Shelf Life and Sensory Evaluation of a Potentially Probiotic Mead Produced by the Mixed Fermentation of Saccharomyces boulardii and Kombucha

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mead Production

2.2. Shelf Life of the Prepared Product

2.2.1. Physicochemical Analyses

2.2.2. Microbiological Analyses

2.3. Sensory Evaluation of the Prepared Product

2.3.1. Acceptance and Purchase Intention Test

2.3.2. Check-All-That-Apply (CATA) Test

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

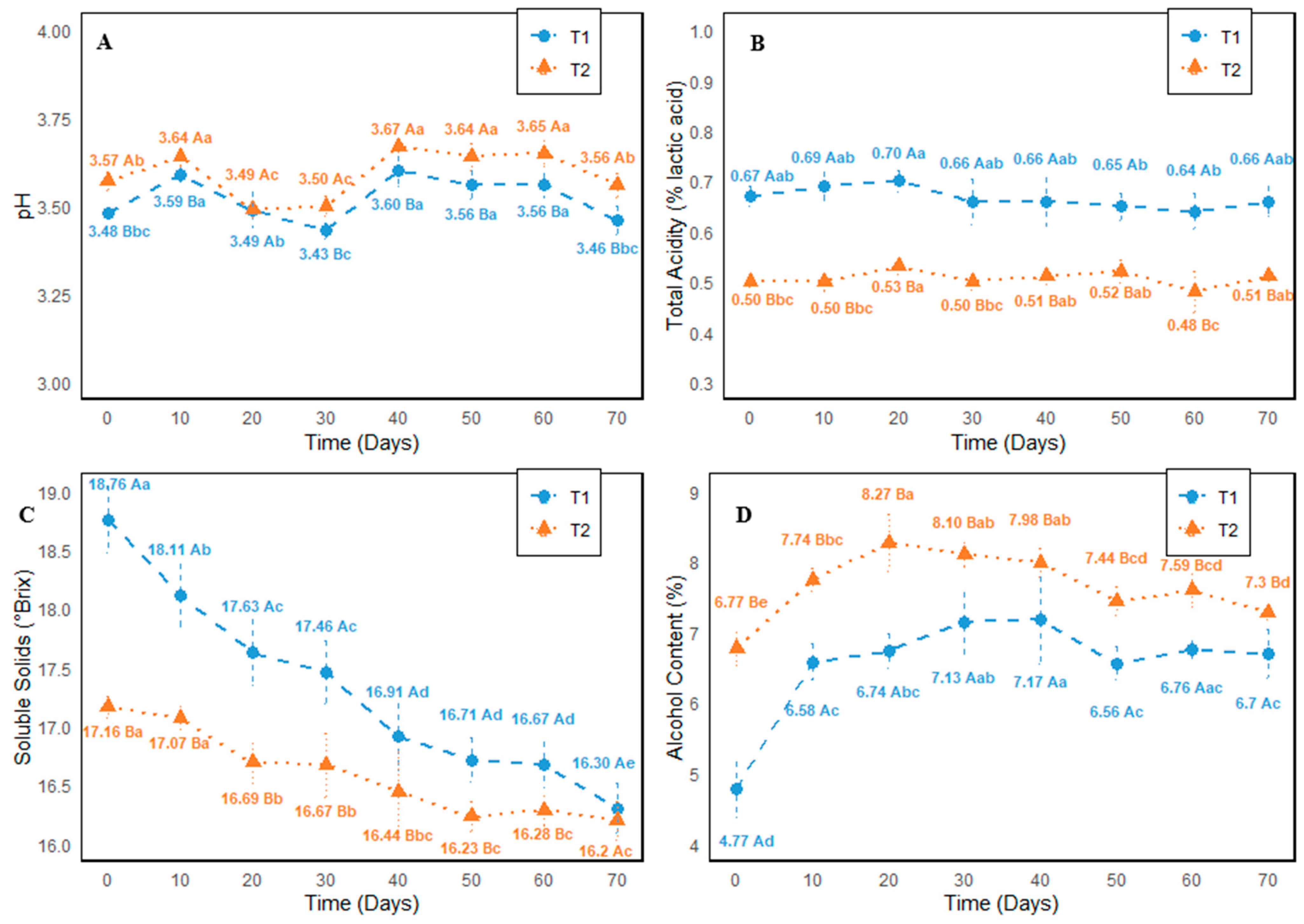

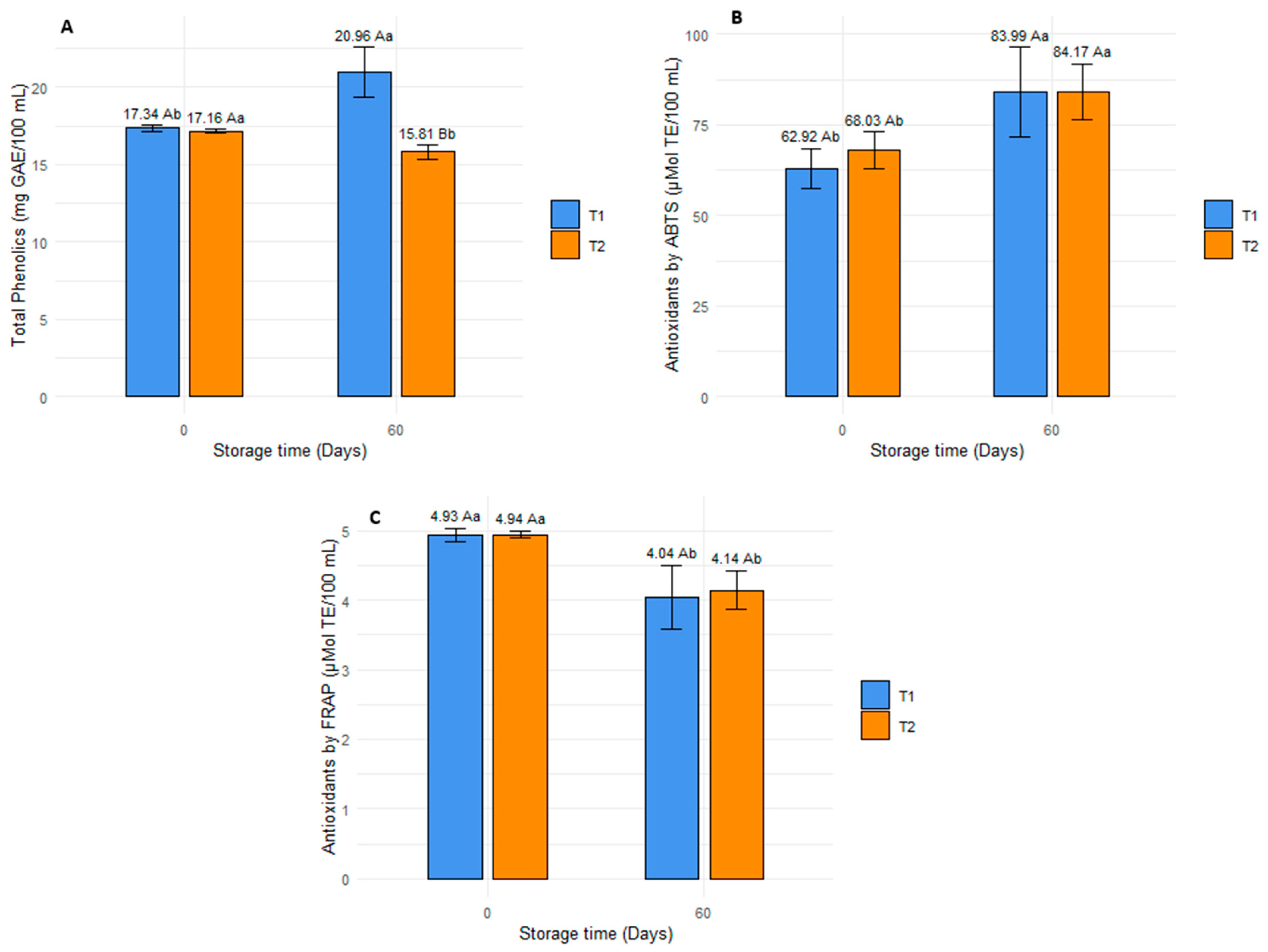

3.1. Shelf Life of Mead

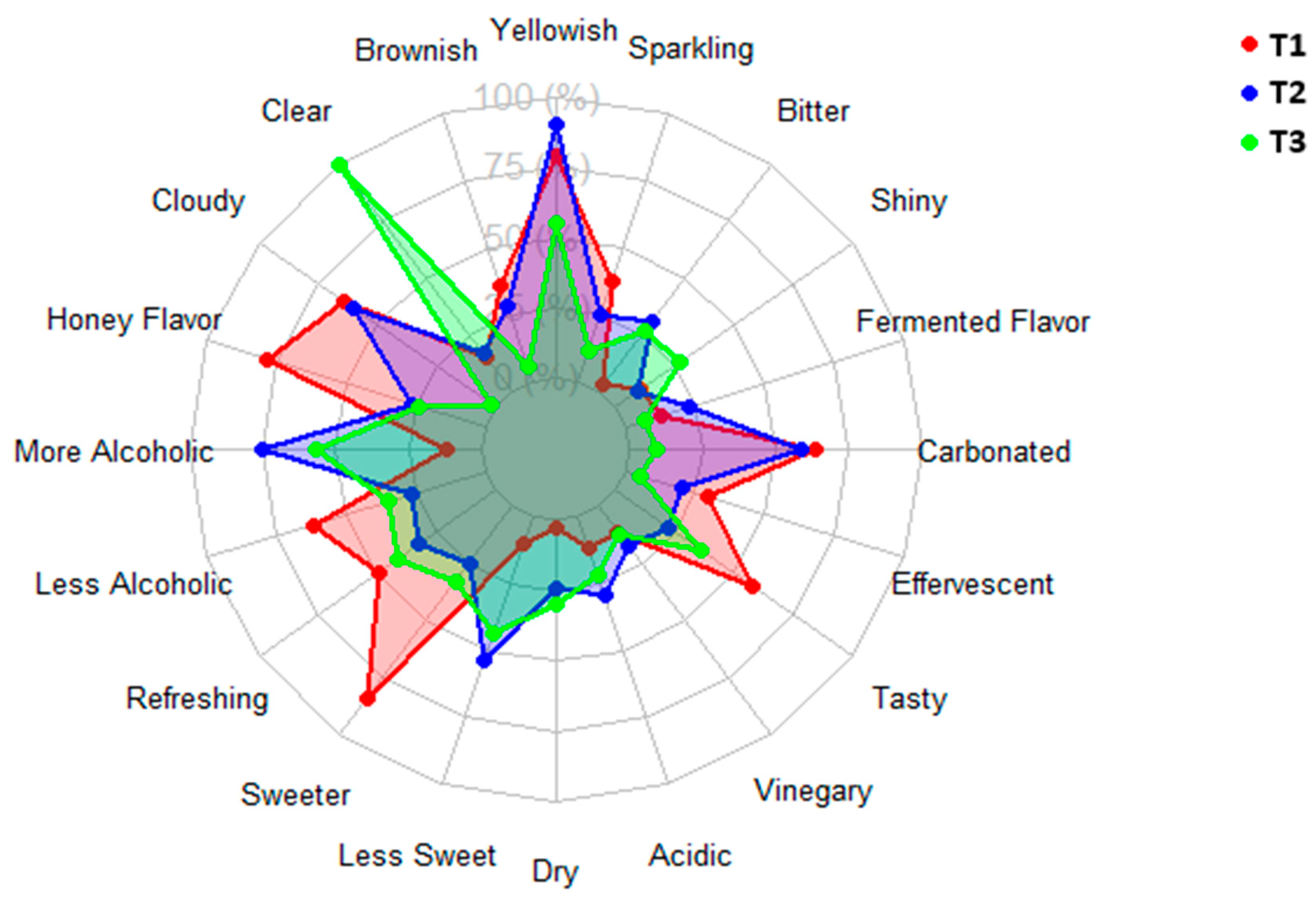

3.2. Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Souza, H.F.; Bogáz, L.T.; Monteiro, G.F.; Freire, E.N.S.; Pereira, K.N.; de Carvalho, M.V.; da Silva Rocha, R.; da Cruz, A.G.; Brandi, I.V.; Kamimura, E.S. Water Kefir in Co-Fermentation with Saccharomyces boulardii for the Development of a New Probiotic Mead. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 3299–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, H.F.; Freire, E.N.S.; Monteiro, G.F.; Bogáz, L.T.; Teixeira, R.D.; Junior, F.V.S.; Teixeira, F.D.; dos Santos, J.V.; de Carvalho, M.V.; da Silva Rocha, R.; et al. Development of Potentially Probiotic Mead from Co-Fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii and Kombucha Microorganisms. Fermentation 2024, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento Pereira, K.; de Souza, H.F.; de Oliveira, A.C.D.; Deziderio, M.A.; Di Próspero Gonçalves, V.D.; de Carvalho, M.V.; Kamimura, E.S. Production of “Melomel” from Cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum) Using the Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii. Fermentation 2025, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starowicz, M.; Granvogl, M. Trends in Food Science & Technology an Overview of Mead Production and the Physicochemical, Toxicological, and Sensory Characteristics of Mead with a Special Emphasis on Flavor. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, H.F.; Bessa, M.S.; Gonçalves, V.D.D.P.; dos Santos, J.V.; Pinheiro, C.; das Chagas, E.G.L.; de Carvalho, M.V.; Brandi, I.V.; Kamimura, E.S. Growing Conditions of Saccharomyces boulardii for the Development of Potentially Probiotic Mead: Fermentation Kinetics, Viable Cell Counts and Bioactive Compounds. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2023, 30, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira de Paula, B.; de Souza Lago, H.; Firmino, L.; Fernandes Lemos Júnior, W.J.; Ferreira Dutra Corrêa, M.; Fioravante Guerra, A.; Signori Pereira, K.; Zarur Coelho, M.A. Technological Features of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii for Potential Probiotic Wheat Beer Development. LWT 2021, 135, 110233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manshin, D.; Meledinaa, T.V.; Britvina, T.; Davydenko, S.G.; Shelekhova, N.V.; Andreev, V.; Andreeva, A. Comparison of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii and Top-Fermenting Brewing Yeast Strains during the Fermentation of Model Nutrient Media and Beer Wort. Agron. Res. 2022, 20, 625–636. [Google Scholar]

