Effects of Soil Restoration in Cadmium-Polluted Areas on Body Cadmium Burden and Renal Tubular Damage in Inhabitants in Japan

Highlights

- Soil restoration has a substantial impact on the reduction in lifetime cadmium (LCd) intake in residents of contaminated areas, with a decrease of approximately 2g.

- Additionally, the restoration process decreases cadmium body burden and renal tubular damage.

- This provides strong evidence for soil restoration as a critical strategy to protect public health in Cd-polluted regions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

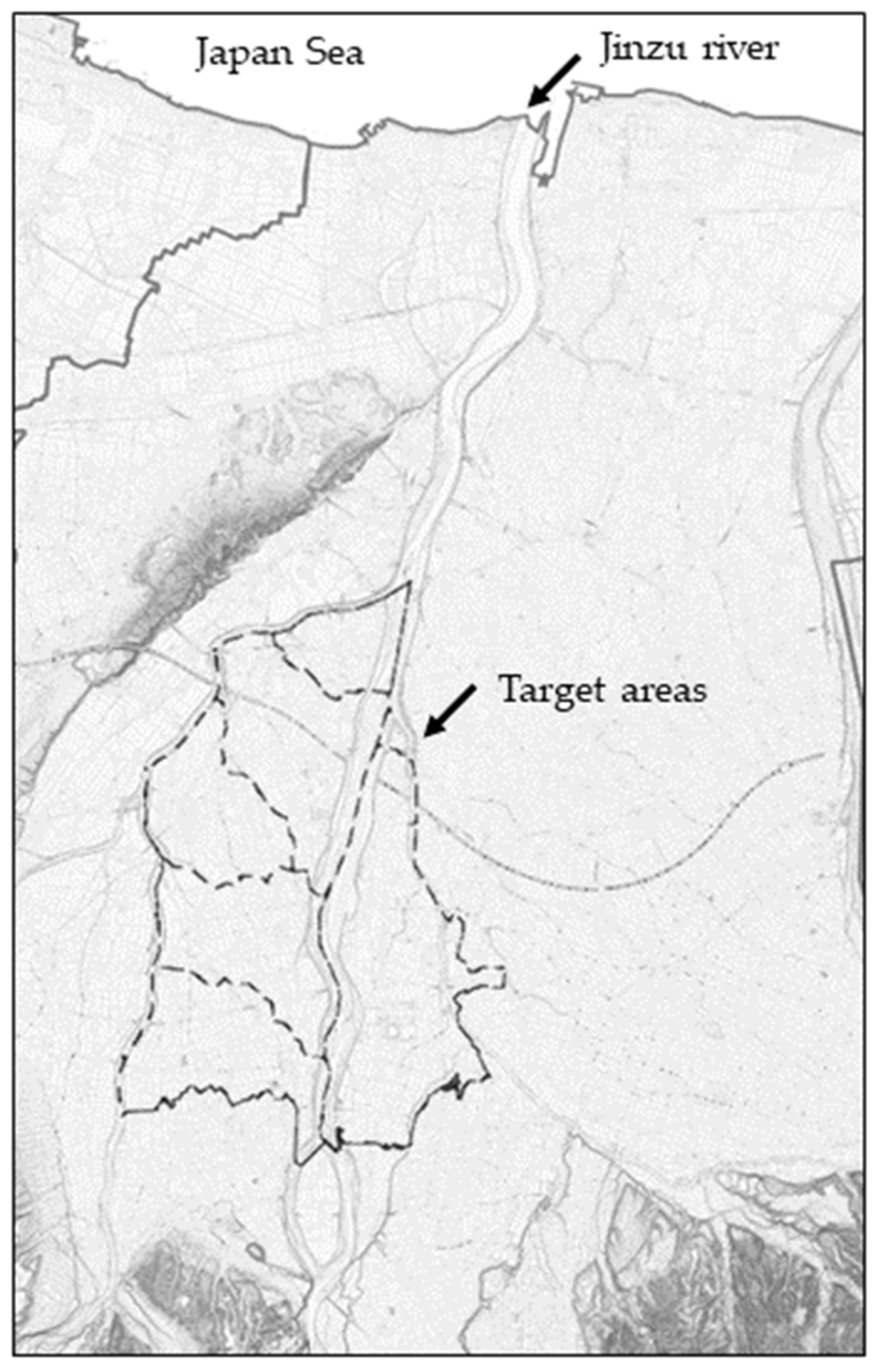

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Lifetime Cd Intake

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Cr | Creatinine |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| LCd | Lifetime Cd |

