1. Introduction

Approximately 8 million United States (US) high school (HS) students participated in sports in 2013–2014 [

1]. Though research has analyzed consumption of high-calorie drinks by HS students [

2], sports and energy (S/E) drink consumption by HS athletes has largely remained unstudied. The literature lacks data regarding prevalence and patterns of S/E drink consumption and the drinks’ possible side-effects in this specific population.

Sports and energy drinks are distinctly different. Sports drinks aim primarily to replace water and salts lost through perspiration; they contain water, electrolytes, and carbohydrates [

3]. Energy drinks have caffeine as their main active ingredient [

4]. Energy drinks may also contain sugars, artificial sweeteners, vitamins, taurine, ginseng, and

l-carnitine [

4]. Specific ingredients in individual S/E drinks may vary widely.

Some negative effects of S/E drink ingredients have been investigated. There is a strong link between consumption of sweetened drinks and childhood obesity [

5]. Sports drinks can harm teeth [

6]. Energy drinks may have additional psychological effects, such as anxiety and insomnia caused by the high quantities of caffeine [

7]. Teenagers who consume energy drinks are more likely to use alcohol and drugs [

8]. Energy drinks themselves can result in acute cardiovascular issues and possible chronic concerns [

9].

The consumption patterns of S/E drinks by HS athletes, and the drinks’ effects on this group, are not fully known. The objectives of this pilot study were to survey HS athletes about their use of S/E drinks and assess potential side-effects. Our specific aims were to: (1) describe S/E drink consumption prevalence and patterns; (2) assess self-reported side-effects; and (3) determine an association between S/E drink consumption and body mass index (BMI).

2. Methods

An internet-based survey was administered to a convenience sample of 100 athletes from schools participating in the National High School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study (High School RIO™). This national ongoing prospective surveillance study has been described previously [

10,

11]. The authors e-mailed Certified Athletic Trainers (ATs) at participating schools in May 2009 and explained the study objectives and procedures. The ATs were to inform their schools’ athletes about the study and provide an internet link to the survey. Any athlete from a High School RIO™ study school with internet access and English literacy was eligible to participate. The first 100 students completing the survey received a $5 gift certificate; those surveys were used for data analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

The anonymous survey captured self-reported variables including demographics, athletic participation, patterns of consumption, height and weight, and side-effects of S/E drinks. Student athletes were provided a drop down list of specific types of drinks in each category (

i.e., sports and energy) as well as the ability to write in additional answers not included in the drop down options. Similarly, they were provided a drop down list of types of potential side-effects as well as the ability to write in additional answers not included in the drop down options. Consumption frequency was classified into seven categories based on number of days student athletes consumed S/E drinks per month: non-users, rare users (1–2 days per month), occasional users (3–5 days), frequent users (6–9 days), regular users (10–19 days), heavy users (20–29 days), and habitual users (every day). Age- and gender-specific BMI percentiles were calculated using guidelines developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [

12].

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Epi Info (version 6.0; CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to determine strengths of association. The chi-square test and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate statistical significance. CIs not containing 1.0 and p < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results and Discussion

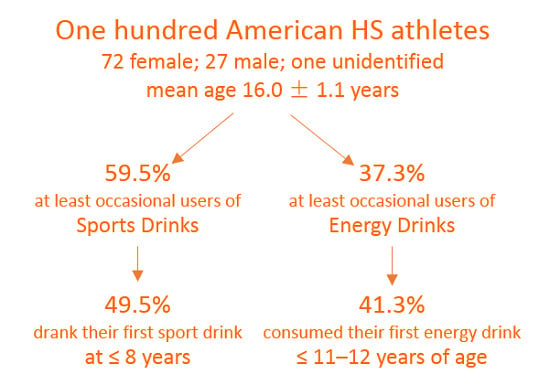

Demographic data are reported in

Table 1. More females (

n = 72) than males (

n = 27) participated. Respondents most commonly participated in track & field, soccer, and basketball.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of High School (HS) Athletes Completing Survey.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of High School (HS) Athletes Completing Survey.

