Unveiling the Metabolic Fingerprint of Occupational Exposure in Ceramic Manufactory Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. NMR Spectroscopy Experimental Settings

2.4. Spectral Preprocessing

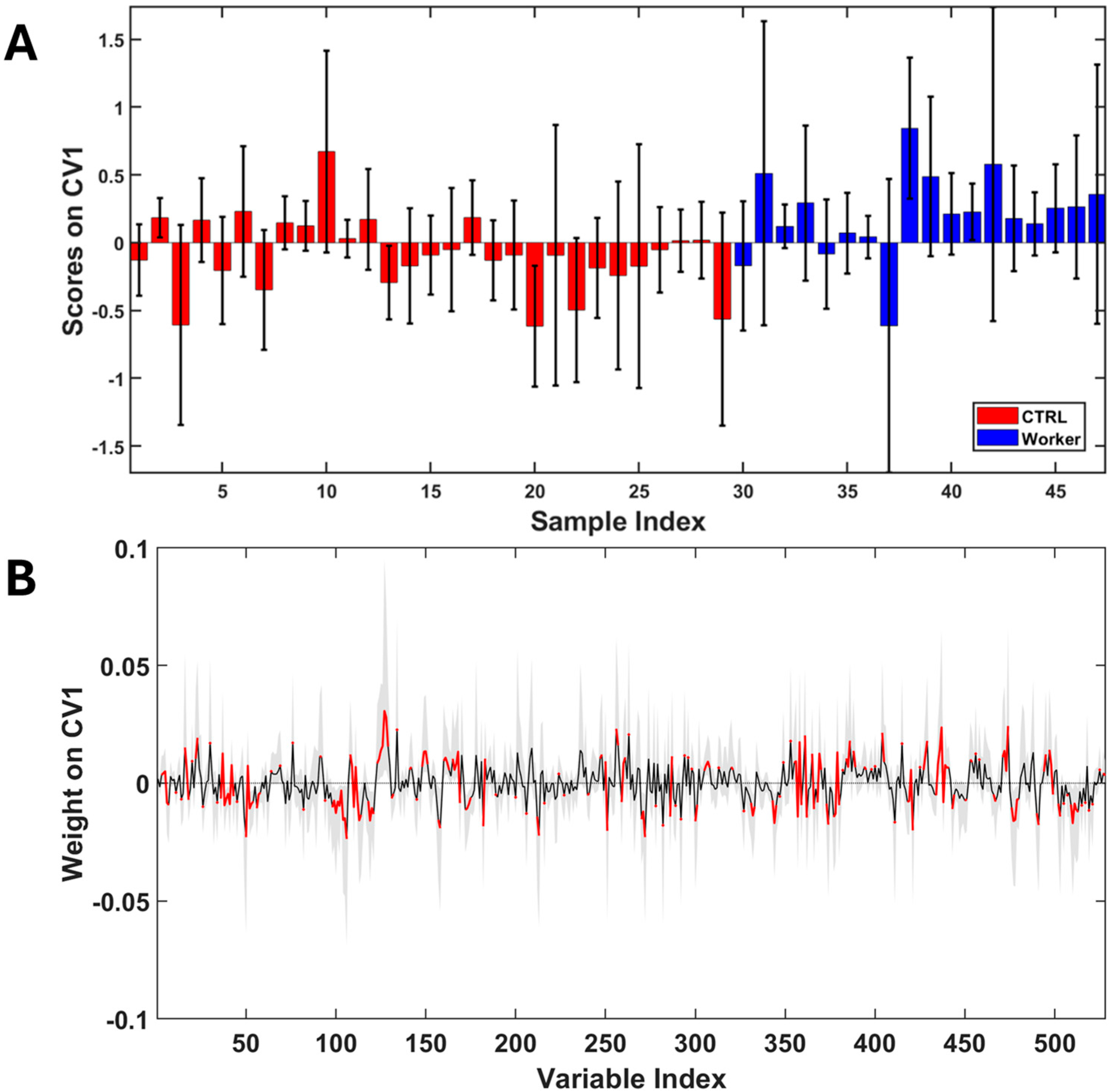

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Writer, S. The Italian Ceramic Industry Recorded Revenues of €8.7 Billion in 2022; FX Design: Orlando, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Winnette, R.; Banerjee, A.; Sikirica, V.; Peeva, E.; Wyrwich, K. Characterizing the Relationships between Patient-reported Outcomes and Clinician Assessments of Alopecia Areata in a Phase 2a Randomized Trial of Ritlecitinib and Brepocitinib. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, A.; Corfiati, M.; Marzio, D.D.; Iavicoli, S. Evaluation of Workplace Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica in Italy. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2014, 20, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemery, B. OCCUPATIONAL DISEASES|Overview. In Encyclopedia of Respiratory Medicine; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirtle, B.; Teschke, K.; van Netten, C.; Brauer, M. Kiln Emissions and Potters’ Exposures. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 1998, 59, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, E.; Brighenti, F.; Rossi, A.; Caroldi, S.; Gori, G.P.; Chiesura, P. The Ceramics Industry and Lead Poisoning. Lead Poisoning in Relation to Technology and Jobs. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1980, 6, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Lindon, J.C. Systems Biology: Metabonomics. Nature 2008, 455, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emwas, A.-H.; Roy, R.; McKay, R.T.; Tenori, L.; Saccenti, E.; Gowda, G.A.N.; Raftery, D.; Alahmari, F.; Jaremko, L.; Jaremko, M.; et al. NMR Spectroscopy for Metabolomics Research. Metabolites 2019, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckonert, O.; Keun, H.C.; Ebbels, T.M.D.; Bundy, J.; Holmes, E.; Lindon, J.C.; Nicholson, J.K. Metabolic Profiling, Metabolomic and Metabonomic Procedures for NMR Spectroscopy of Urine, Plasma, Serum and Tissue Extracts. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2692–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Giampaoli, O.; Patriarca, A.; Marini, F.; Pietroiusti, A.; Ippoliti, L.; Paolino, A.; Militello, A.; Fetoni, A.R.; Sisto, R.; et al. Urinary Metabolomics of Plastic Manufacturing Workers: A Pilot Study. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savorani, F.; Tomasi, G.; Engelsen, S.B. icoshift: A Versatile Tool for the Rapid Alignment of 1D NMR Spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 2010, 202, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, T.; Sinnaeve, D.; Van Gasse, B.; Tsiporkova, E.; Rietzschel, E.R.; De Buyzere, M.L.; Gillebert, T.C.; Bekaert, S.; Martins, J.C.; Van Criekinge, W. NMR-Based Characterization of Metabolic Alterations in Hypertension Using an Adaptive, Intelligent Binning Algorithm. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 3783–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMRB—Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank. Available online: https://bmrb.io/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Wishart, D.S.; Guo, A.; Oler, E.; Wang, F.; Anjum, A.; Peters, H.; Dizon, R.; Sayeeda, Z.; Tian, S.; Lee, B.L.; et al. HMDB 5.0: The Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D622–D631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuppi, C.; Messana, I.; Forni, F.; Rossi, C.; Pennacchietti, L.; Ferrari, F.; Giardina, B. 1H NMR Spectra of Normal Urines: Reference Ranges of the Major Metabolites. Clin. Chim. Acta 1997, 265, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, C.; Pibiri, M.; Leoni, V.P.; Cabras, F.; Restivo, A.; Griffin, J.L.; Fanos, V.; Mussap, M.; Zorcolo, L.; Atzori, L. Urinary 1H-NMR Metabolic Signature in Subjects Undergoing Colonoscopy for Colon Cancer Diagnosis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouatra, S.; Aziat, F.; Mandal, R.; Guo, A.C.; Wilson, M.; Knox, C.; Bjorndahl, T.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Saleem, F.; Liu, P.; et al. The Human Urine Metabolome. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, N.; Guevara-Morales, J.M.; Rodriguez-López, A.; Pulido, Á.; Díaz, J.; Edrada-Ebel, R.A.; Echeverri-Peña, O.Y. 1H-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Analysis of Urine as Diagnostic Tool for Organic Acidemias and Aminoacidopathies. Metabolites 2021, 11, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afanador, N.L.; Smolinska, A.; Tran, T.N.; Blanchet, L. Unsupervised Random Forest: A Tutorial with Case Studies. J. Chemom. 2016, 30, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Horvath, S. Unsupervised Learning with Random Forest Predictors. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2006, 15, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E.; Saccenti, E.; Smilde, A.K.; Westerhuis, J.A. Double-Check: Validation of Diagnostic Statistics for PLS-DA Models in Metabolomics Studies. Metabolomics 2012, 8, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy Metals: Toxicity and Human Health Effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, H.; Kamogashira, T.; Yamasoba, T. Heavy Metal Exposure: Molecular Pathways, Clinical Implications, and Protective Strategies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keunen, E.; Remans, T.; Bohler, S.; Vangronsveld, J.; Cuypers, A. Metal-Induced Oxidative Stress and Plant Mitochondria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 6894–6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaeva, E.A.; Sokolova, T.V.; Emelyanova, L.V.; Zakharova, I.O. Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Heavy Metal-Induced Neurotoxicity: Effects of Cadmium, Mercury, and Copper. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 136063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Högberg, J.; Adner, M.; Ramos-Ramírez, P.; Stenius, U.; Zheng, H. Crystalline Silica Particles Cause Rapid NLRP3-Dependent Mitochondrial Depolarization and DNA Damage in Airway Epithelial Cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Du, S.; Zhang, Z. The Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Macrophages on SiO2-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Abulikemu, A.; Lv, S.; Qi, Y.; Duan, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, R.; Guo, C.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z. Oxidative Stress- and Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Mediated Cytotoxicity by Silica Nanoparticle in Lung Epithelial Cells from Metabolomic Perspective. Chemosphere 2021, 275, 129969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wang, J.; Jing, L.; Ma, R.; Liu, X.; Gao, L.; Cao, L.; Duan, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Perturbations of Mitochondrial Dynamics and Biogenesis Involved in Endothelial Injury Induced by Silica Nanoparticles. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artana, I.G.N.B.; Artini, I.G.A.; Arijana, I.G.K.N.; Rai, I.B.N.; Indrayani, A.W. Exposure Time of Silica Dust and the Incidence of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Fibrosis in Rat Lungs. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 1378–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M.; Zare Sakhvid, M.J.; Bahrami, A.; Berijani, N.; Mahjub, H. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Exhaled Breath of Workers Exposed to Crystalline Silica Dust by SPME-GC-MS. J. Res. Health Sci. 2016, 16, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Anlar, H.G.; Bacanli, M.; İritaş, S.; Bal, C.; Kurt, T.; Tutkun, E.; Yilmaz, O.H.; Basaran, N. Effects of Occupational Silica Exposure on OXIDATIVE Stress and Immune System Parameters in Ceramic Workers in TURKEY. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2017, 80, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzgar, F.; Sadeghi-Mohammadi, S.; Aftabi, Y.; Zarredar, H.; Shakerkhatibi, M.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Gholampour, A. Oxidative Stress Indices Induced by Industrial and Urban PM2.5-Bound Metals in A549 Cells. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hoppe, T. Role of Amino Acid Metabolism in Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1127618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, P.K.; Finley, L.W.S. Regulation and Function of the Mammalian Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, L.J.; Schultz, K.; Massey, W.; DeLucia, B.; Choucair, I.; Varadharajan, V.; Banerjee, R.; Fung, K.; Horak, A.J.; Orabi, D.; et al. A Gut Microbial Metabolite of Dietary Polyphenols Reverses Obesity-Driven Hepatic Steatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2202934119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dwidar, M.; Nemet, I.; Buffa, J.A.; Sangwan, N.; Li, X.S.; Anderson, J.T.; Romano, K.A.; Fu, X.; Funabashi, M.; et al. Two Distinct Gut Microbial Pathways Contribute to Meta-Organismal Production of Phenylacetylglutamine with Links to Cardiovascular Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 18–32.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-T.; Huang, S.-Q.; Lin, C.-H.; Pao, L.-H.; Chiu, C.-H. Quantification of Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis-Related Organic Acids in Human Urine Using LC-MS/MS. Molecules 2022, 27, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruss, K.M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Van Treuren, W.; Higginbottom, S.K.; Jarman, J.B.; Fischer, C.R.; Mak, J.; Wong, B.; Cowan, T.M.; et al. Host-Microbe Co-Metabolism via MCAD Generates Circulating Metabolites Including Hippuric Acid. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, I.; Saha, P.P.; Gupta, N.; Zhu, W.; Romano, K.A.; Skye, S.M.; Cajka, T.; Mohan, M.L.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. A Cardiovascular Disease-Linked Gut Microbial Metabolite Acts via Adrenergic Receptors. Cell 2020, 180, 862–877.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (mean ± SD) | Males (N) | Females (N) | Smokers (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| workers | 48 ± 10 | 7 | 11 | 6 |

