1. Introduction

The wetting behavior of droplets on solid surfaces governs diverse phenomena ranging from microfluidic manipulation [

1] and digital microfluidics [

2] to spray coating [

3], self-cleaning surfaces [

4], and biological interfaces [

5]. Classical wetting theory describes droplet equilibrium on homogeneous surfaces through the Young–Laplace equation, which balances capillary pressure with gravitational and external forces. However, real-world applications increasingly involve heterogeneous substrates with spatially varying wettability, where chemical patterning or material discontinuities create regions with distinct contact angles. Understanding droplet equilibrium configurations and dynamics on such surfaces is crucial for designing functional materials with controlled liquid transport and droplet manipulation capabilities [

6,

7].

Heterogeneous wetting has been extensively studied through experimental [

8,

9] and numerical approaches [

10,

11]. Brochard [

12] theoretically analyzed droplet motion induced by chemical or thermal gradients, predicting spontaneous migration toward regions of lower surface energy. Joanny and de Gennes [

13] developed models for contact angle hysteresis on chemically heterogeneous surfaces, revealing the role of surface energy variations in pinning and depinning transitions. Semprebon and Brinkmann [

14] investigated the onset of motion for sliding drops on surfaces with contact angle hysteresis, establishing critical conditions for droplet mobility and demonstrating that drops on heterogeneous surfaces can exhibit continuous migration when equilibrium configurations become inaccessible. More recently, Devic et al. [

15] investigated equilibrium shapes of droplets on tilted substrates with chemical steps using Surface Evolver, identifying critical volumes beyond which stable equilibrium becomes inaccessible. Numerical simulations based on phase-field methods [

16] and volume-of-fluid techniques [

17] have also provided insights into dynamic wetting on complex surfaces. Lubarda et al. [

18] developed analytical models for equilibrium droplet shapes on curved substrates using ellipsoidal cap approximations, demonstrating how substrate curvature modifies the classical Young–Laplace analysis and affects contact line positioning.

Recent advances have highlighted the importance of chemical steps—elementary patterns in chemically heterogeneous substrates featuring two regions of different wettability separated by a sharp border [

19]. Long and Gao [

19] systematically investigated droplet motion driven by chemical steps within the framework of lubrication theory, identifying two distinct stages: a migration stage where the droplet traverses both regions, and an asymmetric spreading stage where the droplet spreads on the hydrophilic region while being constrained by the border. Their matched asymptotic analysis for 2D droplets revealed that steady translational motion with constant speed can occur during migration, while a boundary layer exists near pinned contact lines during asymmetric spreading. For 3D droplets, their numerical simulations demonstrated that lateral flow significantly affects evolution, leading to non-monotonic variations in droplet length and width. These findings provide fundamental insights into droplet behavior on stepped wettability patterns, which are ubiquitous in applications ranging from digital microfluidics to water harvesting systems.

The control of droplet motion through wettability modulation has emerged as a critical capability for numerous technologies. Tenjimbayashi and Manabe [

6] provided a comprehensive review categorizing droplet manipulation strategies into three main approaches: (i) application of driving force to droplets on non-sticking surfaces such as superhydrophobic or liquid-infused surfaces, (ii) formation of gradient surface chemistry or structure inspired by natural systems like spider silk and cactus spines [

20,

21], and (iii) formation of anisotropic surface chemistry or structure exemplified by directional wetting patterns. These strategies have enabled diverse applications spanning microfluidics [

22], heat and mass transfer [

23,

24], bioanalysis [

25], and self-cleaning surfaces [

26], among many others detailed in recent reviews [

6,

7]. Curvature-induced pressure differences have been exploited for controlled droplet manipulation in microfluidic devices, such as selective droplet splitting in microvalve networks where differential curvature across geometric constrictions enables size-based sorting [

27]. Understanding the fundamental principles underlying these strategies is essential for rational design of functional surfaces with tailored droplet manipulation capabilities.

Despite these advances, analytical frameworks for predicting equilibrium configurations on heterogeneous surfaces remain limited, particularly for asymmetric systems where the droplet straddles a wetting boundary. Several recent studies have made significant progress in understanding droplet behavior on chemical steps and patterned surfaces, but important gaps remain. Devic et al. [

15] used Surface Evolver to systematically investigate equilibrium drop shapes on tilted substrates with chemical steps, identifying critical volumes beyond which stable equilibrium becomes inaccessible due to gravitational drainage. Their numerical approach provides valuable phase diagrams mapping stable configurations in volume-tilt angle space, but does not yield analytical criteria for contact line positioning or address the horizontal substrate limit where gravitational tilting vanishes. Wu et al. [

28] explored droplets on surfaces with periodic wettability patterns (stripes, checkerboards) and demonstrated that multiple metastable configurations can coexist due to contact line pinning and energy barriers, highlighting the complexity of real systems with contact angle hysteresis. Their finite element simulations reveal rich morphological diversity but require computationally intensive energy minimization for each configuration without providing closed-form predictions.

Theoretical approaches based on the Young–Laplace equation have traditionally relied on full numerical optimization of the coupled differential–algebraic system, which can be computationally expensive and sensitive to initial conditions. The challenge lies in simultaneously satisfying the Young–Laplace equation governing interface curvature, Young’s law at each contact line, and the global volume constraint, while determining the unknown equilibrium position relative to the heterogeneous boundary. Most existing approaches require iterative solution of 4–5 coupled nonlinear equations at each parameter combination, making parametric studies and inverse design problems computationally prohibitive. Furthermore, the interplay between static equilibrium configurations and dynamic migration processes on chemical steps requires careful consideration of contact line dynamics, including pinning phenomena and contact angle hysteresis [

29,

30].

Table 1 summarizes the scope, methodology, and key findings of representative studies on droplets at heterogeneous surfaces, highlighting how the present work complements and extends existing approaches.

The present work addresses these gaps through a hybrid analytical-numerical framework that combines rigorous energy minimization principles with efficient parametric methods. Our key innovation is deriving an explicit spreading condition from Lagrange multiplier analysis that decouples the equilibrium position determination from the shape computation, dramatically reducing computational cost while providing physical insight into the force balance. Unlike Devic et al.’s phase diagrams [

15] that require separate Surface Evolver runs for each configuration, our simplified spreading condition

provides immediate predictions for contact line partitioning given only the contact angles. Unlike Wu et al.’s metastability analysis that focuses on hysteresis and pinning barriers [

28], our framework identifies the global energy minimum for systems with prescribed equilibrium contact angles, establishing the ultimate equilibrium state toward which dynamic systems relax. Compared to Long & Gao’s lubrication theory for dynamic migration [

19], our static analysis reveals the fundamental equilibrium criterion that governs the terminal configuration after migration ceases, valid for arbitrary Bond numbers without small-angle approximations.

In this work, we present a systematic numerical framework for computing asymmetric droplet shapes on heterogeneous surfaces with a wetting boundary separating two regions of distinct contact angles. Our approach combines rigorous energy minimization principles with efficient parametric numerical methods to achieve accurate solutions across diverse contact angle configurations and gravitational regimes characterized by the Bond number. The key innovation is a two-stage computational strategy: first, we compute a reference droplet shape by solving the parametric Young–Laplace equations using Newton–Raphson iteration; second, we apply an algebraic spreading condition derived from energy minimization to determine the equilibrium position through simple translation. This decoupling dramatically reduces computational cost compared to fully coupled approaches while maintaining high accuracy.

