Physiological Responses of Serratia marcescens to Magnetic Biochars and Coexisting Microplastics and the Relationships with Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of Magnetic Biochars

2.3. Experiment on Effects of MBCs and PBAT MPs on Physiology of Serratia marcescens ZY01

2.3.1. Culture Treatments of Serratia marcescens ZY01

2.3.2. Determination of Physiological Indicators of Serratia marcescens ZY01

2.4. Soil Incubation and Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlations Between Serratia and tet Gene in Soil

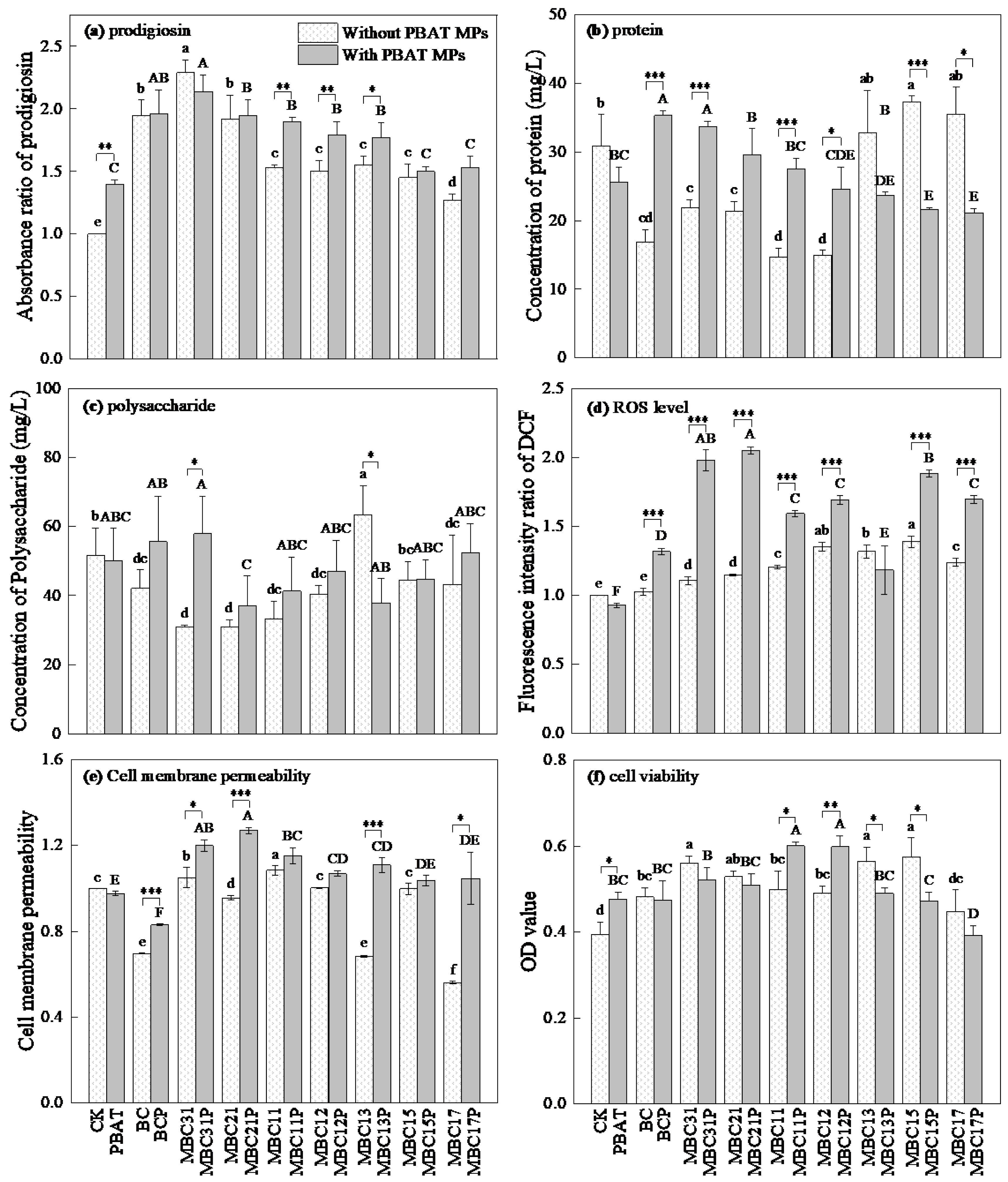

3.2. Effects of BC/MBCs and PBAT MPs on Physiological Characteristics of Serratia marcescens ZY01

3.3. Effects of the Changes in Physiological Characteristics of Serratia marcescens ZY01 on Serratia and tet Gene Abundances in Soil

