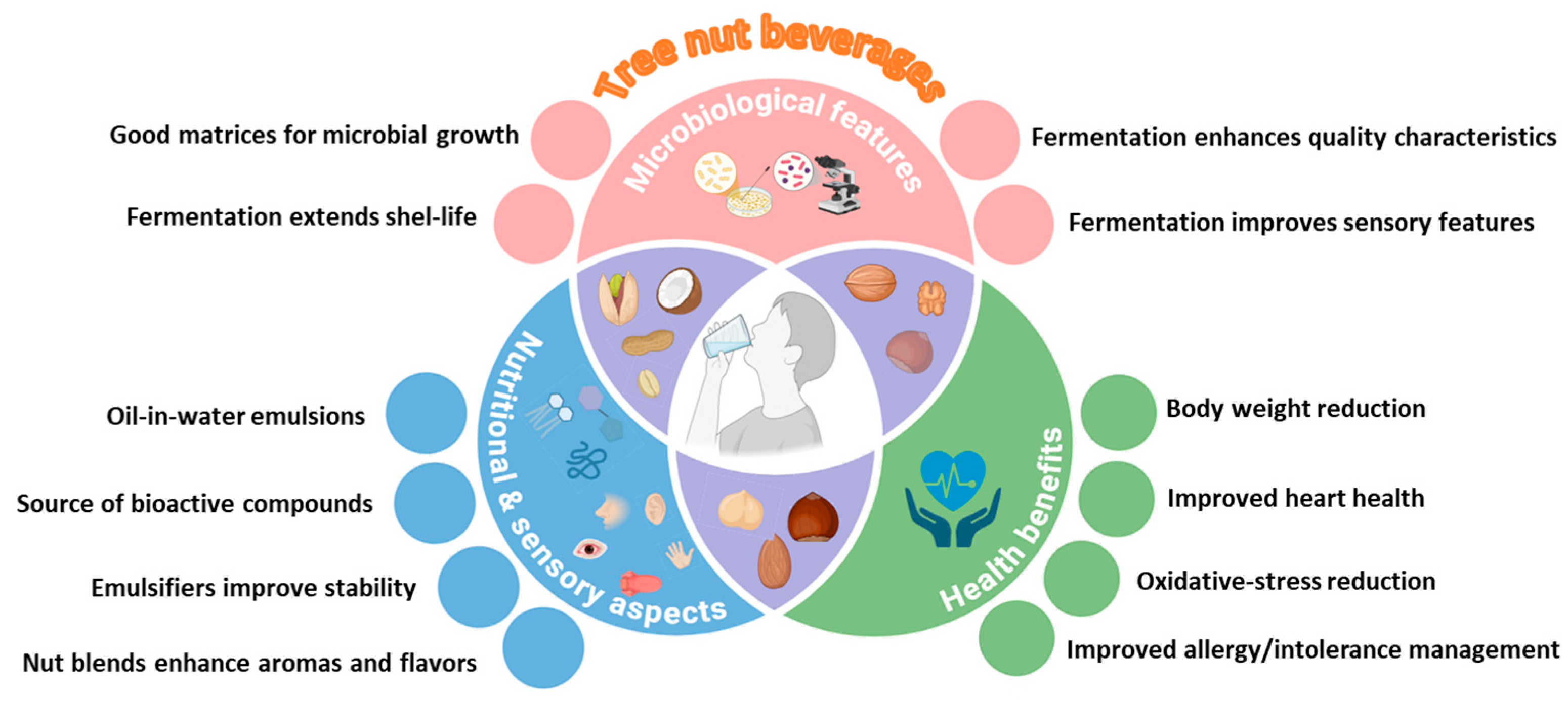

An Overview of the Microbiological, Nutritional, Sensory and Potential Health Aspects of Tree Nut-Based Beverages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Microbiological Aspects

3. Nutritional Characteristics

3.1. Energy Content

3.2. Lipids and Fatty Acid Composition

3.3. Protein Content

3.4. Carbohydrates, Fiber and Sugar Composition

3.5. Mineral and Vitamin Content

3.6. Other Nutritional Aspects of Nut Beverages

4. Sensory Aspects of Nut-Based Beverages

5. Potential Health Benefits of Nut Plant-Based Beverages

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BI | bioaccessibility |

| CE | catechin equivalent |

| CLA | conjugated linoleic acid |

| CLNA | conjugated linolenic acid |

| d.w. | Dry weight |

| EPS | Exopolysaccharides |

| FOS | Fructooligosaccharides |

| f.w. | Fresh weight |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalent |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated Fatty Acids |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| TFC | total flavonoid content |

