Dimethyl Sulfoxide as a Biocompatible Extractant for Enzymatic Bioluminescent Toxicity Assays: Experimental Validation and Molecular Dynamics Insights

Highlights

- DMSO effectively extracts diesel hydrocarbons from contaminated soils while preserving the activity of the BLuc–Red bioluminescent enzyme system.

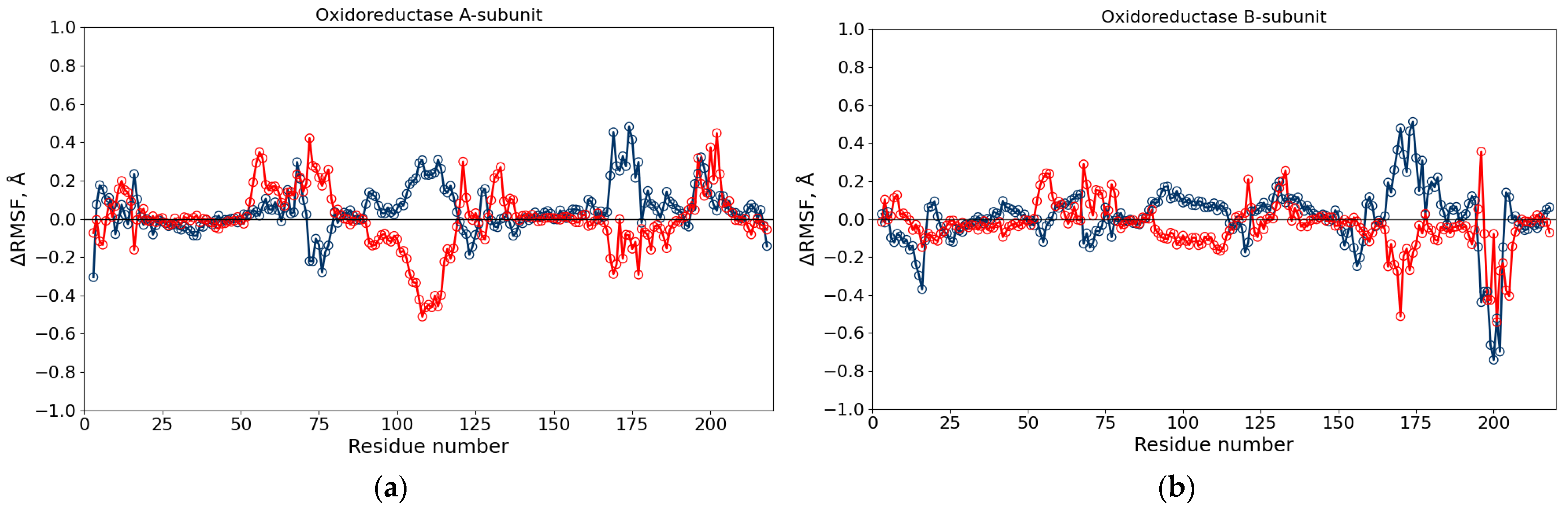

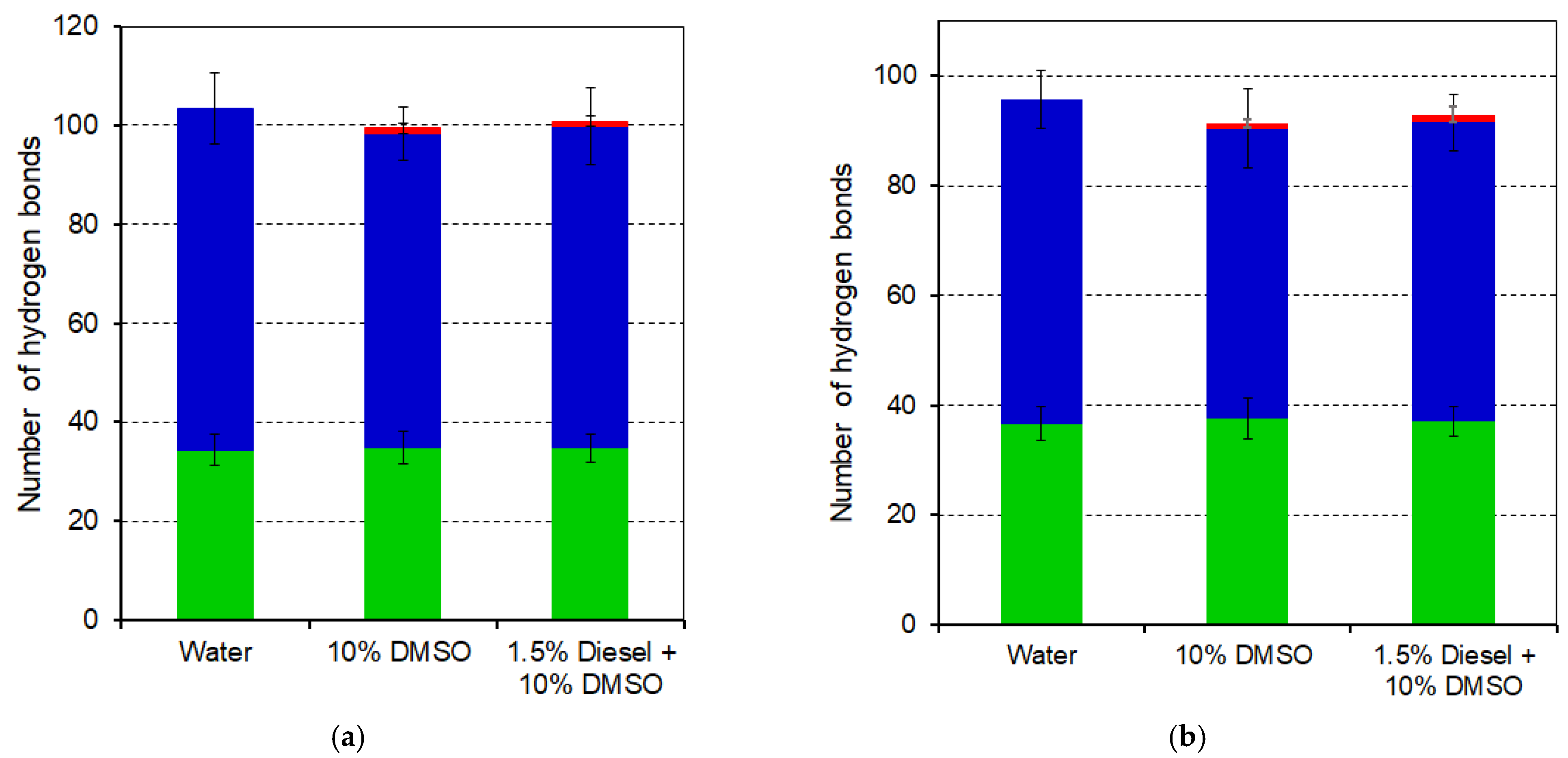

- Molecular dynamics simulations showed that DMSO induces only local flexibility changes in the enzymes, without structural destabilization.

- The study demonstrates that DMSO is a suitable medium for integrating chemical extraction with bioassay-based toxicity assessment.

- The approach can improve the reliability of ecotoxicological monitoring of petroleum-contaminated soils.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling and Characterization

