Urban Floods: Linking the Overloading of a Storm Water Sewer System to Precipitation Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Urban floods are events that cause damage in small catchment areas of less than 100 km² (even less than 10 km²). They are trigged by small-scale rain events with volumes far above design rainfall for the concerned hydrological structures [3].

- Urban floods or pluvial flooding in urban areas is the result of high-intensity or prolonged heavy rainfall leading to overland flow and ponding. They can be produced due to the exceedance or blockage of sewer and drainage systems, or high water levels in receiving watercourses [4].

- Detect the potential SWSS overloading based on the precipitation forecast;

- Identify the heavy precipitation characteristics with the highest prediction capacity for SWSS inundation volume, time, and rate;

- Compare results from pairwise correlation and multi-linear regression (MLR) approaches in predicting SWSS overloading accurately.

2. Data and Methods

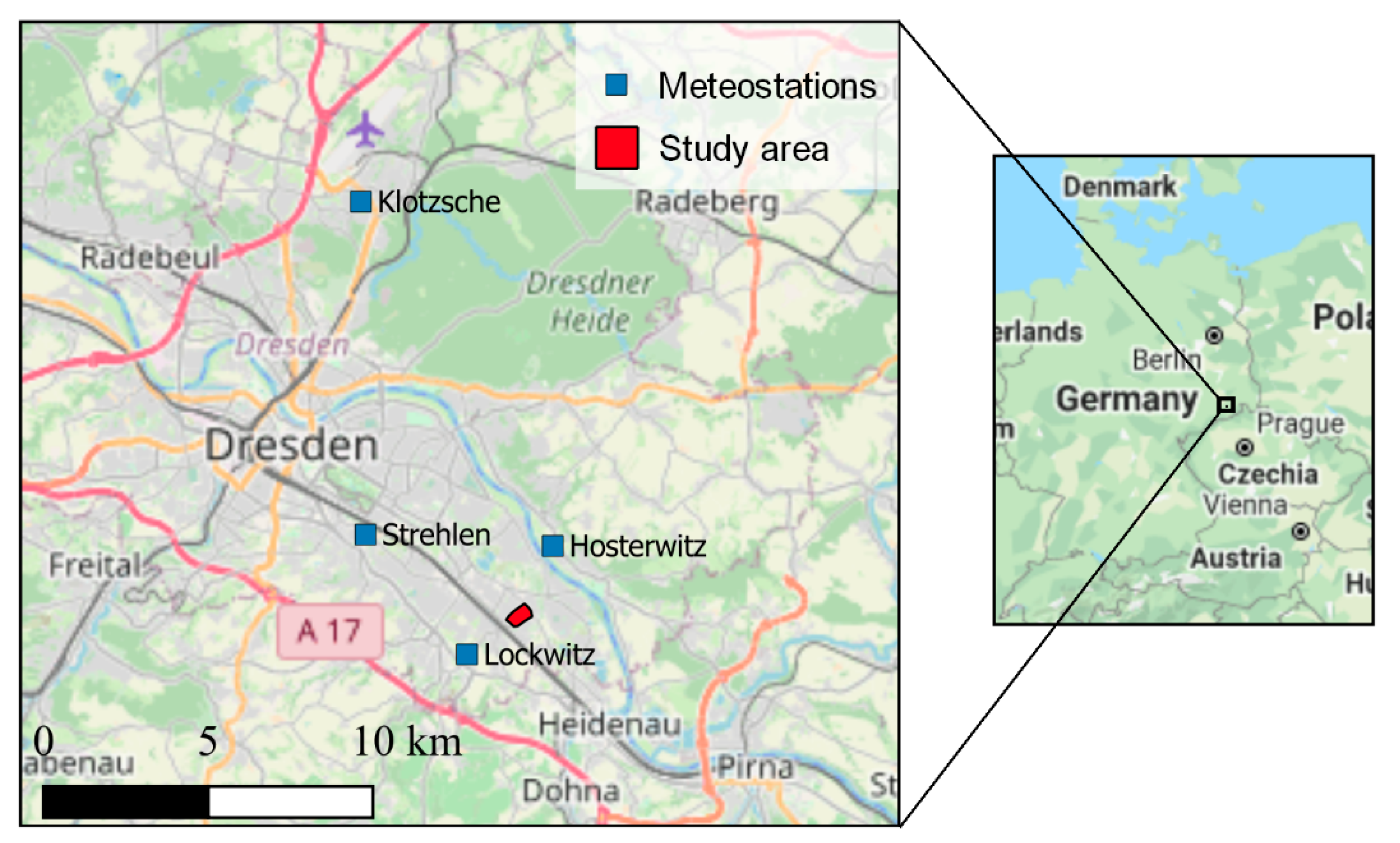

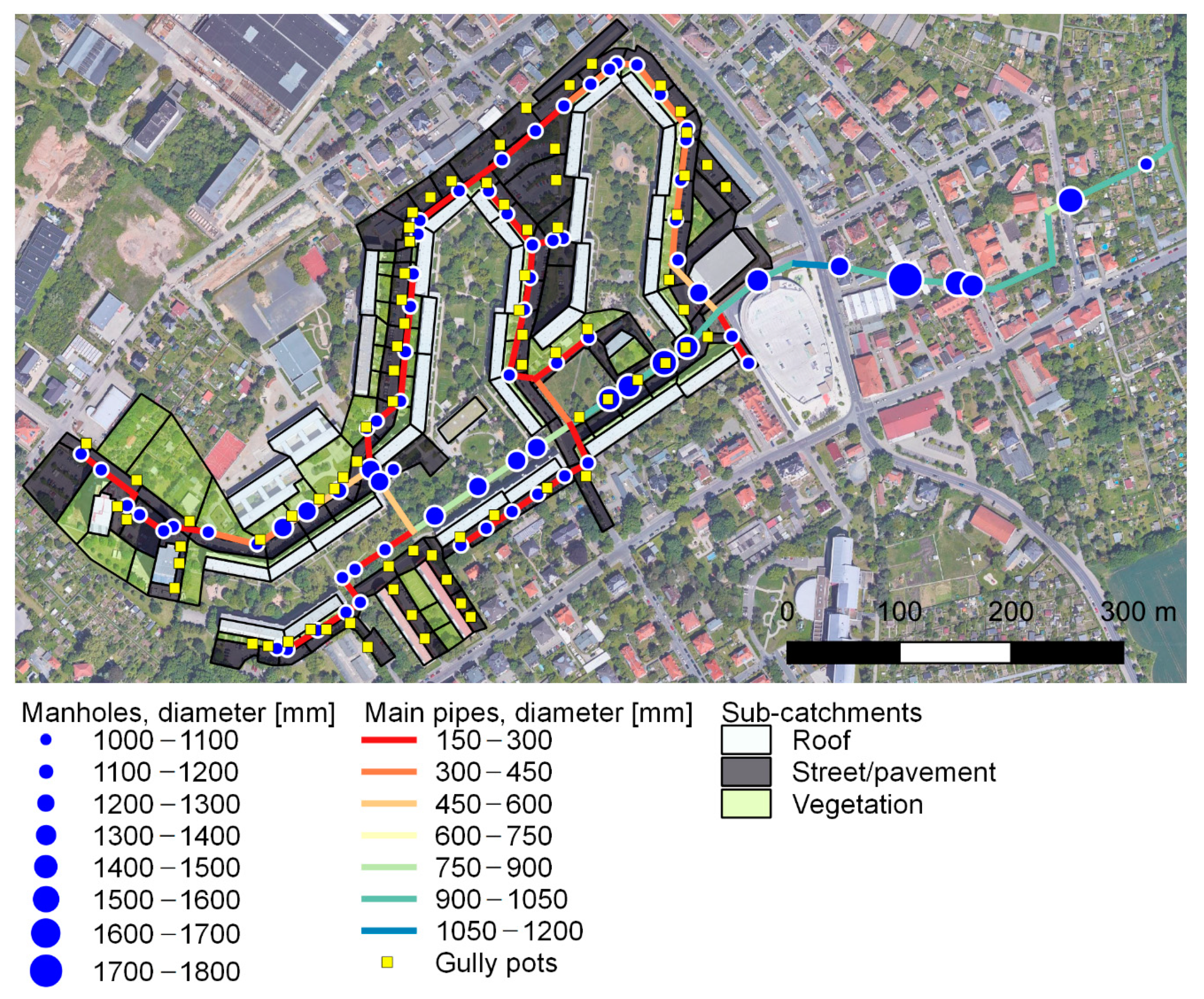

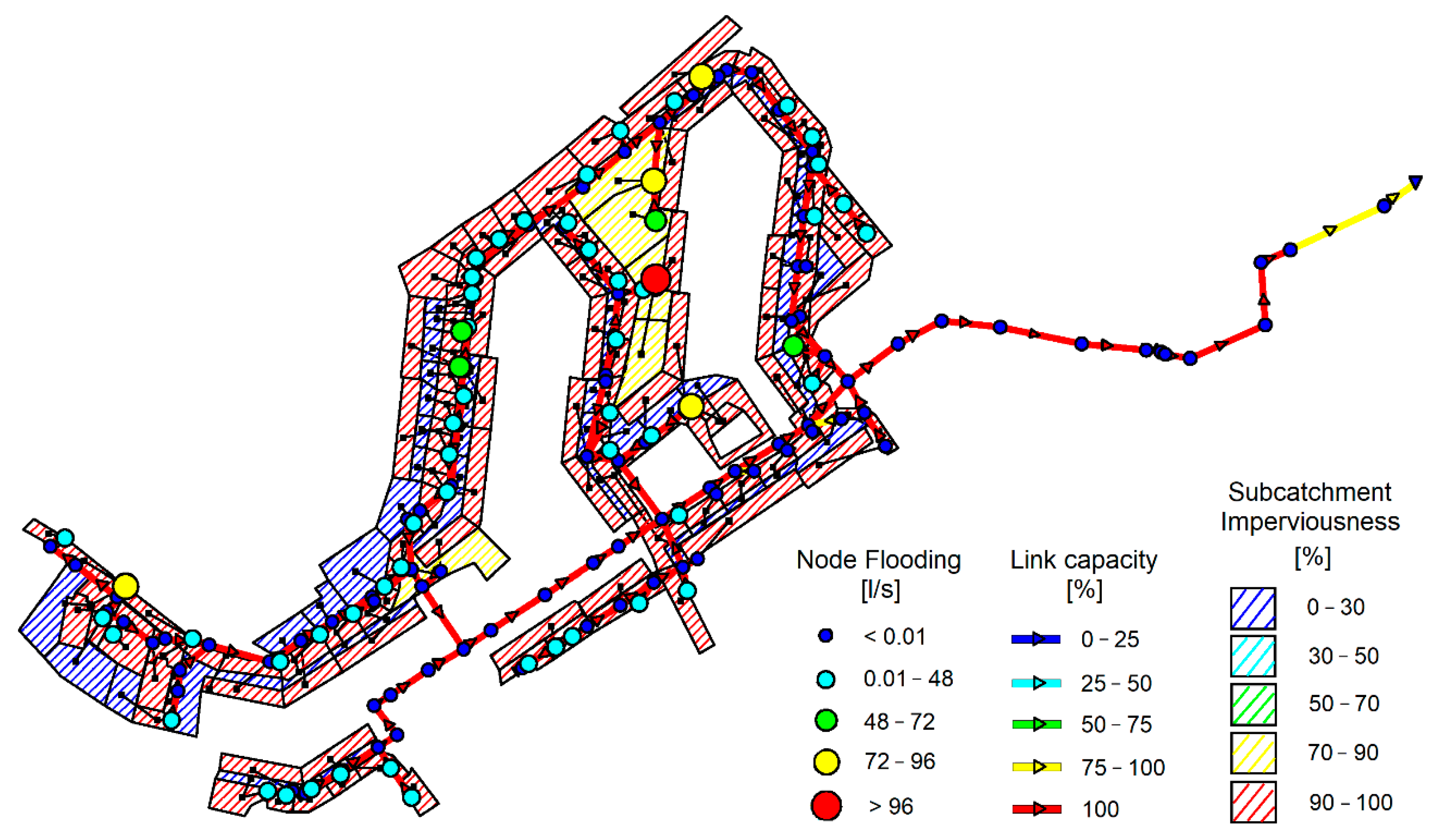

