Age-Dependent Effects of Heavy Metals on the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Testicular Axis-Related Hormones in Men

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Assessment of Metal Exposure

2.3. Measurement of Hormones, Vitamin D, and Folate

2.4. Assessments of Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Distribution of Hormones Across Age Groups

3.3. Association Between Individual Heavy Metals and Hormones

3.4. Mixture Effects of Metal Exposure

3.5. Modifying Effects

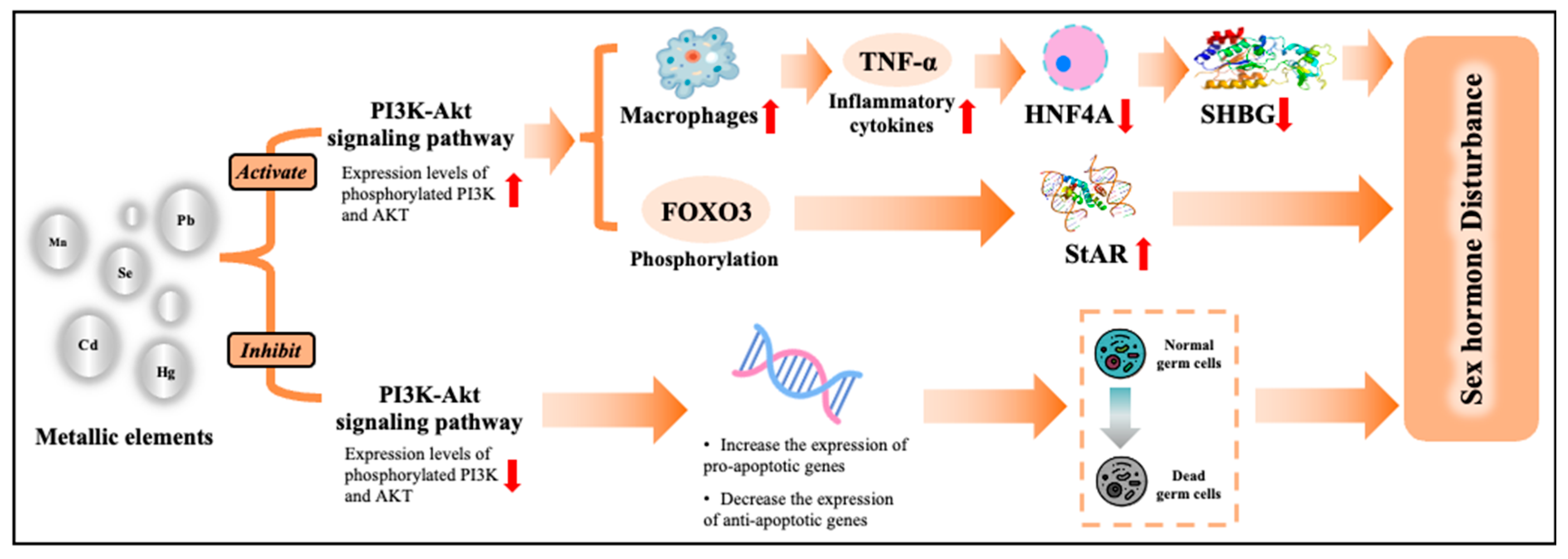

3.6. Biological Pathway of Metals on HPT Axis-Related Hormones

3.7. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zoroddu, M.A.; Aaseth, J.; Crisponi, G.; Medici, S.; Peana, M.; Nurchi, V.M. The essential metals for humans: A brief overview. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 195, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayman, M.P. Selenium and human health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: Toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu Ohiagu, F.; Chikezie, P.C.; Ahaneku, C.C.; Chikezie, C.M. Human exposure to heavy metals: Toxicity mechanisms and health implications. Mater. Sci. Eng. Int. J. 2022, 6, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soisungwan, S.; David, A.V.; Aleksandra Buha, Đ. The NOAEL equivalent for the cumulative body burden of cadmium: Focus on proteinuria as an endpoint. J. Environ. Expo. Assess. 2024, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shi, Q.; Liu, C.; Sun, Q.; Zeng, X. Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Heavy Metals on Human Health. Toxics 2023, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, Y.; Ebrahimpour, K.; Maghami, M.; Shoshtari-Yeganeh, B.; Kelishadi, R. The Association Between Heavy Metals Exposure and Sex Hormones: A Systematic Review on Current Evidence. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 3491–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassotis, C.D.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Demeneix, B.A.; Porta, M.; Slama, R.; Trasande, L. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Economic, regulatory, and policy implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starka, L.; Duskova, M. What is a hormone? Physiol. Res. 2020, 69, S183–S185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, H. Endocrine System. In Fundamentals of Medicine for Biomedical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 409–433. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, A.A.; Quinton, R. Anatomy and Physiology of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis. In Advanced Practice in Endocrinology Nursing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 839–852. [Google Scholar]