| TPC | total phenolic content |

References

- Rachtan-Janicka, J.; Gajewska, D.; Szajewska, H.; Włodarek, D.; Weker, H.; Wolnicka, K.; Wiśniewska, K.; Socha, P.; Hamulka, J. The role of plant-based beverages in nutrition: An expert opinion. Nutrients 2025, 30, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingali, P.; Boiteau, J.; Choudhry, A.; Hall, A. Making meat and milk from plants: A review of plant-based food for human and planetary health. World Dev. 2023, 170, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranadheera, C.S.; Vidanarachchi, J.K.; Rocha, R.S.; Cruz, A.G.; Ajlouni, S. Probiotic delivery through fermentation: Dairy vs. non-dairy beverages. Fermentation 2017, 3, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalupa-Krebzdak, S.; Long, C.J.; Bohrer, B.M. Nutrient density and nutritional value of milk and plant-based milk alternatives. Int. Dairy J. 2018, 87, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. Plant-Based Beverages Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Type (Coconut, Soy, Almond), by Product (Plain, Flavored), by Region (APAC, North America, EU, MEA), and Segment Forecasts, 2022–2030; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo, T.; Osimani, A.; Marulo, S.; Cardinali, F.; Mamone, G.; Puppo, M.C.; Garzón, A.G.; Drago, S.R.; Laurino, C.; Reale, A. Insight into the role of lactic acid bacteria in the development of a novel fermented pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) beverage. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Rojas, W.V.; Martín, D.; Fornari, T.; Cano, P. Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) beverage processed by high-pressure homogenization: Changes in main components and antioxidant capacity during cold storage. Molecules 2023, 28, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, A.; Puppo, M.C.; Boscaino, F.; Garzón, A.G.; Drago, S.R.; Marulo, S.; Di Renzo, T. Development and evaluation of a fermented pistachio-based beverage obtained by colloidal mill. Foods 2024, 13, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Yeasmen, N.; Dubé, L.; Orsat, V. A review on current scenario and key challenges of plant-based functional beverages. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Teodocio, J.D.; Gallardo-Velázquez, T.; Osorio-Revilla, G.; Castañeda-Pérez, E.; Velázquez-Contreras, C.; Cornejo-Mazón, M.; Hernández-Martínez, D.M. Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia) nut-based beverage: Physicochemical stability and nutritional and antioxidant properties. Beverages 2024, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha Esperança, V.J.; Corrêa de Souza Coelho, C.; Tonon, R.; Torrezan, R.; Freitas-Silva, O. A review on plant-based tree nuts beverages: Technological, sensory, nutritional, health and microbiological aspects. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 2396–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro de Oliveira, B.; Buranelo Egea, M.; Franca Lemes, S.A.; Hernandes, T.; Pereira Takeuchi, K. Beverage of brazil nut and bocaiuva almond enriched with minerals: Technological quality and nutritional effect in male wistar rats. Foods 2024, 13, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redan, B.W.; Zuklic, J.; Cai, J.; Warren, J.; Carter, C.; Wan, J.; Sandhu, A.K.; Black, D.G.; Jackson, L.S. Effect of pilot-scale high-temperature short-time processing on the retention of key micronutrients in a fortified almond-based beverage: Implications for fortification of plant-based milk alternatives. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1468828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Mendes Coutinho, G.; Chaves Ribeiro, A.E.; Carrijo Prado, P.P.M.; Resende Oliveira, E.; Careli-Gondim, I.; Ribeiro Oliveira, A.; Soares Soares Júnior, M.; Caliari, M.; de Barros Vilas Boas, V. New plant-based fermented beverage made of baru nut enriched with probiotics and green banana: Composition, physicochemical and sensory properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 2607–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor, M.F.; Siddique, R.; Hussain, A.; Ahmad, N.; Rehman, A.; Siddeeg, A.; Alfarga, A.; Alshammari, G.M.; Yahya, M.A. Thermosonication effect on bioactive compounds, enzymes activity, particle size, microbial load, and sensory properties of almond (Prunus dulcis) milk. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 78, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Varela, R.; Hansen, A.H.; Svendsen, B.A.; Moghadam, E.G.; Bas, A.; Kračun, S.K.; Harlé, O.; Poulsen, V.K. Harnessing fermentation by Bacillus and lactic acid bacteria for enhanced texture, flavor, and nutritional value in plant-based matrices. Fermentation 2024, 10, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, A.G.; Puppo, M.C.; Di Renzo, T.; Drago, S.R.; Reale, A. Mineral bioaccessibility of pistachio-based beverages: The effect of lactic acid bacteria fermentation. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2025, 80, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL Zahrani, A.J.; Shori, A.B. Viability of probiotics and antioxidant activity of soy and almond milk fermented with selected strains of probiotic Lactobacillus spp. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 176, 114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Rcoha, C.; Magnani, M.; Jensen Klososki, S.; Marcolino, V.A.; dos Santos Lima, M.; Queiroz de Freitas, M.; Feihrmann, A.C.; Barao, C.E.; Colombo Pimentel, T. High-intensity ultrasound influences the probiotic fermentation of Baru almond beverages and impacts the bioaccessibility of phenolics and fatty acids, sensory properties, and in vitro biological activity. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydar, E.F.; Tutuncu, S.; Ozcelik, B. Plant-based milk substitutes: Bioactive compounds, conventional and novel processes, bioavailability studies, and health effects. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 70, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferragut, V.; Valencia-Flores, D.C.; Pérez-González, M.; Gallardo, J.; Hernández-Herrero, M. Quality characteristics and shelf-life of Ultra-High Pressure Homogenized (UHPH) almond beverage. Foods 2015, 4, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Flores, D.C.; Hern’andez-Herrero, M.; Guamis, B.; Ferragut, V. Comparing the effects of Ultra-High-Pressure Homogenization and conventional thermal treatments on the microbiological, physical, and chemical quality of almond beverages. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez-Rojas, W.V.; Parralejo-Sanz, S.; Martin, D.; Fornari, T.; Cano, M.P. Validation of high-pressure homogenization process to pasteurize brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) beverages: Sensorial and quality characteristics during cold storage. Beverages 2023, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yu, A.; Kong, X.; Hua, Y. Stable mixed beverage is produced from walnut milk and raw soymilk by homogenization with subsequent heating. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2014, 20, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.R.; Bruno, L.M.; Wurlitzer, N.J.; de Sousa, P.H.M.; de Mesquita Holanda, S.A. Cashew nut-based beverage: Development, characteristics and stability during refrigerated storage. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraloni, C.; Albanese, L.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Meneguzzo, F.; Tagliavento, L.; Zabini, F. New route to the production of almond beverages using hydrodynamic cavitation. Foods 2023, 12, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano Zavala, J.L.; Hernández-Martínez, D.M.; Osorio-Revilla, G. Elaboración de una bebida de nuez de macadamia. Investig. Desarro. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2023, 8, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, L.C.; Parmanhane, R.T.; Cruz, A.G.; Barbosa, M.I.M.J. Physicochemical stability and sensory acceptance of a carbonated cashew beverage with fructooligosaccharide added. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 2986–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakerardekani, A.; Karim, R.; Vaseli, N. The effect of processing variables on the quality and acceptability of pistachio milk. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2012, 37, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulo, S.; De Caro, S.; Nitride, C.; Di Renzo, T.; Di Stasio, L.; Ferranti, P.; Reale, A.; Mamone, G. Bioactive peptides released by lactic acid bacteria fermented pistachio beverages. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalar, İ.; Gul, O.; Gul, L.B.; Yazici, F. Storage stability of low and high heat treated hazelnut beverages. GIDA (J. Food) 2019, 44, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalar, İ.; Gul, O.; Mortas, M.; Gul, L.B.; Saricaoglu, F.T.; Yazici, F. Effect of thermal treatment on microbiological, physicochemical and structural properties of high pressure homogenised hazelnut beverage. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2019, 11, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.J.; Cheng, M.C.; Chen, B.Y.; Wang, C.Y. Effect of high-pressure processing on immunoreactivity, microbial and physicochemical properties of hazelnut milk. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalar, I.; Gul, O.; Saricaoglu, F.T.; Besir, A.; Gul, L.B.; Yazici, F. Influence of thermosonication (TS) process on the quality parameters of high pressure homogenized hazelnut milk from hazelnut oil by-products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, O.; Atalar, I.; Mortas, M.; Saricaoglu, F.T.; Besir, A.; Gul, L.B.; Yazici, F. Potential use of high pressure homogenized hazelnut beverage for a functional yoghurt-like product. An. Acad. Brasil. Cienc. 2022, 94, e20191172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkan, S.; Incekara, K.; Otağ, M.R.; Unal Turhan, E. The influence of hazelnut milk fortification on quality attributes of probiotic yogurt. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omeka, W.K.M.; Yalegama, C.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P. Preparation of shelf stable ready to serve (rts) beverage based on tender coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Ann. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 18, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.W.; Rhee, C. Processing suitability of a rice and pine nut (Pinus koraiensis) beverage. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, N.; Cháfer, M.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Development of a non-dairy probiotic fermented product based on almond milk and inulin. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2014, 21, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.M.; Lima, J.R.; Wurlitzer, N.J.; Rodrigues, T.C. Non-dairy cashew nut milk as a matrix to deliver probiotic bacteria. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 40, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, T.L.T.L.; Shinohara, N.K.S.; Marques, M.F.F.; de Lima, G.S.; Andrade, S.A.C. Drink with probiotic potential based on water-soluble extract from cashew nuts. Cienc. Rural 2022, 52, e20210218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhi, T.; Li, S.; Xia, J.; Tian, Y.; Ma, A.; Jia, Y. Untargeted metabolomics revealed the product formation rules of two fermented walnut milk. Food Agric. Immunol. 2023, 34, 2236807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Pu, X.; Sun, J.; Shi, X.; Cheng, W.; Wang, B. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum on the functional characteristics and flavor profile of fermented walnut milk. LWT 2022, 160, 113254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saori, C.; Mauro, I.; Garcia, S. Coconut milk beverage fermented by Lactobacillus reuteri: Optimization process and stability during refrigerated storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarno, M.; Derewiaka, D.; Dytrych, M.; Stawińska, E.; Zaręba, D. Effects of fat content on selected qualitative parameters of a fermented coconut “milk” beverage. