The Effects of Environmental Legislation via Green Procurement Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

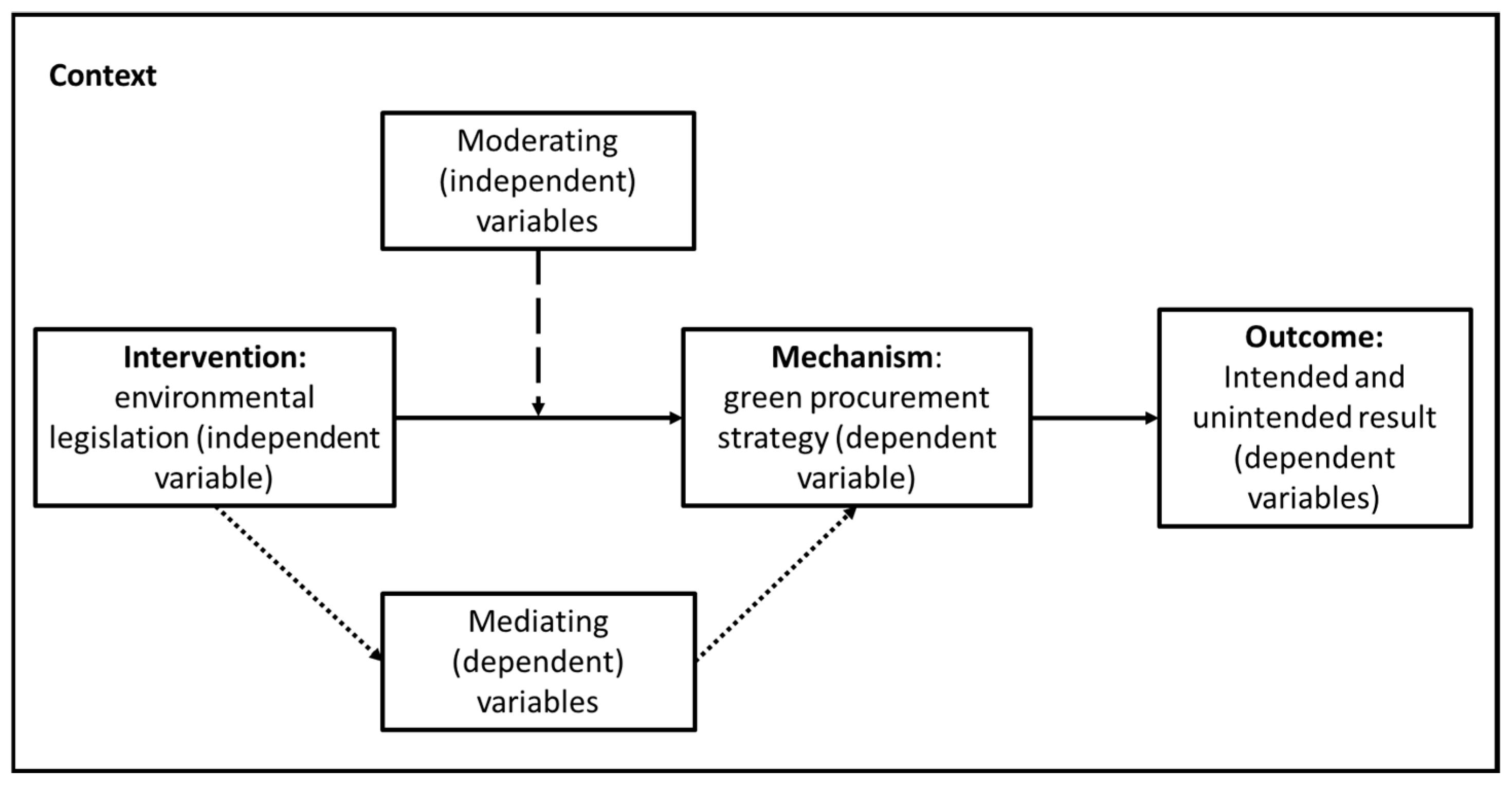

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Step 1: Define Research Question by Decisions 1, 2, and 3

2.2. Step 2: Determining the Required Characteristics of Primary Studies by Decision 4

2.3. Step 3: Retrieving a Sample of Potentially Relevant Literature by Decisions 5 and 6

2.4. Step 4: Selecting the Pertinent Literature by Decision 7

2.5. Step 5 and 6: Synthesizing the Literature by Decisions 8, 9, 10, and 11 and Reporting the Results by Decisions 12 and 13