We derive the spreading condition from first principles through Lagrange multiplier analysis of the constrained Gibbs free energy functional. The resulting equilibrium criterion relates the contact line position ratio to the spreading function ratio , where encodes the unbalanced Young stress at each contact line. Under appropriate approximations valid for small to moderate Bond numbers, this condition reduces to an explicit algebraic relation that eliminates the need for iterative root-finding. The parametric formulation using tangent angle as the independent variable naturally handles vertical tangent singularities near contact lines, ensuring robust numerical integration.

We validate the framework through systematic parameter studies examining contact angle asymmetry in both hydrophilic and hydrophobic regimes, and Bond number variations spanning capillary-dominated to gravity-influenced regimes. The results reveal fundamental behaviors including the counterintuitive spreading of hydrophobic droplets toward regions with larger contact angles, the invariance of horizontal partitioning under gravitational effects, and the strong nonlinear sensitivity of asymmetry to contact angles near

. These findings advance our understanding of wetting on heterogeneous surfaces and provide quantitative design criteria for applications in microfluidics, surface patterning, and droplet-based technologies, complementing recent advances in dynamic droplet manipulation [

6,

19].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 formulates the problem, derives the governing Young–Laplace equation, and develops the spreading condition from energy minimization principles.

Section 3 presents the two-stage numerical method including parametric Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) formulation, Newton–Raphson iteration, and algebraic spreading condition satisfaction.

Section 4 presents comprehensive results across parameter space, and

Section 5 concludes with implications and future directions.

3. Variational Analysis for Spreading Condition

The equilibrium configuration must satisfy the spreading condition derived from energy minimization. We derive this condition through systematic variational analysis starting from the Gibbs free energy functional with volume constraint.

At each contact line, the equilibrium condition is governed by Young’s equation. At the left and right contact points, we have

The total Gibbs free energy change from a reference state, where the entire surface is a solid–gas interface, consists of four contributions. The first contribution comes from the liquid–gas interface energy

where

represents the arc length of the liquid–gas interface. The second contribution arises from the solid-liquid interface on the left side

While the third contribution comes from the right contact area

and the fourth contribution is the gravitational potential energy

Combining all four components and introducing dimensionless variables using a characteristic length scale

R and the Bond number

, the dimensionless energy functional becomes

subject to the volume constraint

We decompose the total volume at the heterogeneity boundary

into left and right contributions

with the constraint

.

We now examine how the energy changes with respect to variations in the contact positions. At the contact point

, the arc length element satisfies

where we have used the contact angle condition

. When

changes, the arc length contribution gives

and the surface energy contribution varies as

where we have used

for

. The gravitational contribution requires more careful analysis. When

changes, both the integration limits and the shape

change. The total derivative is

The first term represents the direct boundary contribution, which vanishes since

. However, the second term represents the shape variation and does not vanish. Combining all three contributions, the total energy derivatives for the left and right contact position are

To find the equilibrium configuration, we employ the method of Lagrange multipliers to enforce the volume constraint. Since the droplet shape in each region (left and right) must satisfy different Young–Laplace equations with different pressure constants and , we introduce separate Lagrange multipliers and for the left and right regions, respectively.

The equilibrium conditions require

Substituting the expressions for energy and volume derivatives, we obtain the equilibrium conditions

The physical interpretation of these Lagrange multipliers becomes clear when we recognize that they represent the pressure constants in the Young–Laplace equation for each region. Specifically, and by examining the equilibrium conditions in the context of the governing differential equations.

Since

is constant, the total differential must vanish

which gives

Under the volume constraint

, the total differential of

with respect to

while maintaining constant volume is

Multiplying Equation (

14) by

, adding to Equation (

13), and applying Equation (

15), we obtain the general spreading condition

This result expresses the equilibrium condition with three distinct contributions. The left-hand side represents the gravitational contribution under constrained contact line motion (total derivative with volume constraint). On the right-hand side, the first two terms represent the capillary forces from both contact lines weighted by their geometric ratio, while the third term represents the contribution from the pressure difference between the left and right regions, which arises from the curvature discontinuity.

We now integrate the spreading condition Equation (

16) with respect to

from 0 to

to obtain an algebraic form. The first term in the right-hand side gives

. The second term, using the chain rule

, becomes

, where

represents the relationship between

and

under the volume constraint. For the third term, since the total volume is constrained to be constant

, the curvature difference term vanishes because the volume remains at

throughout the integration path, despite

for asymmetric droplets. Combining all terms, the general spreading condition can be rewritten as

where

is the spreading function. The double integral in the left-hand side represents the accumulated change in the gravitational energy functional as the contact line position varies from 0 to

while maintaining constant volume.

For the case of horizontal translation where the droplet shape does not change with position, we have

throughout the domain. This causes the left-hand side to vanish. Therefore, we obtain the simplified spreading condition

The integrated spreading condition Equation (

18) is a remarkable result that requires only the horizontal translation assumption (

) and is valid for arbitrary Bond numbers without invoking geometric self-similarity. The spreading function

represents the effective spreading force per unit length at each contact line arising from the unbalanced Young stress. The equilibrium configuration requires that the product of this force and the contact line position be equal on both sides, establishing a fundamental balance between the spreading tendencies at the left and right contact lines and together with the constraint on total droplet width

where

is the width of the reference droplet, we obtain a closed algebraic system that can be solved explicitly for the equilibrium contact positions. The simplified spreading condition Equation (

18) states that at equilibrium, the ratio of contact positions equals the ratio of spreading functions. This can be interpreted as a balance of spreading intensities where the tendency to spread at the left contact line exactly balances the tendency to spread at the right contact line, with the contact positions adjusting to maintain this balance.

