Ecotoxicity of Nitrated Monoaromatic Hydrocarbons in Aquatic Systems: Emerging Risks from Atmospheric Deposition of Biomass Burning and Anthropogenic Aerosols

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. BB and AA Aerosols Collection and Leaching

2.3. Quantification of NMAHs in sBB and AA Aerosol Extracts

2.4. Bioassays

2.4.1. Interaction with Phase 0 Membrane Transporters Oct1 and Oatp1d1

2.4.2. Interaction with Phase I Cellular Detoxification: The EROD Test

2.4.3. Acute Cytotoxicity: The MTT Assay

2.4.4. Chronic Toxicity: The AlgaeTox Assay

2.4.5. Zebrafish Maintenance and Embryotoxicity Assay

2.5. Extraction and Detection of Lipids in Zebrafish Embryos Exposed to NMAHs

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Aerosol Extracts

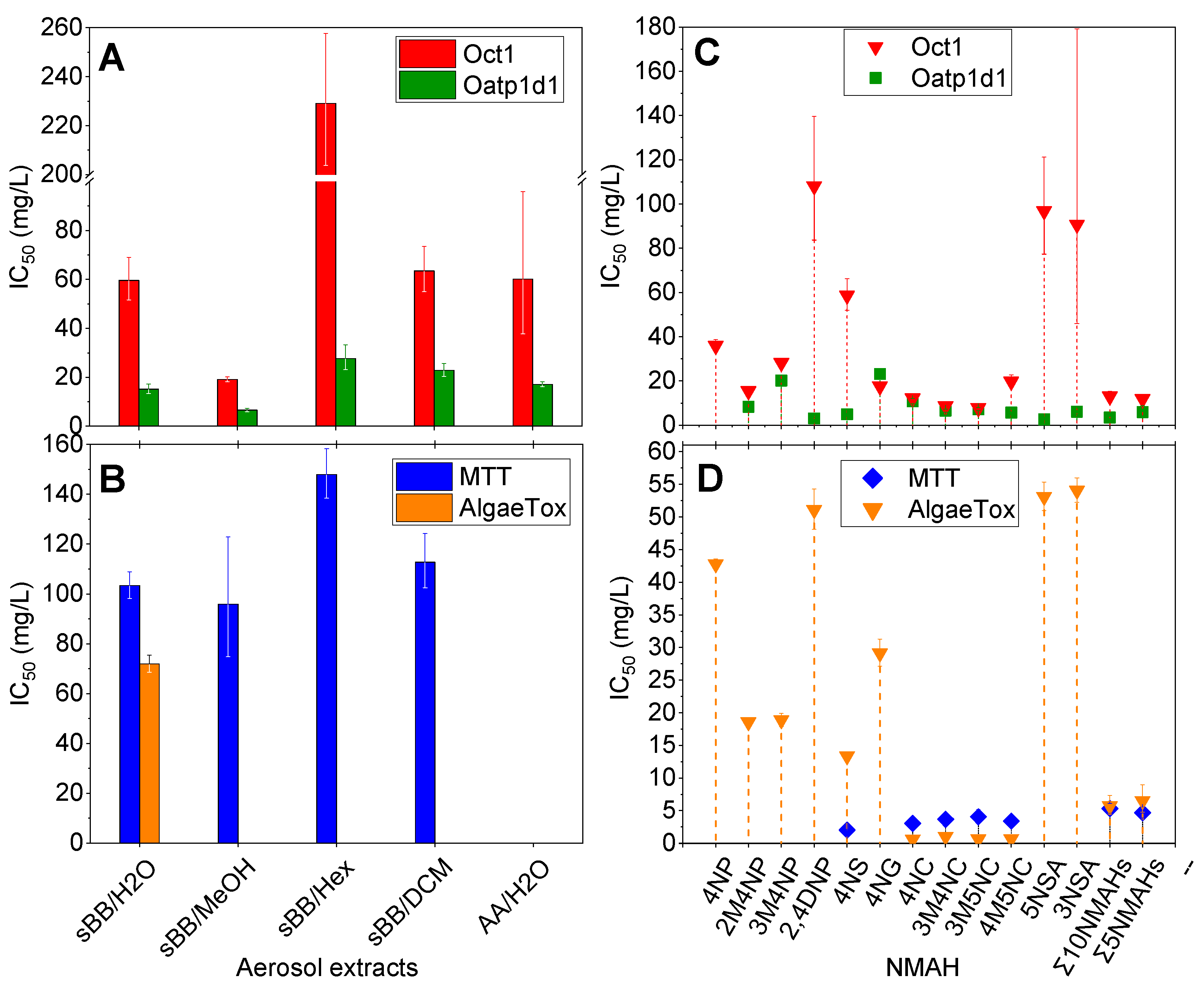

3.1.1. Effects of Aerosol Extracts on Phase 0 and I of Cellular Detoxification

3.1.2. Acute and Chronic Effects of Aerosol Extracts

3.2. Individual NMAHs

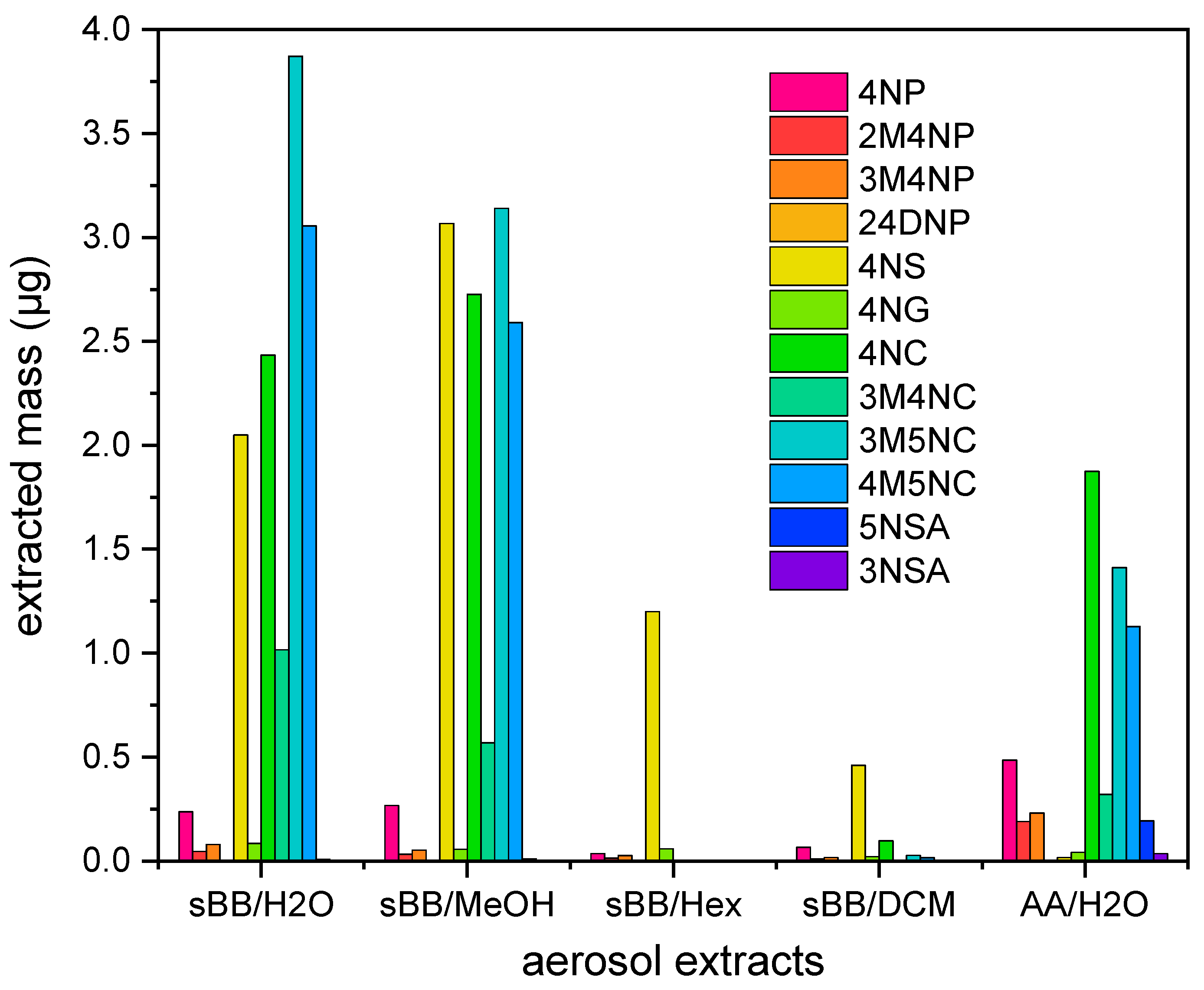

3.2.1. Concentration of NMAHs in Aerosols Extracts

3.2.2. Effects of NMAHs on Phase 0 and I of Cellular Detoxification

3.2.3. Acute and Chronic Effects of NMAHs

3.2.4. NMAHs Toxicity to Zebrafish Embryos

3.2.5. NMAHs Exposure Altered Lipids of Zebrafish Embryos

4. Discussion

4.1. NMAHs Contributed to Ecotoxicity of Atmospheric Aerosols

4.2. Interaction of NMAHs with Oct1 and Oatp1d1 Membrane Transporters

