past seven years [

2].

Given the historical incidence of industry consolidation and regulatory intervention in the UK brewing industry that spawned the UK wine market’s growth, there is a legacy of merger and antitrust documentation from a selection of inquiries by the UK’s former Monopolies Commission with their associated embedded data, which have useful information concerning the evolution of the wine industry in the UK. All official UK regulatory documents are free to view at The National Archives, Kew, London, and are available to order as a printed version. Finally, specific contemporaneous press commentary that has informed the discussion of specific marketing programs is referenced in the text.

4. The Emergence of the UK Wine Market

As a function of history and their wider infiltration into the social and political fabric of the UK, the major UK brewers came to determine domestic alcohol consumption habits as a function of the control of distribution into the retail public house and off license trade. The brewers’ unique vertically-integrated ownership structure evolved over two centuries into a complex monopoly that is centred on what were referred to as the ‘Big 6’. The industry was the subject of two detailed antitrust inquiries in 1969 and 1989, which led ultimately to the forced dismantling of the vertical tie during the 1990s under legislation referred to as the ‘Beer Orders’ [

27].

Prior to World War II, the UK brewers had interests in the wines and spirits trade, but only to the extent that they arranged the supply of these beverages to the public houses they owned and managed directly. Their tied tenanted pubs were free to contract directly with distillers and wine merchants and importers. During, and in the immediate aftermath of, the War, when supply restrictions were in place, tied tenants were unable to source wines and spirits supplies directly, and they solicited the assistance of the major brewers in sourcing such supplies. Having therefore gained a larger distributive foothold, the brewers entered the upstream production of wines and spirits directly in the late 1950s. Initially, this focused largely on the bulk buying and registration of supplies of whisky, gin, sherry, port, brandy and rum for listing as their own ‘house brands’ for sale within their pub estates. This became increasingly accompanied by onerous supply obligations on their tenants; in the antitrust inquiry of 1969, the greater volume of complaints from tenants emanated from the tying of wines and spirits (as opposed to beer), particularly the brewers’ promotion of their house brands [

28].

By the late 1960s, the brewers had extended their reach to established and dedicated wines and spirits producers through acquisition. Allied Breweries, one of the Big 6 brewers, and owner of Grants of St. James’s Ltd. (London, UK) (a wholesale wine and spirit merchant) and Victoria Wine Company Ltd. (London, UK) (a national chain of wines and spirits retail shops), acquired brand owner Showerings, Vine Products and Whiteway’s Ltd. (Shepton Mallet, Somerset, UK) in 1968, making it the largest manufacturer, wholesaler, and retailer of wines and spirits in the UK, and one of the largest in Europe [

29]. During 1968 Watney Mann, a second Big 6 brewer, became a major shareholder in International Distillers and Vintners (IDV), which would go on to become the driving force behind the internationalization success of its ultimate owner, Grand Metropolitan, during the 1980s. That the UK brewers were active in experimenting across the beverage spectrum, not just in brewing activities, is evident in the extensive strategic actions of Whitbread, another Big 6 brewer [

30].

One of the major socio-economic factors that underpinned the brewers’ interest in carving an increasing involvement in the wine market was recognition of the growing influence of women as consumers of alcohol. The traditional UK public house was aligned to the needs of heavy-industry male workers who favored beer at the end of a day’s manual work. However, once post-War reconstruction was completed, the UK returned to the trajectory of industrial decline. Concurrently, women were entering the workforce in greater numbers, and with their own money to spend, demanded variety in both products sold and types of formats in the all-important on-trade [

31]. With the accompanying trend towards casual dining, public houses were charged with the task of catering to the demands of both women and families or face eventual eradication. As UK consumers were also now able to travel abroad for annual summer holidays, particularly to close neighbors France, Spain, and Italy, new-found cosmopolitism in leisure activities meant that wine consumption gained significant traction. As