2.1. Study Area and Required Initial Data

2.2. Model Build-Up

2.3. Model Calibration

2.4. Overloading of the Stormwater Sewage System in SWMM

2.5. Statistical Post-Processing of the Results

3. Results and Discussion

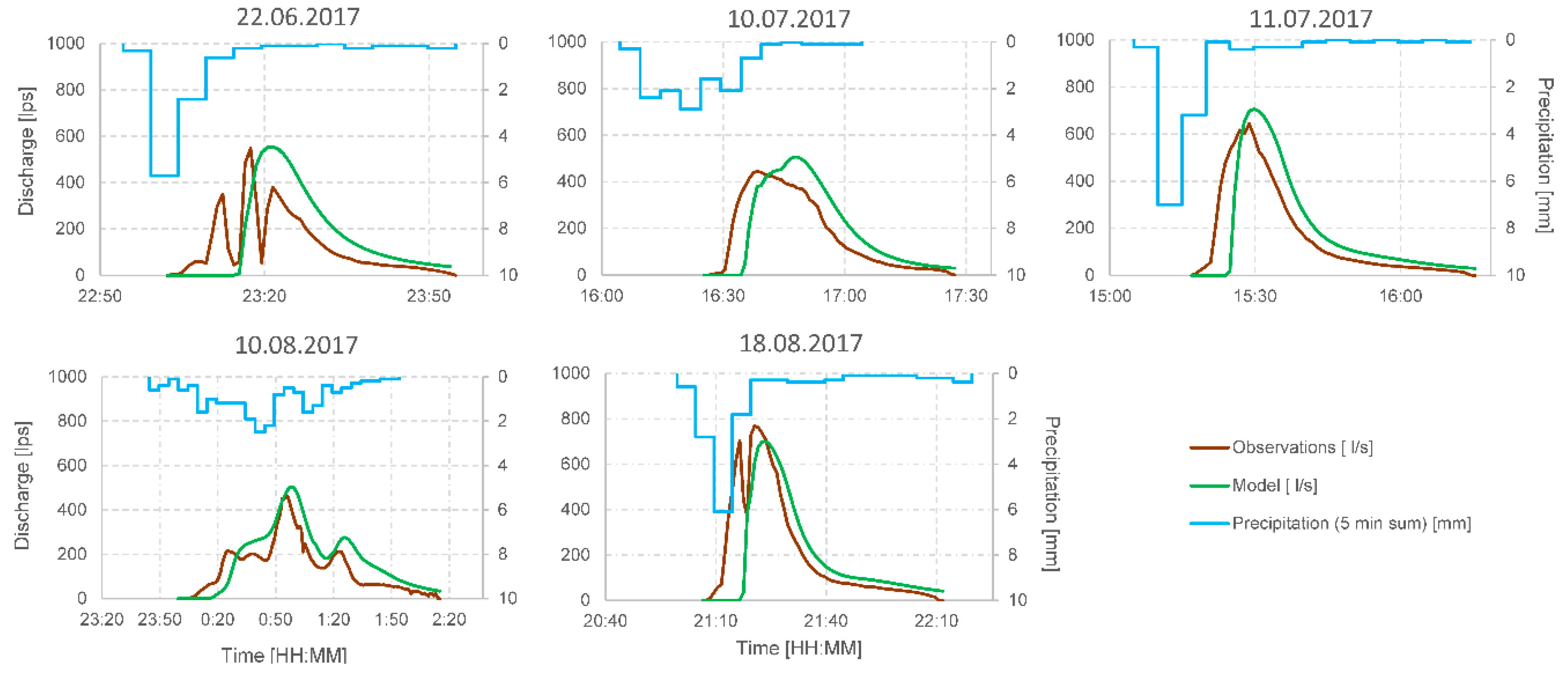

3.1. Model Calibration

3.2. The Model Runs with Various Heavy Precipitation Scenarios

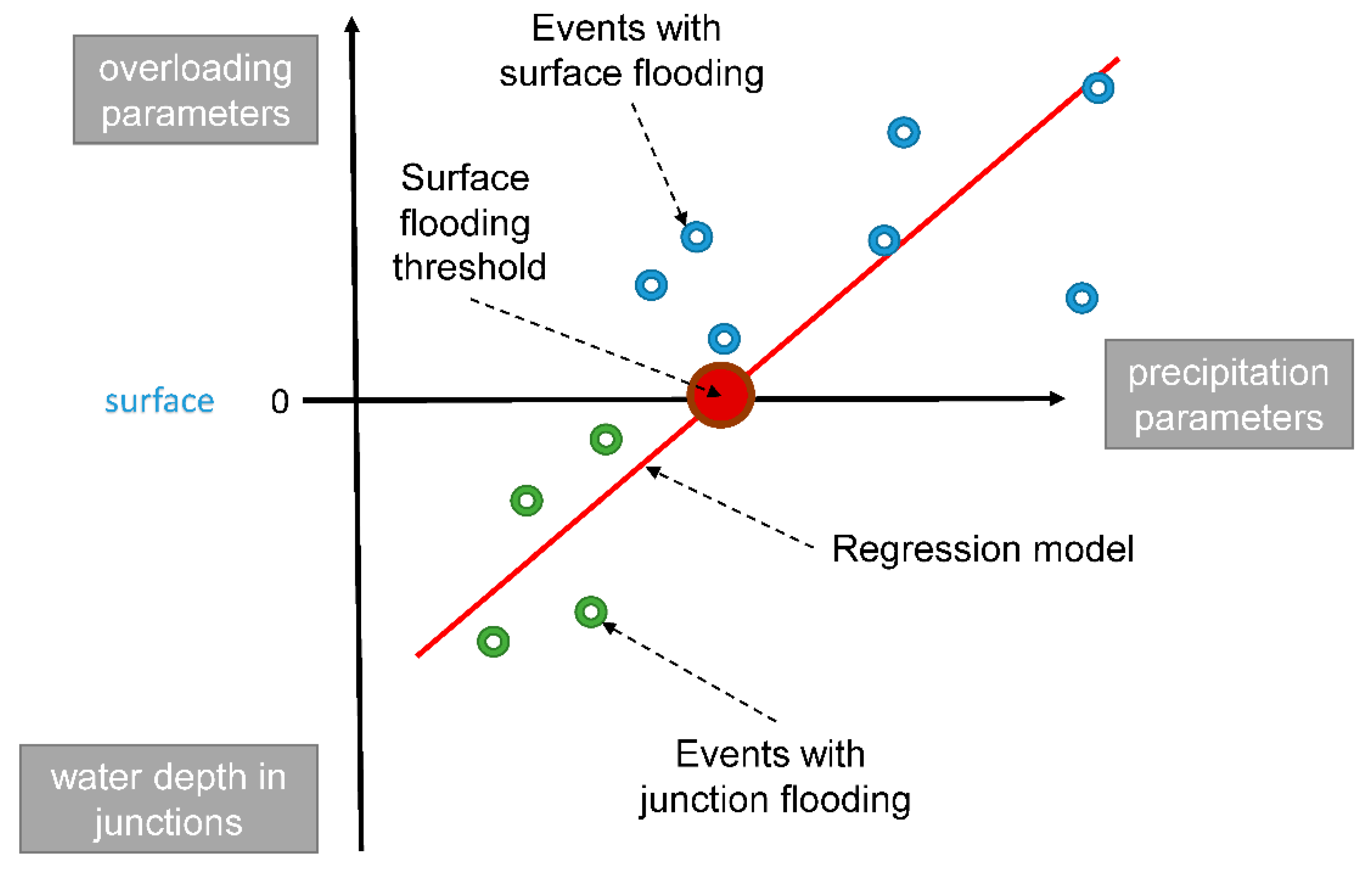

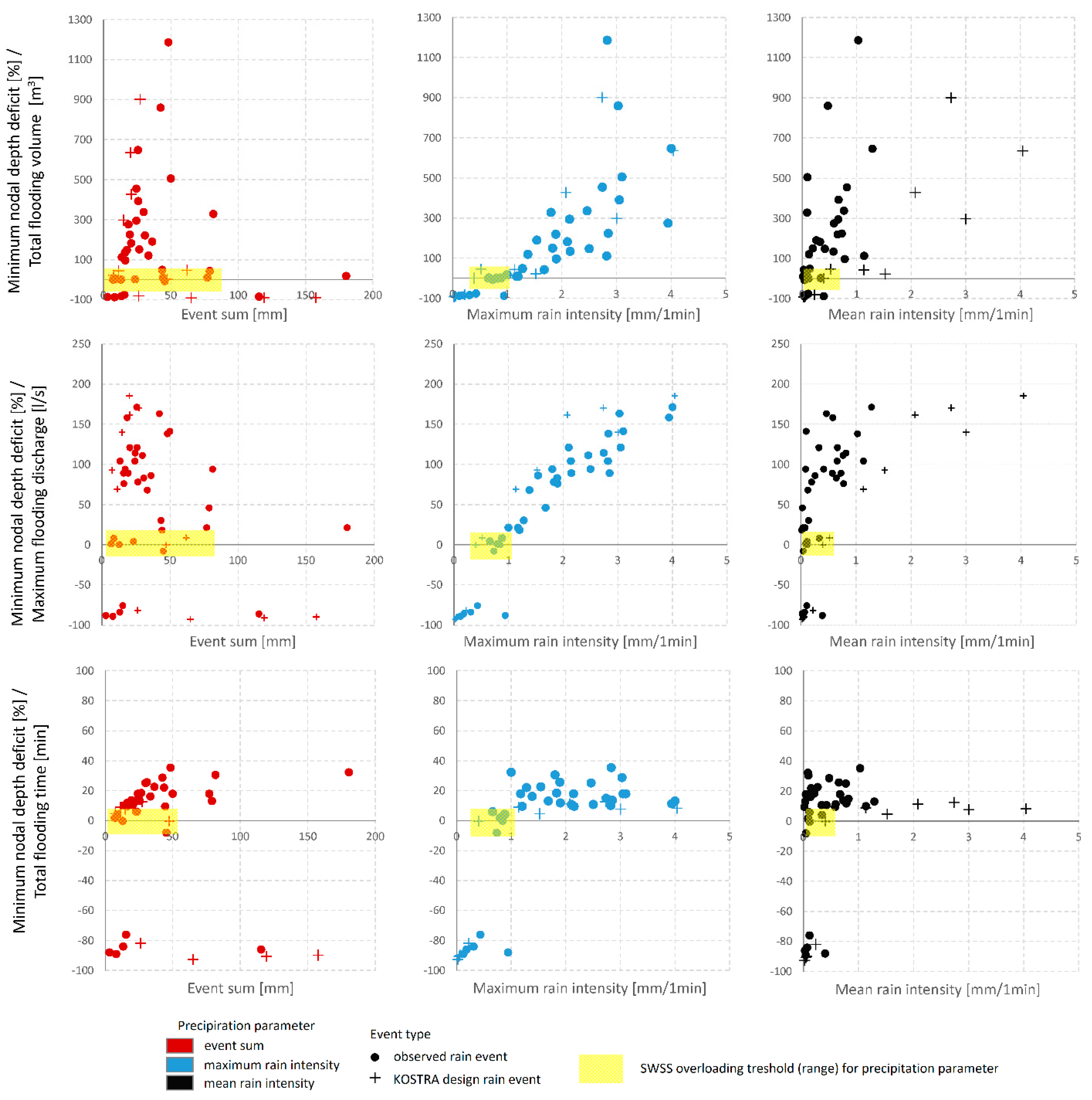

3.3. Detection of “System Overloading” Precipitation Threshold

3.4. Prediction of Overloading Parameters with Multi-Linear Regression