2.2. Preparation of Diesel-Contaminated Samples

2.3. Bioluminescent Enzymatic Assay

2.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the BLuc–Red System

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

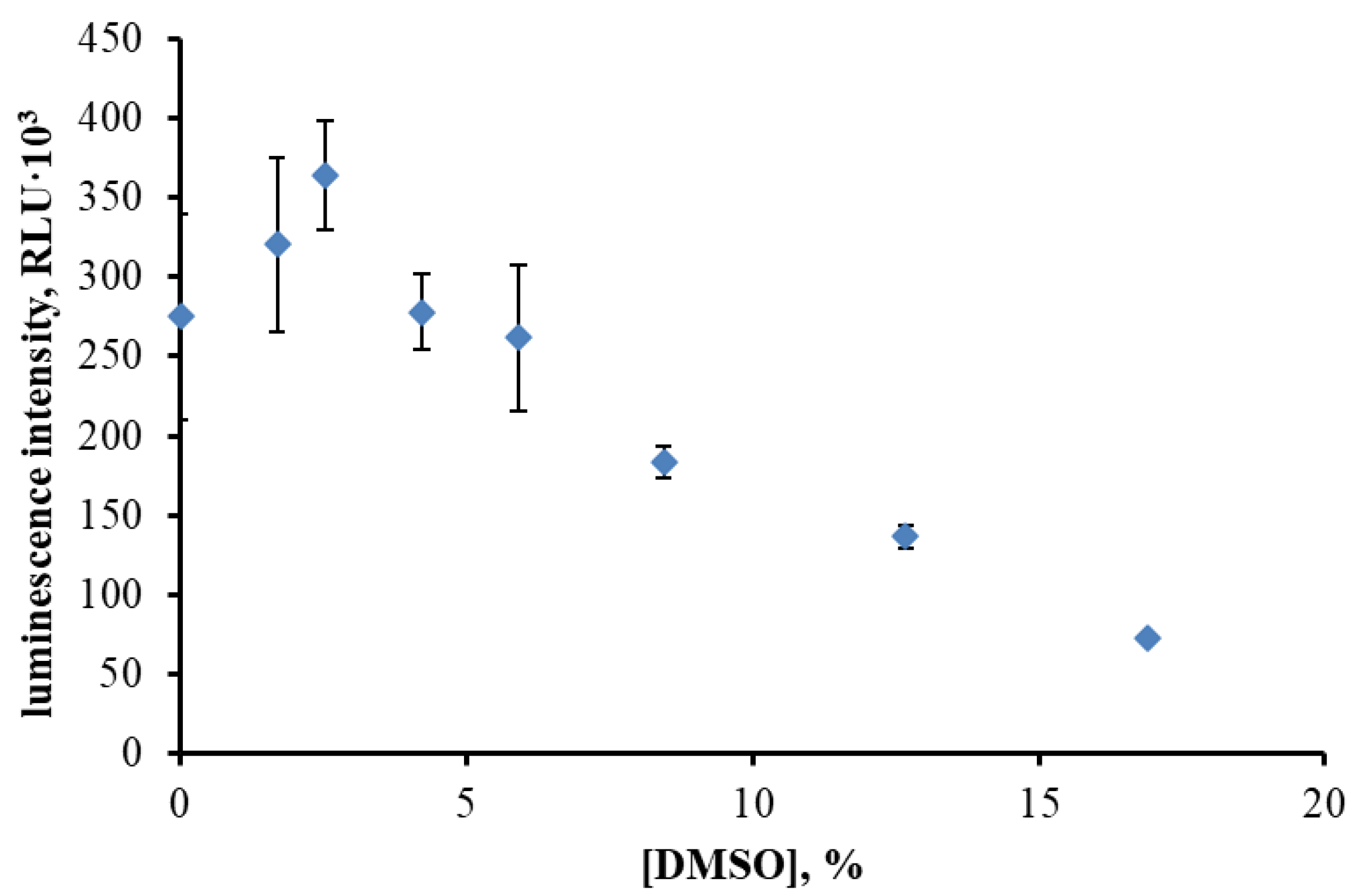

3.1. Effect of DMSO Concentration on BLuc–Red Enzymatic Activity

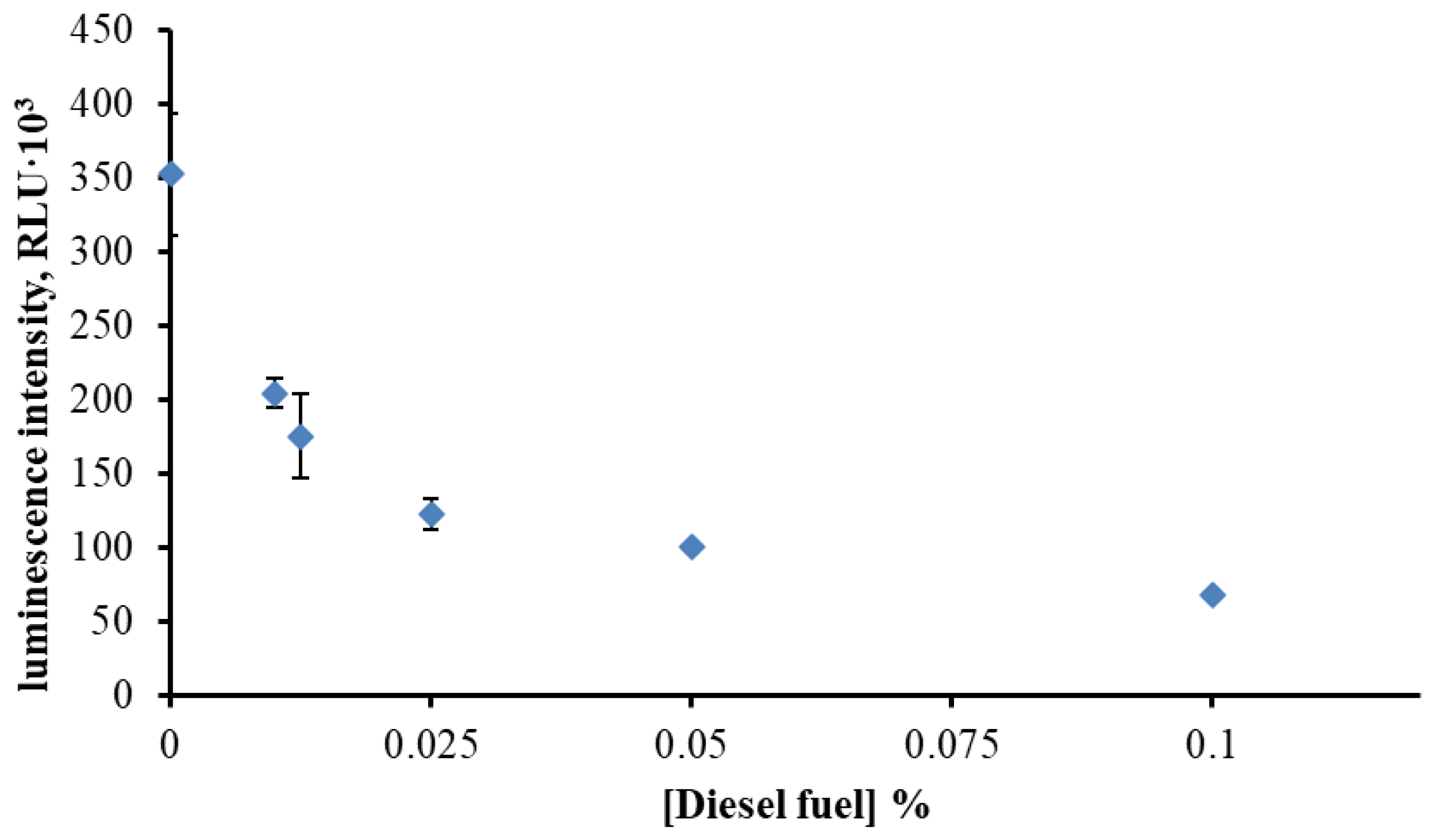

3.2. Effect of Diesel Fuel Dissolved in DMSO

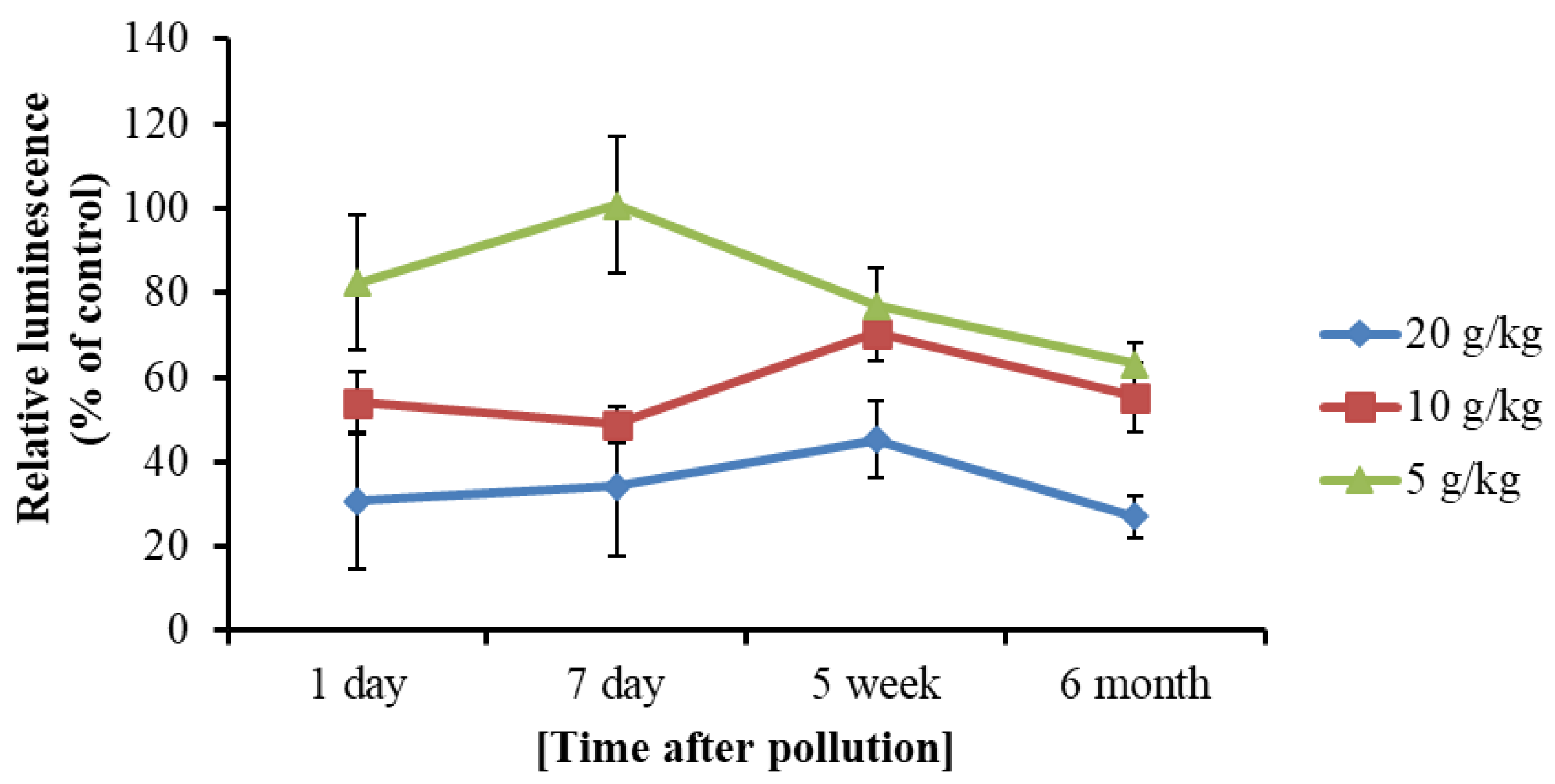

3.3. Toxicity of Soil Extracts from Contaminated Samples

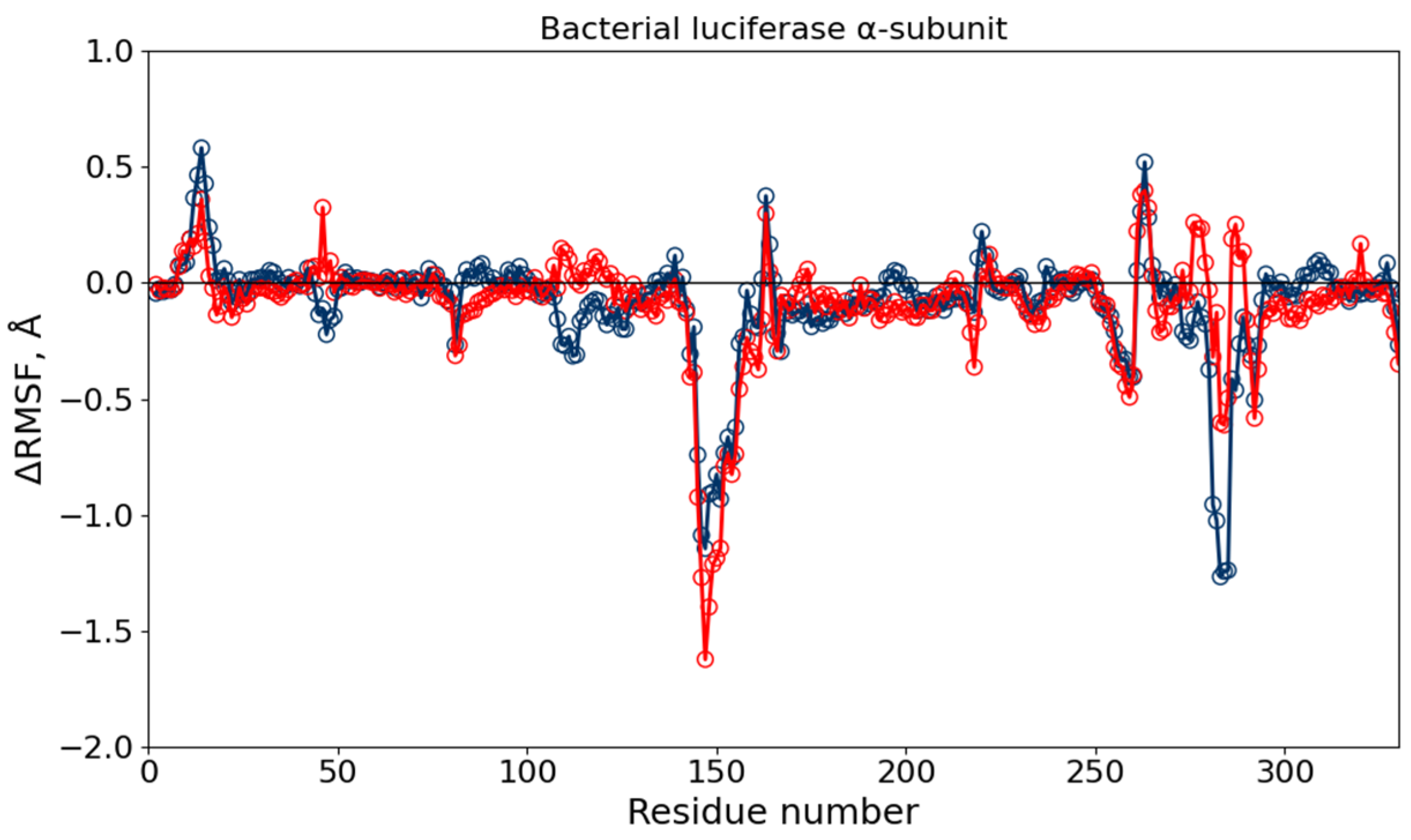

3.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Luciferase and Reductase

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BLuc–Red | Coupled bioluminescent enzymatic system consisting of NAD(P)H:FMN-oxidoreductase and bacterial luciferase |

| C14 | Myristic aldehyde (tetradecanal), substrate for bacterial luciferase |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| FMN | Flavin mononucleotide |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| NPT | Constant pressure and temperature ensemble (isothermal–isobaric ensemble) |

| NVT | Constant volume and temperature ensemble (canonical ensemble) |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | Root mean square fluctuation |

| Rg | Radius of gyration |

