The Meaning of Emoji to Describe Food Experiences in Pre-Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

), crying face

), crying face  , face with open mouth

, face with open mouth  , neutral face

, neutral face  and face with tears of joy

and face with tears of joy  that were associated with a unique emotional meaning indicating respectively “anger,” “sadness,” “surprise,” “neutral” and “joy.” Interpretations of other emoji were found to depend on age or gender.

that were associated with a unique emotional meaning indicating respectively “anger,” “sadness,” “surprise,” “neutral” and “joy.” Interpretations of other emoji were found to depend on age or gender.2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Selection of Emoji

2.4. Procedures

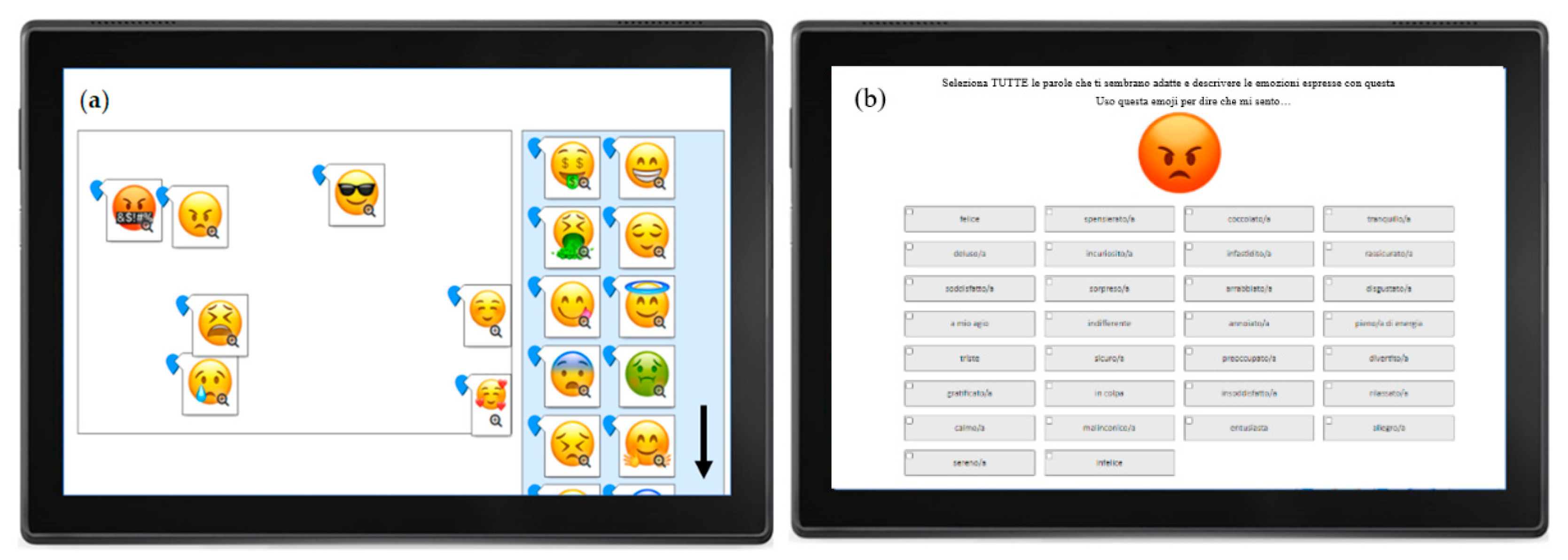

2.4.1. Study 1—Projective Mapping

2.4.2. Study 2—Check-All-That-Apply (CATA)

Selection of Emotion Words

2.4.3. Emotion Usage Questionnaire (EUQ) and Test Evaluation

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Emoji Usage Questionnaire (EUQ)