3.5. Influence of the Precipitation Resolution

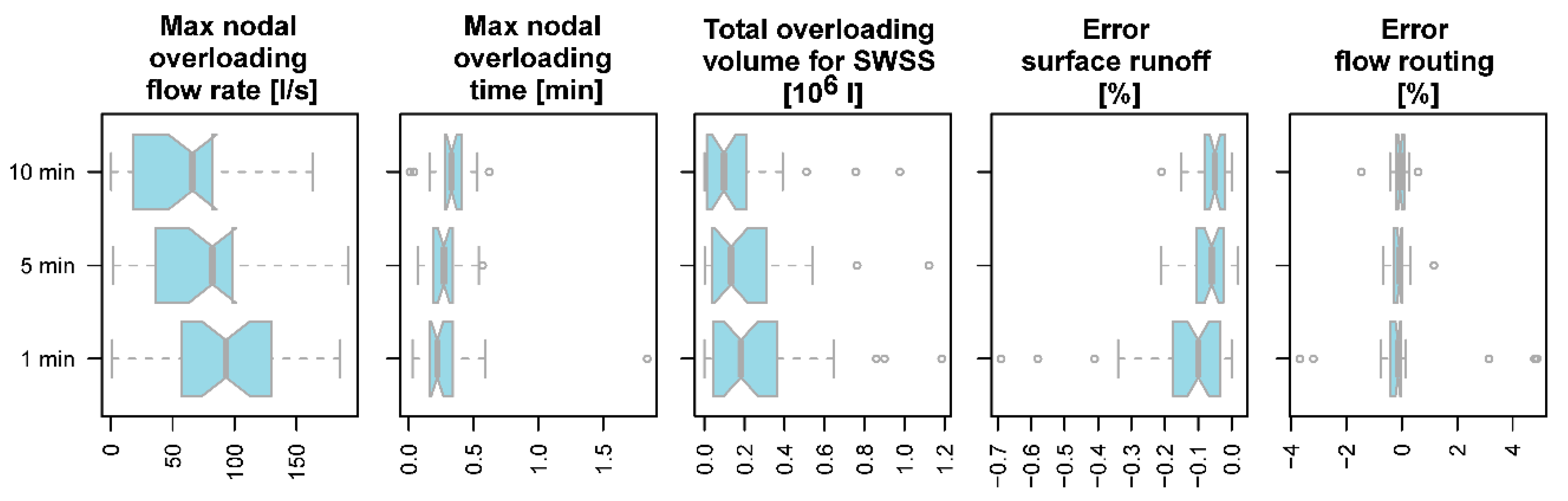

4. Conclusions and Outlook

- The prediction of SWSS overloading using rain forecasts with precipitation characteristics and a proposed graphical approach is, in general, possible. However, the relationship between the upper (surface flooding) and the lower (nodal flooding) parts is quite fuzzy for some precipitation parameters. For the studied SWSS, surface flooding most probably will start after rain with around 1/0.6 mm min−1 of maximum/mean intensity and a total event sum of more than 60 mm.

