Molecular Mechanisms of Root Exudate-Mediated Remediation in Soils Co-Contaminated with Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Abstract

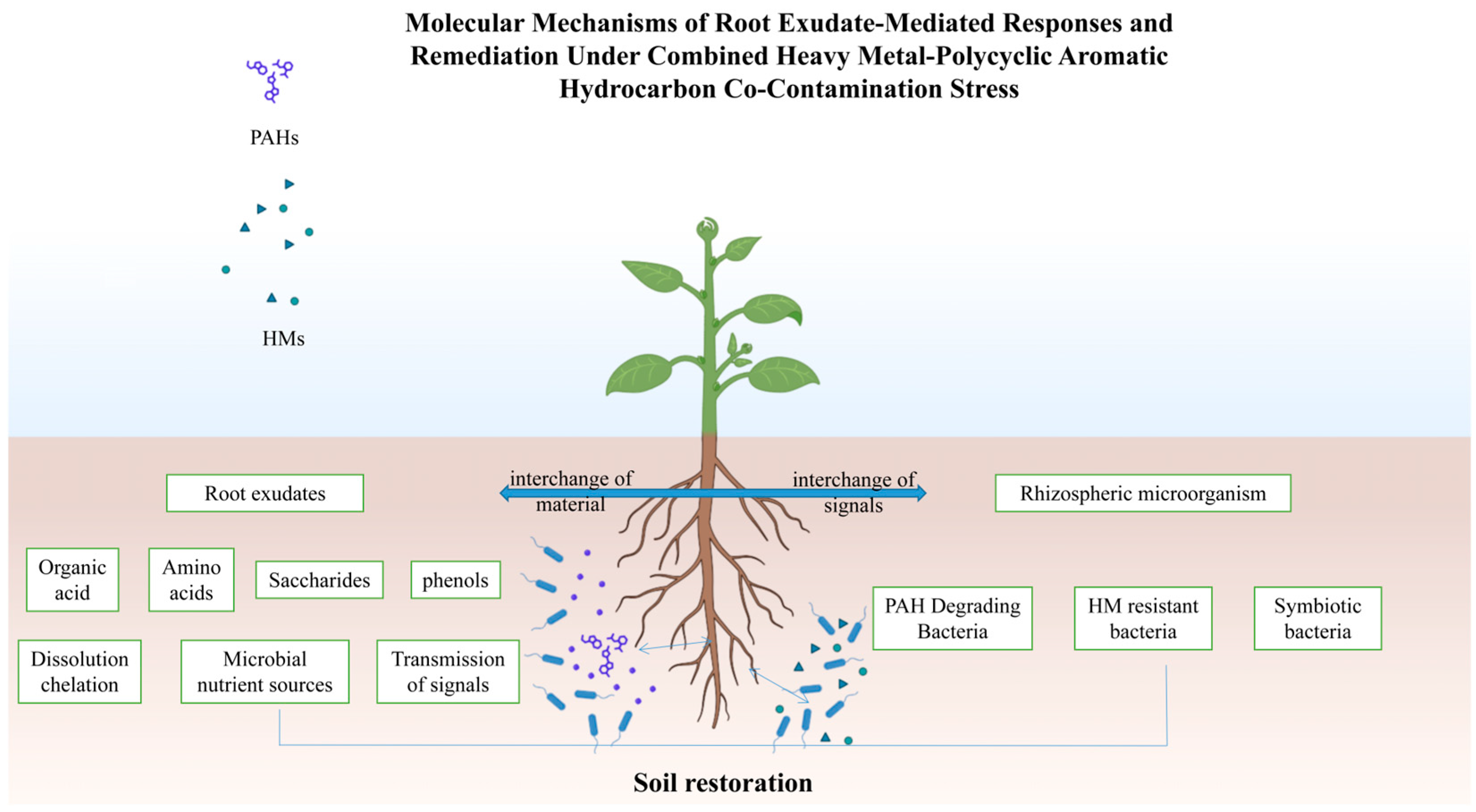

1. Introduction

2. Research Progress Domestically and Internationally

2.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Root Exudate Composition and Rhizosphere Microorganism Interactions

