Experimental Study on the Influence of Different Loading Weights and Placement Forms on Vacuum Sublimation–Rehydration Thawing of Large Yellow Croaker

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. System Fundamentals and Components

3. Experimental Procedures and Data Processing

3.1. Experimental Procedures

3.1.1. Preparation of Samples

- (1)

- The fresh large yellow croaker samples (250 ± 3 g) were bought from Shanghai Luchao Port (Shanghai, China). They were stored in a large amount of ice cubes, and transported to the laboratory within 1 h.

- (2)

- Random samples of large yellow croakers with uniform specifications were selected for the experiments. The initial parameters of chosen fish samples were as follows: mass of 250 ± 3 g, brightness of 77.20 ± 0.11, redness of 4.49 ± 0.09, yellowness of 26.85 ± 0.10, pH of 6.51 ± 0.01, hardness of 2416.8 ± 151.2 gram-force (gf), springiness of 0.73 ± 0.02, adhesiveness of 6.84 ± 0.38 g·s and cohesion of 0.36 ± 0.03.

- (3)

- As shown in Figure 2, thermocouples (with a diameter of 0.2 cm) were inserted at designated measurement points in fish samples, which were used to measure the upper surface temperature (insertion depth of 0.2 cm), core temperature (insertion depth of 2 cm) and bottom surface temperature (insertion depth of 0.2 cm) of fish samples.

- (4)

- According to the standards of SC/T3101-2010 [29] and NYT3524-2019 [30], the core temperatures of fish samples were set at −18 °C as the initial thawing temperature. The target thawing temperature was defined as 4 °C (the fastest-thawed fish sample), while the core temperatures of remaining fish samples were maintained between 0 °C and 4 °C.

- (5)

- All fish samples were first frozen in a −40 °C freezer for 10 h until their core temperatures reached −18 °C [31]. Following this, they were transferred to a −18 °C freezer for 10 h storage. After completing the above operations, take fish samples from the freezer for experiments. The freezers used were air-cooled freezers (Model: BD/BC-100KEMS) produced by Midea Group Co., Ltd. (Foshan, China), with a minimum cooling temperature of −40 °C and a maximum freezer load of 100 L.

3.1.2. Experiment of VSRT

3.1.3. Experiment of AT

3.1.4. Experiment of VST

3.2. Evaluation Indexes

3.2.1. Thawing Efficiency (Thawing Time, Thawing Rate, Specific Thawing Time)

3.2.2. Thawing Uniformity

3.2.3. Thawing Loss

3.2.4. Moisture Content

3.2.5. Color Difference

3.2.6. pH Parameter

3.2.7. Texture Parameters

3.2.8. Specific Energy Consumption (SEC) Parameter

3.3. Normalization Evaluation

3.4. Uncertainty Analysis and Data Statistics

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Influence of Different Loading Weights on VSRT

4.1.1. Thawing Process

4.1.2. Thawing Efficiency and Thawing Uniformity

4.1.3. Thawing Loss and Moisture Content

4.1.4. Color

4.1.5. pH

4.1.6. Texture Parameter

4.1.7. Specific Energy Consumption (SEC)

4.1.8. Comprehensive Evaluation with Different Loading Weights

4.2. Influence of Different Placement Forms on VSRT

4.2.1. Influence of Different Placement Forms on Thawing Efficiency and Thawing Uniformity

- (1)

- Placement Form A: The fish samples were positioned closest to the rehydration input ports, allowing water vapor to diffuse most rapidly to fish samples. Therefore, the condensation efficiency was enhanced, leading to the highest thawing efficiency. However, the excessively wide PWF-Fs were not conducive to the uniform diffusion of water vapor, which declined the thawing uniformity.

- (2)

- Placement Form B: The fish samples were positioned closer to the rehydration input ports, and the widths of PWF-Fs were moderate. This placement form not only facilitated rapid vapor diffusion to fish samples, but also supported the most uniform condensation heat exchange. Thus, the thawing efficiency was the higher and the thawing uniformity was optimal.

- (3)

- Placement Forms C and D: The fish samples were positioned farther from the rehydration input ports, which slowed the water vapor diffusion to fish samples, resulting in extended thawing time. Additionally, the continuous arrangement of fish samples formed barriers that caused uneven diffusion of water vapor, which declined the thawing uniformity. The double-row uniform placement (Placement Form C) mitigated barriers from outer samples, resulting in better thawing efficiency and improved thawing uniformity compared to those of Placement Form D.

- (4)

- Placement Form E: The fish samples were positioned the farthest from the rehydration input ports and the PWF-Fs were too narrow, which collectively resulted in the poorest thawing efficiency and thawing uniformity.