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Shen, H.; Wei, M.; Gu, L.; Liu, Q. Genomic evolution, antimicrobial resistance, and dissemination of global Serratia spp. unveil increasing species diveristy and carbapenemae-resistance: A retrospective and genomic epidemiology study. Cur. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100456. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wang, D.; Gao, S.; Zhou, W.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, X. A comprehensive analysis of the epidemiological and genomic characteristics of global Serratia Marcescens. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 40, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, C.; Hu, X.; Ma, S.; Zou, J.; Lin, R.; Hou, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, N. Distribution of and associations between ARGs and pathogenic bacteria in soils affected by heavy metal contamination in mining areas. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, D.; Ji, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, F.; Zou, C. The combined effect of microplastics and tetracycline on soil microbial communities and ARGs. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 378, 126482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, J.; Peng, S.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, S. Biodegradable microplastics exacerbate the risk of antibiotic resistance genes pollution in agricultural soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ren, R.; Yan, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y. Effects of microplastics on dissipation of oxytetracycline and its relevant resistance genes in soil without and with Serratia marcescens: Comparison between biodegradable and conventional microplastics. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2024, 287, 117235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, P.; Zhang, H.; Shen, X. Deciphering the mobility and bacterial hosts of antibiotic resistance genes under the coexistence of antibiotics and microplastics by metagenomic analysis and binning method. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. The combination of polystyrene microplastics and di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate promotes the conjugative transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between bacteria. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2025, 289, 117681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Shao, M.; Wei, Z.M.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Luo, X.; Li, F.; et al. Microplastics enhance the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in mariculture sediments by enriching host bacteria and promoting horizontal gene transfer. Eco-Environ. Health 2025, 4, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yuan, X.; Lu, W.; Wen, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, T. Microplastics in livestock manure and compost: Environmental distribution, degradation behavior, and their impact on antibiotic resistance gene dissemination. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, N.; Bo, J.; Meng, X.; Chen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, W. Microplastic biofilms promote the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in estuarine environments. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 202, 106777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavitha, B.; Reddy, P.V.L.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.S.; Pandey, S.K.; Kim, K.-H. Benefits and limitations of biochar amendment in agricultural soils: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 227, 146−154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Su, P.; Tang, M.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, G. Meta-analysis reveals the processes and conditions of using biochar to control antibiotic resistance genes in soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 386, 125736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Jia, W.-L.; Ma, R.; Yu, Y.-H.; Qiao, L.-K.; Gao, F.-Z.; Ying, G.-G. Differential regulation of soil antibiotic resistance genes by biochar types and their derived dissolved organic matter. Soil Environ. Health 2025, 3, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, K.; Liu, C. Co-exposure of pyraclostrobin and biochar promoted antibiotic resistance genes transfer from soil to lettuce. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Feng, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, Z.; Peng, T.; Yan, C.; Song, B. When biochar meets iron mineral: An opportunity to achieve enhanced performance in treating toxic metal(loid)s and regractory organics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 350, 128022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yao, J.; Yue, T.; Liu, L.; Sun, C.; Cai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shao, M.; Wu, J.; Luo, X.; et al. Inactivation of antibiotic resistance genes by nanoscale zero-valent iron modified biochar composites: Synergistic effect of oxidative damage and physical destruction. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cai, S.; Xu, M. Nanoscale zero-valent iron alleviated horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in soil: The important role of extracellular polymeric substances. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wu, X.; He, C.; Zhang, J.; Hou, J.; Lin, D. nZVI-induced iron poisoning aggravated the toxicity of TCEP to earthworm in soil. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, R.; Chang, H.; Zhong, N.; Zhang, T.; Wang, K.; Ren, N.; Ho, S.-H. Rational electron tuning of magnetic biochar via N,S co-doping for intense tetracycline degradation: Efficiency improvement and toxicity alleviation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458, 141470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ren, R.; Yan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, G. The key role of magnetic iron-to-biochar mass ratios in the dissipation of oxytetracycline and its resistance genes in soils with and without biodegradable microplastics. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, S.; Zhao, J. Enhanced removal of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes by three-dimensional electrochemical process using MgFe2O4-loaded biochar as both particle electrode and catalyst for peroxymonosulfate activation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Fang, H.H. Tetracycline resistance genes and tetracycline resistance lactose-fermenting Enterobacteriaceae in activated sludge of sewage treatment plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 3455−3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Yang, L.; Chen, H.; Yan, Y.