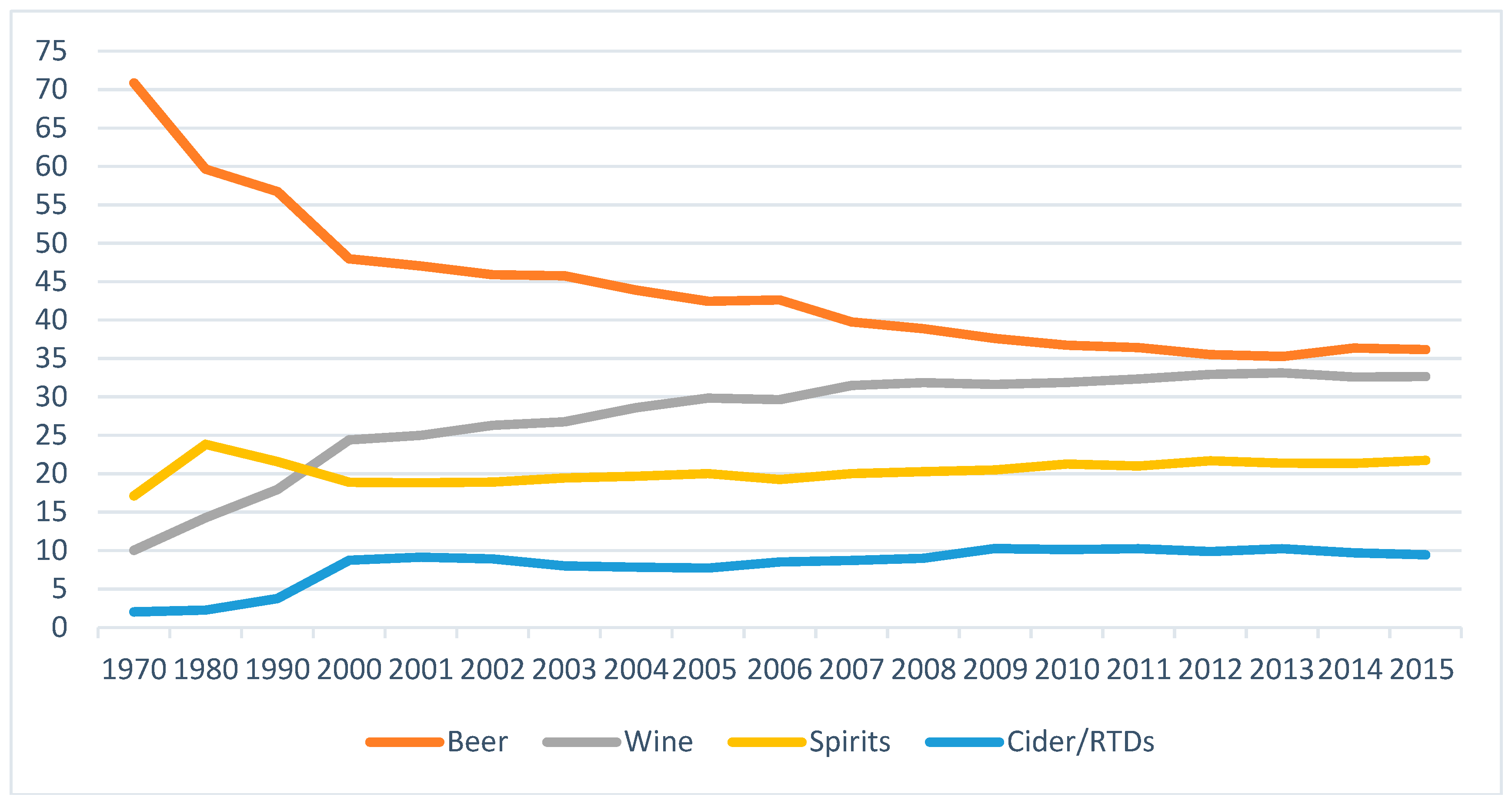

Figure 1 shows, a steep rise in the consumption of wine was matched by the precipitous decline in beer consumption as the 1980s approached.

