Microplastic Toxicity on Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Cells: Evidence from the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

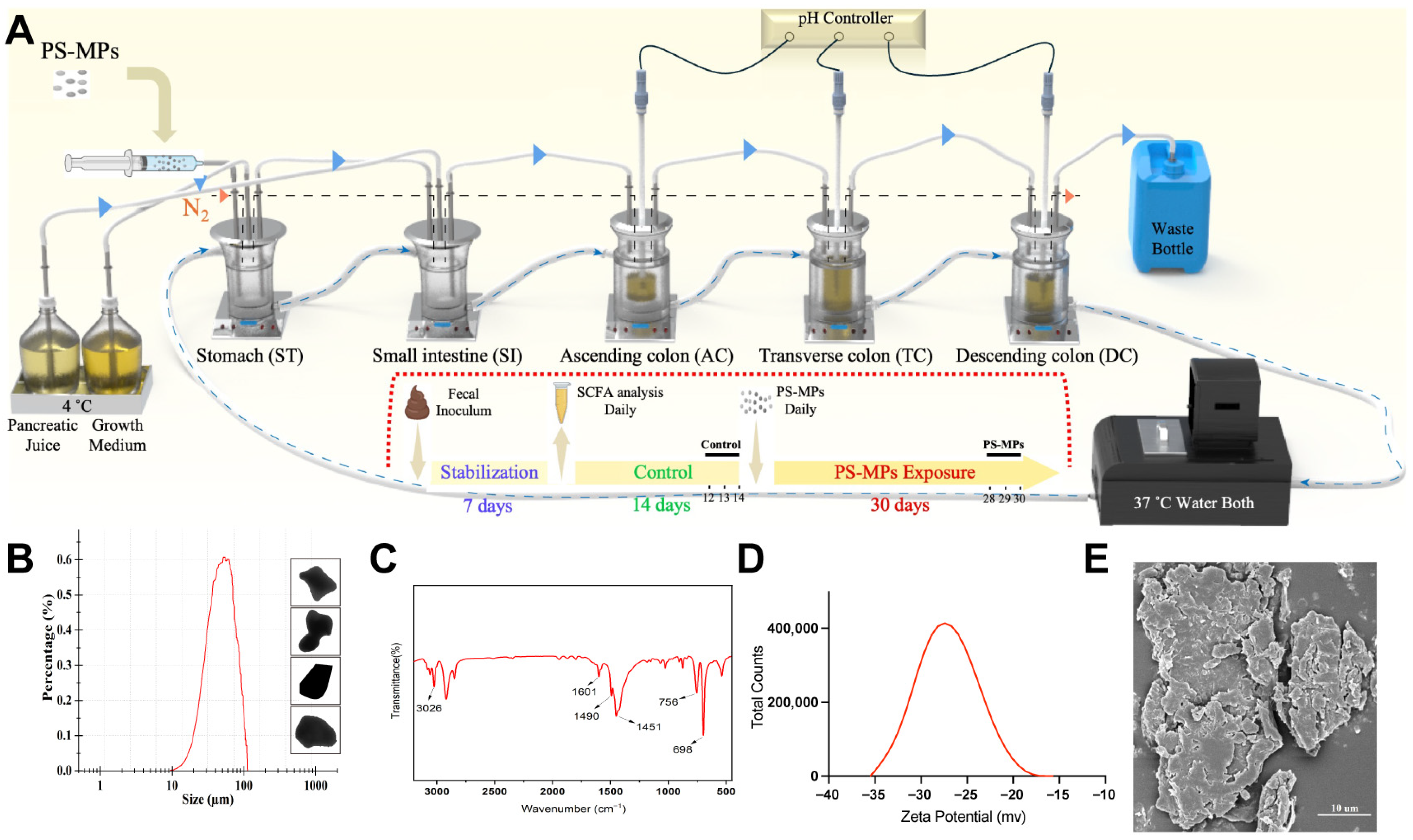

2.1. Design and Establishment of the SHIME System

2.2. Artificial Production and Characterization of PS-MPs

2.3. Fecal Inoculum and Initial Composition of Gut Microbiota

2.4. Timeline of PS-MP Exposure and Sample Collection

2.5. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) Analysis

2.6. 16S rRNA Sequencing and Analysis

2.7. SEM Sample Preparation and Image Acquisition

2.8. Raman Spectroscopy

2.9. Cell Culture

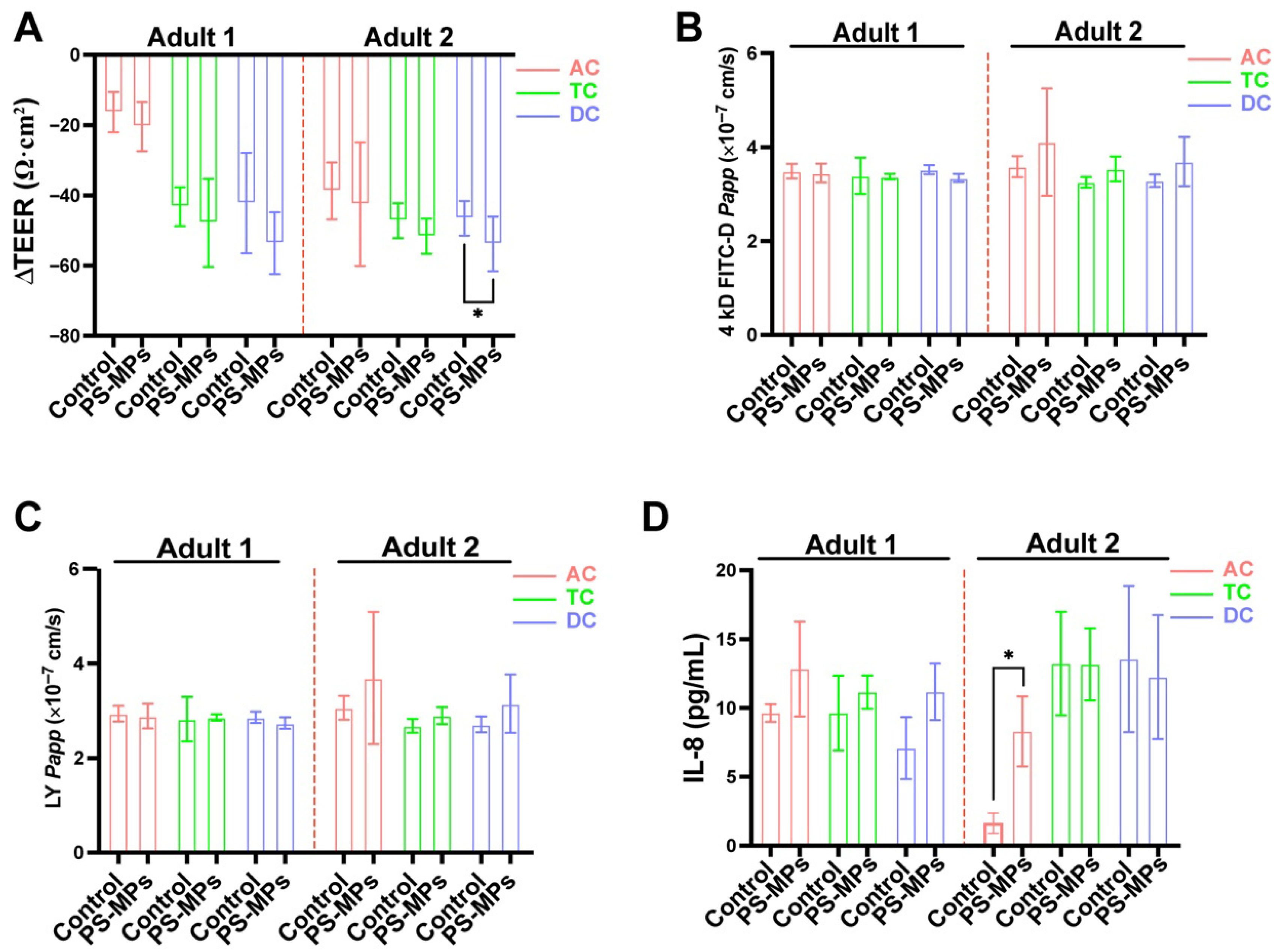

2.10. Cell Viability

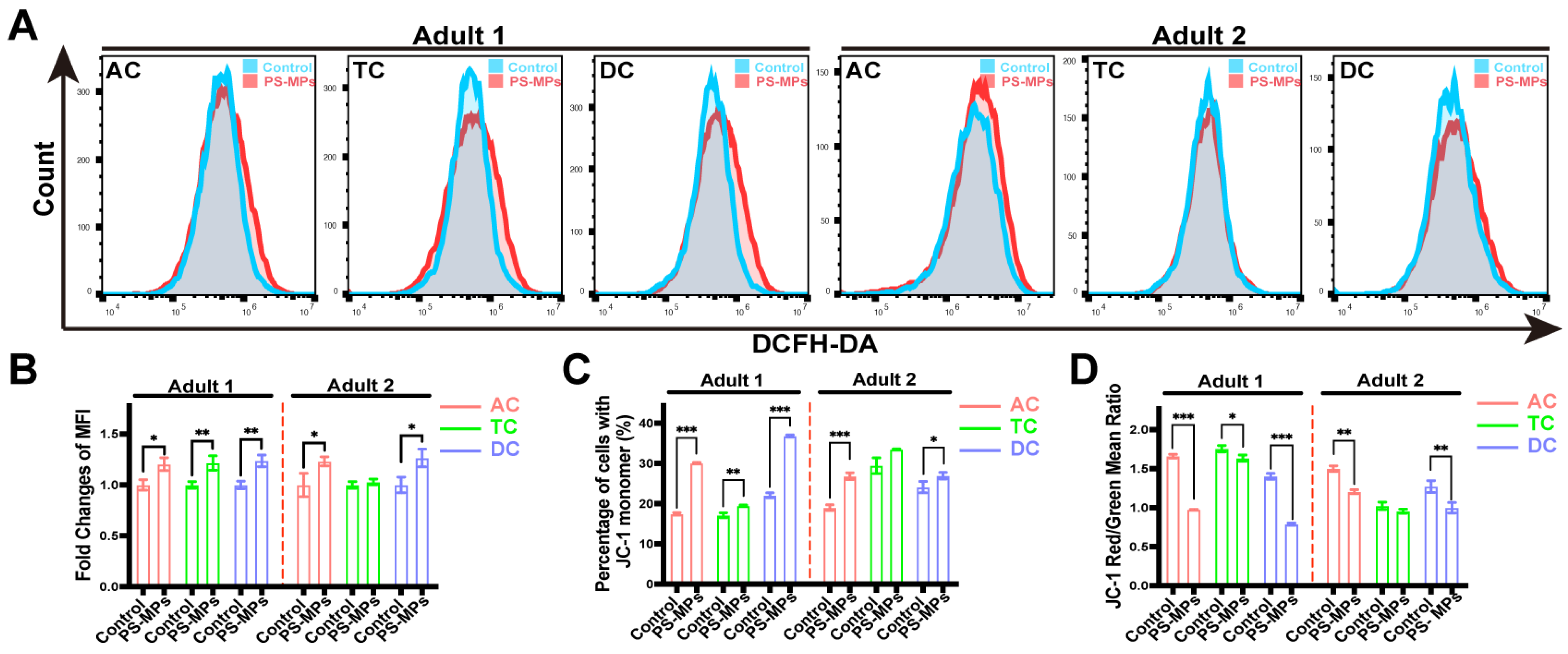

2.11. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation Analysis

2.12. Mitochondria Membrane Potential (MMP) Analysis

2.13. Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) Analysis

2.14. Intestinal Permeability

2.15. ELISA Analysis

2.16. RNA Isolation and Gene Expression Analysis

2.17. Data Analysis

3. Result

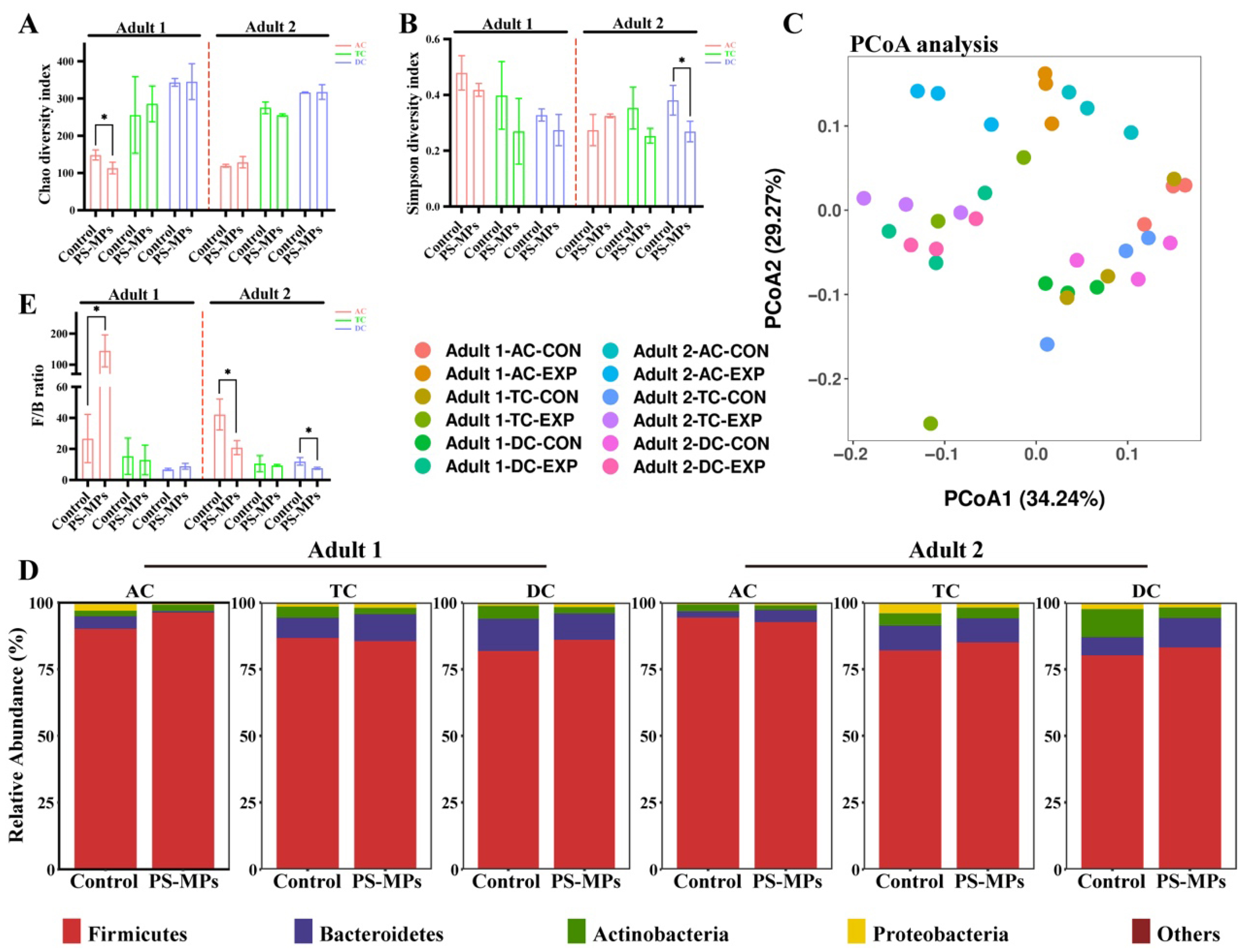

3.1. Effect of PS-MP Exposure on the Gut Microbiota Composition

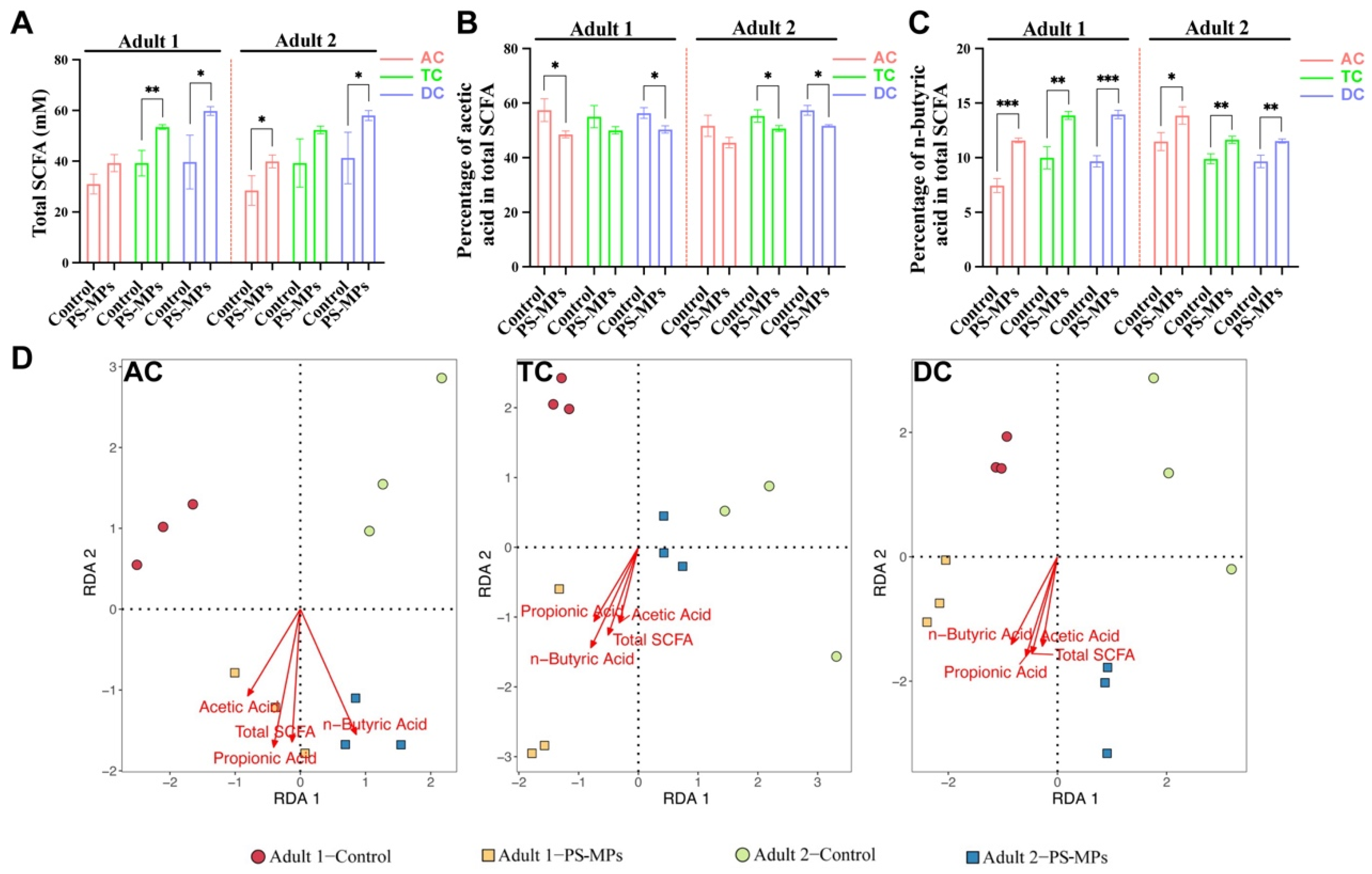

3.2. SCFA Products After PS-MP Exposure

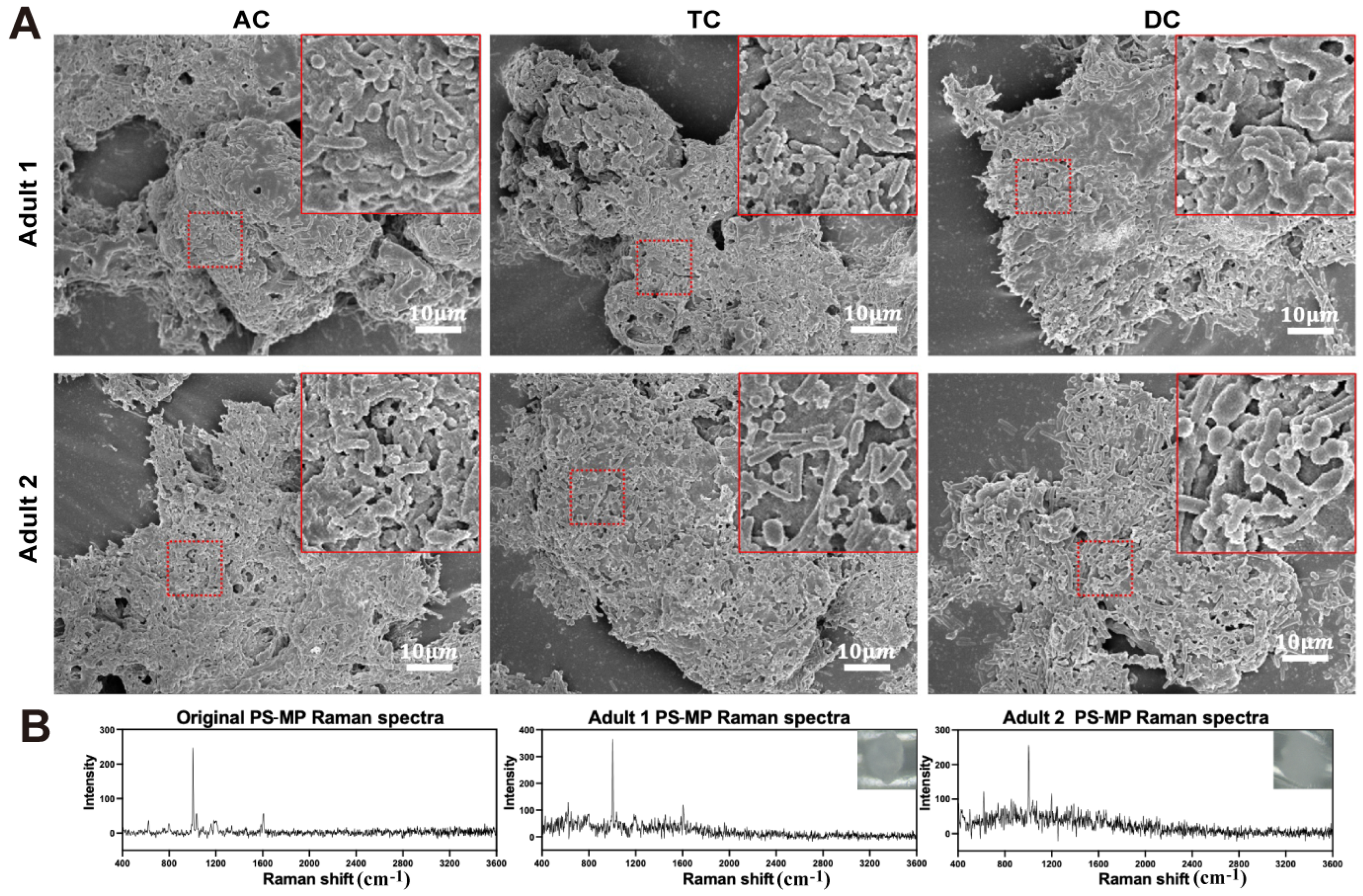

3.3. Interaction Between PS-MPs and Gut Microbiota in the SHIME System

3.4. Effects of SHIME Supernatants on Caco-2/HT29-MTX-E12 Co-Culture Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vuppaladadiyam, S.S.V.; Vuppaladadiyam, A.K.; Sahoo, A.; Urgunde, A.; Murugavelh, S.; Šrámek, V.; Pohořelý, M.; Trakal, L.; Bhattacharya, S.; Sarmah, A.K.; et al. Waste to Energy: Trending Key Challenges and Current Technologies in Waste Plastic Management. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a Consensus on the Definition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.K.