Numerical Investigation into Effects of Gas Sparger and Horizontal Baffles on Hydrodynamics of Flat Bubble Column

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Equations

2.1. Continuity Equations

2.2. Momentum Equations

Interfacial Closures

3. Numerical Settings, Fluid Domain, and Model Assumptions

Model Assumptions

- Clean surface of bubbles is assumed, without any surfactants or impurities.

- The flow is assumed to exhibit isotropic turbulence.

- Turbulent dispersion force is not considered here.

- Bubble–bubble collisions are assumed to be dominated by turbulence.

- All the bubbles rise at the same velocity, which is the gas velocity.

4. Results and Discussion

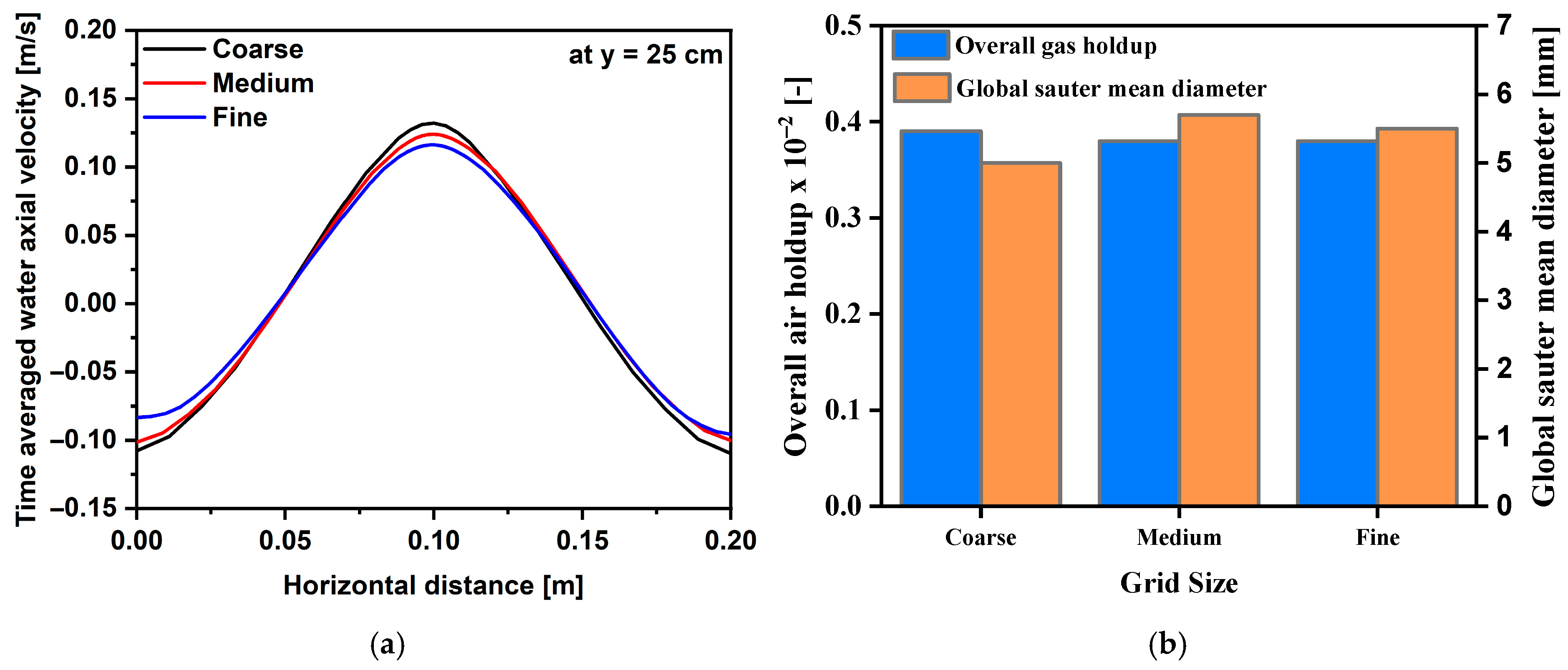

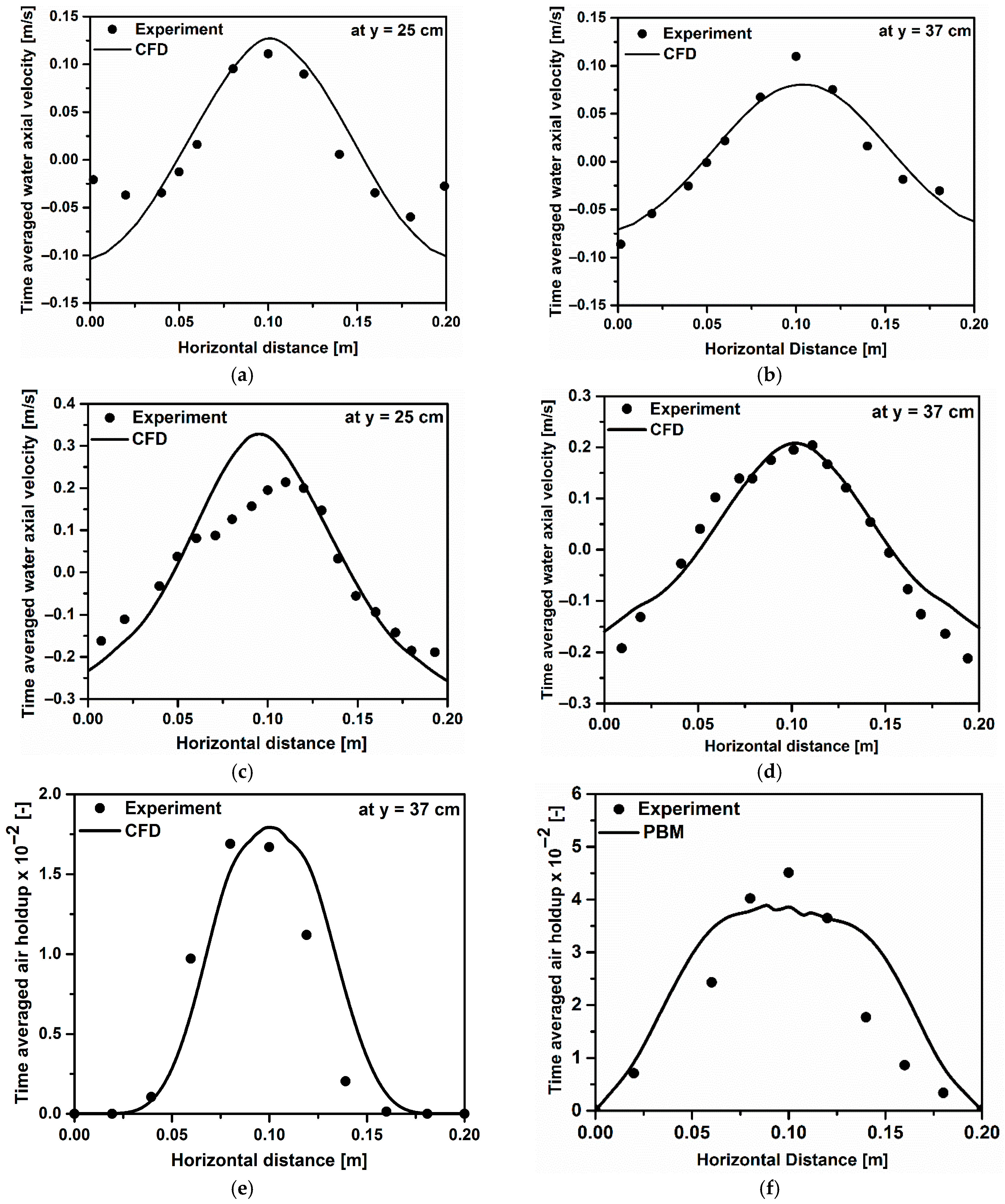

4.1. Grid Sensitivity Analysis and Model Validation

4.2. Simulation Results

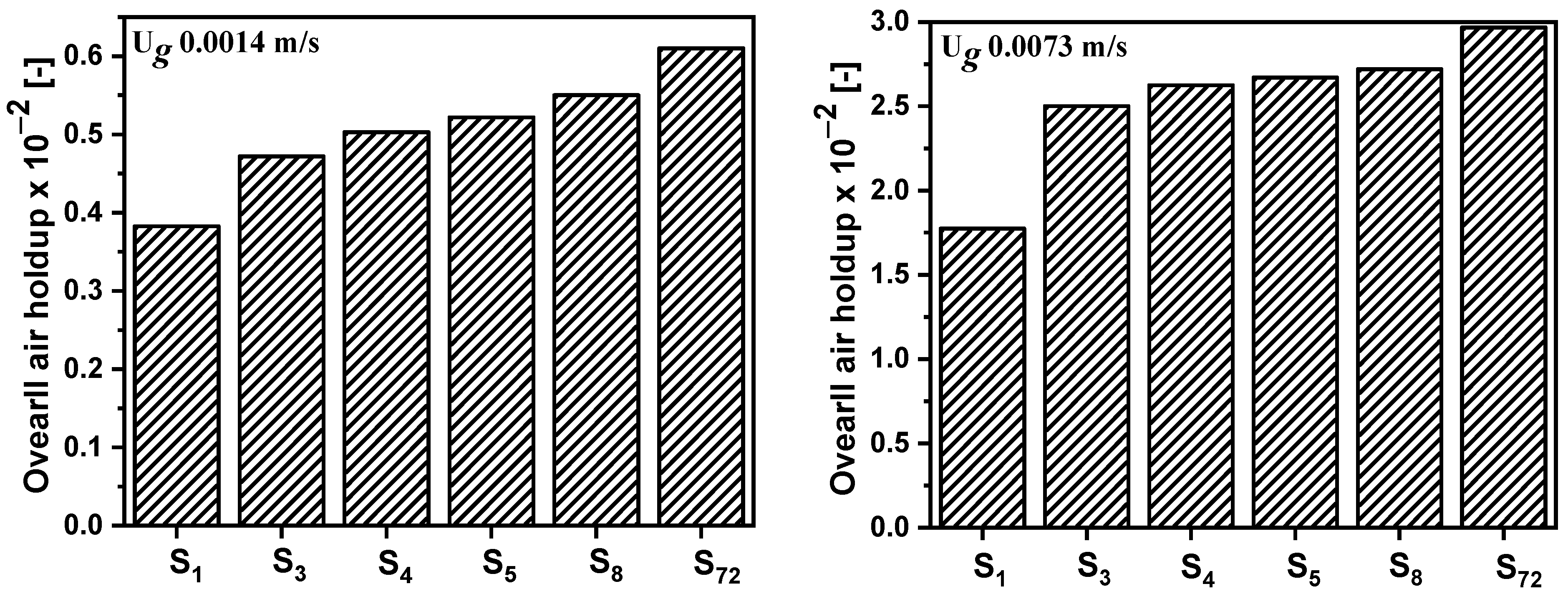

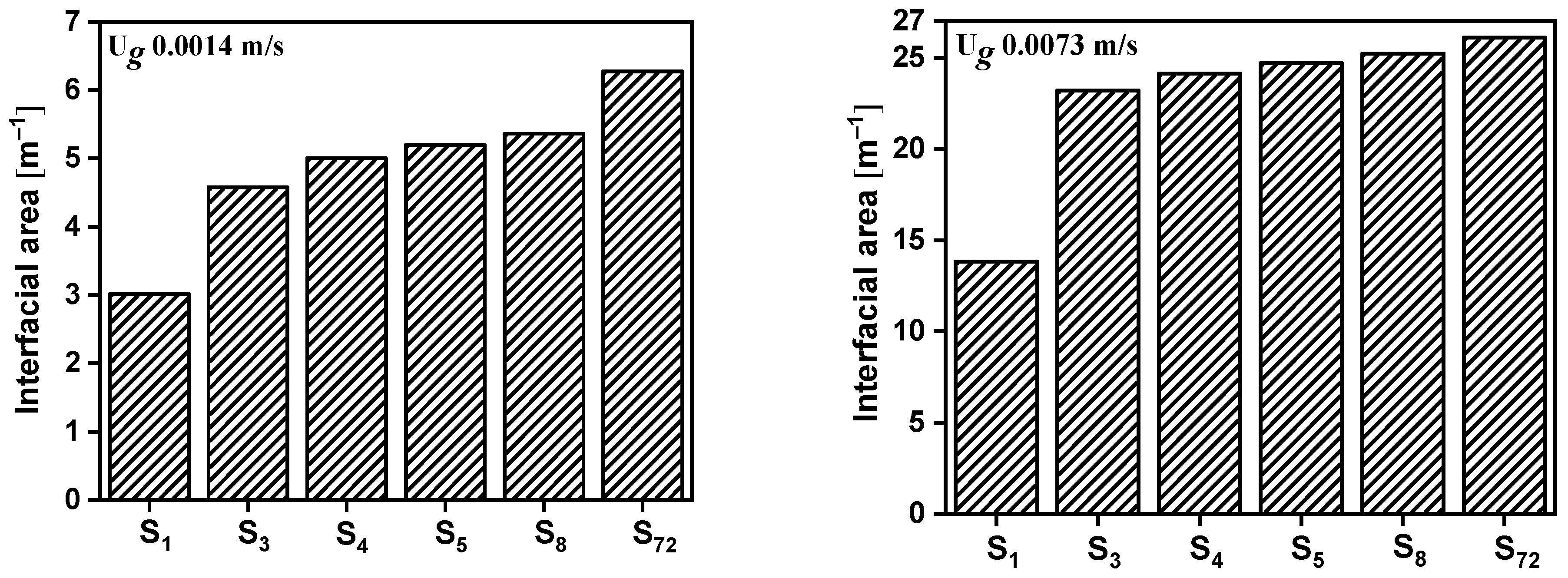

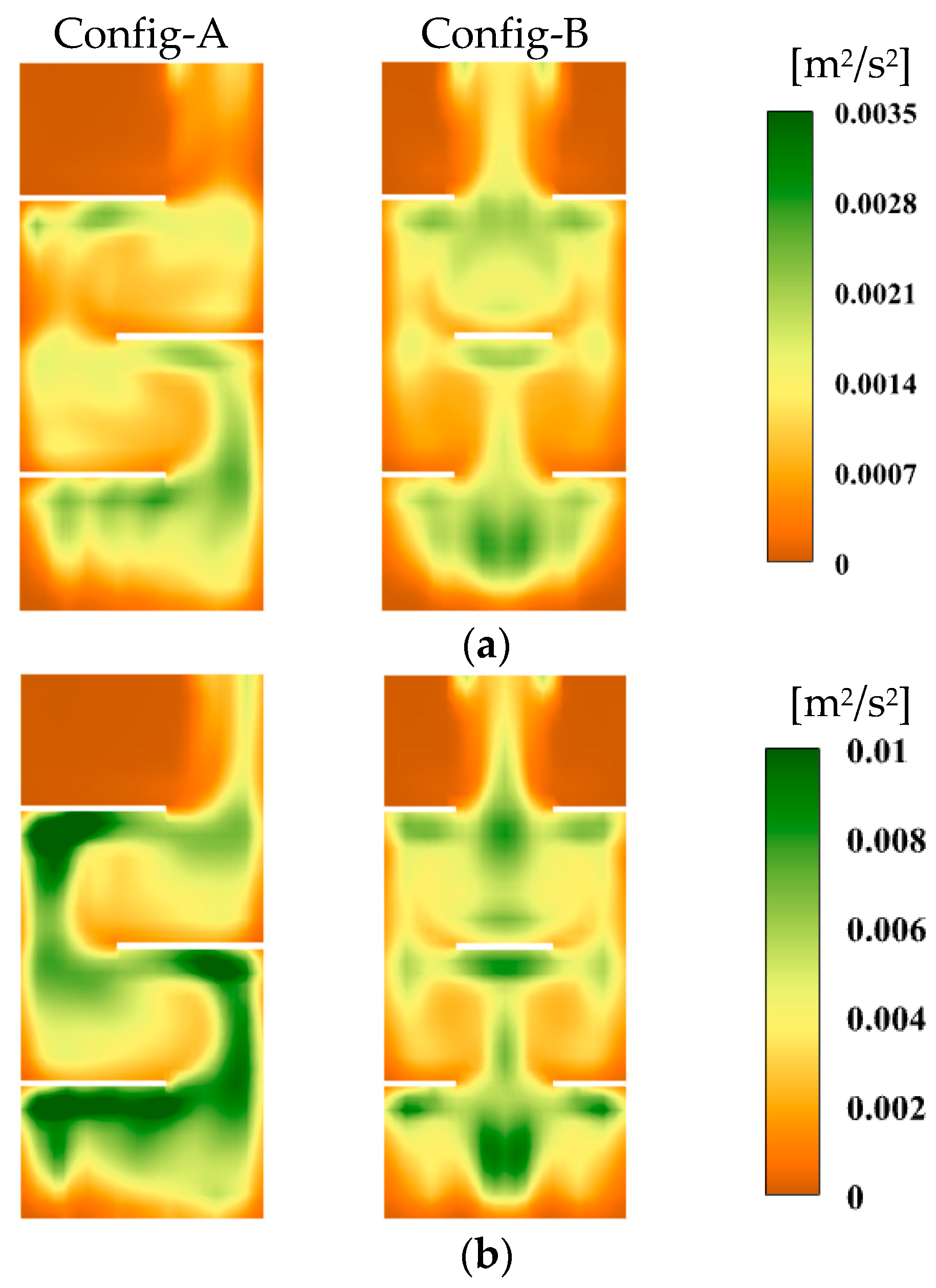

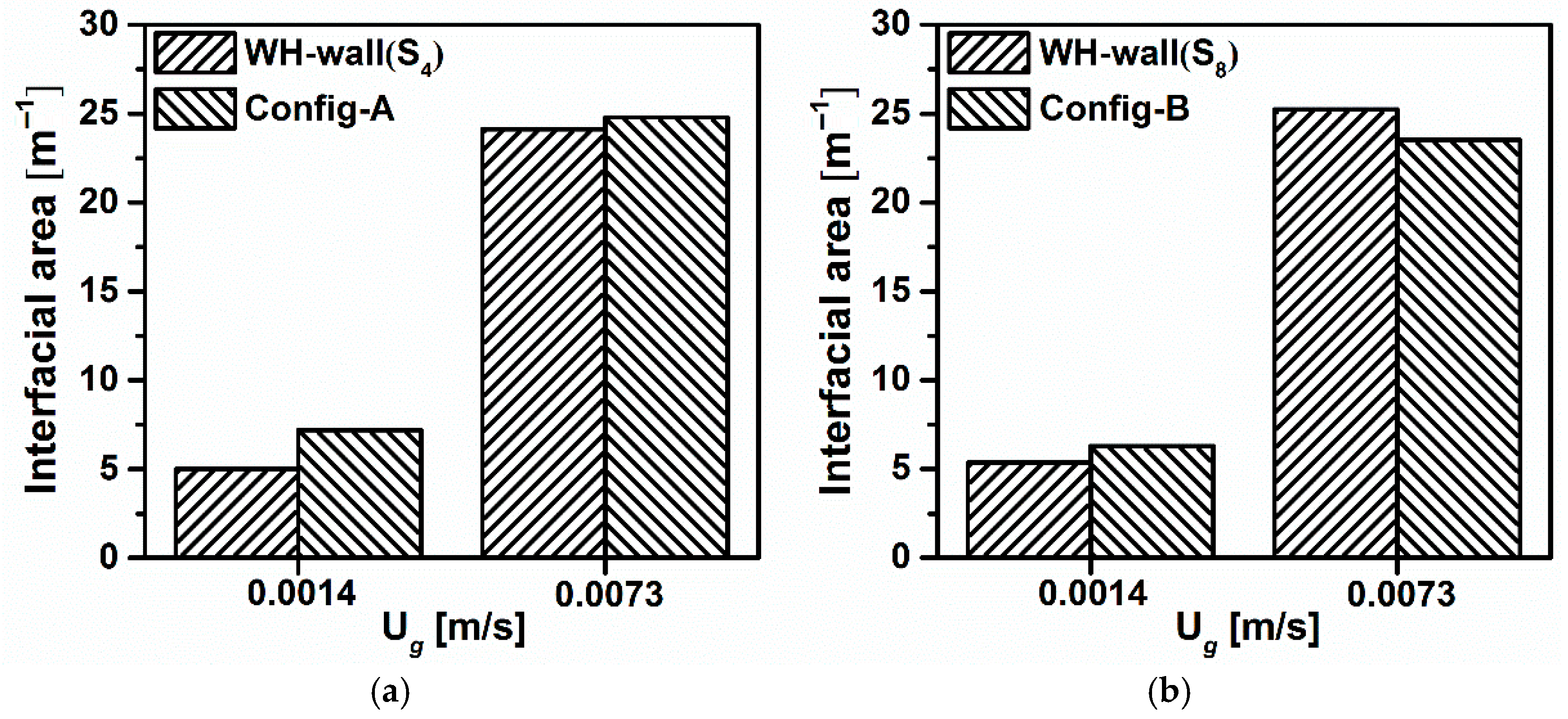

