Exploring the Effects of High Protein and High Inulin Composite Shrimp Surimi Gels on Constipated Mice by Modulating Gastrointestinal Function and Gut Microbiota

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Preparation of Composite Shrimp Surimi Gels

2.3. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

2.4. IDDSI Test

2.5. Animal Experiment

2.6. Fecal Indicators

2.6.1. Determination of Fecal Water Content

2.6.2. Determination of the Time of First Black Feces and Number of Fecal Pellets

2.7. Indicators of Gastrointestinal Motility

2.7.1. Small Intestine Advancement Rate

2.7.2. Gastric Emptying Rate

2.8. Intestinal Fluorescence Imaging

2.9. Histopathological Examination

2.10. Enteric Neurotransmitter Assay

2.11. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single Factor Test

3.2. Response Surface Optimization Experiment and IDDSI Test

3.3. Effect of Dietary Intervention on the Body Weight and Fecal Indicators of Constipated Mice

3.4. Effects of Dietary Intervention on the Gastrointestinal Motility Indicators of Constipated Mice

3.5. Effect of Dietary Intervention on the Intestinal Fluorescence Image and Histopathology of Constipated Mice

3.6. Effect of Dietary Intervention on the Intestinal Neurotransmitters of Constipated Mice

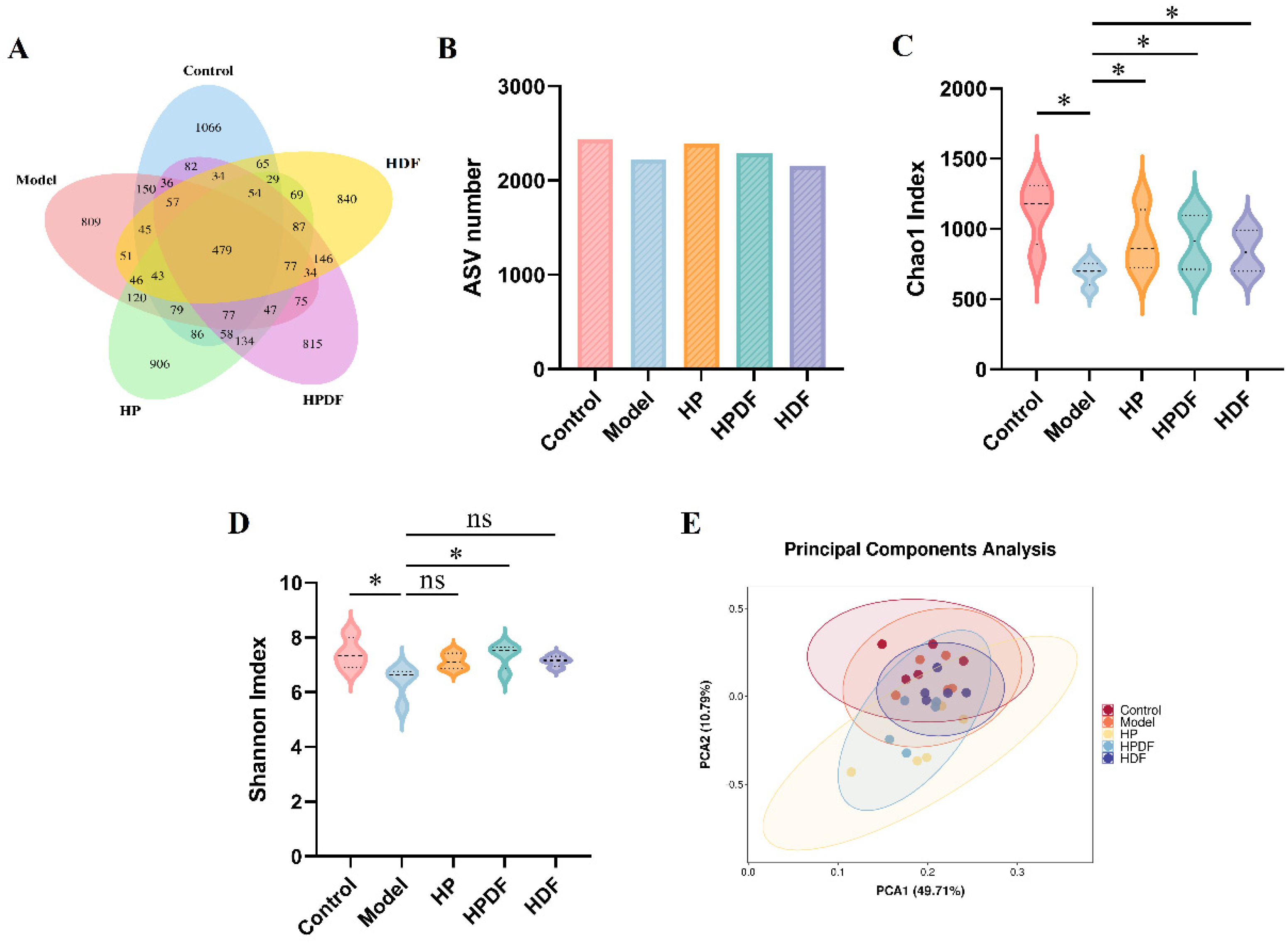

3.7. Effect of Dietary Intervention on Diversity of Gut Microbiota in Constipated Mice

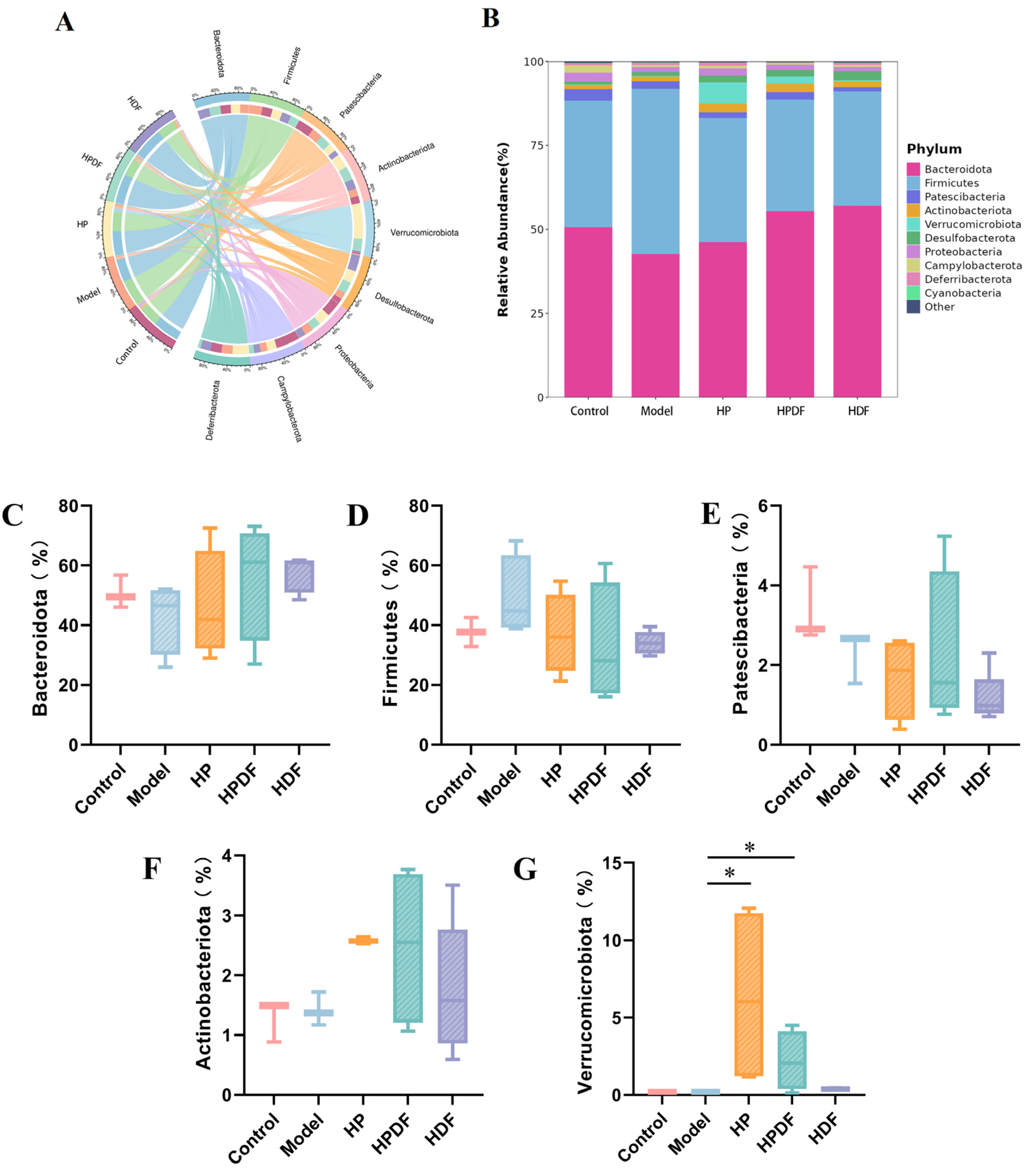

3.8. Effect of Dietary Intervention on the Abundance of Gut Microbiota at Phylum Level in Constipated Mice

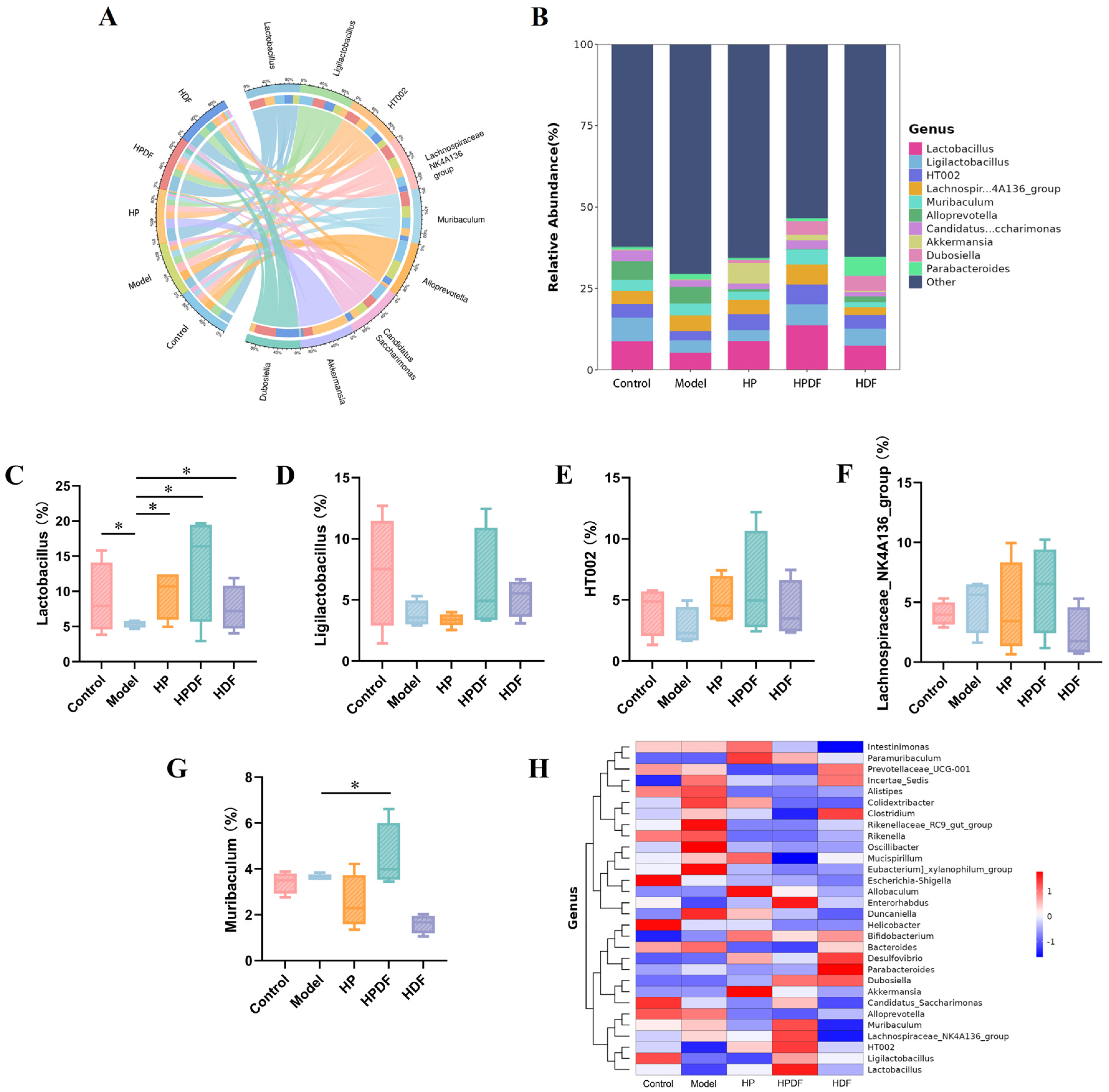

3.9. Effect of Dietary Intervention on the Abundance of Gut Microbiota at Genus Level in Constipated Mice

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, X.; Liu, S.; Jia, P.; Wang, X.; Gan, J.; Hu, W.; Zhu, H.; Song, Y.; Niu, J.; Ji, Y. Epidemiology of Constipation in Elderly People in Parts of China: A Multicenter Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 823987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppen, I.J.N.; Vriesman, M.H.; Saps, M.; Rajindrajith, S.; Shi, X.; van Etten-Jamaludin, F.S.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Benninga, M.A.; Tabbers, M.M. Prevalence of functional defecation disorders in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018, 198, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, G.; Cao, G.; Yang, C. Effects of inulin and isomalto-oligosaccharide on diphenoxylate-induced constipation, gastrointestinal motility-related hormones, short-chain fatty acids, and the intestinal flora in rats. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9216–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.O.; Hui, W.M.; Lam, K.F.; Leung, G.; Yuen, M.F.; Lam, S.K.; Wong, B.C. Familial aggregation in constipated subjects in a tertiary referral center. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.; Whitehead, W.E.; Palsson, O.S.; Törnblom, H.; Simrén, M. An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 14, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Shen, H.; Chen, X.; Li, G. Gender differences in the association between dietary protein intake and constipation: Findings from NHANES. