Perinatal BPAF Exposure Reprograms Offspring’s Immune–Metabolic Axis: A Multi-Omics Investigation of Intergenerational Hepatotoxicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Chemical Treatment

2.2. Glucose Tolerance Test and Insulin Tolerance Test

2.3. H&E Staining

2.4. Oil Red O Staining

2.5. Transcriptomic Analysis

2.6. Metabolomics Analysis

2.7. Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag)

2.8. Flow Cytometry

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

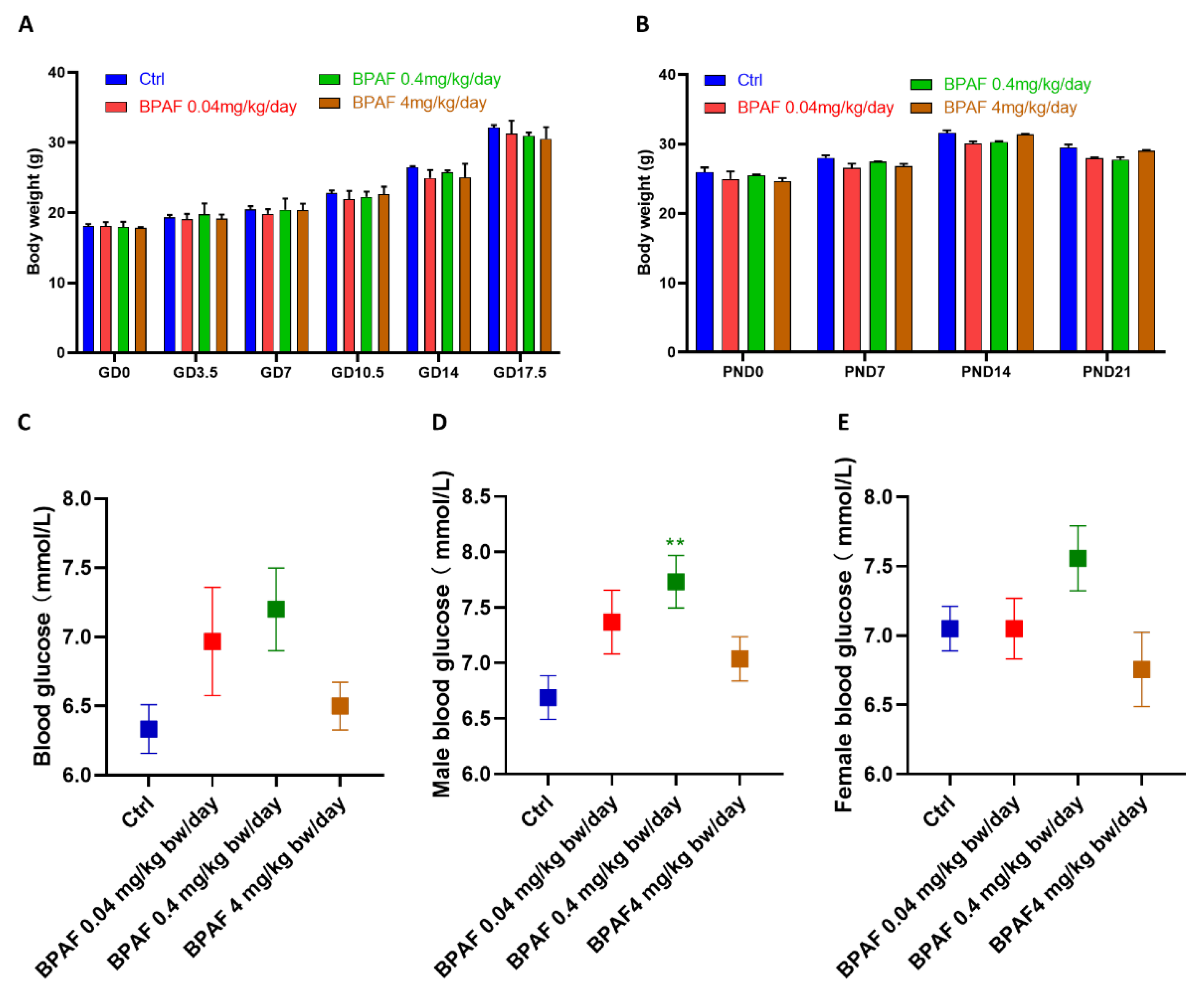

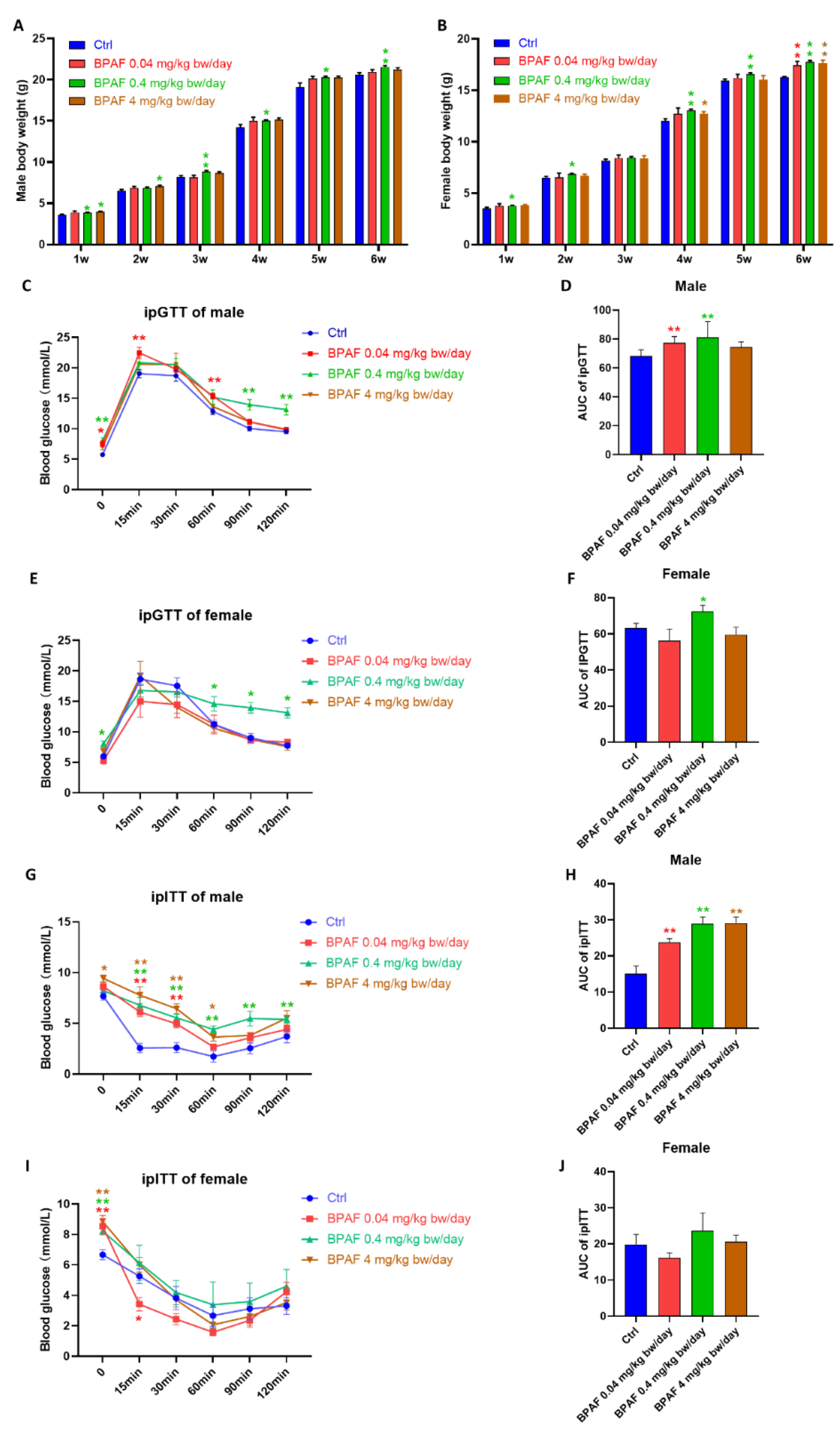

3.1. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Altered Body Weight and Glucose Metabolism in Offspring