- The total overloading volume and maximum overloading flow rate showed a higher Pearson’s correlation with the maximum rain intensity (R = 0.67 and R = 0.93, respectively), and for the maximum flooding time, the total rain event sum worked better (R = 0.59).

- MLR with the precipitation characteristics can significantly improve the predictability of the SWSS overloading parameters (with an increase in the Pearson’s correlation coefficient up to 50%). This, however, could require additional data manipulations.

- Observed and designed rain events behave differently in terms of SWSS overloading; thus, the analysis and results should be treated separately.

- The use of the coarser precipitation resolution leads to a decrease in the SWSS overloading volume and maximum flow and increase in the flooding time (relative changes in median values by approximately 20–30%).

- Testing the approach on different catchments, and the extension of the event sample size to obtain more robust statistics;

- In-depth research into SWMM event-based calibration for heavy precipitation events;

- Validating the approach with observations;

- Incorporating models capable of the surface routing of overloaded water.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability

Appendix A

| № | Station | Duration (min) | Sum (mm) | Max Intensity 10 min (mm/min) | Max Intensity 5 min (mm/min) | Max Intensity 1 min (mm/min) | Mean Intensity (mm/min) | K1 | K2 | K3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hosterwitz | 91 | 42 | 19.50 | 10.11 | 3.03 | 0.47 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| 2 | Hosterwitz | 141 | 36 | 10.05 | 6.70 | 1.54 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.17 |

| 3 | Hosterwitz | 4461 | 115 | 1.24 | 0.71 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| 4 | Hosterwitz | 27 | 20 | 11.27 | 10.24 | 2.85 | 0.72 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| 5 | Hosterwitz | 32 | 19 | 14.52 | 11.15 | 3.94 | 0.58 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.15 |

| 6 | Strehlen | 48 | 31 | 11.36 | 6.99 | 1.89 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 0.34 |

| 7 | Strehlen | 314 | 44 | 7.06 | 4.66 | 1.28 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.11 |

| 8 | Strehlen | 12 | 14 | 8.30 | 5.33 | 2.82 | 1.14 | 0.21 | 0.83 | 0.40 |

| 9 | Strehlen | 37 | 24 | 13.02 | 8.46 | 2.14 | 0.66 | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0.31 |

| 10 | Strehlen | 47 | 48 | 15.80 | 11.67 | 2.83 | 1.03 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| 11 | Strehlen | 21 | 16 | 10.47 | 5.78 | 1.90 | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.52 | 0.41 |

| 12 | Strehlen | 1998 | 77 | 6.10 | 3.97 | 1.17 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| 13 | Strehlen | 1024 | 45 | 3.05 | 2.05 | 0.73 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.63 | 0.06 |

| 14 | Strehlen | 28 | 16 | 13.05 | 7.38 | 2.15 | 0.57 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.27 |

| 15 | Klotzsche | 921 | 82 | 12.80 | 8.40 | 1.80 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.05 |

| 16 | Klotzsche | 2330 | 180 | 7.40 | 4.30 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.08 |

| 17 | Klotzsche | 2826 | 44 | 5.30 | 4.00 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.01 |

| 18 | Klotzsche | 525 | 50 | 18.90 | 10.20 | 3.10 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| 19 | Klotzsche | 42 | 17 | 11.00 | 9.40 | 2.50 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.17 |

| 20 | Klotzsche | 63 | 21 | 10.40 | 8.60 | 2.10 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| 21 | Klotzsche | 20 | 26 | 21.60 | 11.10 | 4.00 | 1.28 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.32 |

| 22 | Klotzsche | 137 | 27 | 11.91 | 6.66 | 1.83 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| 23 | Klotzsche | 39 | 30 | 12.85 | 7.99 | 2.46 | 0.77 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

| 24 | Klotzsche | 30 | 25 | 12.34 | 10.47 | 2.74 | 0.82 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| 25 | Klotzsche | 267 | 33 | 12.01 | 6.15 | 1.38 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| 26 | Klotzsche | 2674 | 79 | 6.92 | 5.43 | 1.68 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| 27 | Klotzsche | 39 | 26 | 15.63 | 9.45 | 3.05 | 0.67 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| 28 | Hosterwitz | 82 | 7 | 4.84 | 3.12 | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| 29 | Strehlen | 204 | 13 | 2.17 | 1.12 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| 30 | Strehlen | 213 | 23 | 4.26 | 2.67 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.17 |

| 31 | Hosterwitz | 212 | 8 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.32 |

| 32 | Hosterwitz | 143 | 16 | 3.70 | 1.94 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.25 |

| 33 | Hosterwitz | 8 | 3 | 3.14 | 2.54 | 0.94 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.42 |

| 34 | Strehlen | 27 | 9 | 4.72 | 2.83 | 0.88 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.70 | 0.38 |

| 35 | Klotzsche | 117 | 13 | 3.57 | 2.37 | 0.84 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.64 | 0.13 |

| 36 | Kostra RP2 | 5 | 8 | 15.20 | 7.60 | 1.52 | 1.52 | 0.20 | - | - |

| 37 | Kostra RP20 | 5 | 15 | 30.00 | 15.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.20 | - | - |

| 38 | Kostra RP100 | 5 | 20 | 40.40 | 20.20 | 4.04 | 4.04 | 0.20 | - | - |

| 39 | Kostra RP2 | 10 | 11 | 11.30 | 5.65 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 0.10 | - | - |

| 40 | Kostra RP20 | 10 | 21 | 20.70 | 10.35 | 2.07 | 2.07 | 0.10 | - | - |

| 41 | Kostra RP100 | 10 | 27 | 27.30 | 13.65 | 2.73 | 2.73 | 0.10 | - | - |

| 42 | Kostra RP2 | 120 | 26 | 2.19 | 1.10 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.008 | - | - |

| 43 | Kostra RP20 | 120 | 47 | 3.95 | 1.98 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.008 | - | - |

| 44 | Kostra RP100 | 120 | 62 | 5.18 | 2.59 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.008 | - | - |

| 45 | Kostra RP2 | 2880 | 65 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.0003 | - | - |

| 46 | Kostra RP20 | 2880 | 120 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.0003 | - | - |

| 47 | Kostra RP100 | 2880 | 158 | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.0003 | - | - |