3. Results

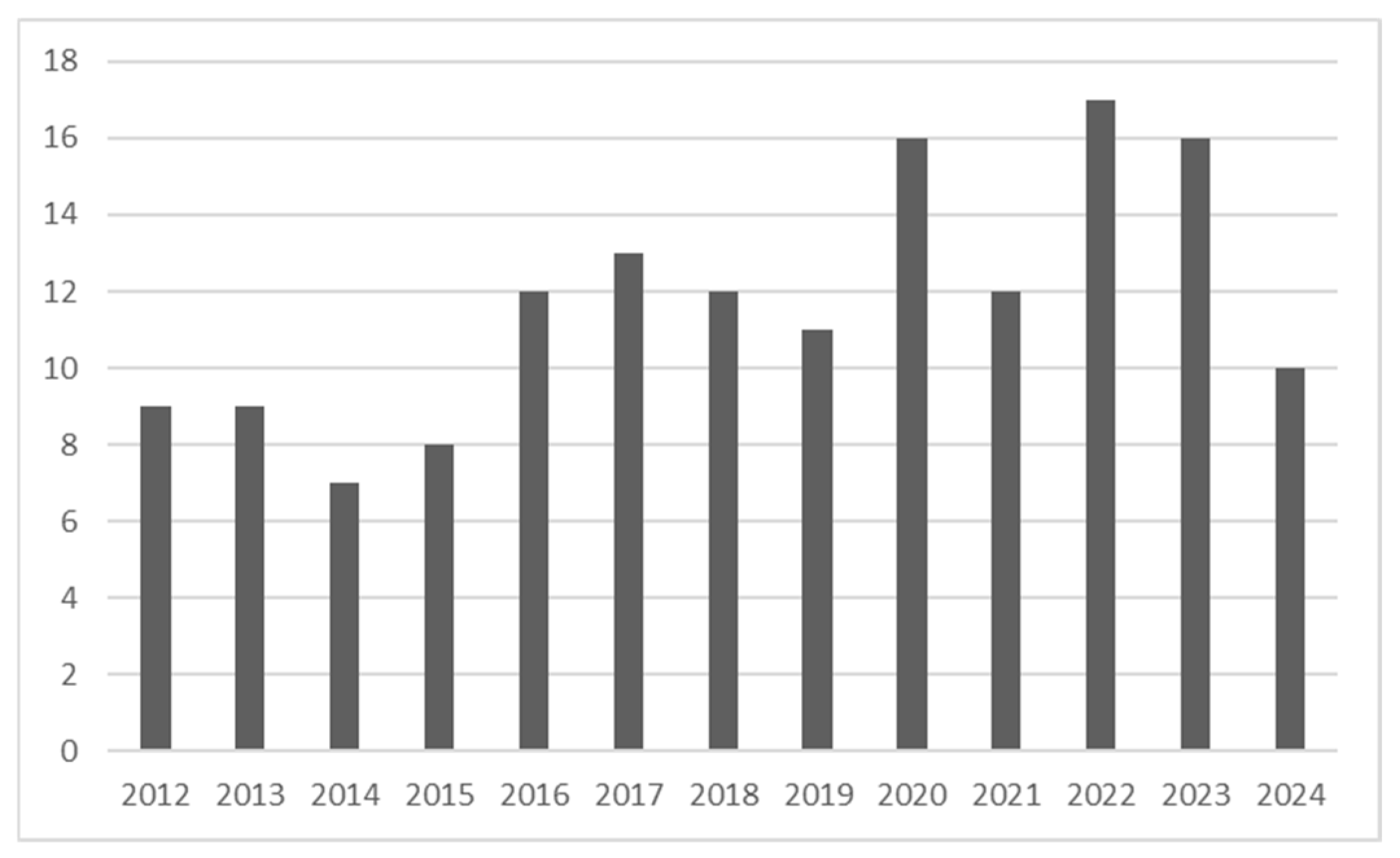

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Frequency Analysis

3.3. Content Analysis

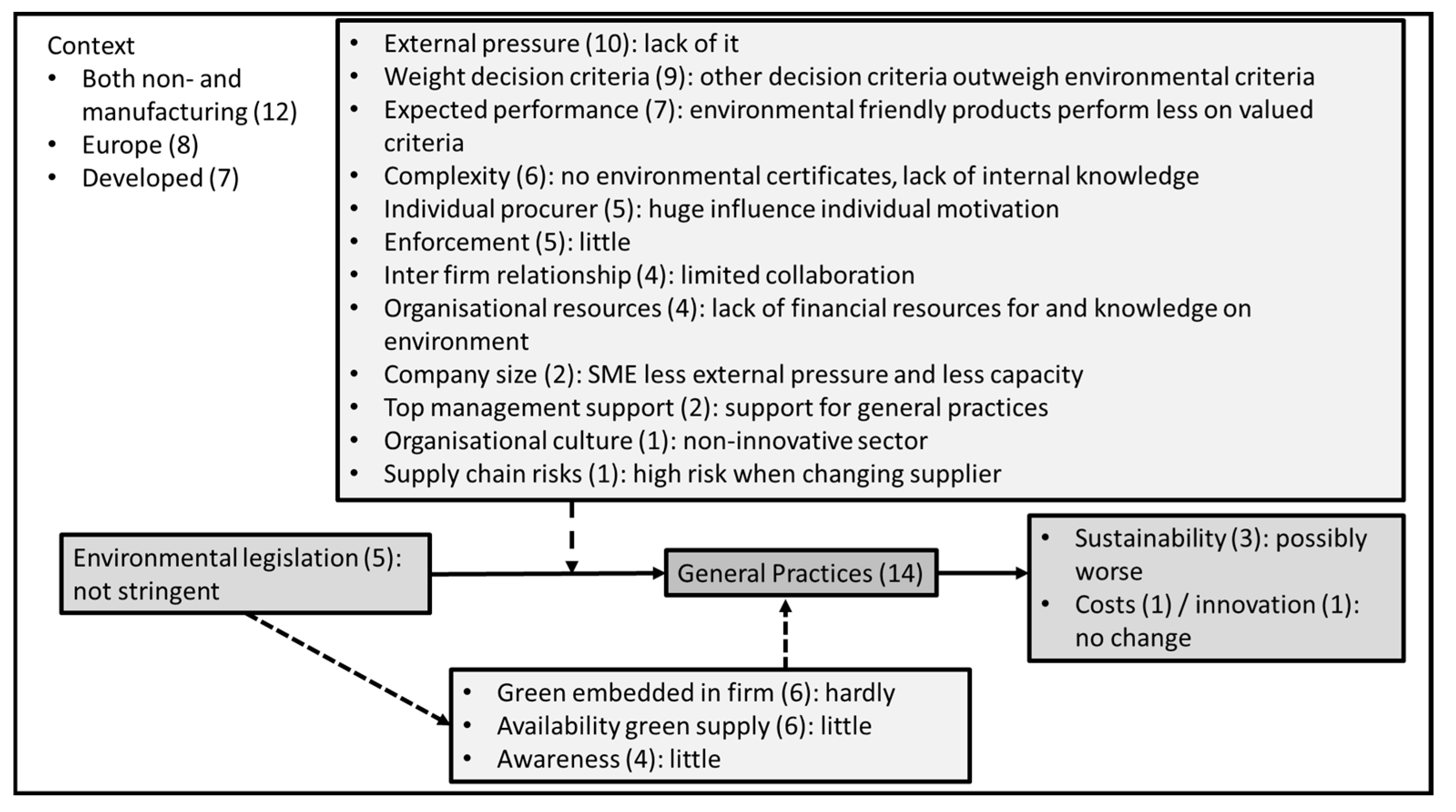

3.3.1. General Practices (GeP)

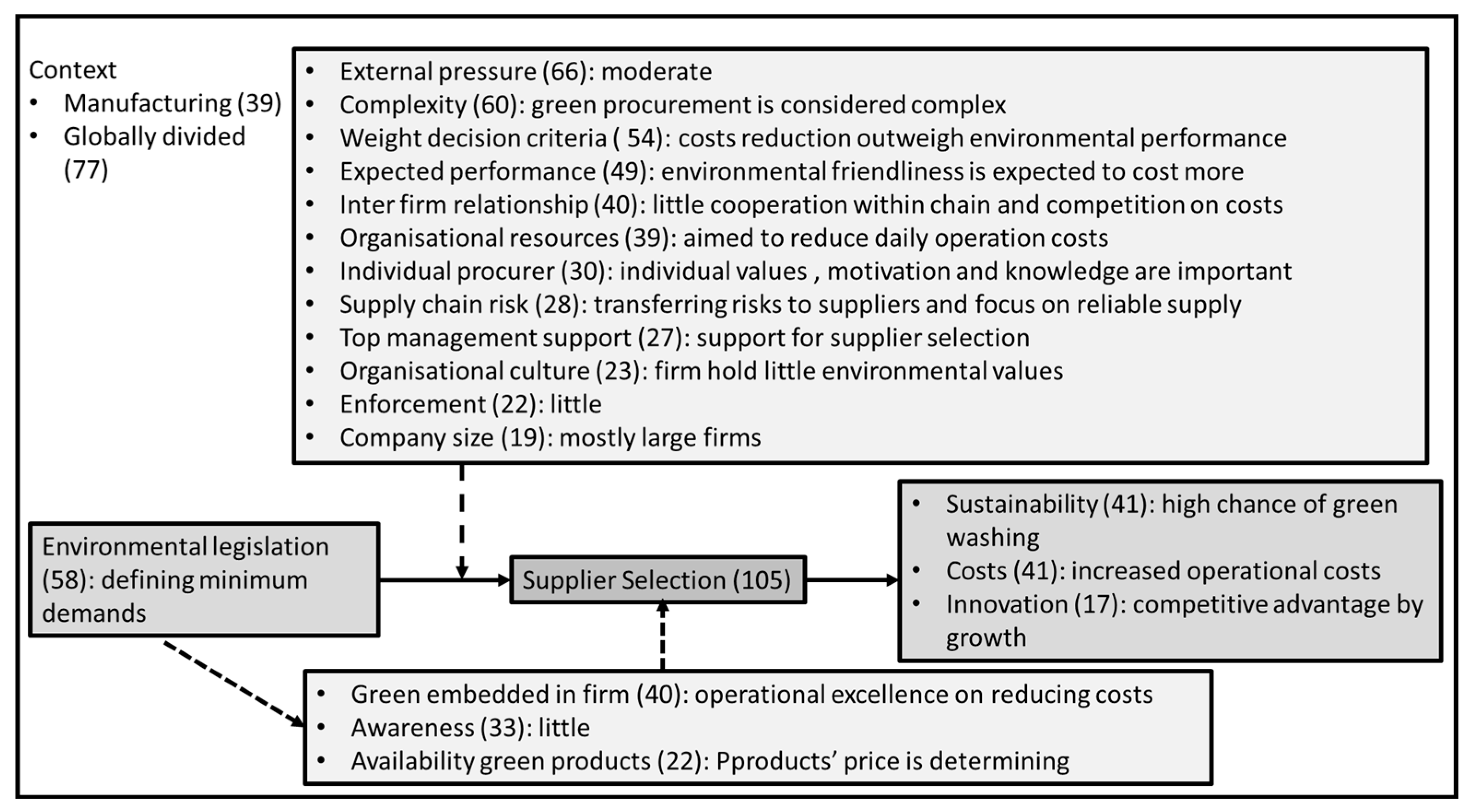

3.3.2. Supplier Selection (SuS)

3.3.3. Supplier Involvement (SuI)

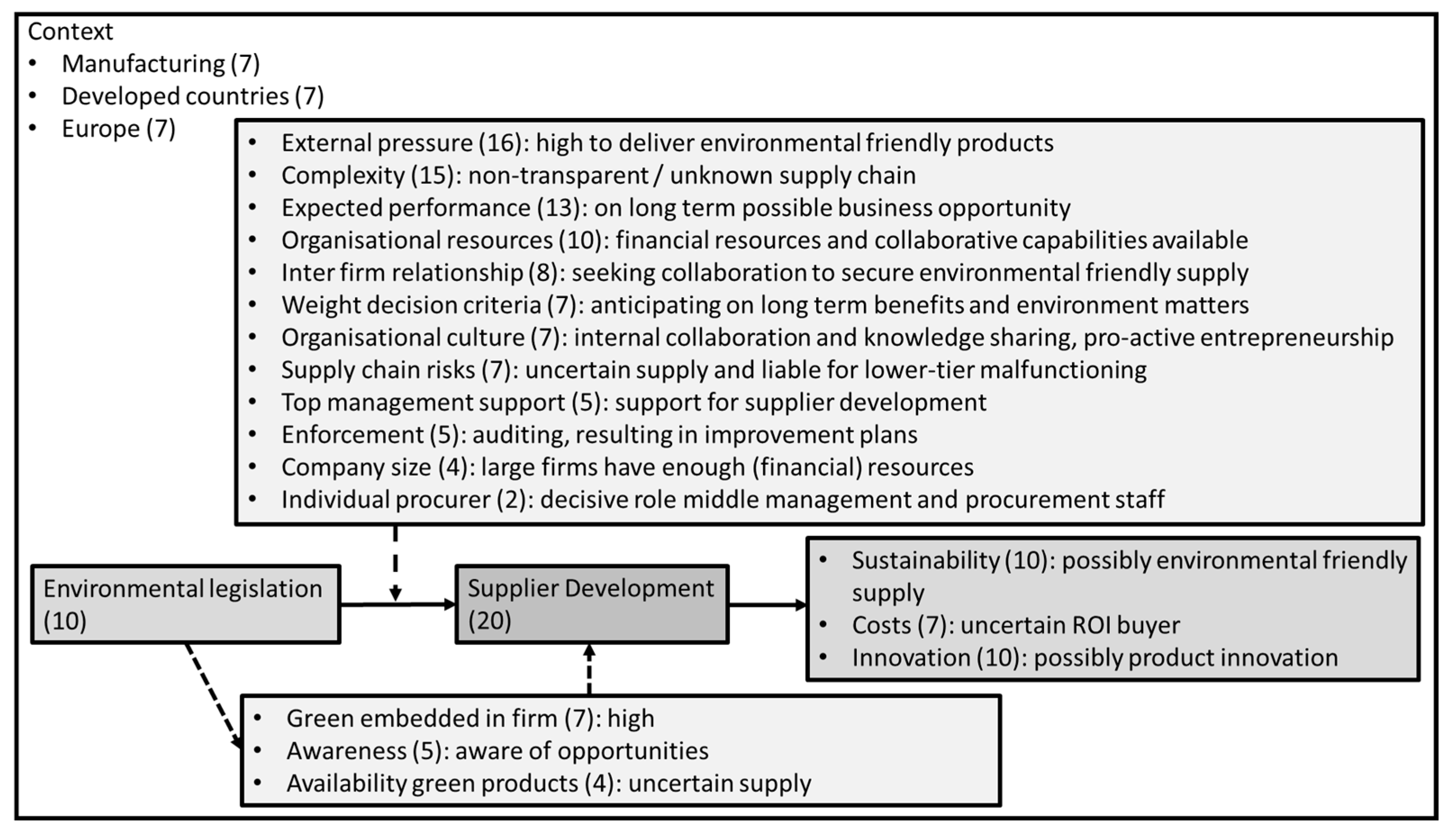

3.3.4. Supplier Development (SuD)

3.3.5. Supplier Performance (SuP)

4. Discussion

4.1. Context

- P1.

- Environmental legislation is effective in countries and sectors with high external pressure to reduce environmental impact.

4.2. Intervention

- P2.

- Triggered by environmental legislation, firms will apply collaborative green procurement if reducing environmental impact will bring or is expected to bring a business opportunity.

4.3. Moderating and Mediating Variables

- P3.

- Effective environmental legislation increases unambiguous external pressure on green procurement.

- P4.

- Effective environmental legislation prices pollution and is enforced by supporting firms to achieve the intended outcome.

- P5.

- Effective environmental legislation is easy to comply to without investments.

- P6.

- Effective environmental legislation brings benefits for the entire global supply chain to achieve the intended outcome.

- P7.

- Effective environmental legislation creates awareness and intrinsic motivations among management and individual procurers to achieve the intended outcome.

4.4. Outcome

- P8.

- Effective environmental legislation strengthens vertical and horizontal collaboration to achieve the intended outcome and business opportunity.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EU | European Union |

| GeP | General practices |

| SuS | Supplier Selection |

| SuI | Supplier Involvement |

| SuD | Supplier Development |

| SuP | Supplier Performance |

Appendix A. General Practices

- Context sector: Man: manufacturing sector; N-ma: non-manufacturing sector; B: both manufacturing and non-manufacturing; N: non-mentioning of sector.

- Context region: Af: Africa; Am: Americas; As: Asia; Eu: Europe; Oc: Oceania; d: developed, u: underdeveloped; e: emerging; GL: countries divided globally; N: non-mentioning of region.

- Legislation: EL: environmental legislation; NIF: environmental legislation not in force; DJA: different jurisdictions apply; NIM: no intervention mentioned.