| | Female (n = 72) | Male (n = 27) | Total (n = 100) * |

|---|

| Year in School |

| Freshman | 23.6% | 0.0% | 17.0% |

| Sophomore | 19.4% | 0.0% | 14.0% |

| Junior | 36.1% | 77.8% | 47.0% |

| Senior | 20.8% | 22.2% | 22.0% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Age (years) |

| Minimum | 12 or younger | 16 | 12 or younger |

| Maximum | 18 or older | 18 or older | 18 or older |

| Mean (St. Dev) ** | 16 (1.2) | 17 (0.6) | 16 (1.1) |

| BMI |

| Minimum | 17.2 | 18.2 | 17.2 |

| Maximum | 33.3 | 30.0 | 33.3 |

| Mean (St. Dev) | 22.6 (3.4) | 23.0 (2.6) | 22.7 (3.2) |

| Sports Played † |

| Track & Field | 19.4% | 11.1% | 17.0% |

| Soccer | 12.5% | 25.9% | 17.0% |

| Basketball | 9.7% | 37.0% | 17.0% |

| Field Hockey | 16.7% | 0.0% | 12.0% |

| Lacrosse | 12.5% | 7.4% | 11.0% |

| Football | 2.8% | 29.6% | 10.0% |

The most popular S/E drinks consumed are listed in

Table 2. Sports drinks were more commonly consumed than energy drinks.

Table 2.

Five Most Popular Sports Drinks and Energy Drinks Consumed by HS Athletes Completing the Survey. †

Table 2.

Five Most Popular Sports Drinks and Energy Drinks Consumed by HS Athletes Completing the Survey. †

| | Female (n = 72) | Male (n = 27) | Total (n = 100) * |

|---|

| Sports Drink |

| Gatorade | 98.6% | 100.0% | 99.0% |

| Powerade | 91.5% | 96.3% | 92.9% |

| Muscle Milk | 2.9% | 51.9% | 16.5% |

| Promax | 5.6% | 14.8% | 8.0% |

| Myoplex | 4.2% | 11.1% | 6.1% |

| Energy Drink |

| Red Bull | 62.0% | 85.2% | 68.7% |

| Monster | 50.0% | 70.4% | 56.0% |

| Amp | 46.5% | 66.7% | 52.5% |

| Rockstar | 47.2% | 63.0% | 52.0% |

| Full Throttle | 26.8% | 40.7% | 30.3% |

Consumption frequency was classified into 7 categories based on number of drinks consumed per month. For sports drinks, 13.8% of students were non-users (consumed a sports drink 0 days per month), 26.6% rare users (consumed a sports drink 1 or 2 days per month), 23.4% occasional users (consumed a sports drink 3 to 5 days per month), 13.8% frequent users (consumed a sports drink 6 to 9 days per month), 10.6% regular users (consumed a sports drink 10 to 19 days per month), 7.4% heavy users (consumed a sports drink 20 to 29 days per month), and 4.3% habitual users (consumed a sports drink every day of the month). Energy drink consumption was less common: 30.7% of students were non-users, 32.0% rare users, 20.0% occasional users, 12.0% frequent users, 1.3% regular users, 2.7% heavy users, and 1.3% habitual users. Although there were no significant differences in consumption prevalence between males and females, a higher proportion of males consumed sports drinks more frequently than females.

Of athletes who ever drank a sports drink, 49.5% consumed their first at ≤8 years, 19.2% at 9–10, 16.2% at 11–12, 7.1% at 13–14, and 8.1% at 15–16. Energy drink consumption generally occurred later, with 12.5% consuming their first at ≤8 years, 11.3% at 9–10, 17.5% at 11–12, 27.5% at 13–14, 27.5% at 15–16, and 3.8% at ≥17. Overall, 41.3% consumed their first energy drink ≤11–12 years of age.

Athletes consumed sports drinks before (41.1%), during (59.3%), and after (67.0%) sports; at meals (16.5%); and at “other times” (36.3%) to rehydrate (84.1%), for taste (79.3%), and because of parental purchasing (33.7%). Less than a fifth (18.0%) consumed them to improve athletic performance. Others’ influence also motivated consumption; 11.2% consumed them because teammates did and 10.1% under coaches’ orders. Demonstrating a lack of knowledge regarding sports drinks’ effects, 31.5% consumed them for energy and 16.9% to stay awake.