4.2.2. Influence of Different Placement Forms on Thawing Effect and Total SEC

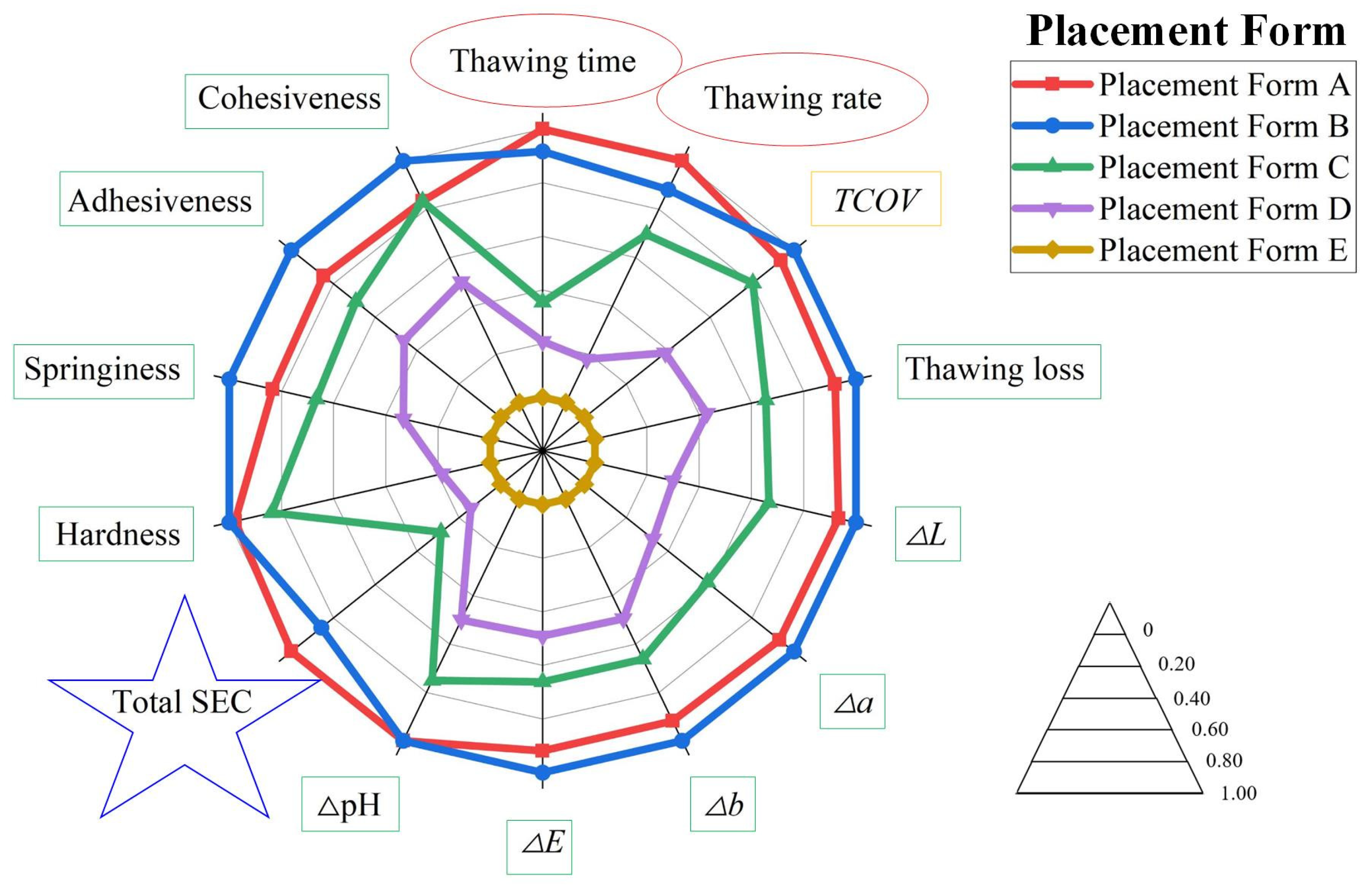

4.2.3. Comprehensive Evaluation with Different Placement Forms

4.3. Comparison of Different Thawing Methods

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The increase in loading weight resulted in a reduced ice crystal sublimation ratio and the alteration of pathways between adjacent fish samples, which was a key factor influencing vacuum sublimation–rehydration thawing. Based on the experimental system and operation conditions (with constant sublimation time of 20 min, constant DH-F of 80 mm, constant rehydration temperature of 35 °C, and constant heating plate temperature of 35 °C) in this paper, a loading weight of 1000 g (i.e., a loading ratio of 9.06 kg/m3) was determined to be optimal, resulting in the water vapor distribution that was most suitable for the operation conditions. This loading weight promoted efficient and uniform condensation heat exchange, which led to the highest thawing uniformity (lowest TCOV of 4.22%) and the best thawing effect (lowest thawing loss of 1.24%, highest moisture content of 73.33%, minimum ΔpH of +0.02, optimal color, and superior texture parameters). In addition, the thawing efficiency was higher and the total SEC was lower (2.243 MJ/kg) at a loading weight of 1000 g. The loading weight of 2000 g (i.e., the loading ratio of 18.12 kg/m3) was determined to be the maximum for rapid thawing, achieving the shortest specific thawing time (67.83 min/kg), which represented the limiting loading weight for rapid thawing. At a loading weight of 2500 g (i.e., a loading density of 22.65 kg/m3), although the lowest total specific energy consumption was achieved (1.110 MJ/kg), it performed relatively the worst in terms of thawing efficiency, thawing uniformity and thawing efficiency. For ultra-large-scale industrial thawing, the required energy consumption was extremely high. If appropriately reducing the quality of thawed food could still meet market demands, the loading density could be increased to 22.65 kg/m3 to ensure significant electricity savings.

- (2)

- Different placement forms altered the diffusion path of water vapor, leading to variations in water vapor condensation efficiency, which also significantly influencing vacuum sublimation–rehydration thawing. Applying staggered placement forms was able to provide moderate widths of pathways between adjacent fish samples, and maintain closer distances among the large yellow croakers and rehydration input ports, which promoted efficient and uniform condensation heat exchange between water vapor and fish samples. Thus, the best thawing uniformity (minimum TCOV of 3.78%) and the optimal thawing effect (the lowest thawing loss of 0.98%; highest moisture content of 73.59%; minimum ΔpH of +0.01; optimal color; superior texture parameters) were achieved. Moreover, the staggered placement form also resulted in higher thawing efficiency and lower total SEC (2.185 MJ/kg).

- (3)

- Compared with air thawing and vacuum steam thawing, the key advantage of vacuum sublimation–rehydration thawing lay in the formation of tiny pores within frozen food through ice crystal sublimation. This process promoted more uniform and efficient condensation heat exchange between water vapor and large yellow croakers, which improved thawing efficiency and thawing uniformity and obtained optimal thawing loss, pH, color and texture parameters. Additionally, compared with vacuum steam thawing, the total SEC of vacuum sublimation–rehydration thawing was reduced by 76.17~81.53%.

- (4)