-H.; Tse, T.W.; Maboloc, E.A.; Leung, R.K.-L.; Leung, M.M.-L.; Wong, M.W.-T.; Chui, A.P.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Kwan, K.Y.; et al. Adverse Impacts of High-Density Microplastics on Juvenile Growth and Behaviour of the Endangered Tri-Spine Horseshoe Crab Tachypleus tridentatus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 187, 114535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Teng, J.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Shan, E.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q. Potential Threats of Microplastics and Pathogenic Bacteria to the Immune System of the Mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 272, 106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Sepúlveda, M.S.; Bi, B.; Huang, Y.; Kong, L.; Yan, H.; Gao, Y. Acute Polyethylene Microplastic (PE-MPs) Exposure Activates the Intestinal Mucosal Immune Network Pathway in Adult Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2023, 311, 137048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, L.; Zhang, H.-T.; Li, J.; Ye, Y.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Zheng, J.-L.; Yan, X. Transgenerational Effects of Microplastics on Nrf2 Signaling, GH/IGF, and HPI Axis in Marine Medaka Oryzias melastigma under Different Salinities. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocker, R.; Silva, E.K. Microplastics in Our Diet: A Growing Concern for Human Health. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 968, 178882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, B.; Dong, R. Detection of Various Microplastics in Placentas, Meconium, Infant Feces, Breastmilk and Infant Formula: A Pilot Prospective Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihart, A.J.; Garcia, M.A.; El Hayek, E.; Liu, R.; Olewine, M.; Kingston, J.D.; Castillo, E.F.; Gullapalli, R.R.; Howard, T.; Bleske, B.; et al. Bioaccumulation of Microplastics in Decedent Human Brains. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winiarska, E.; Jutel, M.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M. The Potential Impact of Nano- and Microplastics on Human Health: Understanding Human Health Risks. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, F.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Microplastics in Human Feces Reveals a Correlation between Fecal Microplastics and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Status. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-W.; Lim, J.Y.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Chiou, J.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Lai, K.P.; Li, L.; Chan, P.K.S.; Fang, J.K.-H. Preliminary Findings of the High Quantity of Microplastics in Faeces of Hong Kong Residents. Toxics 2022, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.G.; Nwankwo, C.E.; Dey, S.; Sundaramurthy, S.; Okeke, E.S. Food Chain Microplastics Contamination and Impact on Human Health: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1889–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Wang, L.; Gu, W.; Li, X.; Han, Z.; Fu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Su, Z. Continuous Oral Exposure to Micro- and Nanoplastics Induced Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, Intestinal Barrier and Immune Dysfunction in Adult Mice. Environ. Int. 2023, 182, 108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woh, P.Y.; Shiu, H.Y.; Fang, J.K.-H. Microplastics in Seafood: Navigating the Silent Health Threat and Intestinal Implications through a One Health Food Safety Lens. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molly, K.; Vande Woestyne, M.; Verstraete, W. Development of a 5-Step Multi-Chamber Reactor as a Simulation of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1993, 39, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, P.; Burmester, M.; Langeheine, M.; Brehm, R.; Empl, M.T.; Seeger, B.; Breves, G. Caco-2/HT29-MTX Co-Cultured Cells as a Model for Studying Physiological Properties and Toxin-Induced Effects on Intestinal Cells. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senathirajah, K.; Attwood, S.; Bhagwat, G.; Carbery, M.; Wilson, S.; Palanisami, T. Estimation of the Mass of Microplastics Ingested—A Pivotal First Step towards Human Health Risk Assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosal, S.; Bag, S.; Rao, S.R.; Bhowmik, S. Exposure to Polyethylene Microplastics Exacerbate Inflammatory Bowel Disease Tightly Associated with Intestinal Gut Microflora. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 25130–25148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Hou, Y.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Farooq, T.H.; Yan, W.; Li, Y. Intestinal Flora Variation Reflects the Short-Term Damage of Microplastic to the Intestinal Tract in Mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, E.; Leveque, M.; Ruiz, P.; Ratel, J.; Durif, C.; Chalancon, S.; Amiard, F.; Edely, M.; Bezirard, V.; Gaultier, E.; et al. Microplastics: What Happens in the Human Digestive Tract? First Evidences in Adults Using in Vitro Gut Models. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, E.; Ratel, J.; Denis, S.; Leveque, M.; Ruiz, P.; Mazal, C.; Amiard, F.; Edely, M.; Bezirard, V.; Gaultier, E.; et al. Exposure to Polyethylene Microplastics Alters Immature Gut Microbiome in an Infant in Vitro Gut Model. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C.; Nagarajan, N.; Gan, Y.-H. Short-Chain Fatty Acids of Various Lengths Differentially Inhibit Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Enterobacteriaceae Species. mSphere 2024, 9, e0078123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, A.; Molinero, N.; Reinosa, J.J.; Alcolea-Rodriguez, V.; Portela, R.; Bañares, M.A.; Fernández, J.F.