Athletes consumed energy drinks before (17.2%), during (14.1%), and after (18.5%) sports; at meals (6.2%); and at “other times” (67.7%) to gain energy (61.8%), for taste (60.3%), to stay awake (57.4%), to rehydrate (29.4%), to improve decision making (13.2%), and because teammates did (13.4%). Males in particular drank them to gain energy (80.0%) and improve athletic performance (20.0%).

Self-reported side effects were frequent (

Table 3). Over a quarter of energy drink users reported feeling nervous/jittery after consumption. Increased frequency of consuming either type of drink was not significantly associated with the likelihood of experiencing a side effect.

Table 3.

Self-reported Side-effects of Sports Drinks and Energy Drinks. †

Table 3.

Self-reported Side-effects of Sports Drinks and Energy Drinks. †

| | Female (n = 72) | Male (n = 27) | Total (n = 100) * |

|---|

| Sports Drinks |

| Dizzy, lightheaded | 6.9% | 0.0% | 5.1% |

| Nausea | 11.1% | 0.0% | 8.1% |

| Blurred vision | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Dehydrated | 15.3% | 7.4% | 13.1% |

| Abdominal cramping/diarrhea | 9.7% | 3.7% | 8.1% |

| Nervous/jittery | 12.5% | 3.7% | 10.1% |

| Insomnia | 6.9% | 3.7% | 6.1% |

| Other ** | 2.8% | 0.0% | 2.0% |

| Energy Drinks |

| Dizzy, lightheaded | 13.9% | 14.8% | 14.1% |

| Nausea | 12.5% | 7.4% | 11.1% |

| Blurred vision | 2.8% | 0.0% | 2.0% |

| Dehydrated | 15.3% | 7.4% | 13.1% |

| Abdominal cramping/diarrhea | 5.6% | 3.7% | 5.1% |

| Nervous/jittery | 26.4% | 22.2% | 25.3% |

| Insomnia | 11.1% | 3.7% | 9.1% |

| Other *** | 5.6% | 3.7% | 5.1% |

4. Conclusions

This pilot study surveyed HS athletes from across the United States to gather information about consumption patterns and motivation for consumption of S/E drinks and to explore the side-effects of S/E drinks. S/E drinks were consumed frequently in this population. We also found that of the athletes who had consumed at least one S/E drink, their exposure to the product often came early.

Side-effects were reported frequently with 13.1% of all sports drink users reporting dehydration as a side-effect and 25.3% of all energy drink users reporting being nervous/jittery. The only side-effect that no young athletes reported having after consuming sports drinks was blurred vision. Given that every side-effect, except blurred vision in sports drink consumers, was reported by at least some S/E consumers, our study indicates this is a matter of concern. Although our study sheds initial light on the potential side-effects of S/E drink consumption, given the growing popularity of S/E drinks and the trend toward younger children’s consumption [

7], further research on their short and long-term health effects in young athletes is needed.

Our findings should be interpreted with caution given the study limitations. For example, this pilot study was conducted in a convenience sample of 100 student athletes. This limit, imposed by the small amount of funds available for participant incentives, raises concerns regarding generalizability to the broader student athlete population. Additionally, there was a preponderance of female subjects in this study, yet prior research indicates S/E drinks are typically used more frequently by males [

7]. Football players were underrepresented in our sample as football is the most frequently played HS sport in the U.S. [

1]. Finally, all data were self-reported, opening the possibility of reporting biases. Despite these limitations, this work appears to be one of the first to discuss the age of first consumption of S/E drinks, motivation for consumption, and side effects. While future research should confirm this work, our findings should drive hypotheses for further work in this area.

The young age of first consumption of S/E drinks in this population is concerning as were some of the motivations for consumption. Additionally, it appears negative side effects, such as being nervous/jittery, are common among young athletes consuming energy drinks. Additional research into this area is needed, including larger surveys with increased power. HS athletes should currently be cautioned regarding consumption of S/E drinks until such research better elucidates the effects of these drinks in this population.