Establishing a Rapid Enrichment Medium for Bacillus cereus to Shorten Detection Time

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains in This Study

2.2. Screening of Basal Media for Promoting the Growth of B. cereus

2.3. Growth Curve Plotting and Post-Germination Recovery of B. cereus Spores’ Assay

2.4. Optimization of the Addition Amounts of Promoters and Inhibitors

2.5. Establishment of the Thermal Injury Model of B. cereus and Determination of the Recovery Effect

2.6. Detection of Artificially Contaminated Dairy Samples by B. cereus

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

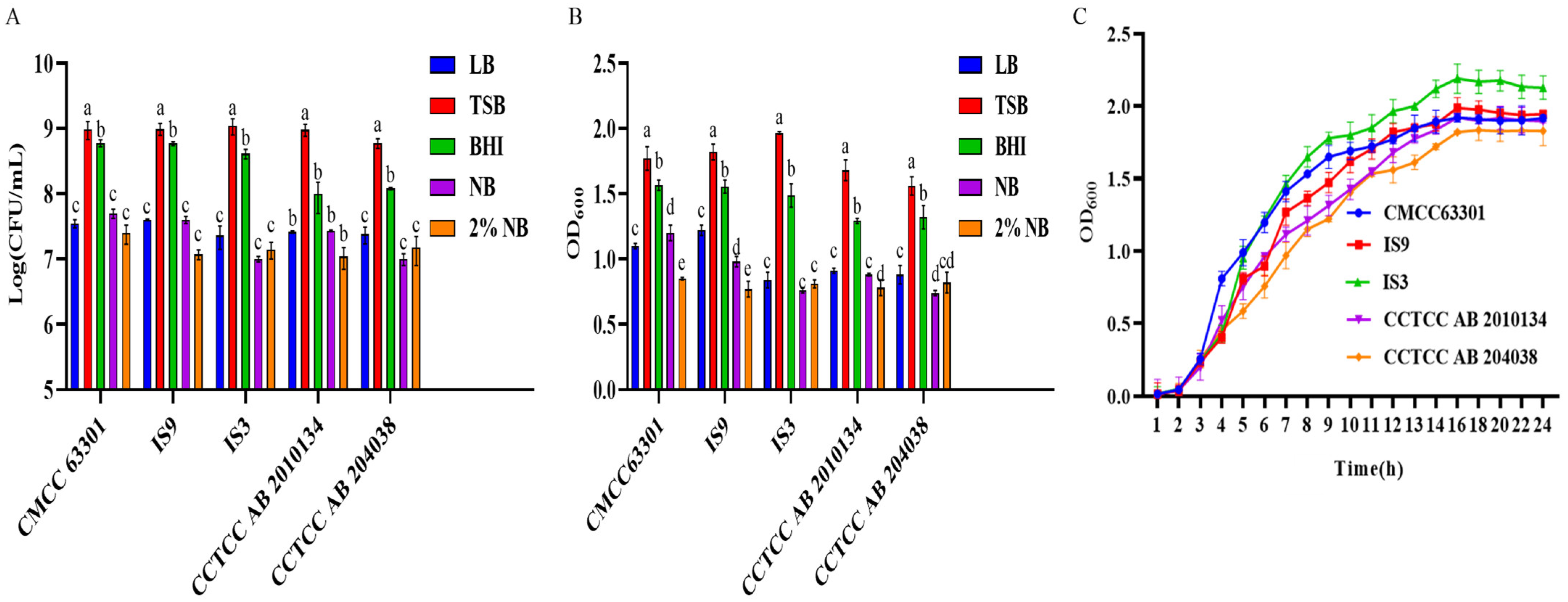

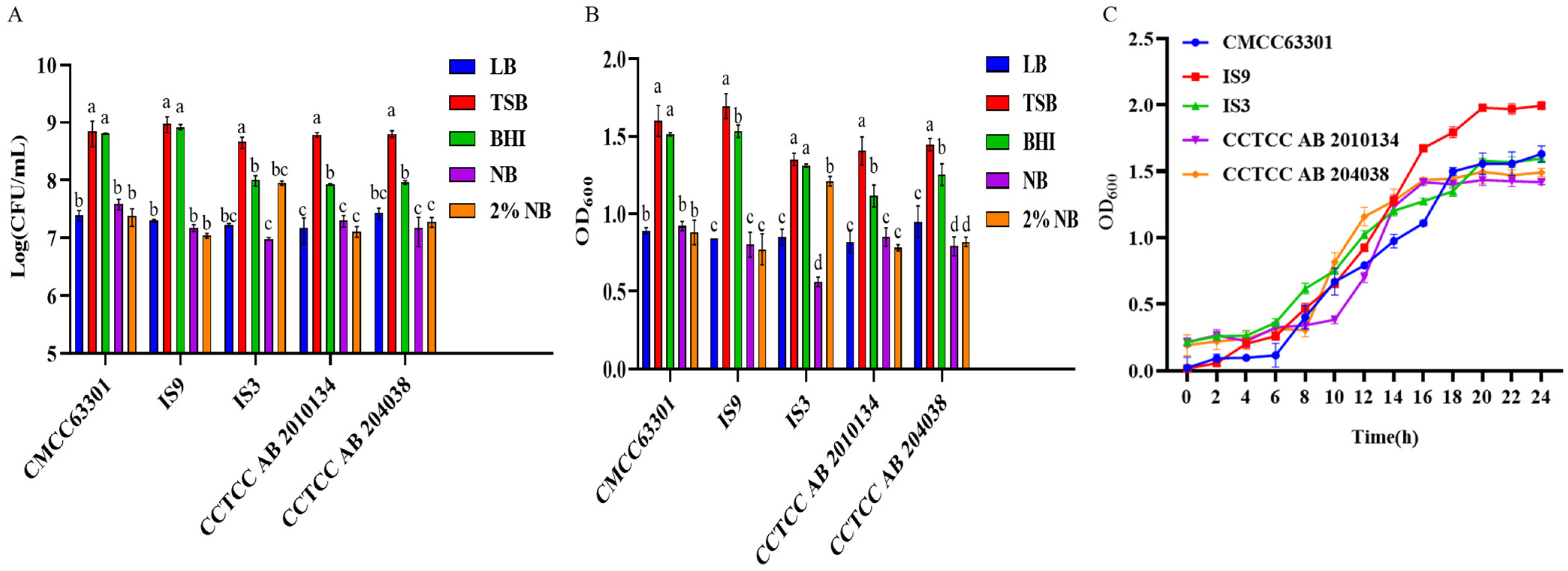

3.1. Nutrient Media Screening for B. cereus

3.2. Effect of Basal Media on Post-Germination Recovery of Bacillus cereus Spores

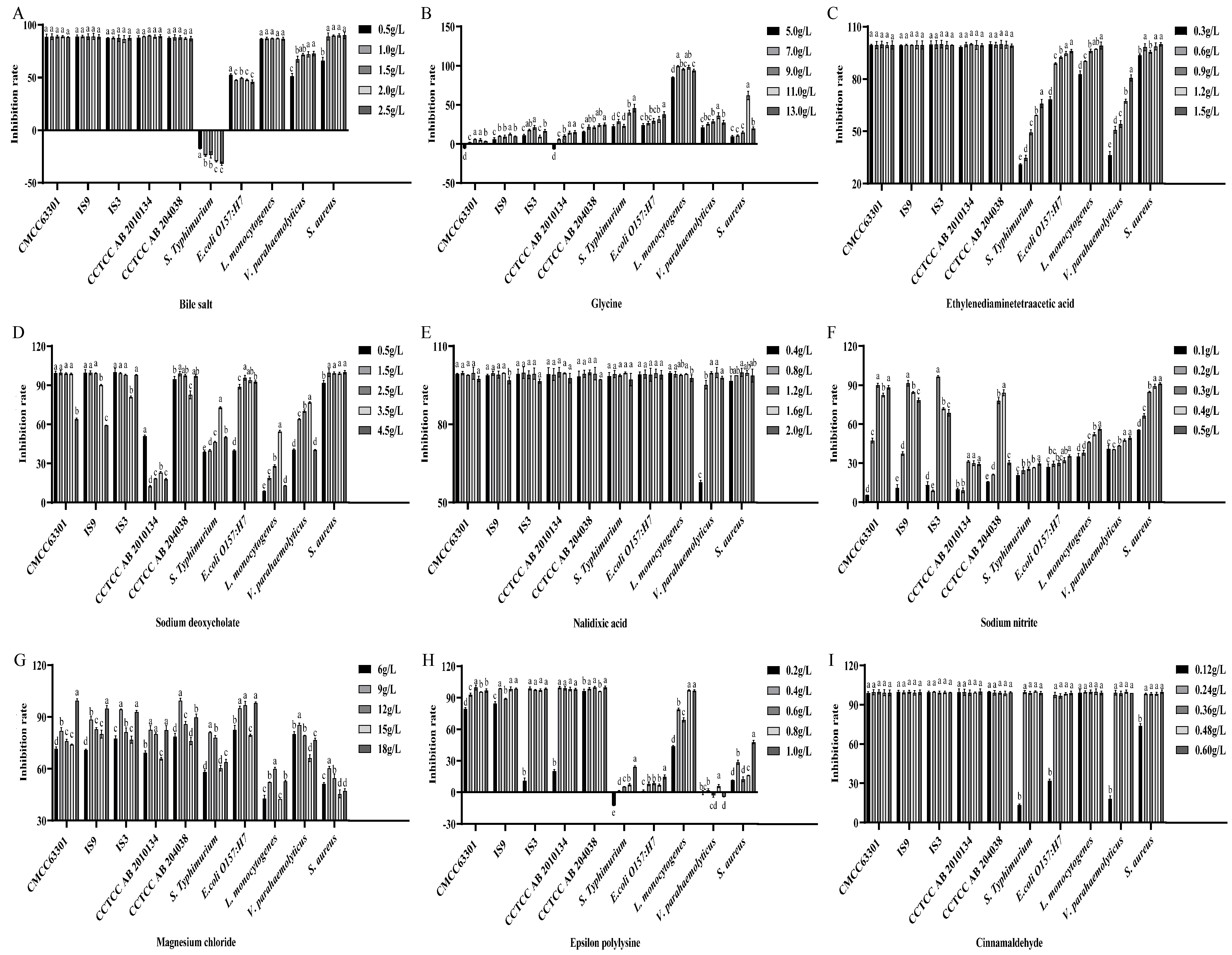

3.3. Selection of Promoters for Target Bacteria and Inhibitors for Non-Target Bacteria

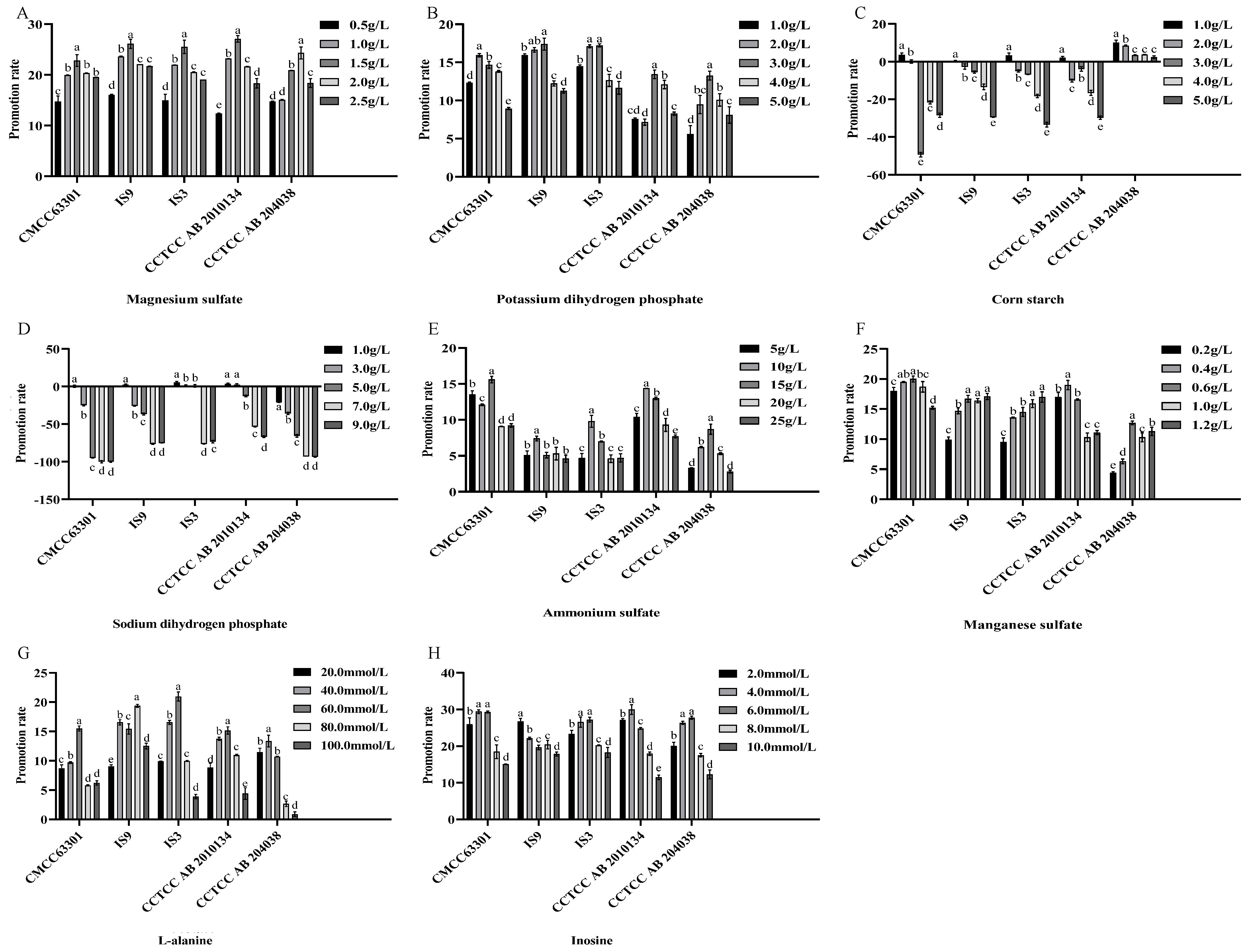

3.4. Optimization of the Formulation of Rapid Enrichment Medium

3.5. Promoting effects of BC-TSB on bacterial growth and spore germination

3.6. Thermal Injury Recovery of B. cereus and Detection in Artificially Contaminated Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B. cereus | Bacillus cereus |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

| PMAxx-qPCR | PMAxx-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| LB | Linear dichroism |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

