Prenatal Exposure to Toxic Metals and Early Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Following Intrauterine Blood Transfusion: A Prospective Cohort Study

Highlights

- Mercury, arsenic, cadmium, and lead were detected in most maternal, cord, and intrauterine transfusion (IUBT) blood samples.

- Metal levels in IUBT bags were higher than in maternal or cord blood, suggesting an additional exposure pathway.

- Modest reductions in ASQ-3 scores (personal–social, problem-solving, and gross motor) were observed with higher metal levels, though effect sizes were small.

- PCA suggested exploratory patterns of combined metal exposure, but with limited stability due to low sampling adequacy.

- Even low-level metal contamination in transfusion products may contribute to prenatal exposure and warrants careful monitoring of medical supplies used during pregnancy.

- Observed associations were modest and exploratory, highlighting the need for larger studies with longer neurodevelopmental follow-up.

- Findings support strengthened quality-control procedures for IUBT and emphasize continued assessment of environmental and medical-related exposures in vulnerable fetal populations.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Blood Sample Collection

2.3. Blood/RBC Sample Preparation and Analysis

2.4. Two-Month Follow-Up

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics and Exposure Profile of the Study Population

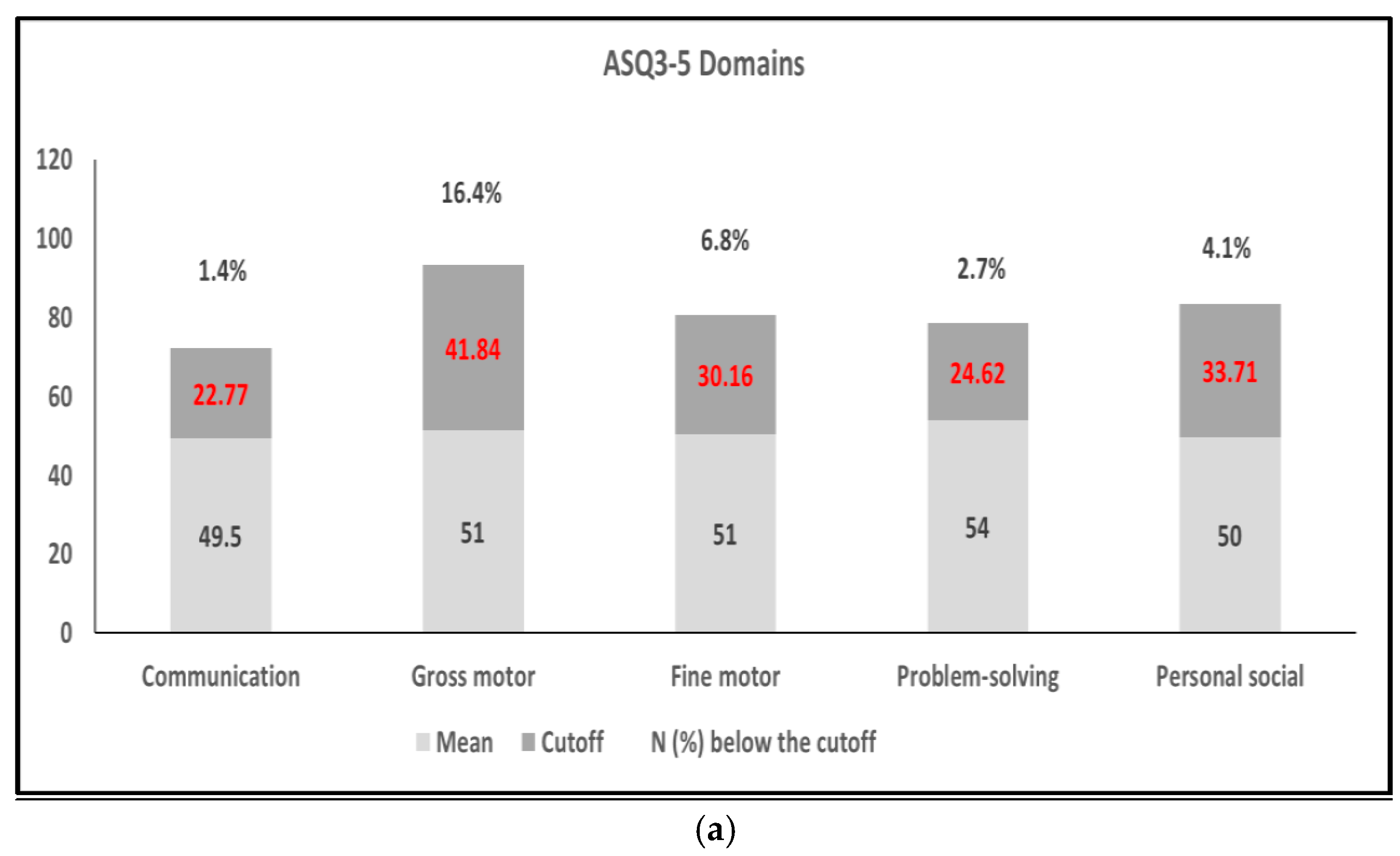

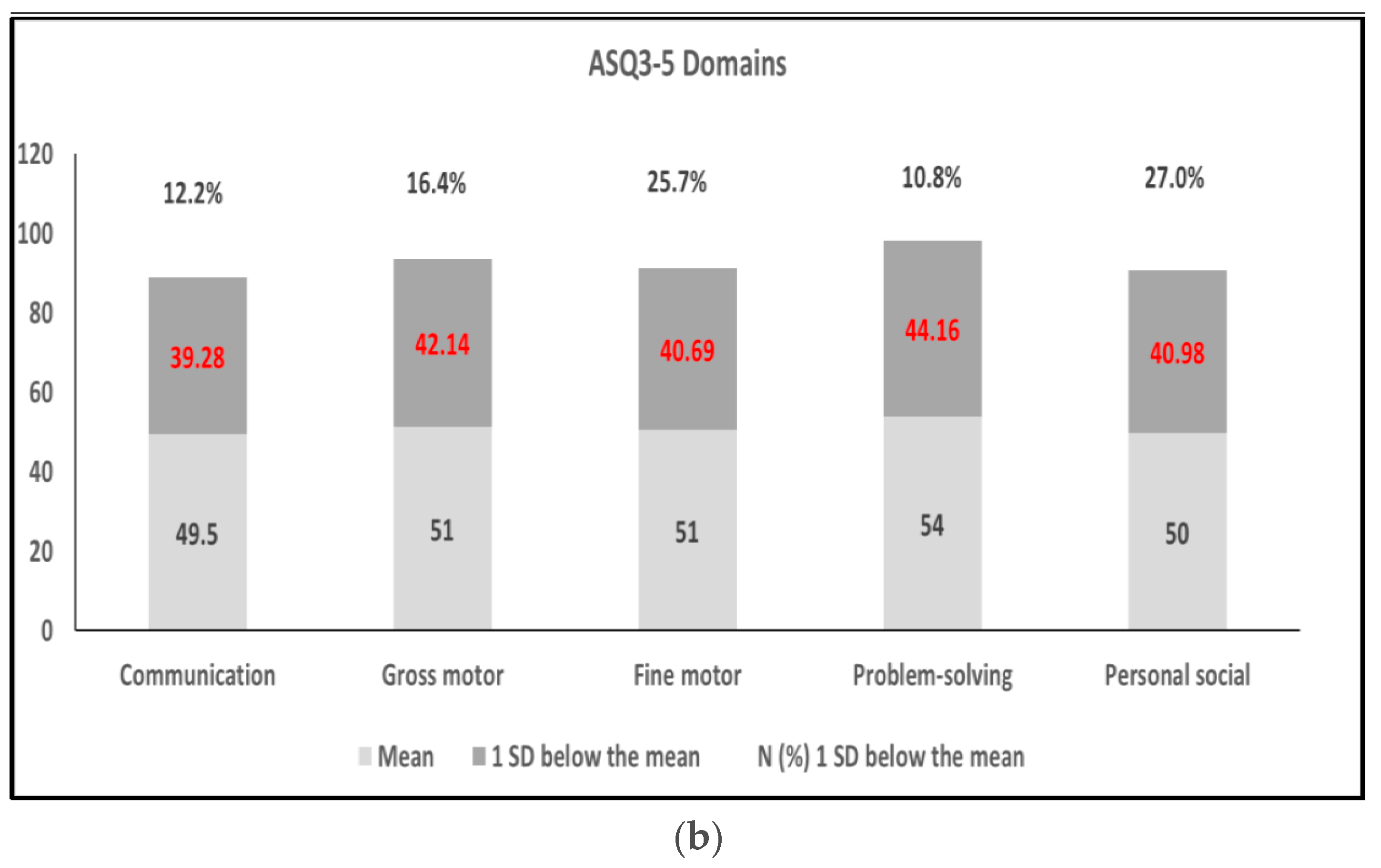

3.2. ASQ-3 Assessment and Relationship with Risk Factors

3.3. Risk Factors Associated with the Five Domains of the ASQ-3 and/or Metal Exposure

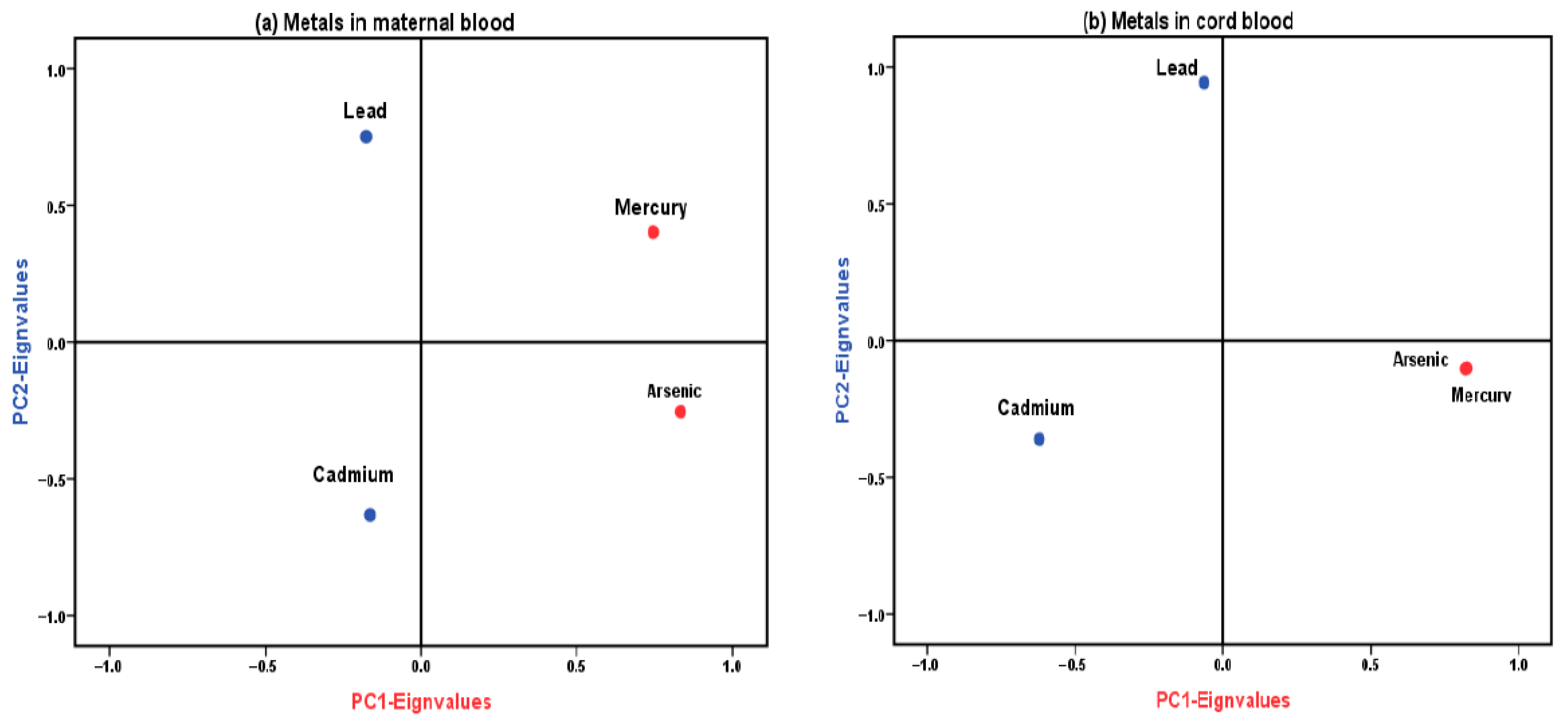

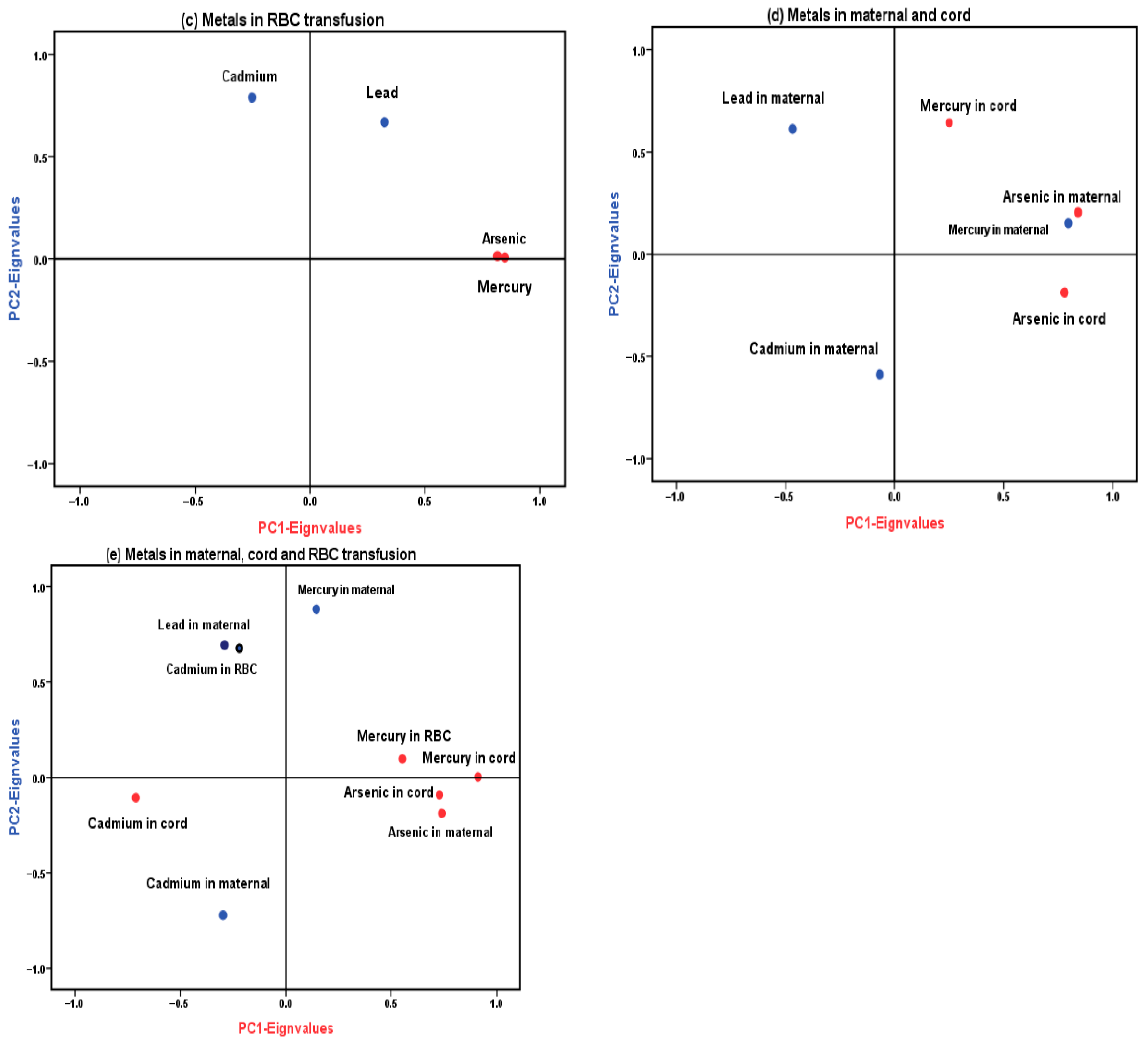

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.5. Regression Models

3.5.1. Initial Analysis Without the IUBT

3.5.2. RBC Transfusion Analysis

3.5.3. Analysis Including the IUBT

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. The Extent of Exposure to Heavy Metals in All Pregnant Women