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. PET Microplastics Affect Human Gut Microbiota Communities during Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion, First Evidence of Plausible Polymer Biodegradation during Human Digestion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wu, Z. Long-Term Exposure to Polystyrene Microspheres and High-Fat Diet–Induced Obesity in Mice: Evaluating a Role for Microbiota Dysbiosis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 097002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Luo, Y.; Song, M.; He, X.; Sheng, H.; Gao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, J.; Cao, C. Polystyrene Microplastics Aggravate Radiation-Induced Intestinal Injury in Mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Arroyo, C.; Tamargo, A.; Molinero, N.; Reinosa, J.J.; Alcolea-Rodriguez, V.; Portela, R.; Bañares, M.A.; Fernández, J.F.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Biodegradable Microplastics and Their Interaction with the Gut Microbiota. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Sung, J.Y.; Yong, D.; Chun, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, J.H.; Chung, K.S.; Kim, E.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Kang, Y.A.; et al. Characterization of Microbiome in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid of Patients with Lung Cancer Comparing with Benign Mass like Lesions. Lung Cancer 2016, 102, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strachan, C.R.; Bowers, C.M.; Kim, B.-C.; Movsesijan, T.; Neubauer, V.; Mueller, A.J.; Yu, X.A.; Pereira, F.C.; Nagl, V.; Faas, J.; et al. Distinct Lactate Utilization Strategies Drive Niche Differentiation between Two Co-Existing Megasphaera Species in the Rumen Microbiome. ISME J. 2025, 19, wraf147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Lau, R.