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 59, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bernat, N.; Chàfera, M.; Chiralt, A.; Gonzàlez-Martìnez, C. Probiotic fermented almond/milk as an alternative to cow-milk yoghurt. Int. J. Food Stud. 2015, 4, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, N.; Cháfer, M.; Chiralt, A.; Laparra, J.M.; González-Martínez, C. Almond milk fermented with different potentially probiotic bacteria improves iron uptake by intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Int. J. Food Stud. 2015, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muncey, L.; Hekmat, S. Development of probiotic almond beverage using Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GR-1 fortified with short-chain and long-chain inulin fibre. Fermentation 2021, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, G.; Paulauskienė, A.; Baltušnikienė, A.; Kłębukowska, L.; Czaplicki, S.; Konopka, I. Changes in selected quality indices in microbially fermented commercial almond and oat drinks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, G.E.; Keser, A.; Özer, H.B. Determination of nutritional value, antioxidant activities, microbiological and sensory properties of almond, soy and oat based fermented beverages. Int. J. Food Eng. 2025, 21, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha Júnior, P.C.; de Sá de Oliveira, L.; de Paiva Gouvêa, L.; de Alcantara, M.; Rosenthal, A.; da Rocha Ferreira, E.H. Symbiotic drink based on Brazil nuts (Bertholletia excelsa H.B.K): Production, characterization, probiotic viability and sensory acceptance. Cienc. Rural 2021, 51, e20200361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad, S.A.; Lamas, D. Enrichment of a vegetable drink based on Macadamia Nut (Macadamia tetraphylla) with omega-3 and probiotics. Rep. Cient. FACEN 2021, 12, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assamoi, A.A.; Atobla, K.; Ouattara, D.H.; Koné, R.T. Potential probiotic tiger nut-cashew nut-milk production by fermentation with two lactic bacteria isolated from ivorian staple foods. Agric. Sci. 2023, 14, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assamoi, A.A.; Koua, A.; Djeneba, O.H.; D’Avila, G.T.R. Primary characterization of a novel soymilk-cashew fermented with an improving of its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory contents. Food Nutr. Sci. 2023, 14, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo-Tayo, B.C.; Ogundele, B.R.; Ajani, O.A.; Olaniyi, O.A. Characterization of lactic acid bacterium exopolysaccharide, biological, and nutritional evaluation of probiotic formulated fermented coconut beverage. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 2024, 8923217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loginovska, K.; Valchkov, A.; Doneva, M.; Metodieva, P.; Dyankova, S.; Miteva, D.; Nacheva, I. Technology for obtaining of fermented products from walnut milk. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 29, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Guo, W.; Huang, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, B.; Zhao, J.; Cui, S.; Zhang, H. Production of conjugated fatty acids in probiotic-fermented walnut milk via addition of lipase. LWT 2022, 172, 114249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, N.; Cháfer, M.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Hazelnut milk fermentation using probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and inulin. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 2553–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermiş, E.; Güneş, R.; Zent, İ.; Çağlar, M.Y.; Yılmaz, M.T. Characterization of hazelnut milk fermented by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. GIDA J. Food 2018, 43, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bravo, P.; Noguera-Artiaga, L.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Sendra, E. Fermented beverage obtained from hydroSOStainable pistachios. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 3601–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.J.; Kwon, H.C.; Shin, D.M.; Choi, Y.J.; Han, S.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Han, S.G. Apoptosis-inducing effects of short-chain fatty acids-rich fermented pistachio milk in human colon carcinoma cells. Foods 2023, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, T.; Garzòn, A.G.; Sciammaro, L.P.; Puppo, M.C.; Drago, S.R.; Reale, A. Influence of fermentation and milling processes on the nutritional and bioactive properties of pistachio-based beverages. Fermentation 2025, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryani, D.; Pegua, K.; Aryaa, S.S. Review of plant-based milk analogue: Its preparation, nutritional, physicochemical, and organoleptic properties. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Succi, M.; Sorrentino, E.; Di Renzo, T.; Tremonte, P.; Reale, A.; Tipaldi, L.; Pannella, G.; Russo, A.; Coppola, R. Lactic acid bacteria in pharmaceutical formulations: Presence and viability of “healthy microorganisms”. J. Pharm. Nutr. Sci. 2014, 4, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraliakbari, H.; Shahidi, F. Lipid class compositions, tocopherols and sterols of tree nut oils extracted with different solvents. J. Food Lipids 2008, 15, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayarajan, C.T.; Mohan, K.; Nisha, P. Tree nuts: Treasure mine for prebiotic and probiotic dairy free vegan products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipan, L.; Rusu, B.; Simon, E.L.; Sendra, E.; Hernández, F.; Vodnar, D.C.; Corell, M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A. Chemical and sensorial characterization of spray dried hydroSOStainable almond milk. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz-Ahrens, K.E.; Ahrens, F.; Barth, C.A. Nutritional and health attributes of milk and milk imitations. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romulo, A. Food processing technologies aspects on plant-based milk manufacturing. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1059, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. U.S Department of Agriculture. FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Gocer, E.M.C.; Koptagel, E. Production of milks and kefir beverages from nuts and certain physicochemical analysis. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.A. Almond milk production and study of quality characteristics. J. Acad. 2012, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alozie Yetunde, E.; Udofia, U.S. Nutritional and sensory properties of almond (Prunus amygdalu Var. Dulcis) seed milk. World J. Dairy Food Sci. 2015, 10, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Rojas, W.V.; Martín, D.; Miralles, B.; Recio, I.; Fornari, T.; Cano, M.P. Composition of brazil nut (Bertholletia excels HBK), its beverage and by-products: A healthy food and potential source of ingredients. Foods 2021, 10, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-López, D.A.; Parralejo-Sanz, S.; Lobo, M.G.; Cano, M.P. A healthy brazil nut beverage with Opuntia stricta var. Dillenii green extract: Beverage stability and changes in bioactives and antioxidant activity during cold storage. Foods 2024, 13, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.L.B.; Silva, K.S.; Miranda, B.M.; Cardoso, C.F.; da Silva, F.A.; Freitas, F.F. Development and characterization of a nut-based beverage of Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) and macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia). Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, e02223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Fresán, U. International analysis of the nutritional content and a review of health benefits of non-dairy plant-based beverages. Nutrients 2021, 13, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, M.I.; Sánchez-Morgado, J.R.; García-Parra, J.; Ramírez, R.; Hernández, T.; González-Gómez, D. Comparative study of the nutritional and bioactive compounds content of four walnut (Juglans regia L.) cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 31, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Zheng, J.; Jia, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Fan, X.; Ding, Y. Comparative nutritional and physicochemical analysis of plant-based walnut yogurt and commercially available animal yogurt. LWT 2024, 212, 116959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolarinwa, I.F.; Aruna, T.E.; Adejuyitan, J.A.; Akintayo, O.A.; Lawal, O.K. Development and quality evaluation of soy-walnut milk drinks. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 2033–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Dyakonova, A.; Stepanova, V.; Shtepa, E. Preparation of the core of walnut for use in the composition of soft drinks. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tamimi, J.Z. Effects of almond milk on body measurements and blood pressure. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016, 7, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshonturaev, A.; Sagdullaeva, D.; Salikhanova, D. Study of physical and chemical properties of almond milk. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2023, 8, 1004–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaver, S.; Al-Badri, M.; Mitri, J.; Barbar Askar, A.A.; Mottalib, A.; Hamdy, O. Effect of almond milk versus cow milk on postprandial glycemia, lipidemia, and gastrointestinal hormones in patients with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.R.; Duarte, G.B.S.; Reis, B.Z.; Cozzolino, S.M.F. Brazil nuts: Nutritional composition, health benefits and safety aspects. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, K.M.; McCormick, D.P. A nutritional comparison of cow’s milk and alternative milk products. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarnoj, A.; Nilsson, C. Specific IgE to individual allergen components: Tree nuts and seeds. In Elsevier eBooks Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaikma, H.; Kaleda, A.; Rosend, J.; Rosenvald, S. Market mapping of plant-based milk alternatives by using sensory (RATA) and GC analysis. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, M.; Gallardo-Chacón, J.J.; Valencia-Flores, D.; Ferragut, V. Optimization of a headspace SPME GC–MS methodology for the analysis of processed almond beverages. Food Anal. Methods 2015, 8, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, P.; Sharma, A.; Awasti, N.; Wason, S.; Singh, L.; Sharma, S.; Khattra, A.K. Comparative review of nutri-functional and sensorial properties, health benefits and environmental impact of dairy (bovine milk) and plant-based milk (soy, almond, and oat milk). Food Hum. 2024, 2, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.; Barker, S.; Falkeisen, A.; Gorman, M.; Knowles, S.; McSweeney, M.B. An investigation into consumer perception and attitudes towards plant-based alternatives to milk. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClements, D.J.; Decker, E.A.; Popper, L.K. Biopolymer encapsulation and stabilization of lipid systems and methods for utilization thereof. Food Technol. 2005, 44, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pakzadeh, R.; Goli, S.A.H.; Abdollahi, M.; Varshosaz, J. Formulation optimization and impact of environmental and storage conditions on physicochemical stability of pistachio milk. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 4037–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.J.X.; Hallstrom, J.; de Moura Bell, J.M.N.; Delarue, J. Uncovering the sensory properties of commercial and experimental clean label almond milks. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, D.; Kahveci, D. Production of a protein concentrate from hazelnut meal obtained as a hazelnut oil industry by-product and its application in a functional beverage. Waste Biomass Valor. 2020, 11, 5099–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, M.; Barzegar, M.; Sahari, M.A.; Hosseinmardi, N. Development of a novel sugar-free functional beverage containing pistachio green hull extract. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Llobell, F.; Giacalone, D.; Roigard, C.M.; Jaeger, S.R. Plant-based alternatives vs dairy milk: Consumer segments and their sensory, emotional, cognitive and situational use responses to tasted products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 100, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, C.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Health benefits of walnut polyphenols: An exploration beyond their lipid profile. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3373–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.F.; Zeng, X.; Ahmad, N.; Rehman, Z.A.A.; Aadil, R.M.; Roobab, U.; Siddique, R.; Rahaman, A. Effect of pulsed electric field and thermal treatments on the bioactive compounds, enzymes, microbial, and physical stability of almond milk during storage. J. Food Process Preserv. 2020, 44, e14541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buatong, A.; Meidong, R.; Trongpanich, Y.; Tongpim, S. Production of plant-based fermented beverages possessing functional ingredients antioxidant, γ-aminobutyric acid and antimicrobials using a probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain L42g as an efficient starter culture. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2022, 134, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertdinç, Z.; Aydar, E.F.; Hızır Kadı, I.; Demircan, E.; Çetinkaya, S.K.; Özçelik, B. A new plant-based milk alternative of Pistacia vera geographically indicated in Türkiye: Antioxidant activity, in vitro bio-accessibility, and sensory characteristics. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysu, Ş.; Akıl, F.; Çevik, E.; Kılıç, M.E.; İlyasoğlu, H. Development of homemade hazelnut milk-based beverage. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 20, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, N.; Khodaiyan, F.; Mousavi, S.M. Antioxidant activity of fermented hazelnut milk. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-elmonsif, N.M.; El-Zainy, M.A.; Abd-elhamid, M.M. Comparative study of the possible effect of bovine and some plant-based milk on cola-induced enamel erosion on extracted human mandibular first premolar (scanning electron microscope and x-ray microanalysis evaluation). Future Dent. J. 2017, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw Nut | Technological Treatment | Main Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almond (Prunus amygdalus) | Heat treatment (HT) at 90 °C for 90 s | ↓ bacterial growth and stability, ↑ sedimentation | [21,22] |