Appendix B

| № | Max Nodal Overloading Time (min) | Max Nodal Overloading Flow Rate (l/s) | Total Overloading Volume for SWSS (106 l) | Max Relative Nodal Depth (No Flooding) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28.80 | 163.0 | 0.8590 | |

| 2 | 22.80 | 86.0 | 0.1900 | |

| 3 | 86 | |||

| 4 | 13.80 | 89.0 | 0.2240 | |

| 5 | 11.40 | 158.0 | 0.2750 | |

| 6 | 25.80 | 83.0 | 0.2200 | |

| 7 | 22.20 | 30.0 | 0.0480 | |

| 8 | 10.20 | 104.0 | 0.1120 | |

| 9 | 18.00 | 104.0 | 0.2950 | |

| 10 | 35.40 | 138.0 | 1.1860 | |

| 11 | 12.00 | 76.0 | 0.0960 | |

| 12 | 18.00 | 21.0 | 0.0100 | |

| 13 | 8 | |||

| 14 | 9.60 | 89.0 | 0.1340 | |

| 15 | 30.60 | 94.0 | 0.3280 | |

| 16 | 32.40 | 21.0 | 0.0180 | |

| 17 | 9.60 | 18.0 | 0.0100 | |

| 18 | 18.00 | 141.0 | 0.5050 | |

| 19 | 10.80 | 94.0 | 0.1480 | |

| 20 | 10.80 | 121.0 | 0.1820 | |

| 21 | 13.20 | 171.0 | 0.6460 | |

| 22 | 18.60 | 78.0 | 0.1500 | |

| 23 | 25.20 | 111.0 | 0.3370 | |

| 24 | 15.00 | 114.0 | 0.4540 | |

| 25 | 16.20 | 68.0 | 0.1200 | |

| 26 | 13.20 | 46.0 | 0.0430 | |

| 27 | 18.00 | 121.0 | 0.3920 | |

| 28 | 1.80 | 1.0 | 0.0001 | |

| 29 | 84 | |||

| 30 | 6.00 | 4.0 | 0.0010 | |

| 31 | 89 | |||

| 32 | 76 | |||

| 33 | 88 | |||

| 34 | 4.20 | 8.0 | 0.0010 | |

| 35 | 0 | |||

| 36 | 4.80 | 93.0 | 0.0220 | |

| 37 | 7.80 | 140.0 | 0.2970 | |

| 38 | 8.40 | 185.4 | 0.6350 | |

| 39 | 9.00 | 69.4 | 0.0430 | |

| 40 | 11.40 | 161.6 | 0.4280 | |

| 41 | 12.60 | 170.4 | 0.9000 | |

| 42 | 82 | |||

| 43 | 0 | |||

| 44 | 8.8 | 0.0460 | ||

| 45 | 93 | |||

| 46 | 91 | |||

| 47 | 90 |

Appendix C

| Model | Adjusted R2 | Residuals Normality (Shapiro–Wilk Normality Test), p-Value | Variance Autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson Test), p-Value | Variance Homogeneity (Breusch–Pagan Test), p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total overloading volume for SWSS | ||||

| non-transformed 1 | 0.70 | 0.00010 | 0.48 | 0.43 |

| non-transformed 2 | 0.72 | 0.00010 | 0.68 | 0.41 |

| transformed 1 | 0.89 | 0.0300 | 0.34 | 0.56 |

| transformed 2 | 0.91 | 0.070 | 0.38 | 0.51 |

| transformed 3 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 0.20 |

| Max nodal overloading time | ||||

| non-transformed 1 | 0.78 | 0.007 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| non-transformed 2 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 0.62 | 0.740 |

| transformed 1 | 0.89 | 0.280 | 0.57 | 0.94 |

| transformed 2 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.50 |

| Max nodal overloading flow rate | ||||

| non-transformed 1 | 0.91 | 0.470 | 0.60 | 0.87 |

| non-transformed 2 | 0.92 | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.51 |

| transformed 1 | 0.92 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.53 |

| transformed 2 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.45 | 0.72 |

References

- UN. Population Division. The World’s Cities in 2018. Data Booklet. United Nations, New York, ST/ESA/SER.A/417. 2018. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3799524?ln=en (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Shuster, W.; Bonta, J.; Thurston, H.; Warnemuende, E.; Smith, D.R. Impacts of impervious surface on watershed hydrology: A review. Urban Water J. 2005, 2, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einfalt, T.; Hatzfeld, F.; Wägner, A.; Seltmann, J.; Castro, D.; Frerichs, S. URBAS: Forecasting and management of flash floods in urban areas. Urban Water J. 2009, 6, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.; Waller, S.; Astle, G.; Kellagher, R. Mapping space for water: Screening for urban flash flooding. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2008, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, H.T.L.; Pathirana, A. Urbanization and climate change impacts on future urban flooding in Can Tho city, Vietnam. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waikar, M.L.; Undegaonkar Namita, U. Urban Flood Modeling by using EPA SWMM 5′. SRTM Univ. Res. J. Sci. 2015, 1, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hénonin, J.; Russo, B.; Mark, O.; Gourbesville, P. Real-time urban flood forecasting and modelling—A state of the art. J. Hydroinform. 2013, 15, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Supply and Water Resources Division of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Risk Management Research Laboratory and with Assistance from the Consulting Firm of CDM-Smith, Storm Water Management Model 5 (SWMM). 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/water-research/storm-water-management-model-swmm (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Chang, H.-K.; Lin, Y.-J.; Lai, J.-S. Methodology to set trigger levels in an urban drainage flood warning system—An application to Jhonghe, Taiwan. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 63, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaidi, A.; Ermalizar, L.M. Flood simulation using EPA SWMM 5.1 on small catchment urban drainage system. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 229, 04022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Kumar, S. Applicability of SWMM for Semi Urban Catchment Flood modeling using Extreme Rainfall Events. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S. Impact of the Storm Sewer Network Complexity on Flood Simulations According to the Stroke Scaling Method. Water 2018, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, E.; Veldhuis, M.-C.T.; Van De Giesen, N. Spatial and temporal variability of rainfall and their effects on hydrological response in urban areas—A review. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 3859–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchetta, A.D.L.; Coulibaly, P. Recent Advances in Real-Time Pluvial Flash Flood Forecasting. Water 2020, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-H. An Advanced Method to Apply Multiple Rainfall Thresholds for Urban Flood Warnings. Water 2015, 7, 6056–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, D.J.; Jeon, B.H. Development of Flood Nomograph for Inundation Forecasting in Urban Districts. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2013, 13, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thorndahl, S.; Willems, P. Probabilistic modelling of overflow, surcharge and flooding in urban drainage using the first-order reliability method and parameterization of local rain series. Water Res. 2008, 42, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosz, S.; Kiczko, A.; Studziński, J.; Dąbek, L. Hydrodynamic and probabilistic modelling of storm overflow discharges. J. Hydroinform. 2018, 20, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Han, K.Y. Urban Flood Prediction Using Deep Neural Network with Data Augmentation. Water 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; He, P. Approach for evaluating inundation risks in urban drainage systems. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 553, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, J.; Kang, A.; Li, S.; Feng, P. The Effect of Nonstationarity in Rainfall on Urban Flooding Based on Coupling SWMM and MIKE21. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 1535–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, R.; Yin, J.; Yu, D. Linking a Storm Water Management Model to a Novel Two-Dimensional Model for Urban Pluvial Flood Modeling. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Han, K.Y. Inundation Map Prediction with Rainfall Return Period and Machine Learning. Water 2020, 12, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Keum, H.J.; Han, K.Y. Real-Time Urban Inundation Prediction Combining Hydraulic and Probabilistic Methods. Water 2019, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. Planet Dump Retrieved from https://planet.osm.org. 2019. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Microsoft. BingTM Maps Tiles. 2020. Available online: http://ecn.t3.tiles.virtualearth.net/tiles/a{q}.jpeg?g=1 (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Rossman, L.A. Storm Water Management Model. Reference Manual. In Hydraulics; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher Wetterdienst. Annual Regional Averages (Mean Temperature and Precipitation), Daily, Hourly and 10 Minute and 1 Minute Station Data (Mean Temperature, Precipitation) for Germany. DWD Database. 2019. Available online: Ftp://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/CDC/ (accessed on 3 January 2018).