Given that the UK brewers, specifically the Big 6, accounted for the lion’s share of beer production, as manufacturers with an integrated supply chain, one might have anticipated they would have gravitated to wine production. Indeed, they evolved as spirits producers and marketers, as well as becoming the dominant players in soft drinks and mineral waters, albeit at different rates and through a range of ownership arrangements, including acquisitions, joint ventures and start-ups [

30]. The issue for wine production in the UK was, and remains, of how to commercialize wine production given the UK’s climate. Data is limited prior to the 1980s, but notwithstanding the consumption profiles shown in

Figure 1, UK annual wine production only increased from 21 k hectoliters to 31 k hectoliters between 1989 and 2016, according to Wines of Great Britain (WineGB), which is the national organization that represents grape growers and winemakers [

32]. This is negligible in the context of UK wine consumption of some 8.5 m hectoliters [

2]. WineGB estimates that 2100 people are currently employed full-time in the UK wine production industry. In contrast, BBPA statistics estimate employment of 9400 in spirits production, 15,800 in beer production, and 486,000 in public houses and bars, albeit the latter is a combination of full- and part-time staff.

5. Key Milestones in Legitimizing the Wine Category

An interesting and informative example of how an entirely new category was created around one highly-marketed brand is found in the UK’s early answer to Champagne. Babycham, unlike the name it conjures, was neither an authentic European product, nor even wine, as it was derived from UK-sourced pear juice concentrate. Launched nationally in the early 1950s, Babycham was one of the first alcoholic drinks marketed directly to women. With the tagline, ‘The genuine Champagne Perry: The Babycham bottle fills a champagne glass’, it portrayed a glamorous post-War world with its allusion of sophistication to which most women could relate, albeit indirectly, in watching films and reading magazines [

33]. Babycham was developed by Somerset brewer, Francis Showering. Somerset is a UK county where the pear-derived perry had been produced for centuries alongside the more popular and better-known apple beverage, cider. The brand’s popularity peaked in the 1970s, shortly after its acquisition and incorporation into the Allied Breweries portfolio of interests. TV advertising was used to animate the iconic baby deer logo alongside a highly glamorous persona with ‘diamond sparkle’. Tastes were starting to change, however, and Babycham was eclipsed by other new products and the less successful marketing support of a series of new owners after Allied Breweries sold the brand. Attempts to rejuvenate it were unsuccessful. The removal of the original 1950s styling and targeting in a £3.5 m relaunch in 1993 was followed by a second £1.5 m relaunch in 1997 aimed at re-established it with young women, including the promotion of the iconic deer and trademark green stubby bottle packaging that had been integral to the initial brand proposition [

34,

35].

As mentioned above, the UK brewers were increasingly aware that their core beer market was in structural decline. They made several strategic initiatives in the wines and spirits industry, largely in the case of wine, based on new product introductions from brands in their ‘house brand’ portfolios. Examples included the Allied Breweries’ Nicolas brand from its Grants of St James subsidiary, and Whitbread’s Spanish wine, Corrida. Although successful superficially—sales of still wine increased 90% in the seven years leading up to the 1969 antitrust inquiry—the introductions failed to gain traction outside the brewers’ tied estates. It was not until a more specific and dedicated marketing program with a product, as opposed to distribution focus, became apparent that the broader wine category made significant headway in mainstream UK consumption. Crucial to this change of emphasis was IDV, the firm that, as a subsidiary of Grand Metropolitan, became the key innovator in the UK wine industry. Its influential head of product development, Tom Jago, with success in establishing Baileys Irish Cream and Malibu as new products, turned attention to the emerging popularity of still wine [

36].