| SASA | Solvent-accessible surface area |

| TPH | Total petroleum hydrocarbons |

References

- Alipour, M. Petroleum Accumulation and Preservation. In Basics of Petroleum Geochemistry: With Examples from the Zagros Fold and Thrust Belt of Iran; Alipour, M., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 47–54. ISBN 9783031869389. [Google Scholar]

- Emenike, E.C.; Adeleke, J.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Ogunniyi, S.; Adeyanju, C.A.; Amusa, V.T.; Okoro, H.K.; Adeniyi, A.G. Adsorption of Crude Oil from Aqueous Solution: A Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 50, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Alves, M.K.; Mariz, C.F.; dos Santos, S.M.V.; Nascimento, J.V.G.; Melo, T.J.B.d.; Maia, N.V.d.S.; Alves, R.N.; Zanardi-Lamardo, E.; Feitosa, J.L.L.; Adam, M.L.; et al. Chronic Toxicity after the Oil Spill on the Brazilian Coast Based on Ecotoxicological Biomarkers in the Reef Fish Stegastes Fuscus (Cuvier, 1830). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 220, 118487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshlaf, E.; Ball, A.S. Soil Bioremediation Approaches for Petroleum Hydrocarbon Polluted Environments. AIMS Microbiol 2017, 3, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeloh, H.; Hakvåg, S.; Bakke, I.; Øverjordet, I.B.; Ribičić, D.; Brakstad, O.G. Depletion of Crude Oil and Fuel in the Arctic. Summer and Winter Field Studies with Immobilized Oil in Seawater at Svalbard. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 971, 179043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulon, F.; Pelletier, E.; Gourhant, L.; Delille, D. Effects of Nutrient and Temperature on Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Contaminated Sub-Antarctic Soil. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, M.; Avila-Forcada, A.P.; Gutierrez-Ruiz, M.E. An Improved Gravimetric Method to Determine Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Contaminated Soils. Water Air Soil Pollut 2008, 194, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16703:2004; Soil Quality — Determination of Content of Hydrocarbon in the Range C10 to C40 by Gas Chromatography. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/39937.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Daâssi, D.; Qabil Almaghribi, F. Petroleum-Contaminated Soil: Environmental Occurrence and Remediation Strategies. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eickhoff, C. Testing Difficult Substances for Aquatic Toxicity: Strategies for Poorly Water Soluble Test Items. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2014, 10, 476–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufli, H.; Fisk, P.R.; Girling, A.E.; King, J.M.H.; Länge, R.; Lejeune, X.; Stelter, N.; Stevens, C.; Suteau, P.; Tapp, J.; et al. Aquatic Toxicity Testing of Sparingly Soluble, Volatile, and Unstable Substances and Interpretation and Use of Data. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1998, 39, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Rodríguez, M.D.; García Gómez, M.C.; Alonso Blazquez, N.; Tarazona, J.V. Soil Pollution Remediation. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 344–355. ISBN 9780123864550. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.H.A.; Van Ginkel, S.W.; Hussein, M.A.M.; Abskharon, R.; Oh, S.-E. Toxicity Assessment Using Different Bioassays and Microbial Biosensors. Environ. Int. 2016, 92–93, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esimbekova, E.N.; Kalyabina, V.P.; Kopylova, K.V.; Torgashina, I.G.; Kratasyuk, V.A. Design of Bioluminescent Biosensors for Assessing Contamination of Complex Matrices. Talanta 2021, 233, 122509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimashevskaya, A.A.; Muchkina, E.Y.; Sutormin, O.S.; Chuyashenko, D.E.; Gareev, A.R.; Tikhnenko, S.A.; Rimatskaya, N.V.; Kratasyuk, V.A. Bioluminescence Inhibition Bioassay for Estimation of Snow Cover in Urbanised Areas within Boreal Forests of Krasnoyarsk City. Forests 2024, 15, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.W.; Herschler, R. Pharmacology of DMSO. Cryobiology 1986, 23, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, W.; Melvin, S.D.; Leusch, F.D.L.; Luengen, A.; MacFarlane, G.R. A Metabolomic Analysis on the Toxicological Effects of the Universal Solvent, Dimethyl Sulfoxide. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 2025, 287, 110073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modrzyński, J.J.; Christensen, J.H.; Brandt, K.K. Evaluation of Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) as a Co-Solvent for Toxicity Testing of Hydrophobic Organic Compounds. Ecotoxicology 2019, 28, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Tam, B.; Wang, S.M. Applications of Molecular Dynamics Simulation in Protein Study. Membranes 2022, 12, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for All. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information and Reference System for Soil Classification in Russia. Classification of Soils of Russia. 2004. Available online: http://infosoil.ru/index.php?pageID=clas04mode (accessed on 4 November 2025). (In Russian).