- Mulero-Cerezo, J.; Tuñón-Molina, A.; Cano-Vicent, A.; Pérez-Colomer, L.; Martí, M.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Alcoholic and Non-Alcoholic Rosé Wines Made with Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii Probiotic Yeast. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.B.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Valiente, S.; Castro, R.; Lasanta, C. Development and Characterization of Probiotic Beers with Saccharomyces boulardii as an Alternative to Conventional Brewer’s Yeast. Foods 2023, 12, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira Terhaag, M.; Sakai, O.A.; Ruiz, F.; Garcia, S.; Bertusso, F.R.; Prudêncio, S.H. The Probiotication of a Lychee Beverage with Saccharomyces boulardii: An Alternative to Dairy-Based Probiotic Products. Foods 2025, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, H.F.; Monteiro, G.F.; Di Próspero Gonçalves, V.D.; dos Santos, J.V.; de Oliveira, A.C.D.; Pereira, K.N.; Carosia, M.F.; de Carvalho, M.V.; Brandi, I.V.; Kamimura, E.S. Evaluation of Sensory Acceptance, Purchase Intention and Color Parameters of Potentially Probiotic Mead with Saccharomyces boulardii. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento Pereira, K.; Fernandes de Souza, H.; Dias de Oliveira, A.C.; Aparecida Deziderio, M.; Vieira de Carvalho, M.; Rocha, R.S.; Cruz, A.G.; Fernandes de Oliveira, C.A.; Setsuko Kamimura, E. Technological Aspects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii Applications in Fermented Alcoholic Beverages. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2025, 17, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in Adult Patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2202–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulero-Cerezo, J.; Briz-Redón, Á.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. Boulardii: Valuable Probiotic Starter for Craft Beer Production. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; The Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Everette, J.D.; Bryant, Q.M.; Green, A.M.; Bryant, Q.M.; Green, A.M.; Abbey, Y.A.; Wangila, G.W.; Walker, R.B. Thorough Study of Reactivity of Various Compound Classes toward the Folin-Ciocalteou Reagent. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8139–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, K.; Cantu, A.; Heymann, H. Characterizing the Chemical and Sensory Profiles of Traditional American Meads. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, M.; Stright, A.; Baxter, L.; Moss, R.; McSweeney, M.B. An Analysis of Consumer Perception, Emotional Responses, and Beliefs about Mead. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 7426–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Beaufort, S.; Bouajila, J.; Souchard, J.P.; Taillandier, P. Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.; Zhang, X.-X.; Mutukumira, A.N. Kombucha: Production and Microbiological Research. Foods 2022, 11, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.K.A.; Wang, B.; Lima, E.M.F.; Shebeko, S.K.; Ermakov, A.M.; Khramova, V.N.; Ivanova, I.V.; Rocha, R.d.S.; Vaz-Velho, M.; Mutukumira, A.N.; et al. Kombucha: An Old Tradition into a New Concept of a Beneficial, Health-Promoting Beverage. Foods 2025, 14, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capece, A.; Pietrafesa, R.; Siesto, G.; Romaniello, R.; Condelli, N.; Romano, P. Indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains as Starter Cultures for Industrial Wine Production. Food Microbiol. 2018, 70, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zendeboodi, F.; Khorshidian, N.; Mortazavian, A.M.; da Cruz, A.G. Probiotic: Conceptualization from a New Approach. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 32, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazo-Vélez, M.A.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O.; Rosales-Medina, M.F.; Tinoco-Alvear, M.; Briones-García, M. Application of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii in Food Processing: A Review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawa-Rygielska, J.; Adamenko, K.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Szatkowska, K. Fruit and Herbal Meads—Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties. Food Chem. 2019, 283, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peepall, C.; Nickens, D.G.; Vinciguerra, J.; Bochman, M.L. An Organoleptic Survey of Meads Made with Lactic Acid-Producing Yeasts. Food Microbiol. 2019, 82, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, F.; Yan, X.; Li, B.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Fermentation of Mead Using Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Lactobacillus paracasei: Strain Growth, Aroma Components and Antioxidant Capacity. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitenbach, A.; Lorenzi, A.; Ghesti, G.; Santos, P.; Rodrigues, I.; Barbosa, A.; Sant’Ana, R.; Fritzen-Freire, C.; Nowruzi, B.; Burin, V. Advances in Mead Aroma Research: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Review and Insights into Key Factors and Trends. Fermentation 2025, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.E.; Barker, D.; Deed, R.C.; Pilkington, L.I. Mead Production and Quality: A Review of Chemical and Sensory Mead Quality Evaluation with a Focus on Analytical Methods. Food Res. Int. 2025, 202, 115655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Miles, M.P. With the Best of Intentions: A Large Sample Test of the Intention-behaviour Gap in Pro-environmental Consumer Behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalhosa, E.; Gomes, T.; Pereira, A.P.; Dias, T.; Estevinho, L.M. Mead Production. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, A.; Pascoal, A.; Choupina, A.; Carvalho, C.; Feás, X.; Estevinho, L. Developments in the Fermentation Process and Quality Improvement Strategies for Mead Production. Molecules 2014, 19, 12577–12590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attributes | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall impression | 7.75 ± 1.30 a | 6.64 ± 1.63 b | 6.89 ± 1.79 b |