Early 1970s UK consumers considered France as synonymous with wine. Traditional upper-class educated consumers had sourced fine Burgundy and Bordeaux wines for generations from established wine merchants [

37,

38]. IDV’s objective was to develop a branded French wine for lower-class consumers whose entry and acceptance was hindered by limited branding, product information usually written in French, and wine that varied from vineyard to vineyard, and from year to year. Following blind tasting of a sweetened blend of wines that were sourced from Austria, Hungary, and Italy among an exclusively male sample group, IDV launched Le Piat D’Or in 1975. It was the catalyst for the subsequent explosion in wine drinking in the UK, with the brand also finding appeal in Canada and Japan. It displaced what had been the UK market leader, the German medium sweet white wine, Blue Nun, viewed as ‘the mainstay of the 1970s dinner party and national joke’ [

39].

Much of the success of Le Piat D’Or can be attributed to a catchy TV advertising campaign. With the tagline, ‘

Les Français adorent le Piat D’Or’, a beautiful young French woman introduced her English boyfriend to her wary father, whose approval was, however, secured by the gift of a bottle of Le Piat D’Or, with its distinctive and opulent red and gold labelling [

40]. Although the product was French in origin, it was, nonetheless, adulterated by the addition of grape juice to make it more palatable to UK consumer preference for sweetness. This had the added advantage of providing an opportunity to standardize the quality of the wine from year to year. Throughout the 1980s, le Piat D’Or was the UK’s biggest-selling branded wine, before French wine’s popularity succumbed to new entrants, such as Jacob’s Creek and E&J Gallo’s brands, from the UK’s former trading partners, Australia, New Zealand and the US.