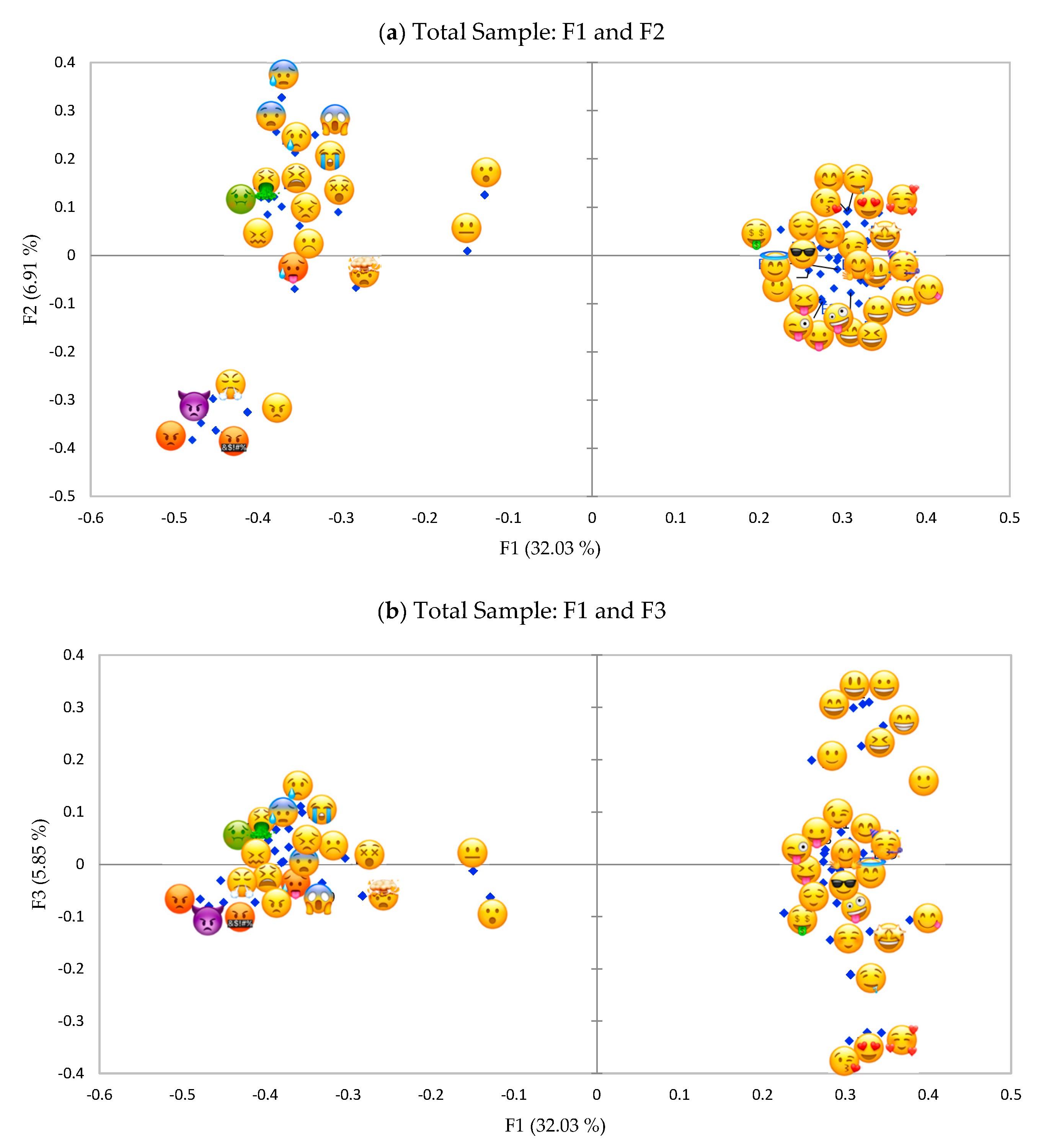

3.2. Study 1—Projective Mapping

and

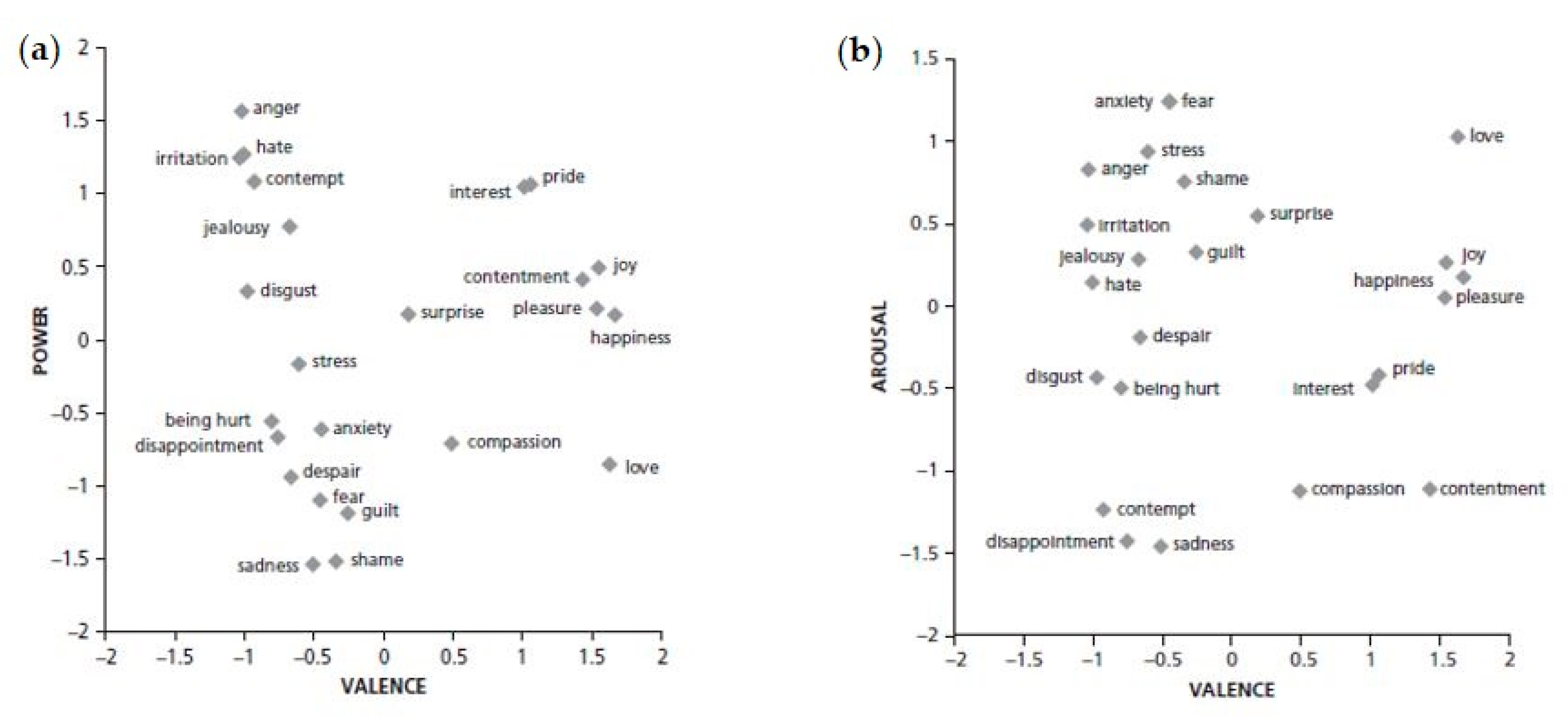

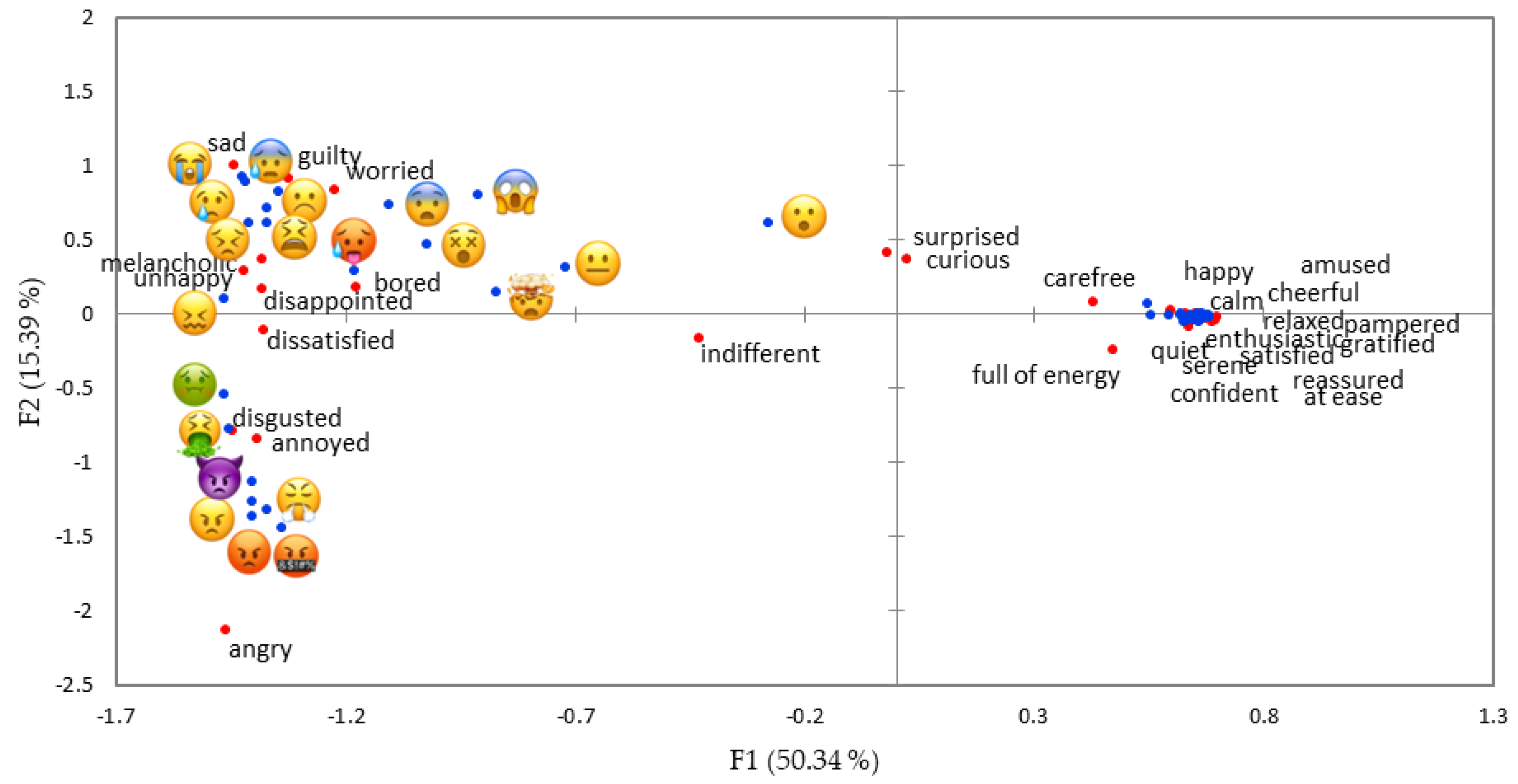

and  , usually recognized as indicating “indifference” and “surprise” which are respectively low and high in arousal [19,20] but both neutral in the valence and power dimension [25], had an intermediate position in Figure 3a even if they were perceived as more similar to the negative emoji group (left side of Figure 3a).

, usually recognized as indicating “indifference” and “surprise” which are respectively low and high in arousal [19,20] but both neutral in the valence and power dimension [25], had an intermediate position in Figure 3a even if they were perceived as more similar to the negative emoji group (left side of Figure 3a). and

and  ) described in the literature as expressing “anger,” characterized by negative valence and high arousal [19,20]. The emotion “anger” is also high in the power dimension [25]. This group is opposed along the second dimension to a group of emoji (including

) described in the literature as expressing “anger,” characterized by negative valence and high arousal [19,20]. The emotion “anger” is also high in the power dimension [25]. This group is opposed along the second dimension to a group of emoji (including  and

and  ), that were described in previous studies on adults [18,19,20] as indicating high to low arousal states and expressing different negative emotions which included “fear” and “sadness.” These emotions, while differing in arousal are both characterized by a low power [25].

), that were described in previous studies on adults [18,19,20] as indicating high to low arousal states and expressing different negative emotions which included “fear” and “sadness.” These emotions, while differing in arousal are both characterized by a low power [25]. and