4. Numerical Implementation

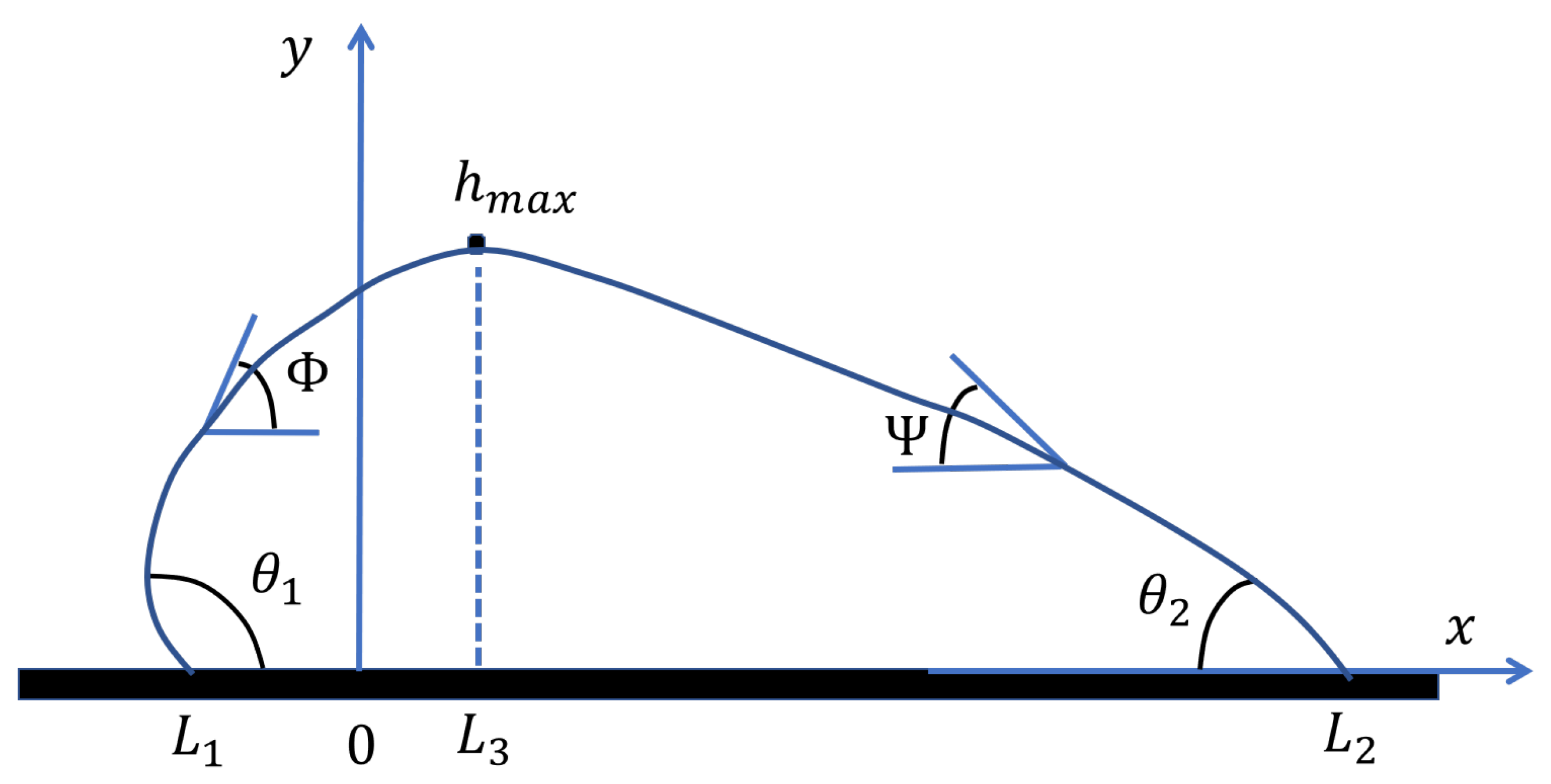

The numerical solution strategy consists of two stages. In the first stage, we compute a reference droplet shape with the maximum height positioned at without loss of generality. This yields a droplet shape characterized by three unknown parameters: , , and . In the second stage, we apply the spreading condition to determine the correct heterogeneity boundary position through algebraic calculation, effectively translating the reference shape horizontally to satisfy equilibrium.

To solve the Young–Laplace equation numerically, we employ a parametric formulation that uses the tangent angle as the independent variable rather than the horizontal coordinate x. This approach naturally handles the vertical tangent singularities that occur near the contact lines and provides a robust computational framework. For the left side, we introduce the angle variable defined such that . For the right side, we use with . At the maximum height where , both angles vanish since the slope is zero.

The detailed derivation of the parametric formulation for capillary surface problems can be found in Lee [

31].

Starting from the relation

for the left side, we obtain

. Using the trigonometric identity

, we find

. Substituting these into the Young–Laplace equation Equation (

6) and rearranging yields the parametric ordinary differential equations

which we integrate from

at the maximum to

at the left contact point with initial conditions

and

.

Similarly, for the right side starting from

, we obtain

which we integrate from

to

with the same initial conditions at the maximum height.

The problem now reduces to finding three unknown variables that satisfy three constraint equations. The unknowns are the maximum height , the left pressure constant , and the right pressure constant . These parameters completely characterize the reference droplet shape positioned at .

The three constraint equations ensure that the solution satisfies all physical requirements. The first constraint requires that the left side profile reaches zero height at the left contact angle, which gives

where

denotes the height computed by integrating the left-side ODEs. The second constraint requires that the right side profile reaches zero height at the right contact angle, giving

. The third constraint enforces the volume condition

, where the regional volumes are computed by integrating

along with the parametric ODEs during the integration process.

We solve this system of nonlinear equations using the Newton–Raphson method. At each iteration

k, we update the solution vector according to

where

is the

Jacobian matrix containing the partial derivatives of the constraint functions with respect to the unknown variables. The Jacobian matrix elements are computed using finite difference approximations with perturbation parameters

and

typically set to

.

The initial guess for the iterative procedure significantly affects convergence. For the symmetric case (), analytical solutions for spherical cap droplets provide excellent initial estimates through , , where for zero Bond number. For asymmetric cases, we employ a continuation method starting from the symmetric solution and gradually varying one contact angle while using the previous solution as the initial guess for the next parameter value. For non-zero Bond numbers, we use the solution as the starting point and incrementally increase the Bond number. The iteration continues until the constraint functions satisfy where is the prescribed tolerance to ensure high accuracy in computing the droplet profile and volume. Convergence is typically achieved within 5-10 iterations for well-chosen initial guesses. The parametric ODE integration employs MATLAB’s (R2022b) ode45 function based on the Dormand–Prince method with adaptive step size control. The integration proceeds from the maximum height at (or ) where the denominator (or ) is well-behaved, avoiding potential singularities near the contact lines.

Once converged, the reference solution provides the complete droplet profile positioned at , along with the contact positions and for this reference configuration. The total droplet width is , which will be preserved under horizontal translation.

The reference droplet shape computed in the first stage satisfies the Young–Laplace equation, the contact angle conditions, and the volume constraint. However, the contact line positions

and

generally do not satisfy the spreading condition Equation (

18). To find the equilibrium configuration, we must determine the correct contact positions

and

that satisfy the spreading condition. The key insight is that horizontal translation of the droplet along the substrate preserves the droplet shape

, the total volume

, and the total width

. The translation only changes the positions of the contact lines relative to the heterogeneity boundary at

. Therefore, we seek new contact positions

and

satisfying two conditions of Equations (

18) and (

19). These are a simple algebraic system of two equations in two unknowns for

and

. Therefore, the explicit solutions are

where

is the ratio of spreading functions.

The horizontal shift required to move from the reference configuration to the equilibrium configuration is

Finally, the equilibrium droplet profile is then obtained by applying this horitzontal translation

where

s parameterizes points along the droplet surface. The maximum height position in the equilibrium configuration is located at

, and the heterogeneity boundary is at

. The horizontal translation approximation assumes that the droplet shape does not change as it translates along the substrate, so

. This is exactly satisfied when we first compute the reference shape independently and then translate it horizontally.

This algebraic approach is computationally trivial compared to iterative root-finding methods. Once the reference shape is computed in the first stage, the equilibrium configuration is determined by simple arithmetic operations. The volumes and on each side of the heterogeneity boundary can be computed by numerical integration (e.g., trapezoidal rule) of the translated profile, providing verification that the spreading condition is satisfied.

The two-stage solution strategy offers several computational advantages. By decoupling the shape computation from the spreading condition satisfaction, we reduce the dimensionality of the nonlinear system in the first stage from potentially four or five unknowns to only three, making the Newton–Raphson iteration more robust and faster to converge. In the second stage, the problem reduces to explicit algebraic formulas, eliminating the need for iterative root-finding entirely.

