Advances and Applications of Organ-on-a-Chip and Tissue-on-a-Chip Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

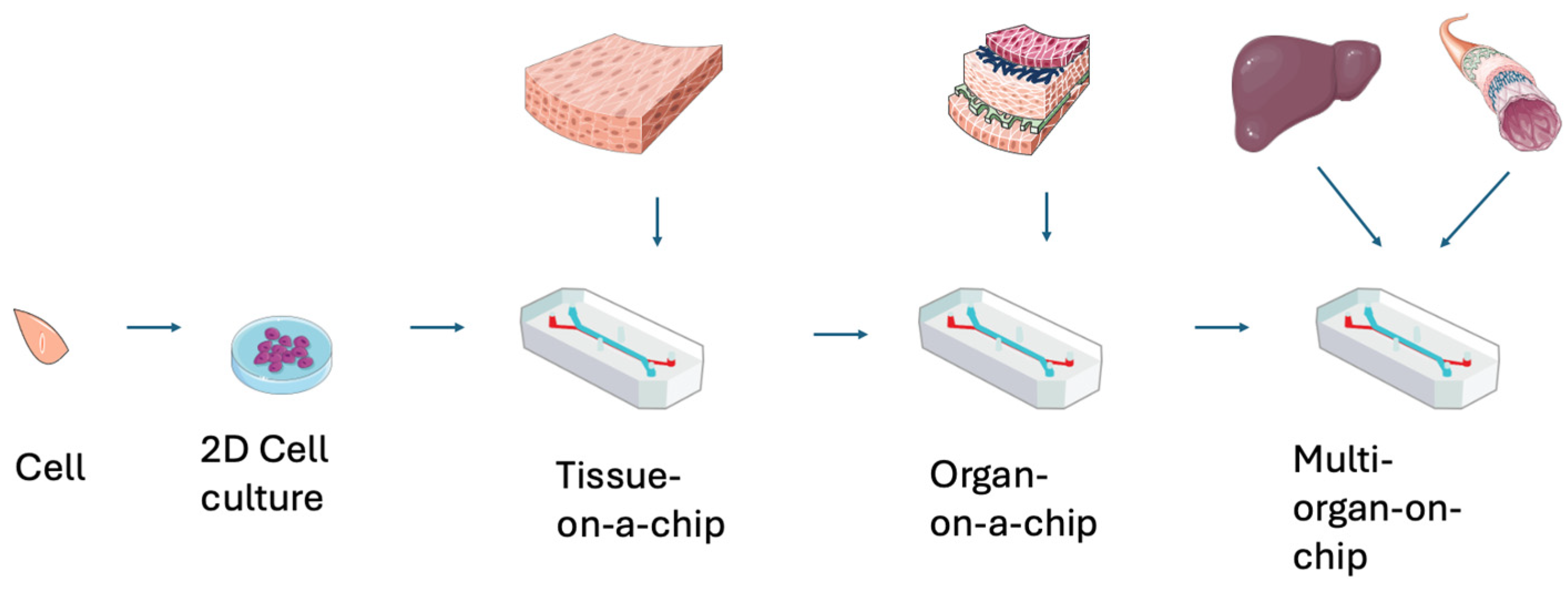

1.1. Overview of the Complicated Nature of Organ-on-a-Chip and Tissue-on-a-Chip Design

1.2. Significance of Integrating Innovative Technology in Regenerative Medicine

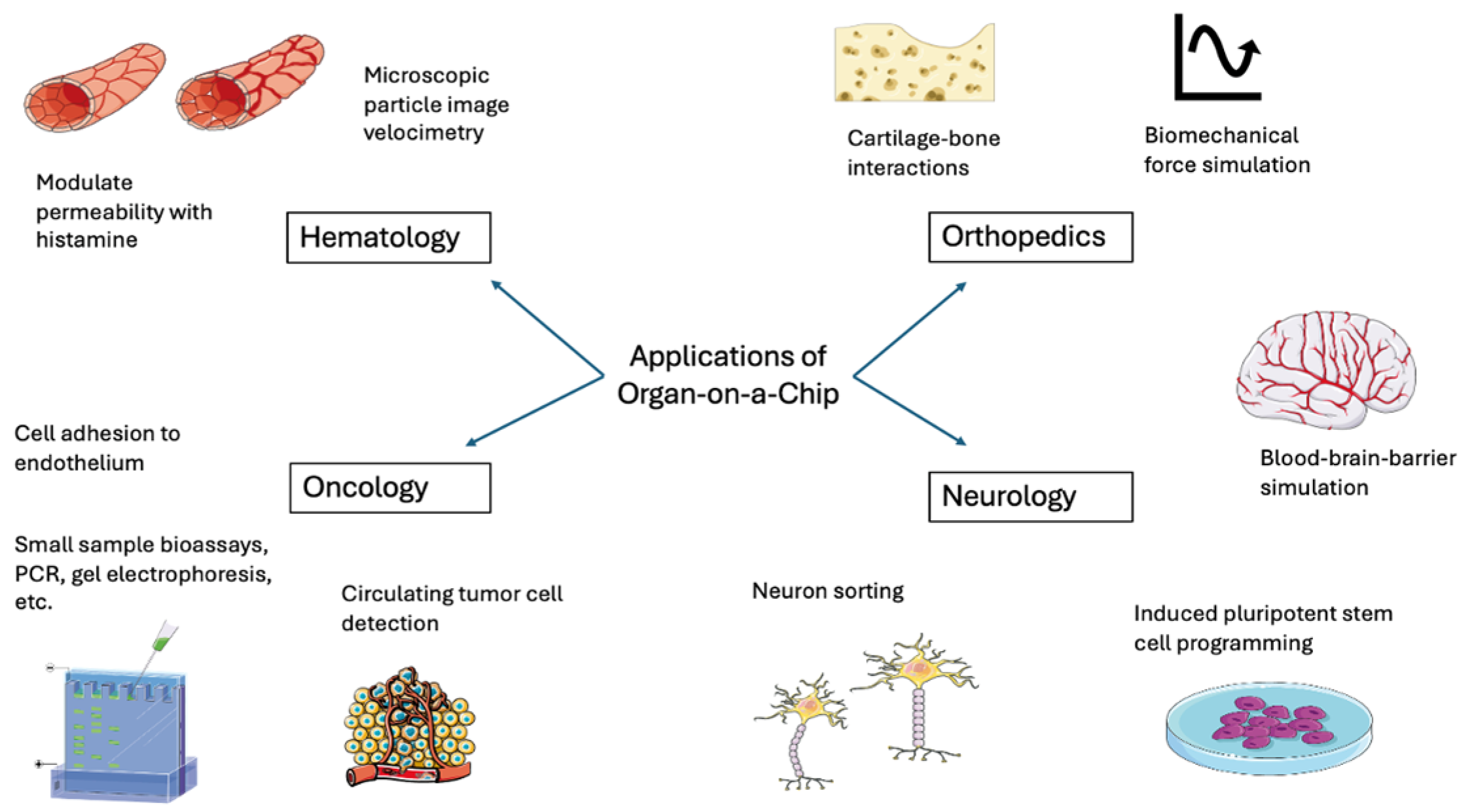

2. Applications of These Innovative Technology

2.1. Hematology and Oncology Applications

2.2. Orthopedics Applications

2.3. Neurology Applications

3. Organ-on-a-Chip 3D Structures

3.1. Structures

3.2. Biomaterials

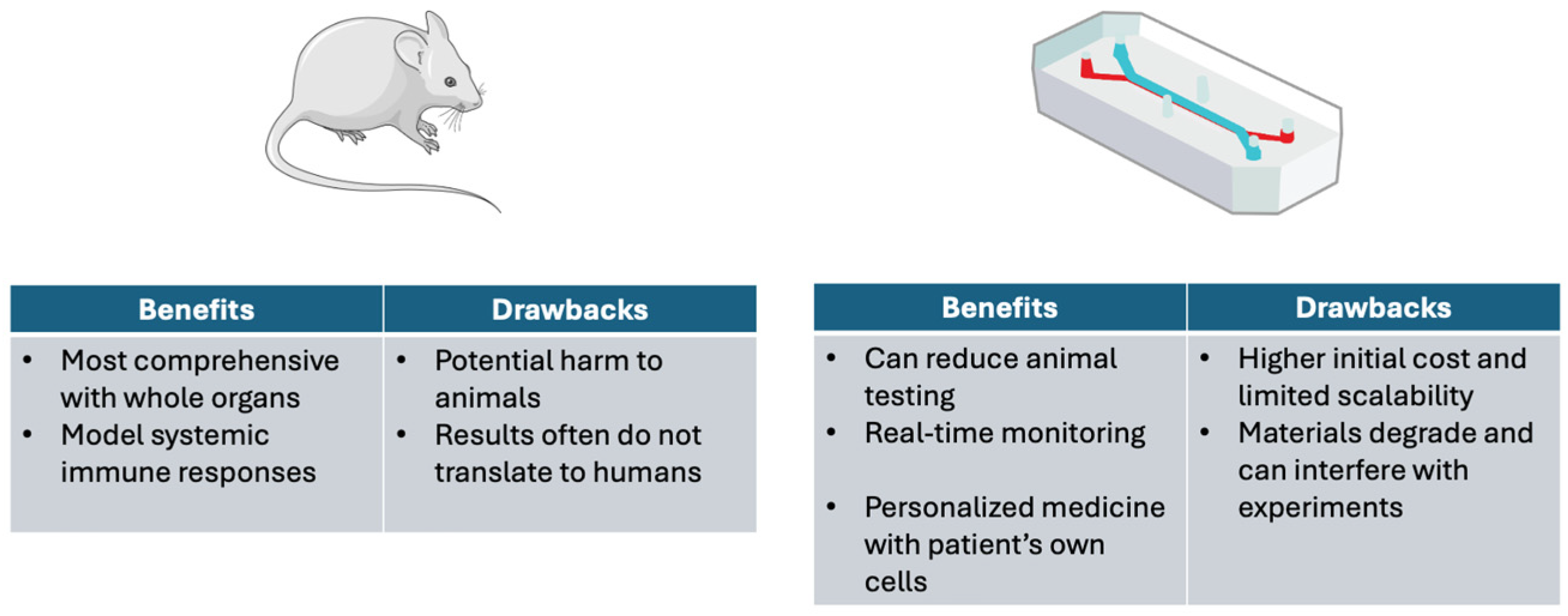

4. Reduction of Animal Testing and Mimicking Mammalian Microenvironments

4.1. Microfluidic Systems and Animal Testing

4.2. Limitations of Animal Studies

4.3. Ethical Considerations

5. Personalized Medicine and Precision Therapeutics in Cancer Patients

5.1. Potential for Personalized Regeneration Techniques

5.2. Revolutionizing Precision Medicine Through Patient-Specific Microenvironments

5.3. Acceleration of Drug Research and Testing Procedures

5.4. Precision Therapy and Drug Selection Advantages in Tumor and Cancer Research

5.5. Challenges in Implementation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahalmani, V.; Sinha, S.; Prakash, A.; Medhi, B. Translational research: Bridging the gap between preclinical and clinical research. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2022, 54, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Gu, Q.; Li, G.; Li, Z.A.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Tuan, R.S. Organoids and organs-on-chips: Recent advances, applications in drug development, and regulatory challenges. Med 2025, 6, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-T.; Rissanen, S.-L.; Peltokangas, M.; Laakkonen, T.; Kettunen, J.; Barthod, L.; Sivakumar, R.; Palojärvi, A.; Junttila, P.; Talvitie, J.; et al. Highly scalable and standardized organ-on-chip platform with TEER for biological barrier modeling. Tissue Barriers 2024, 12, 2315702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, D.; Tosheva, I.; Siegel, T.P.; Cuypers, E.; Honing, M. Technological advances for analyzing the content of organ-on-a-chip by mass spectrometry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1197760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Park, D.; Lee, S.; Gumuscu, B.; Jeon, N.L. Engineering Organ-on-a-Chip to Accelerate Translational Research. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying-Jin, S.; Yuste, I.; González-Burgos, E.; Serrano, D.R. Fabrication of organ-on-a-chip using microfluidics. Bioprinting 2025, 46, e00394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, I.M.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Moita, A.S.; Hori, T.; Kaji, H.; Lima, R.A.; Minas, G. Recent trends of biomaterials and biosensors for organ-on-chip platforms. Bioprinting 2022, 26, e00202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.; Gonçalves, I.; Lage, T.