and  ) that previous studies on adults indicated as expressing “naughty/playful/goofy/mischievous” and “happy,” from other emoji on the top right side of Figure 3a (e.g.,

) that previous studies on adults indicated as expressing “naughty/playful/goofy/mischievous” and “happy,” from other emoji on the top right side of Figure 3a (e.g.,  ) which were found to express “love” [18,19]. These two groups of emoji were all high in arousal, while they differed in power, being the former higher and the latter lower in power [25].

) which were found to express “love” [18,19]. These two groups of emoji were all high in arousal, while they differed in power, being the former higher and the latter lower in power [25]. ) and the ones expressing “love” (

) and the ones expressing “love” ( ) based on previous study with adults [18,19], which are respectively characterized by lower and higher arousal. On the bottom left side of Figure 3b, in addition emoji indicating “anger” and “fear,” both higher in arousal but different in power, are now close to each other. These results taken together suggest that the second dimension can be interpreted as power, while the third dimension could be interpreted as arousal.

) based on previous study with adults [18,19], which are respectively characterized by lower and higher arousal. On the bottom left side of Figure 3b, in addition emoji indicating “anger” and “fear,” both higher in arousal but different in power, are now close to each other. These results taken together suggest that the second dimension can be interpreted as power, while the third dimension could be interpreted as arousal.3.3. Gender- and Age Differences