5. Results

We now present numerical solutions demonstrating droplet equilibrium configurations on heterogeneous surfaces across a wide parameter space. The results are organized to systematically examine the influence of contact angle asymmetry and gravitational effects: we first analyze the asymmetry parameter

in contact angle space (

Figure 2), then explore droplet shapes for hydrophilic surfaces (

Figure 3), hydrophobic surfaces (

Figure 4), and finally investigate Bond number variations (

Figure 5).

Figure 2 presents contour lines of

as a function of normalized contact angles

and

, where

from Equation (

18) is defined as

where the parameter

characterizes the asymmetry in droplet geometry on heterogeneous surfaces, with

and

representing the contact angles at opposite sides of the droplet. The diagonal line (solid line) represents

, corresponding to

, which occurs when

. This represents a symmetric droplet configuration on a homogeneous surface. Above this diagonal (

),

indicates physically realizable asymmetric droplet shapes. The dashed, dash-dot, and dotted lines represent

, and 3, corresponding to

, and 1000, respectively. These contours show increasing levels of asymmetry as

becomes significantly larger than

. The contours cluster near

, indicating that the asymmetry parameter

becomes extremely sensitive to changes in contact angle in this region due to the singularity of

at

. The region below the diagonal (

) corresponds to

, or equivalently,

. While mathematically valid, these negative logarithm values represent less asymmetric droplet configurations where

. Since the definition of

is not symmetric with respect to interchange of

and

, the region with

is simply the mirror image of the

region.

Importantly, the condition where one contact angle is greater than (hydrophobic) while the other is less than (hydrophilic) leads to , which is physically meaningless. In such extreme wettability gradient conditions, a static equilibrium droplet configuration cannot exist.

This explains the continuous droplet migration observed in dynamic studies of Semprebon & Brinkmann [

14] for similar contact angle combinations on homogeneous surfaces with hysteresis. The ’steady moving state’ in such systems is fundamentally a non-equilibrium phenomenon driven by the impossibility of satisfying our spreading condition. The droplet would spontaneously migrate toward the more hydrophilic region due to the imbalance in interfacial forces. Therefore, only the region where both contact angles are on the same side of

(both less than or both greater than

) represents physically realizable droplet states. This contour map is particularly useful for predicting droplet behavior on surfaces with controlled wettability gradients, which has applications in microfluidics, self-cleaning surfaces, and droplet manipulation technologies.

Similarly, the counterintuitive spreading of hydrophobic droplets toward higher contact angle regions (

Figure 4) agrees qualitatively with the observations of Moumen et al. [

9] on wettability gradient surfaces.

We first verify that our numerical solutions satisfy fundamental physical principles. For symmetric cases (

), our method correctly produces symmertic droplet shapes with

and

. The volume constraint is satisfied to within the prescribed tolerance for all cases in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

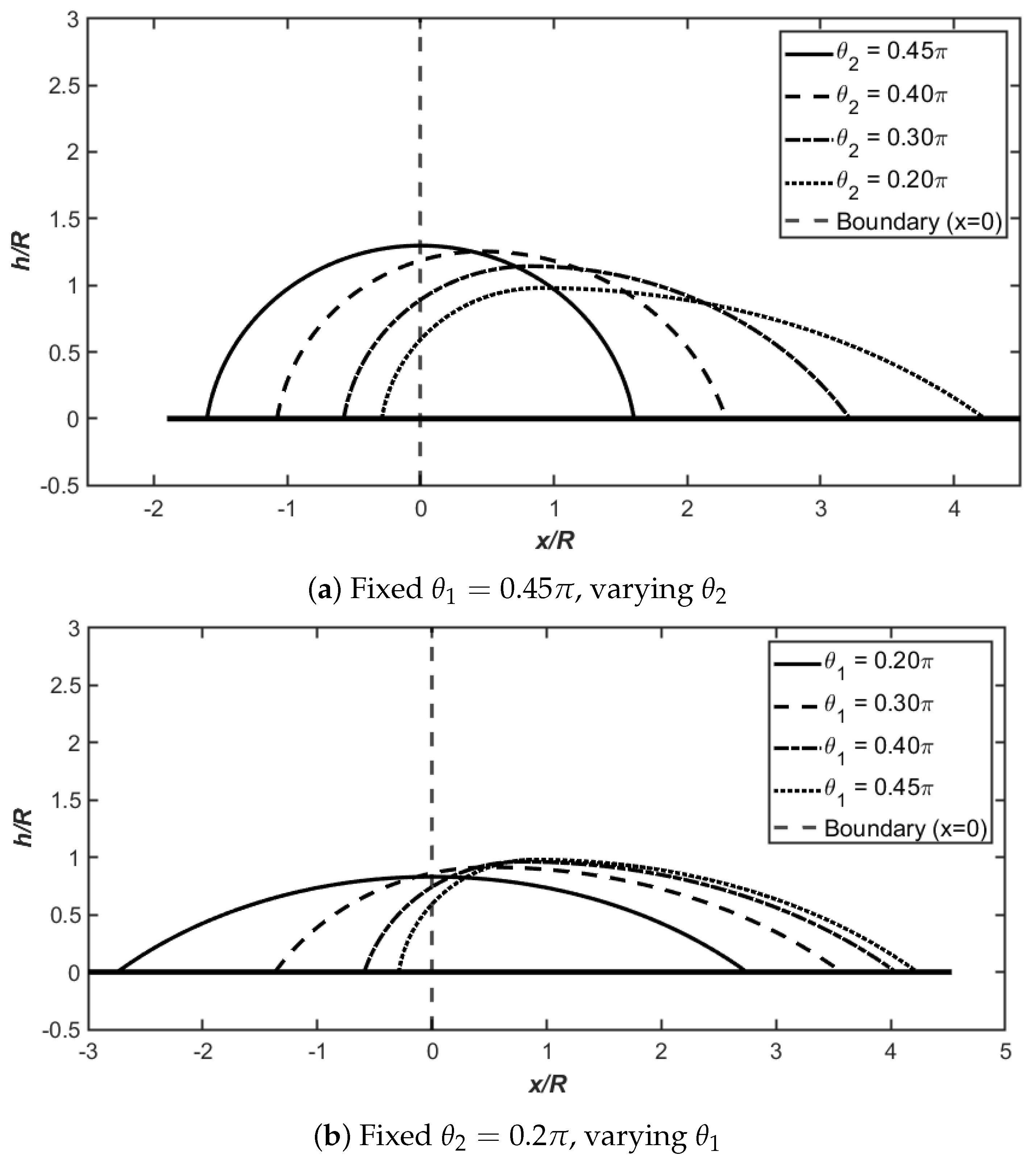

Figure 3 illustrates the variation of droplet shapes at Bond number

for different contact angle configurations, with corresponding data provided in

Table 3. The vertical line in (a) and (b) indicates the heterogeneous wetting boundary at

.

Figure 3a examines the case where the left contact angle is fixed at

while the right contact angle

decreases from

to

. As

decreases, the droplet progressively shifts toward the right side (the region with smaller contact angle) in accordance with the spreading condition. This asymmetric configuration demonstrates the fundamental principle that droplets tend to spread preferentially toward regions with better wettability. When both contact angles are equal (

), the droplet exhibits a symmetric shape with zero curvature difference (

) and a balanced length ratio (

). As the contact angle difference increases, several key trends emerge from the data: the curvature difference

increases significantly from 0 to 0.66591, the length ratio

increases dramatically from 1 to 14.60252 (reflected in the asymmetry parameter

), and the maximum height

decreases from 1.29742 to 0.97999. These changes indicate that greater wettability contrast leads to more pronounced asymmetry and flattening of the droplet profile.