| Color | 7.30 ± 1.71 a | 7.17 ± 1.63 a | 6.89 ± 1.74 a |

| Aroma | 7.19 ± 1.52 a | 6.89 ± 1.61 a | 7.31 ± 1.53 a |

| Flavor | 7.84 ± 1.46 a | 6.23 ± 1.96 b | 6.68 ± 1.94 b |

| Alcohol content | 7.56 ± 1.41 a | 6.56 ± 1.77 b | 6.64 ± 1.90 b |

| Purchase intention | 4.98 ± 1.30 a | 4.10 ± 1.54 b | 4.00 ± 1.72 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teixeira, R.D.; de Souza, H.F.; Junior, F.V.S.; Teixeira, F.D.; Pereira, K.N.; de Oliveira, A.C.D.; da Cruz, A.G.; Brandi, I.V.; Ghantous, G.F.; Kamimura, E.S. Shelf Life and Sensory Evaluation of a Potentially Probiotic Mead Produced by the Mixed Fermentation of Saccharomyces boulardii and Kombucha. Beverages 2025, 11, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060166

Teixeira RD, de Souza HF, Junior FVS, Teixeira FD, Pereira KN, de Oliveira ACD, da Cruz AG, Brandi IV, Ghantous GF, Kamimura ES. Shelf Life and Sensory Evaluation of a Potentially Probiotic Mead Produced by the Mixed Fermentation of Saccharomyces boulardii and Kombucha. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060166

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeixeira, Ricardo Donizete, Handray Fernandes de Souza, Fabiano Vaquero Silva Junior, Felipe Donizete Teixeira, Karina Nascimento Pereira, Amanda Cristina Dias de Oliveira, Adriano Gomes da Cruz, Igor Viana Brandi, Giovana Fumes Ghantous, and Eliana Setsuko Kamimura. 2025. "Shelf Life and Sensory Evaluation of a Potentially Probiotic Mead Produced by the Mixed Fermentation of Saccharomyces boulardii and Kombucha" Beverages 11, no. 6: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060166

APA StyleTeixeira, R. D., de Souza, H. F., Junior, F. V. S., Teixeira, F. D., Pereira, K. N., de Oliveira, A. C. D., da Cruz, A. G., Brandi, I. V., Ghantous, G. F., & Kamimura, E. S. (2025). Shelf Life and Sensory Evaluation of a Potentially Probiotic Mead Produced by the Mixed Fermentation of Saccharomyces boulardii and Kombucha. Beverages, 11(6), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060166