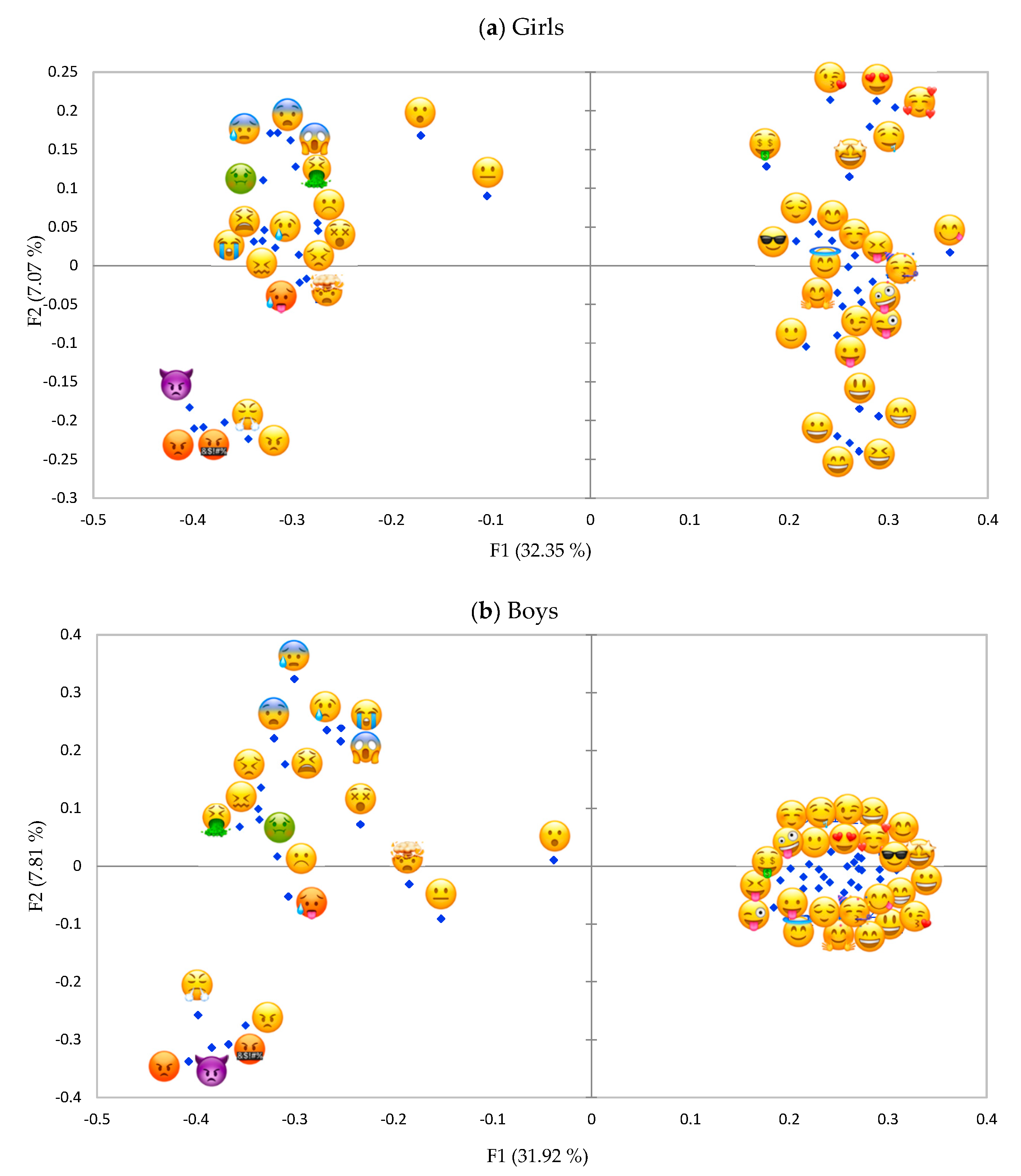

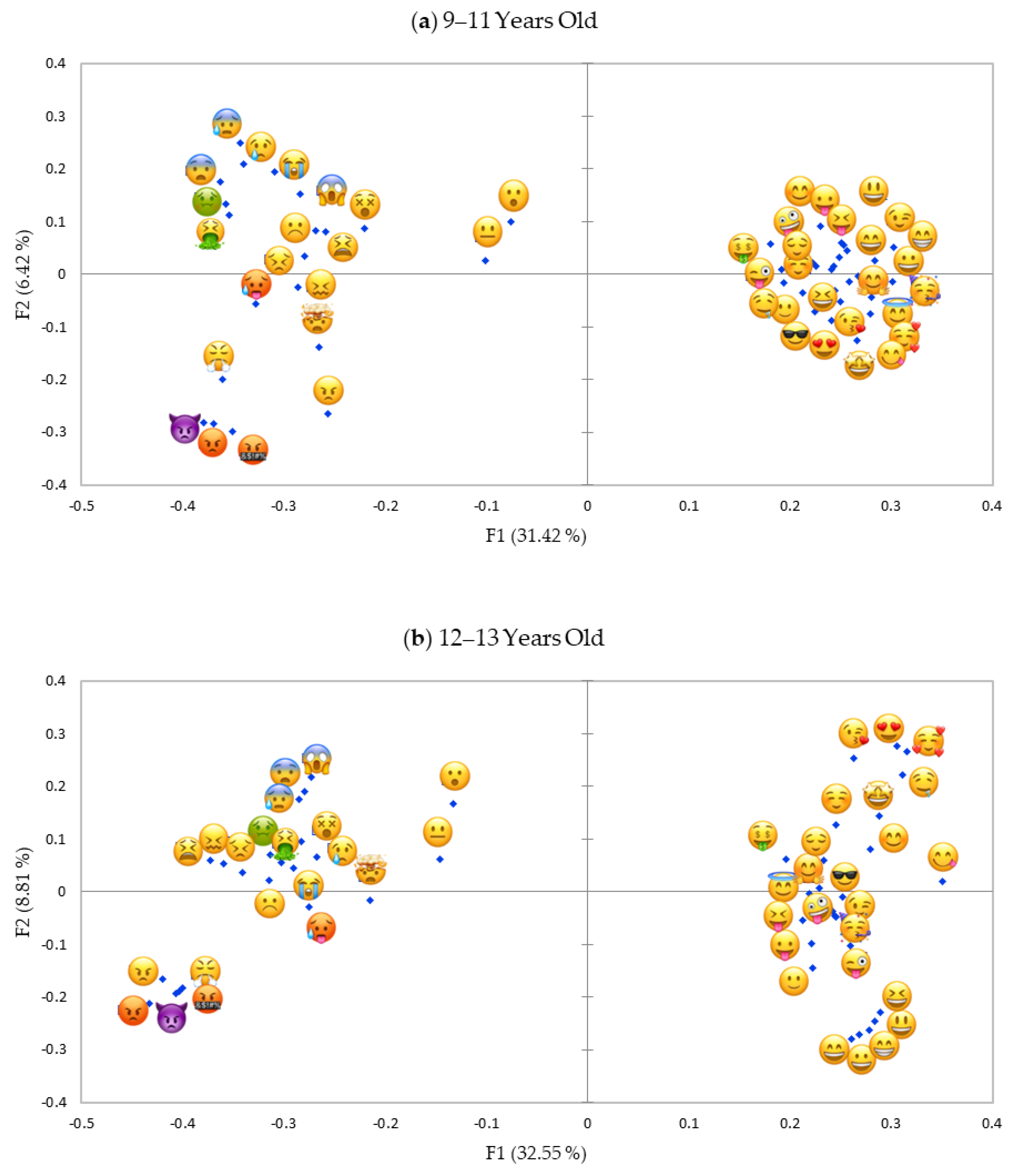

) and some emoji indicating “happy” and thus that were higher in power (e.g.,

) and some emoji indicating “happy” and thus that were higher in power (e.g.,  ). For boys and younger pre-adolescents (9–11 y.o.) this discrimination among positive emoji could not be observed. The emoji face with open mouth

). For boys and younger pre-adolescents (9–11 y.o.) this discrimination among positive emoji could not be observed. The emoji face with open mouth  was interpreted as quite neutral by boys, while it was perceived as more similar to negative emoji by girls. On the other hand, the emoji neutral face

was interpreted as quite neutral by boys, while it was perceived as more similar to negative emoji by girls. On the other hand, the emoji neutral face  had a more negative meaning for boys as demonstrated by the fact that the emoji was closer (= more similar) to the negative emoji in boys than in girls.

had a more negative meaning for boys as demonstrated by the fact that the emoji was closer (= more similar) to the negative emoji in boys than in girls.3.4. Study 2—CATA with Emoji

and

and  that were described by the lowest number of words (5.47 and 5.51, respectively) and the emoji

that were described by the lowest number of words (5.47 and 5.51, respectively) and the emoji  and

and  that were described by the highest number of words (17.20 and 17.83, respectively). Furthermore, on average the number of emotion words selected was higher for positive emoji than for negative emoji (14.29 and 8.67, respectively).

that were described by the highest number of words (17.20 and 17.83, respectively). Furthermore, on average the number of emotion words selected was higher for positive emoji than for negative emoji (14.29 and 8.67, respectively). and

and  ), where 74–95% of pre-adolescents agreed on the emotion word “angry,” and for the last three also on the emotion word “annoyed.” The nauseated face

), where 74–95% of pre-adolescents agreed on the emotion word “angry,” and for the last three also on the emotion word “annoyed.” The nauseated face  (87% of respondents) and the face vomiting

(87% of respondents) and the face vomiting  (84% of respondents) were mostly associated with “disgusted.” The face vomiting

(84% of respondents) were mostly associated with “disgusted.” The face vomiting  was also described by its physical appearances such as “vomiting” and by a “sick” feeling (12% respondents of open-ended response, respectively).

was also described by its physical appearances such as “vomiting” and by a “sick” feeling (12% respondents of open-ended response, respectively). ) was shown to have multiple meaning. All express “unhappy” (49–66%) and “disappointed” (39–47%) while the first two indicated also with large agreement “sad” (75% and 86%, respectively). The last two expressed also “guilty” (40% and 47% respectively). The face screaming fear