| UHT at 142 °C for 6 s | no bacterial growth | [21,22] | |

| UHPH (200 and 300 MPa at 55, 65, and 75 °C) with lecithin | no bacterial growth, ↓ particle size and sedimentation, ↑ colloidal stability and hydroperoxide index | [21,22] | |

| Hydrodynamic Cavitation (HC) | extremely low microbial loads | [26] | |

| Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) | HT at 63 °C for 20 min | ↓ microbial loads, total phenolic content and squalene and γ-tocopherol | [7,23] |

| HPH (50, 100, 150, 180 MPa at 55, 65, and 75 °C) | Inactivation of Escherichia coli and controlled microbial loads, good oxidative stability, no significant lipolysis processes, unaltered levels of essential minerals, proteins, and phytochemicals; stable pH, acidity, and °Brix. ↓ in particle size, ↓ total phenolic content, squalene and γ-tocopherol | [7,23] | |

| Use of nanoadditives (Annatto-nanodispersion) | Good physical stability, no significant phase separation or creaming, significant antioxidant activity, ↑ content in lipids, protein, and essential minerals | [2] | |

| Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia) | Use of Xanthan gum, soy lecithin + HT at 85 °C for 15 min | ↓ particle size, ↑ stability of the emulsion, ↓ saturated fatty acids (SFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), ↑ monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), ↓ antioxidant capacity and texture | [10] |

| Gellan gum and soy + lecithin + HT at 70 °C for 6 min | ↓ particle size, ↑ homogeneity of the mixture and physical stability | [27] | |

| Cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale) | UHT at 140 °C for 4 s | no Salmonella spp. detection, ↓ counts of coliforms, yeasts, molds, and Staphylococcus aureus | [25] |