Figure 3b presents the complementary scenario where the right contact angle is fixed at

while the left contact angle

decreases from

toward

. As

approaches

, the droplet transitions from an asymmetric to a symmetric configuration. The curvature difference

decreases progressively as the contact angles converge, and the length ratio

approaches unity, indicating restoration of geometric symmetry. Notably, the maximum height

in the symmetric case (

) is substantially lower at 0.83096 compared to 1.29742 when both angles equal

. This demonstrates that droplets with smaller equilibrium contact angles (more hydrophilic surfaces) naturally adopt flatter profiles due to enhanced spreading.

Together, these two panels comprehensively demonstrate how the spreading condition governs the equilibrium position and shape of droplets on heterogeneous surfaces, highlighting the interplay between contact angle asymmetry, curvature distribution, geometric proportions, and overall droplet morphology.

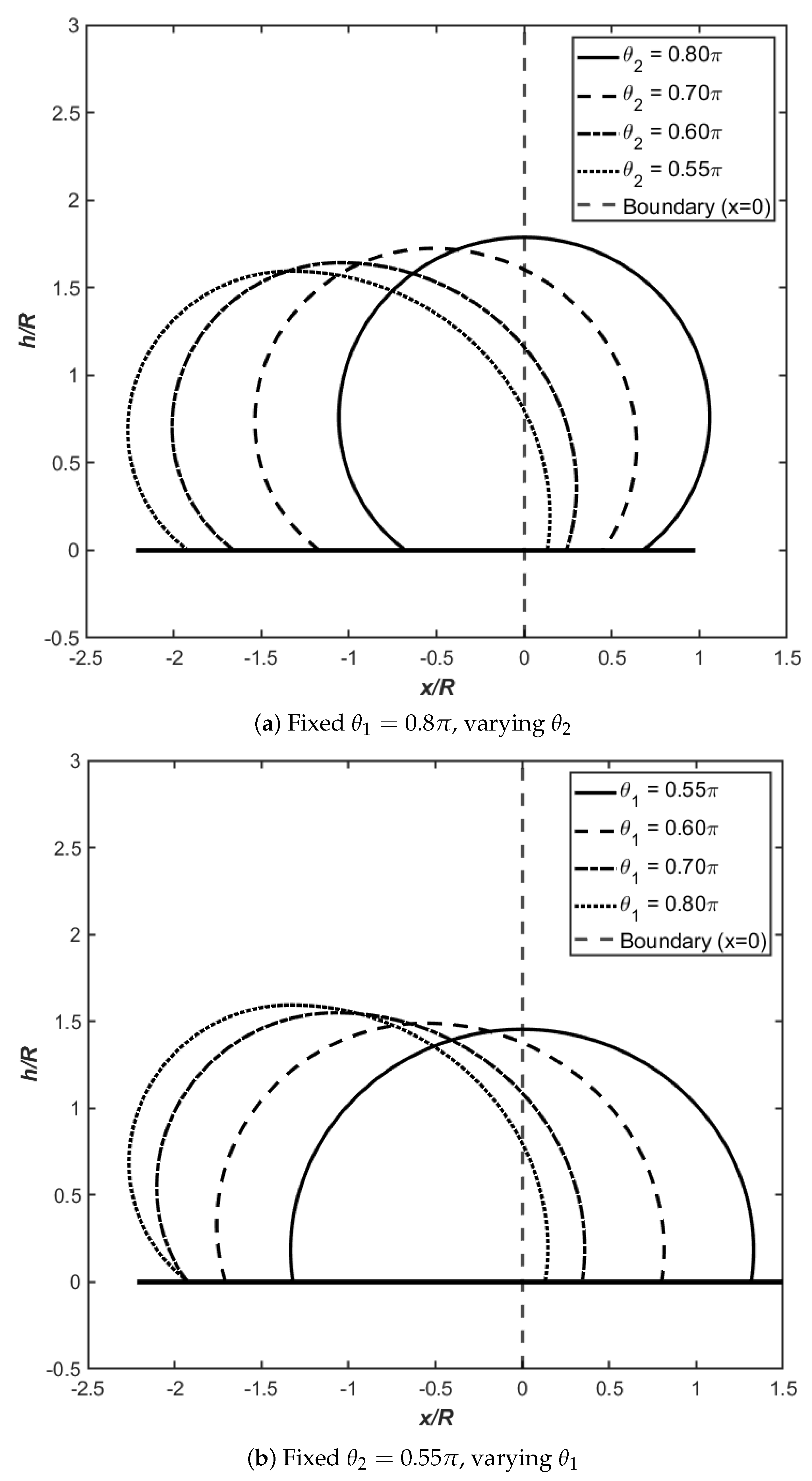

Figure 4 demonstrates droplet behavior on hydrophobic heterogeneous surfaces at

, where both contact angles exceed

. The numerical data for this configuration are tabulated in

Table 4. The heterogeneous boundary at

is marked by the vertical line in both panels. Unlike hydrophilic surfaces where droplets spread extensively, hydrophobic surfaces resist wetting, resulting in characteristically tall and compact droplet profiles.

In

Figure 4a, we investigate droplets with

on the left side while systematically varying

from

down to

on the right. The physical behavior contrasts markedly with hydrophilic cases: as

becomes smaller (less hydrophobic), the droplet redistributes its volume preferentially to the left side where the contact angle remains large.

Table 4 reveals a striking asymmetry evolution: starting from the symmetric baseline (

) where

and

, the length ratio plummets to

when

, while the curvature difference rises to

. This nearly fifteenfold reduction in the length ratio (equivalently,

) indicates extreme geometric asymmetry where the droplet base extends far more on the hydrophobic left side. The maximum height decreases modestly from

to

, suggesting that while the droplet becomes more asymmetric, it maintains relatively tall profiles characteristic of hydrophobic wetting.

Figure 4b explores the inverse scenario: fixing

on the right while increasing

from

to

. Beginning from a symmetric configuration at

where

, the droplet responds to increasing left-side hydrophobicity by developing pronounced asymmetry toward the left. The data show that

rises to

as

reaches

, reflecting the tendency of larger contact angles to elevate droplet height by restricting lateral spreading. The length ratio decreases systematically, and the curvature difference

grows from zero to

. Comparing the two symmetric limits reveals an important scaling:

at

versus

at

, demonstrating that droplet height scales strongly with the degree of hydrophobicity.

The key physical insight from

Figure 4 is the reversal of spreading directionality on hydrophobic surfaces: droplets preferentially occupy regions with larger contact angles (greater hydrophobicity) rather than smaller ones. This counterintuitive behavior arises because on hydrophobic surfaces, the spreading function

dictates that equilibrium requires the droplet to extend more on the side where wetting is most unfavorable. The resulting droplet morphologies are tall, compact, and strongly asymmetric, with curvature discontinuities at the heterogeneous boundary that become more pronounced as contact angle disparity increases.