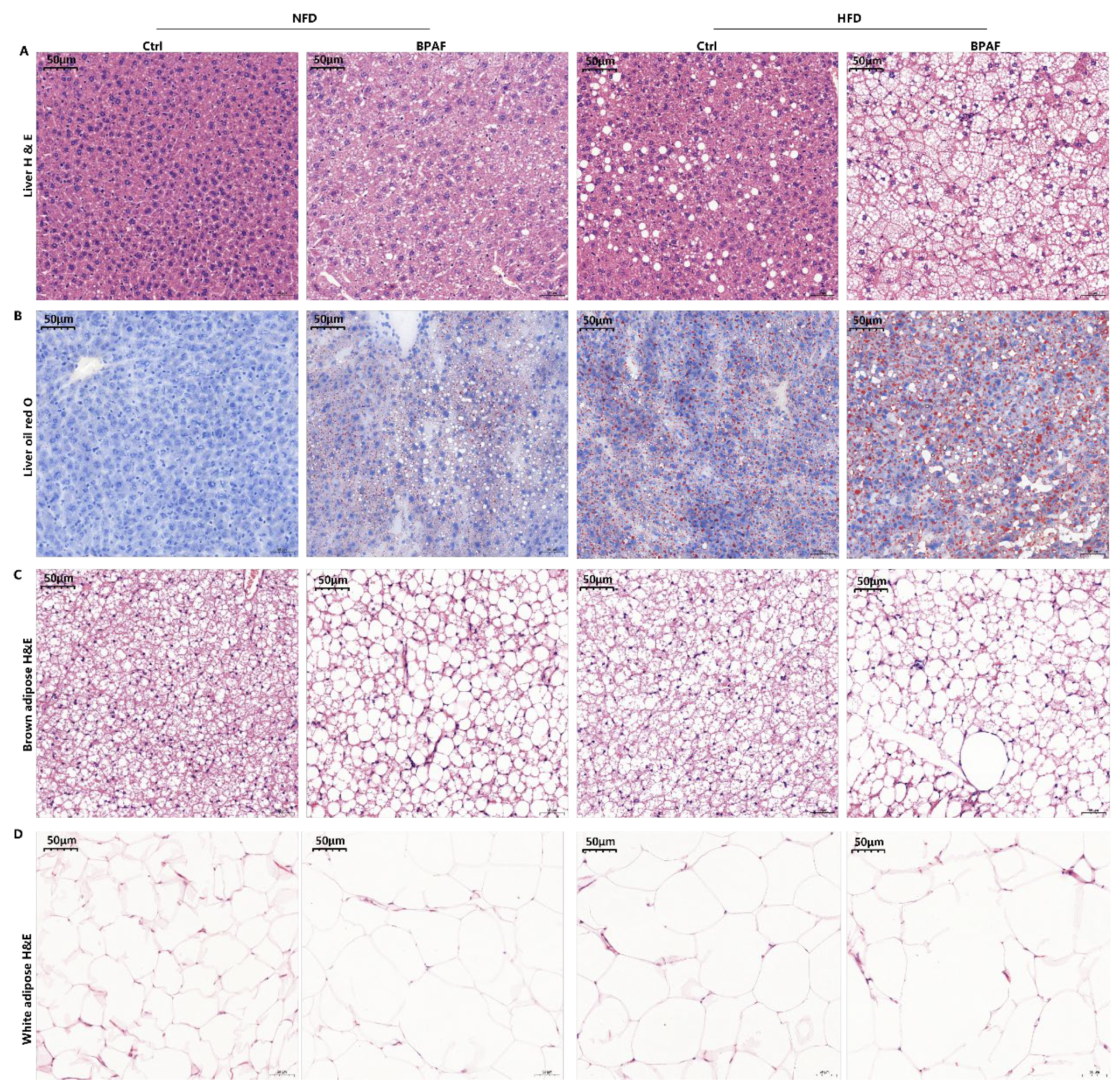

3.2. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Caused Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Adipose Hypotrophy

3.3. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Altered the Inflammatory Profile of the Spleen in Offspring

3.4. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Changed Hepatic Metabolome in Offspring

3.5. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Reprogramed Hepatic Transcriptome in Offspring

