Synergistic Triad of Mixed Reality, 3D Printing, and Navigation in Complex Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

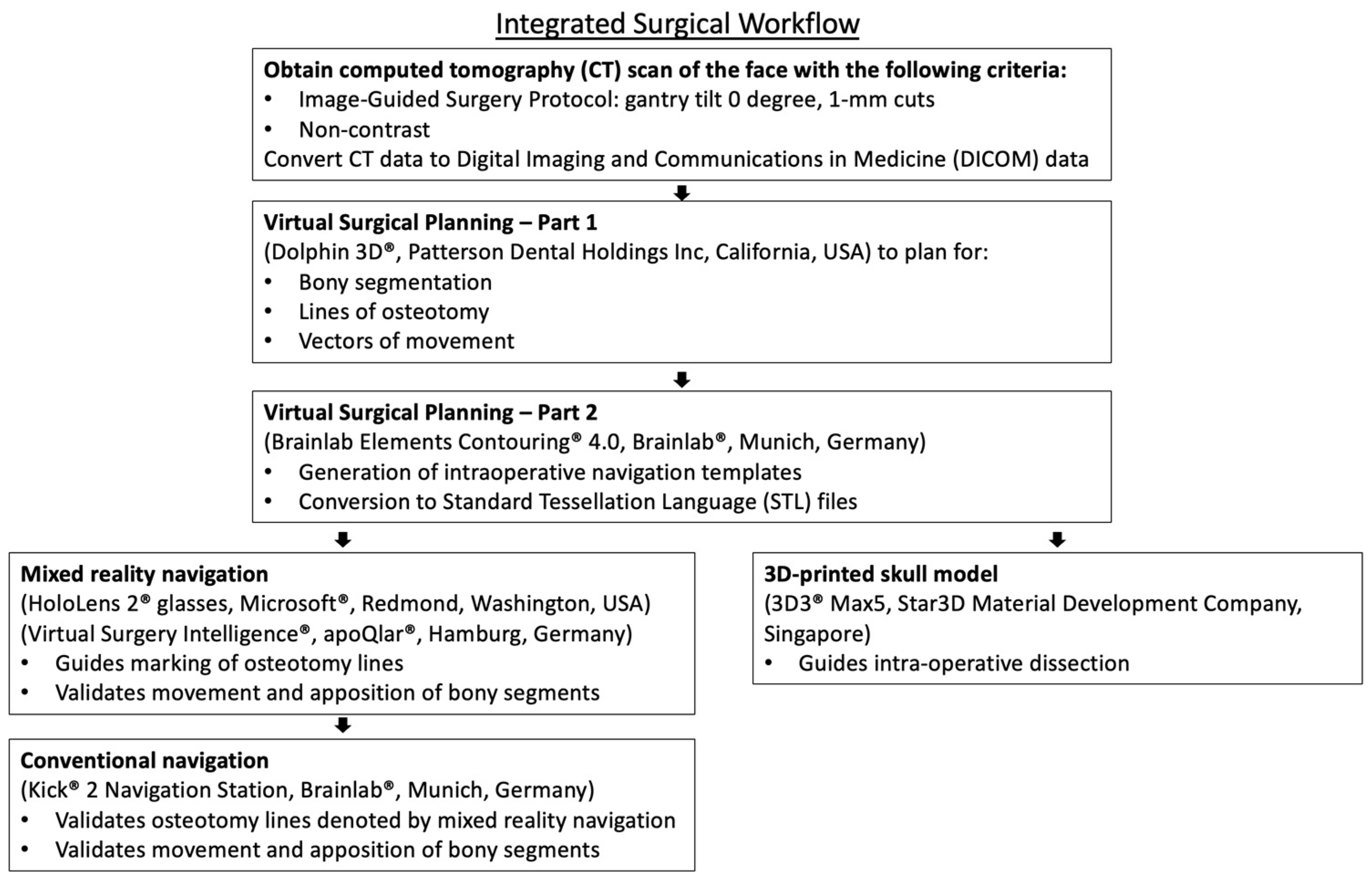

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preoperative Planning

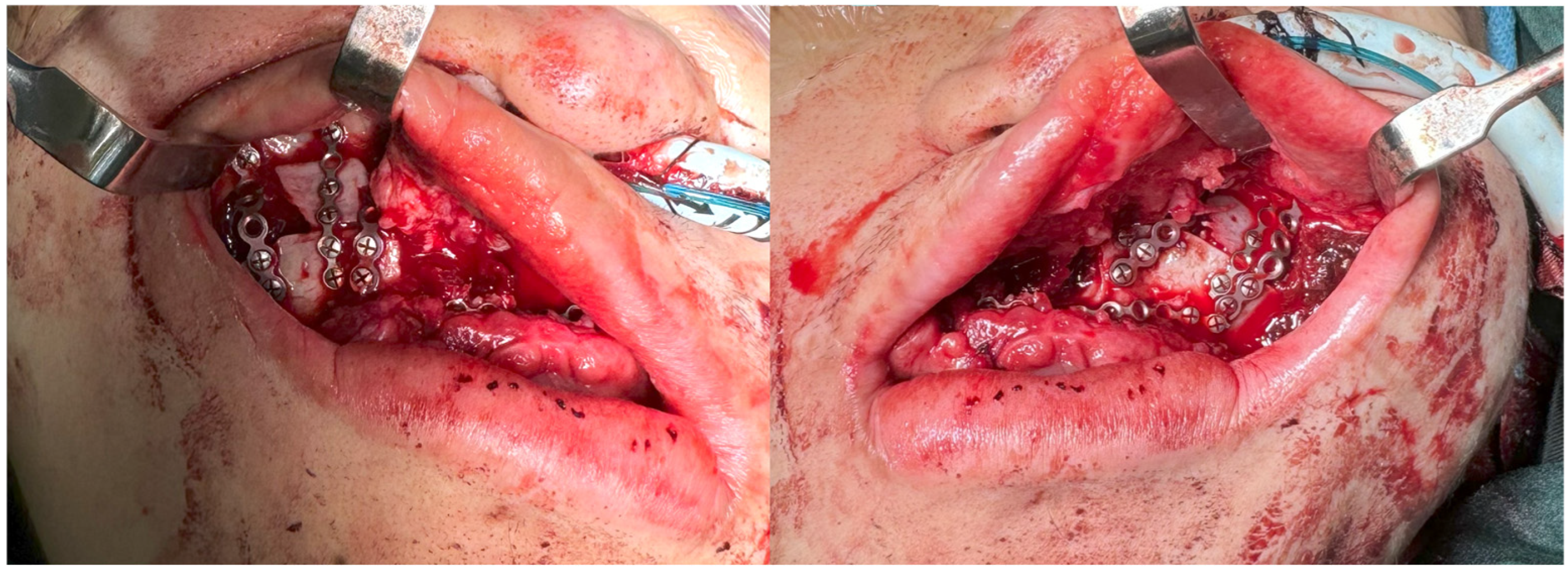

2.2. Intra-Operative Navigation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMF | Craniomaxillofacial |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| MR | Mixed reality |

| STL | Standard Tessellation Language |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