| Carbonated water + fructooligosaccharide (FOS) + preservatives with or without HT at 90° for 1 min | non-significant changes in pH, acidity, soluble solids (°Brix) and reducing sugars, ↓ vitamin C content, stable fructooligosaccharides (FOS) with no hydrolysis, ↓ coliforms and yeasts/molds, no significant sensory difference. ↓↓ vitamin C with heat treatment | [28] | |

| Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) | Colloidal milling + blending in hot water (80 ± 2 °C) for 30 min. + pH 8.5. HT at 70 °C for 30 s | ↑ protein, fat, dry matter, total soluble solid content | [29] |

| Mixing with hot water (80 °C) + grinding + filtration + HT at 70 °C for 30 min | ↓ below 1 log CFU/mL Enterobacteriaceae, fecal and total coliforms, enterococci, total mesophilic bacteria, yeasts, molds, Pseudomonadaceae and LAB. Production of waste in the filtration phase of the beverage (e.g., fibrous outer skin) | [6] | |

| Colloidal mill (3000 rpm with recirculation for 5/10 min) + HT at 70 °C for 30 min | Physically stable beverage with minimal sedimentation, ↓ microbial counts, no processing waste, richness in essential amino acids and bioactive peptides (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibition, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibition) | [8,30] | |

| Hazelnut (Corylus avellana) | HPH at 100 Mpa + HT at 72 °C for 20 min | No total aerobic bacteria, yeasts and molds, stable pH, ↑ protein solubility, better preservation of bioactive compounds, ↓ oxidation, no changes in hydroperoxide index, ↓ viscosity | [31,32] |

| HPH at 100 Mpa + HT at 105 °C for 1 min | No total aerobic bacteria, yeasts and molds, ↓ pH and protein solubility, lipolysis and proteolysis, ↑ total solid content, hydroperoxide index and viscosity, degradation of heat-sensitive compounds, starch gelatinization | [31,32] | |

| HPP at 200, 400, or 600 MPa for 5–10 min, at an initial temperature of 25 °C | Inhibition of total microorganisms, Escherichia coli, coliforms, and yeasts/molds, ↓ hazelnut allergenicity at 600 MPa; ↓ essential and non-essential amino acids; not affected fatty acid composition; stable pH, °Brix, and total sugar contents; ↑ total phenolics and flavonoids; optimum antioxidant activity | [33] | |

| Heat treatment at 80 °C for 3 min | ↓ essential and non-essential amino acids, unaffected fatty acid composition, ↑ total sugar content, not good antioxidant activity, inhibited microbial growth | [33] | |

| HPH at 100 Mpa + Thermosonication at 40% and 60% amplitudes for 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min; 80% amplitude for 3, 5, 10, and 15 min at 40–75 °C | ↓ particle size, sedimentation, ↑ viscosity and consistency at 40–80% amplitude for 3–5 min, complete inactivation of total aerobic mesophilic bacteria and yeast-mould, ↓ pH, soluble protein content, syneresis and sedimentation, ↑ total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity | [34] | |

| HPH at 100 Mpa + HT at 85 °C for 2 min | Complete inactivation of total aerobic mesophilic bacteria and yeast-mould, ↓ pH, antioxidant capacity and soluble protein content, less desirable effects on colour, bioactive compounds and structural/rheological properties | [34] | |

| Cow milk + hazelnut milk in different proportions + HPH at 100 MPa | more stable pH, ↑ acidity, protein content, peroxide value, ↑ fat content, more fluctuation in pH, ↓ acidity, protein content and peroxide value | [35] | |

| Ingredients for probiotic yogurt fortification (0% to 50% hazelnut milk addition) | ↑ pH at ↑ % hazelnut milk addition, ↑ dry matter, total phenolic content, DPPH radical scavenging activity, protein content, softer, less viscous yogurt with 50% hazelnut milk | [36] | |

| Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) | Pectin addition (0.2%, 0.3%, 0.4%) + SO2 addition (0, 30, 50, 70 ppm) + Homogenization + HT at 100 °C for 5, 10, 15, or 20 min | ↓ sedimentation level, best emulsion stability, absence of yeasts, molds, or bacterial growth, ↓ pH with at 13,000 rpm for 2 min + Pasteurization at 100 °C for 5 min + 0.3% pectin + 30 ppm SO2 | [37] |

| Walnut (Juglans regia) | HT at 120 °C for 10 min | ↑ particle size, larger oil droplet aggregates formed | [24] |

| Homogenization-2-stage 40 MPa | ↑ particle size, large droplets broke down but tended to flocculate | [24] | |

| Homogenization (2-stage) at 40 MPa + HT at 120 °C for 10 min | Further ↑ particle size, more floating layer, less precipitate | [24] | |

| Soy milk addition + Homogenization (2-stage) at 40 MPa +HT 120 °C for 10 min | ↑ dispersion stability, ↓ particle size, ↓ walnut protein aggregation, inhibition of β-sheet formation in walnut proteins, ↑ essential amino acids, acceptable sensory and textural properties | [24] | |

| Pine nut (Pinus pinea L.) | Soaked rice + pine nuts + Pressure Homogenization at 0, 19.6 and 29.4 MPa (x2) + HT 121 °C for 20 min + pH adjusted to 5.5, 6.5, and 7.5 | ↑ homogenization pressure and ↑ viscosity, ↓ particle size and stability, non-homogenization and ↑ pH in pH 5.5 samples; good stability and ↓ sedimentation at 4 °C and pH 6.5; initial phase separation at 25 °C; significant sedimentation and phase separation at 40 °C and at pH 7.5 | [38] |

| Nut Beverage | Microbial Species | Technological Treatment | Storage | Inoculum and Fermentation Conditions | Main Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almond (Prunus amygdalus) | Streptococcus thermophilus CECT 986 and Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730, used alone | HPH at 172 MPa + inulin + HT at 85 °C for 30 min | 28 days at 4 °C | 108 CFU/mL; 37 °C for 24 h for L. reuteri; 42 °C for 24 h for S. thermophilus | physical stability; ↑ in particle size; ↓ sugars; L. reuteri counts >107 CFU/mL; ↓ S. thermophilus counts; mannitol production, ↓ acidity, pH ≈ 4.83; ↑ viscosity | [39] |

| S. thermophilus CECT 986 and L. reuteri ATCC 55730, used alone | HPH at 172 MPa and HT at 85 °C for 30 min | 28 days at 4 °C | 108 CFU/mL; 37–42 °C for 24 h | ↑ physical stability; aggregated proteins; ↓ fat globule size; pH ≈ 4.65; ↑ acidity | [46] | |

| L. rhamnosus CECT 278, L. plantarum 3O9, B. bifidum CECT 870, B. longum CECT 4551, S. thermophilus CECT 986, L. delbrueckii subs. bulgaricus, used alone and in combination | HPH at 172 MPa + HT at 121 °C for 15 min | −22 °C | 108 CFU/mL; 37 °C until 4.4 < pH < 4.6 | ↓ fat globule size and pH; ↑ acidity; positive immunomodulatory effects; ↓ TNF-α and IL-6 production; ↑ iron absorption by intestinal cells; no toxic effects on Caco-2 cells | [47] | |