- Deutscher Wetterdienst. Koordinierte Starkniederschlagsregionalisierung und-Auswertung des DWD. KOSTRA-DWD-2010R: Design Precipitation for Germany. 2017. Available online: https://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/CDC/grids_germany/return_periods/precipitation/KOSTRA/KOSTRA_DWD_2010R/ (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Kalberer, P.; Walker, M. QGIS-OpenLayers-Plugin; Sourcepole: Zürich, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, W.J.; Brakensiek, D.L.; Miller, N. Green-ampt Infiltration Parameters from Soils Data. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1983, 109, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System; Open Source Geospatial Foundation: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, L.A.; Wayne, C.H. Storm Water Management Model. Reference Manual. In Hydrology (Revised); U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pina, R.D.; Simões, N.E.; Marques, A.S.; Sousa, J. Floodplain delineation with Free and Open Source Software. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Urban Drainage, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 11–16 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borah, D.K.; Arnold, J.G.; Bera, M.; Krug, E.C.; Liang, X.-Z. Storm Event and Continuous Hydrologic Modeling for Comprehensive and Efficient Watershed Simulations. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2007, 12, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Steinman, A.D. Event and Continuous Hydrologic Modeling with HEC-HMS. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2009, 135, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Liang, J.; Bárdossy, A. Improving the calibration strategy of the physically-based model WaSiM-ETH using critical events. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2012, 57, 1487–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.B.; Chua, L.H.; Shuy, E.B.; Lo, E.; Lim, L.W. Performances of Rainfall-Runoff Models Calibrated over Single and Continuous Storm Flow Events. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2008, 13, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Brüggemann, K.; Seguya, K.D.; Ahmed, E.; Kaeseberg, T.; Dai, H.; Hua, P.; Zhang, J.; Krebs, P. Measuring performance of low impact development practices for the surface runoff management. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2020, 1, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.; Sutcliffe, J. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, M.A.; O’Farrell, P.N. The Assumptions of the Linear Regression Model. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1971, 52, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, J.; Watson, G.S. Testing For Serial Correlation in Least Squares Regression: I. Biometrika 1950, 37, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breusch, T.S.; Pagan, A.R. A Simple Test for Heteroscedasticity and Random Coefficient Variation. Econometrica 1979, 47, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, I. Critical Levels, Statistical Language and Scientific Inference. Found. Stat. Inference 1971, 500–513. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.P.; Cox, D.R. An Analysis of Transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 1964, 26, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeileis, A.; Hothorn, T. Diagnostic Checking in Regression Relationships. R News 2002, 2, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Manning’s Roughness Coefficients for Common Materials. Engineering ToolBox. 2004. Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/mannings-roughness-d_799.html (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Yen, B.C. Hydraulics of Sewer Systems. In Stormwater Collection Systems Design Handbook; McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- Corsmeier, U.; Kalthoff, N.; Barthlott, C.; Aoshima, F.; Behrendt, A.; Di Girolamo, P.; Dorninger, M.; Handwerker, J.; Kottmeier, C.; Mahlke, H.; et al. Processes driving deep convection over complex terrain: A multi-scale analysis of observations from COPS IOP 9c. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wapler, K.; Harnisch, F.; Pardowitz, T.; Senf, F. Characterisation and predictability of a strong and a weak forcing severe convective event—A multi-data approach. Meteorol. Z. 2015, 24, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoben, W.; Freer, J.E.; Woods, R. Technical note: Inherent benchmark or not? Comparing Nash–Sutcliffe and Kling–Gupta efficiency scores. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 4323–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, N.; Blumensaat, F.; Molnar, P.; Fatichi, S.; Burlando, P. Partitioning the impacts of spatial and climatological rainfall variability in urban drainage modeling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, E.; Veldhuis, M.-C.T.; Gaitan, S.; Ochoa-Rodriguez, S.; Van De Giesen, N. Critical scales to explain urban hydrological response: An application in Cranbrook, London. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 2425–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Required Information | Used Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Stormwater sewer system | Position of each element, dimensions, pipe slope, structure shape, roughness | GIS of the sewer system of Dresden, discharge measurements by TU Dresden, correction of manhole/gully pot positions and connection with field survey |

| Surface relief and land cover | Catchment and sub-catchment boundaries and routing to the drainage system, slopes, infiltration parameters, and roughness | Digital Terrain Model (DTM); 1 m resolution; from TU Dresden, Bing, and Google satellite images [25,26]; Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) documentation [27] |

| Climate | Precipitation, temperature | Deutsche Wetterdienst (DWD) and TU Dresden meteostations for climate data [28], Koordinierte Starkniederschlagsregionalisierung und -auswertung (KOSTRA) des DWD for design precipitation [29] |

| Criteria | Range | Formulae | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) | [−∞, 1] NSE = 1—corresponds to a perfect match of modeled discharge to the observed data | Q—flow, m—modeled, o—observed, t—timestep | (1) |