4.3. Exposure Levels in the Context of the IUBT

4.4. Exposure and Neurodevelopment

4.5. Study Limitations and Strengths

4.6. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Needham, L.L.; Barr, D.B.; Caudill, S.P.; Pirkle, J.L.; Turner, W.E.; Osterloh, J.; Jones, R.L.; Sampson, E.J. Concentrations of Environmental Chemicals Associated with Neurodevelopmental Effects in U.S. Population. Neurotoxicology 2005, 26, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Lambertini, L.; Birnbaum, L.S. A research strategy to discover the environmental causes of autism and neurodevelopmental disabilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, a258–a260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurewicz, J.; Polanska, K.; Hanke, W. Chemical exposure early in life and the neurodevelopment of children—An overview of current epidemiological evidence. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2013, 20, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Landrigan, P.J. Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Toxicological Effects of Methylmercury; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazmy, M.B.; Al Sweilan, B.; Al-Moussa, N.B. Handicap among children in Saudi Arabia: Prevalence, distribution, type, determinants and related factors. East. Mediterr. Health 2004, 10, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Salloum, A.A.; El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Omar, A.A.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Qurashi, M.M. The prevalence of neurological disorders in Saudi children: A community-based study. J. Child Neurol. 2011, 26, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jadid, M.S. Disability in Saudi Arabia. Saudi. Med. J. 2013, 34, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2014, 7, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.N.; Tangpong, J.; Rahman, M.M. Toxicodynamics of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury and Arsenic- induced kidney toxicity and treatment strategy: A mini review. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Fatima, F.; Waheed, I.; Akash, M.S.H. Prevalence of exposure of heavy metals and their impact on health consequences. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, V.M.; Aschner, M.; Marreilha Dos Santos, A.P. Neurotoxicity of Metal Mixtures. Adv. Neurobiol. 2017, 18, 227–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, F.M.; Caldas, E.D. Arsenic, lead, mercury and cadmium: Toxicity, levels in breast milk and the risks for breastfed infants. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC, International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Beryllium, Cadmium, Mercury, and Exposures in the Glass Manufacturing Industry; IARC: Lyon, France, 1993; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- IARC, International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Arsenic, Metals, Fibres and Dusts; IARC: Lyon, France, 2012; p. 100C. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Huo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, X.; Du, L.; Xu, X.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, J. Short placental telomere was associated with cadmium pollution in an electronic waste recycling town in China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, J.; Sirot, V.; Hulin, M.; Le Calvez, E.; Zinck, J.; Noel, L.; Vasseur, P.; Nesslany, F.; Gorecki, S.; Guerin, T.; et al. Dietary exposure to cadmium and health risk assessment in children—Results of the French infant total diet study. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 115, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.B.; Hsueh, Y.M.; Kuo, G.L.; Hsu, C.H.; Chang, J.H.; Chien, L.C. Preliminary study of urinary arsenic concentration and arsenic methylation capacity effects on neurodevelopment in very low birth weight preterm children under 24 months of corrected age. Medicine 2018, 97, e12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, X.; Yu, X. Prenatal exposure to arsenic and neurobehavioral development of newborns in China. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Inorganic Lead: Environmental Health Criteria 165; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, M.; Wright, R.O.; Amarasiriwardena, C.J.; Jayawardene, I.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Oken, E. Very low maternal lead level in pregnancy and birth outcomes in an eastern Massachusetts population. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Golding, J.; Emond, A.M. Adverse effects of maternal lead levels on birth outcomes in the ALSPAC study: A prospective birth cohort study. BJOG 2015, 122, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, Y.; Markowitz, M.E.; Rosen, J.F. Low-level lead-induced neurotoxicity in children: An update on central nervous system effects. Brain Res. Rev. 1998, 27, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counter, S.; Buchanan, L.; Ortega, F. Neurocognitive impairment in lead-exposed children of Andean lead-glazing workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 47, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, T.W.; Magos, L. The toxicology of mercury and its chemical compounds. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2006, 36, 609–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose-O’Reilly, S.; McCarty, K.M.; Steckling, N.; Lettmeier, B. Mercury Exposure and Children’s Health. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2010, 40, 186–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, K.M.; Walker, E.M.; Wu, M.; Gillette, C.; Blough, E.R. Environmental Mercury and Its Toxic Effects. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2014, 47, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorea, J.G. Low-dose mercury exposure in early life: Relevance of thimerosal to fetuses, newborns and infants. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 4060–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, World Health Organization and IPCS, International Programme on Chemical Safety. Elemental Mercury and Inorganic Mercury Compounds: Human Health Aspects, Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 50; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Mercury; ATSDR: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Prefumo, F.; Fichera, A.; Fratelli, N.; Sartori, E. Fetal anemia: Diagnosis and management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 58, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Riyami, A.Z.; Al-Salmani, M.; Al-Hashami, S.N.; Al-Mahrooqi, S.; Al-Marhoobi, A.; Al-Hinai, S.; Al-Hosni, S.; Panchatcharam, S.M.; Al-Arimi, Z.A. Intrauterine Fetal Blood Transfusion: Descriptive study of the first four years’ experience in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2018, 18, e34–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduin, E.P.; Lindenburg, I.T.; Smits-Wintjens, V.E.; van Klink, J.M.; Schonewille, H.; van Kamp, I.L.; Oepkes, D.; Walther, F.J.; Kanhai, H.H.; Doxiadis, I.I.; et al. Long-Term follow up after intra-Uterine transfusions; the LOTUS study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenburg, I.T.; van Klink, J.M.; Smits-Wintjens, V.E.; van Kamp, I.L.; Oepkes, D.; Lopriore, E. Long-term neurodevelopmental and cardiovascular outcome after intrauterine transfusions for fetal anaemia: A review. Prenat Diagn. 2013, 33, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Klink, J.M.; Koopman, H.M.; Oepkes, D.; Walther, F.J.; Lopriore, E. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcome after intrauterine transfusion for fetal anemia. Early Hum. Dev. 2011, 87, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbey, E.A.; Thibodeaux, S.R. Ensuring safety of the blood supply in the United States: Donor screening, testing, emerging pathogens, and pathogen inactivation. Semin. Hematol. 2019, 56, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averina, M.; Hervig, T.; Huber, S.; Kjaer, M.; Kristoffersen, E.K.; Bolann, B. Environmental pollutants in blood donors: The multicentre Norwegian donor study. Transfus. Med. 2020, 30, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, S.M.; Omran, A.; Abdalla, M.O.; Gaulier, J.M.; El-Metwally, D. Lead: A hidden “untested” risk in neonatal blood transfusion. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 85, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.M.R.; Anderson Berry, A.L.; White, S.F.; Moran, D.; Lyden, E.; Bearer, C.F. Donor blood remains a source of heavy metal exposure. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 85, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrie, E.; Keiser, A.; Dawling, S.; Travis, J.; Strathmann, F.G.; Booth, G.S. Primary prevention of pediatric lead exposure requires new approaches to transfusion screening. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schulz, C.; Wilhelm, M.; Heudorf, U.; Kolossa-Gehring, M. Update of the reference and HBM values derived by the German Human Biomonitoring Commission. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 215, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, C.; Angerer, J.; Ewers, U.; Kolossa-Gehring, M. The German Human Biomonitoring Commission. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2007, 210, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.; Heinzow, B.; Angerer, J.; Schulz, C. Reassessment of critical lead effects by the German Human Biomonitoring Commission results in suspension of the human biomonitoring values (HBM I and HBM II) for lead in blood of children and adults. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2010, 213, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.; Trujillo, K.A. Neurotoxicity of low-level lead exposure: History, mechanisms of action, and behavioral effects in humans and preclinical models. Neurotoxicology 2019, 73, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckart, P.Z.; Jones, R.L.; Courtney, J.G.; LeBlanc, T.T.; Jackson, W.; Karwowski, M.P.; Cheng, P.Y.; Allwood, P.; Svendsen, E.R.; Breysse, P.N. Update of the Blood Lead Reference Value—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1509–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, I.; Alnuwaysir, H.; Al-Rouqi, R.; Aldhalaan, H.; Tulbah, M. Fetal exposure to toxic metals (mercury, cadmium, lead, and arsenic) via intrauterine blood transfusions. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 97, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, K.J. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1990, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, G.; Thunell, E. Reversing Bonferroni. Psychon. Bull Rev. 2021, 28, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US EPA. Mercury: Human Exposure; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey, K.R.; Clickner, R.P.; Jeffries, R.A. Adult women’s blood mercury concentrations vary regionally in the United States: Association with patterns of fish consumption (NHANES 1999–2004). Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahaffey, K.R. Mercury exposure: Medical and public health issues. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2005, 116, 127–153. Discussion 153–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Saleh, I.; Shinwari, N.; Mashhour, A.; Mohamed Gel, D.; Rabah, A. Heavy metals (lead, cadmium and mercury) in maternal, cord blood and placenta of healthy women. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedrychowski, W.; Perera, F.; Jankowski, J.; Rauh, V.; Flak, E.; Caldwell, K.L.; Jones, R.L.; Pac, A.; Lisowska-Miszczyk, I. Fish consumption in pregnancy, cord blood mercury level and cognitive and psychomotor development of infants followed over the first three years of life: Krakow epidemiologic study. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, S.A.; Jones, R.L.; Caldwell, K.L.; Rauh, V.; Sheets, S.E.; Tang, D.; Viswanathan, S.; Becker, M.; Stein, J.L.; Wang, R.Y.; et al. Relation between cord blood mercury levels and early child development in a World Trade Center cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.L.; Li, G.G.; Shaha, S. Antepartum seafood consumption and mercury levels in newborn cord blood. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1683–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.H.; Smith, A.E. An assessment of the cord blood:maternal blood methylmercury ratio: Implications for risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1465–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Exposure Report Data Tables; CDC: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Update of the Blood Lead Reference Value—United States; CDC: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, B.M.; Dolan, L.C.; Hoffman-Pennesi, D.; Gavelek, A.; Jones, O.E.; Kanwal, R.; Wolpert, B.; Gensheimer, K.; Dennis, S.; Fitzpatrick, S.U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s interim reference levels for dietary lead exposure in children and women of childbearing age. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 110, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA 3136-06R; Cadmium. OSHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- García-Esquinas, E.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Fernández-Navarro, P.; Fernández, M.A.; de Paz, C.; Pérez-Meixeira, A.M.; Gil, E.; Iriso, A.; Sanz, J.C.; Astray, J.; et al. Lead, mercury and cadmium in umbilical cord blood and its association with parental epidemiological variables and birth factors. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, R.; Cohen, C.; Pulcinelli, R.; Caletti, G.; Balsan, A.; Nascimento, S.; Rocha, R.; Calderon, E.; Saint’Pierre, T.; Garcia, S.; et al. Toxic elements in packed red blood cells from smoker donors: A risk for paediatric transfusion? Vox Sang 2019, 114, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Song, W.; Hong, D.; Huang, L.; Li, Y. A review on Cadmium Exposure in the Population and Intervention Strategies Against Cadmium Toxicity. Bull Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 106, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Piao, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Xu, L.; Kitamura, F.; Yokoyama, K. Prenatal exposure to arsenic and its effects on fetal development in the general population of Dalian. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2012, 149, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, A.M.; Amarasiriwardena, C.; Cantoral-Preciado, A.; Claus Henn, B.; Leon Hsu, H.H.; Sanders, A.P.; Svensson, K.; Tamayo-Ortiz, M.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Wright, R.O.; et al. Maternal blood arsenic levels and associations with birth weight-for-gestational age. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanabhavan, G.; Werry, K.; Walker, M.; Haines, D.; Malowany, M.; Khoury, C. Human biomonitoring reference values for metals and trace elements in blood and urine derived from the Canadian Health Measures Survey 2007–2013. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai-Shimada, M.; Kameo, S.; Nakai, K.; Yaginuma-Sakurai, K.; Tatsuta, N.; Kurokawa, N.; Nakayama, S.F.; Satoh, H. Exposure profile of mercury, lead, cadmium, arsenic, antimony, copper, selenium and zinc in maternal blood, cord blood and placenta: The Tohoku Study of Child Development in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, N.D.; Araújo, M.S.; Luiz, R.R.; de Magalhaes Câmara, V.; do Couto Jacob, S.; Dos Santos, L.M.G.; Vicentini, S.A.; Asmus, C. Metal mixtures in pregnant women and umbilical cord blood at urban populations-Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 40210–40218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhuang, T.; Shi, J.; Liang, Y.; Song, M. Heavy metals in maternal and cord blood in Beijing and their efficiency of placental transfer. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 80, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, M.H.; Samms-Vaughan, M.; Dickerson, A.S.; Hessabi, M.; Bressler, J.; Desai, C.C.; Shakespeare-Pellington, S.; Reece, J.A.; Morgan, R.; Loveland, K.A.; et al. Concentration of lead, mercury, cadmium, aluminum, arsenic and manganese in umbilical cord blood of Jamaican newborns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2015, 12, 4481–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röllin, H.B.; Channa, K.; Olutola, B.G.; Odland, J. Evaluation of in utero exposure to arsenic in South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley-Martin, J.; Fisher, M.; Belanger, P.; Cirtiu, C.M.; Arbuckle, T.E. Biomonitoring of inorganic arsenic species in pregnancy. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulson, J.A.; Brown, M.J. The CDC blood lead reference value for children: Time for a change. Environ. Health 2019, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Assis Araujo, M.S.; Froes-Asmus, C.I.R.; de Figueiredo, N.D.; Camara, V.M.; Luiz, R.R.; Prata-Barbosa, A.; Martins, M.M.; Jacob, S.D.C.; Santos, L.; Vicentini Neto, S.A.