Figure 5 examines the influence of Bond number on asymmetric droplet morphology while maintaining fixed contact angles at

and

. The Bond number varies from

(capillary-dominated regime) to

(significant gravitational influence), with quantitative data summarized in

Table 5. The vertical dashed line at

marks the heterogeneous boundary position in this coordinate system.

Figure 5 clearly demonstrates the progressive flattening of droplet profiles as gravitational effects become increasingly important. At the smallest Bond number

, surface tension dominates the force balance, producing a tall, nearly spherical cap with maximum height

. This configuration closely resembles the capillary-length-limited ideal where gravity plays a negligible role. As the Bond number increases to

, gravitational deformation becomes noticeable, reducing the maximum height to

. The droplet begins to deviate from the spherical profile, with the apex slightly depressed and the base correspondingly widened. Further increasing the Bond number to

and

amplifies this trend dramatically: the maximum heights decrease to

and

, respectively. The droplet progressively adopts a puddle-like geometry where lateral extent dominates over vertical height, characteristic of gravity-dominated sessile drops.

A crucial observation from

Table 5 is that the curvature difference

increases systematically with Bond number, rising from

at

to

at

. This reflects the fact that gravitational effects modify the pressure distribution within the droplet, leading to enhanced curvature asymmetry across the heterogeneous boundary. The pressure constants

and

become increasingly negative as Bond number grows, indicating that the reference pressure adjustment required to satisfy boundary conditions becomes more substantial when gravity competes with surface tension.

Despite these morphological changes, a fundamental geometric invariant persists: the asymmetry parameter remains constant for all Bond numbers since the contact angles are fixed. Consequently, the length ratio maintains the same value of across all cases shown, as dictated by the spreading condition equation. This demonstrates that while the Bond number profoundly affects the vertical extent and curvature distribution of the droplet, it does not alter the horizontal partitioning of the droplet base as determined by the contact angle ratio. The spreading condition, which governs the equilibrium position relative to the heterogeneous boundary, is independent of gravitational effects and depends solely on the contact angle configuration.

The transition from to thus represents a crossover from capillary-dominated to gravity-influenced droplet shapes, where the competition between surface tension and gravitational body forces reshapes the interface while preserving the fundamental asymmetry encoded in the contact angle boundary conditions. This behavior is critical for understanding droplet dynamics across different length scales, from microscale droplets in microfluidic devices (small ) to millimeter-scale drops on patterned surfaces (moderate to large ).

The comprehensive results presented in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 validate the theoretical framework and demonstrate the robustness of the two-stage numerical method across a wide parameter space. The asymmetry parameter

emerges as the fundamental quantity governing droplet geometry on heterogeneous surfaces, capturing the competition between spreading forces at opposite contact lines.

Figure 2 reveals that

exhibits strong nonlinear sensitivity to contact angle variations, particularly near

where the tangent function diverges, creating regions of extreme asymmetry. Physically realizable equilibrium configurations exist only when both contact angles lie on the same side of

; mixed hydrophilic–hydrophobic boundaries (

or vice versa) yield negative spreading functions that violate equilibrium conditions, driving spontaneous droplet migration.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 systematically explore the contact angle parameter space for fixed Bond number

, revealing fundamentally different behaviors in hydrophilic versus hydrophobic regimes. For hydrophilic surfaces (

Figure 3), droplets preferentially spread toward regions with smaller contact angles (better wettability), producing asymmetric shapes where the maximum height shifts away from the heterogeneous boundary. The length ratio

can exceed 14 when contact angle disparity is large (

,

), while maximum heights decrease as spreading becomes more favorable. Conversely, hydrophobic surfaces (

Figure 4) exhibit counterintuitive behavior: droplets occupy greater area on the side with larger contact angles (poorer wettability), reflecting the dominance of capillary pressure gradients that favor extension into regions resisting wetting. These droplets maintain substantially greater heights (

–

) compared to hydrophilic counterparts, adopting compact, nearly spherical geometries that minimize contact area. The curvature difference

serves as a diagnostic for asymmetry strength, increasing monotonically with contact angle disparity in both regimes.

Figure 5 isolates the effect of gravitational deformation by varying Bond number from

(capillary-dominated) to

(gravity-influenced) while holding contact angles fixed at

and

. The results demonstrate systematic gravitational flattening: maximum height decreases from

to

as droplet weight increasingly distorts the interface from its capillary-determined shape. Remarkably, the length ratio

remains constant across all Bond numbers, confirming that horizontal partitioning is determined exclusively by the spreading function ratio

and is independent of gravitational effects. The curvature difference

increases with Bond number, reflecting enhanced hydrostatic pressure contributions that amplify asymmetry in the normal stress balance. This invariance of the spreading condition under gravitational variation validates the theoretical prediction that contact line equilibrium positions are determined by interfacial energy considerations rather than body forces.

Collectively, these results establish that the spreading condition constitutes a universal equilibrium criterion for droplets on heterogeneous surfaces, valid across diverse wettability contrasts and gravitational regimes. The two-stage computational strategy—computing a reference shape via parametric Young–Laplace integration followed by algebraic translation to satisfy spreading equilibrium—proves both accurate and efficient, converging within seconds for typical parameter values. The physical insights gained illuminate fundamental mechanisms in wetting phenomena: the spreading function encodes the unbalanced Young stress driving contact line motion, while the Bond number controls morphological transitions from spherical caps to puddle-like geometries without affecting lateral asymmetry ratios. These findings provide quantitative predictions for droplet manipulation on chemically patterned substrates, with implications for microfluidic transport, surface coating technologies, and self-assembly processes where controlled wettability gradients guide fluid motion.

The numerical results presented above can be interpreted more explicitly in terms of the interplay between curvature-induced pressure differences and gravitational flattening, providing connections to established equilibrium-shape models and curvature-based analyses. The Young–Laplace equation

fundamentally relates interface curvature to the pressure distribution within the droplet. The pressure constants

and

represent the dimensionless pressure jumps at the maximum height

, and their difference

quantifies the curvature discontinuity at the heterogeneous boundary. From

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3, we observe that

increases systematically with both contact angle disparity and Bond number, indicating enhanced asymmetry in the normal stress balance. This curvature difference drives internal pressure gradients that would induce flow in dynamic systems, but at static equilibrium, these pressure gradients are balanced by the constraint of fixed contact angles at contact lines.

The unbalanced Young stress at each contact line, encoded in the spreading function

, originates from the horizontal component of the Young force

. At equilibrium, the spreading condition

ensures that the net horizontal force integrated over the droplet base vanishes. This balance is achieved through geometric adjustment of contact line positions rather than changes in contact angles, which are prescribed by surface chemistry. The spreading function diverges as

(

Figure 2), explaining the extreme sensitivity of droplet asymmetry in this regime where small contact angle variations produce large changes in the horizontal force balance.

Our Bond number study (

Figure 5,

Table 3) demonstrates gravitational flattening consistent with the qualitative behavior predicted by oblate spheroidal-cap models for sessile drops. As

increases from 0.01 to 0.7, the maximum height decreases from

to

(a 29% reduction), while the droplet footprint expands correspondingly to maintain constant volume. This systematic height reduction mirrors the transition from spherical caps at small

to puddle-like geometries at large

observed in classical sessile drop studies. Importantly, the horizontal partitioning ratio

remains invariant across this gravitational regime, confirming that the spreading condition depends exclusively on interfacial energy ratios rather than body forces. This decoupling between vertical shape distortion (governed by

) and horizontal force balance (governed by contact angle ratios) is a key insight for designing wettability-patterned surfaces.