6. Recent Trends

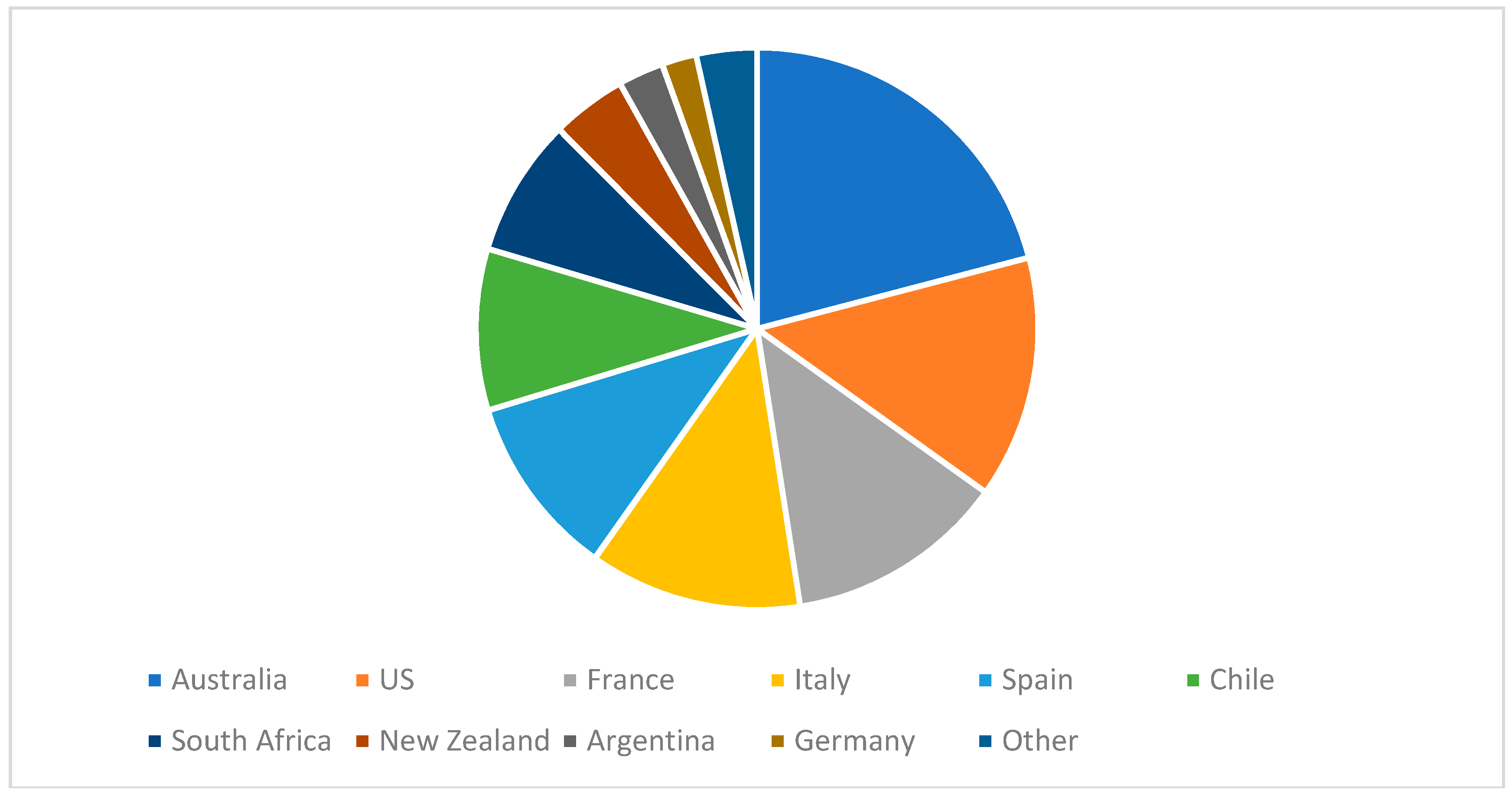

The UK market has changed dramatically since the 1980s and 1990s. As shown in

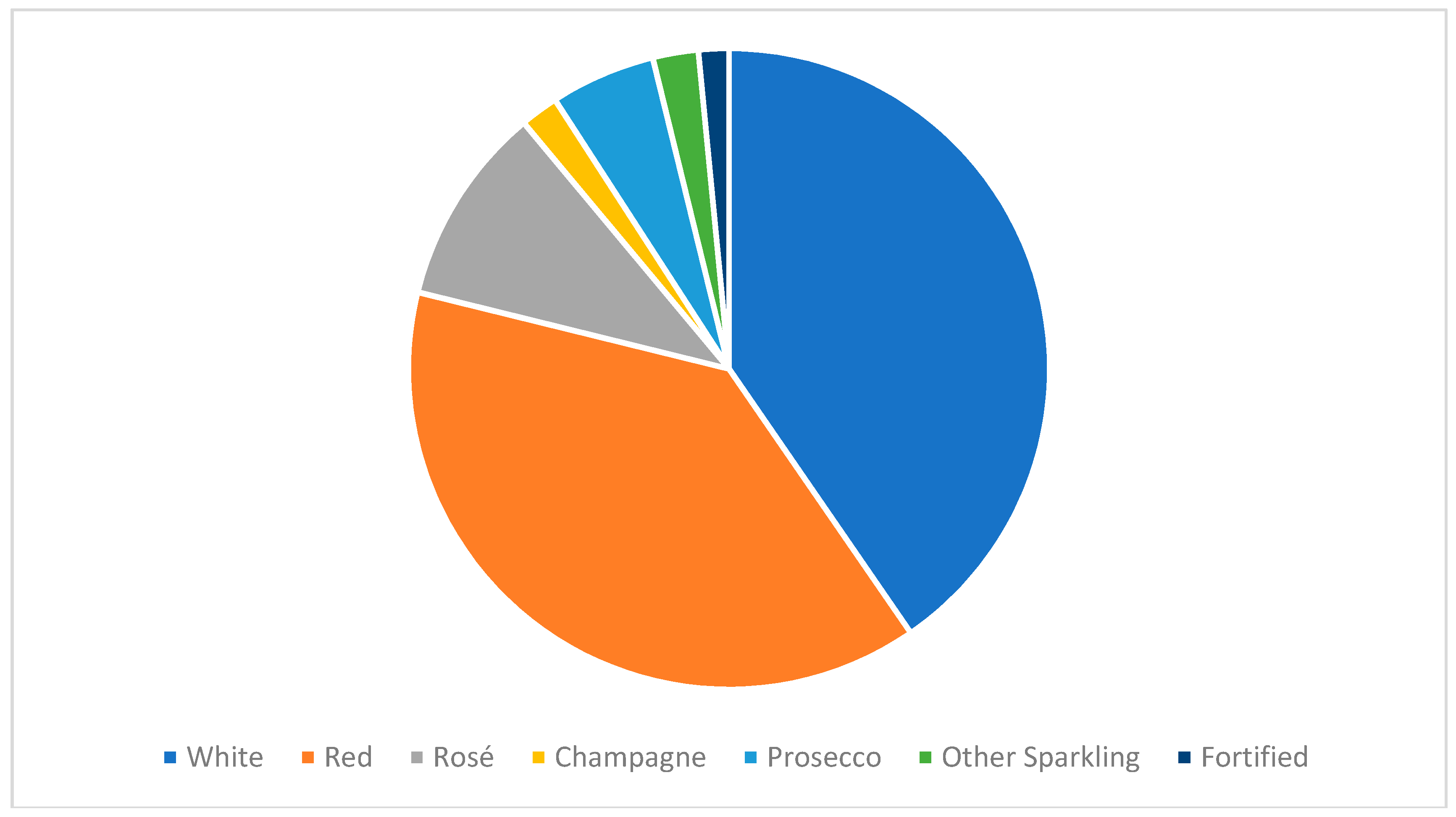

Figure 2, Australia is the most favored country of origin, having overtaken France in the mid-2000s. The status of Italy reflects the popularity of Italian sparkling wine, largely prosecco, as shown in

Figure 3. Most Australian wine is believed to be shipped in bulk for bottling and then distributing locally in the UK. The large differential in excise taxes between the UK and Europe, notwithstanding the overall objectives of the single market, means that there is significant cross-border trade, with up to 20% of the total UK wine market being comprised of such purchases for personal consumption, according to US government data [

2].

The UK is a relatively high excise tax regime when compared to its neighbors in Europe. Overall, excise taxes have risen sharply since 2000, but the burden has been heavier for wine, with duty increasing 80% between 2000 and 2016. Over the same period, beer duty rose 54% and spirits duty by just over 40%. This reflects growing pressure for a normalization of taxation across the various types of alcohol with the SWA specifically, engaging in intense lobbying for change. Wine benefits from favorable taxation across Europe and is not taxed at all in most wine-producing countries, such as Bulgaria, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. In its annual statistical reports, the SWA equilibrates the amount of duty on a normal measure of alcoholic drink containing the same amount of alcohol. It shows that, in 2015, the monetary value of duty was 18.37p for beer, 21.86p for wine, and 27.66p for Scotch whisky per measure.

Once the preserve of the better-educated or ‘upper class’ consumer, with a geographic profile largely mapping to the metropolitan and affluent southern parts of the UK, wine sales are spread far and wide across the population, as shown in