- GOST 26213-91; Soils. Methods for Determination of Organic Matter. RussianGost: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1991. Available online: https://www.russiangost.com/p-52750-gost-26213-91.aspx (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- GOST 5180-2015; Soils. Methods for Laboratory Determination of Physical Characteristics. RussianGost: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2015. Available online: https://www.russiangost.com/p-139346-gost-5180-2015.aspx (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- GOST 26423-85; Soils. Methods for Determination of Specific Electric Conductivity, pH and Solid Residue of Water Extract. RussianGost: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1985. Available online: https://www.russiangost.com/p-16105-gost-26423-85.aspx (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- PND F 16.1.41-04; Quantitative Chemical Analysis of Soil. Methods for Measuring the Mass Concentration of Oil Products in Soil Samples by the Gravimetric Method. RussianGost: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2004. Available online: https://www.russiangost.com/p-162428-pnd-f-16141-04.aspx (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Trofimov, S.Y.; Kovaleva, E.I.; Avetov, N.A.; Tolpeshta, I.I. Studies of Oil-Contaminated Soils and Prospective Approaches for Their Remediation. Mosc. Univ. Soil Sci. Bull. 2023, 78, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemtseva, E.V.; Gulnov, D.V.; Gerasimova, M.A.; Sukovatyi, L.A.; Burakova, L.P.; Karuzina, N.E.; Melnik, B.S.; Kratasyuk, V.A. Bacterial Luciferases from Vibrio Harveyi and Photobacterium Leiognathi Demonstrate Different Conformational Stability as Detected by Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires de Oliveira, I.; Caires, A.R.L. Molecular Arrangement in Diesel/Biodiesel Blends: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magsumov, T.; Fatkhutdinova, A.; Mukhametzyanov, T.; Sedov, I. The Effect of Dimethyl Sulfoxide on the Lysozyme Unfolding Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Mechanism. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeier, L.; Oliva, R.; Winter, R. The Multifaceted Effects of DMSO and High Hydrostatic Pressure on the Kinetic Constants of Hydrolysis Reactions Catalyzed by α-Chymotrypsin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 16325–16333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, F.; Hosseinkhani, S.; Khajeh, K. Luciferase Protection against Proteolytic Degradation: A Key for Improving Signal in Nano-System Biology. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 144, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikova, E.G.; Shumkova, E.S.; Shumkov, M.S. Whole-Cell Bacterial Biosensors for the Detection of Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Their Chlorinated Derivatives (Review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2016, 52, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Song, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, W.E.; Li, G.; Deng, S.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, D. Whole-Cell Bioreporters for Evaluating Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contamination. Crit. Rev. Environ. Control 2021, 51, 272–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Close, D.; Smartt, A.; Ripp, S.; Sayler, G. Detection of Organic Compounds with Whole-Cell Bioluminescent Bioassays. In Bioluminescence: Fundamentals and Applications in Biotechnology—Volume 1; Thouand, G., Marks, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 144, pp. 111–151. ISBN 9783662433843. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Z.T.; Weichsel, A.; Montfort, W.R.; Baldwin, T.O. Crystal Structure of the Bacterial Luciferase/Flavin Complex Provides Insight into the Function of the β Subunit. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 6085–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, H.; Sasaki, H.; Kobori, T.; Zenno, S.; Saigo, K.; Murphy, M.E.P.; Adman, E.T.; Tanokura, M. 1.8 Å Crystal Structure of the Major NAD(P)H:FMN Oxidoreductase of a Bioluminescent Bacterium, Vibrio Fischeri: Overall Structure, Cofactor and Substrate-Analog Binding, and Comparison with Related Flavoproteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 280, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeva, A.A.; Nemtseva, E.V.; Kratasyuk, V.A. The Role of Electrostatic Interactions in Complex Formation between Bacterial Luciferase and NADPH:FMN-oxidoreductase. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Biol. 2018, 11, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DMSO-Related Effects in Protein Characterization. Available online: https://www.slas-discovery.org/article/S2472-5552(22)08442-8/pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Chan, D.S.-H.; Kavanagh, M.E.; McLean, K.J.; Munro, A.W.; Matak-Vinković, D.; Coyne, A.G.; Abell, C. Effect of DMSO on Protein Structure and Interactions Assessed by Collision-Induced Dissociation and Unfolding. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 9976–9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, J.; Akke, M. Minute Additions of DMSO Affect Protein Dynamics Measurements by NMR Relaxation Experiments through Significant Changes in Solvent Viscosity. Chem. Phys. Chem 2019, 20, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.-Q.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.-J. Theoretical Study on Role of Aliphatic Aldehyde in Bacterial Bioluminescence. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2021, 419, 113446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakshi; Singh, S.K.; Haritash, A.K. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Soil Pollution and Remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 6489–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titaley, I.A.; Simonich, S.L.M.; Larsson, M. Recent Advances in the Study of the Remediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Compound (PAC)-Contaminated Soils: Transformation Products, Toxicity, and Bioavailability Analyses. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Brassington, K.J.; Prpich, G.; Paton, G.I.; Semple, K.T.; Pollard, S.J.T.; Coulon, F. Insights into the Biodegradation of Weathered Hydrocarbons in Contaminated Soils by Bioaugmentation and Nutrient Stimulation. Chemosphere 2016, 161, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, B.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Ramanayaka, S.; Bolan, N.; Ok, Y.S. The Role of Soils in the Disposition, Sequestration and Decontamination of Environmental Contaminants. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20200177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Protein | Water | 10% DMSO | 10% DMSO + 1.5% Diesel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD, Å | Luciferase | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Reductase | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | |

| Rg, Å | Luciferase | 27.0 ± 0.1 | 27.0 ± 0.1 | 27.0 ± 0.1 |

| Reductase | 21.9 ± 0.1 | 21.8 ± 0.1 | 21.9 ± 0.1 | |

| SASA × 102, Å2 | Luciferase | 297 ± 6 | 297 ± 4 | 302 ± 5 |

| Reductase | 210 ± 4 | 208 ± 3 | 210 ± 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sutormin, O.S.; Lonshakova-Mukina, V.I.; Deeva, A.A.; Gromova, A.A.; Bajbulatov, R.Y.; Kratasyuk, V.A. Dimethyl Sulfoxide as a Biocompatible Extractant for Enzymatic Bioluminescent Toxicity Assays: Experimental Validation and Molecular Dynamics Insights. Toxics 2025, 13, 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121038

Sutormin OS, Lonshakova-Mukina VI, Deeva AA, Gromova AA, Bajbulatov RY, Kratasyuk VA. Dimethyl Sulfoxide as a Biocompatible Extractant for Enzymatic Bioluminescent Toxicity Assays: Experimental Validation and Molecular Dynamics Insights. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121038

Chicago/Turabian StyleSutormin, Oleg S., Victoria I. Lonshakova-Mukina, Anna A. Deeva, Alena A. Gromova, Ruslan Ya. Bajbulatov, and Valentina A. Kratasyuk. 2025. "Dimethyl Sulfoxide as a Biocompatible Extractant for Enzymatic Bioluminescent Toxicity Assays: Experimental Validation and Molecular Dynamics Insights" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121038

APA StyleSutormin, O. S., Lonshakova-Mukina, V. I., Deeva, A. A., Gromova, A. A., Bajbulatov, R. Y., & Kratasyuk, V. A. (2025). Dimethyl Sulfoxide as a Biocompatible Extractant for Enzymatic Bioluminescent Toxicity Assays: Experimental Validation and Molecular Dynamics Insights. Toxics, 13(12), 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121038