4.3. Role of Aerosols and NMAHs in Phase I of Cellular Detoxification

4.4. NMAHs Impacted Lipid Homeostasis of Zebrafish Embryos

4.5. Ecological Impact of NMAHs Under Climate Changes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,2DG | 1,2-Diacylglycerols |

| 1,3DG | 1,3-Diacylglycerols |

| AA | Ambient anthropogenic |

| AAH2O | Extract of AA aerosols in water |

| ALC | Alcohols |

| ASP+ | 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide |

| BB | Biomass burning |

| COH | Cholesterol |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DGDG | Digalactosyldiacylglycerols |

| EC50 | Half-maximal effect concentration of xenobiotic |

| FFA | Free Fatty Acids |

| GL | Glycolipids |

| GUA | Guaiacol |

| Hex | Hexane |

| LC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry |

| LY | Lucifer yellow |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| MGDG | Monogalactosyldiacylglycerols |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide |

| NC | Nitrocatechol |

| NG | nitroguaiacol |

| NMAH | Nitrated monoaromatic hydrocarbons |

| NP | Nitrophenol |

| NS | Nitrosyringol |

| NSA | Nitrosalicylic acid |

| Oatp1d1 | Organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1d1 |

| Oct1 | Organic cation transporter 1 |

| PAHs | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PG | Phosphatidylglycerol |

