Bioinformatic Evidence Suggesting a Dopaminergic-Related Molecular Association Between GenX Exposure and Major Depressive Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Acquisition of MDD, Dopamine, and GenX-Related Genes

2.2. Hub Gene Screening Based on Machine Learning

2.3. Diagnostic Performance Evaluation of Hub Genes

2.4. Genome-Wide Visualization and Functional Enrichment of Hub Genes

2.5. Immune Infiltration Correlation Analysis of Hub Genes

2.6. GeneMANIA-Based Functional Association and Biological Clustering of Hub Genes

2.7. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3. Results

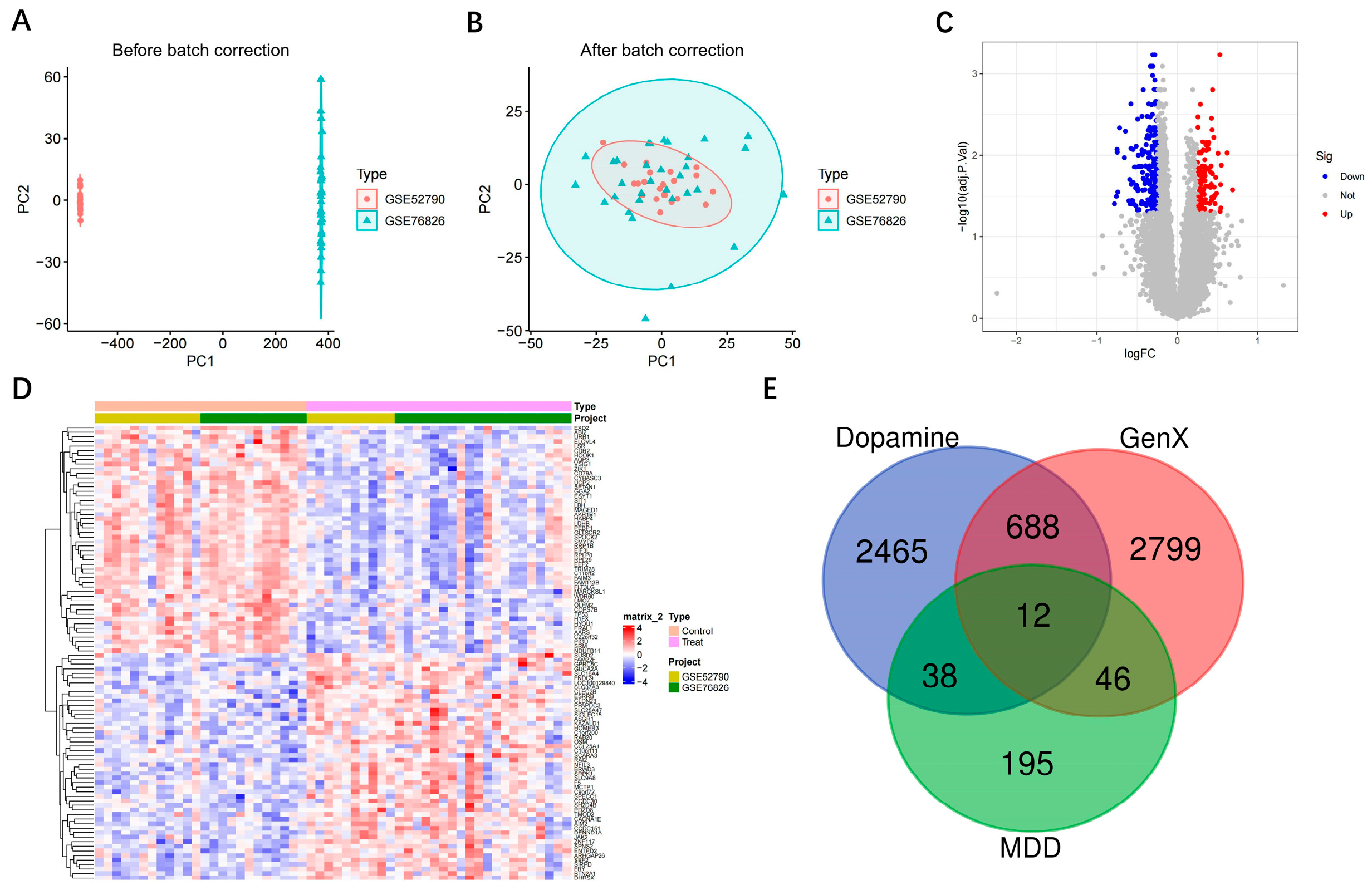

3.1. Intersection of MDD, Dopamine and GenX-Related Genes

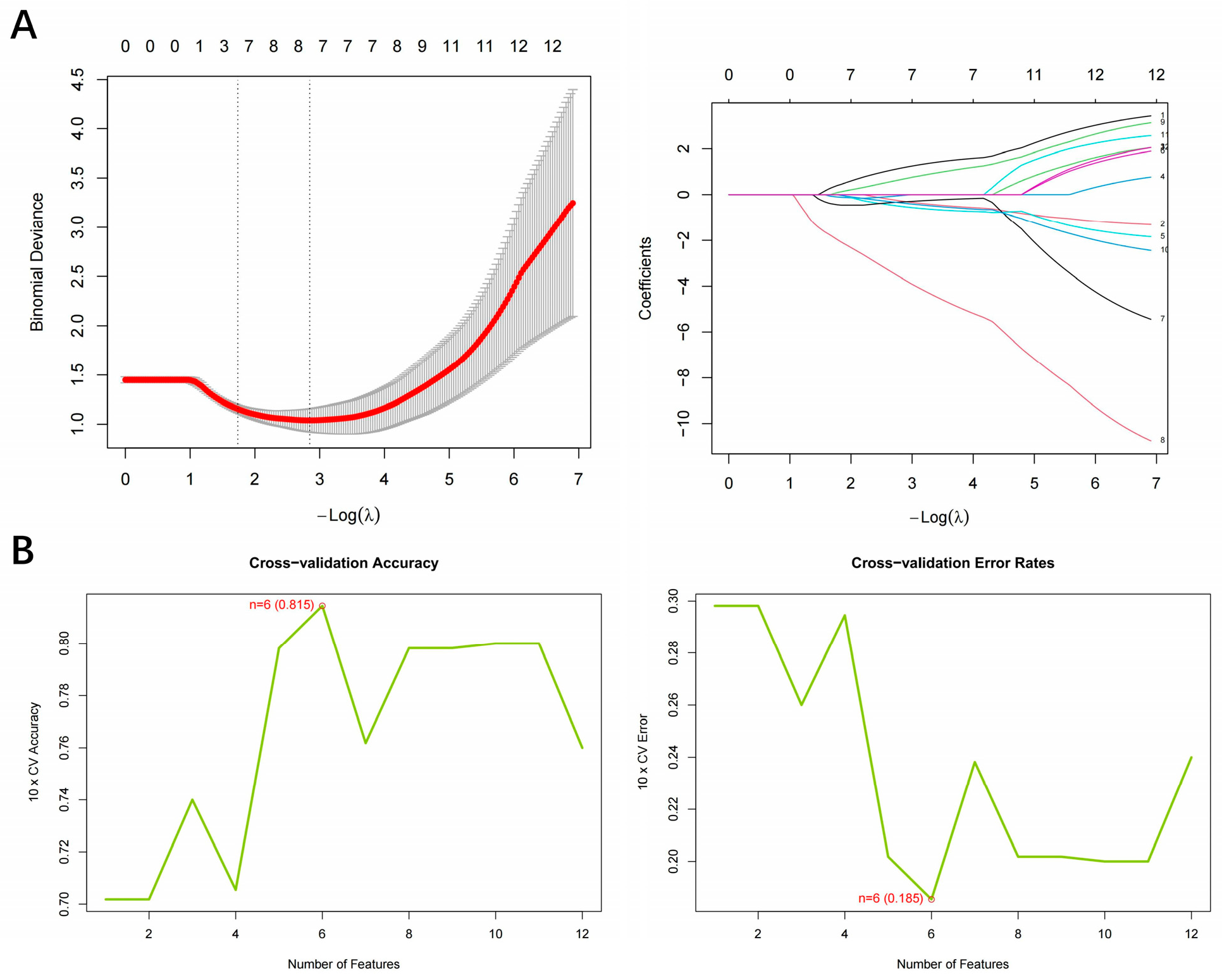

3.2. Identification of Hub Gene Screening Based on Machine Learning

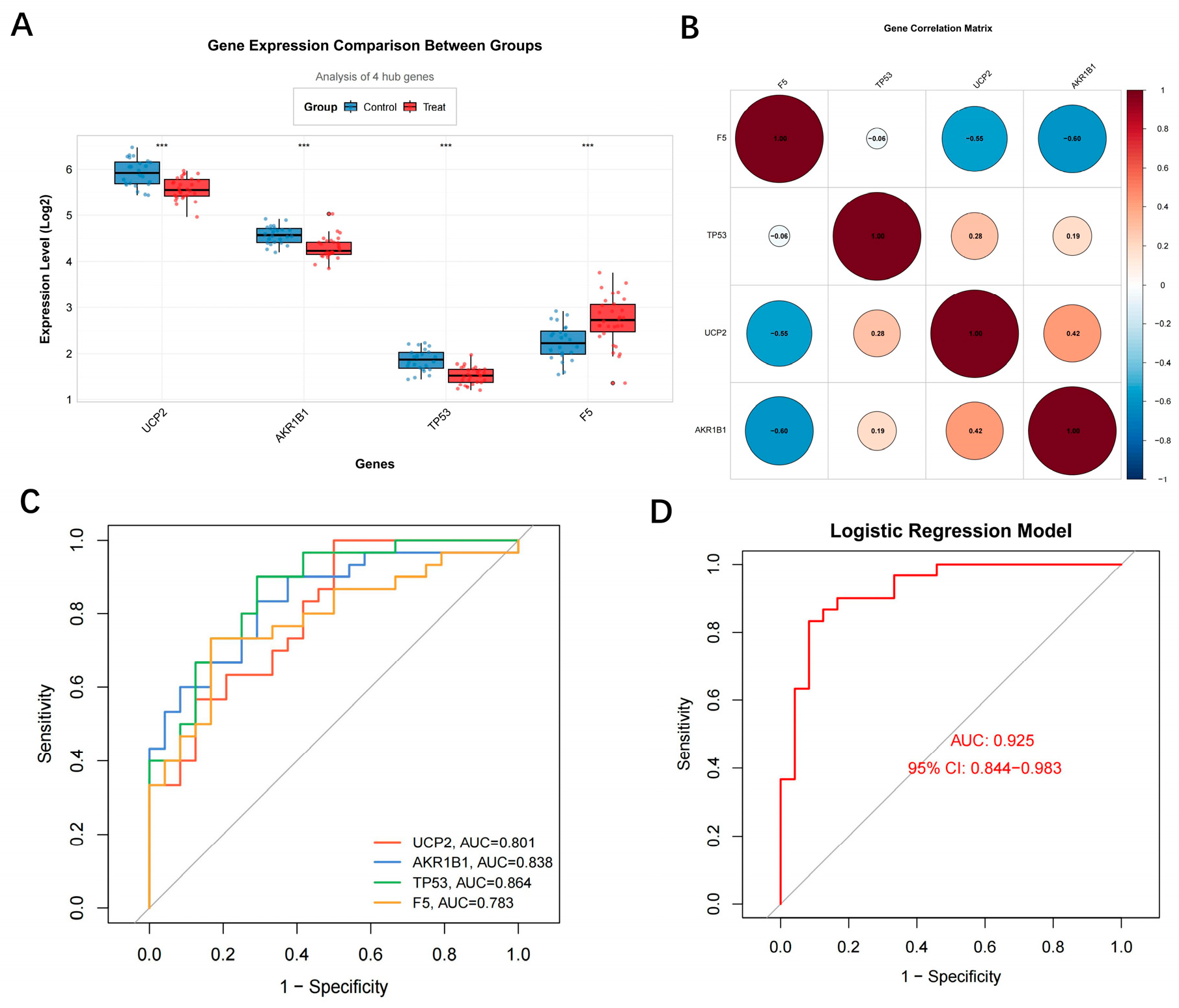

3.3. Diagnostic Performance and Associated Features of Hub Genes

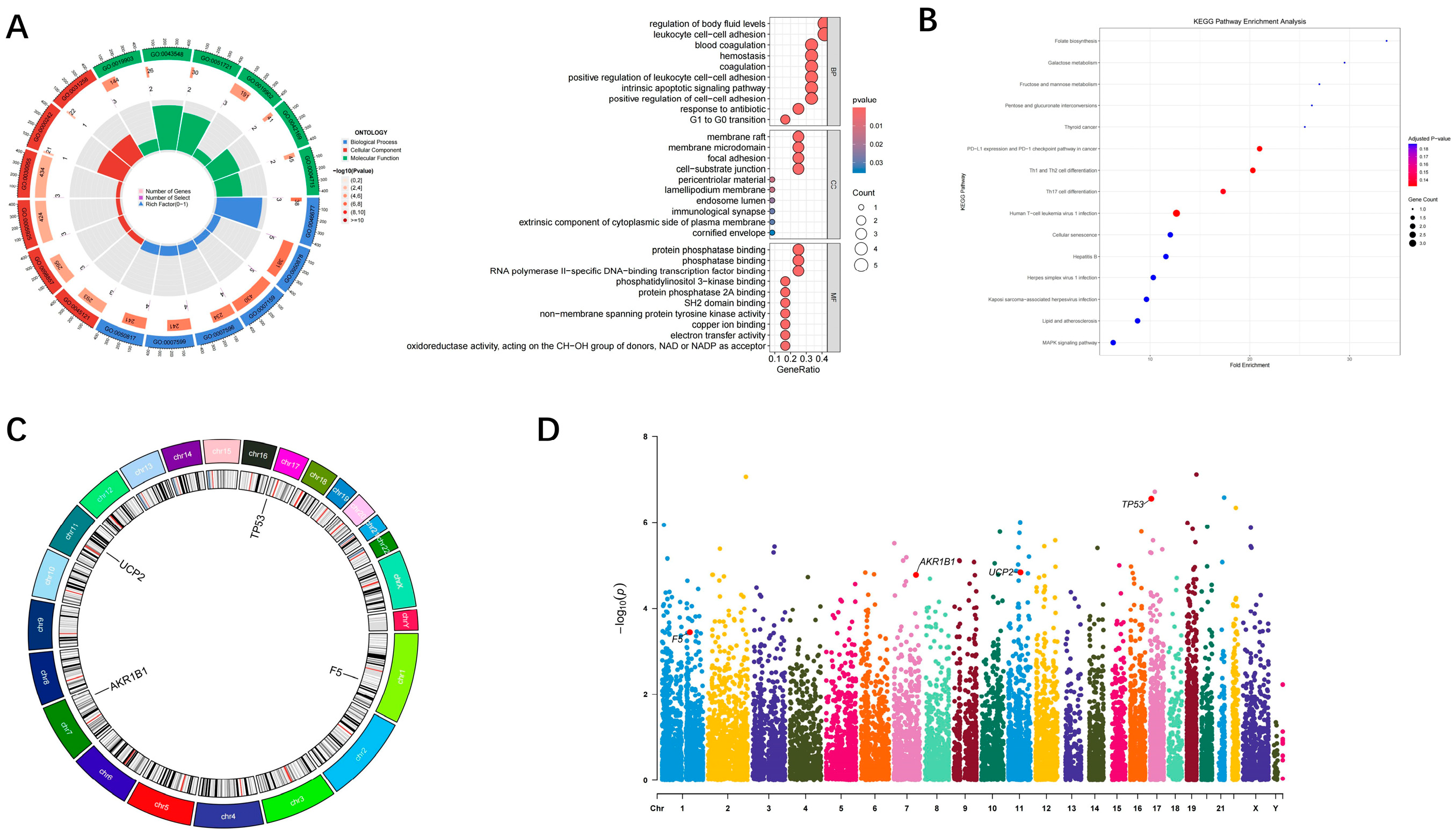

3.4. Genome-Wide Visualization and Functional Enrichment of Hub Genes

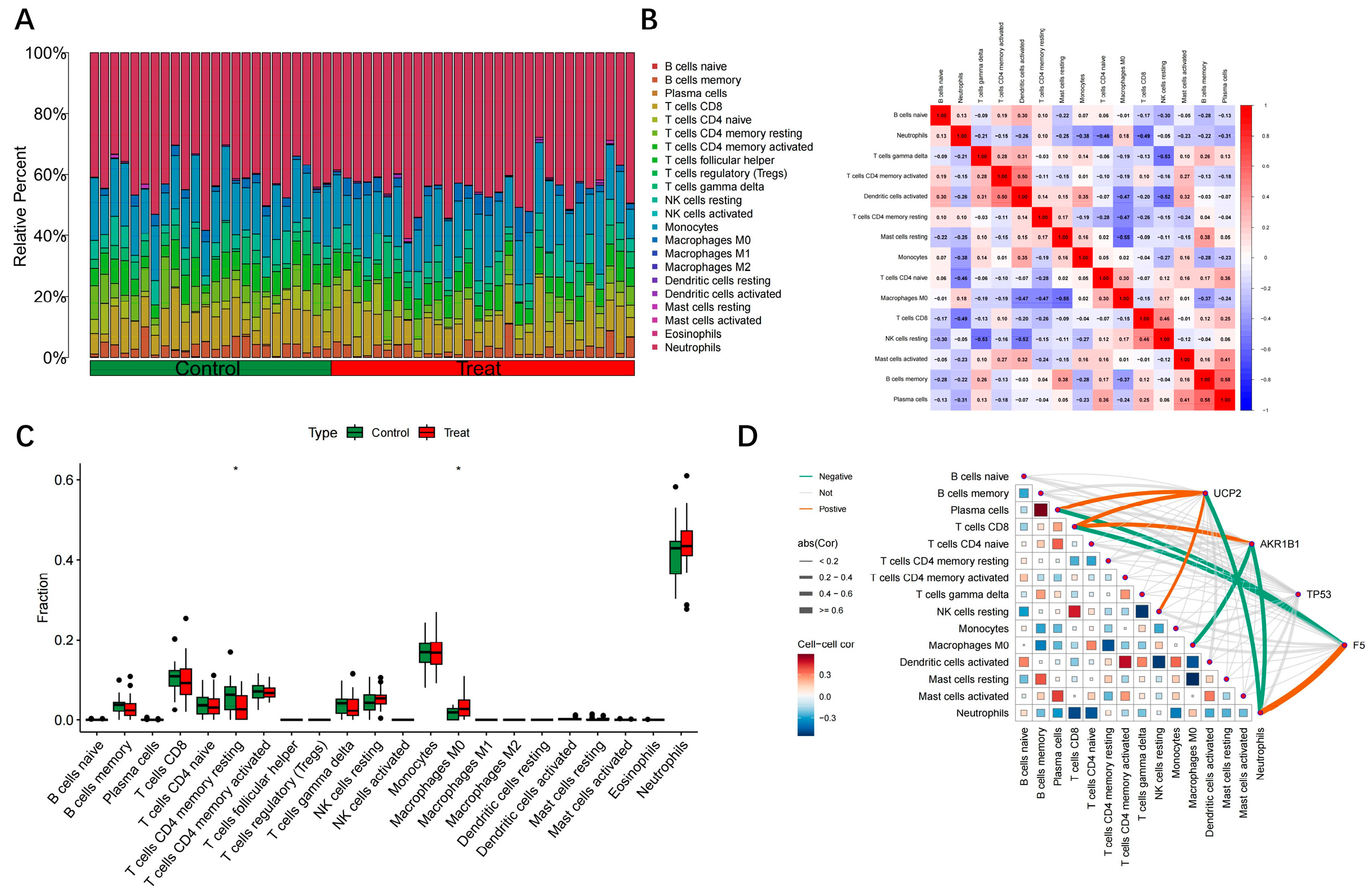

3.5. Analysis of Hub Gene Correlation with Immune Infiltration

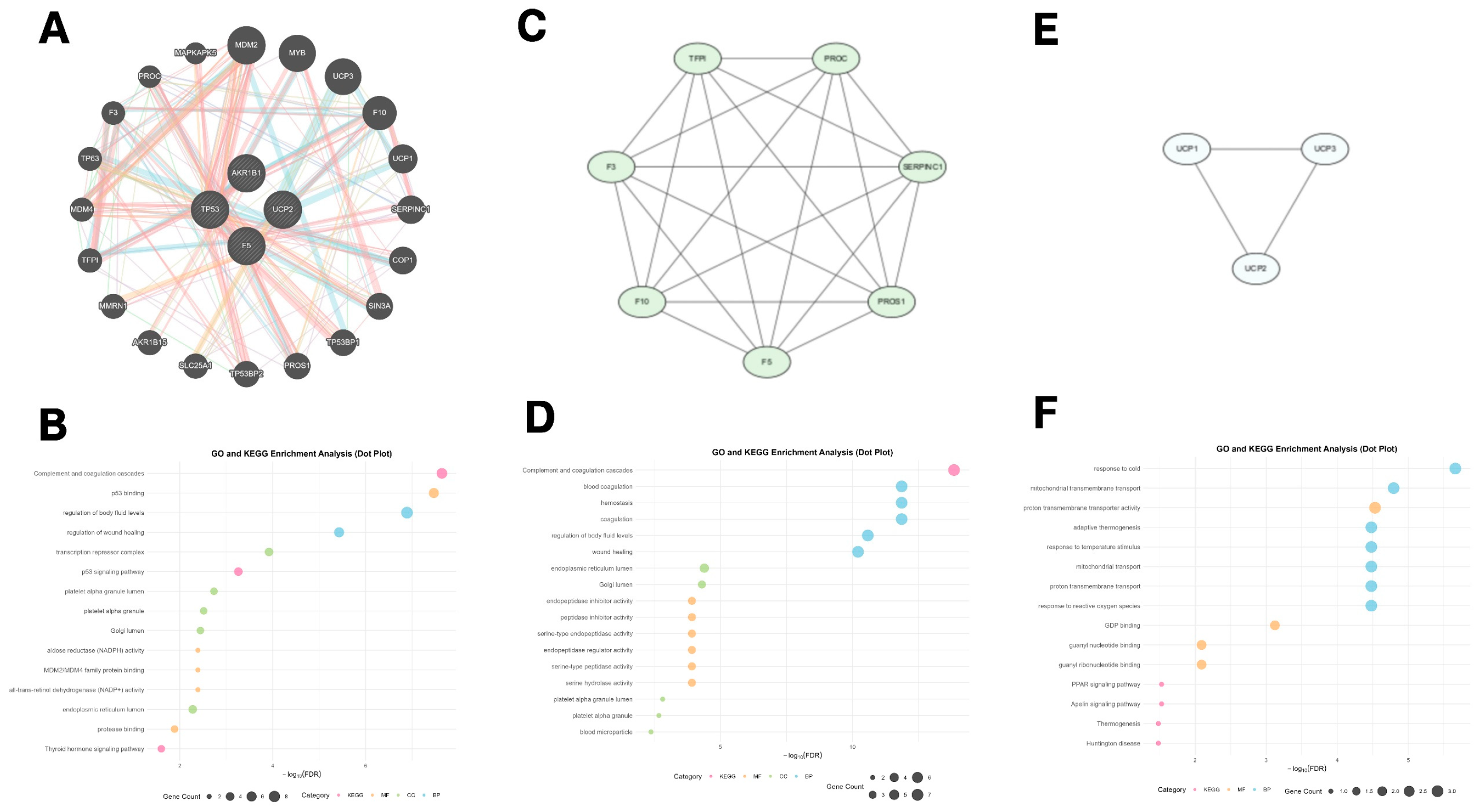

3.6. GeneMANIA Functional Association and Biological Function Clustering of Hub Genes

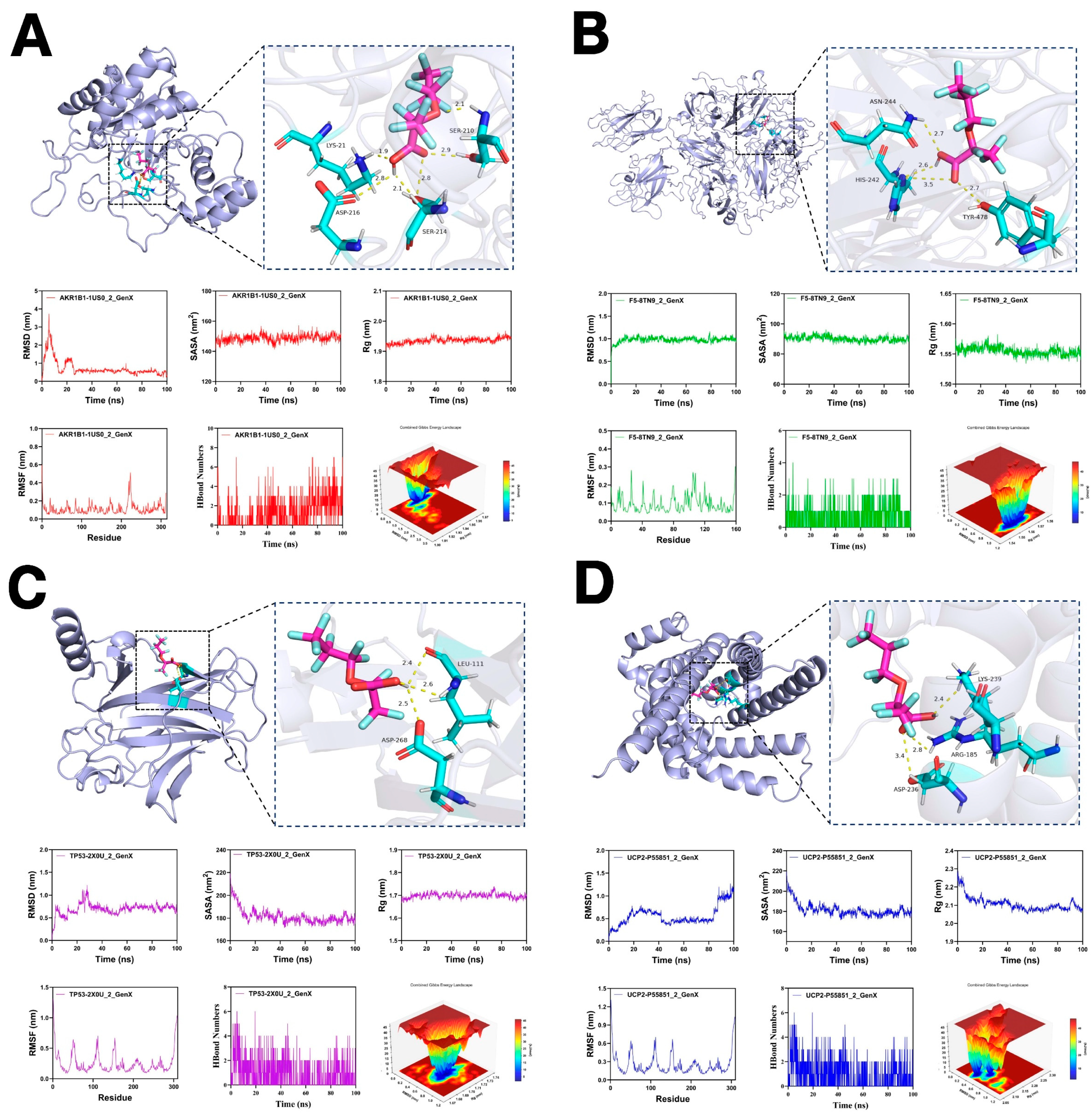

3.7. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations

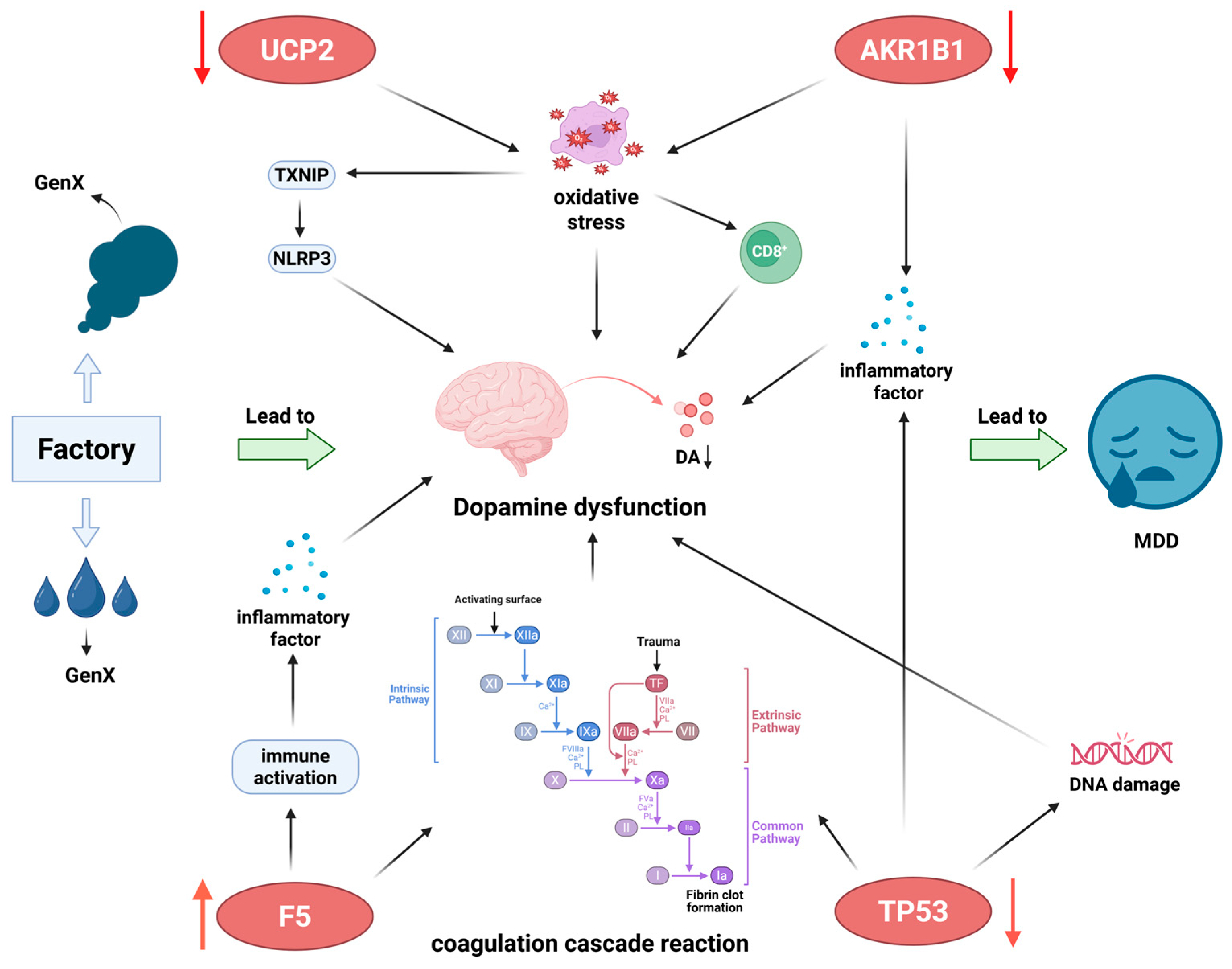

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krishnan, V.; Nestler, E.J. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 2008, 455, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Z.Y.; Qin, Z.Z.; Ye, J.J.; Hu, X.X.