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, M.-H. Lactate Cross-Feeding between Bifidobacterium Species and Megasphaera Indica Contributes to Butyrate Formation in the Human Colonic Environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, M.; Guan, X.; Guo, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, L. Megasphaera elesdenii Dysregulates Colon Epithelial Homeostasis, Aggravates Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e05670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, R.R.; Belt, S.C.; Bakker, B.M.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N. Beyond Butyrate: Microbial Fiber Metabolism Supporting Colonic Epithelial Homeostasis. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinak, N.; Chiewchankaset, P.; Kalapanulak, S.; Panichnumsin, P.; Saithong, T. Metabolic Cross-Feeding Interactions Modulate the Dynamic Community Structure in Microbial Fuel Cell under Variable Organic Loading Wastewaters. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. Interaction between Microplastic Biofilm Formation and Antibiotics: Effect of Microplastic Biofilm and Its Driving Mechanisms on Antibiotic Resistance Gene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Deng, C.; Chen, Y.; Ding, H.; Yu, Z. Do Microplastic Biofilms Promote the Evolution and Co-Selection of Antibiotic and Metal Resistance Genes and Their Associations with Bacterial Communities under Antibiotic and Metal Pressures? J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danopoulos, E.; Twiddy, M.; West, R.; Rotchell, J.M. A Rapid Review and Meta-Regression Analyses of the Toxicological Impacts of Microplastic Exposure in Human Cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 127861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Tian, H.