References

- Anderson, B.W.; Kortz, M.W.; Al Kharazi, K. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Skull; StatPearls: Tampa, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dissaux, C.; Diop, V.; Wagner, D.; Talmant, J.-C.; Morand, B.; Bruant-Rodier, C.; Ruffenach, L.; Grollemund, B. Aesthetic and Psychosocial Impact of Dentofacial Appearance after Primary Rhinoplasty for Cleft Lip and Palate. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 49, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liang, H.; Qi, Z.; Jin, X. A Prospective Investigation of Patient Satisfaction and Psychosocial Status Following Facial Bone Contouring Surgery Using the FACE-Q. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.A.; Hobar, C.P. Common Craniofacial Anomalies: Conditions of Craniofacial Atrophy/Hypoplasia and Neoplasia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2003, 111, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almasri, A.M.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Sultan, K.; Aljabban, O.; Zakaria, A.S.; Alhaffar, J.B.; Almasri, A.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Zakaria, A.S., Sr. Evaluation of Satisfaction Levels Following Orthognathic Treatment in Adult Patients: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e73846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, S.; De Fazio, G.R.; Committeri, U.; Spinelli, R.; Nocera, M.; Carraturo, E.; Salzano, G.; Arena, A.; Abbate, V.; Bonavolonta, P.; et al. Mandibular Reconstruction after Post-Traumatic Complex Fracture: Comparison Analysis between Traditional and Virtually Planned Surgery. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 126, 102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveggi, E.; Gerbino, G.; Autorino, U.; Novaresio, A.; Ramieri, G.; Zavattero, E. Accuracy of Intraoperative Navigation for Orbital Fracture Repair: A Retrospective Morphometric Analysis. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 51, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfayez, E. Current Trends and Innovations in Oral and Maxillofacial Reconstruction. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2025, 31, e947152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, E.Z.; Koh, Y.P.; Hing, E.C.H.; Low, J.R.; Shen, J.Y.; Wong, H.C.; Sundar, G.; Lim, T.C. Computer-Assisted Navigational Surgery Improves Outcomes in Orbital Reconstructive Surgery. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2012, 23, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, C.; Schicho, K.; Ploder, O.; Yerit, K.; Watzinger, F.; Ewers, R.; Baumann, A.; Wagner, A. Point-to-Point Computer-Assisted Navigation for Precise Transfer of Planned Zygoma Osteotomies from the Stereolithographic Model into Reality. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, M.; Panwar, S. Role of Navigation in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: A Surgeon’s Perspectives. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2021, 13, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; You, T.-K.; Lee, J.-Y. Modification of Planned Postoperative Occlusion in Orthognathic Surgery, Based on Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing–Engineered Preoperative Surgical Simulation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.; Laviv, A.; Berman, P.; Nashef, R.; Abu-Tair, J. Mandibular Reconstruction Using Stereolithographic 3-Dimensional Printing Modeling Technology. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2009, 108, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, S.; Sharma, Y.; Jain, N.; Satpathy, M.; Pillai, A.K. Use of 3-D Printing Technologies in Craniomaxillofacial Surgery: A Review. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 22, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tack, P.; Victor, J.; Gemmel, P.; Annemans, L. 3D-Printing Techniques in a Medical Setting: A Systematic Literature Review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkarat, F.; Tofighi, O.; Jamilian, A.; Fateh, A.; Abbaszadeh, F. Are Virtually Designed 3D Printed Surgical Splints Accurate Enough for Maxillary Reposition as an Intermediate Orthognathic Surgical Guide. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2023, 22, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboit, L.; Tel, A. Software Used for Virtual Surgical Planning. In Atlas of Virtual Surgical Planning and 3D Printing for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo, W.; Mohamad, A.H.; Zazo, H.; Zazo, A.; Alhashemi, M.; Meslmany, A.; Haddad, B. Facial Defects Reconstruction by Titanium Mesh Bending Using 3D Printing Technology: A Report of Two Cases. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 78, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, E.Z.; Gao, Y.; Ngiam, K.Y.; Lim, T.C. Mixed Reality Intraoperative Navigation in Craniomaxillofacial Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 148, 686e–688e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, E.Z.; Yee, T.H.; Gao, Y.; Lu, W.W.; Lim, T.C. Mixed Reality Guided Advancement Osteotomies in Congenital Craniofacial Malformations. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2024, 98, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McJunkin, J.L.; Jiramongkolchai, P.; Chung, W.; Southworth, M.; Durakovic, N.; Buchman, C.A.; Silva, J.R. Development of a Mixed Reality Platform for Lateral Skull Base Anatomy. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, e1137–e1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, J.; Liebmann, F.; Hoch, A.; Snedeker, J.G.; Farshad, M.; Rahm, S.; Zingg, P.O.; Fürnstahl, P. Augmented Reality Based Surgical Navigation of Complex Pelvic Osteotomies—A Feasibility Study on Cadavers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizia, T.; Sultan, K.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Alhafi, Z.M.; Sukari, T. Evaluation of the Relationship between Sagittal Skeletal Discrepancies and Maxillary Sinus Volume in Adults Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, P.N.; Ruas, E.J.; Iliff, N.T. Deep Orbital Reconstruction for Correction of Post-Traumatic Enophthalmos. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1987, 14, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellrich, N.-C.; Rana, M. Navigation and Computer-Assisted Craniomaxillofacial Surgery. In Digital Technologies in Craniomaxillofacial Surgery; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 351–373. [Google Scholar]