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Metals and Neurodevelopment in Infants at Six Months: Rio Birth Cohort Study of Environmental Exposure and Childhood Development (PIPA Project). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbone, F.; Rosolen, V.; Mariuz, M.; Parpinel, M.; Casetta, A.; Sammartano, F.; Ronfani, L.; Vecchi Brumatti, L.; Bin, M.; Castriotta, L.; et al. Prenatal mercury exposure and child neurodevelopment outcomes at 18 months: Results from the Mediterranean PHIME cohort. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, P.; Hernández-Bonilla, D.; Moreno-Macías, H.; Montes-López, S.; Schnaas, L.; Texcalac-Sangrador, J.L.; Ríos, C.; Riojas-Rodríguez, H. Prenatal Co-Exposure to Manganese, Mercury, and Lead, and Neurodevelopment in Children during the First Year of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Itoh, S.; Miyashita, C.; Ait Bamai, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Masuda, H.; Itoh, M.; Yamazaki, K.; Tamura, N.; Hanley, S.J.B.; et al. Impact of prenatal exposure to mercury and selenium on neurodevelopmental delay in children in the Japan environment and Children’s study using the ASQ-3 questionnaire: A prospective birth cohort. Environ. Int. 2022, 168, 107448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barranco, M.; Lacasaña, M.; Aguilar-Garduño, C.; Alguacil, J.; Gil, F.; González-Alzaga, B.; Rojas-García, A. Association of arsenic, cadmium and manganese exposure with neurodevelopment and behavioural disorders in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 454–455, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R.P.; Umezaki, M.; Fujiwara, T.; Watanabe, C. Association of cord blood levels of lead, arsenic, and zinc and home environment with children neurodevelopment at 36 months living in Chitwan Valley, Nepal. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R.P.; Fujiwara, T.; Umezaki, M.; Watanabe, C. Association of cord blood levels of lead, arsenic, and zinc with neurodevelopmental indicators in newborns: A birth cohort study in Chitwan Valley, Nepal. Environ. Res. 2013, 121, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R.P.; Fujiwara, T.; Umezaki, M.; Watanabe, C. Home environment and cord blood levels of lead, arsenic, and zinc on neurodevelopment of 24 months children living in Chitwan Valley, Nepal. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2015, 29, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Wu, X.; Huang, K.; Yan, S.; Li, Z.; Xia, X.; Pan, W.; Sheng, J.; Tao, R.; Tao, Y.; et al. Domain- and sex-specific effects of prenatal exposure to low levels of arsenic on children’s development at 6 months of age: Findings from the Ma’anshan birth cohort study in China. Environ. Int. 2020, 135, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Iwai-Shimada, M.; Nakayama, S.F.; Isobe, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tatsuta, N.; Taniguchi, Y.; Sekiyama, M.; Michikawa, T.; Yamazaki, S.; et al. Association of prenatal exposure to cadmium with neurodevelopment in children at 2 years of age: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, R.; Tian, Y. Effects of prenatal exposure to cadmium on neurodevelopment of infants in Shandong, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 211, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, A.; Radcliffe, J.; Dietrich, K.N.; Jones, R.L.; Caldwell, K.; Rogan, W.J. Postnatal cadmium exposure, neurodevelopment, and blood pressure in children at 2, 5, and 7 years of age. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ha, E.-H.; Park, H.; Ha, M.; Kim, Y.; Hong, Y.-C.; Kim, E.-J.; Kim, B.-N. Prenatal lead and cadmium co-exposure and infant neurodevelopment at 6 months of age: The Mothers and Children’s Environmental Health (MOCEH) study. Neurotoxicology 2013, 35, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, T.; Amano, H.; Otani, S.; Kamijima, M.; Yamazaki, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kurozawa, Y. Association between prenatal cadmium exposure and child development: The Japan Environment and Children’s study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 243, 113989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, K.; Brown, T.; Spurgeon, A.; Levy, L. Recent developments in low-level lead exposure and intellectual impairment in children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanphear, B.P.; Dietrich, K.; Auinger, P.; Cox, C. Cognitive deficits associated with blood lead concentrations <10 microg/dL in US children and adolescents. Public Health Rep. 2000, 115, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, I.; Shinwari, N.; Nester, M.; Mashhour, A.; Moncari, L.; El Din Mohamed, G.; Rabah, A. Longitudinal study of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia: A preliminary results of cord blood lead levels. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2008, 54, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, I.; Al-Rouqi, R.; Alnuwaysir, H.; Aldhalaan, H.; Alismail, E.; Binmanee, A.; Hawari, A.; Alhazzani, F.; Bin Jabr, M. Exposure of preterm neonates to toxic metals during their stay in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and its impact on neurodevelopment at 2 months of age. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 78, 127173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falck, A.J.; Sundararajan, S.; Al-Mudares, F.; Contag, S.A.; Bearer, C.F. Fetal exposure to mercury and lead from intrauterine blood transfusions. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 86, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, M.; Iyigun, I.; Yalcin, S.S.; Cagan, M.; Cakir, D.A.; Celik, H.T.; Deren, O.; Erkekoglu, P. Perinatal Exposure to Heavy Metals and Trace Elements of Preterm Neonates in the NICU: A Toxicological Study Using Multiple Biomatrices. Toxics 2025, 13, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, S.M.; Elfiky, S.; Mohamed, Y.G.; Soliman, R.A.M.; Shalaby, N.; Beauval, N.; Gaulier, J.M.; Allorge, D.; Omran, A. Lead, Mercury, and Cadmium Concentrations in Blood Products Transfused to Neonates: Elimination Not Just Mitigation. Toxics 2023, 11, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne-Sturges, D.C.; Taiwo, T.K.; Ellickson, K.; Mullen, H.; Tchangalova, N.; Anderko, L.; Chen, A.; Swanson, M. Disparities in Toxic Chemical Exposures and Associated Neurodevelopmental Outcomes: A Scoping Review and Systematic Evidence Map of the Epidemiological Literature. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 96001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dack, K.; Fell, M.; Taylor, C.M.; Havdahl, A.; Lewis, S.J. Prenatal Mercury Exposure and Neurodevelopment up to the Age of 5 Years: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Maria, M.P.; Hill, B.D.; Kline, J. Lead (Pb) neurotoxicology and cognition. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2019, 8, 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenis, L.J.; Verhoeven, M.; Hessen, D.J.; van Baar, A.L. Parental and professional assessment of early child development: The ASQ-3 and the Bayley-III-NL. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, S.; Nash, A.; Braun, A.; Bastug, G.; Rougeaux, E.; Bedford, H. Evaluating the Use of a Population Measure of Child Development in the Healthy Child Programme Two Year Review; University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2014; pp. 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L.E.; Perkins, K.A.; Dai, Y.G.; Fein, D.A. Comparison of Parent Report and Direct Assessment of Child Skills in Toddlers. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2017, 41–42, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csima, M.; Podráczky, J.; Keresztes, V.; Soós, E.; Fináncz, J. The Role of Parental Health Literacy in Establishing Health-Promoting Habits in Early Childhood. Children 2024, 11, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, J.; Bricker, D. Ages & Stages Questionnaires (ASQ3): A Parent-Completed Child-Monitoring System; Paul Brookes Publishing Company: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maitre, L.; Julvez, J.; López-Vicente, M.; Warembourg, C.; Tamayo-Uria, I.; Philippat, C.; Gützkow, K.B.; Guxens, M.; Andrusaityte, S.; Basagaña, X.; et al. Early-life environmental exposure determinants of child behavior in Europe: A longitudinal, population-based study. Environ. Int. 2021, 153, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Sample Preparation |