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Zheng, P.; Lu, Q.S.; Li, Q.; Tang, X.Y. The long-term spatio-temporal trends in burden and attributable risk factors of major depressive disorder at global, regional and national levels during 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for GBD 2019. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2024, 33, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ye, C.; Xin, Q.; Si, T. Major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior in Chinese population: A scoping review of current evidence on disease assessment, burden, treatment and risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Garshick, E.; Si, F.; Tang, Z.; Lian, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Koutrakis, P. Environmental Toxicant Exposure and Depressive Symptoms. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2420259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; de Voogt, P.; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; van Leeuwen, S.P. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: Terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2011, 7, 513–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharal, B.; Ruchitha, C.; Kumar, P.; Pandey, R.; Rachamalla, M.; Niyogi, S.; Naidu, R.; Kaundal, R.K. Neurotoxicity of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: Evidence and future directions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Xuan, L.; Zakaly, H.M.H.; Markovic, V.; Miszczyk, J.; Guan, H.; Zhou, P.K.; Huang, R. Association between per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and depression in U.S. adults: A cross-sectional study of NHANES from 2005 to 2018. Environ. Res. 2023, 238 Pt 2, 117188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, H.; Tanghal, R.B.; Chatzi, L.; Goodrich, J.A.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Aung, M. Metabolic Perturbations Associated with both PFAS Exposure and Perinatal/Antenatal Depression in Pregnant Individuals: A Meet-in-the-Middle Scoping Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, H.; Abbas, T.; Ok, Y.S.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Bhatnagar, A.; Khan, E. Corrigendum to "GenX is not always a better fluorinated organic compound than PFOA: A critical review on aqueous phase treatability by adsorption and its associated cost" [Water Research 205 (2021) 117683]. Water Res. 2025, 268 Pt B, 122786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, F.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, N.; Hu, J.; Dai, J.; Pan, Y. Nationwide distribution of perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids in Chinese diets: An emerging concern. Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conley, J.M.; Lambright, C.S.; Evans, N.; Strynar, M.J.; McCord, J.; McIntyre, B.S.; Travlos, G.S.; Cardon, M.C.; Medlock-Kakaley, E.; Hartig, P.C.; et al. Adverse Maternal, Fetal, and Postnatal Effects of Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Dimer Acid (GenX) from Oral Gestational Exposure in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 37008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, M.; Li, J. GenX caused liver injury and potential hepatocellular carcinoma of mice via drinking water even at environmental concentration. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xie, J.; Zhao, H.; Sanchez, O.; Zhao, X.; Freeman, J.L.; Yuan, C. Pre-differentiation GenX exposure induced neurotoxicity in human dopaminergic-like neurons. Chemosphere 2023, 332, 138900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Salah, A.; Cesur, M.F.; Anchan, A.; Ay, M.; Langley, M.R.; Shah, A.; Reina-Gonzalez, P.; Strazdins, R.; Çakır, T.; Sarkar, S. Comparative