| CTRLS | 55 ± 7 | 8 | 21 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

De Rosa, M.; Canepari, S.; Tranfo, G.; Giampaoli, O.; Patriarca, A.; Smolinska, A.; Marini, F.; Massimi, L.; Sciubba, F.; Spagnoli, M. Unveiling the Metabolic Fingerprint of Occupational Exposure in Ceramic Manufactory Workers. Toxics 2026, 14, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010056

De Rosa M, Canepari S, Tranfo G, Giampaoli O, Patriarca A, Smolinska A, Marini F, Massimi L, Sciubba F, Spagnoli M. Unveiling the Metabolic Fingerprint of Occupational Exposure in Ceramic Manufactory Workers. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Rosa, Michele, Silvia Canepari, Giovanna Tranfo, Ottavia Giampaoli, Adriano Patriarca, Agnieszka Smolinska, Federico Marini, Lorenzo Massimi, Fabio Sciubba, and Mariangela Spagnoli. 2026. "Unveiling the Metabolic Fingerprint of Occupational Exposure in Ceramic Manufactory Workers" Toxics 14, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010056

APA StyleDe Rosa, M., Canepari, S., Tranfo, G., Giampaoli, O., Patriarca, A., Smolinska, A., Marini, F., Massimi, L., Sciubba, F., & Spagnoli, M. (2026). Unveiling the Metabolic Fingerprint of Occupational Exposure in Ceramic Manufactory Workers. Toxics, 14(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010056