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Minas, G.; Teixeira, S.F.C.F.; Moita, A.S.; Hori, T.; Kaji, H.; Lima, R.A. 3D Printing Techniques and Their Applications to Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, E.; Nebuloni, F.; Rasponi, M.; Occhetta, P. Photo and Soft Lithography for Organ-on-Chip Applications. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2022; 19p. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, I.; Souza, A.; Sousa, P.; Ribeiro, J.; Castanheira, E.M.S.; Lima, R.; Minas, G. Properties and Applications of PDMS for Biomedical Engineering: A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.; Wada, S.; Tanaka, S.; Takeda, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Tsubota, K.-I.; Imai, Y.; Yamaguchi, T. In vitro blood flow in a rectangular PDMS microchannel: Experimental observations using a confocal micro-PIV system. Biomed. Microdevices 2008, 10, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, B.H.; Park, J.; Destgeer, G.; Jung, J.H.; Sung, H.J. Generation of Dynamic Free-Form Temperature Gradients in a Disposable Microchip. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 11568–11574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaro, A.E.; Di Giuseppe, D.; Kermanizadeh, A.; Crespo, A.M.; Mencattini, A.; Ghibelli, L.; Mancini, V.; Wlodarczyk, K.L.; Hand, D.P.; Martinelli, E.; et al. Polylactic is a Sustainable, Low Absorption, Low Autofluorescence Alternative to Other Plastics for Microfluidic and Organ-on-Chip Applications. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 6693–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, A.; Khan, S.; Didar, T.F. Conventional and emerging strategies for the fabrication and functionalization of PDMS-based microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 3053–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Feng, L.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X.; Wen, W.; Gong, X. Organ-on-a-chip: Recent breakthroughs and future prospects. Biomed. Eng. Online 2020, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kankala, R.K.; Wang, S.-B.; Chen, A.-Z. Multi-Organs-on-Chips: Towards Long-Term Biomedical Investigations. Molecules 2019, 24, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Nadda, R.; Repaka, R. Advances and challenges in organ-on-chip technology: Toward mimicking human physiology and disease in vitro. Med Biol. Eng. Comput. 2024, 62, 1925–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronaldson-Bouchard, K.; Teles, D.; Yeager, K.; Tavakol, D.N.; Zhao, Y.; Chramiec, A.; Tagore, S.; Summers, M.; Stylianos, S.; Tamargo, M.; et al. A multi-organ chip with matured tissue niches linked by vascular flow. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingber, D.E. Human organs-on-chips for disease modelling, drug development and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.A.; Chapman, R.; Kings, H.; Allard, J.; Barron-Hastings, J.; Pajtler, K.W.; Sill, M.; Pfister, S.; Grundy, R.G. Limitations of current in vitro models for testing the clinical potential of epigenetic inhibitors for treatment of pediatric ependymoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 36530–36541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, N.; Kundu, B.; Kundu, S.C.; Reis, R.L.; Correlo, V. In Vitro Cancer Models: A Closer Look at Limitations on Translation. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirifar, L.; Shamloo, A.; Nasiri, R.; de Barros, N.R.; Wang, Z.Z.; Unluturk, B.D.; Libanori, A.; Ievglevskyi, O.; Diltemiz, S.E.; Sances, S.; et al. Brain-on-a-chip: Recent advances in design and techniques for microfluidic models of the brain in health and disease. Biomaterials 2022, 285, 121531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, B.; Han, K.; Cao, H.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Mao, M.; Zhu, H.; Cai, H.; Li, D.; He, J. Heart-on-a-chip systems with tissue-specific functionalities for physiological, pathological, and pharmacological studies. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 24, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsbecker, P.; Adiels, C.B.; Goksör, M. Liver-on-a-chip devices: The pros and cons of complexity. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2022, 323, G188–G204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A.; Mummery, C.L.; Passier, R.; Van Der Meer, A.D. Personalised organs-on-chips: Functional testing for precision medicine. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, E.Y.; Lai, F.B.; Cheung, K.; Radisic, M. Organs-on-a-chip: A union of tissue engineering and microfabrication. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Luo, Z.; Lin, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Sensors-integrated organ-on-a-chip for biomedical applications. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 10072–10099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.A.; Hartse, B.X.; Asli, A.E.N.; Taghavimehr, M.; Hashemi, N.; Shirsavar, M.A.; Montazami, R.; Alimoradi, N.; Nasirian, V.; Ouedraogo, L.J.; et al. Advancement of Sensor Integrated Organ-on-Chip Devices. Sensors 2021, 21, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadifar, Z.; Charrez, B.; Almeida, M.; Robben, S.; Pilobello, K.; van der Graaf-Mas, J.; Marquez, S.L.; Ferrante, T.C.; Shcherbina, K.; Gould, R.; et al. Organ chips with integrated multifunctional sensors enable continuous metabolic monitoring at controlled oxygen levels. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 265, 116683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Aleman, J.; Shin, S.R.; Kilic, T.; Kim, D.; Shaegh, S.A.M.; Massa, S.; Riahi, R.; Chae, S.; Hu, N.; et al. Multisensor-integrated organs-on-chips platform for automated and continual in situ monitoring of organoid behaviors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2293–E2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S.; Johansson, S.; Tjell, A.; Werr, G.; Mayr, T.; Tenje, M. In-Line Analysis of Organ-on-Chip Systems with Sensors: Integration, Fabrication, Challenges, and Potential. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 2926–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Sasaki, N.; Ato, M.; Hirakawa, S.; Sato, K.; Sato, K. Microcirculation-on-a-Chip: A Microfluidic Platform for Assaying Blood- and Lymphatic-Vessel Permeability. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, S.; Poudel, C.; Adhikari, R.; Luo, K.Q. Applications of Microfluidics and Organ-on-a-Chip in Cancer Research. Biosensors 2022, 12, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Nagrath, S. Microfluidics and cancer: Are we there yet? Biomed. Microdevices 2013, 15, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.M.; Oner, E.; Ward, M.P.; Hurley, S.; Henderson, B.D.; Lewis, F.; Finn, S.P.; Fitzmaurice, G.J.; O’LEary, J.J.; O’TOole, S.; et al. A comparative study of circulating tumor cell isolation and enumeration technologies in lung cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 2014–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W.; Cavnar, S.P.; Walker, A.C.; Luker, K.E.; Gupta, M.; Tung, Y.-C.; Luker, G.D.; Takayama, S. Microfluidic Endothelium for Studying the Intravascular Adhesion of Metastatic Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Gong, J.; Cui, W.; Li, C.; Yu, M.; Ye, H.; Cui, Z.; Chen, J.; He, Y.; Liu, A.; et al. Developments of microfluidics for orthopedic applications: A review. Smart Mater. Med. 2023, 4, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Khorshidi, S.; Karkhaneh, A. Engineering of gradient osteochondral tissue: From nature to lab. Acta Biomater. 2019, 87, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibey, R.; Arias, J.E.R.; Striebel, J.; Busskamp, V. Microfluidics for Neuronal Cell and Circuit Engineering. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 14842–14880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Helm, M.W.; van der Meer, A.; Eijkel, J.C.; van den Berg, A.; Segerink, L.I. Microfluidic organ-on-chip technology for blood-brain barrier research. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4, e1142493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, D.; Shepherd, T.G. Molecular and cellular mechanisms controlling integrin-mediated cell adhesion and tumor progression in ovarian cancer metastasis: A review. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2022, 39, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żuchowska, A.; Baranowska, P.; Flont, M.; Brzózka, Z.; Jastrzębska, E. Review: 3D cell models for organ-on-a-chip applications. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1301, 342413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolowska, P.; Zukowski, K.; Janikiewicz, J.; Jastrzebska, E.; Dobrzyn, A.; Brzozka, Z. Islet-on-a-chip: Biomimetic micropillar-based microfluidic system for three-dimensional pancreatic islet cell culture. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 183, 113215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Extracellular matrix: An important regulator of cell functions and skeletal muscle development. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, R.; Lee, C.M.; Shugart, E.C.; Benedetti, M.; Charo, R.A.; Gartner, Z.; Hogan, B.; Knoblich, J.; Nelson, C.M.; Wilson, K.M.; et al. Human organoids: A new dimension in cell biology. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobuszewska, A.; Kolodziejek, D.; Wojasinski, M.; Jastrzebska, E.; Ciach, T.; Brzozka, Z. Lab-on-a-chip system integrated with nanofiber mats used as a potential tool to study cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2021, 330, 129291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osório, L.A.; Silva, E.; Mackay, R.E. A Review of Biomaterials and Scaffold Fabrication for Organ-on-a-Chip (OOAC) Systems. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danku, A.E.; Dulf, E.-H.; Braicu, C.; Jurj, A.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Organ-On-A-Chip: A Survey of Technical Results and Problems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 840674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yoon, T.; Kim, P.; Bekhbat, M.; Kang, S.M.; Rho, H.S.; Ahn, S.I.; Kim, Y. Manufactured tissue-to-tissue barrier chip for modeling the human blood–brain barrier and regulation of cellular trafficking. Lab on a Chip 2023, 23, 2990–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wufuer, M.; Lee, G.H.; Hur, W.; Jeon, B.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, T.H.; Lee, S.H. Skin-on-a-chip model simulating inflammation, edema and drug-based treatment. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, N.; Greek, R.; Greek, J. Are animal models predictive for humans? Philos. Ethic- Humanit. Med. 2009, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsink, M.A.J.; Willemen, N.G.A.; Leijten, J.; Bansal, R.; Shin, S.R. Immune Organs and Immune Cells on a Chip: An Overview of Biomedical Applications. Micromachines 2020, 11, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, P.R.; Lamichhane, A.; Guragain, P.; Luker, G.; Tavana, H. A gravity-driven tissue chip to study the efficacy and toxicity of cancer therapeutics. Lab on a Chip 2024, 24, 5251–5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horejs, C. Organ chips, organoids and the animal testing conundrum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Berlo, D.; van de Steeg, E.; Amirabadi, H.E.; Masereeuw, R. The potential of multi-organ-on-chip models for assessment of drug disposition as alternative to animal testing. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 27, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picollet-D’hahan, N.; Zuchowska, A.; Lemeunier, I.; Le Gac, S. Multiorgan-on-a-Chip: A Systemic Approach To Model and Decipher Inter-Organ Communication. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 788–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.J. FDA Modernization Act 2.0 allows for alternatives to animal testing. Artif. Organs 2023, 47, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D. Current ethical issues in animal research. Physiol. News 2012, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boveri, T. Zur Frage der Entstehung Maligner Tumoren; Gustav Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, K.H. Mutationstheorie der Geschwulst-Entstehung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, A.G. Mutation and Cancer: Statistical Study of Retinoblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, D.J. The two “hit” and multiple “hit” theories of carcinogenesis. Br. J. Cancer 1969, 23, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenman, C.; Stephens, P.; Smith, R.; Dalgliesh, G.L.; Hunter, C.; Bignell, G.; Davies, H.; Teague, J.; Butler, A.; Stevens, C.; et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature 2007, 446, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsberg, L.A.; Absher, D.; Dumanski, J.P. Non-heritable genetics of human disease: Spotlight on post-zygotic genetic variation acquired during lifetime. J. Med. Genet. 2013, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ji, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Huang, M.; Dai, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiang, D.; Fu, G.; Lei, Z.; et al. Organoids and organs-on-chips: Insights into predicting the efficacy of systemic treatment in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vega, F.; Mina, M.; Armenia, J.; Chatila, W.K.; Luna, A.; La, K.C.; Dimitriadoy, S.; Liu, D.L.; Kantheti, H.S.; Saghafinia, S.; et al. Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell 2018, 173, 321–337.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasch, C.A.; Favreau, P.F.; Yueh, A.E.; Babiarz, C.P.; Gillette, A.A.; Sharick, J.T.; Karim, M.R.; Nickel, K.P.; DeZeeuw, A.K.; Sprackling, C.M.; et al. Patient-Derived Cancer Organoid Cultures to Predict Sensitivity to Chemotherapy and Radiation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, D.; Liu, H.; Lin, S.; Jiang, Y. Drug cytotoxicity and signaling pathway analysis with three-dimensional tumor spheroids in a microwell-based microfluidic chip for drug screening. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 898, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobrino, A.; Phan, D.T.T.; Datta, R.; Wang, X.; Hachey, S.J.; Romero-López, M.; Gratton, E.; Lee, A.P.; George, S.C.; Hughes, C.C.W. 3D microtumors in vitro supported by perfused vascular networks. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachey, S.J.; Movsesyan, S.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Burton-Sojo, G.; Tankazyan, A.; Wu, J.; Hoang, T.; Zhao, D.; Wang, S.; Hatch, M.M.; et al. An in vitro vascularized micro-tumor model of human colorectal cancer recapitulates in vivo responses to standard-of-care therapy. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 1333–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; De Ninno, A.; Mencattini, A.; Mermet-Meillon, F.; Fornabaio, G.; Evans, S.S.; Cossutta, M.; Khira, Y.; Han, W.; Sirven, P.; et al. Dissecting Effects of Anti-cancer Drugs and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts by On-Chip Reconstitution of Immunocompetent Tumor Microenvironments. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 3884–3893.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Bai, H.; Rodas, M.; Cao, W.; Oh, C.Y.; Jiang, A.; Nurani, A.; Zhu, D.Y.; Goyal, G.; Gilpin, S.E.; et al. Human organs-on-chips as tools for repurposing approved drugs as potential influenza and COVID19 therapeutics in viral pandemics. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertotti, A.; Papp, E.; Jones, S.; Adleff, V.; Anagnostou, V.; Lupo, B.; Sausen, M.; Phallen, J.; Hruban, C.A.; Tokheim, C.; et al. The genomic landscape of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer. Nature 2015, 526, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetrou, E.P. Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells in cancer research and precision oncology. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overman, M.J.; Lonardi, S.; Wong, K.Y.M.; Lenz, H.-J.; Gelsomino, F.; Aglietta, M.; Morse, M.A.; Van Cutsem, E.; McDermott, R.; Hill, A.; et al. Durable Clinical Benefit with Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in DNA Mismatch Repair–Deficient/Microsatellite Instability–High Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, J.T.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Giangarra, V.; Grzeskowiak, C.L.; Ju, J.; Liu, I.H.; Chiou, S.-H.; Salahudeen, A.A.; Smith, A.R.; et al. Organoid Modeling of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Cell 2018, 175, 1972–1988.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palasantzas, V.E.; Tamargo-Rubio, I.; Le, K.; Slager, J.; Wijmenga, C.; Jonkers, I.H.; Kumar, V.; Fu, J.; Withoff, S. iPSC-derived organ-on-a-chip models for personalized human genetics and pharmacogenomics studies. Trends Genet. 2023, 39, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moore, M.; Sriram, S.; Ku, J.; Li, Y. Advances and Applications of Organ-on-a-Chip and Tissue-on-a-Chip Technology. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010009

Moore M, Sriram S, Ku J, Li Y. Advances and Applications of Organ-on-a-Chip and Tissue-on-a-Chip Technology. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoore, Megan, Sashwat Sriram, Jennifer Ku, and Yong Li. 2026. "Advances and Applications of Organ-on-a-Chip and Tissue-on-a-Chip Technology" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010009

APA StyleMoore, M., Sriram, S., Ku, J., & Li, Y. (2026). Advances and Applications of Organ-on-a-Chip and Tissue-on-a-Chip Technology. Bioengineering, 13(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010009