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z. Natural prodigiosin from Serratia marcescens: A promising functional food colorant with iron chelation and antioxidative properties. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Wu, H.; Li, W.; Ji, W.; Yin, B.; Sun, L.; Chen, L. Microbial reductive dehalogenation accelerated by muti-pathway electron transfer: The mediating role of novel multivalent iron-modified biochar redox mediators. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 531, 146860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani, A.C.B.; de Souza, J.C.; Furlan, J.P.R.; Stehling, E.G.; de Andrade, A.R.; Reginatto, V. A conductive film produced by the supernatant from Serratia marcescens cultivation containing prodigiosin increases electricity generation in a microbial fuel cell. Cur. Res. Biotechnol. 2024, 7, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Deng, H.; Mehta, N.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, D. Pyrolysis temperature dependent electron mediating mechanisms of biochar for microbial reduction of Fe(III)-rich smectite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 276, 107960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Liang, D.; He, W.; Lin, N.; Li, J. Magnetic biochar-mediated iron reduction synergizes with microbial co-metabolism for enhanced adsorption and in-situ degradation of sulfamethoxazole. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Han, Y.; Xu, H. Adaptive laboratory evolution of Serratia marcescens with enhanced osmotic stress tolerance for prodigiosin synthesis. Process Biochem. 2025, 148, 32−42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Tan, W.; Xie, L.; Ma, C.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Y. Mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effects of Cd2+ on prodigiosin synthesis in Serratia marcescens KMR-3. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2022, 236, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Cui, Z.; Li, N.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, C. Effects of polyethylene microplastics on cell membranes: A combined study of experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, M.; Xiao, K.; Gao, D. Elevating anaerobic digestion efficiency: Unveiling the alchemical effects of conductive materials on extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) composition. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, T.; Kappler, A.; Jiang, J. Biochar facilitates ferrihydrite reduction by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 through stimulating the secretion of extracellular polymeric substances. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Dai, Q.; Piao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. The group-modified nanoplastics bring higher risk on promoting the antibiotic resistance genes dissemination by stimulate bacteria to generate more ROS under aerobic condition. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Lyu, H.; Zhang, H.; Shen, B.; Tang, J. Active iron density and structure of iron ore crystal surface drive the generation of ROS and regulate the heterogeneous aggregation behavior of microplastics. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 510, 161467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Lee, H.-S.; Amarakoon, D.; Smolensky, D. Effect of polystyrene microplastics on tube formation and viability of endothelial cells. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2021, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X. Degradation Efficiency and Mechanism of Sulfamethoxazole by Serratia Biofilm-Colonized Microplastics. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhou, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, B.; Li, L. Combination of biochar and immobilized bacteria accelerates polyacrylamide biodegradation in soil by both bio-augmentation and bio-stimulation strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 405, 124086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, A.; Wen, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, Q. The fates of antibiotic resistance genes and their association with cell membrane permeability in response to peroxydisulfate during compositing. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Zhou, Z.-J.; Wen, H.-Q.; Chen, F.-F.; Pan, Y.; Tang, Q.; Yu, H.-Q. Deciphering the role of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in shaping disinfection kinetics through permanent removal via genetic disruption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 6552−6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Duan, G.; Xi, Y.; Chu, Y.; Li, F.; Ho, S.-H. Insights into the role of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in the spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, C.; Chu, C.; Zhu, X.; Chen, B. Biochar effectively inhibits the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes via restraining the energy supply for conjugative plasmid transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 12573−12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, P.; Jia, H. Microplastics exacerbated conjugative transfer of antibiotic resistance genes during ultraviolet disinfection: Highlighting difference between conventional and biodegradable ones. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 834−845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Lu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Guo, H.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Wang, T. Water temperature disturbance alters the conjugate transfer of antibiotic resistance genes via affecting ROS content and intercellular aggregation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Ren, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ping, L. Physiological Responses of Serratia marcescens to Magnetic Biochars and Coexisting Microplastics and the Relationships with Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Toxics 2026, 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010035

Zhang G, Ren R, Zhang X, Zhu Y, Li Y, Ping L. Physiological Responses of Serratia marcescens to Magnetic Biochars and Coexisting Microplastics and the Relationships with Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guixiang, Rui Ren, Xiaohui Zhang, Yuen Zhu, Yanxia Li, and Long Ping. 2026. "Physiological Responses of Serratia marcescens to Magnetic Biochars and Coexisting Microplastics and the Relationships with Antibiotic Resistance Genes" Toxics 14, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010035

APA StyleZhang, G., Ren, R., Zhang, X., Zhu, Y., Li, Y., & Ping, L. (2026). Physiological Responses of Serratia marcescens to Magnetic Biochars and Coexisting Microplastics and the Relationships with Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Toxics, 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010035