| Context | Intervention | Mechanism | Mediating Variables | Moderating Variables | Outcome | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Context Sector | Context Region | Legislation | Green Sourcing Strategy | Embedded | Awareness | Availability | Complexity | Ext. Pressure | Org. Resources | SC Risks | Exp. Performance | Weight Criteria | Top Management | Indi. Procurer | Company Size | Enforcement | Org. Culture | Market Relations | Sustainability | Costs | Responsiveness | Security | Resilience | Innovation |

| Abrahams [61] | n-ma | Am-u | Nif | GP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Agrawal and Lee [63] | n | n | nim | GP | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Akhavan and Beckmann [24] | B | GL-e | nif | GP | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Brooks and Rich [133] | Man | Eu-d | nif | GP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Chevallier-Chantepie and Batt [73] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | GP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Chkanikova [17] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | GP | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Jazairy [81] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nif | GP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Large, Kramer [134] | n-ma | Eu-d | El | GP | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mosgaard, Riisgaard [125] | n-ma | Eu-d | El | GP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Seckin and Sen (2018) | man | Eu-e | el | GP | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tate, Ellram [16] | man | N | el | GP | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| van der Werff, Trienekens [23] | man | Eu-d | Nim | GP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Yap, Yu Han [135] | man | As-e | nif | GP | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Ye, Huang [28] | N | GL | El | GP | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 14 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

Appendix B. Supplier Selection

| Context | Intervention | Mechanism | Mediating Variables | Moderating Variables | Outcome | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Context Sector | Context Region | Legislation | Green Sourcing Strategy | Embedded | Awareness | Availability | Complexity | Ext. Pressure | Org. Resources | SC Risks | Exp. Performance | Weight Criteria | Top Management | Indi. Procurer | Company Size | Enforcement | Org. Culture | Market Relations | Sustainability | Costs | Responsiveness | Security | Resilience | Innovation |

