The Toxicity Assessment of Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles on Physical and Biochemical Quality of Rainbow Trout Spermatozoon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumentation and Reagents

2.2. Synthesis of Fe3O4 NPs

2.3. Collection and Exposure of Sperm Samples

2.4. Determination of Biochemical Oxidative Markers

2.5. Determination of Spermatozoon Kinematics

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

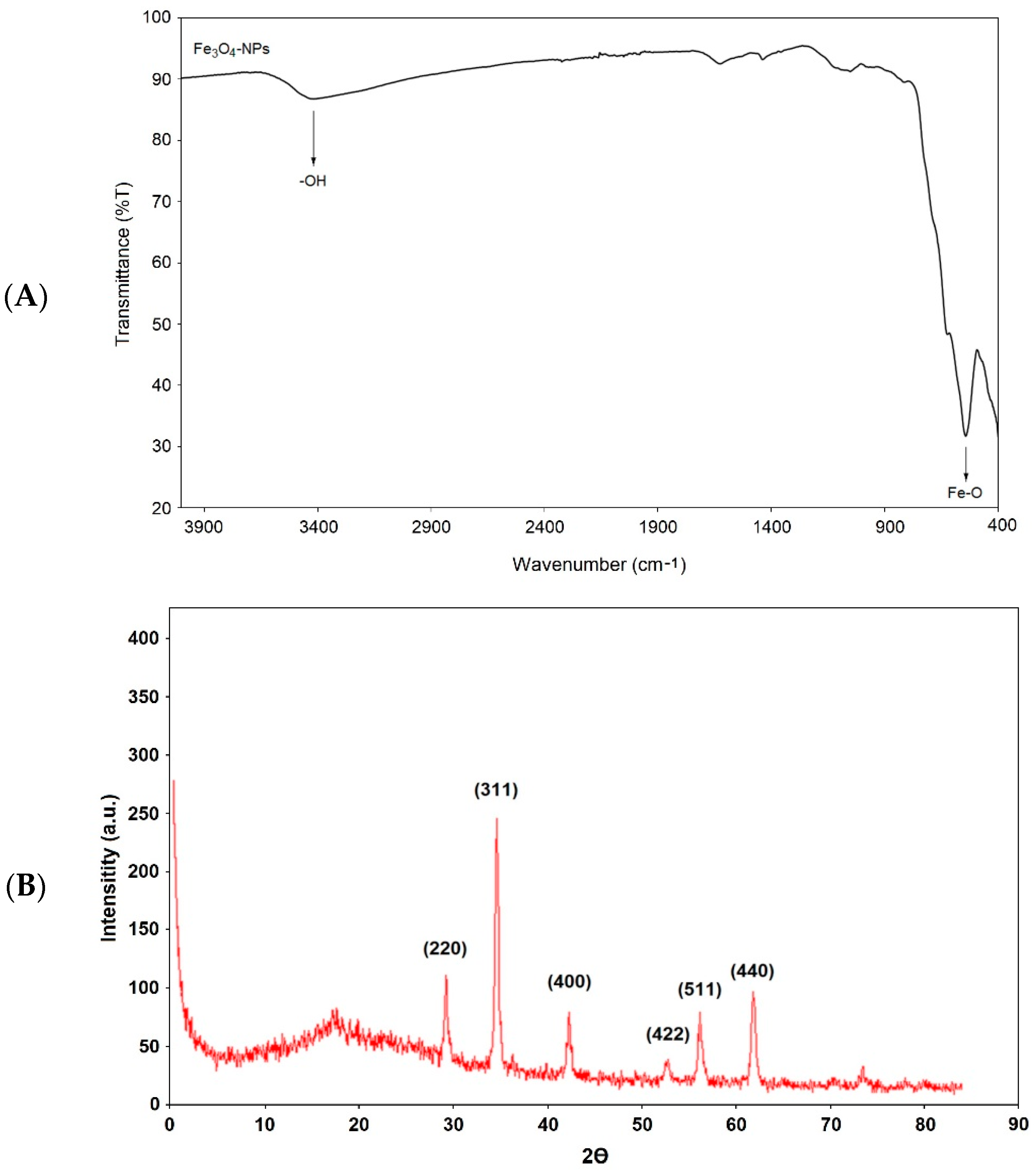

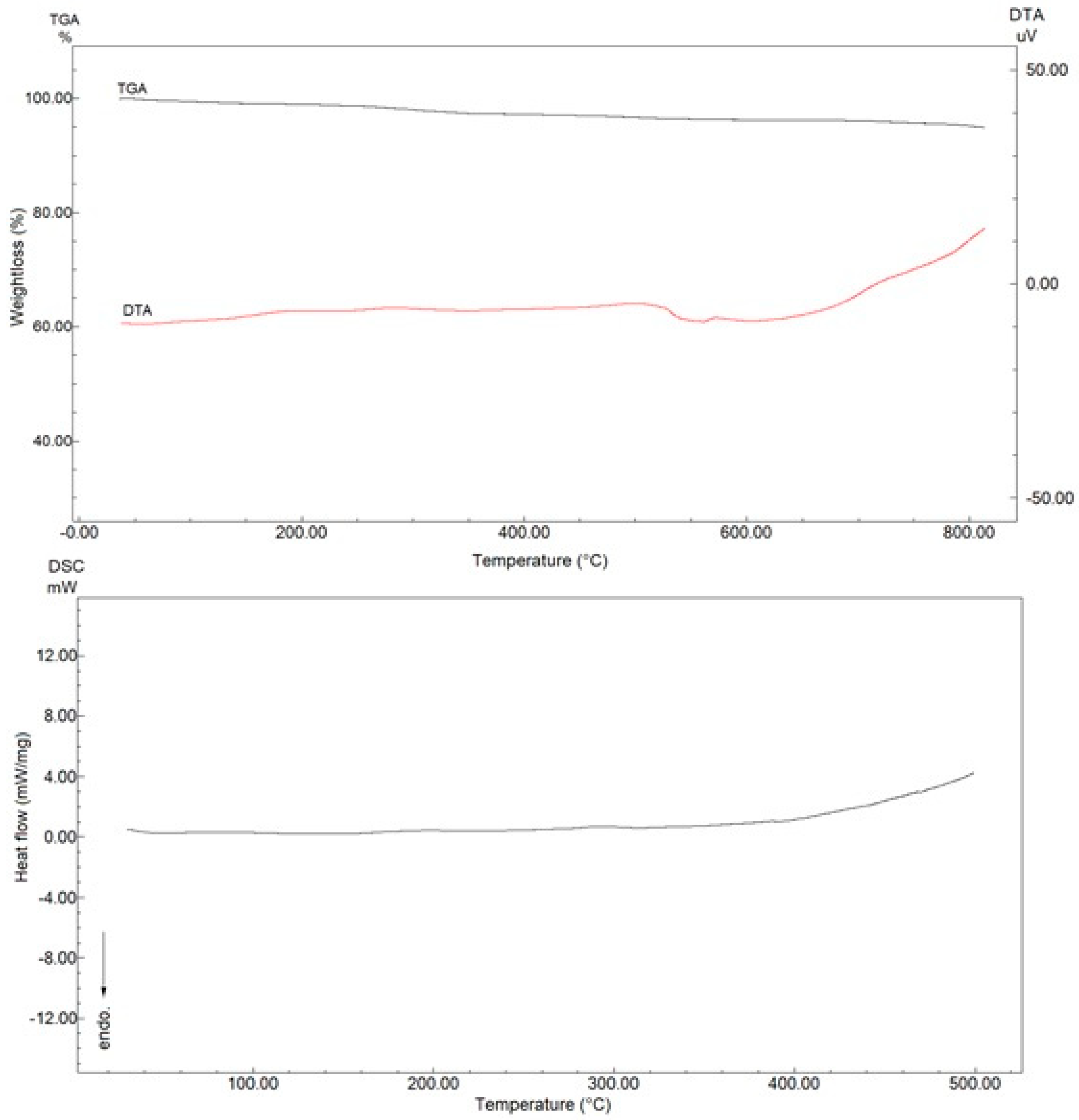

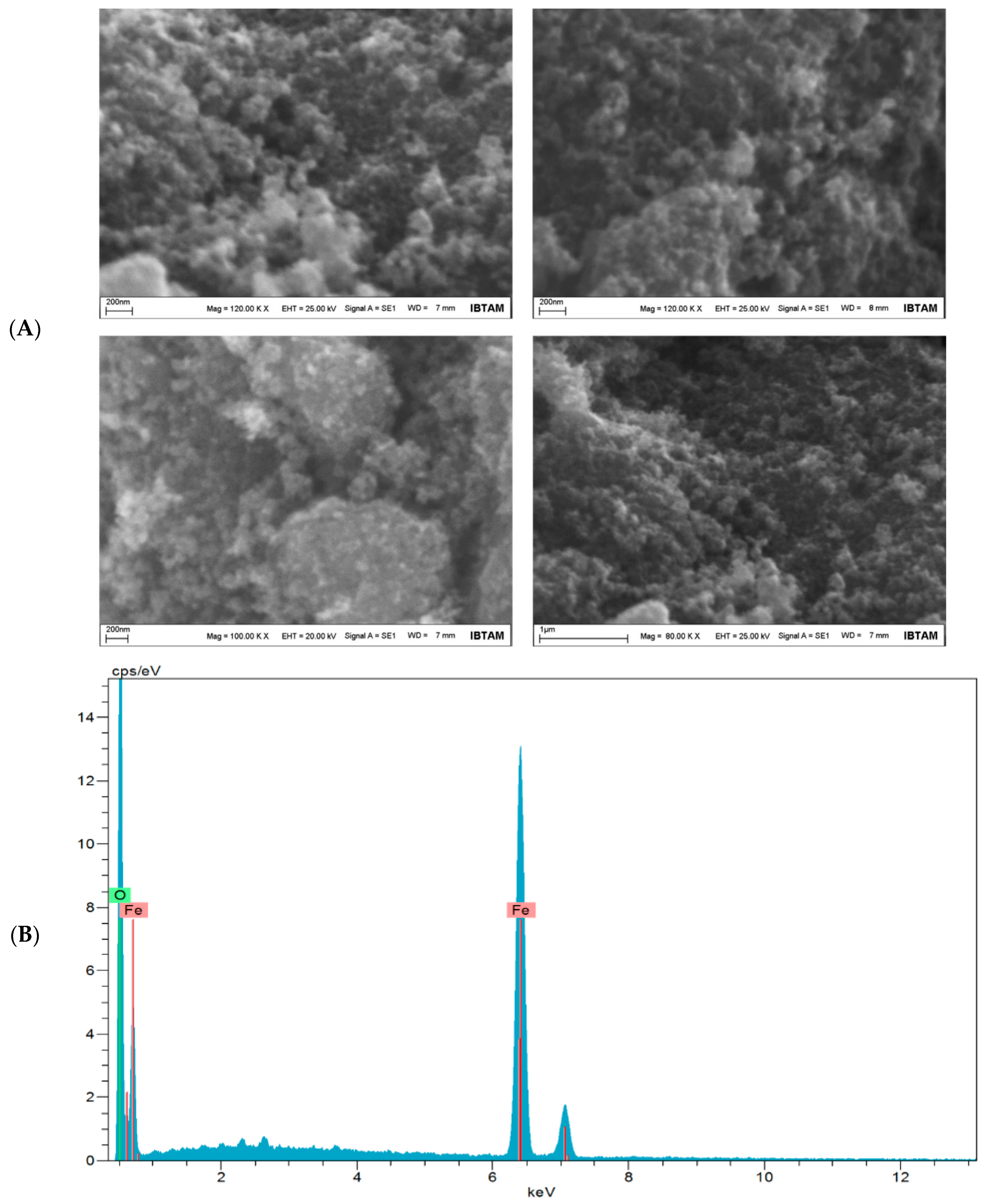

3.1. Characterization of Fe3O4 NPs

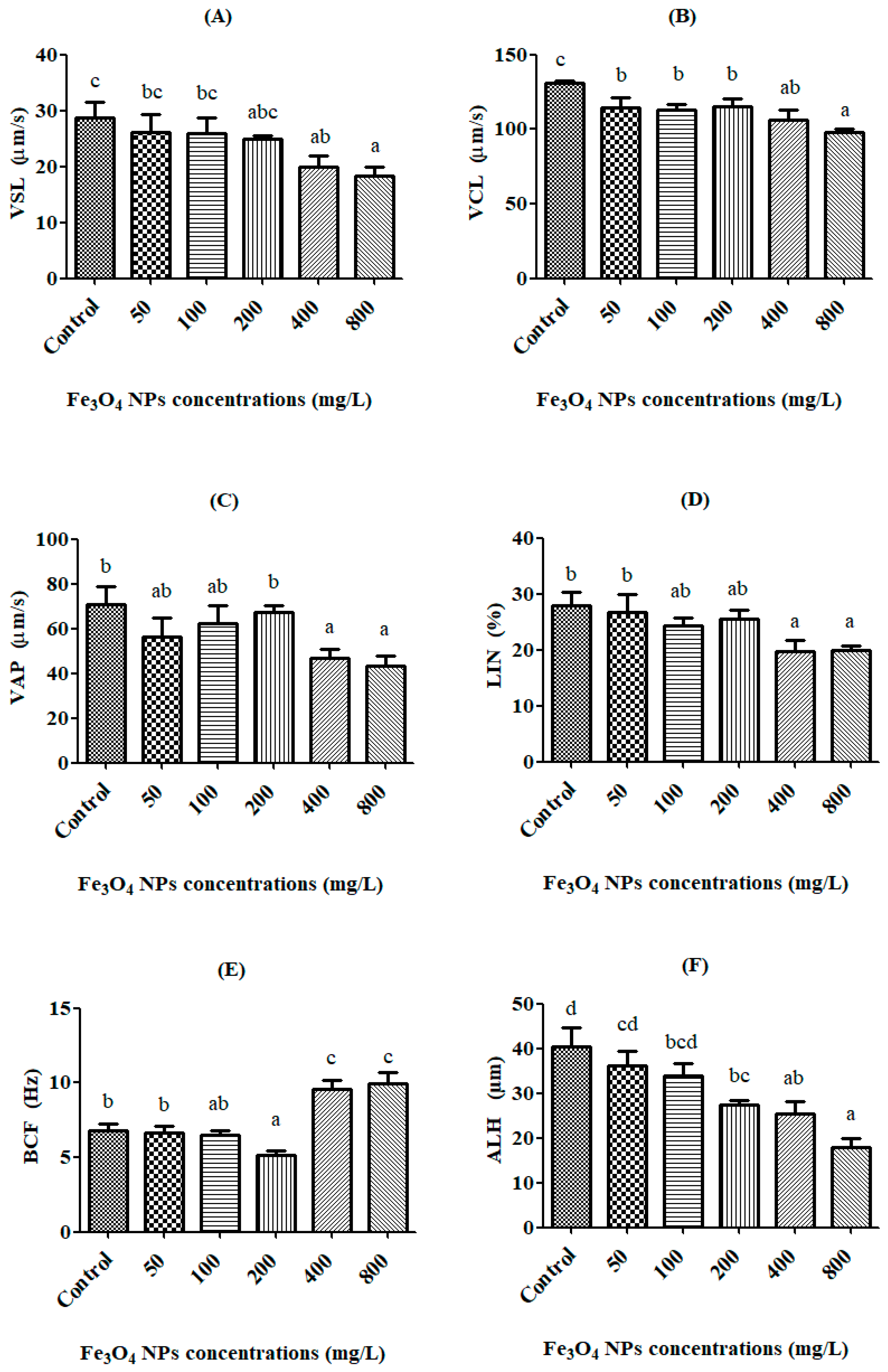

3.2. Spermatozoon Kinematics

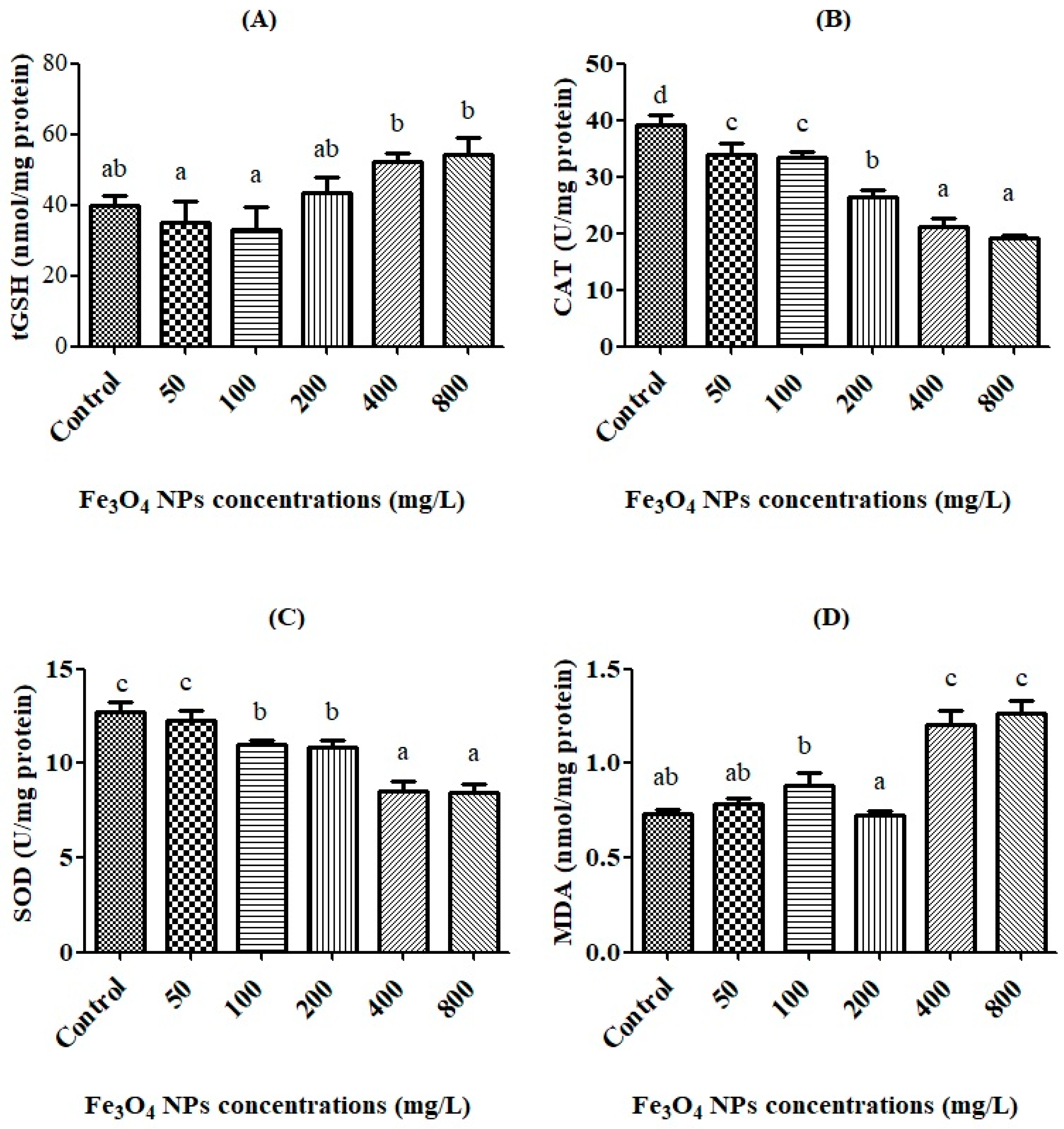

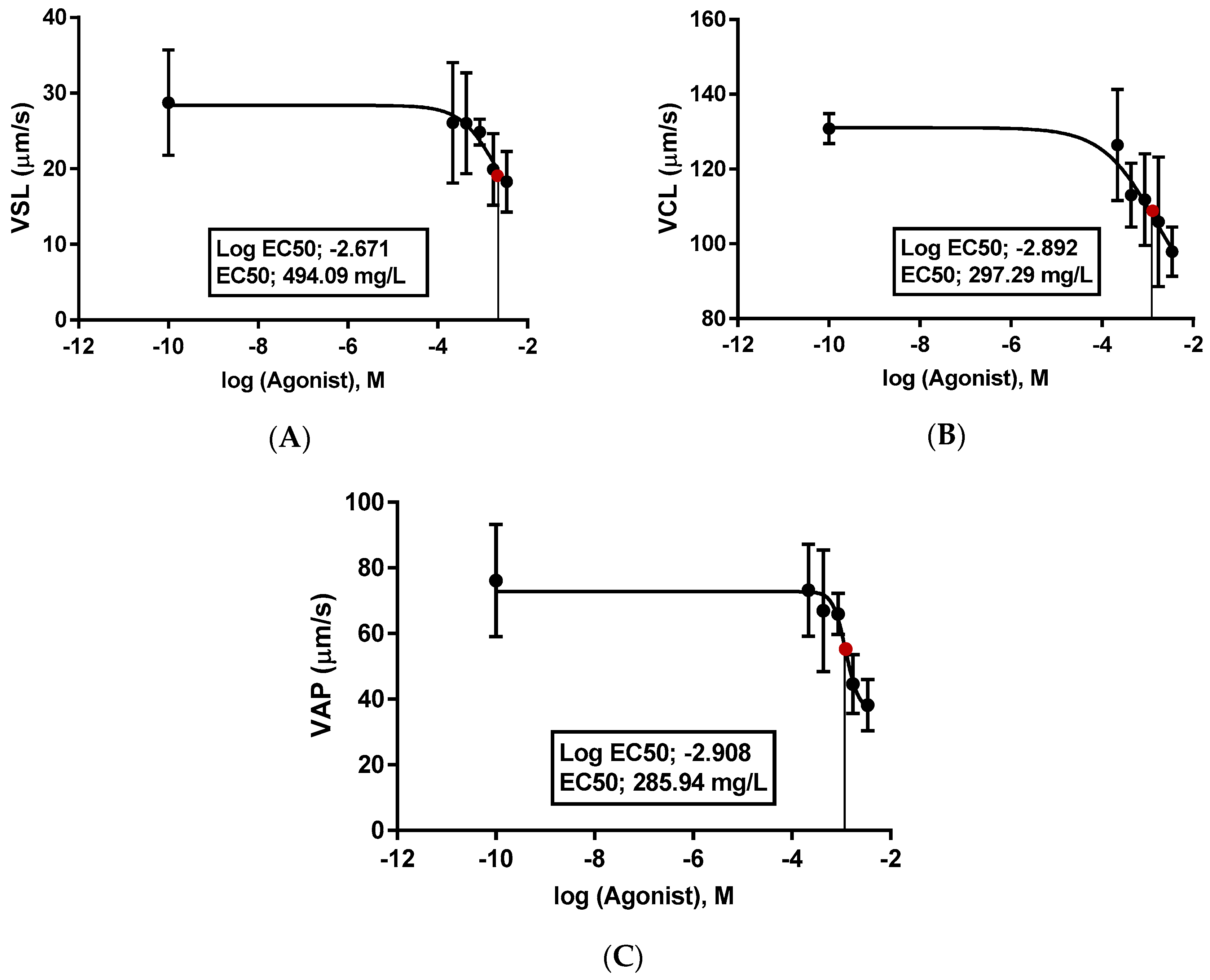

3.3. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and the Effective Concentration (EC50)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naha, P.C.; Byrne, H.J. Generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species and genotoxicity effect to exposure of nanosized polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers in PLHC-1 cells in vitro. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 132, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naha, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Byrne, H. Toxicology of Engineered Nanoparticles: Focus on Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.T.; Li, K.Y.; Meng, F.Q.; Lin, J.F.; Young, I.C.; Ivkov, R.; Lin, F.H. ROS-induced HepG2 cell death from hyperthermia using magnetic hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C. Environmental implications and applications of engineered nanoscale magnetite and its hybrid nanocomposites: A review of recent literature. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 322, 48–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, C.; Sun, Y.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Lin, D. Environmental transformations and ecological effects of iron-based nanoparticles. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 232, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naha, P.C.; Al Zaki, A.; Hecht, E.; Chorny, M.; Chhour, P.; Blankemeyer, E.; Yates, D.M.; Witschey, W.R.T.; Litt, H.I.; Tsourkas, A.; et al. Dextran coated bismuth-iron oxide nanohybrid contrast agents for computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 8239–8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teraphongphom, N.; Chhour, P.; Eisenbrey, J.R.; Naha, P.C.; Witschey, W.R.T.; Opasanont, B.; Jablonowski, L.; Cormode, D.P.; Wheatley, M.A. Nanoparticle Loaded Polymeric Microbubbles as Contrast Agents for Multimodal Imaging. Langmuir 2015, 31, 11858–11867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhour, P.; Gallo, N.; Cheheltani, R.; Williams, D.; Al-Zaki, A.; Paik, T.; Nichol, J.L.; Tian, Z.; Naha, P.C.; Witschey, W.R.; et al. Nanodisco balls: Control over surface versus core loading of diagnostically active nanocrystals into polymer nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 9143–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Kim, D.; Li, Y.; Hwang, G.; Naha, P.C.; Cormode, D.P.; Koo, H. Nanocatalysts promote Streptococcus mutans biofilm matrix degradation and enhance bacterial killing to suppress dental caries in vivo. Biomaterials 2016, 101, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Naha, P.C.; Hwang, G.; Kim, D.; Huang, Y.; Simon-Soro, A.; Jung, H.I.; Ren, Z.; Li, Y.; Gubara, S.; et al. Topical ferumoxytol nanoparticles disrupt biofilms and prevent tooth decay in vivo via intrinsic catalytic activity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remya, A.S.; Ramesh, M.; Saravanan, M.; Poopal, R.K.; Bharathi, S.; Nataraj, D. Iron oxide nanoparticles to an Indian major carp, Labeo rohita: Impacts on hematology, iono regulation and gill Na+/K+ATPase activity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2015, 27, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, M.; Demir, V.; Arslan, Z.; Kaya, H.; Yilmaz, S.; Camas, M. Chronic exposure of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) to iron oxide nanoparticles: Effects of particle morphology on accumulation, elimination, hematology and immune responses. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 177, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanth, K.; Trindade, T.; Duarte, A.C.; Pereira, E. Cytotoxicity and oxidative stress responses of silica-coated iron oxide nanoparticles in CHSE-214 cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Tian, S.; Cai, Z. Toxicity Assessment of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Early Life Stages. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J. Accumulation and elimination of iron oxide nanomaterials in zebrafish (Danio rerio) upon chronic aqueous exposure. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 30, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Lu, J.; Zhao, D. Effects of starch-coating of magnetite nanoparticles on cellular uptake, toxicity and gene expression profiles in adult zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadar, E.; Tarran, G.A.; Jha, A.N.; Al-Subiai, S.N. Stabilization of engineered zero-valent nanoiron with Na-acrylic copolymer enhances spermiotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3245–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.A.; Garner, K.; Miller, R.J.; Lenihan, H.S. Toxicity of Nano-Zero Valent Iron to Freshwater and Marine Organisms. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Xue, M.Y.; Luo, F.; Chen, W.C.; Zhu, B.; Wang, G.X. Developmental toxicity of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on cysts and three larval stages of Artemia salina. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 230, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambardella, C.; Mesarič, T.; Milivojević, T.; Sepčić, K.; Gallus, L.; Carbone, S.; Ferrando, S.; Faimali, M. Effects of selected metal oxide nanoparticles on Artemia salina larvae: Evaluation of mortality and behavioural and biochemical responses. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 4249–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashjoor, S.; Yousefzadi, M.; Zolgharnain, H.; Kamrani, E.; Alishahi, M. Organic and inorganic nano-Fe3O4: Alga Ulva flexuosa-based synthesis, antimicrobial effects and acute toxicity to briny water rotifer Brachionus rotundiformis. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatef, A.; Alavi, S.M.H.; Golshan, M.; Linhart, O. Toxicity of environmental contaminants to fish spermatozoa function in vitro—A review. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 140–141, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahnsteiner, F.; Mansour, N.; Kunz, F.A. The effect of antioxidants on the quality of cryopreserved semen in two salmonid fish, the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) and the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Theriogenology 2011, 76, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nynca, J.; Dietrich, G.J.; Dobosz, S.; Grudniewska, J.; Ciereszko, A. Effect of cryopreservation on sperm motility parameters and fertilizing ability of brown trout semen. Aquaculture 2014, 433, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, R. Some data on gametes preservation and artificial insemination in teleost fish. Actes Colloq. 1978, 8, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Özgür, M.E.; Balcıoğlu, S.; Ulu, A.; Özcan, İ.; Okumuş, F.; Köytepe, S.; Ateş, B. The in vitro toxicity analysis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles on kinematics and biochemical quality of rainbow trout sperm cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 62, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esrefoglu, M.; Akinci, A.; Taslidere, E.; Elbe, H.; Cetin, A.; Ates, B. Ascorbic acid and beta-carotene reduce stress-induced oxidative organ damage in rats. Biotech. Histochem. 2016, 91, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerboom, T.P.M.; Sies, H. Assay of Glutathione, Glutathione Disulfide, and Glutathione Mixed Disulfides in Biological Samples. Methods Enzymol. 1981, 77, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauvel, C.; Suquet, M.; Cosson, J. Evaluation of fish sperm quality. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2010, 26, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar, A.K.; Rastegari, A.A.; Amiri, R.; Ranjbakhsh, E.; Abbasi, M.; Khosropour, A.R. Characterization of Modified Magnetite Nanoparticles for Albumin Immobilization. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 705068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, K.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Musa, A.; Salmah, A.A.; Zamri, I. Use of Fe3O4 nanoparticles for enhancement of biosensor response to the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Sensors 2008, 8, 5775–5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, E.; Di Benedetto, A. Characterization of physicochemical and colloidal properties of hydrogel chitosan-coated iron-oxide nanoparticles for cancer therapy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 841, 12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulu, A.; Ozcan, I.; Koytepe, S.; Ates, B. Design of epoxy-functionalized Fe3O4 @MCM-41 core–shell nanoparticles for enzyme immobilization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Niu, C. Acute toxicity effects of perfluorooctane sulfonate on sperm vitality, kinematics and fertilization success in zebrafish. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2017, 35, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhartova, P.; Gazo, I.; Shaliutina-Kolesova, A.; Hulak, M.; Kaspar, V. Effects of tetrabrombisphenol A on DNA integrity, oxidative stress, and sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus) spermatozoa quality variables. Environ. Toxicol. 2015, 30, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, A.; Manfra, L.; Boni, R.; Rotini, A.; Migliore, L.; Tosti, E. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of CuO nanoparticles in sea urchin spermatozoa through oxidative stress. Environ. Int. 2018, 118, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokduman, K.; Bestepe, F.; Li, L.; Yarmush, M.L.; Usta, O.B. Dose-, treatment- and time-dependent toxicity of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles on primary rat hepatocytes. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaliutina, O.; Shaliutina-Kolešová, A.; Lebeda, I.; Rodina, M.; Gazo, I. The in vitro effect of nonylphenol, propranolol, and diethylstilbestrol on quality parameters and oxidative stress in sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus) spermatozoa. Toxicol. In Vitro 2017, 43, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afifi, M.; Saddick, S.; Abu Zinada, O.A. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles on the brain of Oreochromis niloticus and Tilapia zillii. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 23, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, D.; Fang, T.; Yu, L.; Sima, X.; Zhu, W. Science of the Total Environment Effects of nano-scale TiO2, ZnO and their bulk counterparts on zebra fish: Acute toxicity, oxidative stress and oxidative damage. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkaladi, A.; El-Deen, N.A.M.N.; Afifi, M.; Zinadah, O.A.A. Hematological and biochemical investigations on the effect of vitamin E and C on Oreochromis niloticus exposed to zinc oxide nanoparticles. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo, O.A.; Akinloye, O.; Adaramoye, O.A. Cerium oxide nanoparticle elicits oxidative stress, endocrine imbalance and lowers sperm characteristics in testes of balb/c mice. Andrologia 2018, 50, e12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Gao, Y.; Wu, H.; Hou, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, H. Physiological effect of anatase TiO2 nanoparticles on Lemna minor. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012, 31, 2147–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, R.; Paulraj, R. Oxidative stress mediated cytotoxicity of TiO2 nano anatase in liver and kidney of Wistar rat. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2012, 94, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özgür, M.E.; Ulu, A.; Balcıoğlu, S.; Özcan, İ.; Köytepe, S.; Ateş, B. The Toxicity Assessment of Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles on Physical and Biochemical Quality of Rainbow Trout Spermatozoon. Toxics 2018, 6, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics6040062

Özgür ME, Ulu A, Balcıoğlu S, Özcan İ, Köytepe S, Ateş B. The Toxicity Assessment of Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles on Physical and Biochemical Quality of Rainbow Trout Spermatozoon. Toxics. 2018; 6(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics6040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzgür, Mustafa Erkan, Ahmet Ulu, Sevgi Balcıoğlu, İmren Özcan, Süleyman Köytepe, and Burhan Ateş. 2018. "The Toxicity Assessment of Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles on Physical and Biochemical Quality of Rainbow Trout Spermatozoon" Toxics 6, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics6040062

APA StyleÖzgür, M. E., Ulu, A., Balcıoğlu, S., Özcan, İ., Köytepe, S., & Ateş, B. (2018). The Toxicity Assessment of Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles on Physical and Biochemical Quality of Rainbow Trout Spermatozoon. Toxics, 6(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics6040062