- Based on the experimental system and operation conditions in this paper, the recommended loading weight for a high-quality food processing scenario was 1000 g (i.e., loading ratio of 9.06 kg/m3) combined with a staggered placement form. This combination could quickly obtain the optimal quality of large yellow croakers and further reduce energy consumption. For scenarios prioritizing higher production capacity, the loading weight could be increased to the maximum of 2000 g (i.e., loading ratio of 18.12 kg/m3). However, it must be ensured that the resulting decline in evaluation indexes, such as thawing uniformity, remain within an acceptable range.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, W.X.; Min, W.Z.; Qiang, W.Z.; Qing, Z.; Xiang, Z.Q.; Bo, Y.H.; Lan, Z.L.; Jie, C.; Xin, L.D. Prediction method of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) freshness based on improved residual neural network. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 2995–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Ni, J.; Wu, J.T.; Shen, J. Influence of Thawing Methods on Thawing Efficiency and Quality of Pseudosciaena crocea. Meat Res. 2016, 30, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Yan, J.K.; Rashid, M.T.; Ding, Y.H.; Chikari, F.; Huang, S.F.; Ma, H.L. Dual-frequency sequential ultrasound thawing for improving the quality of quick-frozen small yellow croaker and its possible mechanisms. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 68, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.P.; Qin, N.; Zhang, L.T.; Li, Q.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Luo, Y.K. Degradation of adenosine triphosphate, water loss and textural changes in frozen common carp (Cyprinus carpio) fillets during storage at different temperatures. Int. J. Refrig.-Rev. Int. Froid 2019, 98, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Ma, X.; Xie, J. Review on Natural Preservatives for Extending Fish Shelf Life. Foods 2019, 8, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Bian, C.H.; Chu, Y.M.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Effects of Dual-Frequency Ultrasound-Assisted Thawing Technology on Thawing Rate, Quality Properties, and Microstructure of Large Yellow Croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea). Foods 2022, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Dual-frequency ultrasound-assisted thawing: Enhancement on quality attributes, myofibril characteristics, and microstructure of large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) during frozen to refrigeration. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 15, 5658–5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.M.; Tan, M.T.; Bian, C.H.; Xie, J. Effect of ultrasonic thawing on the physicochemical properties, freshness, and protein-related properties of frozen large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea). J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.R.; Bian, C.H.; Dong, Y.X.; Xie, J.; Mei, J. Effects of different power multi-frequency ultrasound-assisted thawing on the quality characteristics and protein stability of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Food Chem.-X 2024, 23, 101559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Bai, X.; Du, X.; Pan, N.; Shi, S.; Xia, X.F. Comparison of Effects from Ultrasound Thawing, Vacuum Thawing and Microwave Thawing on the Quality Properties and Oxidation of Porcine Longissimus Lumborum. Foods 2022, 11, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, L.S.; Jeong, K.E.; Hyeon, P.D.; Jung, C.M. Two-stage air thawing as an effective method for controlling thawing temperature and improving the freshness of frozen pork loin. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 140, 110668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.W.; Han, R.W.; Yuan, M.D.; Xi, Q.; Du, Q.J.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.X.; Bruce, A.; Wang, J. Ultrasound combined with slightly acidic electrolyzed water thawing of mutton: Effects on physicochemical properties, oxidation and structure of myofibrillar protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 93, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.Y.; Cao, M.J.; Cao, A.L.; Joe, R.; Li, J.R.; Guan, R.F. Ultrasound or microwave vacuum thawing of red seabream (Pagrus major) fillets. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 47, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.W.; Xie, J.; Zhou, R.; Tang, Y.R.; Zhou, Y. Effect of vacuum-steam thawing on the quality of tuna. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2013, 34, 84–87+92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Qin, Z.S.; Song, J.Y.; Bian, L.F.; Yang, C. A study on the visualization of ultrasound-assisted thawing process of frozen carrots using an in-situ schlieren imaging system. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 100, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Yang, Z.S.; Zhang, Y.l.; Pu, A.F.; Feng, Y.Q.; Liu, G.S.; He, J.G. Effect of microwave thawing on muscle food quality: A review. Food Control 2025, 175, 111318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan Koç, G.; Özkan Karabacak, A.; Sufer, O.; Adal, S.; Celebi, Y.; Delikanlı Kıyak, B.; Oztekin, S. Thawing frozen foods: A comparative review of traditional and innovative methods. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, W.D.; Chen, S.S.; Zhou, Z.G. Experimental Investigation on A Novel Vacuum Thawing Method and Its System Performance. Vac. Cryog. 2020, 26, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopec, A.; Mierzejewska, S.; Bac, A.; Diakun, J.; Piepiórka-Stepuk, J. Modification of the vacuum-steam thawing method of meat by using the initial stage of sublimation dehydration. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.L.; Zhang, J.D.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.H. Ultrasonic Rapid Thawing Equipment Applied to the Ship Environment. Technol. Wind 2023, 28, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.K. Efficient Batch Unfreezing System for Frozen Food. China Patent CN213246744U, 25 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.K.; Wu, J.Y.; Huang, D. Cryopreservation Device Capable of Unfreezing in Batches. China Patent CN221071477U, 6 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.R.; Wu, W.D.; Chen, S.S.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Z.G. Experimental study on a novel vacuum sublimation-rehydration thawing of frozen potatoes. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 4146–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.M.; Koop, T. Review of the vapour pressures of ice and supercooled water for atmospheric applications. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. J. Atmos. Sci. Appl. Meteorol. Phys. Oceanogr. 2005, 131, 1539–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.S.; Wu, W.D.; Mao, S.J.; Li, K.; Zhang, H. Optimization of a novel vacuum sublimation-rehydration thawing process. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedov, M.N. On the accuracy of the Clausius-Clapeyron relation. Vacuum 2023, 217, 112494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Quiroga, E.; Antelo, L.T.; Alonso, A.A. Time-scale modeling and optimal control of freeze-drying. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, W.; Xu, N.; Xue, A.; Su, M. Experimental study on the effect of symmetrical heat source on vacuum sublimation-rehydration thawing of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Food Bioprod. Process. 2025, 153, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SC/T3101-2010; Fresh and Frozen Large Yellow Croaker and Fresh and Frozen Small Yellow Croaker. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- NYT3524-2019; Technical Specification for Thawing Frozen Meat. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Chu, Y.M.; Cheng, H.; Yu, H.J.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Quality enhancement of large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) during frozen (−18 °C) storage by spiral freezing. Cyta-J. Food 2021, 19, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.Q.; Zou, T.H.; Zhang, K.S.; Han, X.W. Effect of vacuum thawing process on pork quality. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 44, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J.; Park, H.W.; Chung, Y.B.; Park, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Chun, H.H. Effect of tempering methods on quality changes of pork loin frozen by cryogenic immersion. Meat Sci. 2017, 124, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.L.; Li, X.B.; Yan, L.P.; Ma, H.J.; Xu, X.L.; Zhou, G.H. Effects of different freezing and thawing rate on water-holding capacity and ultrastructure of pork. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2007, 8, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.W.; Jia, Y.Z.; Li, Y. Microwave Oven Food Thawing Control Method and Microwave Oven. China Patent CN104235903A, 24 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Wang, J.F.; Xie, J. Numerical Simulation of Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow at Different Stacking Modes in a Refrigerated Room: Application of Pyramidal Stacking Modes. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Yan, J.K.; Ding, Y.H.; Ma, H.L. Effects of ultrasound on the thawing of quick-frozen small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) based on TMT-labeled quantitative proteomic. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.3-2016; Technical Specification for Thawing Frozen Meat. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Farahnak, R.; Nourani, M.; Riahi, E. Ultrasound thawing of mushroom (Agaricus bisporus): Effects on thawing rate, protein denaturation and some physical properties. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 151, 112150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Guan, Z.Q.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.Y.; Ma, C.F. Effect of vacuum-steam thawing on the quality of tilapia fillets. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2016, 37, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.S.; Wu, W.D.; Yang, Y.Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H. Experimental study of a novel vacuum sublimation-rehydration thawing for frozen pork. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 118, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsomboonthong, S. Performance Comparison of New Adjusted Min-Max with Decimal Scaling and Statistical Column Normalization Methods for Artificial Neural Network Classification. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 2022, 2022, 3584406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffin, T.E.; Smith, M.A.; Bush, R.D.; Collins, D.; Hopkins, D.L. The effect of electrical stimulation and tenderstretching on colour and oxidation traits of alpaca (Vicunga pacos) meat. Meat Sci. 2019, 156, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.L.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.D.; Yang, P.; Ding, Y.T. Effects of dry ice freezing on ice crystal and quality of large yellowcroaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) during frozen storage. Food Mach. 2023, 39, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.Q.; Wu, G.Y.; Lin, H.X.; Jia, W.; Liu, C.J.; Zhang, C.H.; Li, X. Preliminary investigation on the mechanism of electromagnetic coupling to reduce thawing loss of frozen beef. Food Bioprod. Process. 2025, 153, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhang, M.; Qiao, J.S.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Lei, C.Y. High Voltage Electrostatic Field (HVEF) Based Advanced Thawing: Effects of Thawing Process and Frozen Raw Meat Quality. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 7502–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropotova, J.; Tappi, S.; Genovese, J.; Rocculi, P.; Dalla Rosa, M.; Rustad, T. The combined effect of pulsed electric field treatment and brine salting on changes in the oxidative stability of lipids and proteins and color characteristics of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Heliyon 2021, 7, e05947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottestad, S.; Enersen, G.; Wold, J.P. Effect of Freezing Temperature on the Color of Frozen Salmon. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, S423–S427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, N.N.; Guo, L.N.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Lu, F.; Jamila, T.; Ma, H.L. Effect of ultrasonic rapid thawing on the quality of frozen pork and numerical simulation. J. Food Eng. 2025, 387, 112344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instruments/Equipment | Manufacturers/Brands | Parameters | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roots pump | Jiangyin Tiantian Vacuum Equipment Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (ZJP-70), Jiangyin, China | Ultimate pressure: 0.05 Pa | ±0.01 Pa |