2.2. Effects of HMs-PAHs on Root Exudates Under Stress Conditions

2.2.1. Impact of Heavy Metal Stress on Root Exudates

2.2.2. Impact of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Stress on Root Exudates

2.2.3. Impact of HMs and PAHs on Root Exudates

2.3. Impacts of HMs-PAHs Stress on Rhizosphere Microorganisms

2.3.1. Impacts of Heavy Metal Stress on Rhizosphere Microorganisms

2.3.2. Impacts of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Stress on Rhizosphere Microorganisms

2.3.3. Effects of HMs-PAHs Combined Stress on Rhizosphere Microorganisms: An Integrated Analysis

2.4. Synergistic Interactions Between Root Exudates and Rhizosphere Microbes for Alleviating HMs-PAHs Stress

2.4.1. Repair Efficiency and Mechanism of Heavy Metals by Root Exudates and Rhizosphere Microorganisms

2.4.2. Repair Efficiency and Mechanism of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Stress by Root Exudates and Rhizosphere Microorganisms

2.4.3. Remediation Efficiency and Mechanism of Root Exudates for HMs-PAHs Contaminated Soils

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mai, X.; Tang, J.; Tang, J.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhuang, X.; Feng, G.; Tang, L. Research Progress on the Environmental Risk Assessment and Remediation Technologies of Heavy Metal Pollution in Agricultural Soil. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 149, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Wu, T.; Li, R.; Bian, G.; Jiao, H.; Bai, Z. Characterization of Microbial Community Structure in Long-Term Polycyclic AromaticHydrocarbon-Contaminated Soil. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 1885–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Tan, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, F.; Xu, H. Responsiveness Change of Biochemistry and Micro-Ecology in Alkaline Soil under PAHs Contamination with or without Heavy Metal Interaction. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, C. Research Progress on Co-Contamination and Remediation of Heavy Metals Andpolycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil and Groundwater. CIESC J. 2017, 68, 2219–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Liang, J.; Sun, Y. Overview on Several Typical Soil Pollution Remediation Technologies. Value Eng. 2013, 32, 313–314. [Google Scholar]

- Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Regulation and Function of Root Exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.S.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Kumar, V. Root Exudates Ameliorate Cadmium Tolerance in Plants: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1243–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Gangola, S.; Bhandari, G.; Bhandari, N.S.; Nainwal, D.; Rani, A.; Malik, S.; Slama, P. Rhizospheric Bacteria: The Key to Sustainable Heavy Metal Detoxification Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1229828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, S.A.; Griffiths, J.; Ton, J. Crying out for Help with Root Exudates: Adaptive Mechanisms by Which Stressed Plants Assemble Health-Promoting Soil Microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 49, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musilova, L.; Ridl, J.; Polivkova, M.; Macek, T.; Uhlik, O. Effects of Secondary Plant Metabolites on Microbial Populations: Changes in Community Structure and Metabolic Activity in Contaminated Environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micallef, S.A.; Shiaris, M.P.; Colón-Carmona, A. Influence of Arabidopsis thaliana Accessions on Rhizobacterial Communities and Natural Variation in Root Exudates. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, J.M.; Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Rhizosphere Microbiome Assemblage Is Affected by Plant Development. ISME J. 2014, 8, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, A.; Doucette, W.; Norton, J.; Bugbee, B. Changes in Crested Wheatgrass Root Exudation Caused by Flood, Drought, and Nutrient Stress. J. Environ. Qual. 2007, 36, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.M.; Fransson, P.M.A.; Finlay, R.D.; Van Hees, P.A.W. Quantitative Analysis of Soluble Exudates Produced by Ectomycorrhizal Roots as a Response to Ambient and Elevated CO2. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Friman, V.-P.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Mei, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Jousset, A. Pathogen Invasion Indirectly Changes the Composition of Soil Microbiome via Shifts in Root Exudation Profile. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2016, 52, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Vivanco, J.M.; Manter, D.K. Nitrogen Fertilizer Rate Affects Root Exudation, the Rhizosphere Microbiome and Nitrogen-Use-Efficiency of Maize. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 107, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-K.; Lin, X.-M.; Lin, W.-X. Advances and Perspective in Research on Plant-Soil-Microbe Interactions Mediated by Rootexudates. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2014, 38, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlawat, O.P.; Yadav, D.; Walia, N.; Kashyap, P.L.; Sharma, P.; Tiwari, R. Root Exudates and Their Significance in Abiotic Stress Amelioration in Plants: A Review. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 1736–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Wang, Y.; Yeh, K.-C. Role of Root Exudates in Metal Acquisition and Tolerance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghori, N.-H.; Ghori, T.; Hayat, M.Q.; Imadi, S.R.; Gul, A.; Altay, V.; Ozturk, M. Heavy Metal Stress and Responses in Plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1807–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, C.; Teng, C.; Linghu, S.; Shen, X.; Sun, C. The Mechanism of Rhizosphere Effect on Phytoremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil: A Review. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 52, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X. Review on the Mechanisms of the Response to Salinity-Alkalinity Stress in Plants. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 5565–5577. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The Physiology of Plant Responses to Drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Liang, C.; Lu, X.; Chen, Q. Mechanism of Root Exudates Regulating Plant Responses Tophosphorus Deficiency. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2019, 40, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Long, W.; Gu, T.; Wan, N.; Peng, B.; Kong, F.; Yuan, J. Effect of Low Iron Stress on Root Growth and Iron Uptake and Utili-Zation of Different Maize Cultivars at Seedling Stag. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2017, 25, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Jiang, Z.; Wei, S. Interaction of Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil-Crop Systems: The Effects and Mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, W.; Janda, T.; Molnár, Z. Unveiling the Significance of Rhizosphere: Implications for Plant Growth, Stress Response, and Sustainable Agriculture. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantigoso, H.A.; Newberger, D.; Vivanco, J.M. The Rhizosphere Microbiome: Plant–Microbial Interactions for Resource Acquisition. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2864–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-F.; Chaparro, J.M.; Reardon, K.F.; Zhang, R.; Shen, Q.; Vivanco, J.M. Rhizosphere Interactions: Root Exudates, Microbes, and Microbial Communities. Botany 2014, 92, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khade, O.; Sruthi, K. The Rhizosphere Microbiome: A Key Modulator of Plant Health and Their Role in Secondary Metabolites Production. In Biotechnology of Emerging Microbes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 327–349. ISBN 978-0-443-15397-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Tang, H.; Guo, J.; Pan, C.; Wang, R.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y. Root Exudates’ Roles and Analytical Techniques Progress. Soils 2023, 55, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Parasar, B.J.; Sharma, I.; Agarwala, N. Root Exudation Drives Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants by Recruiting Beneficial Microbes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 198, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Jia, H.; Ran, L.; Wu, F.; Liu, J.; Schlaeppi, K.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Wei, Z.; Zhou, X. Fusaric Acid Mediates the Assembly of Disease-Suppressive Rhizosphere Microbiota via Induced Shifts in Plant Root Exudates. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Shi, J.; Khashi, U.; Rahman, M.; Liu, H.; Wei, Z.; Wu, F.; Dini-Andreote, F. Volatile-Mediated Interspecific Plant Interaction Promotes Root Colonization by Beneficial Bacteria via Induced Shifts in Root Exudation. Microbiome 2024, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, V.A.; McGivern, B.B.; Borton, M.A.; Chaparro, J.M.; Schipanski, M.E.; Prenni, J.E.; Wrighton, K.C. Cover Crop Root Exudates Impact Soil Microbiome Functional Trajectories in Agricultural Soils. Microbiome 2024, 12, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Q.; Dong, S.; Hou, Q. Effects of Heavy Metal Cd, Pb Contamination on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Alfalfa. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2018, 46, 119–121+124. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xue, X.; Fei, Y. Effects of Heavy Metal Stress on Growth, Development and Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics of Panax Ginseng. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2016, 44, 253–256. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Gao, R.; Wang, A.; Yang, Y.; Ji, P.; Zhang, S.; Xing, X. Effects of Single and Combined Stresses of Mn and Cd on the Physiologicaland Biochemical Characteristics of Morus Alba. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2023, 43, 164–170+198. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Xu, Y.; Chi, Y.; Jin, Y. Effects of Pb Single and Pb-Cu Complex Stresses on Some Physiological Indexes of Typha Orientalis Presl. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2015, 24, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Küpper, H.; Küpper, F.; Spiller, M. In Situ Detection of Heavy Metal Substituted Chlorophylls in Water Plants. Photosynth. Res. 1998, 58, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigl, G.; Kumar, D.; Lehotai, N.; Pető, A.; Molnár, Á.; Rácz, É.; Ördög, A.; Erdei, L.; Kolbert, Z.; Laskay, G. Comparing the Effects of Excess Copper in the Leaves of Brassica juncea (L. Czern) and Brassica napus (L.) Seedlings: Growth Inhibition, Oxidative Stress and Photosynthetic Damage. Acta Biol. Hung. 2015, 66, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, A. Phenolic Compounds and Their Antioxidant Activity in Plants Growing under Heavy Metal Stress. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2006, 15, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, M.; Saeed, M.S.; Sattar, S.; Sajad, S.; Sajjad, M.; Adnan, M.; Iqbal, M.; Sharif, M.T. Specific Role of Proline Against Heavy Metals Toxicity in Plants. Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 2017, 5, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Cohen, M.; Trémulot, L.; Châtel-Innocenti, G.; Van Breusegem, F.; Mhamdi, A. Glutathione: A Key Modulator of Plant Defence and Metabolism through Multiple Mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 4549–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel-Rozas, M.M.; Madejón, E.; Madejón, P. Effect of Heavy Metals and Organic Matter on Root Exudates (Low Molecular Weight Organic Acids) of Herbaceous Species: An Assessment in Sand and Soil Conditions under Different Levels of Contamination. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 216, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapie, C.; Leglize, P.; Paris, C.; Buisson, T.; Sterckeman, T. Profiling of Main Metabolites in Root Exudates and Mucilage Collected from Maize Submitted to Cadmium Stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 17520–17534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affholder, M.C.; Moazzami, A.A.; Weih, M.; Kirchmann, H.; Herrmann, A.M. Cadmium Reduction in Spring Wheat: Root Exudate Composition Affects Cd Partitioning Between Roots and Shoots. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 3537–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, P.; Wu, E.; Ma, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhao, L.; et al. Cadmium Tolerance and Accumulation from the Perspective of Metal Ion Absorption and Root Exudates in Broomcorn Millet. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 250, 114506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingus, A.; Roslund, M.I.; Brauner, S.; Sinkkonen, A.; Weidenhamer, J.D. Arabidopsis Response to Copper Is Mediated by Density and Root Exudates: Evidence That Plant Density and Toxic Soils Can Shape Plant Communities. Am. J. Bot. 2024, 111, e16285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, W.; Yan, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, M.; Jiang, P.; Yu, G. Physiological Responses of Leersia Hexandra Swart to Cu and Ni Co-Contamination: Implications for Phytoremediation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Meng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Bi, Y.; Gao, X.; Lei, Y. Effects of Cadmium and Flooding on the Formation of Iron Plaques, the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Structure, and Root Exudates in Kandelia Obovata Seedlings. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.-P.; Dou, C.-M.; Hu, S.-P.; Chen, X.-C.; Shi, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-X. A review of progress in roles of organic acids on heavy metal resistance and detoxification inplants. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2010, 34, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, T.; Huang, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H. Effects of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids on the Speciation of Pb in Purple Soil and Soil Solution. Environ. Sci. 2016, 37, 1523–1530. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/medline/abstract/27548978 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Fu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Deng, Z.; Chen, M.; Yu, G.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, X. Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Reveal Key Genes and Metabolic Pathway Responses in Leersia Hexandra Swartz under Cr and Ni Co-Stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 473, 134590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Kobayashi, Y.; Wasaki, J.; Koyama, H. Organic Acid Excretion from Roots: A Plant Mechanism for Enhancing Phosphorus Acquisition, Enhancing Aluminum Tolerance, and Recruiting Beneficial Rhizobacteria. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2018, 64, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, W.; Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Mao, H.; Sheng, L.; Chen, Z. Community Metagenomics Reveals the Processes of Cadmium Resistance Regulated by Microbial Functions in Soils with Oryza Sativa Root Exudate Input. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çatav, Ş.S.; Elgin, E.S.; Küçükakyüz, K.; Dağ, Ç. Intrinsic and Induced Metabolic Signatures Underpin Aluminum Tolerance in Bread Wheat: A Comparative Metabolomics Approach. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2025, 31, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Mei, P. Activation and Remediation of Cu2+ and Cd2+ in Soil by Root Exudates and Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 45, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Maron, L.G.; Guimarães, C.T.; Kirst, M.; Albert, P.S.; Birchler, J.A.; Bradbury, P.J.; Buckler, E.S.; Coluccio, A.E.; Danilova, T.V.; Kudrna, D.; et al. Aluminum Tolerance in Maize Is Associated with Higher MATE1 Gene Copy Number. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5241–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, L.; Shen, Z.; Li, X. The Copper Tolerance Mechanisms of Elsholtzia Haichowensis, a Plant from Copper-Enriched Soils. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 51, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, K.; Huo, X.; Xu, X. Sources, Distribution, and Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Environ. Health 2011, 73, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Striganavičiūtė, G.; Hoffmann, T.; Schwab, W.; Sirgedaitė-Šėžienė, V. Silver Birch (Betula Pendula Roth) Response to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Implications for Growth Patterns and Secondary Metabolite Production. Trees 2025, 39, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zou, X.; Chen, G.; Shan, Q.; Zhang, J. Effect of Phenanthrene on Physiological Characteristics of Salix Jiangsuensis CL J-172 Seedlings. J. Jiangxi Univ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 33, 1–5+34. [Google Scholar]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Yu, J. Studies on Brassinosteroid-Induced Alleviation of Polyeyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Phytotoxicity and the Mechanism in Tomato. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Zhejiang, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Ling, W.T.; Gao, Y.Z. Plant Uptake of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Their Impacts on Root Exudates. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2010, 30, 593–599. [Google Scholar]