- Corradi, P.F.; Corradi, R.B.; Greene, L.W. Physiology of the Hypothalamic Pituitary Gonadal Axis in the Male. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 43, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature Reviews Disease Primers. Male infertility. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Singh, A.K. Impact of environmental factors on human semen quality and male fertility: A narrative review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, C. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Its Regulation. In The Peripheral Existence and Effects of Corticotropin-releasing Factor Family; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiydzenyuy, N.E.; Qulu, L.A. Stress, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, and aggression. Metab. Brain Dis. 2024, 39, 1613–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightman, S.L.; Birnie, M.T.; Conway-Campbell, B.L. Dynamics of ACTH and Cortisol Secretion and Implications for Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, bnaa002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honour, J.W. 17-Hydroxyprogesterone in children, adolescents and adults. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 51, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, J.D.; Rossano, M.G.; Protas, B.; Padmanahban, V.; Diamond, M.P.; Puscheck, E.; Daly, D.; Paneth, N.; Wirth, J.J. Environmental exposure to metals and male reproductive hormones: Circulating testosterone is inversely associated with blood molybdenum. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, J.J.; Mijal, R.S. Adverse effects of low level heavy metal exposure on male reproductive function. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2010, 56, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, S.; Fan, F.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Association of blood metals with serum sex hormones in adults: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 69628–69638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Weiler, H.A.; Kuiper, J.R.; Borghese, M.; Buckley, J.P.; Shutt, R.; Ashley-Martin, J.; Subramanian, A.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Potter, B.K.; et al. Vitamin D and Toxic Metals in Pregnancy—A Biological Perspective. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2024, 11, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Tong, M. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D mediates the association between heavy metal exposure and cardiovascular disease. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Chen, W.J.; Lee, H.L.; Lin, Y.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Shiue, H.S.; Pu, Y.S.; Hsueh, Y.M. Possible Combined Effects of Plasma Folate Levels, Global DNA Methylation, and Blood Cadmium Concentrations on Renal Cell Carcinoma. Nutrients 2023, 15, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Y.; Li, A.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Feng, G. Exposure to Aldehydes, Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines and Terpenes With Sex Hormones in U.S. Children and Adolescents: Sex-, Age-Dependent Patterns and Vitamin D Effect Modification. Phenomics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCHS. NHANES August 2021–August 2023 Laboratory Methods. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/labmethods.aspx?Cycle=2021-2023 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Mei, Y.; Liu, J.; Dong, Z.; Ke, S.; Su, W.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Wu, J.; et al. Heavy metals exposure and HPG-axis related hormones in women across the lifespan: An integrative epidemiological and bioinformatic perspective. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 303, 118962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Mei, Y.; Zhao, M.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ge, X.; Xu, Q. Do urinary metals associate with the homeostasis of inflammatory mediators? Results from the perspective of inflammatory signaling in middle-aged and older adults. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, A.P.; Buckley, J.P.; O’Brien, K.M.; Ferguson, K.K.; Zhao, S.; White, A.J. A Quantile-Based g-Computation Approach to Addressing the Effects of Exposure Mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 47004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, S.; Brook, R.D.; Feng, B.; Zhao, Q.; Song, X.; Yi, T.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Extreme Levels of Air Pollution Associated With Changes in Biomarkers of Atherosclerotic Plaque Vulnerability and Thrombogenicity in Healthy Adults. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, e30–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakkebaek, N.E.; Rajpert-De Meyts, E.; Buck Louis, G.M.; Toppari, J.; Andersson, A.M.; Eisenberg, M.L.; Jensen, T.K.; Jorgensen, N.; Swan, S.H.; Sapra, K.J.; et al. Male Reproductive Disorders and Fertility Trends: Influences of Environment and Genetic Susceptibility. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 55–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, P. Environmental and occupational exposure of metals and their role in male reproductive functions. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 36, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yuan, G.