| U-β2MG | Urinary β2-microglobulin |

| U-Cd | Urinary Cd |

References

- Aoshima, K.; Horiguchi, H. Historical Lessons on Cadmium Environmental Pollution Problems in Japan and Current Cadmium Exposure Situation. In Cadmium Toxicity: New Aspects in Human Disease, Rice Contamination, and Cytotoxicity; Himeno, S., Aoshima, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg, G.F.; Bernard, A.; Damond, G.L.; Duffus, J.H.; Illing, P.; Nordberg, M.; Bergdahl, I.A.; Jin, T.; Skerfving, S. Risk assessment of effects of cadmium on human health (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2018, 90, 755–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoshima, K. Itai-itai disease: Renal tubular osteomalacia induced by environmental exposure to cadmium—Historical review and perspectives. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 62, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, M. Heavy metal pollution and methods of restoration of polluted soil in the Jinzu River basin. Bull. Toyama Agric. Exp. Stn. 1984, 15, 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- Aoshima, K. Recent Clinical and Epidemiological Studies of Itai-Itai Disease (Cadmium-Induced Renal Tubular Osteomalacia) and Cadmium Nephropathy in the Jinzu River Basin in Toyama Prefecture, Japan. In Cadmium Toxicity: New Aspects in Human Disease, Rice Contamination, and Cytotoxicity; Himeno, S., Aoshima, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya, M. Recent epidemiological studies on itai-itai disease as a chronic cadmium poisoning in Japan. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 42, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, M.; Suwazono, Y.; Nogawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Takami, M.; Ogra, Y.; Tanaka, Y.K.; Iwase, H.; Tanaka, K.; Ishizaki, M.; et al. Cadmium body burden and health effects after restoration of cadmium-polluted soils in cadmium-polluted areas in the Jinzu River basin. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2023, 28, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Shao, S.; Ni, H.; Fu, Z.; Hu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Min, X.; She, S.; Chen, S.; Huang, M.; et al. Current status, spatial features, health risks, and potential driving factors of soil heavy metal pollution in China at province level. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 114961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, G.; Ding, X.; Jin, T. The references level of cadmium intake for renal dysfunction in a Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Limpatanachote, P.; Mahasakpan, P.; Krintratun, S.; Padungtod, C. Cadmium-exposed population in Mae Sot District, Tak Province: 1. Prevalence of high urinary cadmium levels in the adults. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2007, 90, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Nguntra, P.; Kaewnate, Y.; Mahasakpan, P.; Limpatanachote, P.; Aunjai, T.; Jeekeeree, W.; Punta, B.; Funkhiew, T.; Phopueng, I. Human Health Effects from Cadmium Exposure: Comparison between Persons Living in Cadmium-Contaminated and Non-Contaminated Areas in Northwestern Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2015, 46, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Toyama Prefectural Department of Health and Welfare. Current Status of Polution of Soil And its Countermeasure: An Interpretation of White Paper on Environmental Pollution; Toyama Prefecture: Toyama, Japan, 1976; pp. 128–133. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, T.; Kobayashi, E.; Okubo, Y.; Suwazono, Y.; Kido, T.; Nogawa, K. Relationship among prevalence of patients with Itai-itai disease, prevalence of abnormal urinary findings, and cadmium concentrations in rice of individual hamlets in the Jinzu River basin, Toyama prefecture of Japan. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2004, 14, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogawa, K.; Honda, R.; Kido, T.; Tsuritani, I.; Yamada, Y.; Ishizaki, M.; Yamaya, H. A dose-response analysis of cadmium in the general environment with special reference to total cadmium intake limit. Environ. Res. 1989, 48, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arisawa, K.; Nakano, A.; Saito, H.; Liu, X.J.; Yokoo, M.; Soda, M.; Koba, T.; Takahashi, T.; Kinoshita, K. Mortality and cancer incidence among a population previously exposed to environmental cadmium. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2001, 74, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, K.; Saito, H.; Nakano, A. Association between cadmium-induced renal dysfunction and mortality: Further evidence. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 1991, 164, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, K.; Saito, H.; Moriyama, M.; Nakano, A. Follow up study of renal tubular dysfunction and mortality in residents of an area polluted with cadmium. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1992, 49, 736–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, K.; Saito, H.; Moriyama, M.; Nakano, A. Association between renal tubular dysfunction and mortality among residents in a cadmium-polluted area, Nagasaki, Japan. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 1991, 164, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arisawa, K.; Uemura, H.; Hiyoshi, M.; Dakeshita, S.; Kitayama, A.; Saito, H.; Soda, M. Cause-specific mortality and cancer incidence rates in relation to urinary beta2-microglobulin: 23-year follow-up study in a cadmium-polluted area. Toxicol. Lett. 2007, 173, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, A.; Michaëlsson, K.; Vahter, M.; Julin, B.; Wolk, A.; Åkesson, A. Associations between dietary cadmium exposure and bone mineral density and risk of osteoporosis and fractures among women. Bone 2012, 50, 1372–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.D.; Michaelsson, K.; Julin, B.; Wolk, A.; Akesson, A. Dietary cadmium exposure and fracture incidence among men: A population-based prospective cohort study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julin, B.; Wolk, A.; Johansson, J.E.; Andersson, S.O.; Andren, O.; Akesson, A. Dietary cadmium exposure and prostate cancer incidence: A population-based prospective cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julin, B.; Wolk, A.; Akesson, A. Dietary cadmium exposure and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in a prospective cohort of Swedish women. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julin, B.; Wolk, A.; Bergkvist, L.; Bottai, M.; Akesson, A. Dietary cadmium exposure and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: A population-based prospective cohort study. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkesson, A.; Julin, B.; Wolk, A. Long-term Dietary Cadmium Intake and Postmenopausal Endometrial Cancer Incidence: A Population-Based Prospective Cohort Study. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Cadmium and cadmium compounds. In Arsenic, Metals, Fibres and Dusts. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2012; Volume 100C, pp. 121–145. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, H.; Iwasaki, M.; Sawada, N.; Takachi, R.; Kasuga, Y.; Yokoyama, S.; Onuma, H.; Nishimura, H.; Kusama, R.; Yokoyama, K.; et al. Dietary cadmium intake and breast cancer risk in Japanese women: A case-control study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavado-Garcia, J.M.; Puerto-Parejo, L.M.; Roncero-Martin, R.; Moran, J.M.; Pedrera-Zamorano, J.D.; Aliaga, I.J.; Leal-Hernandez, O.; Canal-Macias, M.L. Dietary Intake of Cadmium, Lead and Mercury and Its Association with Bone Health in Healthy Premenopausal Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto-Parejo, L.M.; Aliaga, I.; Canal-Macias, M.L.; Leal-Hernandez, O.; Roncero-Martin, R.; Rico-Martin, S.; Moran, J.M. Evaluation of the Dietary Intake of Cadmium, Lead and Mercury and Its Relationship with Bone Health among Postmenopausal Women in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Suwazono, Y.; Uetani, M.; Inaba, T.; Oishi, M.; Kido, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Nogawa, K. Association between lifetime cadmium intake and cadmium concentration in individual urine. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2005, 74, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, T.; Sunaga, K.; Nishijo, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Kobayashi, E.; Nogawa, K. The relation of individual cadmium concentration in urine with total cadmium intake in Kakehashi River basin, Japan. Toxicol. Lett. 2004, 152, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, K.; Kobayashi, E.; Okubo, Y.; Suwazono, Y.; Kido, T.; Nishijo, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Nogawa, K. Total cadmium intake and mortality among residents in the Jinzu River Basin, Japan. Arch. Environ. Health 2003, 58, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, K.; Nogawa, K.; Kido, T.; Nishijo, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Suwazono, Y. Estimation of Benchmark Dose of Lifetime Cadmium Intake for Adverse Renal Effects Using Hybrid Approach in Inhabitants of an Environmentally Exposed River Basin in Japan. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Lei, L.; Nilsson, J.; Li, H.; Nordberg, M.; Bernard, A.; Nordberg, G.F.; Bergdahl, I.A.; Jin, T. Renal function after reduction in cadmium exposure: An 8-year follow-up of residents in cadmium-polluted areas. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zug, K.L.M.; Huamaní Yupanqui, H.A.; Meyberg, F.; Cierjacks, J.S.; Cierjacks, A. Cadmium Accumulation in Peruvian Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) and Opportunities for Mitigation. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Safety Evaluation of Certain Contaminants in Food: Prepared by the Ninety-First Meeting of The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA); WHO Food Additives Series, No. 82; World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.; Plant, J.A.; Voulvoulis, N.; Oates, C.J.; Ihlenfeld, C. Cadmium levels in Europe: Implications for human health. Environ. Geochem. Health 2010, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, H.; Oguma, E.; Sasaki, S.; Miyamoto, K.; Hosoi, Y.; Ono, A.; Kayama, F. Exposure Assessment of Cadmium in Female Farmers in Cadmium-Polluted Areas in Northern Japan. Toxics 2020, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.L.; Phuc, H.D.; Okamoto, R.; Kido, T.; Oanh, N.T.P.; Manh, H.D.; Anh, L.T.; Ichimori, A.; Nogawa, K.; Suwazono, Y.; et al. A 30-year follow-up study in a former cadmium-polluted area of Japan: The relationship between cadmium exposure and beta(2)-microglobulin in the urine of Japanese people. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 23079–23085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc Phuc, H.; Kido, T.; Dung Manh, H.; Thai Anh, L.; Phuong Oanh, N.T.; Okamoto, R.; Ichimori, A.; Nogawa, K.; Suwazono, Y.; Nakagawa, H. A 28-year observational study of urinary cadmium and beta(2)-microglobulin concentrations in inhabitants in cadmium-polluted areas in Japan. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2016, 36, 1622–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain on a request from the European Commission on cadmium in food. EFSA J. 2009, 980, 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants: Seventy-Third [73rd] Report of The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; WHO Technical Report Series, No. 960; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Men (n = 991) | Women (n = 828) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD 1 | Mean | SD 1 |