|

| Instrumentation |

|

| Calibration |

|

| Analytical Accuracy |

|

| Between-Run Precision | Pooled blood spiked at 0.75, 1.5, 3 µg/L:

|

| Within-Run Precision | Ten replicates at 0.3, 0.75, 1.5 µg/L:

|

| Standard Reference Materials | * ClinChek® (three levels):

|

| ** Limit of Detection (LOD) |

|

| *** Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) |

|

| a | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Variables: Demographic/Clinical/ASQ-3-Domains | No IUBT Recipients | IUBT Recipients | p-Value | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | ||

| Mother’s age (years) | 60 | 32.8 | 31.7 | 25.8 | 45.7 | 30 | 35.8 | 36.1 | 29.6 | 46.0 | 0.001 |

| Weight (Kg) | 60 | 79.6 | 78.5 | 47.9 | 139.0 | 30 | 80.4 | 78.5 | 44.3 | 126.0 | 0.891 |

| Height (cm) | 60 | 158.6 | 157.0 | 144.5 | 177.0 | 30 | 160.2 | 160.0 | 150.0 | 174.0 | 0.217 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 60 | 31.6 | 31.2 | 21.6 | 49.8 | 30 | 31.1 | 30.2 | 19.7 | 48.0 | 0.626 |

| Number of gestational weeks | 60 | 33.4 | 34.0 | 27.0 | 39.0 | 30 | 25.3 | 25.5 | 17.0 | 32.0 | 0.000 |

| Number of live births | 42 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 30 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 0.008 |

| Number of stillbirths | 6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 20 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.752 |

| Miscarriages | 29 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 17 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 9.0 | 0.065 |

| Live births less than 38 weeks of gestational age | 5 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 12 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.249 |

| Number of amalgam fillings | 41 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 12.0 | 20 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 0.224 |

| Gestational age (weeks) at delivery | 60 | 38.3 | 38.0 | 34.0 | 41.0 | 30 | 34.2 | 35.0 | 29.0 | 38.0 | 0.000 |

| Newborn’s Weight (Kg) | 55 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 4.3 | 23 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 0.000 |

| Newborn’s height (cm) | 41 | 50.0 | 51.0 | 44.0 | 57.0 | 12 | 45.2 | 45.5 | 38.0 | 50.0 | 0.003 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 22 | 35.7 | 34.5 | 32.0 | 47.0 | 10 | 32.8 | 32.3 | 30.0 | 36.5 | 0.000 |

| Crown–heel length (cm) | 39 | 49.9 | 50.0 | 44.0 | 57.0 | 12 | 45.2 | 45.5 | 38.0 | 50.0 | 0.000 |

| Apgar 1-min score | 49 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 9.0 | 20 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 9.0 | 0.001 |

| Apgar 5-min score | 49 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 20 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 0.001 |

| Infant’s body weight (kg) at 2 months | 47 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 18 | 8.4 | 6.0 | 4.3 | 50.0 | 0.139 |

| Infant’s height (cm) at 2 months | 36 | 59.5 | 58.5 | 49.0 | 75.5 | 13 | 58.3 | 60.0 | 50.0 | 66.0 | 0.592 |

| ASQ-3-Communication | 55 | 49.18 | 50.0 | 20.0 | 60.0 | 19 | 50.53 | 50.0 | 30.0 | 60.0 | 0.575 |

| ASQ-3-Gross motor | 54 | 51.30 | 52.5 | 25.0 | 60.0 | 19 | 51.84 | 60.0 | 30.0 | 60.0 | 0.527 |

| ASQ-3-Fine motor | 55 | 51.64 | 55.0 | 30.0 | 60.0 | 19 | 47.37 | 50.0 | 30.0 | 60.0 | 0.229 |

| ASQ-3-Problem-solving | 55 | 54.55 | 60.0 | 20.0 | 60.0 | 19 | 52.37 | 55.0 | 20.0 | 60.0 | 0.131 |

| ASQ-3-Personal–social | 55 | 50.00 | 50.0 | 30.0 | 60.0 | 19 | 49.21 | 50.0 | 30.0 | 60.0 | 0.964 |

| Categorical variables | Non-IUBT recipients N (%) | IUBT recipients, N (%) | p-value | ||||||||

| Educational level (≤12/>12 years schooling) | 6 (6.7%)/54 (60%) | 9 (10%)/21 (23.3%) | 0.032 | ||||||||

| Work status (Current/Past and/or Never) | 28 (31.1%)/32 (35.6%) | 7 (7.8%)/23 (25.6%) | 0.042 | ||||||||

| Family income in SR (≤10,000/>10,000/Unknown or refused) | 17 (18.9%)/27 (30%)/16 (17.8%) | 6 (6.7%)/12 (13.3%)/12 (13.3%) | 0.406 | ||||||||

| Current pregnancy conceived through in vitro fertilization (Yes/No) | 6 (6.7%)/54 (60%) | 0 (0%)/30 (33.3%) | 0.08 | ||||||||