| Acquah, Baah [62] | Man | Af-u | El | Ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Adda [46] | Man | Af-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Agrawal and Lee [63] | N | N | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Akhavan and Beckmann [24] | B | EU-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Andersén, Jansson [93] | Man | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Aral, Beil [101] | N | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Atarah, Mustapha [141] | N | Af-e | Nim | Ss | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Barbanti, Anholon [13] | Man | Am-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Beske-Janssen, Johnsen [12] | N | N | El | SS | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bian and Zhao [29] | N-ma | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Bohari, Skitmore [56] | Man | As-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Bonn, Chun [150] | n-ma | Am-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Boruchowitch and Fritz [94] | N | Eu-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Boström and Karlsson [112] | N | Eu-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Brockhaus, Fawcett [49] | n | GL | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Brockhaus, Kersten [138] | B | Am-/ Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Busse, Kach [71] | N | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Candrasa, Cen [50] | Man | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cantor, Morrow [95] | n-ma | GL | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Chen, Ye [113] | man | As-e | nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cherkaoui and Aliat [114] | N | N | Nif | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Cherkaoui and Aliat [72] | n | n | el | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Chevallier-Chantepie and Batt [73] | n-ma | Eu-d | nim | ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Chkanikova [17] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Choi [144] | B | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Choi [143] | B | N | El | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Dai, Lin [137] | man | N | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| de Campos and de Mello [85] | Man | Am-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| de Lima Souza, Gonçalves Tondolo [40] | N | Am-d | Nim | Ss | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ershadi, Jefferies [102] | Man | Oc-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Etse, McMurray [7] | B | Af-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Etse, McMurray [75] | B | Af-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Etse, McMurray [96] | N | Af-e | nim | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fang, Wang [6] | man | As-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Fayezi, Zomorrodi [65] | N | Oc-d | el | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Fleury and Davies [76] | man | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Fontana, Öberg [8] | B | As-u | el | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ghadge, Kidd [66] | N | GL | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ghadimi, Azadnia [14] | man | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Ghosh, Jha [30] | man | n | el | ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Giunipero, Hooker [97] | N | Am-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Goebel, Reuter [86] | N | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Govindan, Kaliyan [77] | man | As-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Harms, Hansen [20] | N | Eu-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Hsu, Hu [67] | B | GL | nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Indrianto, Kusmantini [148] | n-ma | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Islam [123] | man | As-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Ismail, Ali [105] | B | N | nim | ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Jabbour, Frascareli [51] | N | Am-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jiang, Jia [27] | N | N-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Kannan [115] | B | Eu-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Kaur and Singh [145] | man | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Khan and Hinterhuber [87] | B | Gl | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Kozuch, Langen [88] | N | N | el | SS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Kwabena Anin, Ataburo [124] | n | Af-e | nim | SS | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Laari, Töyli [21] | B | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Larson, Rivera-Zuniga [41] | n-ma | Am-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Leppelt, Foerstl [106] | Man | Eu-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Lintukangas, Hallikas [107] | B | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Liu, Liu [117] | Man | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Ma, Ho [78] | Man | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Mariadoss, Chi [38] | B | Am-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Masudin, Umamy [146] | N | N | Nim | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| McMurray, Islam [2] | N | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Mojumder, Singh [119] | Man | As-e | Nif | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Mueller, West [1] | B | Eu/ Am-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Niu, Chen [89] | B | n | el | ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Niu, Zhang [109] | N | As-e | el | ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opoku, Deng [82] | Man | As-e | nif | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Paluš, Slašťanová [140] | man | Eu-d | el | ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Pinto [22] | man | Eu-d | el | ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Ramakrishnan, Haron [129] | Man | As-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Rejeb, Rejeb [57] | n | n | Nim | ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Reuter, Goebel [52] | N | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Richards and Font [120] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Riikkinen, Kauppi [147] | N | Eu-d | Dja | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ruparathna and Hewage [90] | Man | Am-d | Nif | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Sahoo and Jakhar [58] | man | As-e | El | ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Schneider and Wallenburg [39] | N | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Schulze and Bals [126] | N | N | Nim | Ss | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Seckin and Sen (2018) | man | Eu-e | el | ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Shalique, Padhi [139] | n-ma | As-e | nim | ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sharma, Chandna [111] | B | As-e | El | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Shen, Zhang [91] | man | As-e | el | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Shen, Zhang [53] | man | As-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Silva and Nunes [26] | N | N | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Singh and Chan [83] | N | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Song, Yu [142] | N | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sosnowski [15] | N | N | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Sung Tae, So Ra [103] | man | As-d | el | SS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Tate, Ellram [16] | man | N | el | Ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Thorlakson, de Zegher [68] | B | GL | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Toma, Deaconu [54] | B | Eu-e | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Upadhyay, Sheetal [59] | B | As-e | el | SS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Upstill-Goddard, Glass [169] | Man | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| van den Brink, Kleijn [79] | man | Eu-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| van der Werff, Trienekens [23] | man | Eu-d | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Verma [69] | n-ma | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Wang, Morabito [92] | N | Am-d | Nif | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Wilhelm and Villena [3] | man | n | Nif | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Wong, Chan [136] | Man | As-d | El | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Xiao, Wilhelm [4] | man | Am-/ Eu-d | el | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Xu, Lai [100] | N | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Yu, Tao [127] | Man | As-e | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Zarei, Rasti-Barzoki [70] | N | N | Nim | Ss | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 105 | 40 | 33 | 22 | 60 | 66 | 39 | 28 | 49 | 54 | 27 | 30 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 40 | 41 | 41 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 17 | |||

Appendix C. Supplier Involvement

| Context | Intervention | Mechanism | Mediating Variables | Moderating Variables | Outcome | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Context Sector | Context Region | Legislation | Green Sourcing Strategy | Embedded | Awareness | Availability | Complexity | Ext. Pressure | Org. Resources | SC Risks | Exp. Performance | Weight Criteria | Top Management | Indi. Procurer | Company Size | Enforcement | Org. Culture | Market Relations | Sustainability | Costs | Responsiveness | Security | Resilience | Innovation |

| Brewer and Arnette [153] | N | GL | Nim | Si | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Crespin-Mazet and Dontenwill [18] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | Si | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Dai, Montabon [151] | Man | Am-d | Nim | Si | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Jiang, Jia [27] | N | N-d | El | Si | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Tate, Ellram [16] | man | Eu-d | el | si | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Wantao, Chavez [152] | Man | As-e | Nim | Si | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Yee, Shaharudin [110] | man | As-d | El | Si | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Total | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||

Appendix D. Supplier Development

| Context | Intervention | Mechanism | Mediating Variables | Moderating Variables | Outcome | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Context Sector | Context Region | Legislation | Green Sourcing Strategy | Embedded | Awareness | Availability | Complexity | Ext. Pressure | Org. Resources | SC Risks | Exp. Performance | Weight Criteria | Top Management | Indi. Procurer | Company Size | Enforcement | Org. Culture | Market Relations | Sustainability | Costs | Responsiveness | Security | Resilience | Innovation |

| Ağan, Kuzey [47] | Man | Eu-e | Nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Akhavan and Beckmann [24] | man | GL | nim | Sd | X | X | X | x | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Blome, Hollos [84] | B | Eu-d | Nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | x | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Carmagnac, Silva [154] | n | GL | nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | x | X | |||||||||||||||

| Chkanikova [17] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Cole and Aitken [74] | N | N | Nim | Sd | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Crespin-Mazet and Dontenwill [18] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ehrgott, Reimann [122] | N | Am-/ Eu-d | El | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Foerstl, Meinlschmidt [155] | N | N | Nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Ghadimi, Azadnia [14] | man | N | El | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Grimm, Hofstetter [19] | B | Am-/ Eu-d | El | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Harms, Hansen [20] | N | Eu-d | El | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Hayami, Nakamura [156] | Man | As-d | El | Sd | X | X | x | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Meinlschmidt, Schleper [170] | N | N | Nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Mukherjee, Padhi [108] | n-ma | As-e | el | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Silva and Nunes [26] | N | N | Nim | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Sosnowski [15] | N | N | El | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tate et al. (2012 | man | N | el | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Villena [60] | Man | n | el | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | x | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Villena and Gioia [80] | man | GL | El | Sd | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | x | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Total | 20 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 15 | 16 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | |||

Appendix E. Supplier Performance

| Context | Intervention | Mechanism | Mediating Variables | Moderating Variables | Outcome | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Context Sector | Context Region | Legislation | Green Sourcing Strategy | Embedded | Awareness | Availability | Complexity | Ext. Pressure | Org. Resources | SC Risks | Exp. Performance | Weight Criteria | Top Management | Indi. Procurer | Company Size | Enforcement | Org. Culture | Market Relations | Sustainability | Costs | Responsiveness | Security | Resilience | Innovation |

| Ali, Kaur [157] | Man | As-e | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Bag [48] | Man | Af-e | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Boström [160] | n-ma | Eu-d | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Busse [104] | N | N | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Chkanikova [17] | n-ma | Eu-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Eggert and Hartmann [64] | B | Am-d | nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Ferri and Pedrini [149] | N | Eu-d | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Hallikas, Lintukangas [164] | Man | Eu-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Hollos, Blome [163] | N | Eu-d | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Jiang, Jia [27] | N | N-d | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Khan, Kumar [116] | Man | As-e | El | SP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Khan, Yu [165] | Man | As-e | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Kumar and Rahman [158] | Man | As-e | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Laari, Töyli [21] | B | Eu-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Li, Shan [161] | Man | GL | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Li, Jayaraman [167] | Man | As-e | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Luzzini, Brandon-Jones [118] | B | Am, Eu-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Pinto [22] | Man | Eu-d | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Schoenherr, Modi [168] | Man | Am-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| SeÇKİN and ŞEn [25] | Man | Eu-e | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Shou, Shan [121] | Man | GL | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Shou, Shao [166] | Man | GL | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Tate et al. (2012) | man | N | el | sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| van der Werff, Trienekens [23] | Man | Eu-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Viale, Vacher [98] | Man | Eu-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Whitelock [159] | N | N | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Wu and Huang [99] | B | Am-d | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ye, Huang [28] | N | GL | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Yen and Yen [128] | Man | As-d | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Yook, Choi [162] | Man | As-d | Nim | Sp | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Yu, Zhang [55] | Man | As-e | El | Sp | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Total | 31 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 16 | 23 | 19 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 19 | |||