- Alkio, M.; Tabuchi, T.M.; Wang, X.; Colón-Carmona, A. Stress Responses to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Arabidopsis Include Growth Inhibition and Hypersensitive Response-like Symptoms. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2983–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xie, F.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Yan, C. Response of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Mangrove Root Exudates to Exposure of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 12484–12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Gong, Z.; Miao, R.; Su, D.; Li, X.; Jia, C.; Zhuang, J. The Influence of Root Exudates of Maize and Soybean on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Degradation and Soil Bacterial Community Structure. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 99, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, L.; Pan, P.; Li, R.; Lin, B. Response of Root Exudates of Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (L.) to Exposure of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 787002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Meng, F.; Zhang, W. Response of Amino Acids in Ryegrass Root Exudates to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbonstress. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2020, 39, 1937–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Muratova, A.; Pozdnyakova, N.; Golubev, S.; Wittenmayer, L.; Makarov, O.; Merbach, W.; Turkovskaya, O. Oxidoreductase Activity of Sorghum Root Exudates in a Phenanthrene-Contaminated Environment. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyanov, D.; Panchenko, L.; Pozdnyakova, N.; Muratova, A.; Medicago Sativa, L. Root Exudation of Phenolic Compounds and Effect of Flavonoids on Phenanthrene Degradation by Two Rhizobacteria. Front. Biosci.-Elite 2025, 17, 25779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, L.; Segura, A. Biochemical and Metabolic Plant Responses toward Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals Present in Atmospheric Pollution. Plants 2021, 10, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Song, B.; Feng, R. Factors Rest Restraining Uptake/Translocation of Heavy Metals (Metalloids)Related with Plant Roots and Its Mechanism. Res. Agric. Mod. 2021, 42, 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-Q.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Xuan, W.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.-J. Rice Roots Avoid Asymmetric Heavy Metal and Salinity Stress via an RBOH-ROS-Auxin Signaling Cascade. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1678–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Yan, Z. Effects of Root Exudates on Environmental Behavior of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Mangrove Sediments. Ph.D. Thesis, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Xia, B.; Feng, J.; Lin, X. Response of maize (Zea mays L.) root morphology to Cdand pyrene contamination in soil. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 16, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Effect of Combined Pollution of Cd and B[a]P on Photosynthesis and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Characteristics of Wheat. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 24, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barathan, M.; Ng, S.L.; Lokanathan, Y.; Ng, M.H.; Law, J.X. Plant Defense Mechanisms against Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Contamination: Insights into the Role of Extracellular Vesicles. Toxics 2024, 12, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, X. The Role of Root Exudates in Scirpustriqueter on Phytoremediation Ofpyrene-Lead Co-Contaminated Soil. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Cheng, J. Compound Exposure of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Cadmium Insoil and Its Biological Effects on Ryegrass. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Normal University, Nanjing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Wang, J.-X.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.-X.; Wu, X.-J. Interaction of Heavy Metals and Pyrene on Their Fates in Soil and Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Jin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, Q.; Xu, Y. Growth Response, Enrichment Effect, and Physiological Response of Different Garden Plants under Combined Stress of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals. Coatings 2022, 12, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tong, M.; Guo, S.; Li, F. Research Progress on Bioremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals Co-Contaminated Soil. Chin. J. Ecol. 2023, 42, 2874–2884. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Zhong, G.; Zhi, X. Progress in Effect of Rhizosphere Microbes on Phytoremediation of Polluted by Heavy Metal. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2009, 37, 14832–14834+14903. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Gu, S.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y.; Tao, Q.; Zhao, H.-P.; Liang, Y.; Banerjee, S.; Li, T. Core Microbiota in the Rhizosphere of Heavy Metal Accumulators and Its Contribution to Plant Performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 12975–12987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yin, H.; Liu, Z.; Luo, F.; Zhao, X.; Li, H.; Song, X. Root Exudate–Assisted Phytoremediation of Copper and Lead Contamination Using Rumex Acetosa L. and Rumex K-1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 117036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, B. Progress and Prospect of Plant Remediation Technology Joint with Other Technologies for Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil. Environ. Pollut. Control 2022, 44, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Q.; Chao, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, R. Research on Function of Rhizosphere Microbial Diversity in Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal Polluted Soils. J. South China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, H.; Tang, G.