| PL | Phospholipids |

| sBB | Simulated biomass burning |

| sBBDCM | Extract of sBB aerosols in dichloromethane |

| sBBH2O | Extract of sBB aerosols in water |

| sBBHex | Extract of sBB aerosols in hexane |

| sBBMeOH | Extract of sBB aerosols in methanol |

| SQDG | Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerols |

| TG | Triacylglycerols |

| TPSA | Topological polar surface area |

| WE | Wax esters |

References

- Poschl, U. Atmospheric aerosols: Composition, transformation, climate and health effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit 2005, 44, 7520–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turóczi, B.; Hoffer, A.; Tóth, A.; Kováts, N.; Acs, A.; Ferincz, A.; Kovács, A.; Gelencsér, A. Comparative assessment of ecotoxicity of urban aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 7365–7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, C.M.; Constantin, D.E.; Voiculescu, M.; Georgescu, L.P.; Merlaud, A.; Van Roozendael, M. Modeling results of atmospheric dispersion of NO in an urban area using METI-LIS and comparison with coincident mobile DOAS measurements. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2015, 6, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, M.O. Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning—An updated assessment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 8523–8546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besis, A.; Tsolakidou, A.; Balla, D.; Samara, C.; Voutsa, D.; Pantazaki, A.; Choli-Papadopoulou, T.; Lialiaris, T.S. Toxic organic substances and marker compounds in size-segregated urban particulate matter—Implications for involvement in the in vitro bioactivity of the extractable organic matter. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 230, 758–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Xing, R.; Luo, Z.H.; Huang, W.X.; Yi, F.; Men, Y.; Zhao, N.; Chang, Z.F.; Zhao, J.F.; Pan, B.; et al. Pollutant emissions from biomass burning: A review on emission characteristics, environmental impacts, and research perspectives. Particuology 2024, 85, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iinuma, Y.; Boge, O.; Grafe, R.; Herrmann, H. Methyl-Nitrocatechols: Atmospheric Tracer Compounds for Biomass Burning Secondary Organic Aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8453–8459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claeys, M.; Vermeylen, R.; Yasmeen, F.; Gomez-Gonzalez, Y.; Chi, X.G.; Maenhaut, W.; Meszaros, T.; Salma, I. Chemical characterisation of humic-like substances from urban, rural and tropical biomass burning environments using liquid chromatography with UV/vis photodiode array detection and electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. Environ. Chem. 2012, 9, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frka, S.; Šala, M.; Brodnik, H.; Stefane, B.; Kroflič, A.; Grgić, I. Seasonal variability of nitroaromatic compounds in ambient aerosols: Mass size distribution, possible sources and contribution to water-soluble brown carbon light absorption. Chemosphere 2022, 299, 134381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljević, I.; Šimić, I.; Mendas, G.; Štrukil, Z.S.; Žužul, S.; Gluščić, V.; Godec, R.; Pehnec, G.; Bešlić, I.; Milinković, A.; et al. Pollution levels and deposition processes of airborne organic pollutants over the central Adriatic area: Temporal variabilities and source identification. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 172, 112873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitanovski, Z.; Hovorka, J.; Kuta, J.; Leoni, C.; Prokes, R.; Sanka, O.; Shahpoury, P.; Lammel, G. Nitrated monoaromatic hydrocarbons (nitrophenols, nitrocatechols, nitrosalicylic acids) in ambient air: Levels, mass size distributions and inhalation bioaccessibility. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 59131–59140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, K.S.; Huang, X.H.H.; Yu, Y.Z. Quantification of nitroaromatic compounds in atmospheric fine particulate matter in Hong Kong over 3 years: Field measurement evidence for secondary formation derived from biomass burning missions. Environ. Chem. 2015, 13, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.R.; Wang, X.F.; Li, M.; Liang, Y.H.; Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, J.; Guan, T.Y.; Mu, J.S.; Zhu, Y.J.; Meng, H.; et al. Comprehensive understanding on sources of high levels of fine particulate nitro-aromatic compounds at a coastal rural area in northern China. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 135, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, A.; Pellegrino, V.; Gamberini, R.; Calabria, A. An evidence for nitrophenols contamination in Antarctic fresh-water and snow. Simultaneous determination of nitrophenols and nitroarenes at ng/L levels. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2001, 79, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Li, J.; Wang, G.H.; Zhang, T.; Dai, W.T.; Ho, K.F.; Wang, Q.Y.; Shao, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, L. Molecular characteristics of organic compositions in fresh and aged biomass burning aerosols. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finewax, Z.; de Gouw, J.A.; Ziemann, P.J. Identification and Quantification of 4-Nitrocatechol Formed from OH and NO3 Radical-Initiated Reactions of Catechol in Air in the Presence of NOx: Implications for Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation from Biomass Burning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.A.J.; Barra, S.; Borghesi, D.; Vione, D.; Arsene, C.; Olariu, R.L. Nitrated phenols in the atmosphere: A review. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.L.; Moreira, V.R.; Lebron, Y.A.R.; Santos, A.V.; Santos, L.V.S.; Amaral, M.C.S. Phenolic compounds seasonal occurrence and risk assessment in surface and treated waters in Minas Gerais-Brazil. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calza, P.; Massolino, C.; Pelizzetti, E.; Mineto, C. Solar driven production of toxic halogenated and nitroaromatic compounds in natural seawater. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 398, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflieger, M.; Kroflič, A. Acute toxicity of emerging atmospheric pollutants from wood lignin due to biomass burning. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 338, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylan, Z.; Sisman, T.; Yazici, Z.; Altikat, A.O. Embryotoxicity of nitrophenols to the early life stages of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol. Ind. Health 2016, 32, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalecz-Jawecki, G.; Sawicki, J. Influence of pH on the toxicity of nitrophenols to Microtox (R) and Spirotox tests. Chemosphere 2003, 52, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babić, S.; Čizmek, L.; Maršavelski, A.; Malev, O.; Pflieger, M.; Strunjak-Perović, I.; Popović, N.T.; Čoz-Rakovac, R.; Trebše, P. Utilization of the zebrafish model to unravel the harmful effects of biomass burning during Amazonian wildfires. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S.EPA. Toxic and Priority Pollutants Under the Clean Water Act. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/eg/toxic-and-priority-pollutants-under-clean-water-act (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- U.S.EPA. List of Hazardous Air Pollutants Under the Clean Air Act. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/haps/initial-list-hazardous-air-pollutants-modifications (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Wang, X.F.; Gu, R.R.; Wang, L.W.; Xu, W.X.; Zhang, Y.T.; Chen, B.; Li, W.J.; Xue, L.K.; Chen, J.M.; Wang, W.X. Emissions of fine particulate nitrated phenols from the burning of five common types of biomass. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 230, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frka, S.; Šala, M.; Kroflič, A.; Huš, M.; Čusak, A.; Grgić, I. Quantum Chemical Calculations Resolved Identification of Methylnitrocatechols in Atmospheric Aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5526–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanovski, Z.; Grgić, I.; Vermeylen, R.; Claeys, M.; Maenhaut, W. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for characterization of monoaromatic nitro-compounds in atmospheric particulate matter. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1268, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanovski, Z.; Grgic, I.; Yasmeen, F.; Claeys, M.; Cusak, A. Development of a liquid chromatographic method based on ultraviolet-visible and electrospray ionization mass spectrometric detection for the identification of nitrocatechols and related tracers in biomass burning atmospheric organic aerosol. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 26, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljević, I.; Popović, M.; Žaja, R.; Maraković, N.; Sinko, G.; Smital, T. Interaction between the zebrafish (Danio rerio) organic cation transporter 1 (Oct1) and endo-and xenobiotics. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 187, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, P.; Ahel, M.; Maraković, N.; Lončar, J.; Mihaljević, I.; Smital, T. Selective interaction of microcystin congeners with zebrafish (Danio rerio) Oatp1d1 transporter. Chemosphere 2021, 283, 131155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.E.; Woodward, B.L.; Stegeman, J.J.; Kennedy, S.W. Rapid assessment of induced cytochrome P4501A protein and catalytic activity in fish hepatoma cells grown in multiwell plates: Response to TCDD, TCDF, and two planar PCBS. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1996, 15, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzen, A.; Kennedy, S.W. A Fluorescence-Based Protein Assay for Use with a Microplate Reader. Anal. Biochem. 1993, 214, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival—Application to Proliferation and Cyto-Toxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmel, C.B.; Ballard, W.W.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ullmann, B.; Schilling, T.F. Stages of Embryonic-Development of the Zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 1995, 203, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 236: Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A Rapid Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can. J. Biochem. Phys. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyares, R.L.; de Rezende, V.B.; Farber, S.A. Zebrafish yolk lipid processing: A tractable tool for the study of vertebrate lipid transport and metabolism. Dis. Model. Mech. 2014, 7, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gašparović, B.; Kazazić, S.P.; Cvitešić, A.; Penezić, A.; Frka, S. Improved separation and analysis of glycolipids by Iatroscan thin-layer chromatography-flame ionization detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1409, 259–267, Erratum in J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1521, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachicho, N.; Reithel, S.; Miltner, A.; Heipieper, H.J.; Küster, E.; Luckenbach, T. Body Mass Parameters, Lipid Profiles and Protein Contents of Zebrafish Embryos and Effects of 2,4-Dinitrophenol Exposure. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraher, D.; Sanigorski, A.; Mellett, N.A.; Meikle, P.J.; Sinclair, A.J.; Gibert, Y. Zebrafish Embryonic Lipidomic Analysis Reveals that the Yolk Cell Is Metabolically Active in Processing Lipid. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGruer, V.; Bhatia, A.; Magnuson, J.T.; Schlenk, D. Lipid Profile Altered in Phenanthrene Exposed Zebrafish Embryos with Implications for Neurological Development and Early Life Nutritional Status. Environ. Health 2023, 1, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, S.; Doerksen, R.J. Topological Polar Surface Area: A Useful Descriptor in 2D-QSAR. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbach, R.P.; Stierli, R.; Folsom, B.R.; Zeyer, J. Compound Properties Relevant for Assessing the Environmental Partitioning of Nitrophenols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1988, 22, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, R.A.; Biggs, A.I. The Thermodynamic Ionization Constant of Para-Nitrophenol from Spectrophotometric Measurements. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1955, 51, 901–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.A. Dissociation Constants of Some Substituted Nittropenols in Aqueous Solution at 25 °C. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. Sect. A Phys. Chem. 1967, 71A, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, R.; Ozer, U.; Turkel, N. Potentiometric and spectroscopic determination of acid dissociation constants of some phenols and salicylic acids. Turk. J. Chem. 1997, 21, 428–436. [Google Scholar]