| L. rhamnosus GR-1 | 0, 2 and 5% short-chain or long-chain inulin addition | 30 days at 4 °C | 109 CFU/mL; 37 °C for 9 h—anaerobiosis | short-chain inulin addition ↑ viable counts ↓ pH long-chain inulin addition ↓ viable counts | [48] | |

| L. delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus 27/23, L. plantarum ATCC 8014, L. plantarum PK 1.1., Candida antarctica CAN 0001, Torula casei TCS 0001, Yarrowia lipolytica YLP 0001, Kluyveromyces marxianus KF 0001, Candida lipolytica CLP 0001, used alone | - | - | 105 CFU/mL for bacteria (30–37 °C for 48 h) and 104 CFU/mL for yeasts (30 °C for 48 h) | ↑ LAB and yeast counts, C. lipolytica showed the lowest growth, ↓↓ pH, ↑↑ viscosity (except C. lipolytica beverage), ↓ major fatty acids, ↑ minor fatty acids, enrichment of the aromatic profile (especially in Y. lipolytica beverage) | [49] | |

| S. thermophilus, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, Lactobacillus acidophilus (NCFM™), Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019™), used alone | HT at 90 °C for 10 min | 21 days at 4 °C | ≥108 UFC/mL; 42 °C ± 1 for 5 h—anaerobiosis | good LAB viability except for B. lactis, ↑ fats, ↓ carbohydrates, ↑ total antioxidant activity, ↑ viscosity, stable pH (4.66–4.76), ↓ acidification | [50] | |

| Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) | Lactobacillus casei | High-speed omogenization + Inulin and pectin addition + HT at 80 ± 1 °C for 20 min | 28 days at 4 °C | 6.5 log CFU/g; 37 °C for 12 h—anaerobiosis (fermentation); 4 ± 1 °C for 24 h (maturation) | ↓↓ dietary fiber, ↓ total carbohydrates, minerals and pH, no yeasts and mould counts, no Salmonella spp. detection, Total and thermotolerant coliforms: within legal limits, good Lactobacillus casei stability during storage | [51] |

| Macadamia (Macadamia tetraphylla) | L. rhamnosus | Omega-3 fatty acids addition | - | - | ↑ MUFA LAB count >106 CFU/mL, good sensorial acceptance | [52] |

| Cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale) | B. animalis BB-12®, L. acidophilus, L. plantarum Lyofast SP-1, used alone | Colloidal mill for 4 min + HT at 140 °C for 4 s | 30 days at 4 °C | 108 CFU/mL | LAB count > 107 CFU/mL, ↓ pH, coliforms, Staphylococcus aureus, yeasts, molds count < safe limits, no Salmonella spp. | [40] |

| Lactobacillus paracasei ATCC 334 | L. paracasei + cashew nut + HT at 72 °C ± 2 °C for 20 min | 4 °C | 107 CFU/mL; 35 °C for 6 h—anaerobiosis | ↑ protein content, ↑ higher sensory acceptability, if ↑ cashew nut amount →↓ LAB amount ↑ sensorial acceptance | [41] | |

| L. plantarum (LAC 1), Pediococcus acidilactici (LAC 2), used alone and in combination | Tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus) milk and cashew nut milk (80:20 ratio) + HT at 82 °C for 10 min | - | 107 CFU/g; room temperature | EPS production, ↓ pH, ↑ titratable acidity, proteins, fats and minerals, flavouring and sensory enhancement, ↑ antioxidant and/or anti-inflammatory activity in LAC 1 sample. LAB count > 106−107 CFU/mL, LAC 2 beverage had the highest overall preference | [53] | |

| Weissella paramesenteroides TC6 and Enterococcus faecalis A4, used alone and in combination | Soy milk + cashew nut milk (80:20 ratio) + HT at 82 °C for 10 min | - | 107 CFU/g; room temperature | ↓ pH, bile salt resistance, ↑ titratable acidity, antioxidant and/or anti-inflammatory activity, EPS production, LAB count > 106−107 CFU/mL, TC6 + A4 milk → sensorial appreciation, TC6 milk → most preferred, A4 milk → least preferred, TC6 + A4 milk → sensory appeal and bioactivity | [54] | |

| Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) | L. reuteri DSM 17938 or LR 92 | Homogenization + HT at 95 °C for 5 min | 30 days at 4 °C | 106 CFU/mL; 34–37 °C for 48 h | ↓ pH and ↓ LAB viability during storage; DSM17938> acidification, reuterin production, more efficient use of fructose and glucose (DSM17938), build-up of fructose and use of sucrose (LR92), degradation of malic acid | [44] |

| S. thermophilus, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, L. acidophilus, B. lactis used in combination | Low/Full fat addition + Homogenization for 20 min + HT at 85 °C for 10 min | 28 days at 6 °C | 45 °C for 5h anaerobiosis | ↓ L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and B. lactis count, ↓ pH, ↑ and ↓ hardness and adhesiveness in Low- and Full-fat samples, respectively. ↑ functional fatty acids and sterols | [45] | |

| Pediococcus acidilactici W3 | HT at 90 °C for 30 min—3% yogurt starter culture, EPS, 1.5% LAB strain | 14 days at 4 °C | 1.5 × 106 CFU/mL; 44 °C for 6 h—anaerobiosis | ↓ probiotic viability after 7 days of storage, ↑ lactic acid, significant antioxidant potential, viscosity, bioactivity and prebiotic potential of EPS produced by LAB strain | [55] | |

| Walnut (Juglans regia) | L. plantarum | Homogenization + 95 °C for 10 min + papain hydrolysis | −80 °C | 108 CFU/mL; 37 °C for 24 h | ↓ pH,↑ LAB count, ↑ fermentation speed, ↑ antioxidant activity, ↑ L. plantarum growth | [42] |

| L. plantarum LP56 | Colloidal mill + 2 homogenization steps (35 and 40 Mpa) + HT at 121 °C for 10 min | 24 h at 4 °C | 109 CFU/mL; 37 °C for 4–16 h | ↓ pH, ↑ TA, ↑ free amino acids and unsaturated fatty acids; ↓ aldehydes, ↑ alcohols, esters, ketones → fruity, milky, roasted notes | [43] | |

| L. plantarum NBIMCC 3447, L. gasseri NBIMCC 2450, used alone | FOS addition (1–4%) + 121 °C for 15 min + Freeze-drying | 30 days at 4 °C | ~106 CFU/mL; 37 °C for 16–18 h pH < 4.5. | ↑ LAB count, 4% FOS ↑ LAB survival after lyophilization, L. plantarum > L. gasseri. resistance to freeze-drying | [56] | |

| Lact. plantarum ZS2058, Lact. casei FZSSZ3-L1, Lact. rhamnosus JSWX-3-L2, Limos. reuteri FXJCJ4-2, B. breve CCFM683, used alone | Colloidal mill + lipase from Aspergillus oryzae addition + HT at 85 °C for 20 min | 24 h at 4 °C | 7 log CFU/mL; enzymatic hydrolysis at 37 °C for 3 h, 37 °C for 20–30 h | ↓ pH, ↑ B. breve count and production of CLA and CLNA, slower growth for Lact. casei and Lim. reuteri, lipase-enhanced fatty acid bioavailability | [57] | |

| Hazelnut (Corylus avellana) | L. rhamnosus GG, S. thermophilus | Inulin + xanthan gum + HT at 90 °C for 10 min | 28 days at 4 °C | ~109 CFU/mL; 37 °C for 3–5 h—anaerobiosis | ↓ pH, ↑ acidity, stable colloidal properties, probiotic survival > 108 CFU/mL, overall good sensory acceptability | [58] |