-X.; Huang, Y.-H.; Mo, C.-H.; Zhao, H.-M.; Xiang, L.; Li, Y.-W.; Li, H.; Cai, Q.-Y.; Li, Q.X. Response and Adaptation of Rhizosphere Microbiome to Organic Pollutants with Enriching Pollutant-Degraders and Genes for Bioremediation: A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margesin, R.; Labbé, D.; Schinner, F.; Greer, C.W.; Whyte, L.G. Characterization of Hydrocarbon-Degrading Microbial Populations in Contaminated and Pristine Alpine Soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3085–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ao, G.; Wang, Z.; Sun, S. Research Progress on Biological Enhancement of Soils Contaminated with Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Focusing on Bacterial Chemotaxis Mechanism and Application. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2025, 41, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, F.; Bao, Y. Variations of Microbiota and Metabolites in Rhizosphere Soil of Carmona Microphylla at the Co-Contaminated Site with Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhou, Y.; Li, N.; Hou, L.; Ma, Q.; Gao, B. Fire Phoenix Facilitates Phytoremediation of PAH-Cd Co-Contaminated Soil through Promotion of Beneficial Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaghi, Z.; Shirvani, M.; Nourbakhsh, F.; de la Peña, T.C.; Pueyo, J.É.J.; Talebi, M. Isolation and Characterization of Pb-Solubilizing Bacteria and Their Effects on Pb Uptake by Brassica Juncea: Implications for Microbe-Assisted Phytoremediation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, W.; Shao, M. Advance in Studies on Aluminum Toxicity and Plant Resistance. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2002, 6, 452–455. (In Chinese). Available online: https://syny.cbpt.cnki.net/portal/journal/portal/client/paper/ebc54aba91b041ad8e3fa39d6087d229 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Xu, J.-K.; Yang, L.-X.; Wang, Y.-L.; Wang, Z.-Q. Advances in the Study Uptake and Accumulation of Heavy Metal in Rice (Oryza sativa) and Its Mechanisms. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2005, 22, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q.; Chen, Y. Study on Chemical Behavior of Root Exudates with Heavy Metals. Plant Nutr. Fertil. Sci. 2003, 9, 425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Li, Z. Regulation of Rhizosphere Environment and Remediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2003, 12, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, H.; Xie, C.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, L.; An, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Li, D. Piriformospora Indica Colonization Enhances Remediation of Cadmium and Chromium Co-Contaminated Soils by King Grass through Plant Growth Promotion and Rhizosphere Microecological Regulation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 462, 132728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, X.; Lin, S.; Jiao, R.; Yang, X.; Shi, A.; Nie, X.; Lin, Q.; Qiu, R. Miscanthus Sp. Root Exudate Alters Rhizosphere Microb. Community Drive Soil Aggreg. Heavy Met. Immobilization. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundek, P.; Holík, L.; Hromádko, L.; Rohlík, T.; Vranová, V.; Rejšek, K.; Formánek, P. Action of Plant Root Exudates in Bioremediations: A Review. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2014, 59, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, X.; Jin, Y. Advances on Plant-Microbe Interaction Mediated by Rootmetabolites. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2022, 62, 3318–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Microbial Degradation Mechanism of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Rhizosphere Soil Under the Combined Action of Biochar and Root Exudates. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, S.C.; Yu, X.Z.; Wong, M.H. Dissipation Gradients of Phenanthrene and Pyrene in the Rice Rhizosphere. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 2596–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, C.; Zhang, D.; Cai, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, G. Diversity of the Active Phenanthrene Degraders in PAH-Polluted Soil Is Shaped by Ryegrass Rhizosphere and Root Exudates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 128, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovskaya, E.; Pozdnyakova, N.; Golubev, S.; Muratova, A.; Grinev, V.; Bondarenkova, A.; Turkovskaya, O. Peroxidases from Root Exudates of Medicago Sativa and Sorghum Bicolor: Catalytic Properties and Involvement in PAH Degradation. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Sun, L. Regulation of Rhamnolipids on Phytoremediation-Microorganism Combined Remediation DDTs-PAHs Contaminated Soil Research. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang University, Shenyang, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Effect of Artificial Root Exudates on the Sorption and Desorption of PAHs in Meadow Brown Soils. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1890, 040012. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, K.; Luo, Y. Bioremediation of Copper and Benzo[a]Pyrene-Contaminated Soil by Alfalfa. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2005, 24, 766–770. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, W.; Luo, Y.; Wu, L.; Song, J.; Teng, Y.; Li, Z. Growth and Absorption of Ryegrass on Acid Soil Contaminated by Lead and Benzo [a] Pyrene. ACTA Pedol. Sin. 2008, 45, 485–490. [Google Scholar]