References

- Jovanovic, J.; Ornelis, V.F.M.; Madder, A.; Rajkovic, A. Bacillus cereus food intoxication and toxicoinfection. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3719–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirloni, E.; Stella, S.; Celandroni, F.; Mazzantini, D.; Bernardi, C.; Ghelardi, E. Bacillus cereus in dairy products and production plants. Foods 2022, 11, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellouze, M.; Da Silva, N.B.; Rouzeau-Szynalski, K.; Coisne, L.; Cantergiani, F.; Baranyi, J. Modeling Bacillus cereus growth and cereulide formation in cereal-, dairy-, meat-, vegetable-based food and culture medium. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.W.M.; El Latif, H.H.A.; Ali, S.M. Production of Cold-Active Lipase by Free and Immobilized Marine Bacillus cereus HSS: Application in Wastewater Treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messelhäußer, U.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Bacillus cereus—A multifaceted opportunistic pathogen. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2018, 5, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzeau-Szynalski, K.; Stollewerk, K.; Messelhäusser, U.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Why be serious about emetic Bacillus cereus: Cereulide production and industrial challenges. Food Microbiol. 2020, 85, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Flint, S.H.; Palmer, J.S. Bacillus cereus spores and toxins—The potential role of biofilms. Food Microbiol. 2020, 90, 103493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Wang, D.; Zou, M.; Wang, W.; Ma, X.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Ding, T.; Ye, X.; Liu, D. Analysis of Bacillus cereus cell viability, sublethal injury, and death induced by mild thermal treatment. J. Food Saf. 2019, 39, e12581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Genovés, S.; Martorell, P.; Zanini, S.; Rodrigo, D.; Martinez, A. Sublethal injury and virulence changes in Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua treated with antimicrobials carvacrol and citral. Food Microbiol. 2015, 50, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7932:2004; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Presumptive Bacillus cereus—Colony-Count Technique at 30 Degrees C. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Ramarao, N.; Tran, S.-L.; Marin, M.; Vidic, J. Advanced methods for detection of Bacillus cereus and its pathogenic factors. Sensors 2020, 20, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talahmeh, N.; Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Al-Razem, F. Development of a selective and differential media for the isolation and enumeration of Bacillus cereus from food samples. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidic, J.; Chaix, C.; Manzano, M.; Heyndrickx, M. Food sensing: Detection of Bacillus cereus spores in dairy products. Biosensors 2020, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerton, B.T.; Morgan, B.L. Comparison of plate counting with flow cytometry, using four different fluorescent dye techniques, for the enumeration of Bacillus cereus in milk. J. Microbiol. Methods 2024, 223, 106978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, V.; Condón, S.; Gayán, E. Impact of sporulation temperature on germination of Bacillus subtilis spores under optimal and adverse environmental conditions. Food Res. Int. 2024, 182, 114064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchon, S.; Dargaignaratz, C.; Levy, C.; Ginies, C.; Broussolle, V.; Carlin, F. Spores of Bacillus cereus strain KBAB4 produced at 10 °C and 30 °C display variations in their properties. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-Uribe, L.F.; Romero-Tabarez, M.; Villegas-Escobar, V. Effect of medium components and culture conditions in Bacillus subtilis EA-CB0575 spore production. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallent, S.M.; Knolhoff, A.; Rhodehamel, E.J.; Stanley, M.H.; Reginald, W.B. BAM chapter 14: Bacillus cereus. In Bacteriological Analytical Manual; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Hu, A.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wei, W.; Lu, F.; Zhao, H.; Bie, X. Construction and optimization of a multiplex PMAxx-qPCR assay for viable Bacillus cereus and development of a detection kit. J. Microbiol. Methods 2023, 207, 106705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Brightwell, G. Effect of novel and conventional food processing technologies on Bacillus cereus spores. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2024, 108, 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Teramura, H.; Otsubo, M.; Saito, H.; Ishii, A.; Suzuki, M.; Ogihara, H. Comparative evaluation of selective media for the detection of Bacillus cereus. Biocontrol Sci. 2019, 24, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Flint, S.; Palmer, J. Magnesium and calcium ions: Roles in bacterial cell attachment and biofilm structure maturation. Biofouling 2019, 35, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.G.; Orr, J.S.; Rao, C.V.; Wolfe, A.J. Increasing growth yield and decreasing acetylation in Escherichia coli by optimizing the carbon-to-magnesium ratio in peptide-based media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e03034-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makkar, R.S.; Cameotra, S.S. Effects of various nutritional supplements on biosurfactant production by a strain of Bacillus subtilis at 45 °C. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2002, 5, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounina-Allouane, R.; Broussolle, V.; Carlin, F. Influence of the sporulation temperature on the impact of the nutrients inosine and l-alanine on Bacillus cereus spore germination. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornstra, L.M.; de Vries, Y.P.; de Vos, W.M.; Abee, T.; Wells-Bennik, M.H. gerR, a novel ger operon involved in L-alanine-and inosine-initiated germination of Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, M.; Ando, T.; Hashikawa, S.-N.; Torii, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Israel, D.A.; Ina, K.; Kusugami, K.; Goto, H.; Ohta, M. Effect of glycine on Helicobacter pylori in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3782–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishinuma, F.; Izaki, K.; Takahashi, H. Effects of glycine and D-amino acids on growth of various microorganisms. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1969, 33, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Fraqueza, M.J.; Laranjo, M.; Elias, M.; Patarata, L. Microbiological hazards associated with salt and nitrite reduction in cured meat products: Control strategies based on antimicrobial effect of natural ingredients and protective microbiota. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 38, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husakova, M.; Plechata, M.; Branska, B.; Patakova, P. Effect of a Monascus sp. red yeast rice extract on germination of bacterial spores. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 686100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhu, N.; Jin, J.; Xu, Z.; Wei, T.; Yu, R. Research progress on the injury mechanism and detection method of disinfectant-injured Escherichia coli in the drinking water system. AQUA—Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2021, 70, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schottroff, F.; Fröhling, A.; Zunabovic-Pichler, M.; Krottenthaler, A.; Schlüter, O.; Jäger, H. Sublethal injury and viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state in microorganisms during preservation of food and biological materials by non-thermal processes. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, A.K.; Tempelaars, M.H.; Abee, T.; Groot, M.N.N. Recovery of heat treated bacillus cereus spores is affected by matrix composition and factors with putative functions in damage repair. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktabdar, M.; Wemmenhove, E.; Gkogka, E.; Dalgaard, P. Development of extensive growth and growth boundary models for mesophilic and psychrotolerant Bacillus cereus in dairy products (Part 1). Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1553885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imade, E.E.; Omonigho, S.E.; Babalola, O.O.; Enagbonma, B.J. Lactic acid bacterial bacteriocins and their bioactive properties against food-associated antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shi, C.; Hu, R.; Zhou, H.; Bie, X.; Yang, J. Establishing a Rapid Enrichment Medium for Bacillus cereus to Shorten Detection Time. Foods 2026, 15, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030466

Shi C, Hu R, Zhou H, Bie X, Yang J. Establishing a Rapid Enrichment Medium for Bacillus cereus to Shorten Detection Time. Foods. 2026; 15(3):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030466

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Changzheng, Ruirui Hu, Haibo Zhou, Xiaomei Bie, and Jun Yang. 2026. "Establishing a Rapid Enrichment Medium for Bacillus cereus to Shorten Detection Time" Foods 15, no. 3: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030466

APA StyleShi, C., Hu, R., Zhou, H., Bie, X., & Yang, J. (2026). Establishing a Rapid Enrichment Medium for Bacillus cereus to Shorten Detection Time. Foods, 15(3), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030466