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Y.; Wen, Y.; Huang, S.; Ke, Y.; et al. The association between metal exposure and semen quality in Chinese males: The mediating effect of androgens. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 113975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, Z.; Zhang, G.; Ling, X.; Dong, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, P.; Yang, H.; Zhou, N.; Chen, Q.; et al. Low-level and combined exposure to environmental metal elements affects male reproductive outcomes: Prospective MARHCS study in population of college students in Chongqing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, F.; Qi, Z.; Xu, B.; Liu, W.; Deng, Y. Occupational manganese exposure, reproductive hormones, and semen quality in male workers: A cross-sectional study. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2019, 35, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiri-Hanninen, T.; Sankilampi, U.; Dunkel, L. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in infancy: Minipuberty. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2014, 82, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillon, R.; Marcocci, C.; Carmeliet, G.; Bikle, D.; White, J.H.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Lips, P.; Munns, C.F.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Giustina, A.; et al. Skeletal and Extraskeletal Actions of Vitamin D: Current Evidence and Outstanding Questions. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1109–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa Younis Gaballah, Y. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Libya and its relation to other health disorders. Metab. Target Organ Damage 2024, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, T.E.; Liang, C.L.; Morisset, A.S.; Fisher, M.; Weiler, H.; Cirtiu, C.M.; Legrand, M.; Davis, K.; Ettinger, A.S.; Fraser, W.D.; et al. Maternal and fetal exposure to cadmium, lead, manganese and mercury: The MIREC study. Chemosphere 2016, 163, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducker, G.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascari, M.; Reeves, K.; Balasubramanian, R.; Liu, Z.; Laouali, N.; Oulhote, Y. Associations of Environmental Pollutant Mixtures and Red Blood Cell Folate Concentrations: A Mixture Analysis of the U.S. Adult Population Based on NHANES Data, 2007–2016. Toxics 2025, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceau, K.; Ruttle, P.L.; Shirtcliff, E.A.; Essex, M.J.; Susman, E.J. Developmental and contextual considerations for adrenal and gonadal hormone functioning during adolescence: Implications for adolescent mental health. Dev. Psychobiol. 2015, 57, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Craemer, S.; Croes, K.; van Larebeke, N.; De Henauw, S.; Schoeters, G.; Govarts, E.; Loots, I.; Nawrot, T.; Nelen, V.; Den Hond, E.; et al. Metals, hormones and sexual maturation in Flemish adolescents in three cross-sectional studies (2002–2015). Environ. Int. 2017, 102, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwalba, A.; Orlowska, J.; Slota, M.; Jeziorska, M.; Filipecka, K.; Bellanti, F.; Dobrakowski, M.; Kasperczyk, A.; Zalejska-Fiolka, J.; Kasperczyk, S. Effect of Cadmium on Oxidative Stress Indices and Vitamin D Concentrations in Children. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenod, F.; Lee, W.K.; Garrick, M.D. Iron and Cadmium Entry Into Renal Mitochondria: Physiological and Toxicological Implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaml-Sorensen, A.; Brix, N.; Lunddorf, L.L.H.; Ernst, A.; Hoyer, B.B.; Olsen, S.F.; Granstrom, C.; Toft, G.; Henriksen, T.B.; Ramlau-Hansen, C.H. Maternal intake of folate and folic acid during pregnancy and pubertal timing in girls and boys: A population-based cohort study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2023, 37, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakaratne, R.; Lin, P.D.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Wright, R.O.; Hubbard, A.; Hivert, M.F.; Bellinger, D.; Oken, E.; Cardenas, A. Mixtures of Metals and Micronutrients in Early Pregnancy and Cognition in Early and Mid-Childhood: Findings from the Project Viva Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 87008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.A.; Hafez, H.A.; Kamel, M.A.; Ghamry, H.I.; Shukry, M.; Farag, M.A. Dietary Vitamin B Complex: Orchestration in Human Nutrition throughout Life with Sex Differences. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomberg Jensen, M. Vitamin D metabolism, sex hormones, and male reproductive function. Reproduction 2012, 144, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Beld, A.W.; Kaufman, J.M.; Zillikens, M.C.; Lamberts, S.W.J.; Egan, J.M.; van der Lely, A.J. The physiology of endocrine systems with ageing. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frungieri, M.B.; Calandra, R.S.; Bartke, A.; Matzkin, M.E. Male and female gonadal ageing: Its impact on health span and life span. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 197, 111519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Qin, N.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, B.; Liao, Y.; Zeng, H.; Cheng, L.; et al. Multi-metal mixture exposure and cognitive function in urban older adults: The mediation effects of thyroid hormones. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Manousaki, D.; Rosen, C.; Trajanoska, K.; Rivadeneira, F.; Richards, J.B. The health effects of vitamin D supplementation: Evidence from human studies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyer, N.; Gueant-Rodriguez, R.M.; Agopiantz, M.; Leininger-Muller, B. Steroids and one-carbon metabolism: Clinical implications in endocrine disorders. Neuroendocrinology 2025, 115, 875–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, A.; Cai, X.; Yu, A.; Xu, Q.; Wang, P.; Yao, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W. Arsenic exposure diminishes ovarian follicular reserve and induces abnormal steroidogenesis by DNA methylation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 241, 113816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, N.; Xu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Yao, G.; Tian, H.; Wang, G.; Lian, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F. Steroidogenic factor-1 is required for TGF-beta3-mediated 17beta-estradiol synthesis in mouse ovarian granulosa cells. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3213–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmer, B.P.; White, P.C. Minireview: Steroidogenic factor 1: Its roles in differentiation, development, and disease. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 1322–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Morales, P.; Saceda, M.; Kenney, N.; Kim, N.; Salomon, D.S.; Gottardis, M.M.; Solomon, H.B.; Sholler, P.F.; Jordan, V.C.; Martin, M.B. Effect of cadmium on estrogen receptor levels and estrogen-induced responses in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 16896–16901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticker, L.S.; Thompson, D.L., Jr.; Gentry, L.R. Pituitary hormone and insulin responses to infusion of amino acids and N-methyl-D,L-aspartate in horses. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 79, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Fukuda, A.; Nabekura, J. The role of GABA in the regulation of GnRH neurons. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, N.; Zhai, H.; Nie, X.; Sun, H.; Han, B.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Xia, F.; et al. Associations of blood lead levels with reproductive hormone levels in men and postmenopausal women: Results from the SPECT-China Study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.H.; Glass, T.A.; Bressler, J.; Todd, A.C.; Schwartz, B.S. Blood lead is a predictor of homocysteine levels in a population-based study of older adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ding, N.; Harlow, S.D.; Randolph, J.F., Jr.; Mukherjee, B.; Gold, E.B.; Park, S.K. Exposure to heavy metals and hormone levels in midlife women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriem, K.M.; Fathi, G.E.; Salem, H.A.; Akram, N.H.; Gamil, S.A. Protective role of pectin against cadmium-induced testicular toxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2013, 23, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknafs, B.; Salehnia, M.; Kamkar, M. Induction and determination of apoptotic and necrotic cell death by cadmium chloride in testis tissue of mouse. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2015, 16, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pan, K.; Tu, R.; Cai, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C. Association of blood lead with estradiol and sex hormone-binding globulin in 8-19-year-old children and adolescents. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1096659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszowski, T.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Gutowska, I.; Chlubek, D. Pro-inflammatory properties of cadmium. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2012, 59, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacino, J.A.; Arthur, A.E.; Ferguson, K.K.; Rozek, L.S. Dietary antioxidant and anti-inflammatory intake modifies the effect of cadmium exposure on markers of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress. Environ. Res. 2014, 131, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simó, R.; Barbosa-Desongles, A.; Lecube, A.; Hernandez, C.; Selva, D.M. Potential role of tumor necrosis factor-α in downregulating sex hormone-binding globulin. Diabetes 2012, 61, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Yang, J.; Cai, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Bao, J.; Zhang, Z. Cadmium induces apoptosis and autophagy in swine small intestine by downregulating the PI3K/Akt pathway. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 41207–41218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, H. Cadmium exposure activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway through miRNA-21, induces an increase in M1 polarization of macrophages, and leads to fibrosis of pig liver tissue. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 113015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Song, J.E.; Kong, B.S.; Hong, J.W.; Novelli, S.; Lee, E.J. The Role of Foxo3 in Leydig Cells. Yonsei Med. J. 2015, 56, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | All | Subgroups (Years Old) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3, 12) | [12, 20) | [20, 50) | [50, 80] | |||