) was shown to have multiple meaning. All express “unhappy” (49–66%) and “disappointed” (39–47%) while the first two indicated also with large agreement “sad” (75% and 86%, respectively). The last two expressed also “guilty” (40% and 47% respectively). The face screaming fear  was mainly described by “surprised” (58%) and “worried” (48%) but an additional 22% of pre-adolescents described the emoji as “scared/frightened” in the open comments (“fear” was not included in the emotion list). The fearful face

was mainly described by “surprised” (58%) and “worried” (48%) but an additional 22% of pre-adolescents described the emoji as “scared/frightened” in the open comments (“fear” was not included in the emotion list). The fearful face  was described as “worried” (56%) and “surprised” (42%).

was described as “worried” (56%) and “surprised” (42%). was mainly associated with “indifferent” (58% of respondents) and the face with open mouth

was mainly associated with “indifferent” (58% of respondents) and the face with open mouth  with “surprised” (73% of respondents). The dizzy face

with “surprised” (73% of respondents). The dizzy face  was associated both with surprised (40%) and with worried (40%), suggesting a more negative meaning.

was associated both with surprised (40%) and with worried (40%), suggesting a more negative meaning. and

and  were not clearly associated with any emotion word (each emotion word was checked by less than 40% of the participants). All other emoji were associated with “happy” (33-78%) and many of them also with “cheerful” with large agreement. The emoji

were not clearly associated with any emotion word (each emotion word was checked by less than 40% of the participants). All other emoji were associated with “happy” (33-78%) and many of them also with “cheerful” with large agreement. The emoji  expressed in addition “confident” and “at ease” (50 and 44%, respectively). The emoji

expressed in addition “confident” and “at ease” (50 and 44%, respectively). The emoji  were also associated with “calm” (44–47%) and “serene” (47–60%). The emoji

were also associated with “calm” (44–47%) and “serene” (47–60%). The emoji  were associated with “serene” (44–55%) and “cheerful” (42–71%), while the emoji

were associated with “serene” (44–55%) and “cheerful” (42–71%), while the emoji  and

and  were associated mostly with serene (49 and 36%, respectively). The emoji

were associated mostly with serene (49 and 36%, respectively). The emoji  and

and  expressed a combination of “happy” (70 and 64%), “cheerful” (70 and 49%), “enthusiastic” (49 and 48%), “energetic” (52 and 54%), “amused” (49–42%). The emoji

expressed a combination of “happy” (70 and 64%), “cheerful” (70 and 49%), “enthusiastic” (49 and 48%), “energetic” (52 and 54%), “amused” (49–42%). The emoji  ,

,  ,

,  expressed a combination of “happy” (59–63%), “amused” (51–53%), “cheerful” (57–59%) and “energetic“ (41–57%). Emoji

expressed a combination of “happy” (59–63%), “amused” (51–53%), “cheerful” (57–59%) and “energetic“ (41–57%). Emoji  and

and  were used also to express “in love” based on the further comments provided by the participants (63%, 35% and 17%, respectively).

