Method of Characterization and Classification of the Physicochemical Quality of Polished White Rice Grains Using VIS/NIR/SWIR Techniques and Machine Learning Models for Lot Segregation and Commercialization in Storage and Processing Units

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Characterization

2.2. Conventional Physical Analysis

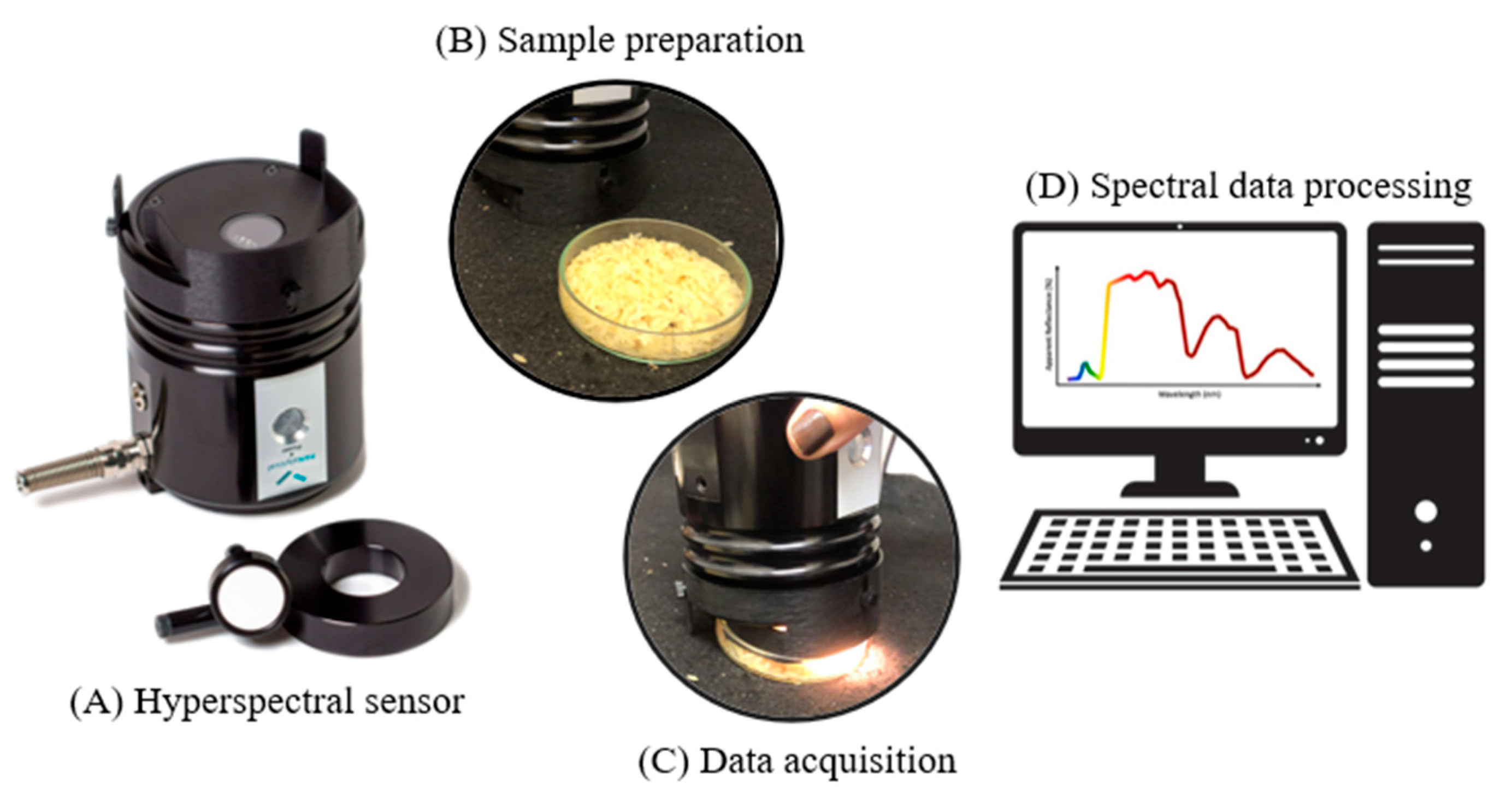

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Indirect Physicochemical Analysis