| No. | 6547 | 824 | 1044 | 1924 | 2755 | - |

| Age, years | 42 (18, 62) | 8 (7, 10) | 15 (14, 17) | 35 (28, 42) | 65 (59, 72) | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.8 (22.6, 31.4) | 17.3 (15.7, 20.8) | 23.0 (19.7, 27.0) | 28.2 (24.8, 33.0) | 28.6 (25.4, 32.6) | <0.0001 |

| Education level | 0.001 | |||||

| High school or below | 1805 (38.58%) | - | - | 687 (35.71%) | 1118 (40.58%) | |

| Some college or AA | 1414 (30.22%) | - | - | 629 (32.69%) | 785 (28.49%) | |

| College graduate or above | 1460 (31.20%) | - | - | 608 (31.60%) | 852 (30.93%) | |

| Race | <0.0001 | |||||

| Hispanic | 1366 (20.86%) | 208 (25.24%) | 272 (26.05%) | 443 (23.02%) | 443 (16.08%) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 3008 (45.94%) | 313 (37.99%) | 391 (37.45%) | 822 (42.72%) | 1482 (53.79%) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1206 (18.42%) | 175 (21.24%) | 196 (18.77%) | 337 (17.52%) | 498 (18.08%) | |

| Others | 967 (14.77%) | 128 (15.53%) | 185 (17.72%) | 322 (16.74%) | 332 (12.05%) | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | |||||

| Married/with Partner | 2937 (62.77%) | - | - | 1140 (59.25%) | 1797 (65.23%) | |

| Separated/Never married | 1742 (37.23%) | - | - | 784 (40.75%) | 958 (34.77%) | |

| Examined time | <0.0001 | |||||

| Morning | 3248 (49.61%) | 347 (42.11%) | 466 (44.64%) | 989 (51.40%) | 1446 (52.49%) | |

| Afternoon/evening | 3299 (50.39%) | 477 (57.89%) | 578 (55.36%) | 935 (48.60%) | 1309 (47.51%) | |