4.2.1. Effect of Gas Sparger

4.2.2. Effect of Horizontal Baffles

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Interfacial area [1/m] | Bulk viscosity [Kg/ms] | ||

| Birth term | Viscosity [Kg/m s] | ||

| Drag coefficient | Dimensionless eddy size | ||

| Lift coefficient | Phase density [Kg/m3] | ||

| Virtual mass coefficient | Surface tension [N/m] | ||

| Wall lubrication coefficient | Collision frequency | ||

| Constant in k-ε turbulence model | |||

| Death term | Subscripts | ||

| Bubble diameter [m] | |||

| Diameter of daughter bubble [m] | b | Bubble | |

| Diameter of parent bubble [m] | i | bin | |

| Sauter mean diameter [m] | phase | ||

| Individual bin size fraction of bin | phase | ||

| Volume fraction of parent bubble in one daughter bubble | |||

| Superscripts | |||

| Total interphase force [N/m3] | |||

| Drag force [N/m3] | br | Breakage | |

| Lift force [N/m3] | c | Coalescence | |

| Virtual mass force [N/m3] | Critical | ||

| Wall lubrication force [N/m3] | Effective | ||

| Gravity [m/s2] | Laminar | ||

| Identity matrix | Turbulent | ||

| Turbulent kinetic energy [m2/s2] | |||

| Mean number of daughter bubbles produced from breakage | |||

| Dimensionless numbers | |||

| Bubble number density [1/m3] | |||

| Coalescence efficiency | Eötvös number, | ||

| Breakup rate [1/m3 s] | Morton number, | ||

| Coalescence rate [m3/s] | Reynold number, | ||

| Source term accounting birth and death terms of bubbles [kg/m3 s] | Weber number, | ||