| Rotary vane pump | Leybold SOGEVAC (SV40B), Dresden, Germany | Ultimate pressure: 150 Pa | ±1 Pa |

| Water vapor generator | Beijing Yong Guangming Medical Instruments (SXTW), Beijing, China | 0~399 °C | ±1 °C |

| Omron thermostat | Omron (E5CC-800), Tokyo, Japan | 20~180 °C | ±0.5 °C |

| Texture analyzer | Stable Micro System (TA-XT2i), Surrey, UK | Test distance: 0.1~300 mm Test stress: 0~50 kg Test speed: 0.01~40 mm/s | ±0.001 mm ±0.1 g |

| Power meter | UNI-T (UT230E), Dongguan, China | 0.001~9999 kWh | ±1% Rdg |

| Pressure sensor | GE-Druck (UNIK5000), Billerica, MA, USA | 0~100 kPa | ±0.04% FS |

| Mass sensor | Jinnuo (JLBS-M2), Beijing, China | 0~3000 g | ±0.5 g |

| Temperature sensor | Omega v.8.0.0. (T-type, TT-T-30-SLE), Norwalk, CT, USA | −200~350 °C | ±0.5 °C |

| Colorimeter | Konica Minolta (CR-400), Tokyo, Japan | 0.01~160% (reflectivity) | ±6% FS |