| Kling–Gupta Efficiency (KGE) | [−∞, 1] KGE = 1—a perfect match of modeled discharge to the observed data | is the Pearson correlation coefficient between the simulated and observed flow, is the ratio between the mean simulated and mean observed flow, is the ratio between the simulated and observed flow variance | (2) |

| Peak errors (maximum discharge value and time) | [−∞, +∞] PE = 0—a perfect match between modeled and observed event peak | (3) (4) | |

| Event volume error | [−∞, +∞] VE = 0—a perfect match betweem modeled and observed event volume | (5) |

| Assumptions | Test |

|---|---|

| Linear relationship and independent predictors | Scatter plot, correlation matrix |

| Symmetrical (normal) distribution | Histogram (Shapiro–Wilk test) |

| Normality of the residuals | Histogram, Shapiro–Wilk test |

| Non-autocorrelation of the residuals | Durbin–Watson test |

| Homoscedasticity of variance | Breusch–Pagan test, multi-linear regression diagnostic plots |

| Event | 22 June 2017 | 10 July 2017 | 11 July 2017 | 10 August 2017 | 18 August 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSE (-) | −0.23 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.51 |

| KGE (-) | 0.39 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| Q peak error (%) | 1 | 14 | 10 | 9 | −9 |

| Peak time error (min) | 4 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Volume error (%) | 31 | 12 | 12 | 29 | −8 |

| Duration (min) | Sum (mm) | Imax (mm/min) | Imean (mm/min) | K1 (1/min) | K2 (-) | K3 (-) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | |||||||

| min | 8 | 3.14 | 0.12 | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.013 |

| max | 4461 | 180 | 4.00 | 1.29 | 0.30 | 0.83 | 0.42 |

| Designed | |||||||

| min | 5 | 7.60 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0 | - | - |

| max | 2880 | 158 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.20 | - | - |

| Max Nodal Overloading Time (Min) | Max Nodal Overloading Flow Rate (L/S) | Total Overloading Volume for SWSS (106 L) | Max Relative Nodal Loading (No Flooding) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | ||||

| min | 2 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 |

| max | 35 | 171 | 1.19 | 89 |

| Designed | ||||

| min | 5 | 8.81 | 0.02 | 0 |

| max | 13 | 185 | 0.90 | 93 |

| SWSS Overload/Precipitation Parameters | Duration (min) | Sum (mm) | Imax (mm/min) | Imean (mm/min) | K1 (1/min) | K2 (-) | K3 (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed and designed precipitation | |||||||

| Max nodal overloading time (min) | 0.03 | 0.41 * | −0.22 | −0.17 | −0.46 ** | −0.23 | −0.06 |

| Max nodal overloading flow rate (l/s) | −0.45 ** | −0.29 | 0.89 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.56 *** | −0.12 | 0.30 |

| Total overloading volume for SWSS (106 l) | −0.31 | −0.07 | 0.68 *** | 0.46 ** | 0.16 | −0.25 | 0.28 |

| Observed precipitation only | |||||||

| Max nodal overloading time (min) | 0.11 | 0.59 *** | 0.14 | 0.06 | −0.46 * | - | - |

| Max nodal overloading flow rate (l/s) | −0.48 * | −0.24 | 0.93 *** | 0.64 *** | 0.50 ** | - | - |

| Total overloading volume for SWSS (106 l) | −0.33 | −0.05 | 0.67 *** | 0.54 ** | 0.12 | - | - |

| Parameter | Raw Data | Transformed (Box-Cox) Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | p-Value | λ-Value | Transformation Type | |

| Duration (min) | 0 | 0.02 | −0.1 | ln |

| Sum (mm) | 0 | 0.92 | −0 | ln |

| Imax (mm/min) | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.5 | sqrt |

| Imean (mm/min) | 0 | 0.26 | 0 | ln |

| K1 (1/min) | 0 | 0.31 | 0.4 | sqrt |

| K2 (-) | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.5 | sqrt |

| K3 (-) | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.6 | sqrt |

| Max nodal overloading time (h) | 0 | 0.21 | 0 | ln |

| Max nodal overloading flow rate (l/s) | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.7 | - |

| Total overloading volume for SWSS (106 l) | 0 | 0.43 | 0.3 | sqrt |

| № | Predictors | Transformation | Fitting of MLR Assumptions * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Total overloading volume for SWSS (106 l) | |||||||

| 1 | All | no | X | X | X | V | V |

| 2 | Duration + Imax + K1 + K3 | no | X | X | X | V | V |

| 3 | All | yes | X | X | X | V | V |

| 4 | Duration + Imax + Imean + K1 | yes | X | V | V | V | V |

| 5 | Duration + Sum + Imax | yes | V | V | V | V | V |

| Max nodal overloading time (h) | |||||||

| 1 | All | no | X | X | X | V | V |

| 2 | Duration + Sum + Imax + Imean + K1+ K2 | no | X | X | X | V | V |

| 3 | All | yes | X | V | V | V | V |

| 4 | Sum + K3 | yes | V | V | V | V | V |

| Max nodal overloading flow rate (l/s) | |||||||

| 1 | All | no | X | X | V | V | V |

| 2 | Duration + Imax + K1 + K3 | no | X | X | V | V | V |

| 3 | All | yes | X | V | V | V | V |

| 4 | Sum + Imax + K2 | yes | V | V | V | V | V |

| SWSS Overloading Parameter | Pairwise Max Correlation | MRL Correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed + Designed Precipitation | Observed Precipitation | Observed + Designed Precipitation | Observed Precipitation | |

| Max nodal overloading time (min) | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.85 * | |

| Max nodal overloading flow rate (l/s) | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.90 * | |

| Total overloading volume for SWSS (106 l) | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vorobevskii, I.; Al Janabi, F.; Schneebeck, F.; Bellera, J.; Krebs, P. Urban Floods: Linking the Overloading of a Storm Water Sewer System to Precipitation Parameters. Hydrology 2020, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology7020035

Vorobevskii I, Al Janabi F, Schneebeck F, Bellera J, Krebs P. Urban Floods: Linking the Overloading of a Storm Water Sewer System to Precipitation Parameters. Hydrology. 2020; 7(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology7020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleVorobevskii, Ivan, Firas Al Janabi, Fabian Schneebeck, Jose Bellera, and Peter Krebs. 2020. "Urban Floods: Linking the Overloading of a Storm Water Sewer System to Precipitation Parameters" Hydrology 7, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology7020035

APA StyleVorobevskii, I., Al Janabi, F., Schneebeck, F., Bellera, J., & Krebs, P. (2020). Urban Floods: Linking the Overloading of a Storm Water Sewer System to Precipitation Parameters. Hydrology, 7(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology7020035