| Ug | Superficial gas velocity [m/s] | ||

| Terminal velocity [m/s] | Abbreviations | ||

| Characteristic velocity bubble collision [m/s] | |||

| BSD | Bubble size distribution | ||

| Velocity vector [m/s] | PBM | Population balance modeling | |

| SIMPLE | Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations | ||

| Greek Letters | |||

| Void fraction [-] | |||

| Length scale of hitting eddy [m] | |||

| Turbulence dissipation rate [m2/s3] | |||

References

- Chew, K.W.; Chia, S.R.; Show, P.L.; Yap, Y.J.; Ling, T.C.; Chang, J.-S. Effects of water culture medium, cultivation systems and growth modes for microalgae cultivation: A review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 91, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Gómez, A.; López-Rosales, L.; Martínez-Burgos, J.; Molina-Miras, A.; Cerón-García, M.C.; Sánchez-Mirón, A.; García-Camacho, F. Valorisation of seawater desalination brine via cultivation of a halotolerant microalga in bubble column photobioreactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2026, 439, 133261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitankar, V.S.; Joshi, J.B. A Comprehensive One-Dimensional Model for Prediction of Flow Pattern in Bubble Columns. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2002, 80, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, M.; Schlaberg, H.; Wang, M. Effects of sparger geometry on the mechanism of flow pattern transition in a bubble column. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 130, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.E.; Montes, F.J.; Galán, M.A. Influence of Aspect Ratio and Superficial Gas Velocity on the Evolution of Unsteady Flow Structures and Flow Transitions in a Rectangular Two-Dimensional Bubble Column. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 7301–7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhong, W.; Jin, B.; Lu, Y.; He, T. Flow patterns and transitions in a rectangular three-phase bubble column. Powder Technol. 2014, 260, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Sanyal, J.; Duduković, M.P. Numerical simulation of bubble columns flows: Effect of different breakup and coalescence closures. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 1085–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.A.; Ekambara, K.; Joshi, J.B. On the development of flow pattern in a bubble column reactor: Experiments and CFD. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007, 62, 1049–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, N.; Borak, F.; Ulgen, K.O. Bubble column reactors. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 2263–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourtousi, M.; Ganesan, P.; Sandaran, S.C.; Sahu, J.N. Effect of ring sparger diameters on hydrodynamics in bubble column: A numerical investigation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 69, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Cui, Y.; Shi, X.; Su, X.; Gao, J.; Lan, X. Numerical simulation of flow characteristics in microbubble column reactors with two different tubular gas spargers. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2025, 216, 110431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, Y.K.; Pandit, A.B. Effect of internals and sparger design on mixing behavior in sectionalized bubble column. Chem. Eng. J. 2005, 112, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhole, M.R.; Roy, S.; Joshi, J.B. Laser Doppler Anemometer Measurements in Bubble Column: Effect of Sparger. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 9201–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemello, L.; Plais, C.; Augier, F.; Cloupet, A.; Marchisio, D.L. Hydrodynamics and bubble size in bubble columns: Effects of contaminants and spargers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 184, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, D.D.; Wang, C.; Kavanagh, J.M.; Fletcher, D.F.; Barton, G.W. Experimental investigation into the impact of sparger design on bubble columns at high superficial velocities. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 106, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, S.; Bieberle, A.; Caggia, V.; Schubert, M.; Brunazzi, E.; Hampel, U. Axially resolved measurement of axial gas dispersion in bubble columns via gas flow modulation technique. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 517, 163481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaga, D.V.; Pant, H.J.; Dalvi, S.V.; Joshi, J.B.; Roy, S. Investigation of Hydrodynamics in Bubble Column with Internals Using Radioactive Particle Tracking (RPT). Aiche J. 2017, 63, 4881–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.K.; Peng, F.F.; Wolfe, E. CFD simulation of alleviation of fluid back mixing by baffles in bubble column. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaré, J.; Al-Dahhan, M.H. Gas Holdup in Trayed Bubble Column Reactors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 3320–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liang, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Yang, C. Effects of internals on macroscopic fluid dynamics in a bubble column. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 77, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusare, V.H.; Dhiman, M.K.; Kalaga, D.V.; Roy, S.; Joshi, J.B. CFD simulations of a bubble column with and without internals by using OpenFOAM. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 317, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qudoos, A.; Chew, T.L.; Abro, M.; Oh, P.C.; Anbealagan, L.D.; Bustam, M.A.; Ho, C.D.; Jawad, Z.A.; Ng, Q.H. Review on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Modeling and Simulation of CO2 Adsorption. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.F.; McClure, D.D.; Kavanagh, J.M.; Barton, G.W. CFD simulation of industrial bubble columns: Numerical challenges and model validation successes. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 44, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Ziegenhein, T.; Lucas, D.; Fröhlich, J. Large eddy simulations of the gas–liquid flow in a rectangular bubble column. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2016, 299, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Nguyen, A.V.; Afzal, A. Bubble’s rise characteristics in shear-thinning xanthan gum solution: A numerical analysis. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 132, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.-F.; Pan, H.; Su, Y.-H.; Luo, Z.-H. CFD-PBM approach with modified drag model for the gas–liquid flow in a bubble column. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 112, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, C. Simulating the impacts of internals on gas–liquid hydrodynamics of bubble column. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 174, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buwa, V.V.; Ranade, V.V. Mixing in Bubble Column Reactors: Role of Unsteady Flow Structures. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 81, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, J.; Yang, C.; Mao, Z.-S. Simulation of a Bubble Column by Computational Fluid Dynamics and Population Balance Equation Using the Cell Average Method. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2017, 40, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, T. Numerical simulation of volumetric mass transfer coefficients in slurry bubble columns with a CFD-PBM coupled model. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 318, 122153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hinrichsen, O. Study on CFD–PBM turbulence closures based on k–ε and Reynolds stress models for heterogeneous bubble column flows. Comput. Fluids 2014, 105, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.H.; Boulet, M.; Melchiori, T.; Lavoie, J.M. CFD Simulations of an Air-Water Bubble Column: Effect of Luo Coalescence Parameter and Breakup Kernels. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, M.A.; Naser, J.; Brooks, G. Numerical simulation of two-phase flow with bubble break-up and coalescence coupled with population balance modeling. Chem. Eng. Process. 