| pH meter | Sigma Instruments (PH8180-0-00), Luoyang, China | 0.00~14.00 pH | ±0.05 pH |

| Electronic balance | Sartorius (BSA3202S), Göttingen, Germany | 0~3.2 kg | ±0.01 g |

| Loading Weight | Sample Number | Sample Size | Dx | Dy | DF-R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 g | 2 | 70 mm × 190 mm | 100 mm | - | 180 mm |

| 1000 g | 4 | 70 mm × 190 mm | 100 mm | 10 mm | 180 mm |

| 1500 g | 6 | 70 mm × 190 mm | 47.5 mm | 10 mm | 147.5 mm |

| 2000 g | 8 | 70 mm × 190 mm | 24 mm | 10 mm | 124 mm |

| 2500 g | 10 | 70 mm × 190 mm | 8 mm | 10 mm | 109 mm |

| Before Thawing | Sublimation Stage Completed | Rehydration Stage Completed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 (g) | Mi (g) | M0 − Mi (g) | Ice Crystal Sublimation Ratio (M0 − Mi)/M0 | M1 (g) | M1 − Mi (g) | Water Replenishment Ratio (M1 − Mi)/M0 |

| 500 | 472.92 | 27.08 | 5.42% | 491.66 | 18.74 | 3.75% |

| 1000 | 949.48 | 50.52 | 5.05% | 987.57 | 38.09 | 3.81% |

| 1500 | 1443.54 | 56.46 | 3.76% | 1479.03 | 35.49 | 2.37% |

| 2000 | 1935.76 | 64.24 | 3.21% | 1968.82 | 33.06 | 1.65% |

| 2500 | 2435.50 | 64.50 | 2.58% | 2447.09 | 11.59 | 0.46% |

| Loading Weight/State | Thawing Loss (%) | Moisture Content (%) | L | a | b | ΔE | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh sample | 74.57 ± 0.05 a | 77.20 ± 0.11 a | 4.49 ± 0.09 a | 26.85 ± 0.10 b | - | 6.51 ± 0.01 b | |

| 500 g | 1.67 ± 0.06 a | 72.90 ± 0.06 b | 76.83 ± 0.09 a | 3.82 ± 0.10 b | 31.13 ± 0.11 a | 4.35 ± 0.17 b | 6.56 ± 0.01 ab |

| 1000 g | 1.24 ± 0.04 c | 73.33 ± 0.04 b | 77.08 ± 0.12 a | 3.99 ± 0.08 b | 30.78 ± 0.09 a | 3.97 ± 0.17 c | 6.53 ± 0.01 b |

| 1500 g | 1.40 ± 0.05 b | 73.17 ± 0.05 b | 76.95 ± 0.08 a | 3.91 ± 0.10 b | 30.92 ± 0.09 a | 4.12 ± 0.16 b | 6.55 ± 0.01 ab |

| 2000 g | 1.56 ± 0.05 b | 73.01 ± 0.05 b | 76.77 ± 0.07 a | 3.84 ± 0.10 b | 31.08 ± 0.10 a | 4.30 ± 0.16 b | 6.59 ± 0.01 ab |

| 2500 g | 2.12 ± 0.06 a | 72.44 ± 0.06 b | 75.43 ± 0.10 b | 3.65 ± 0.08 c | 32.33 ± 0.11 a | 5.82 ± 0.17 a | 6.63 ± 0.01 a |

| Loading Weight/State | Hardness (gf) | Springiness | Adhesiveness (g·s) | Cohesiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh sample | 2416.8 ± 151.1 a | 0.73 ± 0.02 a | 6.84 ± 0.38 b | 0.36 ± 0.03 a |

| 500 g | 2143.2 ± 165.8 ab | 0.67 ± 0.04 abc | 7.89 ± 0.30 a | 0.30 ± 0.04 ab |

| 1000 g | 2290.6 ± 154.7 ab | 0.70 ± 0.03 ab | 7.78 ± 0.24 a | 0.31 ± 0.02 ab |

| 1500 g | 2178.9 ± 135.2 ab | 0.69 ± 0.02 ab | 7.86 ± 0.21 a | 0.29 ± 0.02 ab |

| 2000 g | 2013.8 ± 152.0 b | 0.65 ± 0.03 bc | 7.93 ± 0.29 a | 0.28 ± 0.05 b |

| 2500 g | 1752.1 ± 132.9 c | 0.61 ± 0.04 c | 8.05 ± 0.36 a | 0.26 ± 0.05 b |

| Placement Form | Sample Size | Dx | Dy | DF-R | DS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 70 mm × 190 mm | 250 mm | 10 mm | 105 mm | - |