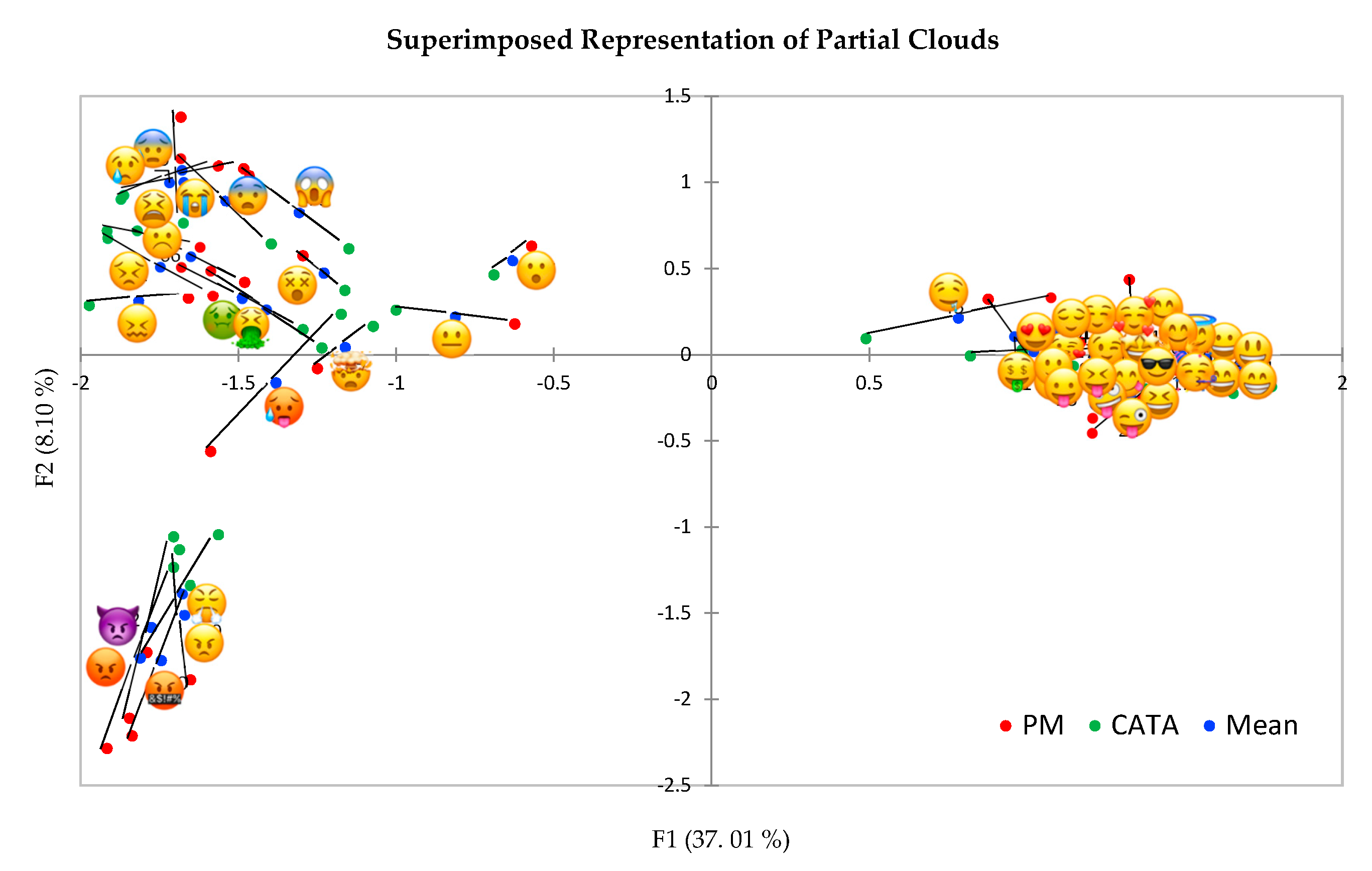

were used also to express “in love” based on the further comments provided by the participants (63%, 35% and 17%, respectively).3.5. Comparing Study 1 and Study 2: Hierarchical Multiple Factor Analysis

, and some other emoji on the top left of Figure 7, and on the second dimension particularly for some negative emoji (the “angry” group and

, and some other emoji on the top left of Figure 7, and on the second dimension particularly for some negative emoji (the “angry” group and  ). Overall, projective mapping discriminated slightly better than CATA the “angry” group,

). Overall, projective mapping discriminated slightly better than CATA the “angry” group,  and

and  , while in other cases in which a difference was found, CATA contributed to further discrimination.

, while in other cases in which a difference was found, CATA contributed to further discrimination.4. Discussion

4.1. Meaning of Emoji: Similarities and Differences

4.2. Associations with Words

and

and  that expressed all “happy”, “cheerful” and “serene” (frequency > than 40%), with small differences, even if not statistically significant: the percentage of association of “cheerful” with the last two emoji was 71 and 64%, respectively.

that expressed all “happy”, “cheerful” and “serene” (frequency > than 40%), with small differences, even if not statistically significant: the percentage of association of “cheerful” with the last two emoji was 71 and 64%, respectively. and

and  were associated not only with “unhappy”, “sad” and “disappointed” but also with “guilty.” Furthermore, the emoji

were associated not only with “unhappy”, “sad” and “disappointed” but also with “guilty.” Furthermore, the emoji  was used to express to be “happy”, “at ease” and “confident.”

was used to express to be “happy”, “at ease” and “confident.”4.3. Gender and Age Differences

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ventura, A.K.; Worobey, J. Early Influences on the Development of Food Preferences. Curr. Boil. 2013, 23, R401–R408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cosmi, V.; Scaglioni, S.; Agostoni, C. Early Taste Experiences and Later Food Choices. Nutrients 2017, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, G. Development of taste and food preferences in children. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2008, 11, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laureati, M.; Pagliarini, E.; Toschi, T.G.; Monteleone, E. Research challenges and methods to study food preferences in school-aged children: A review of the last 15years. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 46, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, J.T.; Shanahan, M.J. (Eds.) Handbook of the Life Course; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 0306482479. [Google Scholar]