References

- Mueller, C.; West, C.; Bastos Lima, M.G.; Doherty, B. Demand-Side Actors in Agricultural Supply Chain Sustainability: An Assessment of Motivations for Action, Implementation Challenges, and Research Frontiers. World 2023, 4, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, A.J.; Islam, M.M.; Siwar, C.; Fien, J. Sustainable procurement in Malaysian organizations: Practices, barriers and opportunities. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2014, 20, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.; Villena, V.H. Cascading Sustainability in Multi-tier Supply Chains: When Do Chinese Suppliers Adopt Sustainable Procurement? Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 4198–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Wilhelm, M.; Vaart, T.; Donk, D.P. Inside the Buying Firm: Exploring Responses to Paradoxical Tensions in Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2019, 55, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M.; Roehrich, J.K.; Eßig, M.; Harland, C. Driving sustainable supply chain management in the public sectorThe importance of public procurement in the European Union. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wang, B.; Song, W. Analyzing the interrelationships among barriers to green procurement in photovoltaic industry: An integrated method. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etse, D.; McMurray, A.; Muenjohn, N. The Effect of Regulation on Sustainable Procurement: Organisational Leadership and Culture as Mediators. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 177, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, E.; Öberg, C.; Poblete, L. Nominated procurement and the indirect control of nominated sub-suppliers: Evidence from the Sri Lankan apparel supply chain. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 127, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.R.; Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Special Topic Forum on Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Introduction and Reflections on the Role of Purchasing Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydenko, I.; Ehrler, V.; de Ree, D.; Lewis, A.; Tavasszy, L. Towards a global CO2 calculation standard for supply chains: Suggestions for methodological improvements. Transp. Res. Part D 2014, 32, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltho, C.; Elhedhli, S.; Gzara, F. Green supply chain network design: A review focused on policy adoption and emission quantification. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 208, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske-Janssen, P.; Johnsen, T.; Constant, F.; Wieland, A. New competences enhancing Procurement’s contribution to innovation and sustainability. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2023, 29, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbanti, A.M.; Anholon, R.; Rampasso, I.S.; Martins, V.W.B.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W. Sustainable procurement practices in the supplier selection process: An exploratory study in the context of Brazilian manufacturing companies. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Eff. Board Perform. 2022, 22, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi, P.; Azadnia, A.H.; Heavey, C.; Dolgui, A.; Can, B. A review on the buyer-supplier dyad relationships in sustainable procurement context: Past, present and future. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 1443–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, P.C. Green Concepts in the Supply Chain. LogForum 2022, 18, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.L.; Ellram, L.M.; Dooley, K.J. Environmental purchasing and supplier management (EPSM): Theory and practice. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chkanikova, O. Sustainable Purchasing in Food Retailing: Interorganizational Relationship Management to Green Product Supply. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespin-Mazet, F.; Dontenwill, E. Sustainable procurement: Building legitimacy in the supply network. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, J.H.; Hofstetter, J.S.; Sarkis, J. Exploring sub-suppliers’ compliance with corporate sustainability standards. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1971–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, D.; Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. Strategies in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: An Empirical Investigation of Large German Companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laari, S.; Töyli, J.; Ojala, L. Supply chain perspective on competitive strategies and green supply chain management strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. Investigating the Relationship Between Green Supply Chain Purchasing Practices and Firms’ Performance. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2023, 16, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werff, S.; Trienekens, J.; Hagelaar, G.; Pascucci, S. Patterns in sustainable relationships between buyers and suppliers: Evidence from the food and beverage industry. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, R.M.; Beckmann, M. A configuration of sustainable sourcing and supply management strategies. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2017, 23, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SeÇKİN, F.; ŞEn, C.G. Conceptual Framework for Buyer-Supplier Integration Strategies and Their Association to the Supplier Selection Criteria in the Light of Sustainability [Alici-Tedarikçi Entegrasyon Startejileri Için Kavramsal Tasarim Geliştirilmesi Ve Sürdürülebilirlik Çerçevesinde Tedarikçi Seçim Kriterleri Ile Entegrasyon Stratejilerinin Ilişkilendirilmesi]. J. Aeronaut. Space Technol. 2018, 11, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.E.; Nunes, B. Institutional logic for sustainable purchasing and supply management: Concepts, illustrations, and implications for business strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1138–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Jia, F.; Blome, C.; Chen, L. Achieving sustainability in global sourcing: Towards a conceptual framework. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 25, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Huang, G.; Zhan, Y.; Li, Y. Factors Mediating and Moderating the Relationships Between Green Practice and Environmental Performance: Buyer–Supplier Relation and Institutional Context. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Zhao, X. Competitive environmental sourcing strategies in supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 230, 107891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Jha, A.; Sharma, R.R.K. Managing carbon footprint for a sustainable supply chain: A systematic literature review. Mod. Supply Chain Res. Appl. 2020, 2, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R. What works in Evaluation Reasearch? Br. J. Criminol. 1994, 34, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aken, J.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Halman, J. Conducting and publishing design science research: Inaugural essay of the design science department of the Journal of Operations Management. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 47–48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Sutton, A.; Papaioannou, D. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review, 2nd ed.; Steele, M., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S.; Yawar, S.A.; Land, A.; Khalid, R.U.; Sauer, P.C. The application of theory in literature reviews—Illustrated with examples from supply chain management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Kembro, J.; Wieland, A. A New Paradigm for Systematic Literature Reviews in Supply Chain Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, P.C.; Seuring, S. How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: A guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2023, 17, 1899–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariadoss, B.J.; Chi, T.; Tansuhaj, P.; Pomirleanu, N. Influences of Firm Orientations on Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3406–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Wallenburg, C.M. Implementing sustainable sourcing—Does purchasing need to change? J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Souza, J.; Gonçalves Tondolo, V.A.; Portella Tondolo, R.d.R.; Lerch Lunardi, G.; Régio Brambilla, F. Environmental Damage: When Anger Can Lead to Supplier Discontinuity [Daño ambiental: Cuando el enojo puede conducir a la discontinuidad del proveedor]. Rev. Adm. Empres. 2022, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Rivera-Zuniga, J.; Garst, B.A.; Keith, S.; Sudman, D.; Browne, L. “Going Green”: Investigating Environmental Sustainability Practices in Camp Organizations across the United States. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2023, 15, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, L.; Tate, W.; Carnovale, S.; Di Mauro, C.; Bals, L.; Caniato, F.; Gualandris, J.; Johnsen, T.; Matopoulos, A.; Meehan, J.; et al. Future business and the role of purchasing and supply management: Opportunities for ‘business-not-as-usual’ PSM research. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2022, 28, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, S.; Nilashi, M.; Almulihi, A.; Alrizq, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Mohd, S.; Ahmadi, H.; Syed Azhar, S.N.F. Green Supply Chain Management practices and impact on firm performance: The moderating effect of collaborative capability. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Tran, M.D. Environmental collaboration, responsible innovation, and firm performance: The moderating role of stakeholder pressure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, D.; Viale, L.; Ruel, S.; Stek, K. The nexus of stewardship and sustainability in supply chains: Revealing the impact of purchasing social responsibility on innovativeness and operation performance. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2025, 37, 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adda, G. Examining the relationship between procurement strategies and organizational performance of Ghanaian firms: How does strategic procurement drive organizational success? Econ. Manag. Amp; Sustain. 2024, 9, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağan, Y.; Kuzey, C.; Acar, M.F.; Açıkgöz, A. The relationships between corporate social responsibility, environmental supplier development, and firm performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S. Identification of Green Procurement Drivers and Their Interrelationship Using Total Interpretive Structural Modelling. Vision 2017, 21, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, S.; Fawcett, S.E.; Hobbs, S.; Schwarze, A.S. Boldly going where firms have gone before? Understanding the evolution of supplier codes of conduct. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 743–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candrasa, L.; Cen, C.C.; Cahyadi, W.; Cahyadi, L.; Pratama, I. Green Supply Chain, Green Communication and Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from Thailand. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 398–406. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Frascareli, F.C.d.O.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Green supply chain management and firms’ performance: Understanding potential relationships and the role of green sourcing and some other green practices. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, C.; Goebel, P.; Foerstl, K. The impact of stakeholder orientation on sustainability and cost prevalence in supplier selection decisions. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. Key factors affecting green procurement in real estate development: A China study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, S.; Deaconu, A.; Radu, C. Sustainable purchasing role in the development of business. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Business Excellence 2021, Bucharest, Romania, 18–19 March 2021; Volume 15, pp. 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Huo, B. The impact of supply chain quality integration on green supply chain management and environmental performance. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 30, 1110–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohari, A.A.M.; Skitmore, M.; Xia, B.; Teo, M.; Khalil, N. Key stakeholder values in encouraging green orientation of construction procurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Kayikci, Y.; Appolloni, A.; Treiblmaier, H. Mapping the knowledge domain of green procurement: A review and bibliometric analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 30027–30061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Jakhar, S.K. Industry 4.0 deployment for circular economy performance—Understanding the role of green procurement and remanufacturing activities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1144–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.K.; Sheetal; Khan, M.I. Comparing Sustainable Procurement in Green Supply Chain Practices Across Indian Manufacturing and Service Sectors. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2023, 13, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, V.n.H. The Missing Link? The Strategic Role of Procurement in Building Sustainable Supply Networks. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 1149–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, D. The barriers to environmental sustainability in post-disaster settings: A case study of transitional shelter implementation in Haiti. Disasters 2014, 38, S25–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, I.S.K.; Baah, C.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E. Green procurement and green innovation for green organizational legitimacy and access to green finance: The mediating role of total quality management. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2023, 42, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.; Lee, D. The Effect of Sourcing Policies on Suppliers’ Sustainable Practices. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, J.; Hartmann, J. Purchasing’s contribution to supply chain emission reduction. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2021, 27, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayezi, S.; Zomorrodi, M.; Bals, L. Procurement sustainability tensions: An integrative perspective. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 586–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Kidd, E.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Tiwari, M.K. Sustainable procurement performance of large enterprises across supply chain tiers and geographic regions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 764–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.F.; Hu, P.J.H.; Wei, C.P.; Huang, J.W. Green Purchasing by MNC Subsidiaries: The Role of Local Tailoring in the Presence of Institutional Duality. Decis. Sci. 2014, 45, 647–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlakson, T.; de Zegher, J.F.; Lambin, E.F. Companies’ contribution to sustainability through global supply chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.S. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices: Selective Case Studies from Indian Hospitality Industry. Int. Manag. Rev. 2014, 10, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, H.; Rasti-Barzoki, M.; Moon, I. A mechanism design approach to a buyer’s optimal auditing policy to induce responsible sourcing in a supply chain. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 254, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, C.; Kach, A.P.; Bode, C. Sustainability and the False Sense of Legitimacy: How Institutional Distance Augments Risk in Global Supply Chains. J. Bus. Logist. 2016, 37, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkaoui, A.; Aliat, M. Mapping the field of responsible sourcing: Topic modeling through bibliometric analysis. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 6, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier-Chantepie, A.; Batt, P.J. Sustainable Purchasing of Fresh Food by Restaurants and Cafes in France. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.; Aitken, J. The role of intermediaries in establishing a sustainable supply chain. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2020, 26, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etse, D.; McMurray, A.; Muenjohn, N. Sustainable Procurement Practice: The Effect of Procurement Officers’ Perceptions. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 184, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, A.-M.; Davies, B. Sustainable supply chains—Minerals and sustainable development, going beyond the mine. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Kaliyan, M.; Kannan, D.; Haq, A.N. Barriers analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ho, W.; Ji, P.; Talluri, S. Contract Design with Information Asymmetry in a Supply Chain under an Emissions Trading Mechanism. Decis. Sci. 2018, 49, 121–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, S.; Kleijn, R.; Tukker, A.; Huisman, J. Approaches to responsible sourcing in mineral supply chains. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, V.n.H.; Gioia, D.A. On the riskiness of lower-tier suppliers: Managing sustainability in supply networks. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 64, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazairy, A. Aligning the purchase of green logistics practices between shippers and logistics service providers. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2020, 82, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A.; Deng, J.; Elmualim, A.; Ekung, S.; Hussien, A.A.; Buhashima Abdalla, S. Sustainable procurement in construction and the realisation of the sustainable development goal (SDG) 12. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Chan, S.W. The Impact of Electronic Procurement Adoption on Green Procurement towards Sustainable Supply Chain Performance-Evidence from Malaysian ISO Organizations. J. Open Innov. 2022, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, C.; Hollos, D.; Paulraj, A. Green procurement and green supplier development: Antecedents and effects on supplier performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos, J.G.F.; de Mello, A.M. Transaction Costs in Environmental Purchasing: Analysis Through Two Case Studies. J. Oper. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 10, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, P.; Reuter, C.; Pibernik, R.; Sichtmann, C.; Bals, L. Purchasing managers’ willingness to pay for attributes that constitute sustainability. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 62, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Hinterhuber, A. Antecedents and consequences of procurement managers’ willingness to pay for sustainability: A multi-level perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuch, A.; Langen, M.; von Deimling, C.; Eßig, M. Does green procurement pay off? Assessing the practice–performance link employing meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J. Punishing or subsidizing? Regulation analysis of sustainable fashion procurement strategies. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 107, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparathna, R.; Hewage, K. Sustainable procurement in the Canadian construction industry: Challenges and benefits. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 42, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Long, Z. Significant barriers to green procurement in real estate development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 116, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Morabito, M.; Payne, C.T.; Robinson, G.; Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, B.C.A. Identifying institutional barriers and policy implications for sustainable energy technology adoption among large organizations in California. Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersén, J.; Jansson, C.; Ljungkvist, T. Can environmentally oriented CEOs and environmentally friendly suppliers boost the growth of small firms? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruchowitch, F.; Fritz, M.M.C. Who in the firm can create sustainable value and for whom? A single case-study on sustainable procurement and supply chain stakeholders. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, D.E.; Morrow, P.C.; Montabon, F. Engagement in Environmental Behaviors Among Supply Chain Management Employees: An Organizational Support Theoretical Perspective. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 48, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etse, D.; McMurray, A.; Muenjohn, N. Financial capacity and sustainable procurement: The mediating effects of sustainability leadership and socially responsible human resource capability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunipero, L.C.; Hooker, R.E.; Denslow, D. Purchasing and supply management sustainability: Drivers and barriers. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viale, L.; Vacher, S.; Frelet, I. Open innovation as a practice to enhance sustainable supply chain management in SMEs. Supply Chain Forum: Int. J. 2022, 23, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-J.; Huang, P.-C. Business analytics for systematically investigating sustainable food supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Lai, I.K.W.; Tang, H. From corporate environmental responsibility to purchase intention of Chinese buyers: The mediation role of relationship quality. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, K.D.; Beil, D.R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Supplier Sustainability Assessments in Total-Cost Auctions. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 902–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershadi, M.; Jefferies, M.; Davis, P.; Mojtahedi, M. Achieving Sustainable Procurement in Construction Projects: The Pivotal Role of a Project Management Office. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung Tae, K.; So Ra, P.; Hong-Hee, L. The Impact of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Performances of SMEs in the Electronics Industry: A Korean Case. J. Manag. Issues 2023, 35, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, C. Doing Well by Doing Good? The Self-Interest of Buying Firms and Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Ali, A.M.; Abdelhafeez, A.; Ei-Douh, A.A.-R.; Ibrahim, M.; Abdel-aziem, A.H. Neutrosophic Multi-Criteria Decision Making for Sustainable Procurement in Food Business. Neutrosophic Sets Syst. 2023, 57, 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Leppelt, T.; Foerstl, K.; Reuter, C.; Hartmann, E. Sustainability management beyond organizational boundaries–sustainable supplier relationship management in the chemical industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintukangas, K.; Hallikas, J.; Kähkönen, A.K. The Role of Green Supply Management in the Development of Sustainable Supply Chain. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Padhi, S.S.; Jayaram, J. Designing socially optimal rates of tax and rebate structures in directing migration of risk-averse suppliers towards sustainable products. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 6485–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, J. How to Induce Multinational Firms’ Local Sourcing to Break Carbon Lock-in? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 315, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, F.M.; Shaharudin, M.R.; Ma, G.; Mohamad Zailani, S.H.; Kanapathy, K. Green purchasing capabilities and practices towards Firm’s triple bottom line in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Chandna, P.; Bhardwaj, A. Green supply chain management related performance indicators in agro industry: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M.; Karlsson, M. Responsible Procurement, Complex Product Chains and the Integration of Vertical and Horizontal Governance. Environ. Policy Gov. 2013, 23, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-K.; Ye, Y.; Wen, M.-H. Efficiency of metaverse on the improvement of the green procurement policy of semiconductor supply chain—Based on behaviour perspective. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkaoui, A.; Aliat, M. Enablers, Obstacles, and Business Impacts of Responsible Sourcing Practices: A Systematic Literature Review. Gestion 2022, 39, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, D. Sustainable procurement drivers for extended multi-tier context: A multi-theoretical perspective in the Danish supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E 2021, 146, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Kumar, A.; Liu, Y.; Gupta, P.; Sharma, D. Modeling enablers of agile and sustainable sourcing networks in a supply chain: A case of the plastic industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. Uncovering the influence mechanism between top management support and green procurement: The effect of green training. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzini, D.; Brandon-Jones, E.; Brandon-Jones, A.; Spina, G. From sustainability commitment to performance: The role of intra- and inter-firm collaborative capabilities in the upstream supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 165, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojumder, A.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Liu, Y. Mitigating the barriers to green procurement adoption: An exploratory study of the Indian construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.; Font, X. Sustainability in the tour operator—Ground agent supply chain. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Y.; Shan, S.; Chen, A.; Cheng, Y.; Boer, H. Aspirations and environmental performance feedback: A behavioral perspective for green supply chain management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 729–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrgott, M.; Reimann, F.; Kaufmann, L.; Carter, C.R. Environmental Development of Emerging Economy Suppliers: Antecedents and Outcomes. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Murad, M.W.; McMurray, A.J.; Abalala, T.S. Aspects of sustainable procurment practices by public and private organisations in SAudi Arabia: An empirical study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2017, 24, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwabena Anin, E.; Ataburo, H.; Effah Ampong, G.; Osei Bempah, N.D. A resource orchestration perspective of the link between environmental orientation and green purchasing: Empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosgaard, M.; Riisgaard, H.; Huulgaard, R.D. Greening non-product-related procurement—When policy meets reality. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 39, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, H.; Bals, L. Implementing sustainable purchasing and supply management (SPSM): A Delphi study on competences needed by purchasing and supply management (PSM) professionals. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2020, 26, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tao, Y.; Wang, D.; Yang, M.M. Disengaging pro-environmental values in B2B green buying decisions: Evidence from a conjoint experiment. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 105, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.-X.; Yen, S.-Y. Top-management’s role in adopting green purchasing standards in high-tech industrial firms. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, P.; Haron, H.; Yen-Nee, G. Factors Influencing Green Purchasing Adoption for Small and Medium Enterprises (Smes) in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2015, 16, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, S.A.; Davis, E.W.; Spekman, R.E.; Sandor, J. Outcome-Driven Supply Chains. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2010, 51, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, L.; Seuring, S. Linking the digital and sustainable transformation with supply chain practices. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 62, 949–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudusinghe, J.I.; Seuring, S. Supply chain collaboration and sustainability performance in circular economy: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 245, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.; Rich, H. Sustainable construction and socio-technical transitions in London’s mega-projects. Geogr. J. 2016, 182, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, R.O.; Kramer, N.; Hartmann, R.K. Procurement of logistics services and sustainable development in Europe: Fields of activity and empirical results. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Yu Han, T.E.H.; Siaw Chuing, L.O.O.; Shavarebi, K.; Zamharira, B.S. Green Procurement in the Construction Industry: Unfolding New Underlying Barriers for a Developing Country Context. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2024, 30, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.W.; Chan, J.K.S.; Wadu, M.J. Facilitating effective green procurement in construction projects: An empirical study of the enablers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Lin, Y.-T.; Shi, R.; Xu, D. A manufacturer’s responsible sourcing strategy: Going organic or participating in fair trade? Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 291, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, S.; Kersten, W.; Knemeyer, A.M. Where Do We Go From Here? Progressing Sustainability Implementation Efforts Across Supply Chains. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalique, M.S.; Padhi, S.S.; Jayaram, J.; Pati, R.K. Adoption of symbolic versus substantive sustainability practices by lower-tier suppliers: A behavioural view. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 4817–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluš, H.; Slašťanová, N.; Parobek, J.; Čerešňa, R. Proposal of a Model for the Implemantation of Environmentally Sustainable Purchasing in Wood Processing Industry. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen 2023, 65, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atarah, B.A.; Mustapha, A.R.; Nyaaba, P.; Damoah, O.B.O. Sustainable procurement practices and female entrepreneurs: Insights from a developing country. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yu, K.; Zhang, S. Green procurement, stakeholder satisfaction and operational performance. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 1054–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.-M. Local sourcing and fashion quick response system: The impacts of carbon footprint tax. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2013, 55, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.-M. Carbon footprint tax on fashion supply chain systems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 68, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Singh, S.P. Sustainable procurement and logistics for disaster resilient supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 309–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masudin, I.; Umamy, S.Z.; Al-Imron, C.N.; Restuputri, D.P. Green procurement implementation through supplier selection: A bibliometric review. Cogent Eng. 2022, 9, 2119686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikkinen, R.; Kauppi, K.; Salmi, A. Learning Sustainability? Absorptive capacities as drivers of sustainability in MNCs’ purchasing. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrianto, A.P.; Kusmantini, T.; Sugandini, D. Green Capabilities Mediate the Effect of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Farmers Business Performance and Vegetable Non-Pesticide (Study on “Lestari” Women Farmer Group in Bantul Regency). Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 27, 639–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, L.M.; Pedrini, M. Socially and environmentally responsible purchasing: Comparing the impacts on buying firm’s financial performance, competitiveness and risk. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, M.A.; Chun, Y.; Yoo, J.J.-E.; Cho, M. Green Purchasing by Wine Retailers: Roles of Individual Values, Competences and Organizational Culture. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 62, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Montabon, F.L.; Cantor, D.E. Reprint of “Linking rival and stakeholder pressure to green supply management: Mediating role of top management support”. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 74, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantao, Y.; Chavez, R.; Mengying, F. Green supply management and performance: A resource-based view. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, B.; Arnette, A.N. Design for procurement: What procurement driven design initiatives result in environmental and economic performance improvement? J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2017, 23, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmagnac, L.; Silva, M.E.; Fritz, M.M.C. Exploring sustainable development goals adoption in supply chain management: A typology of coexisting institutional logics. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 3463–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerstl, K.; Meinlschmidt, J.; Busse, C. It’s a match! Choosing information processing mechanisms to address sustainability-related uncertainty in sustainable supply management. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2018, 24, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, H.; Nakamura, M.; Nakamura, A.O. Economic performance and supply chains: The impact of upstream firms׳ waste output on downstream firms׳ performance in Japan. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Kaur, R.; Persis, D.J.; Saha, R.; Pattusamy, M.; Sreedharan, V.R. Developing a hybrid evaluation approach for the low carbon performance on sustainable manufacturing environment. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 324, 249–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Rahman, Z. Buyer supplier relationship and supply chain sustainability: Empirical study of Indian automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, V.G. Multidimensional environmental social governance sustainability framework: Integration, using a purchasing, operations, and supply chain management context. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M. Between Monitoring and Trust: Commitment to Extended Upstream Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shan, S.; Shou, Y.; Kang, M.; Park, Y.W. Sustainable sourcing and agility performance: The moderating effects of organizational ambidexterity and supply chain disruption. Aust. J. Manag. 2022, 48, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, K.H.; Choi, J.H.; Suresh, N.C. Linking green purchasing capabilities to environmental and economic performance: The moderating role of firm size. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2018, 24, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollos, D.; Blome, C.; Foerstl, K. Does sustainable supplier co-operation affect performance? Examining implications for the triple bottom line. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallikas, J.; Lintukangas, K.; Kähkönen, A.-K. The effects of sustainability practices on the performance of risk management and purchasing. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Yu, Z.; Farooq, K. Green capabilities, green purchasing, and triple bottom line performance: Leading toward environmental sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2022–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Y.; Shao, J.; Lai, K.-h.; Kang, M.; Park, Y. The impact of sustainability and operations orientations on sustainable supply management and the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jayaraman, V.; Paulraj, A.; Shang, K.-c. Proactive environmental strategies and performance: Role of green supply chain processes and green product design in the Chinese high-tech industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 2136–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Modi, S.B.; Talluri, S.; Hult, G.T.M. Antecedents and Performance Outcomes of Strategic Environmental Sourcing: An Investigation of Resource-Based Process and Contingency Effects. J. Bus. Logist. 2014, 35, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upstill-Goddard, J.; Glass, J.; Dainty, A.; Nicholson, I. Implementing sustainability in small and medium-sized construction firms. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2016, 23, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinlschmidt, J.; Schleper, M.C.; Foerstl, K. Tackling the sustainability iceberg. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 1888–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thesaurus | Sustainable Procurement |