- Kitanovski, Z.; Shahpoury, P.; Samara, C.; Voliotis, A.; Lammel, G. Composition and mass size distribution of nitrated and oxygenated aromatic compounds in ambient particulate matter from southern and central Europe—Implications for the origin. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 2471–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, C.; Delgado, L.S.; Barrett, D.; Simonich, S.L.M.; Tanguay, R.L. PM2.5 Filter Extraction Methods: Implications for Chemical and Toxicological Analyses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hund, K. Algal growth inhibition test—Feasibility and limitations for soil assessment. Chemosphere 1997, 35, 1069–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, M.; Žaja, R.; Fent, K.; Smital, T. Interaction of environmental contaminants with zebrafish organic anion transporting polypeptide, Oatp1d1 (Slco1d1). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 280, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Rohde, B.; Selzer, P. Fast calculation of molecular polar surface area as a sum of fragment-based contributions and its application to the prediction of drug transport properties. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3714–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popović, M.; Žaja, R.; Fent, K.; Smital, T. Molecular Characterization of Zebrafish Oatp1d1 (Slco1d1), a Novel Organic Anion-transporting Polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 33894–33911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosveld, A.T.C.; de Bie, P.A.F.; van den Brink, N.W.; Jongepier, H.; Klomp, A.V. In vitro EROD induction equivalency factors for the 10 PAHs generally monitored in risk assessment studies in The Netherlands. Chemosphere 2002, 49, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiard, S.M.; Bols, N.C.; Hodson, P.V. In vitro and in vivo comparisons of fish-specific CYP1A induction relative potency factors for selected polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2004, 59, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Al-Attas, O.S.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Mohammed, A.A.; De Rosas, E.; Ibrahim, S.; Vinodson, B.; Ansari, M.G.; El-Din, K.I.A. Induction of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1, increased oxidative stress and inflammation in the lung and liver tissues of rats exposed to incense smoke. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2014, 391, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanger, S.E.; Rawlings, J.M.; Carr, G.J. Use of fish embryo toxicity tests for the prediction of acute fish toxicity to chemicals. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 1768–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marit, J.S.; Weber, L.P. Acute exposure to 2,4-dinitrophenol alters zebrafish swimming performance and whole body triglyceride levels. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C 2011, 154, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, M.; Kavčić, A.; Debeljak, M.; Šala, M.; Grdadolnik, J.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Kroflič, A. Toxicity of nitrophenolic pollutant 4-nitroguaiacol to terrestrial plants and comparison with its non-nitro analogue guaiacol (2-methoxyphenol). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.D.; Ferreira, P.L.; Pedersen, J.S.T. The Climate Change Challenge: A Review of the Barriers and Solutions to Deliver a Paris Solution. Climate 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, R.; Osborn, T.J.; Kushnir, Y.; Simpson, I.R.; Nakamura, J.; Liu, H.B. Climate Variability and Change of Mediterranean-Type Climates. J. Climate 2019, 32, 2887–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberer, T.; Schmidt-Baumler, K.; Stan, H.J. Occurrence and distribution of organic contaminants in the aquatic system in Berlin. Part 1: Drug residues and other polar contaminants in Berlin surface and groundwater. Acta Hydrochim. Hydrobiol. 1998, 26, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennrich, L.; Efer, J.; Engewald, W. Gas-Chromatographic Trace Analysis of Underivatized Nitrophenols. Chromatographia 1995, 41, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, H.; Tai, A.P.K.; Martin, M.V.; Yung, D.H.Y. Responses of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air quality to future climate, land use, and emission changes: Insights from modeling across shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeseler, G.; Piepenbrink, A.; Bufler, J.; Dengler, R.; Aronson, J.K.; Piepenbrock, S.; Leuwer, M. Structural requirements for voltage-dependent block of muscle sodium channels by phenol derivatives. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 132, 1916–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inokuchi, H.; McLachlan, E.M.; Meckler, R.L. The effects of catechol on various membrane conductances in lumbar sympathetic postganglionic neurones of the guinea-pig. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1997, 355, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.J.; Song, J.P.; Dong, C.; Choi, M.M.F. Fluorescence quenching method for the determination of catechol with gold nanoparticles and tyrosinase hybrid system. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2010, 21, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljević, I.; Sever Štrukil, Z.; Pehnec, G.; Bešlić, I.; Milinković, A.; Bakija Alempijević, S.; Frka, S. Comparison of PAH Mass Concentrations in Aerosols of the Middle Adriatic Coast Area and Central Croatia. Kem. Ind. 2020, 69, P75–P82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NMAH | Structure | MW | log Kow a | TPSA b /Å2 | pK1 | pK2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-nitrophenol (4NP) |  | 139.11 | 1.91 | 66 | 7.1 c | / |

