Neurotoxicity Assessment of Perfluoroundecanoic Acid (PFUnDA) in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Preparation

2.2. Husbandry and Egg Production of Zebrafish

2.3. PFUnDA Exposure Design

2.4. Acridine Orange

2.5. Reactive Oxygen Species

2.6. Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.7. Visual Motor Response Test

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survival and Deformity

3.2. Acridine Orange

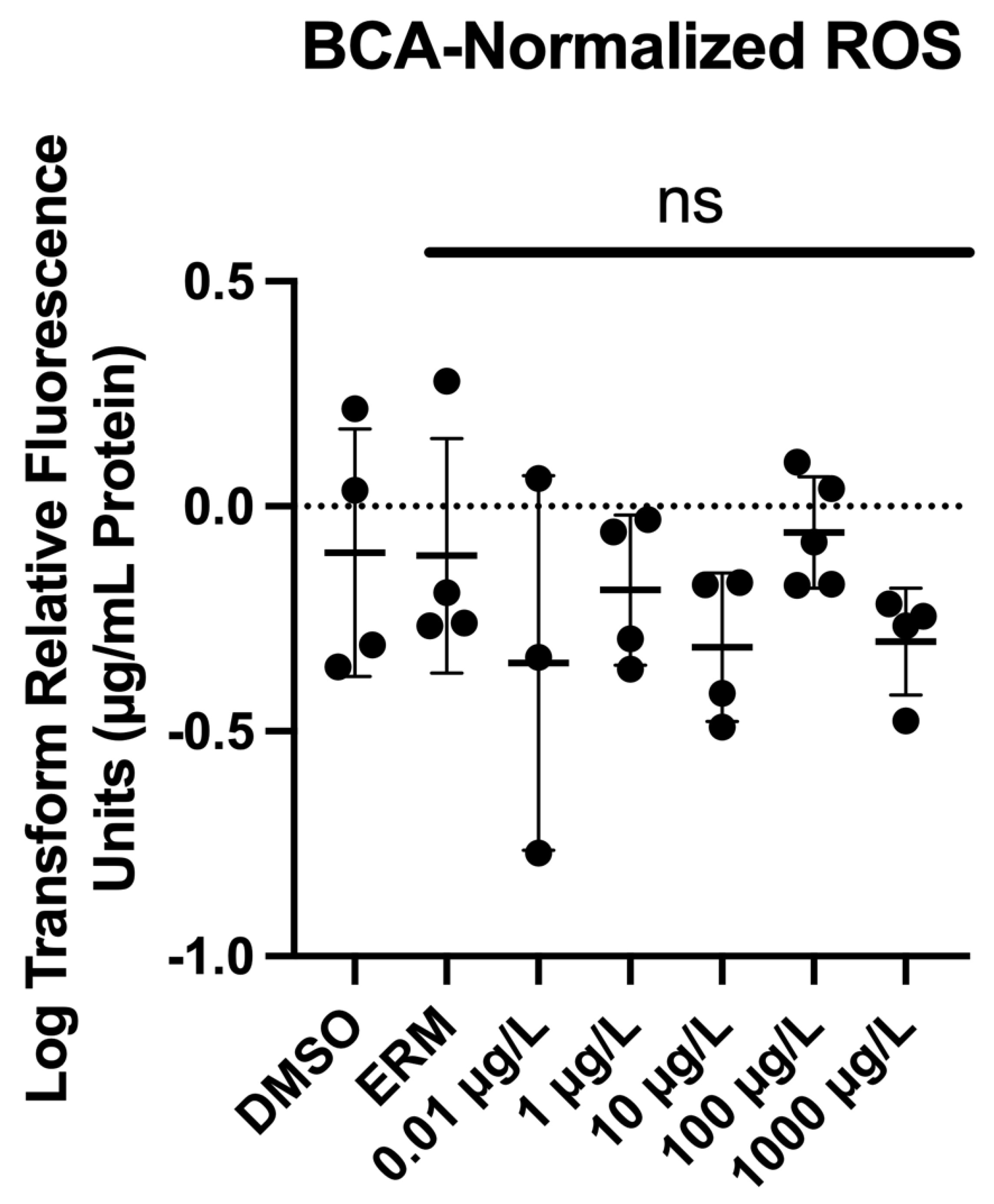

3.3. Reactive Oxygen Species

3.4. Real-Time PCR Analysis

3.5. Locomotion Activity with Visual Motor Response Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AO | Acridine orange |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| CDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| Cq | Cycle Threshold |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DPF | Days post fertilization |