Figure 4.

On closer inspection, however, there are two key themes that emerge from the data. Firstly, although there is a wide spread of consumption across the regions, there is a legacy of under- or over-consumption of the various categories of alcohol that reflect Great Britain’s (the UK, excluding Northern Ireland, for which data was not available) history and socio-economic and cultural factors. Scotland, unsurprisingly, as the home of Scotch whisky, consumes a significantly higher proportion of spirits. The South West, being important in growing apples and pears, consumes a much higher amount of cider. Secondly, the significance of London in overall consumption generally, and wine consumption specifically, relative to its population requires further qualification. Regarding on-trade consumption, much of the population of the South & South East works in the environs of London, and consequently, it is reasonable to conclude that London’s over-consumption balances the South & South East’s evident under-consumption. London’s share of the value of consumption is even higher, accounting for 32% of on-trade value of sales of wine.

7. Concluding Remarks

I have presented an historical account of the evolution of the UK wine market to inform the Special Issue’s broad theme of segmentation and differentiation through time and space. Anchoring the article in the emerging literature of resource partitioning theory, and adjoining recent wine research that has identified a convergence in alcohol consumption patterns I sought answers to two inter-related questions: How did a market controlled by deeply-embedded brewing interests cede legitimacy to wine consumption, and, given that resource partitioning theory implies an evolution from mass market to highly-differentiated (craft) boundary products, why does UK wine consumption display the apparent reverse.