For readers working with microfluidic droplet manipulation, it is useful to recognize that similar curvature-induced pressure differences underpin selective droplet splitting in microvalve networks and geometric routing in branched channels. Raveshi et al. [

27] demonstrated that single-layer microfluidic valves exploit differential curvature across constrictions to achieve selective droplet splitting based on droplet size. Lubarda et al. [

18] analyzed the equilibrium droplet shape on an ellipsoidal cap using energy minimization and curvature-pressure relationships analogous to our Young–Laplace formulation. Combining our static equilibrium analysis with such pressure-balance models could yield predictive design criteria for geometric-controlled splitting and routing in wettability-patterned microchannels. The spreading condition provides the equilibrium partitioning for a given chemical pattern, while dynamic models incorporating capillary number and contact line mobility would describe transient approach to equilibrium.

The framework developed here also connects to curvature-driven droplet behavior in confined geometries. The pressure constant C in the Young–Laplace equation can be interpreted as the Laplace pressure at the droplet apex normalized by surface tension and characteristic length. At heterogeneous boundaries, the jump creates a pressure gradient that, if contact lines were mobile, would drive migration toward the lower-pressure region. Our static solutions represent the terminal state after such migration ceases due to contact angle constraints. This perspective suggests that dynamic simulations incorporating our equilibrium criterion as a target state could model time-dependent droplet repositioning on programmable wettability surfaces, relevant for digital microfluidics and lab-on-a-chip applications.

Recent work by Long and Gao [

19] investigated droplet dynamics on chemical steps using lubrication theory within a dynamic framework, while our study addresses static equilibrium configurations where the droplet straddles the heterogeneous boundary. The two studies employ different characteristic length scales, leading to systematic differences in both dimensionless lengths and Bond numbers. Long & Gao [

19] use the initial contact radius

as the reference length, while we use

based on the droplet area. For a 2D droplet with parabolic profile, the volume is

, giving the scaling factor

for

(our

Table 3 configuration). This scaling factor relates both dimensionless lengths and Bond numbers between the two formulations

Table 6 presents a comprehensive comparison after applying these scaling conversions. Long & Gao report a migration length of

(in their dimensionless units) for

, which converts to

in our reference frame. However, their analysis does not explicitly examine how this length varies with Bond number, as their focus was primarily on contact angle ratio effects.

The differences (12–30%) after scaling correction arise from fundamental distinctions in problem formulation. Long & Gao’s

characterizes the droplet during quasi-steady migration with moving contact lines and finite velocity. Our solution represents static equilibrium with pinned contact lines where net forces vanish. Their dynamic formulation incorporates Cox–Voinov relations at moving contact lines with slip length, introducing boundary layer regions that affect overall droplet length. Our formulation prescribes stationary contact angles as boundary conditions, eliminating boundary layer effects associated with contact line motion. Long & Gao’s framework assumes

, which becomes marginal for

. Our full Young–Laplace formulation without small-angle approximation provides higher accuracy for moderate contact angles. Additionally, the Bond number conversion reveals important differences in gravitational regime. The scaling relationship

means that our moderate Bond numbers correspond to significantly larger values in their reference frame. Lubrication theory requires

(evaluated in their frame). As shown in

Table 6, our

corresponds to their

, giving

, which is marginal for lubrication validity. At our

, this parameter becomes

, severely violating the lubrication approximation. This systematic deviation from the regime where lubrication theory is valid contributes to the increasing discrepancy from 12% to 30% as Bond number increases, though the absence of explicit

Bo-dependence data in Long & Gao’s work precludes direct quantitative comparison. The quantitative differences highlight the distinction between dynamic migration and static equilibrium, which may be experimentally distinguishable through time-resolved measurements or hysteresis studies.

Our model makes several idealizations that must be acknowledged when comparing with experiments or full 3D simulations. First, the 2D cylindrical geometry neglects out-of-plane curvature effects present in 3D axisymmetric droplets, which typically reduce spreading lengths by 10–20% compared to 2D predictions. Second, we assume static equilibrium with prescribed equilibrium contact angles, neglecting contact angle hysteresis, contact line pinning, and dynamic effects that dominate in real systems with moving contact lines. Third, the horizontal translation approximation () becomes less accurate for very large Bond numbers () or extreme contact angle disparities where significant shape deformation occurs during translation. Fourth, we neglect line tension effects and disjoining pressure, which become important for nanoscale droplets or near complete wetting. These limitations define the applicability range of our model as moderate-size droplets (10 μm–1 mm), moderate Bond numbers (), and both contact angles on the same side of .

Direct experimental validation through high-resolution imaging of droplets on fabricated chemical step patterns would provide the most rigorous test of our predictions. Key measurable quantities include the contact line position ratio , maximum height , and droplet profile . Experiments should focus on the regime where our idealizations are most valid: quasi-static deposition on well-characterized surfaces with minimal hysteresis, moderate droplet sizes to avoid both gravitational puddle formation and capillary length effects, and contact angle combinations satisfying . Comparison with 3D experiments would require extending our 2D framework to axisymmetric geometry, which is feasible using the same parametric methodology with cylindrical coordinates.

The systematic trends observed in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 and

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 can be understood through fundamental force balance principles. The Bond number increase from 0.01 to 0.7 causes progressive droplet flattening because the gravitational body force

in the Young–Laplace equation becomes increasingly significant relative to the capillary pressure

. At small Bond numbers, surface tension dominates and minimizes interfacial area by adopting nearly spherical profiles with uniform curvature. As Bond number increases, the hydrostatic pressure variation

within the droplet grows, requiring larger horizontal extent to maintain pressure balance at the contact lines. This gravitational spreading reduces

from 1.002 to 0.710 while increasing the footprint proportionally. The key physical insight is that this vertical deformation occurs without affecting the horizontal force balance that determines

, because the spreading condition arises purely from interfacial energy ratios at the contact lines where

and gravitational contributions vanish.

Asymmetric contact angles induce droplet distortion through unbalanced Young stresses at the two contact lines. At each contact line, the horizontal component of the Young force per unit length is , but the contact line position amplifies this force by the lever arm effect, giving a net torque-like contribution proportional to . Equilibrium requires these contributions to balance, yielding . When on hydrophilic surfaces, forces to achieve balance, explaining the preferential spreading toward smaller contact angle regions. For hydrophobic surfaces where both angles exceed , the spreading function increases more rapidly with angle, causing the counterintuitive behavior where larger contact angles correspond to greater extension. This reversal occurs because the tangent function diverges as , making extremely sensitive to contact angle in the hydrophobic regime.

The energy landscape for droplets on heterogeneous surfaces exhibits multiple local minima corresponding to different contact line configurations. Our analysis identifies the global minimum satisfying the spreading condition, but metastable states can exist when contact angle hysteresis provides energy barriers preventing relaxation to equilibrium. Contact line pinning at surface defects or chemical heterogeneities creates additional local minima that trap droplets in configurations different from the global energy minimum predicted by our static analysis.