| Lifetime Cd intake, g | 2.07 | 1.39 | 1.71 | 1.13 |

| Age, years | 60.4 | 15.9 | 58.8 | 17.0 |

| Duration of residence in the polluted area, years | 17.0 | 20.0 | 11.0 | 15.7 |

| GM 2 | GSD 3 | GM 2 | GSD 3 | |

| U-Cd 4, µg/g Cr | 0.98 | 2.15 | 1.53 | 2.24 |

| U-β2MG 5, µg/g Cr | 174 | 3.16 | 200 | 3.03 |

| U-Cr 6, g/L | 0.99 | 1.73 | 0.72 | 1.87 |

| N | % | N | % | |

| U-β2MG 5 ≥ 300 µg/g Cr | 203 | 20.5% | 169 | 20.4% |

| U-β2MG 5 ≥ 1000 µg/g Cr | 69 | 7.0% | 55 | 6.6% |

| Nonsmoker | 289 | 29.2% | 707 | 85.4% |

| Ex-smoker | 487 | 49.1% | 96 | 11.6% |

| Smoker | 215 | 21.7% | 25 | 3.0% |

| U-Cd 1, µg/g Cr | Increase (95% CI 2) | p | R 2 | VIF 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 991) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 1.30-fold (1.27–1.34) | <0.001 | 0.287 | 1.015 |

| Ex-smoker (/nonsmoker 4) | 1.40-fold (1.27–1.54) | <0.001 | 1.385 | ||

| Smoker (/nonsmoker 4) | 1.20-fold (1.07–1.34) | 0.002 | 1.374 | ||

| Women (n = 828) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 1.43-fold (1.37–1.49) | <0.001 | 0.244 | 1.000 |