Statistical and Multivariate Analysis of Physicochemical Parameters

2.5. Hyperspectral Data Collection

2.6. Analysis of Spectral Behavior

2.7. Machine Learning for Classification

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Characterization of White Polished Rice

3.2. Commercial Batches

3.3. Spectral Behavior of Commercial Batches of Polished White Rice

3.4. Classification of Commercial Batches of Polished White Rice Using Machine Learning

3.5. Limitations and Future Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prom-U-Thai, C.; Rerkasem, B. Rice quality improvement. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Coradi, P.C.; Nunes, M.T.; Grohs, M.; Bressiani, J.; Teodoro, P.E.; Anschau, K.F.; Flores, E.M.M. Effects of cultivars and fertilization levels on the quality of rice milling: A diagnosis using near-infrared spectroscopy, x-ray diffraction, and scanning electron microscopy. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilhalva, N.S.; Coradi, P.C.; Moraes, R.S.; Santana, D.C.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Teodoro, P.E.; Leal, M.M. Physical and Physicochemical Classification of Parboiled Rice Using VNIR-SWIR Spectroscopy and Machine Learning. Rice Sci. 2025, 32, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.M.; Bilhalva, N.S.; Moraes, R.S.; Coradi, P.C. Physical Classification of Soybean Grains Based on Physicochemical Characterization Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Agriengineering 2025, 7, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, R.S.; Bilhalva, N.S.; Leal, M.M.; Lemos, A.B.; Coradi, P.C. Application of near-infrared spectroscopy for physicochemical characterization of soft and flint corn grains in pre-processing, storage and industrial unit as alternative to the subjective physical classification method. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 114, 102717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, L.O.; Coradi, P.C.; Rodrigues, D.M.; Lima, R.E.; Teodoro, L.P.T.; Moraes, R.S.; Teodoro, P.E.; Nunes, M.T.; Leal, M.M.; Lopes, L.R. Characterizing and Predicting the Quality of Milled Rice Grains Using Machine Learning Models. Agriengineering 2023, 5, 1196–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mesery, H.S.; Mao, H.; Abomohra, A.E.F. Applications of non-destructive technologies for agricultural and food products quality inspection. Sensors 2019, 19, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squeo, G.; Cruz, J.; Angelis, D.; Caponio, F.; Amigo, J.M. Considerations about the gap between research in near-infrared spectroscopy and official methods and recommendations of analysis in foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2024, 59, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, P.S.; Carbas, B.; Soares, A.; Sousa, I.; Brites, C. Spectral markers and machine learning: Revolutionizing rice evaluation with near infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, M.; Bhardwaj, R.; Singh, P.; Kaur, S.; Singh, S.P.; Dahuja, A.; Krishnan, V.; Kansal, R.; Yadav, V.K.; John, R. From grain to Gain: Bridging conventional methods with chemometric innovations in cereal quality analysis through near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). Food Control 2025, 178, 111482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q. Detection of fraud in high-quality rice by near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, D.L.N.; Nguyen, Q.C.; Marini, F.; Biancolillo, A. Authentication of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Using Near Infrared Spectroscopy Combined with Different Chemometric Classification Strategies. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhao, D.; Pan, K.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Cao, C.; Jiang, Y. Combination of near-infrared spectroscopy and key wavelength-based screening algorithm for rapid determination of rice protein content. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 118, 105216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, L.; Xing, Z.; Dong, D. Infrared microspectroscopy and machine learning: A novel approach to determine the origin and variety of individual rice grains. Agric. Commun. 2024, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Li, Z. Combination of near infrared spectroscopy with characteristic interval selection for rapid detection of rice protein content. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; He, K.; Huang, Y.; Tian, J.; Hu, X.; Liang, Y.; Yi, X.; Xie, L.; Huang, D. The rapid determination of the fatty acid content of rice by combining hyperspectral imaging and integrated learning models. Vib. Spectrosc. 