| ERM | Embryo rearing media |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| HPF | Hours post fertilization |

| H2-DCFDA | 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| NRT | No reverse transcriptase |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PFASs | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFBA | Perfluorobutanoic acid |

| PFDoA | Perfluorododecanoic acid |

| PFNA | Perfluorononanoic acid |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid |

| PFTeDA | Perfluorotetradecanoic acid |

| PFUnDA | Perfluoroundecanoic acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| USA | United States of America |

| VMR | Visual Motor Response |

| ZIRC | Zebrafish International Resource Center |

References

- Xu, Y.; Fletcher, T.; Pineda, D.; Lindh, C.H.; Nilsson, C.; Glynn, A.; Vogs, C.; Norström, K.; Lilja, K.; Jakobsson, K. Serum half-lives for short-and long-chain perfluoroalkyl acids after ceasing exposure from drinking water contaminated by firefighting foam. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 077004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Song, S.; Hu, C.; Liu, M.; Lam, P.K.; Zhou, B.; Lam, J.C.; Chen, L. Parental exposure to perfluorobutane sulfonate disturbs the transfer of maternal transcripts and offspring embryonic development in zebrafish. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coperchini, F.; Croce, L.; Ricci, G.; Magri, F.; Rotondi, M.; Imbriani, M.; Chiovato, L. Thyroid disrupting effects of old and new generation PFAS. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11, 612320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, C.B.; Angerer, T.B.; Robert, H.; Poupin, N.; Lakhal, L.; Frache, G.; Mercier-Bonin, M.; Audinot, J.-N. Lipidomic profiling of PFOA-exposed mouse liver by multi-modal mass spectrometry analysis. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 6568–6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Fu, L.; Cao, M.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Guo, A.; Zhong, H.; Li, W.; Liang, Y. PFAS-induced lipidomic dysregulations and their associations with developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 861, 160691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, W.S.; Hopkins, J.G.; Richards, S.M. A review of per-and polyfluorinated alkyl substance impairment of reproduction. Front. Toxicol. 2021, 3, 732436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Son, Y. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in surface water and sediments from two urban watersheds in Nevada, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrow, S.M.; Ruppel, B.; Lippincott, R.L.; Post, G.B.; Procopio, N.A. Investigation of levels of perfluoroalkyl substances in surface water, sediment and fish tissue in New Jersey, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.G.; Antonison, A.; Oldnettle, A.; Costa, K.A.; Timshina, A.S.; Ditz, H.; Thompson, J.T.; Holden, M.M.; Sobczak, W.J.; Arnold, J. Statewide Surveillance and Mapping of PFAS in Florida Surface Water. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 4343–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, E.K.; Hall, L.M.; Brown, M.A.; Taylor-Manges, A.; Green, T.; Suchanec, K.; Furman, B.T.; Congdon, V.M.; Wilson, S.S.; Osborne, T.Z. PFAS surveillance in abiotic matrices within vital aquatic habitats throughout Florida. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 192, 115011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivantsova, E.; Sultan, A.; Martyniuk, C.J. Occurrence and Toxicity Mechanisms of Perfluorononanoic Acid, Perfluorodecanoic Acid, and Perfluoroundecanoic Acid in Fish: A Review. Toxics 2025, 13, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Hua, X.; Zhang, B.; Tang, C.; An, X.; Lin, T. Emerging and legacy perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in surface water around three international airports in China. Chemosphere 2023, 344, 140360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Han, T.; Li, B.; Bai, P.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y. Distribution Control and Environmental Fate of PFAS in the Offshore Region Adjacent to the Yangtze River Estuary—A Study Combining Multiple Phases Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 15779–15789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naile, J.E.; Khim, J.S.; Wang, T.; Chen, C.; Luo, W.; Kwon, B.-O.; Park, J.; Koh, C.-H.; Jones, P.D.; Lu, Y. Perfluorinated compounds in water, sediment, soil and biota from estuarine and coastal areas of Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörengård, M.; Bergström, S.; McCleaf, P.; Wiberg, K.; Ahrens, L. Long-distance transport of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in a Swedish drinking water aquifer. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 311, 119981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.; Kärrman, A.; Yeung, L.W.; Jonsson, M.; Ahrens, L.; Wang, T. Point source characterization of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and extractable organofluorine (EOF) in freshwater and aquatic invertebrates. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2019, 21, 1887–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kärrman, A.; Elgh-Dalgren, K.; Lafossas, C.; Møskeland, T. Environmental levels and distribution of structural isomers of perfluoroalkyl acids after aqueous fire-fighting foam (AFFF) contamination. Environ. Chem. 2011, 8, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasier, P.J.; Washington, J.W.; Hassan, S.M.; Jenkins, T.M. Perfluorinated chemicals in surface waters and sediments from northwest Georgia, USA, and their bioaccumulation in Lumbriculus variegatus. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2011, 30, 2194–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, G.; Mercier, L.; Duy, S.V.; Liu, J.; Sauvé, S.; Houde, M. Bioaccumulation and trophic magnification of emerging and legacy per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in a St. Lawrence River Food web. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119739. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, D.A.; Abessa, D.M.; Moreira, L.B.; Maranho, L.A.; Oliveira, L.G.; Benskin, J.P.; Leonel, J. Spatial and temporal distribution of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) detected after an aqueous film forming foam (AFFF) spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 204, 116561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delinsky, A.D.; Strynar, M.J.; Nakayama, S.F.; Varns, J.L.; Ye, X.; McCann, P.J.; Lindstrom, A.B. Determination of ten perfluorinated compounds in bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus) fillets. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, L.L.; Snyder, B.D.; Olsen, A.R.; Kincaid, T.M.; Wathen, J.B.; McCarty, H.B. Perfluorinated compounds in fish from US urban rivers and the Great Lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 499, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fair, P.A.; Wolf, B.; White, N.D.; Arnott, S.A.; Kannan, K.; Karthikraj, R.; Vena, J.E. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in edible fish species from Charleston Harbor and tributaries, South Carolina, United States: Exposure and risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Cai, Y. Tissue distribution of perfluorinated compounds in farmed freshwater fish and human exposure by consumption. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012, 31, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horzmann, K.A.; Freeman, J.L. Making waves: New developments in toxicology with the zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 163, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerfield, M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio); University of Oregon Press: Eugene, OR, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Souders, C.L., II; Wang, S.; Ganter, J.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.H.; Cheng, H.; Martyniuk, C.J. Behavioral and developmental toxicity assessment of the strobilurin fungicide fenamidone in zebrafish embryos/larvae (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 112966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Rodriguez, V.; Souders, C.L., II; Tischuk, C.; Martyniuk, C.J. Tebuconazole reduces basal oxidative respiration and promotes anxiolytic responses and hypoactivity in early-staged zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 217, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, C.B.; Ballard, W.W.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ullmann, B.; Schilling, T.F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 1995, 203, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 236: Fish embryo acute toxicity (FET) test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Adamovsky, O.; Souders, C.L., II; Martyniuk, C.J. Biological effects of the benzotriazole ultraviolet stabilizers UV-234 and UV-320 in early-staged zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Souders, C.L., II; Zhao, Y.H.; Martyniuk, C.J. Paraquat affects mitochondrial bioenergetics, dopamine system expression, and locomotor activity in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2018, 191, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, W.; Fu, Z. Effect of endocrine disrupting chemicals on the transcription of genes related to the innate immune system in the early developmental stage of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 28, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Di, S.; Yu, Y.; Qi, P.; Wang, X.; Jin, Y. 6PPD induced cardiac dysfunction in zebrafish associated with mitochondrial damage and inhibition of autophagy processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffioli, E.; Angiulli, E.; Nonnis, S.; Grassi Scalvini, F.; Negri, A.; Tedeschi, G.; Arisi, I.; Frabetti, F.; D’Aniello, S.; Alleva, E. Brain proteome and behavioural analysis in wild type, BDNF+/− and BDNF−/− adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) exposed to two different temperatures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Low dose of arsenic trioxide triggers oxidative stress in zebrafish brain: Expression of antioxidant genes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 107, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Wagh, G.; Mokalled, M.H.; Kontarakis, Z.; Dickson, A.L.; Rayrikar, A.; Günther, S.; Poss, K.D.; Stainier, D.Y.; Patra, C. Ccn2a is an injury-induced matricellular factor that promotes cardiac regeneration in zebrafish. Development 2021, 148, dev193219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Deng, P.; Xing, D.; Liu, H.; Shi, F.; Hu, L.; Zou, X.; Nie, H.; Zuo, J.; Zhuang, Z. Developmental Neurotoxicity of Difenoconazole in Zebrafish Embryos. Toxics 2023, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Sun, H.; Xu, Z.; Hong, H.; Lin, H.; Gao, P. 3-bromocarbazole-induced developmental neurotoxicity and effect mechanisms in zebrafish. ACS EST Water 2023, 3, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Y.; Zeng, W.