| U-β2MG 5, µg/g Cr | Increase (95% CI) | p | |||

| Men (n = 991) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 1.35-fold (1.29–1.42) | <0.001 | 0.133 | 1.000 |

| Women (n = 828) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 1.51-fold (1.42–1.60) | <0.001 | 0.172 | 1.000 |

| Men (n = 503) | Women (n = 342) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI 1) | p | Mean (95% CI 1) | p | |

| Expected lifetime Cd intake without soil restoration, g | 5.06 (4.92–5.19) | <0.001 | 4.57 (4.41–4.73) | <0.001 |

| Lifetime Cd intake, g | 2.99 (2.88–3.11) | 2.59 (2.47–2.72) | ||

| Estimated decrease in lifetime Cd intake associated with soil restoration, g | 2.06 (1.98–2.14) | 1.98 (1.89–2.07) | ||

| GM 2 (95% CI 1) | p | GM (95% CI 1) | p | |

| Expected U-Cd 3 without soil restoration, µg/g Cr | 2.18 (2.09–2.26) | <0.001 | 4.22 (3.99–4.47) | <0.001 |

| U-Cd 3, µg/g Cr | 1.23 (1.16–1.31) | 1.99 (1.85–2.14) | ||

| U-Cd 3 divided by expected U-Cd 3 without soil restoration | 0.57 (0.54–0.60) | 0.47 (0.44–0.51) | ||

| Expected U-β2MG 4 without soil restoration, µg/g Cr | 430 (413–448) | <0.001 | 646 (605–689) | <0.001 |

| U-β2MG 4, µg/g Cr | 213 (191–238) | 256 (223–294) | ||

| U-β2MG 4 divided by expected U-β2MG 4 without soil restoration | 0.50 (0.45–0.55) | 0.40 (0.35–0.45) | ||

| U-β2MG 1 ≥ 300 µg/g Cr | Odds Ratio (95% CI 2) | p | Nagelkerke R 2 | |

| Men (n = 991) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 1.75 (1.57–1.96) | <0.001 | 0.119 |

| Women (n = 828) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 1.84 (1.59–2.13) | <0.001 | 0.172 |

| U-β2MG 1 ≥ 1000 µg/g Cr | Odds ratio (95% CI 2) | p | Nagelkerke R 2 | |

| Men (n = 991) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 1.71 (1.47–2.00) | <0.001 | 0.158 |

| Women (n = 828) | Lifetime Cd intake, +1 g | 2.15 (1.76–2.64) | <0.001 | 0.129 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nogawa, K.; Sakurai, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Ishizaki, M.; Ogra, Y.; Tanaka, Y.-K.; Iwase, H.; Tanaka, K.; Kido, T.; Nakagawa, H.; et al. Effects of Soil Restoration in Cadmium-Polluted Areas on Body Cadmium Burden and Renal Tubular Damage in Inhabitants in Japan. Toxics 2025, 13, 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121010

Nogawa K, Sakurai M, Watanabe Y, Ishizaki M, Ogra Y, Tanaka Y-K, Iwase H, Tanaka K, Kido T, Nakagawa H, et al. Effects of Soil Restoration in Cadmium-Polluted Areas on Body Cadmium Burden and Renal Tubular Damage in Inhabitants in Japan. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121010

Chicago/Turabian StyleNogawa, Kazuhiro, Masaru Sakurai, Yuuka Watanabe, Masao Ishizaki, Yasumitsu Ogra, Yu-Ki Tanaka, Hirotaro Iwase, Kayo Tanaka, Teruhiko Kido, Hideaki Nakagawa, and et al. 2025. "Effects of Soil Restoration in Cadmium-Polluted Areas on Body Cadmium Burden and Renal Tubular Damage in Inhabitants in Japan" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121010

APA StyleNogawa, K., Sakurai, M., Watanabe, Y., Ishizaki, M., Ogra, Y., Tanaka, Y.-K., Iwase, H., Tanaka, K., Kido, T., Nakagawa, H., Suwazono, Y., & Nogawa, K. (2025). Effects of Soil Restoration in Cadmium-Polluted Areas on Body Cadmium Burden and Renal Tubular Damage in Inhabitants in Japan. Toxics, 13(12), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121010