| Have any children from previous pregnancies experienced neurological problems? (Yes/No) | 1 (1.1%)/58 (65.2%) | 3 (3.4%)/27 (30.3%) | 0.109 | ||||||||

| Health status (Diseased/None) | 35 (38.9%)/25 (27.8%) | 18 (20%)/12 (13.3%) | 0.532 | ||||||||

| Smoking cigarettes and/or water pipes (Yes/No) | 2 (2.2%)/58 (64.4%) | 1 (1.1%)/29 (32.2%) | 0.709 | ||||||||

| Living with a smoker, including spouse or family member (Yes/No) | 15 (16.7%)/45 (50%) | 13 (14.4%)/17 (18.9%) | 0.077 | ||||||||

| Living in a polluted area (Yes/No) | 12 (13.3%)/48 (53.3%) | 9 (10%)/21 (23.3%) | 0.290 | ||||||||

| Dental amalgam (Yes/No) | 43 (47.8%)/17 (18.9%) | 20 (22.2%)/10 (11.1%) | 0.626 | ||||||||

| Seafood intake (Yes/No) | 51 (56.7%)/9 (10%) | 125 (27.8%)/5 (5.6%) | 0.837 | ||||||||

| Seafood frequency (Weekly or monthly/Seldom) | 38 (50%)/13 (17.1%) | 19 (25%)/6 (7.9%) | 0.888 | ||||||||

| Newborn gender (Female/Male) | 23 (20.1%)/34 (40%) | 15 (17.6%)/13 (15.3%) | 0.249 | ||||||||

| b | |||||||||||

| Maternal Exposure | No IUBT Recipients | IUBT Recipients | p-Value | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | ||

| Mercury levels in the blood—third trimester (µg/L) | 60 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 2.15 | 29 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 1.07 | 0.993 |

| Cadmium levels in blood—third trimester (µg/L) | 60 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 4.82 | 29 | 0.82 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 3.53 | 0.386 |

| Lead levels in blood—third trimester (µg/L) | 60 | 6.04 | 3.94 | 0.02 | 82.42 | 29 | 5.03 | 4.26 | 0.72 | 19.57 | 0.766 |

| Arsenic levels in blood—third trimester (µg/L) | 60 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 1.70 | 29 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.86 | 0.944 |

| Fetal exposure | No IUBT recipients | IUBT recipients | p-value | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | ||

| Mercury levels in cord blood (µg/L) | 40 | 1.01 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 4.72 | 21 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 2.03 | 0.129 |

| Cadmium levels in cord blood (µg/L) | 40 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 21 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 2.37 | 0.003 |

| Lead levels in cord blood (µg/L) | 40 | 3.88 | 3.21 | 1.55 | 9.29 | 21 | 4.27 | 4.35 | 0.23 | 12.05 | 0.820 |

| Arsenic levels in cord blood (µg/L) | 40 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 2.54 | 21 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 3.56 | 0.132 |

| Blood transfusion exposure | No IUBT recipients | IUBT recipients | p-value | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | N * | Mean | Median | Min | Max | ||

| Mercury in the blood transfusion (µg/L) | 29 | 1.516 | 0.746 | 0.001 | 28.225 | NA | |||||

| Cadmium in blood transfusion (µg/L) | 29 | 0.924 | 0.749 | 0.001 | 3.947 | NA | |||||

| Lead in blood transfusion (µg/L) | 29 | 14.690 | 12.798 | 3.116 | 41.439 | NA | |||||

| Arsenic in blood transfusion (µg/L) | 29 | 0.746 | 0.436 | 0.0007 | 8.423 | Na | |||||

| Matrix | Models | Communication | Gross Motor | Fine Motor | Problem-Solving | Personal–Social | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |||||||

| Maternal | Mercury | 0.001 | −0.030 | 0.033 | −0.005 | −0.034 | 0.024 | 0.019 | −0.01 | 0.047 | −0.002 | −0.035 | 0.031 | −0.031 ** | −0.056 | −0.007 |

| Cadmium | −0.006 | −0.047 | 0.036 | −0.005 | −0.043 | 0.032 | 0.022 | −0.016 | 0.06 | −0.039 *** | −0.082 | 0.004 | −0.014 | −0.048 | 0.019 | |

| Lead | 0.007 | −0.044 | 0.058 | −0.011 | −0.058 | 0.035 | −0.014 | −0.061 | 0.033 | 0.045 *** | −0.008 | 0.097 | 0.019 | −0.023 | 0.06 | |

| Arsenic | 0.007 | −0.036 | 0.05 | 0.009 | −0.03 | 0.048 | 0.017 | −0.023 | 0.056 | −0.017 | −0.063 | 0.028 | −0.015 | −0.05 | 0.02 | |

| PC1 (mercury and arsenic) | 0.007 | −0.050 | 0.063 | 0.005 | −0.047 | 0.056 | 0.031 | −0.021 | 0.083 | −0.018 | −0.078 | 0.042 | −0.045 *** | −0.090 | 0.001 | |

| PC2 (lead & cadmium) | 0.008 | −0.052 | 0.067 | −0.01 | −0.064 | 0.044 | −0.022 | −0.077 | 0.033 | 0.069 ** | 0.008 | 0.129 | 0.011 | −0.037 | 0.060 | |

| Cord blood | Mercury | −0.018 | −0.071 | 0.035 | −0.011 | −0.06 | 0.038 | 0.004 | −0.051 | 0.06 | −0.049 | −0.113 | 0.016 | −0.028 | −0.073 | 0.016 |

| Cadmium | −0.024 | −0.065 | 0.017 | −0.019 | −0.057 | 0.019 | −0.002 | −0.045 | 0.042 | 0.01 | −0.043 | 0.062 | −0.007 | −0.042 | 0.029 | |

| Lead | −0.036 | −0.156 | 0.083 | 0.051 | −0.058 | 0.161 | 0.107 *** | −0.012 | 0.227 | 0.047 | −0.102 | 0.196 | 0.03 | −0.072 | 0.132 | |

| Arsenic | 0.005 | −0.02 | 0.029 | −0.006 | −0.028 | 0.017 | −0.003 | −0.028 | 0.023 | −0.04 * | −0.068 | −0.012 | 0.002 | −0.019 | 0.023 | |

| PC1 (mercury, cadmium & arsenic) | 0.006 | −0.065 | 0.076 | −0.004 | −0.069 | 0.061 | 0.002 | −0.071 | 0.074 | −0.089 ** | −0.172 | −0.006 | −0.012 | −0.072 | 0.048 | |

| PC2 (lead) | −0.027 | −0.105 | 0.051 | 0.036 | −0.036 | 0.107 | 0.071 *** | 0.072 | −0.007 | 0.041 | −0.056 | 0.138 | 0.014 | −0.053 | 0.081 | |

| Maternal and cord | PC1 (arsenic in maternal, mercury arsenic & cadmium in cord) | 0 | −0.070 | 0.071 | 0 | −0.065 | 0.064 | 0.013 | −0.060 | 0.085 | −0.077 *** | −0.161 | 0.007 | −0.021 | −0.081 | 0.039 |

| PC2 (mercury, lead & cadmium in maternal) | −0.022 | −0.099 | 0.056 | 0.001 | −0.070 | 0.073 | 0.021 | −0.059 | 0.101 | 0.037 | −0.058 | 0.133 | −0.032 | −0.097 | 0.033 | |