The magnitude of the energy barrier between metastable and equilibrium states can be estimated from the work required to move the contact line across a pinning site. For a contact line of unit length moving a distance

across a region with contact angle difference

, the energy change is approximately

where

represents the characteristic pinning length scale, typically on the order of surface roughness or chemical heterogeneity size. This energy barrier must be compared to the available thermal energy

or external driving forces to determine whether the droplet can overcome pinning and reach the equilibrium configuration.

Contact angle hysteresis, characterized by the difference between advancing and receding contact angles

, provides a measure of the energy dissipation during contact line motion [

13,

30]. When the prescribed contact angles

and

differ by more than the hysteresis window, multiple equilibrium positions become possible depending on the direction of droplet approach. Experimental studies [

14] have shown that droplets on surfaces with contact angle hysteresis can exhibit stick-slip motion and remain pinned in configurations far from the global energy minimum. For contact angle differences exceeding approximately

radians (30 degrees), energy barriers become sufficiently large that droplets can remain trapped in metastable configurations on experimental timescales of minutes to hours, particularly when surface defects or chemical patterns provide strong pinning sites [

29].

The spreading condition derived here represents the ultimate equilibrium state approached asymptotically as hysteresis effects diminish and the system relaxes to the global energy minimum. In the limit of vanishing hysteresis and smooth, defect-free surfaces, our predictions should accurately describe experimental droplet configurations. However, practical droplet manipulation on real surfaces must account for kinetic barriers that our static analysis does not capture. The timescale for reaching equilibrium depends on contact line mobility, viscous dissipation, and the height of energy barriers relative to available driving forces, requiring dynamic models such as those developed by Long & Gao [

19] for chemically driven migration or Semprebon & Brinkmann [

14] for hysteresis-dominated systems.

6. Conclusions

This study establishes a rigorous theoretical and computational framework for predicting equilibrium configurations of asymmetric droplets on surfaces with sharp wetting boundaries. The work makes three primary contributions to wetting theory and microfluidic design.

First, we derive from first principles a universal spreading condition that governs horizontal partitioning of droplets across heterogeneous boundaries. This condition emerges naturally from Lagrange multiplier analysis of the constrained Gibbs free energy functional and remains valid for arbitrary Bond numbers under the horizontal translation approximation. The spreading function encodes the unbalanced Young stress at each contact line, providing a direct physical interpretation of the force balance required for equilibrium. Unlike previous analyses that rely on numerical minimization of coupled differential–algebraic systems, our spreading condition reduces to an explicit algebraic relation that enables rapid prediction of equilibrium contact line positions without iterative computation.

Second, we demonstrate the decoupling of vertical and horizontal equilibrium mechanisms through systematic Bond number variation. Gravitational effects profoundly influence droplet height and curvature distribution, reducing maximum height by up to 30% as Bond number increases from 0.01 to 0.7, yet the contact line position ratio remains invariant across this gravitational regime. This independence validates the theoretical prediction that horizontal partitioning depends exclusively on interfacial energy ratios rather than body forces, establishing a fundamental separation of scales in droplet equilibrium problems. The practical implication is that wettability pattern design for controlled droplet positioning can proceed independently of gravitational considerations, simplifying optimization for applications ranging from microscale lab-on-chip devices to millimeter-scale coating processes.

Third, we develop an efficient two-stage computational strategy that exploits this decoupling. By first computing a reference droplet shape through parametric Young–Laplace integration using Newton–Raphson iteration, then applying algebraic translation to satisfy the spreading condition, we reduce computational cost by orders of magnitude compared to fully coupled approaches. The parametric formulation using tangent angle as the independent variable naturally handles vertical tangent singularities near contact lines, ensuring robust convergence within 5–10 iterations to machine precision accuracy.

The physical insights revealed by our analysis advance understanding of wetting phenomena on heterogeneous surfaces. Hydrophilic surfaces exhibit intuitive behavior where droplets spread preferentially toward regions with better wettability, adopting flattened asymmetric profiles with maximum heights around 0.8–1.3 dimensionless units. Conversely, hydrophobic surfaces display counterintuitive spreading toward regions with poorer wettability, maintaining tall compact geometries with heights 1.5–1.8 that minimize interfacial area. The asymmetry parameter exhibits extreme sensitivity near contact angles of due to the tangent function divergence, creating a narrow transition regime where modest contact angle variations produce order-of-magnitude changes in droplet geometry. Most significantly, mixed hydrophilic–hydrophobic boundaries yield negative spreading functions that violate equilibrium conditions, explaining the spontaneous droplet migration observed experimentally in such configurations and providing quantitative criteria for predicting when static equilibrium becomes impossible.

Our static equilibrium solutions show systematic differences (12–30%) with Long & Gao’s [

19] dynamic lubrication theory predictions (

Table 4). These differences are physically meaningful rather than errors, as they reflect the distinction between quasi-steady migration states (dynamic, moving contact lines) and true equilibrium configurations (static, pinned contact lines). The discrepancy increases with Bond number because lubrication theory requires

, which is violated at higher

values. This comparison validates our model within its intended regime (static equilibrium) while highlighting the different physics captured by dynamic models.

The model has well-defined applicability limits that must be acknowledged for proper application. The two-dimensional cylindrical geometry neglects out-of-plane curvature effects present in three-dimensional axisymmetric droplets, which typically reduce spreading lengths by 10–20 percent compared to our predictions. The assumption of static equilibrium with prescribed equilibrium contact angles excludes contact angle hysteresis, contact line pinning, and dynamic effects that dominate in systems with moving contact lines or surface defects. The horizontal translation approximation becomes less accurate for very large Bond numbers exceeding unity or extreme contact angle disparities where significant shape deformation accompanies translation. Line tension effects and disjoining pressure, important for nanoscale droplets or near-complete wetting conditions, are neglected in the continuum Young–Laplace framework.

Future extensions should address four key directions. Incorporating contact angle hysteresis and contact line mobility would capture dynamic wetting transitions, metastable states, and the energy barriers between configurations that determine practical droplet manipulation timescales. Extension to three-dimensional axisymmetric geometry is essential for quantitative comparison with experiments and realistic device design, feasible using the same parametric methodology with cylindrical coordinates and azimuthal angle as an additional degree of freedom. Including evaporation, thermal Marangoni effects, or surfactant transport would broaden applicability to non-isothermal systems and complex fluids relevant for applications such as inkjet printing, spray coating, and biochemical assays. Direct experimental validation through high-resolution imaging of droplets on fabricated chemical step patterns remains the most critical need, enabling measurement of contact line position ratios, maximum heights, and full profile shapes under controlled conditions with minimal hysteresis. Such experiments would rigorously test the spreading condition, quantify deviations from the horizontal translation approximation, and reveal potential physics beyond continuum theory such as line tension or molecular-scale interactions near wetting boundaries.

In conclusion, the spreading condition emerges as a universal equilibrium criterion for droplets on heterogeneous surfaces, independent of gravitational effects and valid across diverse wettability contrasts. The parametric numerical approach combines mathematical rigor with computational efficiency, making it a practical tool for both fundamental wetting studies and engineering design of microfluidic devices, self-cleaning surfaces, and droplet-based manufacturing processes. By elucidating the interplay between interfacial energy, contact angle asymmetry, and gravitational deformation, this work provides predictive capabilities for designing surfaces with tailored droplet manipulation properties and establishes a foundation for future investigations of dynamic wetting on chemically patterned substrates.