- King, S.C.; Meiselman, H.L. Development of a method to measure consumer emotions associated with foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S.; Monteleone, E. Emotional Responses to Products. In Methods in Consumer Research; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 261–296. [Google Scholar]

- Schouteten, J.J.; Verwaeren, J.; Lagast, S.; Gellynck, X.; de Steur, H. Emoji as a tool for measuring children’s emotions when tasting food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, K.E.; Swaney-Stueve, M.; Chambers, E. Comparing visual food images versus actual food when measuring emotional response of children. J. Sens. Stud. 2017, 32, 12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, K.E.; Swaney-Stueve, M.; Chambers, E. A focus group approach to understanding food-related emotions with children using words and emojis. J. Sens. Stud. 2017, 32, e12264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney-Stueve, M.; Jepsen, T.; Deubler, G. The emoji scale: A facial scale for the 21st century. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouteten, J.J.; Verwaeren, J.; Gellynck, X.; Almli, V.L. Comparing a standardized to a product-specific emoji list for evaluating food products by children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sick, J.; Spinelli, S.; Dinnella, C.; Monteleone, E. Children’s selection of emojis to express food-elicited emotions in varied eating contexts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 85, 103953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Dan, Q.; Mu, Z.; Yang, M. A Systematic Review of Emoji: Current Research and Future Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, P.K.; Smailović, J.; Sluban, B.; Mozetič, I.; Kralj Novak, P.; Smailović, J.; Sluban, B.; Mozetič, I. Sentiment of emojis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144296. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, L.; Ares, G.; Jaeger, S.R. Use of emoticon and emoji in tweets for food-related emotional expression. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 49, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.L.; Fugate, J.M.B. Emoji Face Renderings: Exploring the Role Emoji Platform Differences have on Emotional Interpretation. J. Nonverbal. Behav. 2020, 44, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Ares, G. Dominant meanings of facial emoji: Insights from Chinese consumers and comparison with meanings from internet resources. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Roigard, C.M.; Jin, D.; Vidal, L.; Ares, G. Valence, arousal and sentiment meanings of 33 facial emoji: Insights for the use of emoji in consumer research. Food Res. Int. 2018, 119, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brants, W.; Sharif, B.; Serebrenik, A. Assessing the Meaning of Emojis for Emotional Awareness-A Pilot Study. In Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.; Prada, M.; Carvalho, R.; Garrido, M.V.; Lopes, D. Lisbon Emoji and Emoticon Database (LEED): Norms for emoji and emoticons in seven evaluative dimensions. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 50, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Barrett, L.F. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.F. Navigating the Science of Emotion. In Emotion Measurement; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 31–63. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.F. Valence is a basic building block of emotional life. J. Res. Pers. 2006, 40, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, J.R.J.; Scherer, K.R. The global meaning structure of the emotion domain: Investigating the complementarity of multiple perspectives on meaning1. In Components of Emotional Meaning; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2013; Volume 15, pp. 106–126. [Google Scholar]

- Widen, S.C.; Russell, J.A. Children acquire emotion categories gradually. Cogn. Dev. 2008, 23, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, C.; Syssau, A. Affective norms for 720 French words rated by children and adolescents (FANchild). Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 49, 1882–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bahn, D.; Vesker, M.; Alanis, J.C.G.; Schwarzer, G.; Kauschke, C. Age-Dependent Positivity-Bias in Children’s Processing of Emotion Terms. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, S.; Jaeger, S.R. What do we know about the sensory drivers of emotions in foods and beverages? Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 27, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kring, A.M.; Gordon, A.H. Sex Differences in Emotion: Expression, Experience, and Physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Aldao, A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 735–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A.; Matsumoto, D. Gender Differences in Judgments of Multiple Emotions from Facial Expressions. Emotion 2004, 4, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, A.M. Sex differences in social cognition: The case of face processing. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 95, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.L.; Wurm, L.H.; Norville, G.A.; Mullins, K.L. Sex differences in emoji use, familiarity, and valence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lu, X.; Ai, W.; Li, H.; Mei, Q.; Liu, X. Through a Gender Lens. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference on World Wide Web-WWW’18; International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 763–772. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Xia, Y.; Lee, P.Y.; Hunter, D.C.; Beresford, M.K.; Ares, G. Emoji questionnaires can be used with a range of population segments: Findings relating to age, gender and frequency of emoji/emoticon use. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, P. Meaning and Experience; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IA, USA; Indianapolis, IA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valentin, D.; Chollet, S.; Lelièvre, M.; Abdi, H. Quick and dirty but still pretty good: A review of new descriptive methods in food science. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 1563–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, P.; Ares, G. Sensory profiling, the blurred line between sensory and consumer science. A review of novel methods for product characterization. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, P.; Salvador, A. Structured sorting using pictures as a way to study nutritional and hedonic perception in children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 37, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitterer-Daltoé, M.L.; Breda, L.S.; Belusso, A.C.; Nogueira, B.A.; Rodrigues, D.P.; Fiszman, S.; Varela, P. Projective mapping with food stickers: A good tool for better understanding perception of fish in children of different ages. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 57, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emojipedia Apple Emoji List. Available online: https://emojipedia.org/apple/ (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- Laurans, G.; Desmet, P.M.A. Developing 14 animated characters for non-verbal self-report of categorical emotions. J. Des. Res. 2017, 15, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S.; Masi, C.; Dinnella, C.; Zoboli, G.P.; Monteleone, E. How does it make you feel? A new approach to measuring emotions in food product experience. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 37, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Lee, P.-Y.; Xia, Y.; Chheang, S.L.; Roigard, C.M.; Ares, G. Using the emotion circumplex to uncover sensory drivers of emotional associations to products: Six case studies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yik, M.; Russell, J.A.; Steiger, J.H. A 12-point circumplex structure of core affect. Emotion 2011, 11, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R.; Wallbott, H.G.; Summerfield, A.B. Experiencing Emotion: A Cross-Cultural Study; Scherer, K.R., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; ISBN 052130427X. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Spinelli, S.; Ares, G.; Monteleone, E. Linking product-elicited emotional associations and sensory perceptions through a circumplex model based on valence and arousal: Five consumer studies. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J.; Valentin, D.; Bennani-Dosse, M. STATIS and DISTATIS: Optimum multitable principal component analysis and three way metric multidimensional scaling. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2012, 4, 124–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, D.; Lavit, C. Analyse Conjointe de Tableaux Quantitatifs. Biometrics 1990, 46, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavit, C.; Escoufier, Y.; Sabatier, R.; Traissac, P. The ACT (STATIS method). Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 1994, 18, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestrud, M.A.; Lawless, H.T. Perceptual Mapping of apples and cheeses using projective mapping and sorting. J. Sens. Stud. 2010, 25, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, O.; Berget, I.; Næs, T. A comparison of generalised procrustes analysis and multiple factor analysis for projective mapping data. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lé, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoemann, K.; Wu, R.; LoBue, V.; Oakes, L.M.; Xu, F.; Barrett, L.F. Developing an Understanding of Emotion Categories: Lessons from Objects. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Roigard, C.M.; Ares, G. Measuring consumers’ product associations with emoji and emotion word questionnaires: Case studies with tasted foods and written stimuli. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 732–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Somerville, L.H.; Johnstone, T.; Polis, S.; Alexander, A.L.; Shin, L.M.; Whalen, P.J. Contextual Modulation of Amygdala Responsivity to Surprised Faces. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2004, 16, 1730–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S.; Masi, C.; Zoboli, G.; Prescott, J.; Monteleone, E. Emotional responses to branded and unbranded foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; Bergamaschi, V.; Pagliarini, E. Assessing childhood food neophobia: Validation of a scale in Italian primary school children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszkiewicz, A.; Frackowiak, T.; Sorokowska, A.; Sorokowski, P. Children can accurately recognize facial emotions from emoticons. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S. The development of children ages 6 to 14. Future Child. 1999, 9, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are not shown on the right side of the figure because they are overlapped.