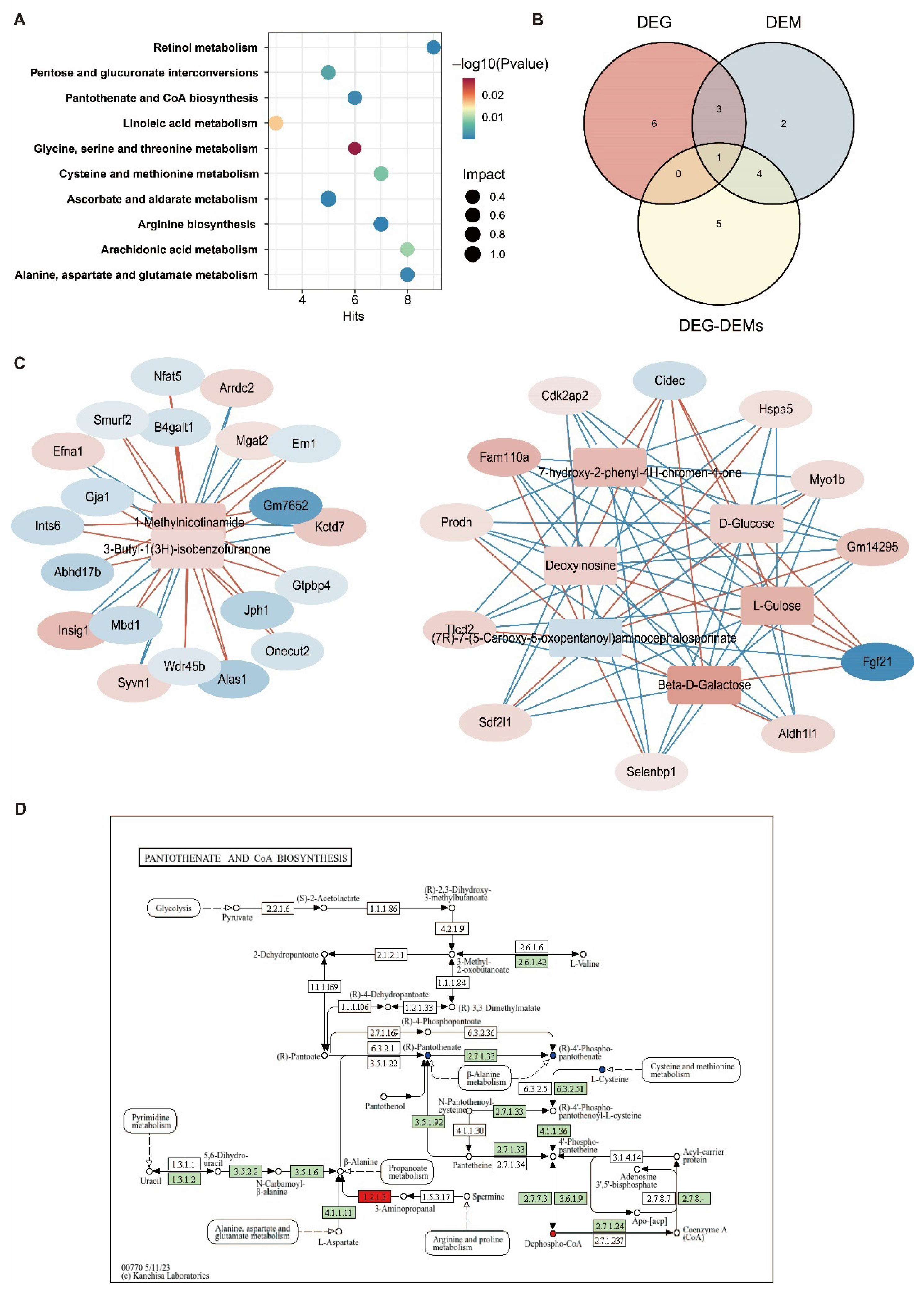

3.6. Joint Analysis of the Hepatic Transcriptome and Metabolome

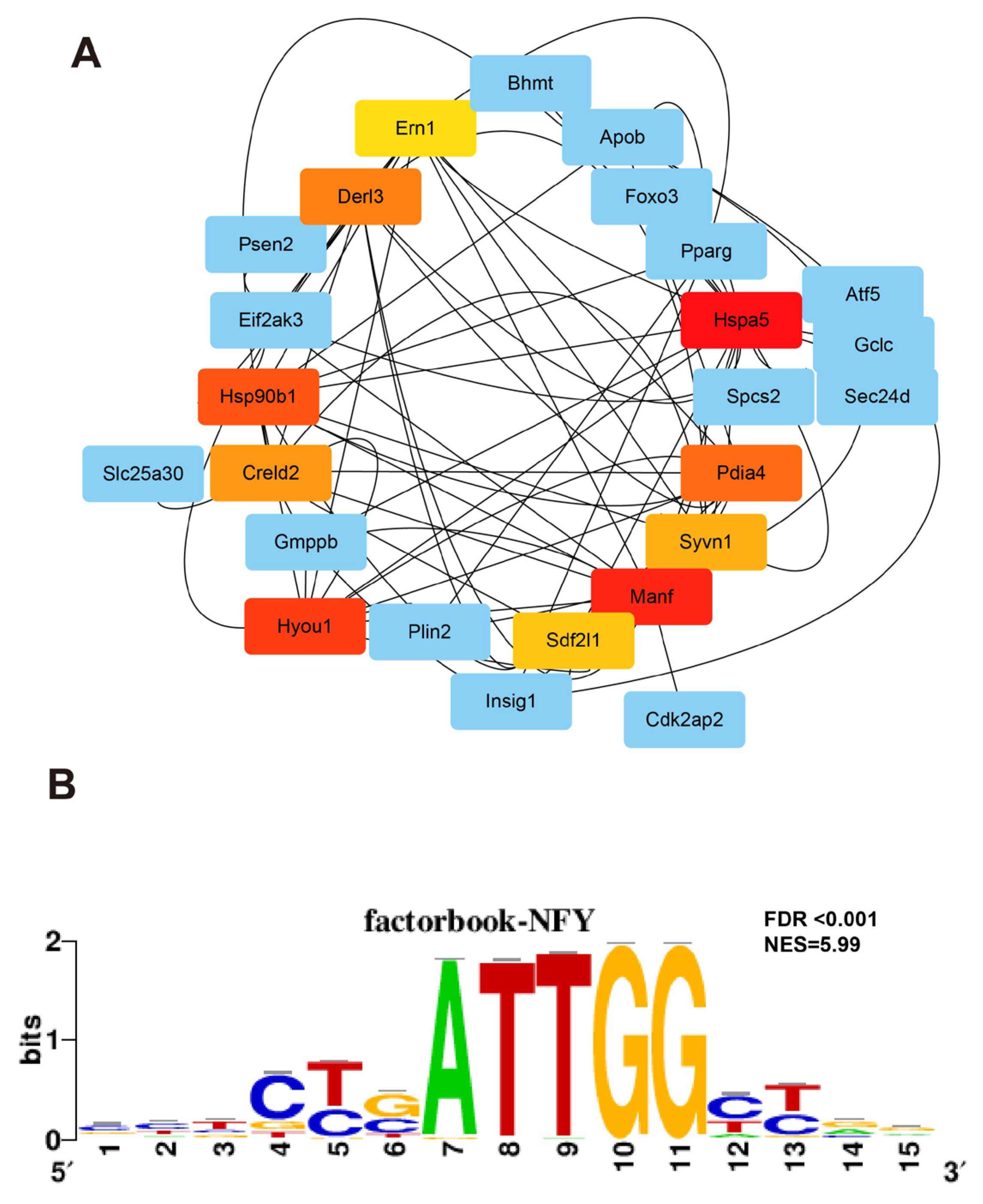

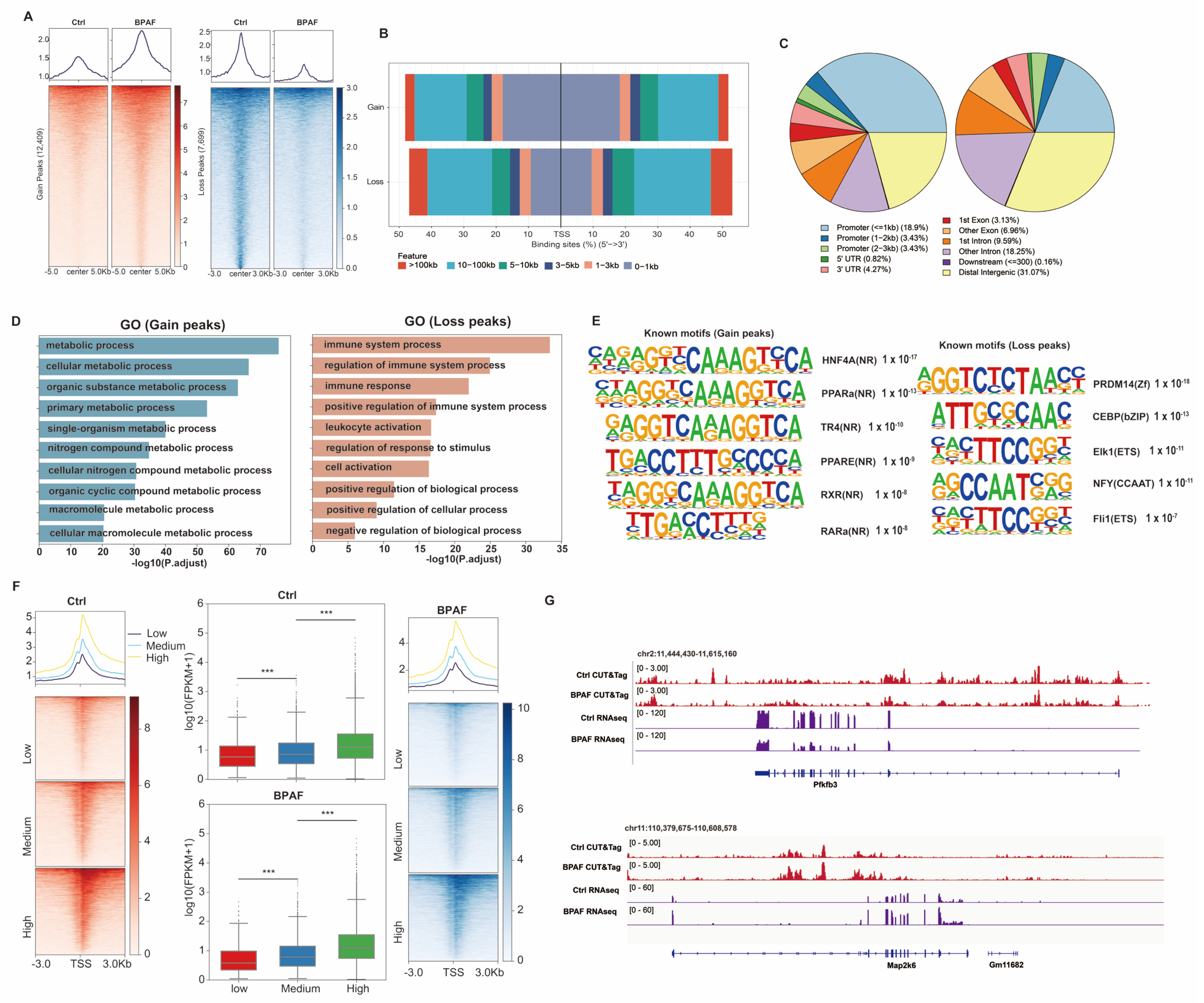

3.7. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Remodels Hepatic Enhancer Landscape to Regulate Gene Expressions in Offspring

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Total Bases (Gb) | Total Reads | Mapping Rate | FRIP (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl1 | 3.3 | 5,495,346 | 73.1 | 12.3 |