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus | Ultrasonic homogenization at 100 W, 20 kHz for 10 min | 4 °C for 12 h | ~8–9 log CFU/mL 42 °C for 5 h | ↑ acidity, ↑ fat content, slightly ↓ protein, ↓ pH, low viscosity, better dispersion and stability, ↓ consistency, and overall acceptability | [59] | |

| Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) | 43 different LAB strains | Grinding (Thermomix) + HT at 70 °C for 30 min | 30 days at 4 °C | ~6 log CFU/mL; 30 °C for 24 h | ↓ pH, good acidification, good LAB growth, sensory acceptability confirmed | [6] |

| Starters used: MA400: S. thermophilus + 3 different Lactococcus lactis (subsp. lactis, cremoris, and diacetylactis) MY800: S. thermophilus + 2 L. delbrueckii (subsp. lactis, and bulgaricus) | Grinding (Thermomix) + HT at 70 °C for 30 min | 30 days at 4 °C | 30 °C for 12 h (MA400) and 42 °C for 5 h (MY800) | LAB count > 7 log CFU/g, ↓ pH, ↑ acidity, more complex volatile profile in conventional pistachios fermented with MY800, highest total volatiles in MY800-fermented conventional pistachio beverages: terpenes > aldehydes > alcohols | [60] | |

| S. thermophilus, L. bulgaricus, L.acidophilus, L. gasseri, B. bifidum, used alone or in combination | 4 probiotic combinations: Homogenization at 10,000 rpm for 10 min + 4% inulin + HT at 85 °C for 30 min | 4 °C o/n | 107 CFU/mL; 42 °C until pH 4.6 | ↓ pH, 4% inulin produced ↑acetate, butyrate and lactate →↓ Caco-2 cell viability. B. bifidum + inulin →↑ SCFA production, acetate, and exerted strong anti-cancer effects | [61] | |

| Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides D4 and Companilactobacillus paralimentarius G3, used alone | Colloidal mill for 5 min at room temperature + HT at 70 °C for 30 min | 30 days at 4 °C | ~6 log CFU/mL; 28 °C for 24 h | ↓ pH, ↑ lactic and acetic acid production, ↑↑ LAB count, ↑ free amino group and antioxidant activity, 31 potentially bioactive peptides, ↓ 2S albumin, 7S and 11S globulins, ↓ IgE-binding capacity | [30,62] | |

| Leuc. pseudomesenteroides PD4, Lact. plantarum PT1, Comp. kimchi PU2, Lact. plantarum PV2, Comp. alimentarius PG3, and Lact. paraplantarum PN4, used alone | colloidal mill 3000 rpm for 10 min + HT at 70 °C for 30 min | 30 days at 4 °C | ~6 log CFU/mL; 28 °C for 24 h | ↑ glutamic acid (Glu), arginine (Arg), and serine (Ser), GABA, LAB counts > 108 CFU/mL, terpenoids, acetoin and 2,3-butanedione production, contaminating microbial count < 1 log CFU/mL, ↑ alcohol production in presence of Leuc. pseudomesenteroides PD4 | [8,17] |

| Nut | Product | Energy 1 | Lipids | Proteins | CarboH | Fiber | Ashes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almond (Prunus amygdalu) | Raw almond | 584 | 51.4 | 21.4 | 20.0 | 10.8 | 3.2 | [70] |

| Beverage made with soaked (12 h) almonds, then blended with water 1:5 (almond/water) and filtered | 68 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | - | - | [71] | |

| Beverage made with 4% (w/w) almond in water at 80 °C, milled, filtered and homogenized. Lecithin (0.03% w/w) was added | 26 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | - | 0.2 | [72] | |

| Sweetened beverage made with almonds mixed with water (4 °C—6 h), drained, milled (1:3 nut/water w/v) and strained. Sugar syrup was added and the filtrate was homogenized | 55 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 3.0 | [73] | |

| Beverage made with almond, unsweetened, plain | 15 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | [70] | |

| Brazil nut (Bertholletia excels) | Raw Brazil nut | 669 | 58.5 | 16.0 | 19.6 | - | 3.4 | [74] |

| Beverage made with ground Brazil nuts, homogenized with water at 75 °C, ratio of 7:1 (water/Brazil nut, v/w), filtered and partially defatted | 41.3 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | - | 0.1 | [75] | |

| Beverage made with ground Brazil nuts, homogenized with water at 75 °C, ratio 7:1 (water/raw material, v/w), and filtered | 60.6 | 5.2 | 1.4 | 1.9 | - | 0.3 | [74] | |

| Beverage made with Brazil nut (40%), macadamia nut (10%), and water (50%) | - | - | 7.4 | 4.0 | - | 1.5 | [76] | |

| Cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale) | Raw cashew nut | 533 | 38.9 | 17.4 | 36.3 | 4.1 | 2.6 | [70] |

| Beverage made with soaked (12 h) cashews, then blended with water 1:5 (cashew/water) and filtered | 60 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 3.1 | - | - | [71] | |

| Sweetened beverage made with ground cashew mixed 1:10 with water, 3% sugar, and heat-treated (140 °C—4 s) | 65 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 5.4 | 0.3 | [25] | ||

| Commercial hazelnut beverages | 55 | - | 1.1 | 0.8 | - | - | [77] 2 | |

| Hazelnut (Corylus avellana) | Raw hazelnut | 602 | 53.5 | 13.5 | 26.5 | 8.4 | 2.2 | [70] |

| Beverage made with soaked (12 h) hazelnuts, then blended with water 1:5 (hazelnut/water) and filtered | 74 | 7.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | - | - | [71] | |

| Commercial hazelnut beverages | 70 | - | 1.0 | 7.3 | - | - | [77] 2 | |

| Macadamia nut (Macadamia integrifolia) | Raw macadamia nut | 669 | 64.9 | 7.8 | 24.1 | 7.6 | 1.4 | [70] |

| Beverage made with macadamia nut (40%), Brazil nut (10%), and water (50%) | - | - | 4.8 | 5.7 | - | 0.9 | [76] | |

| Pistachio (Pistacia vera) | Raw pistachio | 598 | 45.0 | 20.5 | 27.7 | 7.0 | 2.8 | [70] |

| Beverage made from roasted or soaked pistachios and hot water 1:5 (pistachio/water) and sugar (5%) | - | 5.0–6.0 | 3.0–4.4 | - | - | - | [29] | |