are not shown on the right side of the figure because they are overlapped.

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are not shown on the right side of the figure because they are overlapped.

are not shown on the right side of the figure because they are overlapped.

| grinning face |  | drooling face |

| grinning face with big eyes |  | nauseated face |

| grinning face with smiling eyes |  | face vomiting |

| beaming face with smiling eyes |  | hot face |

| grinning squinting face |  | dizzy face |

| slightly smiling face |  | exploding face |

| winking face |  | partying face |

| smiling face with smiling eyes |  | smiling face with sunglasses |

| smiling face with halo |  | frowning face |

| smiling face with hearts |  | face with open mouth |

| smiling face with heart-eyes |  | fearful face |

| star-struck |  | anxious face with sweat |

| face blowing a kiss |  | crying face |

| smiling face |  | loudly crying face |

| face savoring food |  | face screaming fear |

| face with tongue |  | confounded face |

| winking face with tongue |  | persevering face |

| zany face |  | tired face |

| squinting face with tongue |  | face with steam from nose |

| money-mouth face |  | pouting face |

| hugging face |  | angry face |

| neutral face |  | face with symbols on mouth |

| relieved face |  | angry face with horns |

| Dimensions | Emotion Words | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| References | Study 2 (English) | Study 2 (Italian) | |

| I Pleasant Activation | energetic 1,2,3, excited 1,2, sensual 3 | energetic | pieno di energia |

| II Activated Pleasure | enthusiastic 1,2, elated1, inspired 2, amused 3, cheerful 3 | enthusiastic, amused, cheerful | entusiasta, allegro/a, divertito/a |

| III Pleasure | pleased 1, satisfied 1,2,3, happy 2,3, happy memory 3, merry, cuddled 3, gratified 3 | happy, satisfied, cuddled, gratified | felice, soddisfatto/a, coccolato/a, gratificato/a |

| IV Deactivated Pleasure | serene 1, peaceful 1, secure 2,3, at ease 2, generous 3, tender 3, anti-stress 3 (calming, shooting, reassuring) | confident, at ease, reassured | sicuro/a, a mio agio, rassicurato/a |

| V Pleasant Deactivation | placid 1, tranquil 1, relaxed 2,3/carefree 3, calm 2 | relaxed, calm, serene, carefree | rilassato/a, calmo/a, sereno/a, spensierato/a |

| VI Deactivation | quiet 1,2, still 1, passive 2, indifferent 3 | indifferent, quiet | indifferente, tranquillo/a |

| VII Unpleasant Deactivation | sluggish 1,tired 1, dulled 2, bored 2,3 | bored | annoiato/a |

| VIII Deactivated Displeasure | sad 1,3, gloomy 1, blue 2, uninspired 2 | sad, melancholic | triste, malinconico/a |

| IX Displeasure | unhappy 1,2, dissatisfied 1,2, neglected 3, disappointed 3 | unhappy, dissatisfied, disappointed | infelice, insoddifatto/a, deluso/a |

| X Activated Displeasure | distressed 1, upset 1, tense 2, bothered 2, guilty 3 | guilty | in colpa |

| XI Unpleasant Activation | frenzied 1, jittery 1, 2, nervous 2, annoyed 3 | annoyed, disgusted, angry, worried | infastidito/a, disgustato/a, arrabbiato/a, preoccupato/a |

| XII Activation | aroused 1, activated 1, active 2, alert 2, surprised 3, curious 3 | surprised, curious | sorpreso/a, incuriosito/a |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sick, J.; Monteleone, E.; Pierguidi, L.; Ares, G.; Spinelli, S. The Meaning of Emoji to Describe Food Experiences in Pre-Adolescents. Foods 2020, 9, 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091307

Sick J, Monteleone E, Pierguidi L, Ares G, Spinelli S. The Meaning of Emoji to Describe Food Experiences in Pre-Adolescents. Foods. 2020; 9(9):1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091307

Chicago/Turabian StyleSick, Julia, Erminio Monteleone, Lapo Pierguidi, Gastón Ares, and Sara Spinelli. 2020. "The Meaning of Emoji to Describe Food Experiences in Pre-Adolescents" Foods 9, no. 9: 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091307

APA StyleSick, J., Monteleone, E., Pierguidi, L., Ares, G., & Spinelli, S. (2020). The Meaning of Emoji to Describe Food Experiences in Pre-Adolescents. Foods, 9(9), 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091307