| 2-methyl-4-nitrophenol (2M4NP) |  | 153.14 | 2.46 | 66 | nd | / |

| 3-methyl-4-nitrophenol (3M4NP) |  | 153.14 | 2.46 | 66 | 7.33 d | / |

| 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4DNP) |  | 184.11 | 1.7 | 112 | 4.1 e | / |

| 4-nitrosyringol (4NS) |  | 199.16 | nd | 84.5 | nd | / |

| 4-nitroguaiacol (4NG) |  | 169.13 | 1.73 | 75.3 | nd | / |

| 4-nitrocatechol (4NC) |  | 155.11 | 1.66 | 86.3 | 6.6 f | 10.8 f |

| 3-methyl-4-nitrocatechol (3M4NC) |  | 169.13 | nd | 86.3 | nd | nd |

| 3-methyl-5-nitrocatechol (3M5NC) |  | 169.13 | 2.14 | 86.3 | nd | nd |

| 4-methyl-5-nitrocatechol (4M5NC) |  | 169.13 | 1.98 | 86.3 | nd | nd |

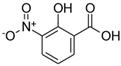

| 5-nitrosalicylic acid (5NSA) |  | 183.12 | 2.64 | 103 | 8.9 f | 10.9 f |

| 3-nitrosalicylic acid (3NSA) |  | 183.12 | 2.64 | 103 | nd | nd |

| NMAH | Concentration (mg/L) | Observed Effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | ||