| Ctrl2 | 4.5 | 7,500,946 | 78.6 | 14.1 |

| BPAF1 | 6.8 | 11,277,323 | 85.1 | 12.9 |

| BPAF2 | 4.7 | 7,857,515 | 87.2 | 11.8 |

References

- Yuan, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Chu, H.; Zhang, Z. METTL3 regulates PM2.5-induced cell injury by targeting OSGIN1 in human airway epithelial cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kannan, K.; Tan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.L.; Wu, Y.; Widelka, M. Bisphenol Analogues Other Than BPA: Environmental Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Toxicity—A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L. Studies on electrochemical oxidation of estrogenic disrupting compound bisphenol AF and its interaction with human serum albumin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 276, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhuang, T.; Shi, W.; Liang, Y.; Liao, C.; Song, M.; Jiang, G. Serum concentration of bisphenol analogues in pregnant women in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 136100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, G.; Jiang, R.; Yan, Z.; Li, Y. Occurrence, toxicity and ecological risk of Bisphenol A analogues in aquatic environment—A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Quan, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhan, M.; Xu, W.; Lu, L.; Fan, J.; Wang, Q. Occurrence of bisphenol A and its alternatives in paired urine and indoor dust from Chinese university students: Implications for human exposure. Chemosphere 2020, 247, 125987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Shao, B. Simultaneous determination of seven bisphenols in environmental water and solid samples by liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1328, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Yao, Y.; Shao, Y.; Qu, W.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Q. Urinary bisphenol analogues concentrations and biomarkers of oxidative DNA and RNA damage in Chinese school children in East China: A repeated measures study. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Hong, Y.; Cai, Z. Occurrence and Partitioning of Bisphenol Analogues in Adults’ Blood from China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Gao, H. Effects of bisphenol A and bisphenol analogs on the nervous system. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Song, N.; Guo, R.; Chen, M.; Mai, D.; Yan, Z.; Han, Z.; Chen, J. Occurrence, distribution and sources of bisphenol analogues in a shallow Chinese freshwater lake (Taihu Lake): Implications for ecological and human health risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Zhu, L. Occurrence and partitioning of bisphenol analogues in water and sediment from Liaohe River Basin and Taihu Lake, China. Water Res. 2016, 103, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, M.; Jia, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liao, C.; Jiang, G. Occurrence, Distribution, and Human Exposure of Several Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Indoor Dust: A Nationwide Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 11333–11343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Tang, S.; Zhou, X.; Gao, R.; Liu, Z.; Song, X.; Zeng, F. Urinary concentrations of bisphenol analogues in the south of China population and their contribution to the per capital mass loads in wastewater. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 112398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Deng, M.; Li, J.; Du, B.; Lan, S.; Liang, X.; Zeng, L. Occurrence and Maternal Transfer of Multiple Bisphenols, Including an Emerging Derivative with Unexpectedly High Concentrations, in the Human Maternal-Fetal-Placental Unit. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3476–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Xie, J.; Mao, L.; Zhao, M.; Bai, X.; Wen, J.; Shen, T.; Wu, P. Bisphenol analogue concentrations in human breast milk and their associations with postnatal infant growth. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Liu, Y.; Cao, S.; Guo, R.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J. Biodegradation of bisphenol compounds in the surface water of Taihu Lake and the effect of humic acids. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 138164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzimski, T.; Szubartowski, S. Application of Solid-Phase Extraction and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection to Analyze Eleven Bisphenols in Amniotic Fluid Samples Collected during Amniocentesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, B.; Zeng, Q.; Zhao, X.; Dou, J.; Cao, J. Endocrine disrupting chemicals: A promoter of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1154837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, M.; Qi, L.S. Engineering 3D genome organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 22, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Du, L.L.; Ma, Q.L. Serum glycolipids mediate the relationship of urinary bisphenols with NAFLD: Analysis of a population-based, cross-sectional study. Environ. Health 2023, 21, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, X.; Xie, L.; He, Y.; Ouyang, J.P.; Huang, X.; et al. Serum concentrations of bisphenol A and its alternatives in elderly population living around e-waste recycling facilities in China: Associations with fasting blood glucose. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 169, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, B.; Han, L.; Wang, L.; Sun, H.; Chen, L. Association of urinary concentrations of bisphenols with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xia, W.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, B.; Xu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Cai, Z.; et al. Exposure to Bisphenol a Substitutes and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study in China. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, D.; Cao, G.; Shi, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, H.; Wen, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. IL-27 signalling promotes adipocyte thermogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature 2021, 600, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.C.; Cohenour, E.R.; Harnett, K.G.; Schuh, S.M. BPA, BPAF and TMBPF Alter Adipogenesis and Fat Accumulation in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells, with Implications for Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Tian, Y.; Xu, P.; Yue, H.; Sang, N. Bisphenol B and bisphenol AF exposure enhances uterine diseases risks in mouse. Environ. Int. 2023, 173, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Zhu, J.; Ling, Y.; Kuang, H. Gestational exposure to bisphenol AF causes endocrine disorder of corpus luteum by altering ovarian SIRT-1/Nrf2/NF-kB expressions and macrophage proangiogenic function in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 220, 115954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernis, N.; Masschelin, P.; Cox, A.R.; Hartig, S.M. Bisphenol AF promotes inflammation in human white adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2020, 318, C63–C72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, S.J.; Beavis, P.A.; Dawson, M.A.; Johnstone, R.W. Targeting the epigenetic regulation of antitumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 776–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.E.; Skinner, M.K. Epigenetic Transgenerational Inheritance of Obesity Susceptibility. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.; Brösamle, D.; Yuan, X.; Beyer, M.; Neher, J.J. Epigenetic control of microglial immune responses. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 323, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Sun, Q.; Huang, Z.; Bu, G.; Yu, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; et al. Arsenite exposure disturbs maternal-to-zygote transition by attenuating H3K27ac during mouse preimplantation development. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 331, 121856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lou, D.; Gao, Y.; Yu, J.; Kong, D.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Sodium arsenite exposure inhibits histone acetyltransferase p300 for attenuating H3K27ac at enhancers in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 357, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Lv, D.; Yang, L.; Zhou, J.; Yan, X.; Liu, Z.; Ma, K.; Yu, Y.; Liu, X.; Dong, Q. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate promotes benign prostatic hyperplasia through KIF11-Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Atlas, E. Bisphenol S- and bisphenol A-induced adipogenesis of murine preadipocytes occurs through direct peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Shukla, A.; Bunkar, N.; Shandilya, R.; Lodhi, L.; Kumari, R.; Gupta, P.K.; Rahman, A.; Chaudhury, K.; Tiwari, R.; et al. Exposure to ultrafine particulate matter induces NF-κβ mediated epigenetic modifications. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Rong, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wong, J.H.; Ng, T. First demonstration of protective effects of purified mushroom polysaccharide-peptides against fatty liver injury and the mechanisms involved. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, G.H.; Rios-Morales, M.; Gerding, A.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Olinga, P.; Bakker, B.M. The Effects of Butyrate on Induced Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Precision-Cut Liver Slices. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, S.; Ni, Y.; Qi, C.; Bai, S.; Xu, Q.; Fan, Y.; Ma, X.; Lu, C.; Du, G.; et al. Maternal BPAF exposure impaired synaptic development and caused behavior abnormality in offspring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Niu, R.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Hu, W.; Qin, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Xia, Y.; Fan, Y.; et al. Impact of Maternal BPA Exposure during Pregnancy on Obesity in Male Offspring: A Mechanistic Mouse Study of Adipose-Derived Exosomal miRNA. Environ. Health Perspect. 2025, 133, 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzellec, B.; Teleńczuk, M.; Cabeli, V.; Andreux, M. PyDESeq2: A python package for bulk RNA-seq differential expression analysis. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, X.; Peltz, G. GSEApy: A comprehensive package for performing gene set enrichment analysis in Python. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenot, E.A.; Roux, A.; Xu, Y.; Ezan, E.; Junot, C. Analysis of the Human Adult Urinary Metabolome Variations with Age, Body Mass Index, and Gender by Implementing a Comprehensive Workflow for Univariate and OPLS Statistical Analyses. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3322–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Zhou, G.; Ewald, J.; Chang, L.; Hacariz, O.; Basu, N.; Xia, J. Using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 for LC-HRMS spectra processing, multi-omics integration and covariate adjustment of global metabolomics data. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 1735–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showpnil, I.A.; Selich-Anderson, J.; Taslim, C.; Boone, M.A.; Crow, J.C.; Theisen, E.R.; Lessnick, S.L. EWS/FLI mediated reprogramming of 3D chromatin promotes an altered transcriptional state in Ewing sarcoma. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 9814–9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Grullon, S.; Ge, K.; Peng, W. Spatial clustering for identification of ChIP-enriched regions (SICER) to map regions of histone methylation patterns in embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1150, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinz, S.; Benner, C.; Spann, N.; Bertolino, E.; Lin, Y.C.; Laslo, P.; Cheng, J.X.; Murre, C.; Singh, H.; Glass, C.K. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyioukos, C.; Bucchini, F.; Elati, M.; Képès, F. GREAT: A web portal for Genome Regulatory Architecture Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W77–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; He, Q.Y. ChIPseeker: An R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2382–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.; Dündar, F.; Diehl, S.; Grüning, B.A.; Manke, T. deepTools: A flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W187–W191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chang, H.; Kong, Y.; Ni, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Hou, M.; et al. Rescue of maternal immune activation-induced behavioral abnormalities in adult mouse offspring by pathogen-activated maternal Treg cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehati, A.; Abuduaini, B.; Liang, Z.; Chen, D.; He, F. Identification of heat shock protein family A member 5 (HSPA5) targets involved in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Genes Immun. 2023, 24, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Kim, M.; Hwang, S.W. Molecular mechanisms underlying the actions of arachidonic acid-derived prostaglandins on peripheral nociception. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, K.L.; Vorac, J.; Hofmann, K.; Meiser, P.; Unterweger, I.; Kuerschner, L.; Weighardt, H.; Förster, I.; Thiele, C. Kupffer Cells Sense Free Fatty Acids and Regulate Hepatic Lipid Metabolism in High-Fat Diet and Inflammation. Cells 2020, 9, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatrafi, M.M.; Vergara-Jimenez, M.; Murillo, A.G.; Norris, G.H.; Blesso, C.N.; Fernandez, M.L. Moringa Leaves Prevent Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Inflammation in Guinea Pigs by Reducing the Expression of Genes Involved in Lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fan, Y.; Tang, M.; Wu, X.; Bai, S.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, C.; Ji, C.; Wade, P.A.; et al. Bisphenol S Exposure and MASLD: A Mechanistic Study in Mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2025, 133, 57009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wu, L.; Yin, G.; Xie, X.; Kong, W.; Zhou, J.; Liu, S. C/EBPβ: The structure, regulation, and its roles in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 169, 115938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ling, X.; He, S.; Cui, H.; Yang, Z.; An, H.; Wang, L.; Zou, P.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. PPARα/ACOX1 as a novel target for hepatic lipid metabolism disorders induced by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: An integrated approach. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Zhang, D.H.; Jiang, L.D.; Qi, Y.; Guo, L.H. Binding and activity of bisphenol analogues to human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bai, S.; Wu, X.; Mao, W.; Guo, M.; Qin, Y.; Du, G. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Reprograms Offspring’s Immune–Metabolic Axis: A Multi-Omics Investigation of Intergenerational Hepatotoxicity. Toxics 2026, 14, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010097

Bai S, Wu X, Mao W, Guo M, Qin Y, Du G. Perinatal BPAF Exposure Reprograms Offspring’s Immune–Metabolic Axis: A Multi-Omics Investigation of Intergenerational Hepatotoxicity. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Shengjun, Xiaorong Wu, Wei Mao, Mengan Guo, Yufeng Qin, and Guizhen Du. 2026. "Perinatal BPAF Exposure Reprograms Offspring’s Immune–Metabolic Axis: A Multi-Omics Investigation of Intergenerational Hepatotoxicity" Toxics 14, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010097

APA StyleBai, S., Wu, X., Mao, W., Guo, M., Qin, Y., & Du, G. (2026). Perinatal BPAF Exposure Reprograms Offspring’s Immune–Metabolic Axis: A Multi-Omics Investigation of Intergenerational Hepatotoxicity. Toxics, 14(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010097