| B | 70 mm × 190 mm | 24 mm | - | 124 mm | 162 mm |

| C | 70 mm × 190 mm | 100 mm | 10 mm | 180 mm | - |

| D | 70 mm × 190 mm | 24 mm | - | 124 mm | - |

| E | 70 mm × 190 mm | 0 | 0 | 230 mm | - |

| Placement Form | Thawing Time (min) | Thawing Rate (cm/h) | TCOV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 91.08 ± 1.17 b | 3.30 ± 0.02 a | 3.98 ± 0.26 c |

| B | 91.75 ± 1.22 b | 3.26 ± 0.01 a | 3.78 ± 0.23 c |

| C | 96.25 ± 1.19 a | 3.20 ± 0.01 b | 4.42 ± 0.25 bc |

| D | 97.42 ± 1.18 a | 3.03 ± 0.02 c | 5.80 ± 0.27 b |

| E | 99.08 ± 1.24 a | 2.97 ± 0.02 c | 7.08 ± 0.28 a |

| Placement Form/State | Thawing Loss | pH | L | a | b | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh sample | - | 6.51 ± 0.01 a | 77.20 ± 0.11 a | 4.49 ± 0.09 a | 26.85 ± 0.10 b | - |

| A | 1.04 ± 0.04 c | 6.52 ± 0.01 a | 77.16 ± 0.11 a | 4.19 ± 0.08 ab | 30.06 ± 0.08 a | 3.23 ± 0.16 c |

| B | 0.98 ± 0.04 c | 6.52 ± 0.01 a | 77.18 ± 0.11 a | 4.23 ± 0.09 ab | 29.83 ± 0.08 a | 3.00 ± 0.16 c |

| C | 1.24 ± 0.04 b | 6.53 ± 0.01 a | 77.08 ± 0.12 a | 3.99 ± 0.08 b | 30.78 ± 0.09 a | 3.97 ± 0.17 b |

| D | 1.42 ± 0.05 b | 6.54 ± 0.01 a | 76.97 ± 0.13 a | 3.84 ± 0.10 c | 31.25 ± 0.11 a | 4.46 ± 0.20 b |

| E | 1.75 ± 0.06 a | 6.56 ± 0.01 a | 76.88 ± 0.15 a | 3.65 ± 0.10 d | 32.64 ± 0.13 a | 5.86 ± 0.22 a |

| Placement form/State | Moisture content (%) | Total SEC (MJ/kg) | Hardness (gf) | Springiness | Cohesiveness | Adhesiveness (g·s) |

| Fresh sample | 74.57 ± 0.05 a | - | 2416.8 ± 151.1 a | 0.73 ± 0.02 a | 0.36 ± 0.03 a | 6.84 ± 0.38 c |

| A | 73.53 ± 0.04 b | 2.171 ± 0.136 a | 2380.3 ± 162.6 a | 0.71 ± 0.02 ab | 0.31 ± 0.02 b | 7.76 ± 0.33 b |

| B | 73.59 ± 0.04 b | 2.185 ± 0.127 a | 2393.9 ± 155.2 a | 0.72 ± 0.02 a | 0.32 ± 0.01 b | 7.74 ± 0.22 b |

| C | 73.33 ± 0.04 b | 2.243 ± 0.159 a | 2290.6 ± 154.7 a | 0.70 ± 0.03 ab | 0.31 ± 0.02 b | 7.78 ± 0.24 b |

| D | 73.15 ± 0.05 b | 2.257 ± 0.167 a | 1875.7 ± 156.7 b | 0.68 ± 0.03 ab | 0.29 ± 0.03 b | 7.81 ± 0.24 a |

| E | 72.82 ± 0.06 b | 2.272 ± 0.174 a | 1758.9 ± 153.3 b | 0.66 ± 0.04 b | 0.26 ± 0.04 c | 7.87 ± 0.22 a |

| Thawing Method/State | Thawing Time (min) | Thawing Rate (cm/h) | TCOV (%) | Thawing Loss (%) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh sample | - | - | - | - | 6.51 ± 0.01 c |

| VSRT (OC 1) | 91.75 ± 1.22 c | 3.26 ± 0.01 a | 3.78 ± 0.23 c | 0.98 ± 0.04 c | 6.52 ± 0.01 c |

| VSRT (OC 2) | 135.67 ± 1.24 b | 2.82 ± 0.02 b | 9.8 ± 0.39 b | 1.56 ± 0.05 bc | 6.59 ± 0.01 c |

| AT (OC 1) | 266.67 ± 1.78 a | 0.63 ± 0.04 c | 9.31 ± 0.49 b | 9.03 ± 0.07 a | 6.97 ± 0.01 a |