| 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4DNP) | 4.6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 9.2 * | ✓ | Delayed development | Delayed development | |

| 13.8 | Weak or no pigmentation | Irregular yolk shape Heart edema | Irregular yolk shape | |

| 18.4 | Weak or no pigmentation | Spine malformations | Spine and lethal malformations | |

| 4-nitrocatechol (4NC) | 7.8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15.5 | ✓ | Delayed development | ✓ | |

| 38.8 * | Head malformations Tail necrosis Weak or no pigmentation | Delayed development | ✓ | |

| 77.6 | ✓ | Delayed development Tail necrosis Weak or no pigmentation | Spine malformations | |

| 93.1 | Heart edema Tail necrosis Weak or no pigmentation | Spine malformations | Necrosis | |

| 139.6 | Head and tail necrosis | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

| 186.1 | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

| 3-methyl-5nitrocatechols (3M5NC) | 8.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 16.9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 42.3 * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 50.7 | Head and tail necrosis Irregular yolk shape | Delayed development Necrosis | Lethal malformations | |

| 67.7 | Head and tail necrosis | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

| 84.6 | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

| 101.5 | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

| 152.2 | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | ||

| 4-nitroguaiacol (4NG) | 8.5 | ✓ | Delayed development | ✓ |

| 16.9 | ✓ | Delayed development | ✓ | |

| 42.3 * | Weak or no pigmentation | Delayed development | ✓ | |

| 84.6 | Head and tail necrosis Lethal malformations | Delayed development | ✓ | |

| 101.5 | Necrosis | Delayed development | Delayed development Heart edema | |

| 152.2 | Necrosis | Delayed development Heart edema | Heart edema Spine malformations | |

| 203.0 | Lethal malformations | Delayed development Heart edema | Malformations | |

| 4-nitrosyringol (4NS) | 5.0 * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 6.0 | ✓ | ✓ | Heart edema | |

| 10.0 | ✓ | ✓ | Heart edema | |

| 12.0 | Necrosis | Heart edema | Necrosis Spine malformations | |

| 14.9 | Necrosis | Heart edema | Necrosis Spine malformations | |

| 29.9 | Lethal Malformations | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

| 44.8 | Lethal Malformations | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

| 59.8 | Lethal Malformations | Lethal malformations | Lethal malformations | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakija Alempijević, S.; Strmečki, S.; Mihaljević, I.; Frka, S.; Dragojević, J.; Jakovljević, I.; Smital, T. Ecotoxicity of Nitrated Monoaromatic Hydrocarbons in Aquatic Systems: Emerging Risks from Atmospheric Deposition of Biomass Burning and Anthropogenic Aerosols. Toxics 2025, 13, 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121037

Bakija Alempijević S, Strmečki S, Mihaljević I, Frka S, Dragojević J, Jakovljević I, Smital T. Ecotoxicity of Nitrated Monoaromatic Hydrocarbons in Aquatic Systems: Emerging Risks from Atmospheric Deposition of Biomass Burning and Anthropogenic Aerosols. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121037

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakija Alempijević, Saranda, Slađana Strmečki, Ivan Mihaljević, Sanja Frka, Jelena Dragojević, Ivana Jakovljević, and Tvrtko Smital. 2025. "Ecotoxicity of Nitrated Monoaromatic Hydrocarbons in Aquatic Systems: Emerging Risks from Atmospheric Deposition of Biomass Burning and Anthropogenic Aerosols" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121037

APA StyleBakija Alempijević, S., Strmečki, S., Mihaljević, I., Frka, S., Dragojević, J., Jakovljević, I., & Smital, T. (2025). Ecotoxicity of Nitrated Monoaromatic Hydrocarbons in Aquatic Systems: Emerging Risks from Atmospheric Deposition of Biomass Burning and Anthropogenic Aerosols. Toxics, 13(12), 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121037