2023, 129, 103609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, Y.; He, L.; Hu, X.; Tian, J.; Chen, M.; Huang, D.; Luo, H. The rapid detection of the tannin content of grains based on hyperspectral imaging technology and chemometrics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 123, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Huang, D.; Yang, B.; Li, J.; Opeyemi, A.T.; Wu, R.; Weng, H.; Cheng, Z. Combining deep convolutional generative adversarial networks with visible-near infrared hyperspectral reflectance to improve prediction accuracy of anthocyanin content in rice seeds. Food Control 2025, 174, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghinezhad, E.; Szumny, A.; Figiel, A.; Amoghin, M.L.; Mirzazadeh, A.; Blasco, J.; Mazurek, S.; Castillo-Gironés, S. The potential application of HSI and VIS/NIR spectroscopy for non-invasive detection of starch gelatinization and head rice yield during parboiling and drying process. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwana, S.; Hazarika, M.K. Application of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy for Rice Characterization Using Machine Learning. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. A 2020, 101, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchbhai, K.G.; Lanjewar, M.G. Detection of amylose content in rice samples with spectral augmentation and advanced machine learning. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznan, A.; Viejo, C.G.; Pang, A.; Fuentes, S. Computer Vision and Machine Learning Analysis of Commercial Rice Grains: A potential digital approach for consumer perception studies. Sensors 2021, 21, 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, P.S.; Almeida, A.S.; Brites, C.M. Use of Artificial Neural Network Model for Rice Quality Prediction Based on Grain Physical Parameters. Foods 2021, 10, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çinar, Í.; Koklu, M. Identification of rice varieties using machine learning algorithms. Tarım Bilim. Derg. 2021, 28, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, N.K.; Subbarao, M.V.; Sethy, P.K.; Behera, S.K.; Panigrahi, G.R. Machine learning with analysis-of-variance-based method for identifying rice varieties. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivamurthaiah, M.M.; Shetra, H.K.K. Non-destructive machine vision system based rice classification usingensemble machine learning algorithms. Recent Adv. Electr. Electron. Eng. (Former. Recent Pat. Electr. Electron. Eng.) 2024, 17, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.O.; Iino, H.; Koyama, K.; Kawamura, S.; Koseki, S.; Lyu, S. Non-destructive quality classification of rice taste properties based on near-infrared spectroscopy and machine learning algorithms. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.F. Sisvar: A computer statistical analysis system. Ciência E Agrotecnologia 2011, 35, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhering, L.L. Rbio: A Tool For Biometric And Statistical Analysis Using The R Platform. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2017, 17, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionel, B.M.; Musabe, R.; Gatera, O.; Twizere, C. A comparative study of machine learning models in predicting crop yield. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, D.C.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Baio, F.H.R.; Santos, R.G.; Coradi, P.C.; Biduski, B.; Silva Junior, C.A.; Teodoro, P.E.; Shiratsuchi, L.S. Classification of soybean genotypes for industrial traits using UAV multispectral imagery and machine learning. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 29, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, H.; Prasad, K.V.; Rajashekhar, C.; Tripathi, D.; Renuka, S.; Shetty, J.; Swamy, K.Y.S. A class imbalance aware hybrid model for accurate rice variety classification. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2025, 6, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstüner, M.; Abdikan, S.; Bilgin, G.; Balik Şanli, F. Hafif Gradyan Artırma Makineleri ile Tarımsal Ürünlerin Sınıflandırılması. Türk Uzak. Algılama Ve CBS Derg. 2020, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Wu, J.; Xu, H.; Xiao, Y.; Xie, H.; Shi, W. The deterioration of starch physiochemical and minerals in high-quality indica rice under low-temperature stress during grain filling. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1295003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CXS 193-1995; General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Food and Feed. Codex Alimentarius Commission: Rome, Italy, 1995.