2013, 70, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannari, R.; Kerdouss, F.; Selma, B.; Bannari, A.; Proulx, P. Three-dimensional mathematical modeling of dispersed two-phase flow using class method of population balance in bubble columns. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2008, 32, 3224–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.E.; Iranzo, A.; Cuadra, D.; Barbero, R.; Montes, F.J.; Galán, M.A. Numerical simulation of the gas–liquid flow in a laboratory scale bubble column. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 139, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selma, B.; Bannari, R.; Proulx, P. A full integration of a dispersion and interface closures in the standard k-e model of turbulence. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 5417–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá, J.E.; Hernández, L.; Chiva, S.; Vela, A. Hydrodynamic characterization of a needle sparger rectangular bubble column: Homogeneous flow, static bubble plume and oscillating bubble plume. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007, 62, 6361–6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfleger, D.; Gomes, S.; Gilbert, N.; Wagner, H.G. Hydrodynamic simulations of laboratory scale bubble columns fundamental studies of the Eulerian–Eulerian modelling approach. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1999, 54, 5091–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Pant, H.J.; Roy, S. Liquid flow patterns in rectangular air-water bubble column investigated with Radioactive Particle Tracking. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 96, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, H.; Li, G.; Liu, J. An experimental investigation on bubble-liquid turbulent hydrodynamics in an external-loop airlift bioreactor. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 175, 106290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Roy, S. Euler–Euler simulation of bubbly flow in a rectangular bubble column: Experimental validation with Radioactive Particle Tracking. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 225, 818–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buwa, V.V.; Deo, D.S.; Ranade, V.V. Eulerian–Lagrangian simulations of unsteady gas–liquid flows in bubble columns. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2006, 32, 864–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzpourmachiani, A.; Shams, M.; Shadaram, A.; Azidehak, F. Eulerian–Lagrangian 3-D simulations of unsteady two-phase gas–liquid flow in a rectangular column by considering bubble interactions. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2011, 46, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.D. Governing Equations of Fluid Dynamics. In Computational Fluid Dynamics: An Introduction; Wendt, J.F., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 15–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Yang, C.; Mao, Z.-S. CFD-PBE simulation of premixed continuous precipitation incorporating nucleation, growth and aggregation in a stirred tank with multi-class method. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 68, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Ramkrishna, D. On the solution of population balance equations by discretization Part I. A fixed pivot technique. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1996, 51, 1311–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besagni, G.; Inzoli, F. Prediction of Bubble Size Distributions in Large-Scale Bubble Columns Using a Population Balance Model. Computation 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkrishna, D. Population Balances: Theory and Applications to Particulate Systems in Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H. Coalescence, Breakup and Liquid Circulation in Bubble Column Reactors; Norwegian Institute of Technology: Trondheim, Norway, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lehr, F.; Millies, M.; Mewes, D. Bubble-Size distributions and flow fields in bubble columns. Aiche J. 2002, 48, 2426–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS, I. Ansys Fluent Theory Guide; ANSYS, Inc: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, D.C. Turbulence Modeling for CFD; DCW Industries: La Canada, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Launder, B.E.; Spalding, D.B. Paper 8—The Numerical Computation of Turbulent Flows. In Numerical Prediction of Flow, Heat Transfer, Turbulence and Combustion; Patankar, S.V., Pollard, A., Singhal, A.K., Vanka, S.P., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1983; pp. 96–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y.; Sekoguchi, K. Liquid velocity distribution in two-phase bubble flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1975, 2, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.N.; Mohammed, A.A.; Al-Jubory, F.K.; Barghi, S. CFD assesment of uniform bubbly flow in a bubble column. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 161, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pan, Q.; Chen, J.; Yang, S. CFD-PBM Approach with Different Inlet Locations for the Gas-Liquid Flow in a Laboratory-Scale Bubble Column with Activated Sludge/Water. Computation 2017, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhong, W. CFD simulation of hydrodynamics of gas–liquid–solid three-phase bubble column. Powder Technol. 2015, 286, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oey, R.S.; Mudde, R.F.; van den Akker, H.E.A. Sensitivity study on interfacial closure laws in two-fluid bubbly flow simulations. Aiche J. 2003, 49, 1621–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.K.; d’Ávila, M.A.; Mori, M. Study of the interfacial forces and turbulence models in a bubble column. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2012, 44, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.R. Shapes and Velocities of Single Drops and Bubbles Moving Freely through Immiscible Liquids. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1976, 54, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, M.; Zuber, N. Drag coefficient and relative velocity in bubbly, droplet or particulate flows. AIChE J. 1979, 25, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, A.; Kataoka, I.; Zun, I.; Sakaguchi, T. Drag coefficients of single bubbles under normal and micro gravity conditions. JSME Int. J. Ser. B Fluids Therm. Eng. 1998, 41, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besagni, G.; Varallo, N.; Mereu, R. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modelling of Two-Phase Bubble Columns: A Comprehensive Review. Fluids 2023, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auton, T.R. The lift force on a spherical body in a rotational flow. J. Fluid Mech. 1987, 183, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žun, I. The mechanism of bubble non-homogeneous distribution in two-phase shear flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1990, 118, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ẑun, I. The transverse migration of bubbles influenced by walls in vertical bubbly flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1980, 6, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Gan, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ellahi, M.; Abdeltawab, A.A. Hydrodynamic modeling of ionic liquids and conventional amine solvents in bubble column. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 129, 356–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, D.; Magnaudet, J. The lift force on a spherical bubble in a viscous linear shear flow. J. Fluid Mech. 1998, 368, 81–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, D.A.; Lahey, R.T. The virtual mass and lift force on a sphere in rotating and straining inviscid flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1987, 13, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourtousi, M.; Sahu, J.N.; Ganesan, P. Effect of interfacial forces and turbulence models on predicting flow pattern inside the bubble column. Chem. Eng. Process. 2014, 75, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, S.; Tomiyama, A.; Misaki, S.; Hamada, T. Lateral Migration of Single Bubbles Due to the Presence of Wall. In Proceedings of the ASME 2002 Joint U.S.-European Fluids Engineering Division Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–18 July 2002; pp. 855–860. [Google Scholar]