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, F.; Cao, H.; Gao, L.; Liu, M. The Enhancement in Toxic Potency of Oxidized Functionalized Polyethylene-Microplastics in Mice Gut and Caco-2 Cells. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H. Polystyrene Nanoparticles Induced Mammalian Intestine Damage Caused by Blockage of BNIP3/NIX-Mediated Mitophagy and Gut Microbiota Alteration. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 168064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Jiang, Q.; Qin, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, P.; Feng, B.; Liu, X.; Qing, Z.; Qing, T. The Influence of Digestive Tract Protein on Cytotoxicity of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 174023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Thi Quynh Mai, N.; Moon, B.-S.; Choi, J.K. Impact of Polystyrene Microplastics (PS-MPs) on the Entire Female Mouse Reproductive Cycle: Assessing Reproductive Toxicity of Microplastics through in Vitro Follicle Culture. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 297, 118228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.-B.; Kang, H.-M.; Lee, M.-C.; Kim, D.-H.; Han, J.; Hwang, D.-S.; Souissi, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Shin, K.-H.; Park, H.G.; et al. Adverse Effects of Microplastics and Oxidative Stress-Induced MAPK/Nrf2 Pathway-Mediated Defense Mechanisms in the Marine Copepod Paracyclopina Nana. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, X.; Gu, W.; Yu, J.; Wu, B. Influence of the Digestive Process on Intestinal Toxicity of Polystyrene Microplastics as Determined by in Vitro Caco-2 Models. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shruti, V.C.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G. Migration Testing of Microplastics in Plastic Food-Contact Materials: Release, Characterization, Pollution Level, and Influencing Factors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.A.; Prasetya, T.A.E.; Dewi, I.R.; Ahmad, M. Microplastics in Human Food Chains: Food Becoming a Threat to Health Safety. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Besseling, E.; Wegner, A.; Foekema, E.M. Plastic as a Carrier of POPs to Aquatic Organisms: A Model Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7812–7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, L.M.; Jones, P.R.; Moore, C.; Narayan, U.V. Quantitation of Persistent Organic Pollutants Adsorbed on Plastic Debris from the Northern Pacific Gyre’s “Eastern Garbage Patch”. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 2226–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, X.; Su, C.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, J.K.-H.; Woh, P.Y. Microplastic Toxicity on Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Cells: Evidence from the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME). Toxics 2025, 13, 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121045

Ren X, Su C, Zhu Y, Fang JK-H, Woh PY. Microplastic Toxicity on Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Cells: Evidence from the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME). Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121045

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Xingchao, Chen Su, Yuyan Zhu, James Kar-Hei Fang, and Pei Yee Woh. 2025. "Microplastic Toxicity on Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Cells: Evidence from the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME)" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121045

APA StyleRen, X., Su, C., Zhu, Y., Fang, J. K.-H., & Woh, P. Y. (2025). Microplastic Toxicity on Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Cells: Evidence from the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME). Toxics, 13(12), 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121045