| RBC transfusion | a Mercury | −0.001 | −0.144 | 0.142 | −0.116 ** | −0.220 | −0.012 | −0.094 | −0.249 | 0.061 | −0.087 *** | −0.186 | 0.012 | −0.014 | −0.179 | 0.151 |

| a Cadmium | 0.012 | −0.061 | 0.085 | −0.021 | −0.087 | 0.046 | 0.016 | −0.069 | 0.102 | −0.018 | −0.077 | 0.040 | 0.014 | −0.070 | 0.098 | |

| a Lead | 0.338 | −0.199 | 0.875 | −0.006 | −0.549 | 0.537 | 0.530 *** | −0.052 | 1.112 | 0.254 | −0.189 | 0.698 | 0.032 | −0.647 | 0.711 | |

| a Arsenic | 0.008 | −0.055 | 0.071 | −0.045 *** | −0.094 | 0.005 | −0.03 | −0.101 | 0.042 | −0.02 | −0.070 | 0.029 | 0.014 | −0.059 | 0.087 | |

| a PC1 (mercury & arsenic) | 0.021 | −0.155 | 0.196 | −0.138 ** | −0.269 | −0.007 | −0.096 | −0.292 | 0.101 | −0.068 | −0.204 | 0.067 | 0.012 | −0.192 | 0.216 | |

| a PC2 (lead & cadmium) | 0.117 | −0.109 | 0.344 | −0.072 | −0.289 | 0.145 | 0.179 | −0.075 | 0.433 | −0.01 | −0.206 | 0.186 | 0.058 | −0.218 | 0.333 | |

| All matrices | PC1 (mercury & arsenic) | 0.063 | −0.296 | 0.421 | −0.18 | −0.568 | 0.209 | 0.076 | −0.428 | 0.579 | 0.037 | −0.287 | 0.361 | 0.002 | −0.475 | 0.479 |

| PC2 (lead & cadmium) | −0.083 | −0.440 | 0.274 | −0.163 | −0.574 | 0.248 | −0.093 | −0.601 | 0.414 | −0.104 | −0.406 | 0.197 | −0.023 | −0.507 | 0.462 | |

| Models | Communication | Gross Motor | Fine Motor | Problem-Solving | Personal–Social | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |||||||

| Maternal blood | Mercury | 0.003 | −0.029 | 0.035 | −0.008 | −0.037 | 0.021 | 0.015 | −0.014 | 0.044 | −0.003 | −0.037 | 0.031 | −0.035 ** | −0.06 | −0.01 |

| Cadmium | −0.005 | −0.047 | 0.036 | −0.005 | −0.043 | 0.032 | 0.022 | −0.016 | 0.059 | −0.039 *** | −0.082 | 0.004 | −0.014 | −0.048 | 0.019 | |

| Lead | 0.006 | −0.046 | 0.057 | −0.009 | −0.055 | 0.038 | −0.01 | −0.057 | 0.036 | 0.046 *** | −0.007 | 0.1 | 0.021 | −0.02 | 0.063 | |

| Arsenic | 0.011 | −0.034 | 0.055 | 0.003 | −0.037 | 0.043 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.021 | −0.068 | 0.025 | −0.022 | −0.058 | 0.014 | |

| PC1 (mercury & arsenic) | 0.011 | −0.048 | 0.070 | −0.004 | −0.057 | 0.049 | 0.024 | −0.031 | 0.076 | −0.024 | −0.086 | 0.039 | −0.055 ** | −0.101 | −0.009 | |

| PC2 (lead & cadmium) | 0.007 | −0.053 | 0.067 | −0.008 | −0.062 | 0.046 | −0.019 | −0.073 | 0.035 | 0.07 ** | 0.009 | 0.131 | 0.013 | −0.035 | 0.062 | |

| Cord blood | Mercury | −0.012 | −0.066 | 0.042 | −0.018 | −0.068 | 0.031 | −0.007 | −0.061 | 0.047 | −0.063 ** | −0.125 | 0 | −0.03 | −0.076 | 0.016 |

| Cadmium | −0.037 *** | −0.079 | 0.006 | −0.012 | −0.052 | 0.029 | 0.014 | −0.03 | 0.058 | 0.028 | −0.025 | 0.081 | −0.006 | −0.045 | 0.032 | |

| Lead | −0.021 | −0.143 | 0.100 | 0.037 | −0.074 | 0.148 | 0.085 | −0.033 | 0.204 | 0.02 | −0.128 | 0.168 | 0.03 | −0.076 | 0.135 | |

| Arsenic | 0.006 | −0.019 | 0.03 | −0.006 | −0.029 | 0.016 | −0.004 | −0.028 | 0.02 | −0.041 * | −0.068 | −0.015 | 0.002 | −0.019 | 0.023 | |

| PC1 (mercury, cadmium & arsenic) | 0.017 | −0.055 | 0.089 | −0.015 | −0.081 | 0.050 | −0.016 | −0.087 | 0.056 | −0.112 * | −0.192 | −0.033 | −0.014 | −0.076 | 0.049 | |

| PC2 (lead) | −0.016 | −0.096 | 0.064 | 0.025 | −0.048 | 0.098 | 0.055 | −0.023 | 0.134 | 0.021 | −0.076 | 0.119 | 0.013 | −0.057 | 0.083 | |

| Maternal and cord | PC1 (arsenic in maternal, mercury in cord, arsenic & cadmium) | 0.011 | −0.060 | 0.083 | −0.012 | −0.077 | 0.054 | −0.004 | −0.076 | 0.067 | −0.101 ** | −0.182 | −0.019 | −0.023 | −0.085 | 0.039 |

| PC2 (mercury, lead & cadmium in maternal) | −0.013 | −0.091 | 0.066 | −0.009 | −0.081 | 0.063 | 0.006 | −0.072 | 0.085 | 0.022 | −0.073 | 0.117 | −0.034 | −0.101 | 0.033 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Saleh, I.; Alnuwaysir, H.; Gheith, M.; Al-Rouqi, R.; Aldhalaan, H.; Alismail, E.; Tulbah, M. Prenatal Exposure to Toxic Metals and Early Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Following Intrauterine Blood Transfusion: A Prospective Cohort Study. Toxics 2025, 13, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121055

Al-Saleh I, Alnuwaysir H, Gheith M, Al-Rouqi R, Aldhalaan H, Alismail E, Tulbah M. Prenatal Exposure to Toxic Metals and Early Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Following Intrauterine Blood Transfusion: A Prospective Cohort Study. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121055

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Saleh, Iman, Hissah Alnuwaysir, Mais Gheith, Reem Al-Rouqi, Hesham Aldhalaan, Eiman Alismail, and Maha Tulbah. 2025. "Prenatal Exposure to Toxic Metals and Early Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Following Intrauterine Blood Transfusion: A Prospective Cohort Study" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121055

APA StyleAl-Saleh, I., Alnuwaysir, H., Gheith, M., Al-Rouqi, R., Aldhalaan, H., Alismail, E., & Tulbah, M. (2025). Prenatal Exposure to Toxic Metals and Early Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Following Intrauterine Blood Transfusion: A Prospective Cohort Study. Toxics, 13(12), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121055