- Tu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Salah, A.; Xi, M.; Cai, M.; Cheng, B.; Sun, X.; Cao, C.; Wu, W. Variation of rice starch structure and physicochemical properties in response to high natural temperature during the reproductive stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1136347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Tu, D. Effects of Premature Harvesting on Grain Weight and Quality: A field study. Agronomy 2025, 15, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, A.; Qian, L.; Zhang, D. Changes of liposome and antioxidant activity in immature rice during seed development. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Bi, J.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, X.; Wang, P.; Shu, Z. Quality changes in Chinese high-quality indica rice under different storage temperatures with varying initial moisture contents. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1334809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, T.; Gohain, U.P.; Hazarika, J. Effect of Different Processing Methods on the Nutritional Value of Rice. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2021, 9, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Dong, R.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Shen, W. Physicochemical and Morphological Changes in Long-Grain Brown Rice Milling: A study using image visualization technologies. Foods 2024, 13, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.L.; Sousa, I.; Lourenço, V.M.; Sampaio, P.; Gárzon, R.; Rosell, C.M.; Brites, C. Relationship between Physicochemical and Cooking Quality Parameters with Estimated Glycaemic Index of Rice Varieties. Foods 2023, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Qu, J.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, F.; Blennow, A.; Liu, X. Rice starch multi-level structure and functional relationships. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 275, 118777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Sun, L.; Bai, H.; Lu, X.; Fu, Z.; Lv, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, S. Quantitative detection of crude protein in brown rice by near-infrared spectroscopy based on hybrid feature selection. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2024, 247, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Tian, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X.; Xie, L.; Yang, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, D. Detection of the amylose and amylopectin contents of rice by hyperspectral imaging combined with a CNN-AdaBoost model. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Yan, Y.; Ji, X.; Kong, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Peng, T. Transcriptome and Metabolome Analyses Reveals the Pathway and Metabolites of Grain Quality Under Phytochrome B in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 2022, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuili, W.; Wen, G.; Peisong, H.; Xiangjin, W.; Shaoqing, T.; Guiai, J. Differences of Physicochemical Properties Between Chalky and Translucent Parts of Rice Grains. Rice Sci. 2022, 29, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhang, B.; Tan, C.P.; Fu, X.; Huang, Q. Effects of limited moisture content and storing temperature on retrogradation of rice starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, K.T.; Shozib, H.B.; Islam, M.H.; Sarwar, S.; Islam, M.M.; Akanda, M.R.; Siddiquee, M.A.; Mohiduzzaman, M.; Rahim, A.T.M.A.; Shaheen, N. Variations in the Major Nutrient Composition of Dominant High-Yield Varieties (HYVs) in Parboiled and Polished Rice of Bangladesh. Foods 2023, 12, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Majhi, A.; Phagna, K.; Meena, M.K.; Ram, H. Negative regulators of grain yield and mineral contents in rice: Potential targets for crispr-cas9-mediated genome editing. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chang, K.; Yin, J.; Jin, Y.; Yi, X.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Yang, Q.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X. Study on Optimization of Rice-Drying Process Parameters and Directional Regulation of Nutrient Quality. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Xu, Z.; Fan, S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, P.; Xia, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y. Rapid evaluation method of eating quality based on near-infrared spectroscopy for composition and physicochemical properties analysis of rice grains. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hao, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ouyang, J. Influence of moisture and amylose on the physicochemical properties of rice starch during heat treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 168, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, G.; Jia, H.; Shao, Y.; Shi, C. Protein content prediction of rice grains based on hyperspectral imaging. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 320, 124589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Jin, C.; Yin, X. Development of simplified models for nondestructive testing of rice (with husk) protein content using hyperspectral imaging technology. Vib. Spectrosc. 2021, 114, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Mishra, H.N. Detection of insect damaged rice grains using visible and near infrared hyperspectral imaging technique. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2022, 221, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, N.; Qin, Z.; Du, L.; Zhai, X.; Shen, T.; Zhang, R.; Zou, X. Advances in Hyperspectral Imaging Technology for Grain Quality and Safety Detection: A review. Foods 2025, 14, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaby, J.Y.; Huggins, T.D.; Lee, H.; Mcclung, A.M.; Pinson, S.R.M.; Oh, M.; Bauchan, G.R.; Tarpley, L.; Lee, K.; Kim, M.S. Vis/NIR hyperspectral imaging distinguishes sub-population, production environment, and physicochemical grain properties in rice. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Wang, W.; Gao, M.; Feng, X.; Zhang, S.; QIAN, C. Rapid classification of rice according to storage duration via near-infrared spectroscopy and machine learning. Talanta Open 2024, 10, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, S.; Sutar, P.P. Spectral selective infrared heating of food componentes based on optical characteristics and penetration depth: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 10749–10771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Tang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhu, R.; Wang, C.; Sha, W.; Zheng, L.; Huang, L.; Liang, D.; Hu, Y. Detection of amylase activity and moisture content in rice by reflectance spectroscopy combined with spectral data transformation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 290, 122311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazoki, A.; Farokhi, F.; Pazoki, Z. Classification of rice grain varieties using two artificial neural networks MLP and neuro-fuzzy. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2014, 24, 336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, D. Rapid and nondestructive identification of rice storage year using hyperspectral technology. Food Control 2025, 168, 110850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcioni, R.; Antunes, W.C.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Nanni, M.R. Reflectance Spectroscopy for the Classification and Prediction of Pigments in Agronomic Crops. Plants 2023, 12, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acronym | Models | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| RF | Random Forest | [6] |