Proteomics Highlights that GenX Exposure Leads to Metabolic Defects and Inflammation in Astrocytes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 20525–20539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Zhu, G.; Wang, G.; Zhang, F. Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation Potentiate Each Other to Promote Progression of Dopamine Neurodegeneration. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 6137521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dichtl, S.; Haschka, D.; Nairz, M.; Seifert, M.; Volani, C.; Lutz, O.; Weiss, G. Dopamine promotes cellular iron accumulation and oxidative stress responses in macrophages. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 148, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, H.; Huang, H.; Fan, Z. Anti-oxidant mechanisms of Chlorella pyrenoidosa under acute GenX exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 797, 149005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, A.A. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.H.; Grace, A.A. Amygdala-ventral pallidum pathway decreases dopamine activity after chronic mild stress in rats. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 76, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xiang, L.; Sze-Yin Leung, K.; Elsner, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pan, B.; Sun, H.; An, T.; Ying, G.; et al. Emerging contaminants: A One Health perspective. Innovation 2024, 5, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesci, S.; Rubattu, S. UCP2, a Member of the Mitochondrial Uncoupling Proteins: An Overview from Physiological to Pathological Roles. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, L.; Srivastava, R.K.; Kos, F.; Shrikant, P.A. Uncoupling protein 2 regulates metabolic reprogramming and fate of antigen-stimulated CD8+ T cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, R.H.; Wu, F.F.; Lu, M.; Shu, X.D.; Ding, J.H.; Wu, G.; Hu, G. Uncoupling protein 2 modulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in astrocytes and its implications in depression. Redox Biol. 2016, 9, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Han, B.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Ren, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Carbone, M.; Dong, C.; et al. AKR1B1-dependent fructose metabolism enhances malignancy of cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2024, 31, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana, K.V.; Friedrich, B.; Srivastava, S.; Bhatnagar, A.; Srivastava, S.K. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB by hyperglycemia in vascular smooth muscle cells is regulated by aldose reductase. Diabetes 2004, 53, 2910–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Xu, M.X.; Qian, T.Y.; Zhu, S.Z.; Jiang, F.; Liu, Z.X.; Xu, W.S.; Zhou, J.; Xiao, M.B. The AKR1B1 inhibitor epalrestat suppresses the progression of cervical cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 6091–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, H.; Duan, K.; Wushouer, S.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Qin, X. Gene signatures associated with exosomes as diagnostic markers of postpartum depression and their role in immune infiltration. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1542327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, C.D.; Pickup, J.C.; Ismail, K. The link between depression and diabetes: The search for shared mechanisms. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Deshmukh, M. Essential postmitochondrial function of p53 uncovered in DNA damage-induced apoptosis in neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Laverty, D.J.; Talele, S.; Bale, A.; Carlson, B.L.; Porath, K.A.; Bakken, K.K.; Burgenske, D.M.; Decker, P.A.; Vaubel, R.A.; et al. Aberrant ATM signaling and homology-directed DNA repair as a vulnerability of p53-mutant GBM to AZD1390-mediated radiosensitization. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadj5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Evinová, A.; Škereňová, M.; Ondrejka, I.; Lehotský, J. Association of EGF, IGFBP-3 and TP53 Gene Polymorphisms with Major Depressive Disorder in Slovak Population. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 24, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, M.P.; Foury, A.; Dexpert, S.; Cole, S.W.; Beau, C.; Forestier, D.; Ledaguenel, P.; Magne, E.; Capuron, L. Transcriptomic signaling pathways involved in a naturalistic model of inflammation-related depression and its remission. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.P.; Kerschen, E.J.; Basu, S.; Hernandez, I.; Zogg, M.; Jia, S.; Hessner, M.J.; Toso, R.; Rezaie, A.R.; Fernández, J.A.; et al. Coagulation factor V mediates inhibition of tissue factor signaling by activated protein C in mice. Blood 2015, 126, 2415–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, R.; Chapman, J. Inflammation and Coagulation in Neurologic and Psychiatric Disorders. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2025, 51, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, C.C.; Onisiforou, A.; Zanos, P.; Papanicolaou, E.Z. Unraveling the transcriptomic signatures of Parkinson’s disease and major depression using single-cell and bulk data. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1273855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Hu, N.; Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Yang, K.; Sun, T. Dysregulated Coagulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2024, 13, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtblau, N.; Schmidt, F.M.; Schumann, R.; Kirkby, K.C.; Himmerich, H. Cytokines as biomarkers in depressive disorder: Current standing and prospects. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Qu, S. MIF downregulation attenuates neuroinflammation via TLR4/MyD88/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway to protect dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease model. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni, M.; Sagheddu, C.; Serra, V.; Mostallino, R.; Castelli, M.P.; Pisano, F.; Scherma, M.; Fadda, P.; Muntoni, A.L.; Zamberletti, E.; et al. Maternal immune activation impairs endocannabinoid signaling in the mesolimbic system of adolescent male offspring. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 109, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Wang, G.; Cui, Y.; Meng, P.; Hu, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Association between inflammatory cytokines and symptoms of major depressive disorder in adults. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1110775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Zhu, C.; Zheng, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; et al. Inflammatory cytokines, complement factor H and anhedonia in drug-naïve major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 95, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Module | Input Genes (n) | Balancing Method | Selected Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO | 12 | None | 8 |