| Stress Type | Representative Secretion Changes | Core Physiological and Ecological Functions |

|---|---|---|

| HMs (e.g., Cd, Pb, Cu) | increased secretion of low-molecular-weight organic acids (including citrate and malate), and enhanced accumulation/secretion of secondary metabolites (like phenolics and flavonoids). | Key Mechanisms of Detoxification and Immobilization: Reduced metal bioavailability via chelation and precipitation. Activated antioxidant defenses encompassing both enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems to alleviate oxidative stress. |

| PAHs (e.g., Phe, Pyr, BaP) | Characterized by an early enhancement of low-molecular-weight organic acids (e.g., oxalate, citrate) and a concomitant increase in sugars and amino acids that provided essential carbon and nitrogen sources for soil microbes. | Key Mechanisms of Solubilization and Co-metabolism: Increased PAH bioavailability by promoting their desorption from soil particles. Provided substrates and energy to microbial communities to facilitate co-metabolic degradation. |

| HMs-PAHs | The secretion of specific organic acids (e.g., citrate, succinate) displayed both synergistic and antagonistic dynamics. This was accompanied by a pronounced upregulation of secondary metabolic pathways and the synthesis of osmolytes such as proline. | Synergistic Resistance and Trade-offs: While the plant mounted a coordinated defense against both contaminants, the interplay between the two stressors could disrupt the root exudate profile, representing a significant physiological trade-off. To maintain cellular integrity under these conditions, the plant reinforced its cell walls (via lignification) and enhanced its oxidative stress defense systems. |

| Stress Type | Rhizosphere Microorganisms | The Role of Root Exudates in Mediating Interactions and Remediation Mechanisms | Literature Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMs(Pb) | Brevibacterium frigoritolerans YSP40, Bacillus paralleleniformis YSP151 | The bacterial strain improved lead (Pb) phytoextraction via two concurrent mechanisms: it acidified the rhizosphere by secreting organic acids, which solubilized refractory Pb minerals (e.g., PbO and PbCO3) and increased Pb bioavailability; while simultaneously promoting plant biomass through the secretion of the phytohormone IAA. Ultimately, this dual action elevated Pb accumulation in the mustard plants by up to 4.6-fold. | [81] |

| PAHs | Sphingomonas, Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Mycobacterium, Rhodococcus | Root exudates (e.g., organic acids, sugars, amino acids) provide carbon and nitrogen sources that enrich PAH-degrading bacteria. These microbes possess PAH-RHD genes (encoding ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase), which drives the initial hydroxylation and degradation of PAHs. The exudates also enhance PAH bioavailability, collectively promoting contaminant removal. | [90] |

| HMs-PAHs | Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria (e.g., Sphingomonas, Pseudomonas) | In response to the combined stress of HMs and PAHs, ryegrass altered its root exudate profile (e.g., organic acids, amino acids, and phenolics). This shift selectively enriched specific microbial taxa equipped with dual functions for tackling both contaminants. HMs immobilization was primarily mediated by Actinobacteria, which secreted organic acids like citrate and oxalate to chelate HMs, effectively reducing its bioavailability. PAH degradation was driven by genera such as Sphingomonas and Pseudomonas. These bacteria utilized root-derived carbon to express the PAH-RHDα gene, catalyzing the initial hydroxylation and ring-cleavage of PAHs. | [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, L.; Mo, J.; Wang, Z.; Lin, S.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Guo, W.; Chen, J.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Root Exudate-Mediated Remediation in Soils Co-Contaminated with Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Toxics 2025, 13, 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121044

Sun L, Mo J, Wang Z, Lin S, Wang D, Li Z, Wang Y, Wu J, Guo W, Chen J, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Root Exudate-Mediated Remediation in Soils Co-Contaminated with Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121044

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Lingyun, Jinling Mo, Zhenjiang Wang, Sen Lin, Dan Wang, Zhiyi Li, Yuan Wang, Jianan Wu, Wuyan Guo, Jiehua Chen, and et al. 2025. "Molecular Mechanisms of Root Exudate-Mediated Remediation in Soils Co-Contaminated with Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121044

APA StyleSun, L., Mo, J., Wang, Z., Lin, S., Wang, D., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Wu, J., Guo, W., Chen, J., Wu, Z., & Chen, L. (2025). Molecular Mechanisms of Root Exudate-Mediated Remediation in Soils Co-Contaminated with Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Toxics, 13(12), 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121044