-L.; Ye, Y.-W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M.-M.; Chen, Y.-S.; Liu, C.-T.; Zhong, Z.-Q.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Glia maturation factor-β in hepatocytes enhances liver regeneration and mitigates steatosis and ballooning in zebrafish. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2025, 329, G291–G306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Li, X.; Gao, M.; Ji, S.; Tian, W.; Ji, G.; Du, J.; Hao, A. SOX19b regulates the premature neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells through EZH2-mediated histone methylation in neural tube development of zebrafish. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Mo, C.; Tu, P.; Ning, N.; Liu, X.; Lin, S.; Muthulakshmi, S.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K. Developmental toxicity of Zishen Guchong Pill on the early life stages of Zebrafish. Phytomed. Plus 2021, 1, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gong, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Hu, N.; Dai, X.; Peng, C.; Li, Y. Quercetin mitigates ethanol-induced hepatic steatosis in zebrafish via P2X7R-mediated PI3K/Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 268, 113569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Liu, J.; Zeng, X.; Yu, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, J. Tris (2-butoxyethyl) phosphate affects motor behavior and axonal growth in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 198, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.-Y.; Cowden, J.; Simmons, S.O.; Padilla, S.; Ramabhadran, R. Gene expression changes in developing zebrafish as potential markers for rapid developmental neurotoxicity screening. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2010, 32, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCurley, A.T.; Callard, G.V. Characterization of housekeeping genes in zebrafish: Male-female differences and effects of tissue type, developmental stage and chemical treatment. BMC Mol. Biol. 2008, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Yan, W.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Yu, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, G. Microcystin-LR exposure induces developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish embryo. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 213, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, S.; Souders, C.L.; Ivantsova, E.; Wengrovitz, A.; Ganter, J.; Zhao, Y.H.; Cheng, H.; Martyniuk, C.J. Exposure to acetochlor impairs swim bladder formation, induces heat shock protein expression, and promotes locomotor activity in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 112978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivantsova, E.; Konig, I.; Lopez-Scarim, V.; English, C.; Charnas, S.R.; Souders, C.L., II; Martyniuk, C.J. Molecular and behavioral toxicity assessment of tiafenacil, a novel PPO-inhibiting herbicide, in zebrafish embryos/larvae. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2023, 98, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, G.; Lee, Y.-M.; Zoh, K.-D.; Choi, K. Thyroid disrupting effects of perfluoroundecanoic acid and perfluorotridecanoic acid in zebrafish (Danio rerio) and rat pituitary (GH3) cell line. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, K.; Dai, J.; Zhao, Y. Comparative developmental toxicities of zebrafish towards structurally diverse per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantzen, C.E.; Annunziato, K.A.; Bugel, S.M.; Cooper, K.R. PFOS, PFNA, and PFOA sub-lethal exposure to embryonic zebrafish have different toxicity profiles in terms of morphometrics, behavior and gene expression. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 175, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Sheng, N.; Zhang, W.; Dai, J. Toxic effects of perfluorononanoic acid on the development of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 32, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, M.; Sun, W.; Cheng, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H. Transcriptome-based analysis reveals the toxic effects of perfluorononanoic acid by affecting the development of the cardiovascular system and lipid metabolism in zebrafish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 289, 110108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Xu, B.; Magnuson, J.T.; Xu, E.G.; Wu, M.; Zheng, C. Poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances induce immunotoxicity via the TLR pathway in zebrafish: Links to carbon chain length. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 6139–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, S.; Ren, Z.; Jiao, X.; Qin, S. Induction of oxidative stress and related transcriptional effects of perfluorononanoic acid using an in vivo assessment. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 160, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainieri, S.; Conlledo, N.; Langerholc, T.; Madorran, E.; Sala, M.; Barranco, A. Toxic effects of perfluorinated compounds at human cellular level and on a model vertebrate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 104, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, N.; Ivantsova, E.; Konig, I.; English, C.D.; Avidan, L.; Kreychman, M.; Rivera, M.L.; Escobar, C.; Valle, E.M.A.; Sultan, A. Adverse Outcomes Following Exposure to Perfluorooctanesulfonamide (PFOSA) in Larval Zebrafish (Danio rerio): A Neurotoxic and Behavioral Perspective. Toxics 2024, 12, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, S.E.; Martin, N.R.; Rodd, A.; Manz, K.E.; Allen, E.; Camarillo, M.; Weller, H.I.; Pennell, K.; Plavicki, J.S. Evaluation of neural regulation and microglial responses to brain injury in larval zebrafish exposed to perfluorooctane sulfonate. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 117008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Ivantsova, E.; Konig, I.; Souders, C.L.; Martyniuk, C.J. Perfluorotetradecanoic Acid (PFTeDA) Induces Mitochondrial Damage and Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryos/Larvae. Toxics 2022, 10, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, M.; Chu, W. Neurotoxicity and intestinal microbiota dysbiosis induced by per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in crucian carp (Carassius auratus). J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Junaid, M.; Ahmad, M.; Bi, C.; Guo, W.; Liu, S. Chronic environmental level exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate overshadows graphene oxide to induce apoptosis through activation of the ROS-p53-caspase pathway in marine medaka Oryzias melastigma. Chemosphere 2024, 365, 143374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Yang, D.; Hu, B.; Zha, W.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Liao, X.; Li, H.; Tao, Q. Perfluorodecanoic acid induces the increase of innate cells in zebrafish embryos by upregulating oxidative stress levels. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 287, 110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponder, K.G.; Boise, L.H. The prodomain of caspase-3 regulates its own removal and caspase activation. Cell Death Discov. 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Lam, P.K.; Wu, R.S.; Zhou, B. Induction of oxidative stress and apoptosis by PFOS and PFOA in primary cultured hepatocytes of freshwater tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquat. Toxicol. 2007, 82, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, D.; Magnuson, J.T.; Xu, B.; Zheng, C.; Schlenk, D.; Tang, L.; Qiu, W. Perfluorodecanoic Acid (PFDA) Disrupts Immune Regulation via the Toll-like Receptor Signaling Pathway in Zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 19119–19130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathina, S.; Das, U.N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its clinical implications. Arch. Med. Sci. 2015, 11, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurga, A.M.; Paleczna, M.; Kadluczka, J.; Kuter, K.Z. Beyond the GFAP-astrocyte protein markers in the brain. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Fong, T.; Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Luo, P.; Xie, H. Glia maturation factor-β: A potential therapeutic target in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucenas, S.; Snell, H.; Appel, B. nkx2.2a promotes specification and differentiation of a myelinating subset of oligodendrocyte lineage cells in zebrafish. Neuron Glia Biol. 2008, 4, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rericha, Y.; Cao, D.; Truong, L.; Simonich, M.; Field, J.A.; Tanguay, R.L. Behavior effects of structurally diverse per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in zebrafish. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rericha, Y.; Cao, D.; Truong, L.; Simonich, M.T.; Field, J.A.; Tanguay, R.L. Sulfonamide functional head on short-chain perfluorinated substance drives developmental toxicity. iScience 2022, 25, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulhaq, M.; Örn, S.; Carlsson, G.; Morrison, D.A.; Norrgren, L. Locomotor behavior in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae exposed to perfluoroalkyl acids. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 144, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avidan, L.; English, C.D.; Ivantsova, E.; Sultan, A.; Martyniuk, C.J. Neurotoxicity Assessment of Perfluoroundecanoic Acid (PFUnDA) in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxics 2025, 13, 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121012

Avidan L, English CD, Ivantsova E, Sultan A, Martyniuk CJ. Neurotoxicity Assessment of Perfluoroundecanoic Acid (PFUnDA) in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121012

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvidan, Lev, Cole D. English, Emma Ivantsova, Amany Sultan, and Christopher J. Martyniuk. 2025. "Neurotoxicity Assessment of Perfluoroundecanoic Acid (PFUnDA) in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio)" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121012

APA StyleAvidan, L., English, C. D., Ivantsova, E., Sultan, A., & Martyniuk, C. J. (2025). Neurotoxicity Assessment of Perfluoroundecanoic Acid (PFUnDA) in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxics, 13(12), 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121012