- López-Silva, F.A.; Morales-Yépez, H.A.; Caballero-De-La-Peña, U. Fundamentals of Intraoperative Navigation for Facial Fractures. In Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Fundamentals: A Case-Based and Comprehensive Review; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Yuan, J.; Shen, S.G.; Wang, X. A Novel Method of Computer Aided Orthognathic Surgery Using Individual CAD/CAM Templates: A Combination of Osteotomy and Repositioning Guides. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 51, e239–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.K.; Zhao, L.; Morris, D.E.; Alves, P.V. Our Experience with Virtual Craniomaxillofacial Surgery: Planning, Transference and Validation. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2008, 132, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, P.; Liu, R.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Liu, S.; Huo, T.; Xie, M.; Wu, X.; et al. Applications of Mixed Reality Technology in Orthopedics Surgery: A Pilot Study. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 740507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, R.; Oliveira, A.; Terroso, D.; Vilaça, A.; Veloso, R.; Marques, A.; Pereira, J.; Coelho, L. Mixed Reality in the Operating Room: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2024, 48, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, A.; Ito, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Yoshida, S.; Honda, K.; Kawashima, Y.; Fujikawa, T.; Fujii, Y.; Tsutsumi, T. Patient-Specific Virtual and Mixed Reality for Immersive, Experiential Anatomy Education and for Surgical Planning in Temporal Bone Surgery. Auris. Nasus. Larynx 2021, 48, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Kawashima, Y.; Yamazaki, A.; Tsutsumi, T. Application of a Virtual and Mixed Reality-Navigation System Using Commercially Available Devices to the Lateral Temporal Bone Resection. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 72, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teatini, A.; Kumar, R.P.; Elle, O.J.; Wiig, O. Mixed Reality as a Novel Tool for Diagnostic and Surgical Navigation in Orthopaedics. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2021, 16, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadnytskyi, V.; Ghammraoui, B. Experimental Setup for Evaluating Depth Sensors in Augmented Reality Technologies Used in Medical Devices. Sensors 2024, 24, 3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Ortega-Márquez, J.; Fregni, F. Haptic Technology: Exploring Its Underexplored Clinical Applications—A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangano, F.G.; Yang, K.R.; Lerner, H.; Admakin, O.; Mangano, C. Artificial Intelligence and Mixed Reality for Dental Implant Planning: A Technical Note. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2024, 26, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, E.Z.; Ng, H.H.M.; Gao, Y.; Ngiam, K.Y.; Lee, C.T.H.; Lim, T.C. Synergistic Triad of Mixed Reality, 3D Printing, and Navigation in Complex Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010010

Cai EZ, Ng HHM, Gao Y, Ngiam KY, Lee CTH, Lim TC. Synergistic Triad of Mixed Reality, 3D Printing, and Navigation in Complex Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Elijah Zhengyang, Harry Ho Man Ng, Yujia Gao, Kee Yuan Ngiam, Catherine Tong How Lee, and Thiam Chye Lim. 2026. "Synergistic Triad of Mixed Reality, 3D Printing, and Navigation in Complex Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010010

APA StyleCai, E. Z., Ng, H. H. M., Gao, Y., Ngiam, K. Y., Lee, C. T. H., & Lim, T. C. (2026). Synergistic Triad of Mixed Reality, 3D Printing, and Navigation in Complex Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction. Bioengineering, 13(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010010