| GB | Gradient Boosting | [30] |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine | [31] |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors | [3] |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron | [23] |

| XBG | Xtreme Gradient Boosting | [32] |

| LGB | Light Gradient Boosting Machine | [33] |

| CAT | Categorical Boosting | [34] |

| LR | Logistic Regressor | [24] |

| Model | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| CAT | depth = 6; learning_rate = 0.05; n_estimators = 800; random_seed = 42 |

| GB | n_estimators = 200; learning_rate = 0.1; max_depth = 4; random_state = 42 |

| KNN | n_neighbors = 7; weights = “distance” |

| LGBM | n_estimators = 800; learning_rate = 0.05; num_leaves = 31; subsample = 0.8; colsample_bytree = 0.8; random_state = 42 |

| LR | solver = “lbfgs”; multi_class = “multinomial”; class_weight = “balanced”; max_iter = 5000; random_state = 42 |

| MLP | hidden_layer_sizes = (128, 64); activation = “relu”; solver = “adam”; max_iter = 5000; random_state = 42 |

| RF | n_estimators = 200; class_weight = “balanced”; random_state = 42; n_jobs = −1 |

| SVM | kernel = “rbf”; C = 10; probability = True; class_weight = “balanced”; random_state = 42 |

| XGB | n_estimators = 500; max_depth = 6; learning_rate = 0.05; subsample = 0.8; colsample_bytree = 0.8; reg_lambda = 1.0; random_state = 42 |

| Sample | Moisture | Starch | Protein | Lipids | Fiber | Ash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Healthy grains | 12.71 a | 66.64 a | 9.46 e | 2.21 c | 1.24 h | 1.34 d |

| Broken | 12.73 a | 66.65 a | 8.77 g | 2.17 d | 1.29 g | 1.38 d |

| Burnt | 12.57 b | 60.95 e | 10.29 b | 2.12 d | 2.10 a | 1.81 a |

| Pitted or spotted | 12.74 a | 63.67 c | 9.99 c | 2.25 c | 1.89 b | 1.58 b |

| Streaked | 12.53 b | 65.38 b | 9.08 f | 2.13 d | 1.61 d | 1.51 c |

| Green | 12.01 d | 61.32 d | 12.57 a | 2.74 b | 1.71 c | 1.79 a |

| Yellow | 12.59 b | 63.66 b | 9.91 c | 2.82 a | 1.35 f | 1.56 b |

| Chalky | 12.27 c | 65.56 b | 9.71 d | 2.22 c | 1.47 e | 1.54 b |

| Pr>Fc | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| CV (%) | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.54 | 1.35 | 1.51 | 1.38 |