Once the preserve of the British upper classes, the emergence of wine in the UK mainstream can be traced to the post-War era, when entrepreneurship was directed at hitherto untapped demand; women. Babycham, which is a domestically-produced sparkling pear juice, established a cachet among young women, influenced by the sophistication and imagery of Champagne at a time of increasing prosperity and independence. The distributive power of the Big 6 vertically-integrated brewers, while enough to seed the still wine market with specially-developed ‘house brands’ as part of more general attempts to monopolize the beverages space [

28], did little to broaden the category overall. However, once renowned spirits industry innovator IDV, controlled by Big 6 brewing interests but with an inbuilt independence that promoted experimentation and entrepreneurship, turned its attention to wine, Le Piat D’Or emerged to educate the UK masses to the virtues of affordable French wine.

Notwithstanding the history of the UK as a beer and spirits-drinking market, reflecting at first instance the powerful legacy of the vertically-integrated brewing industry, in common with most other developed countries the UK, at least superficially, conforms to the convergence in alcohol consuming tastes evident in most other major developed markets [

3,

7]. Several reasons for this phenomenon have been forwarded under the general guise of ‘globalization’, including increased business and leisure travelling, the rise in the number of international retailers, and the standardization of consumer policy regulations, which have collectively accelerated the normalization of disparate cultures and social values [

14]. However, there remain gaps in understanding the micro-foundations driving these observations, with leading researchers recommending an extension of cross-sectional datasets to include additional variables such as consumer tax rates and per-capita incomes [

16]. As my historical study of one specific market has highlighted, the major demographic shift of women as large-scale independent consumers in the post-War era and the constant flux of changing drinking patterns in both on-trade and off-trade points of sale emanating from social trends and new multimedia platform opportunities [

19,

20,

22], require further inquiry employing broader multi-disciplinary methodological approaches and data sources.

The path to the UK becoming a wine-drinking country appears to somewhat contravene the tenets of resource partitioning theory, with its perspective of mass-market generic consumption being displaced by the popularity and legitimization of boundary products. In US beer, although restrained to some degree by basic institutional factors, such as the impact of federal and state legislation that stands in the face of apparent changing consumer demand for choice and authenticity [

13], the growth of the craft segment has been cited as strongly supportive of resource partitioning theory [

10], building on beer’s more general status as prototypical, and sometimes even precedent-setting, in the context of organizational and economic forces [

8]. Similarly, the US wine industry is seen as providing additional empirical support for resource partitioning theory as jug wine has been displaced by location-specific farm winery products [

11]. By contrast, the reverse appears to be the case for UK wine consumption, where aggregate data suggest a shift from niche, high-end consumption that was apparent in the 1950s to the mass-market mainstream, displacing beer consumption as the category of choice for UK consumers. In other words, partitioning occurred across the alcohol category, with the brewers’ unique distribution platforms acting as

de facto catalytic convertors and social mediums. Moreover, intra-category, the historic profile suggests replacement of authentic sales from countries, such as France and Germany, the former of which was regarded as a high-end luxury product for only knowledgeable consumers, in favor of New World wines, much of which is shipped in bulk into the UK for local bottling.

While my article is undoubtedly a snapshot of the emergence and evolution of the UK wine industry, it has identified the importance of new product development, catchy marketing initiatives and the significance of the early targeting of the social settings and aspirations that women particularly identified with. It is notable that these features and themes remain relevant in contemporary wine research. More work needs to be done, however, to understand more fully why UK wine consumption, while displaying convergence characteristics that are not dissimilar to those identified in other developed markets, at the micro-level appears to contravene the clear segmentation characteristics of resource partitioning in other developed wine markets, save as to state the obvious that the UK, owing to its climate, does not have the same depth of opportunities for craft farm wine, supported by wine tourism.