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1393596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Quan, L. Association between dietary phosphorus intake and chronic constipation in adults: Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yang, J.; Ruan, Z.; Wang, Z. Fermentation of dietary fibers modified by an enzymatic- ultrasonic treatment and evaluation of their impact on gut microbiota in mice. J. Food Process. Pres. 2021, 45, e15337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Chen, M.; Niu, J.; Qu, N.; Ji, B.; Duan, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B. The Manufacturing Process of Kiwifruit Fruit Powder with High Dietary Fiber and Its Laxative Effect. Molecules 2019, 24, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, N.; Sun, G.; Bao, X.; Lin, A.; Liu, H. Chitosan oligosaccharides attenuate loperamide-induced constipation through regulation of gut microbiota in mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Dong, J.; Jiang, S.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Kang, W. Effect of Durio zibethinus rind polysaccharide on functional constipation and intestinal microbiota in rats. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa-Kozak, U.; Wiątecka, D.; Bączek, N.; Brzóska, M.M. Inulin and fructooligosaccharide affect in vitro calcium uptake and absorption from calcium-enriched gluten-free bread. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamm, G.; Glinsmann, W.; Kritchevsky, D.; Prosky, L.; Roberfroid, M. Inulin and Oligofructose as Dietary Fiber: A Review of the Evidence. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2001, 41, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illippangama, A.U.; Jayasena, D.D.; Jo, C.; Mudannayake, D.C. Inulin as a functional ingredient and their applications in meat products. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 275, 118706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Tao, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, S.; Hong, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Qian, H.; Zha, Z. Ternary inulin hydrogel with long-term intestinal retention for simultaneously reversing IBD and its fibrotic complication. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeny, T.E.; Essa, R.Y.; Bisar, B.A.; Metwalli, S.M. Effect of using chicory roots powder as a fat replacer on beef burger quality. Slov. Vet. Res. 2019, 56, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wu, Y.; Cao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xiang, H.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y. Preparation and characterization of fish-derived protein gel as a potential dysphagia food: Co-mingling effects of inulin and konjac glucomannan mixtures. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Liu, B.; Liu, Z.; Qi, T. Effects of different drying methods on the structures and functional properties of phosphorylated Antarctic krill protein. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 3690–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, P.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D. Impact of L-arginine on the quality of heat-treated Antarctic krill: Influence of pH and the guanidinium group. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tou, J.C.; Jaczynski, J.; Chen, Y. Krill for Human Consumption: Nutritional Value and Potential Health Benefits. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Lin, J.; Ren, X.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, D. Effect of Heating on Protein Denaturation, Water State, Microstructure, and Textural Properties of Antarctic Krill (Euphausia superba) Meat. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2022, 15, 2313–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zong, M.; Zhu, J.; Guo, X.; Sun, Z. High-protein high-konjac glucomannan diets changed glucose and lipid metabolism by modulating colonic microflora and bile acid profiles in healthy mouse models. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, H.; Sun, P.; Lin, J.; Ren, X.; Li, D. Based on hydrogen and disulfide-mediated bonds, l-lysine and l-arginine enhanced the gel properties of low-salt mixed shrimp surimi (Antarctic krill and Pacific white shrimp). Food Chem. 2024, 445, 138735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, B. Potential of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) protein as a promising alternative resource for efficient production of surimi: Application and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2025, 157, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Gao, P.; Jiang, Q.; Yu, P.; Yang, F.; Pan, M.; Zhou, X.; Xia, W. Effect of κ-carrageenan on the physicochemical and structural characteristics of ready-to-eat Antarctic Krill surimi gel. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 3711–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fei, W.; Shen, M.; Wen, H.; Chen, F.; Xie, J. Texture, swallowing and digestibility characteristics of a low-GI dysphagia food as affected by addition of dietary fiber and anthocyanins. Food Res. Int. 2024, 197, 115201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Cotter, D.; Hickson, M.; Frost, G. Comparison of energy and protein intakes of older people consuming a texture modified diet with a normal hospital diet. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2005, 18, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Pillidge, C.; Harrison, B.; Xu, C.; Adhikari, B. Development and characterization of protein-rich mixed-protein soft foods for the elderly with swallowing difficulties. Food Chem. 2025, 494, 146225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Sun, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Man, H.; Li, D. A food for elders with dysphagia: Effect of sodium alginate with different viscosities on the gel properties of antarctic krill composite shrimp surimi. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, S.; Jiang, P.; Bao, Z.; Li, S.; Sun, N. Insight into the Gel Properties of Antarctic Krill and Pacific White Shrimp Surimi Gels and the Feasibility of Polysaccharides as Texture Enhancers of Antarctic Krill Surimi Gels. Foods 2022, 11, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.S.; Miles, A.; Braakhuis, A. The Effectiveness of International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative–Tailored Interventions on Staff Knowledge and Texture-Modified Diet Compliance in Aged Care Facilities: A Pre-Post Study. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, c32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Tang, X.; Xu, H.; Tang, S. Maren Pills Improve Constipation via Regulating AQP3 and NF- κ B Signaling Pathway in Slow Transit Constipation In Vitro and In Vivo. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. 2020, 2020, 9837384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Wen, P.; Fu, H.; Lin, G.; Liao, S.; Zou, Y. Protective effect of mulberry (Morus atropurpurea) fruit against diphenoxylate-induced constipationin mice through the modulation of gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xia, X.; Du, M.; Cheng, S.; Zhu, B.; Xu, X. Highly Effective Nobiletin-MPN in Yeast Microcapsules for Targeted Modulation of Oxidative Stress, NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation, and Immune Responses in Ulcerative Colitis. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 13054–13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Hu, M.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, D.; Gao, M.; Xia, J.; Miao, M.; Shi, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. Laxative effect and mechanism of Tiantian Capsule on loperamide-induced constipation in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 266, 113411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logue, J.B.; Stedmon, C.A.; Kellerman, A.M.; Nielsen, N.J.; Andersson, A.F.; Laudon, H.; Lindström, E.S.; Kritzberg, E.S.; Sveriges, L. Experimental insights into the importance of aquatic bacterial community composition to the degradation of dissolved organic matter. ISME J. 2016, 10, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, X.; Lin, J.; Sun, P.; Ren, X.; Xu, W.; Tong, Y.; Li, D. Effect and synergy of different exogenous additives on gel properties of the mixed shrimp surimi (Antarctic krill and White shrimp). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 5338–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Li, Y. A review of inhibition mechanisms of surimi protein hydrolysis by different exogenous additives and their application in improving surimi gel quality. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 140002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Tan, M. Salmon protein gel enhancement for dysphagia diets: Konjac glucomannan and composite emulsions as texture modifiers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.S.; Lim, J.; Moon, K. Effects of isolated pea protein on honeyed red ginseng manufactured by 3D printing for patients with dysphagia. LWT 2024, 191, 115570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgil, D. Dietary Fiber for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 35–59. ISBN 978-0-12-805130-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Chen, D.; Tian, G.; Zheng, P.; Mao, X.; Yua, J.; He, J.; Huang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; et al. Effects of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, intestinal microbe and barrier function in weaning piglet. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 2020, 260, 114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, G.S.; Xiao, C.W.; Cockell, K.A. Impact of antinutritional factors in food proteins on the digestibility of protein and the bioavailability of amino acids and on protein quality. Brit. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S315–S332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, M.; Brown, S.; Chiarioni, G.; Dimidi, E.; Dudding, T.; Emmanuel, A.; Fox, M.; Ford, A.C.; Giordano, P.; Grossi, U.; et al. Chronic constipation in adults: Contemporary perspectives and clinical challenges. 2: Conservative, behavioural, medical and surgical treatment. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Yu, J.; Zhan, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, W. constipation through regulation of intestinal microflora by promoting the colonization of Akkermansia sps. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.W.; Lubowski, D.Z. Slow-transit constipation: Evaluation and treatment. Anz. J. Surg. 2007, 77, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Chen, J.; Miao, S.; Deng, K.; Liu, J.; Zeng, S.; Zheng, B.; Lu, X. Lotus seed oligosaccharides at various dosages with prebiotic activity regulate gut microbiota and relieve constipation in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 134, 110838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhe, S.; Anand, M.; Anal, A.K. Dietary fibers, dietary peptides and dietary essential fatty acids from food processing by-products. In Food Processing by-Products and Their Utilization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; Volume 4, pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Devaraj, R.D.; Reddy, C.K.; Xu, B. Health-promoting effects of konjac glucomannan and its practical applications: A critical review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkman, H.P.; Sharkey, E.; Mccallum, R.W.; Hasler, W.L.; Koch, K.L.; Sarosiek, I.; Abell, T.L.; Kuo, B.; Shulman, R.J.; Grover, M.; et al. Constipation in patients with symptoms of gastroparesis: Analysis of symptoms and gastrointestinal transit. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wei, W.; Zhao, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, J.; Yao, S. Intestinal mucosal barrier in functional constipation: Dose it change? World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, C.H.; Farrugia, G. Gastrointestinal neuromuscular pathology in chronic constipation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 25, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sluis, M.; De Koning, B.A.E.; De Bruijn, A.C.J.M.; Velcich, A.; Meijerink, J.P.P.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Büller, H.A.; Dekker, J.; Van Seuningen, I.; Renes, I.B.; et al. Muc2-Deficient Mice Spontaneously Develop Colitis, Indicating That Muc2 Is Critical for Colonic Protection. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, D.; Whang, C.; Hong, J.; Kim, D.; Prayogo, M.C.; Son, Y.; Jung, W.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Jon, S. Anti-inflammatory glycocalyx-mimicking nanoparticles for colitis treatment: Construction and in vivo evaluation. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202304815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Long, X.; Tan, F.; Zhao, X. Inhibitory Effect of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis HFY14 on Diphenoxylate-Induced Constipation in Mice by Regulating the VIP-cAMP-PKA-AQP3 Signaling Pathway. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W. The Different Ways Multi-Strain Probiotics with Different Ratios of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus Relieve Constipation Induced by Loperamide in Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Yi, R.; Zhao, X. Inhibitory Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum CQPC02 Isolated from Chinese Sichuan Pickles (Paocai) on Constipation in Mice. J. Food Qual. 2019, 15, 9781914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhao, M.; Du, L.; Hou, J.; Dong, J.; Zhang, B. Licorice water extract improves constipation by repairing the intestinal barrier and regulating the gut microbiota: A potential alternative treatment strategy. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodan, A.; Tremaroli, V.; Brolin, H.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Levin, E. Comparing bioinformatic pipelines for microbial 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e227434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthyala, S.D.V.; Shankar, S.; Klemashevich, C.; Blazier, J.C.; Hillhouse, A.; Wu, C. Differential effects of the soluble fib er inulin in reducing adiposity and altering gut microbiome in aging mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 105, 108999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Li, C. Effect and mechanism of functional compound fruit drink on gut microbiota in constipation mice. Food Chem. 2023, 401, 134210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kurata, R.; Tonozuka, T.; Funane, K.; Park, E.Y.; Miyazaki, T. Bacteroidota polysaccharide utilization system for branched dextran exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena, C.; Valdés-Mas, R.; Mayoral, P.; Garabaya, C.; Durand, S.; Rodríguez, F.; Fernández-García, M.T.; Salazar, N.; Nogacka, A.M.; Garatachea, N.; et al. Healthspan and lifespan extension by fecal microbiota transplantation into progeroid mice. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, M.; Fu, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, L. Safflower dietary fiber alleviates functional constipation in rats via regulating gut microbiota and metabolism. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, F.; Yuan, S.; Dai, W.; Yin, L.; Dai, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Guo, Q.; Zhu, Q. Development of novel Lactobacillus plantarum-encapsulated Bigel based on soy lecithin-beeswax oleogel and flaxseed gum hydrogel for enhanced survival during storage and gastrointestinal digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 163, 111052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, T.S. Lactobacillus plantarum isolated from kimchi, a Korean fermented food, attenuates imiquimod-induced psoriasis in mice. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | Weight (g) |