| SVM-RFE (MinError) | 12 | None | 6 |

| SVM-RFE (One-SE) | 12 | None | 6 |

| SVM-RFE (Balanced) | 12 | None | 10 |

| Gene Symbol | logFC (in MDD) | Adjusted p-Value | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| JAK2 | 0.294 | 9.40 × 10−3 | Non-receptor tyrosine kinase; crucial in cytokine signaling and inflammatory responses, which are implicated in MDD pathophysiology. |

| PHGDH | −0.332 | 4.89 × 10−2 | Key enzyme in serine biosynthesis; links metabolic reprogramming to neuronal function and survival. |

| NT5E (CD73) | −0.747 | 9.19 × 10−3 | Ecto-5′-nucleotidase; regulates purinergic signaling, extracellular adenosine levels, and has roles in immune suppression and neuroinflammation. |

| UCP2 | −0.343 | 4.55 × 10−3 | Mitochondrial uncoupling protein; regulates energy metabolism, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and is neuroprotective. |

| MFHAS1 | −0.273 | 1.62 × 10−2 | Involved in innate immune response and regulation of TLR4 signaling; potential link to neuroinflammation. |

| HSPB1 | −0.275 | 2.45 × 10−2 | Heat shock protein; functions as a molecular chaperone, protects against oxidative and proteotoxic stress. |

| AKR1B1 | −0.278 | 4.62 × 10−3 | Aldo-keto reductase; involved in glucose metabolism, oxidative stress response, and synthesis of inflammatory mediators. |

| TP53 | −0.336 | 8.17 × 10−4 | Tumor protein p53; a master regulator of cell cycle, DNA repair, and apoptosis in response to cellular stress. |

| F5 | 0.478 | 1.88 × 10−2 | Coagulation Factor V; a central player in the coagulation cascade, linking hemostasis to inflammatory processes. |

| DPP4 | −0.445 | 1.37 × 10−2 | Dipeptidyl peptidase−4; cleaves neuroactive peptides including GLP−1, and functions as a T-cell activation antigen. |

| LCK | −0.295 | 1.11 × 10−2 | Lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase; essential for T-cell receptor signaling and adaptive immune activation. |

| ETS1 | −0.344 | 1.35 × 10−2 | Transcription factor; regulates differentiation and function of immune cells, including T and B lymphocytes. |

| JAK2 | 0.294 | 9.40 × 10−3 | Non-receptor tyrosine kinase; crucial in cytokine signaling and inflammatory responses, which are implicated in MDD pathophysiology. |

| PHGDH | −0.332 | 4.89 × 10−2 | Key enzyme in serine biosynthesis; links metabolic reprogramming to neuronal function and survival. |

| NT5E (CD73) | −0.747 | 9.19 × 10−3 | Ecto-5′-nucleotidase; regulates purinergic signaling, extracellular adenosine levels, and has roles in immune suppression and neuroinflammation. |

| MFHAS1 | −0.273 | 1.62 × 10−2 | Involved in innate immune response and regulation of TLR4 signaling; potential link to neuroinflammation. |

| Targets of GenX | Alphafold ID/PDB ID | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| AKR1B1 | 1US0 | −8.2 |

| F5 | 8TN9 | −7.3 |

| TP53 | 2X0U | −5.8 |

| UCP2 | P55851 | −6.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Lu, Y. Bioinformatic Evidence Suggesting a Dopaminergic-Related Molecular Association Between GenX Exposure and Major Depressive Disorder. Toxics 2025, 13, 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121046

Huang X, Wang Y, Zheng Y, Wang W, Lu Y. Bioinformatic Evidence Suggesting a Dopaminergic-Related Molecular Association Between GenX Exposure and Major Depressive Disorder. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121046

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Xiangyuan, Yanyun Wang, Yuqing Zheng, Weiguang Wang, and Ying Lu. 2025. "Bioinformatic Evidence Suggesting a Dopaminergic-Related Molecular Association Between GenX Exposure and Major Depressive Disorder" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121046

APA StyleHuang, X., Wang, Y., Zheng, Y., Wang, W., & Lu, Y. (2025). Bioinformatic Evidence Suggesting a Dopaminergic-Related Molecular Association Between GenX Exposure and Major Depressive Disorder. Toxics, 13(12), 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121046