| Beverage made from soaked pistachios and hot water 1:5 (pistachio/water) and filtered | - | - | 1.6–1.7 | - | - | 0.2–0.3 | [60] | |

| Fermented beverage made with soaked pistachio (25 °C—5 h), ground, filtered, and heat-treated | 50 | 4.6 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 0.3 | [6] | |

| Fermented beverage made with ground pistachios (1:5 pistachio/water) in a colloidal mill (10 min) | 99 | 8.3 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.6 | [8] | |

| Walnut (Juglans regia) | Raw walnut | 690 | 62.1 | 16.1 | 16.0 | - | 1.2 | [78] |

| Soaked walnut (60 °C—2 h) and homogenized 1:8 with water at 60 °C and filtered | - | 66.2 | 2.9 | - | - | - | [79] | |

| Beverage made with boiled walnuts (1 h), blended with water (1:2 w/v) and filtered | 92 | 7.4 | 1.7 | 4.8 | - | 0.2 | [80] | |

| Beverage made with soaked (12 h) walnuts, then blended with water 1:5 (walnut/water) and filtered | 72 | 7.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | - | - | [71] | |

| Beverage made with soaked (10 h) walnuts, then blended with water 1:7 (walnut/water), filtered and mixed with fructose | 73 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 4.7 | - | 0.7 | [81] | |

| Cow’s milk (whole) | 61 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.63 | - | 0.8 | [70] | |

| Nut Beverage | Process | Health Property | Bioactive Compound Content | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almond (Prunus amygdalus) | Fermented with Lactobacillus spp. and stored for 21 days | In vitro antioxidant (DPPH, FRAP and FIC). | TPC (30.7–90.1 μg GAE/mL) | [18] |

| TFC (16.0–27.3 μg/g) | ||||

| Pulsed electric field treatment and stored for 28 days | In vitro antioxidant activity (DPPH and TEAC). | TPC (748.3 μg GAE/g) | [99] | |

| TFC (420.7 μg CE/g) | ||||

| Thermosonication (45 °C for 40 min) | In vitro antioxidant (DPPH, TEAC, hydroxyl radical scavenging). | TPC (766.3 μg GAE/g) | [99] | |

| TFC (429.2 μg GAE/g) | ||||

| Spray-dried almond milk, enriched with probiotic (L. plantarum ATCC 8014) | In vitro antioxidant activity (ABTS, DPPH and FRAP). | TPC (710 μg GAE/kg) | [67] | |

| Microfluidization in a HPH + Fermentation with Lactobacillus spp. + simulated gastrointestinal digestion | Positive immunomodulatory effects on macrophages. | - | [47] | |

| Increase iron uptake by intestinal epithelial cells. | ||||

| Processing with kitchen blender, boiling for 20 min, and straining fermented with L. plantarum L42g | DPPH radical scavenging activities (%) decreased from the initial 43.2% to 29.2% at 12 h fermentation, then sharply increasing to 62% at 24 h. | GABA (~1500 mg/L at 12 h and 2500 mg/L at 24 h fermentation) | [100] | |

| - | Clinical study (30 volunteers) of daily consumption (240 mL) of almond milk for 4 weeks: decreased body weight, body mass index and waist and hip circumference, without effect on. | - | [82] | |

| Baru almond (Dipteryx alata) | High-intensity ultrasound and probiotic fermented (L. casei-01), stored for 28 days | In vitro antidiabetogenic (⍺-amylase and ⍺-glucosidase inhibition). | Gallic acid (2300 μg /L, BI 33%) | [19] |

| In vitro antioxidant (ABTS and DPPH scavenging). | Procyanidin B1 (2960 μg/L, BI 79%) | |||

| Quercetin 3-glucoside (3870 μg/L, BI 71%) | ||||

| Procyanidin A2 (6390 μg/L, BI 64%) | ||||

| Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) | - | In vitro antioxidant (DPPH) | Gallic acid (0.2–2.5 μg/g) | [101] |

| Catechin (19.4–80.2 μg/g) | ||||

| Ferulic acid (0.2–3.9 μg/g) | ||||

| Quercetin (0.9–2.3 μg/g) | ||||

| Fermented with L. pseudomesenteroides D4 and C. paralimentarius G3 | In silico bioactive peptides identified: ACE inhibitor, Renin inhibitor, DPP-IV inhibitor, antioxidant. | Bioactive peptides (494 endogenous peptides identified by LC-MS/MS) | [30] | |

| Fermented with Lactobacillus spp. | Cytotoxicity and apoptotic cell death against colon carcinoma cells (Caco-2), through the microtubule disruption and nuclear damage mediated by caspase-3 (potential for treatment of colon cancer). | - | [61] | |

| Hazelnut (Corylus avellana) | - | In vitro antioxidant activity (DPPH and FRAP). | TPC (51.4 μg/mL) | [102] |

| Fermented with kefir grains | In vitro antioxidant activity (DPPH, reducing power, and ferrous-ion chelating ability). | TPC (917 μg GAE/mL) | [103] | |

| Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) | Nuts were ground, homogenized with water and filtered with stainless mesh | In vitro antioxidant activity (DPPH, TEAc and ORAC). | TPC (795–3140 μg GAE/g d.b.) | [74] |

| High-pressure homogenization treatment and storage for 21 days | In vitro antioxidant activity (ABTS and DPPH). | TPC (69.2 μg GAE/mL) | [7] | |

| Mineral enrichment: 25 mg of calcium plus 0.35 mg of iron | In vivo studies: beverage administration on Wistar rats: decreases in retroperitoneal adipose tissue, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. | TPC (50 μg GAE/g) | [12] | |

| (5% DRIs of minerals) | ||||

| Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia) | Formulated with xanthan gum and soy lecithin | In vitro antioxidant (ABTS and DPPH). | - | [10] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Renzo, T.; Garzón, A.G.; Nazzaro, S.; Marena, P.; Carboni, A.D.; Puppo, M.C.; Drago, S.R.; Reale, A. An Overview of the Microbiological, Nutritional, Sensory and Potential Health Aspects of Tree Nut-Based Beverages. Beverages 2025, 11, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11050144

Di Renzo T, Garzón AG, Nazzaro S, Marena P, Carboni AD, Puppo MC, Drago SR, Reale A. An Overview of the Microbiological, Nutritional, Sensory and Potential Health Aspects of Tree Nut-Based Beverages. Beverages. 2025; 11(5):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11050144

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Renzo, Tiziana, Antonela G. Garzón, Stefania Nazzaro, Pasquale Marena, Angela Daniela Carboni, Maria Cecilia Puppo, Silvina Rosa Drago, and Anna Reale. 2025. "An Overview of the Microbiological, Nutritional, Sensory and Potential Health Aspects of Tree Nut-Based Beverages" Beverages 11, no. 5: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11050144

APA StyleDi Renzo, T., Garzón, A. G., Nazzaro, S., Marena, P., Carboni, A. D., Puppo, M. C., Drago, S. R., & Reale, A. (2025). An Overview of the Microbiological, Nutritional, Sensory and Potential Health Aspects of Tree Nut-Based Beverages. Beverages, 11(5), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11050144