| AT (OC 2) | 271.25 ± 1.93 a | 0.57 ± 0.03 c | 17.25 ± 0.47 a | 9.32 ± 0.08 a | 6.99 ± 0.01 a |

| VST (OC 1) | 102.25 ± 1.33 c | 2.67 ± 0.02 b | 6.33 ± 0.35 bc | 2.72 ± 0.06 b | 6.64 ± 0.01 bc |

| VST (OC 2) | 151.75 ± 1.38 b | 2.51 ± 0.03 b | 13.55 ± 0.43 ab | 3.38 ± 0.06 b | 6.73 ± 0.01 b |

| Thawing method/State | L | a | b | ΔE | Total SEC (MJ/kg) |

| Fresh sample | 77.20 ± 0.11 a | 4.49 ± 0.09 a | 26.85 ± 0.10 c | - | - |

| VSRT (OC 1) | 77.18 ± 0.11 a | 4.23 ± 0.09 a | 29.83 ± 0.08 bc | 3.00 ± 0.16 c | 2.185 ± 0.127 b |

| VSRT (OC 2) | 76.77 ± 0.07 a | 3.84 ± 0.10 b | 31.08 ± 0.10 b | 4.30 ± 0.16 bc | 1.255 ± 0.179 bc |

| AT (OC 1) | 67.35 ± 0.11 c | 1.83 ± 0.12 d | 38.73 ± 0.10 a | 15.67 ± 0.19 a | 0 c |

| AT (OC 2) | 66.91 ± 0.12 c | 1.66 ± 0.10 d | 39.43 ± 0.12 a | 16.50 ± 0.19 a | 0 c |

| VST (OC 1) | 75.78 ± 0.09 ab | 3.37 ± 0.11 b | 30.89 ± 0.10 b | 4.43 ± 0.17 bc | 9.169 ± 0.156 a |

| VST (OC 2) | 73.21 ± 0.12 b | 3.15 ± 0.08 c | 31.75 ± 0.11 b | 6.46 ± 0.18 b | 6.793 ± 0.183 ab |

| Thawing method/State | Moisture content (%) | Hardness (gf) | Springiness | Cohesiveness | Adhesiveness (g·s) |

| Fresh sample | 74.57 ± 0.05 a | 2416.8 ± 151.1 a | 0.73 ± 0.02 a | 0.36 ± 0.03 a | 6.84 ± 0.38 c |

| VSRT (OC 1) | 73.59 ± 0.04 b | 2393.9 ± 155.2 a | 0.72 ± 0.02 a | 0.32 ± 0.01 a | 7.74 ± 0.22 ab |

| VSRT (OC 2) | 73.01 ± 0.05 c | 2013.8 ± 152.0 bc | 0.65 ± 0.03 ab | 0.28 ± 0.05 b | 7.93 ± 0.29 a |

| AT (OC 1) | 65.54 ± 0.07 e | 1851.4 ± 158.9 d | 0.55 ± 0.05 bc | 0.23 ± 0.03 d | 7.47 ± 0.21 d |

| AT (OC 2) | 65.25 ± 0.08 e | 1791.8 ± 161.7 d | 0.51 ± 0.04 c | 0.22 ± 0.05 d | 7.64 ± 0.25 b |

| VST (OC 1) | 71.85 ± 0.06 d | 2274.1 ± 160.7 b | 0.64 ± 0.03 ab | 0.29 ± 0.02 b | 7.52 ± 0.31 c |

| VST (OC 2) | 71.19 ± 0.06 d | 1955.5 ± 178.1 c | 0.61 ± 0.03 abc | 0.25 ± 0.06 c | 7.71 ± 0.33 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, S.; Xu, N.; Liu, F.; Xue, A. Experimental Study on the Influence of Different Loading Weights and Placement Forms on Vacuum Sublimation–Rehydration Thawing of Large Yellow Croaker. Foods 2026, 15, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030467

Sun Y, Wu W, Chen S, Xu N, Liu F, Xue A. Experimental Study on the Influence of Different Loading Weights and Placement Forms on Vacuum Sublimation–Rehydration Thawing of Large Yellow Croaker. Foods. 2026; 15(3):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030467

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yuyao, Weidong Wu, Shanshan Chen, Nating Xu, Fangran Liu, and Anyuan Xue. 2026. "Experimental Study on the Influence of Different Loading Weights and Placement Forms on Vacuum Sublimation–Rehydration Thawing of Large Yellow Croaker" Foods 15, no. 3: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030467

APA StyleSun, Y., Wu, W., Chen, S., Xu, N., Liu, F., & Xue, A. (2026). Experimental Study on the Influence of Different Loading Weights and Placement Forms on Vacuum Sublimation–Rehydration Thawing of Large Yellow Croaker. Foods, 15(3), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030467