| SD (%) | 0.24 | 2.12 | 1.11 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.16 |

| Shapiro–Wilk (p) | 0.226 | 0.145 | 0.641 | 0.055 | 0.536 | 0.883 |

| Levene (p) | 0.948 | 0.873 | 0.641 | 0.922 | 0.678 | 0.727 |

| Average | 12.52 | 64.23 | 9.97 | 2.33 | 1.58 | 1.56 |

| Sample | Moisture | Starch | Protein | Lipids | Fiber | Ash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Type 1 | 11.13 d | 73.39 a | 8.05 c | 1.55 c | 2.10 a | 1.12 c |

| Type 2 | 11.84 c | 71.65 b | 8.84 b | 1.43 d | 2.04 b | 1.18 a |

| Type 3 | 12.43 b | 70.54 c | 9.31 a | 1.45 d | 1.98 c | 1.19 a |

| Type 4 | 12.50 b | 70.09 d | 9.47 a | 1.45 d | 1.92 d | 1.18 a |

| Type 5 | 13.06 a | 69.24 e | 9.57 a | 1.61 b | 1.86 e | 1.16 b |

| Off-Type | 12.40 b | 70.92 c | 8.63 b | 1.71 a | 1.99 c | 1.18 a |

| Pr>Fc | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| CV (%) | 6.81 | 1.95 | 9.81 | 13.70 | 5.88 | 4.26 |

| SD (%) | 1.03 | 1.90 | 1.02 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Shapiro–Wilk (p) | 0.787 | 0.758 | 0.827 | 0.545 | 0.040 | 0.000 |

| Levene (p) | 0.951 | 0.695 | 0.729 | 0.863 | 0.701 | 0.136 |

| Average | 12.23 | 70.97 | 8.98 | 1.53 | 1.98 | 1.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Carneiro, L.d.O.; Bilhalva, N.d.S.; Manfroi Filho, Ê.A.; Santana, D.C.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Teodoro, P.E.; Coradi, P.C. Method of Characterization and Classification of the Physicochemical Quality of Polished White Rice Grains Using VIS/NIR/SWIR Techniques and Machine Learning Models for Lot Segregation and Commercialization in Storage and Processing Units. Foods 2026, 15, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010062

Carneiro LdO, Bilhalva NdS, Manfroi Filho ÊA, Santana DC, Teodoro LPR, Teodoro PE, Coradi PC. Method of Characterization and Classification of the Physicochemical Quality of Polished White Rice Grains Using VIS/NIR/SWIR Techniques and Machine Learning Models for Lot Segregation and Commercialization in Storage and Processing Units. Foods. 2026; 15(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarneiro, Letícia de Oliveira, Nairiane dos Santos Bilhalva, Ênio Antônio Manfroi Filho, Dthenifer Cordeiro Santana, Larissa Pereira Ribeiro Teodoro, Paulo Eduardo Teodoro, and Paulo Carteri Coradi. 2026. "Method of Characterization and Classification of the Physicochemical Quality of Polished White Rice Grains Using VIS/NIR/SWIR Techniques and Machine Learning Models for Lot Segregation and Commercialization in Storage and Processing Units" Foods 15, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010062

APA StyleCarneiro, L. d. O., Bilhalva, N. d. S., Manfroi Filho, Ê. A., Santana, D. C., Teodoro, L. P. R., Teodoro, P. E., & Coradi, P. C. (2026). Method of Characterization and Classification of the Physicochemical Quality of Polished White Rice Grains Using VIS/NIR/SWIR Techniques and Machine Learning Models for Lot Segregation and Commercialization in Storage and Processing Units. Foods, 15(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010062