- Buwa, V.V.; Ranade, V.V. Dynamics of gas–liquid flow in a rectangular bubble column: Experiments and single/multi-group CFD simulations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002, 57, 4715–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.; Van Baten, J.M.; Ellenberger, J.; Higler, A.P.; Taylor, R. CFD Simulations of Sieve Tray Hydrodynamics. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1999, 77, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P.M. Physical Aspects and Scale-Up of High Pressure Bubble Columns. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hughmark, G.A. Holdup and Mass Transfer in Bubble Columns. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 1967, 6, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Sanyal, J.; Dudukovic, M.P. CFD modeling of bubble columns flows: Implementation of population balance. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2004, 59, 5201–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, F.; Seiler, T.; Lau, Y.M.; Weber, M.; Weber, M.; Hampel, U.; Schubert, M. Performance comparison between different sparger plate orifice patterns: Hydrodynamic investigation using ultrafast X-ray tomography. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 316, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Degaleesan, T.E.; Laddha, G.S.; Hoelscher, H.E. Bubble swarm characteristics in bubble columns. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1976, 54, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, K.; Yoshida, F. Bubble Size, Interfacial Area, and Liquid-Phase Mass Transfer Coefficient in Bubble Columns. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 1974, 13, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coarse | Medium | Fine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparger | 6 × 3 | 12 × 5 | 24 × 12 |

| Full domain | 14 × 37 × 6 | 20 × 47 × 6 | 36 × 90 × 8 |

| Total elements | 7326 | 16,544 | 108,000 |

| Inlet | Velocity inlet Ug = 0.0014 m/s and 0.0073 m/s k and ε were set to an initial value of 1 Population balance variables were specified as mono-dispersed BSD |

| Outlet | Pressure outlet (set to atmospheric pressure) |

| Simulation type | Transient |

| Time step size | 0.005 s–0.01 s (fixed) |

| Gravity | −9.81 m/s2 (Y-direction) |

| Wall | Stationary No-slip condition was used for both phases |

| Pressure–velocity coupling | Phase-coupled SIMPLE |

| Discretization Schemes Momentum, volume fraction Turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation rate and air bin | First-order upwind |

| Transient formulation | First-order implicit |

| Under relaxation factors | Default values for each |

| Continuous phase | Water |

| Dispersed phase | Air |

| Bin index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Bubble size (mm) | 1.0 | 1.48 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 3.65 | 5.0 | 6.67 | 9.0 | 12.1 | 16.4 | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abro, M.; Unar, I.N.; Korai, J.; Qudoos, A.; Almani, S.; Laghari, A.Q.; Yu, L.; Jatoi, A.S. Numerical Investigation into Effects of Gas Sparger and Horizontal Baffles on Hydrodynamics of Flat Bubble Column. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060144

Abro M, Unar IN, Korai J, Qudoos A, Almani S, Laghari AQ, Yu L, Jatoi AS. Numerical Investigation into Effects of Gas Sparger and Horizontal Baffles on Hydrodynamics of Flat Bubble Column. ChemEngineering. 2025; 9(6):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060144

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbro, Masroor, Imran Nazir Unar, Junaid Korai, Abdul Qudoos, Sikandar Almani, Abdul Qadeer Laghari, Liang Yu, and Abdul Sattar Jatoi. 2025. "Numerical Investigation into Effects of Gas Sparger and Horizontal Baffles on Hydrodynamics of Flat Bubble Column" ChemEngineering 9, no. 6: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060144

APA StyleAbro, M., Unar, I. N., Korai, J., Qudoos, A., Almani, S., Laghari, A. Q., Yu, L., & Jatoi, A. S. (2025). Numerical Investigation into Effects of Gas Sparger and Horizontal Baffles on Hydrodynamics of Flat Bubble Column. ChemEngineering, 9(6), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060144