|---|---|

| Antarctic krill | 40 |

| Litopenaeus vannamei | 60 |

| Ice water | 15 |

| NaCl | 1 |

| Soybean oil | 0.5 |

| Monosodium glutamate | 0.5 |

| Inulin | 3 |

| EWP | 3 |

| ADSP | 3 |

| SA | 0.5 |

| Lys | 0.4 |

| Ingredients | Basic Feed (%) | HP (%) | HPDF (%) | HDF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 28.4 | 19.88 | 19.88 | 26.56 |

| Wheat middlings | 28.6 | 20.02 | 20.02 | 26.74 |

| Soybean meal | 16 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 14.96 |

| Flour | 18 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 16.83 |

| Vegetable oil | 1.6 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.5 |

| Calcium bicarbonate | 1.6 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.5 |

| Fishmeal | 1.5 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.4 |

| Additive | 4.3 | 3.01 | 3.01 | 4.02 |

| AKSG without dietary fibre | — | 30 | — | — |

| AKSG | — | — | 30 | — |

| Inulin | — | — | — | 5.5 |

| Sodium alginate | — | — | — | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tan, Y.; Sun, P.; Tao, C.; Qin, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, D. Exploring the Effects of High Protein and High Inulin Composite Shrimp Surimi Gels on Constipated Mice by Modulating Gastrointestinal Function and Gut Microbiota. Foods 2026, 15, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010059

Tan Y, Sun P, Tao C, Qin Y, Liu H, Li D. Exploring the Effects of High Protein and High Inulin Composite Shrimp Surimi Gels on Constipated Mice by Modulating Gastrointestinal Function and Gut Microbiota. Foods. 2026; 15(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Yuting, Peizi Sun, Chen Tao, Yajie Qin, Huimin Liu, and Dongmei Li. 2026. "Exploring the Effects of High Protein and High Inulin Composite Shrimp Surimi Gels on Constipated Mice by Modulating Gastrointestinal Function and Gut Microbiota" Foods 15, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010059

APA StyleTan, Y., Sun, P., Tao, C., Qin, Y., Liu, H., & Li, D. (2026). Exploring the Effects of High Protein and High Inulin Composite Shrimp Surimi Gels on Constipated Mice by Modulating Gastrointestinal Function and Gut Microbiota. Foods, 15(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010059