|---|---|

| OR | |

| Subject OR keyword | sustainable procurement OR sustainable purchasing OR sustainable sourcing OR sustainable buying OR sustainable supply management OR green procurement OR green purchasing OR green sourcing OR green buying OR green supply management OR environmental procurement OR environmental purchasing OR environmental sourcing OR environmental buying OR environmental supply management |

| OR | |

| Subject OR keyword | sustainability AND (procurement OR purchasing OR sourcing OR buying OR supply management) |

| Green Procurement Strategy | Description from Tate | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| General Practices (GeP) | Practices that suggest concern for environmental issues but lack specificity as to what actions are actually being taken |

|

| Supplier Selection (SuS) | Modifying supplier selection criteria in order to incorporate environmental criteria |

|

| Supplier Involvement (SuI) | Captures practices in which a supplier is mentioned as being involved in helping the buying firm improve its own environmental practices |

|

| Supplier Development (SuD) | Captures practices in which the buyer provides support to the supplier in order the help the supplier improve its environmental performance |

|

| Supplier Performance (SuP) | The buying firm’s performance on key sustainability metrics is linked directly to supplier sustainability outcomes |

|

| Mediating Variable | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Green embedded in firm | The procurement department and its strategy are part of an organization and usually follow the corporate strategy. If the firm already defined environmental targets for the entire firm, procurement likely follows. | [22,26,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] |

| Awareness | Awareness of green procurement’s importance may change behaviour and implement green procurement. | [29,56,57,58,59,60] |

| Availability green products | The presence of environmentally friendly products to procure influences green procurement’s possibilities. | [17,48,61] |

| Moderating variable | ||

| External pressure | External pressure drives firms to a certain strategy. However, these pressures are ambiguous due to variating interests and legitimate behaviours. Visible firms are highly influenced by consumers. These firms are close to end-consumers and large, limited liability companies acting globally. | [16,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] |

| Complexity | Green procurement is more complex than conventional procurement. The versatility of “environmentally friendly” complicates defining it and calculating the trade-off between economic and environmental performances. Next, life-cycle accounting, registering environmental impact over a product’s life-spam, is needed. Current long and dynamic supply chains with many unknown lower-tier suppliers complicates this accounting. Lastly, supplier’s environmental performance needs to be monitored continuously. | [1,14,19,20,25,61,65,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] |

| Weight supplier selection criteria | Firms often use several supplier selection criteria. Environmental supplier selection criteria being valued as equally important as economic ones sti-mulates green procurement. | [8,41,81,82,83] |

| Expected performance | If the environmentally friendly products are expected to perform worse on valued supplier selection criteria or if the firm’s performance is expected to worsen due to green procurement, then the procurer is less likely to procure environmentally friendly products. Green procurement is expected to increase operational costs, like procurement costs, administrative costs, and monitoring costs. It is also expected to improve reputation and by this may bring competitive advantage. | [13,24,75,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] |

| Organizational resources | Implementing green procurement requires investments. Enough demand for environmentally friendly products justifies these investments, but firms need enough initial financial resources. Other resources such as knowledge and innovative and collaborative skills are needed for green procurement. | [13,50,72,76,82,83,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100] |

| Inter-firm relationship | The inter-firm relations within a supply chain must enable collaboration and by this collaborative green procurement. | [6,29,48,70,88,98,100,101,102,103] |

| Supply chain risks | Supply chain risks of environmentally friendly products influence the decision for green procurement. | [1,12,19,104,105,106,107,108,109,110] |

| Top management support | Firm’s activities, including green procurement, take place in line with (top) management’s support. | [95,111] |

| Organizational culture | Organizational culture influences organizational decisions. Culture which supports green procurement is characterized by concern for the environment, open for innovation, proactive attitude, flexibility, employee autonomy, trust, knowledge sharing, teamwork, concern for individual values, and creating a win-win situation. Suppliers having the same values facilitate close collaboration. Slow adaptors of innovative concepts, or firms characterized by obedience and a non-collaborative attitude, have little support green procurement. | [7,15,18,22,23,24,25,26,27,48,58,60,61,77,82,86,87,98,105,106,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121] |

| Individual procurer | Middle management’s and individual procurers’ motivation, knowledge, capacity, and attitude towards the environment influence daily operation and by this the effectiveness of green procurement. | [40,41,52,98,120,122,123,124,125,126,127] |

| Enforcement | Enforcement of environmental legislation affects green procurement. | [2,7,21,24,128] |

| Company size | Large firms’ organizational resources enable green procurement. | [54,129] |

| Variable from Framework | Total | GeP | SuS | SuI | SuD | SuP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 152 | N = 14 | N = 105 | N = 7 | N = 20 | N = 31 | ||

| Context | |||||||

| Sector | Manufacturing | 62 | 5 | 39 | 4 | 7 | 19 |

| Both manufacturing and non-manufacturing | 27 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Non-manufacturing | 16 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Unknown sector | 47 | 2 | 36 | 2 | 8 | 6 | |

| Region | Asia | 41 | 1 | 27 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Europe | 39 | 8 | 25 | 2 | 7 | 11 | |

| America’s | 21 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Other | 23 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Unknown region | 34 | 2 | 28 | 1 | 8 | 4 | |

| Developed status | Developed country | 56 | 7 | 36 | 5 | 7 | 16 |

| Non-developed country | 50 | 4 | 36 | 1 | 2 | 8 | |

| Unknown status | 46 | 3 | 33 | 1 | 11 | 7 | |

| Intervention | |||||||

| Environmental legislation in force | 79 | 5 | 58 | 3 | 10 | 16 | |

| Environmental legislation not in force | 11 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mediating variable | |||||||

| Green embedded in firm | 64 | 6 | 40 | 3 | 7 | 16 | |

| Awareness | 46 | 4 | 33 | 1 | 5 | 4 | |

| Availability green products | 29 | 6 | 22 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Moderating variable | |||||||

| External pressure | 94 | 10 | 66 | 5 | 16 | 16 | |

| Complexity | 83 | 6 | 60 | 6 | 15 | 14 | |

| Weight decision criteria | 77 | 9 | 54 | 2 | 7 | 11 | |

| Expected performance | 75 | 7 | 49 | 3 | 13 | 10 | |

| Organizational resources | 62 | 4 | 39 | 6 | 10 | 12 | |

| Inter-firm relationship | 57 | 4 | 40 | 2 | 8 | 16 | |

| Supply chain risks | 41 | 1 | 28 | 2 | 7 | 6 | |

| Top management support | 41 | 2 | 27 | 2 | 5 | 8 | |

| Organizational culture | 41 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 7 | 11 | |

| Individual procurer | 37 | 5 | 30 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Enforcement | 34 | 5 | 22 | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Company size | 30 | 2 | 19 | 2 | 4 | 5 | |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Sustainability | 75 | 3 | 41 | 4 | 10 | 23 | |

| Cost | 64 | 1 | 41 | 4 | 7 | 19 | |

| Innovation | 44 | 1 | 17 | 2 | 10 | 19 | |

| Green Procurement Strategy | Context | Environmental Legislation | Three Most Determining Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier Performance | Manufacturing firms in developed Asian and European countries | Legislation in force |

|

| Supplier Development | Manufacturing firms in developed European countries | Legislation in force |

|

| Supplier Involvement | Manufacturing firms in developed countries | Legislation in force |

|

| Supplier Selection | Manufacturing firms globally divided | Legislation set minimum demands |

|

| General practices | Diverse firms in developed European countries | Lacking legislation |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vocks, L.; Verboeket, V.; Vos, B. The Effects of Environmental Legislation via Green Procurement Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics 2025, 9, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030095

Vocks L, Verboeket V, Vos B. The Effects of Environmental Legislation via Green Procurement Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics. 2025; 9(3):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030095

Chicago/Turabian StyleVocks, Lonneke, Victor Verboeket, and Bart Vos. 2025. "The Effects of Environmental Legislation via Green Procurement Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review" Logistics 9, no. 3: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030095

APA StyleVocks, L., Verboeket, V., & Vos, B. (2025). The Effects of Environmental Legislation via Green Procurement Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics, 9(3), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030095