| Smoke habit | <0.0001 | |||||

| Never | 2345 (50.12%) | - | - | 1105 (57.43%) | 1240 (45.01%) | |

| Current | 1452 (31.03%) | - | - | 387 (20.11%) | 1065 (38.66%) | |

| Former | 882 (18.85%) | - | - | 432 (22.45%) | 450 (16.33%) | |

| Drink habit | <0.0001 | |||||

| Never | 286 (6.11%) | - | - | 114 (5.93%) | 172 (6.24%) | |

| Current | 856 (18.29%) | - | - | 198 (10.29%) | 658 (23.88%) | |

| Former | 3537 (75.59%) | - | - | 1612 (83.78%) | 1925 (69.87%) | |

| PIR | 2.5 (1.3, 4.6) | 1.8 (0.9, 3.6) | 1.8 (0.9, 3.6) | 2.8 (1.4, 5.0) | 2.8 (1.5, 5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Cadmium, μg/L | 0.18 (0.11, 0.34) | 0.08 (0.07, 0.12) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.17) | 0.18 (0.12, 0.35) | 0.28 (0.18, 0.49) | <0.0001 |

| Lead, μg/dL | 0.75 (0.46, 1.26) | 0.46 (0.33, 0.65) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.58) | 0.69 (0.47, 1.06) | 1.13 (0.77, 1.71) | <0.0001 |

| Mercury, μg/L | 0.47 (0.20, 1.13) | 0.20 (0.18, 0.37) | 0.21 (0.20, 0.54) | 0.56 (0.22, 1.28) | 0.70 (0.31, 1.55) | <0.0001 |

| Manganese, μg/L | 8.73 (7.10, 10.82) | 9.78 (8.01, 12.08) | 9.65 (7.93, 11.65) | 8.47 (6.96, 10.36) | 8.31 (6.71, 10.34) | <0.0001 |

| Selenium, μg/L | 180.25 (165.75, 196.59) | 165.28 (154.1, 178.87) | 179.34 (166.78, 193.32) | 184.55 (170.95, 199.70) | 182.08 (167.2, 198.87) | <0.0001 |

| Sex Hormones | Children | Adolescents | Young Adults | Older Adults |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST | Cd (+) | Hg (+) | Cd (+) | |

| EST | Cd (+); Se (~) | Cd (+); Mn (+) | ||

| SHBG | Mn (−); Se (−) | Cd (+); Se (−) | Cd(~); Pb(~); Se(~) | |

| 17H | Se (+) | |||

| AND | Cd (+) | Mn (+) | ||

| AMH | ||||

| ESO | Pb (−) | Cd (+) | Cd(+); Pb(+); Mn(+); Se (−) | |

| ES1 | Pb (~) | Se (+) | ||

| FSH | Mn (+) | Hg (~) | ||

| LH | Cd (+) | Pb (+) | ||

| PG4 | Se (+); Hg (+) | Pb (+) | ||

| DHE | Se (+) | Hg (+) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license).

Share and Cite

Mei, Y.; Yan, Y.; Ke, S.; Su, W.; Luo, Z.; Chen, X.; Xu, H.; Su, W.; Li, A. Age-Dependent Effects of Heavy Metals on the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Testicular Axis-Related Hormones in Men. Toxics 2026, 14, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010055

Mei Y, Yan Y, Ke S, Su W, Luo Z, Chen X, Xu H, Su W, Li A. Age-Dependent Effects of Heavy Metals on the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Testicular Axis-Related Hormones in Men. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleMei, Yayuan, Yongfu Yan, Shenglan Ke, Weihui Su, Zhangjia Luo, Xiaobao Chen, Hui Xu, Weitao Su, and Ang Li. 2026. "Age-Dependent Effects of Heavy Metals on the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Testicular Axis-Related Hormones in Men" Toxics 14, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010055

APA StyleMei, Y., Yan, Y., Ke, S., Su, W., Luo, Z., Chen, X., Xu, H., Su, W., & Li, A. (2026). Age-Dependent Effects of Heavy Metals on the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Testicular Axis-Related Hormones in Men. Toxics, 14(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010055