Vanillin Activates HuTGA1-HuNPR1/5-1 Signaling to Enhance Postharvest Pitaya Resistance to Soft Rot

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pitaya Fruit

2.2. Determination of Fruit Quality Attributes

2.3. Determination of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Level and Defense-Related Enzyme Activities

2.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.5. Gene Cloning and Sequence Analysis

2.6. Subcellular Localization of HuTGA1

2.7. Yeast One-Hybrid Assay (Y1H)

2.8. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.9. Transient Overexpression of HuTGA1 in Pitaya Fruit

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

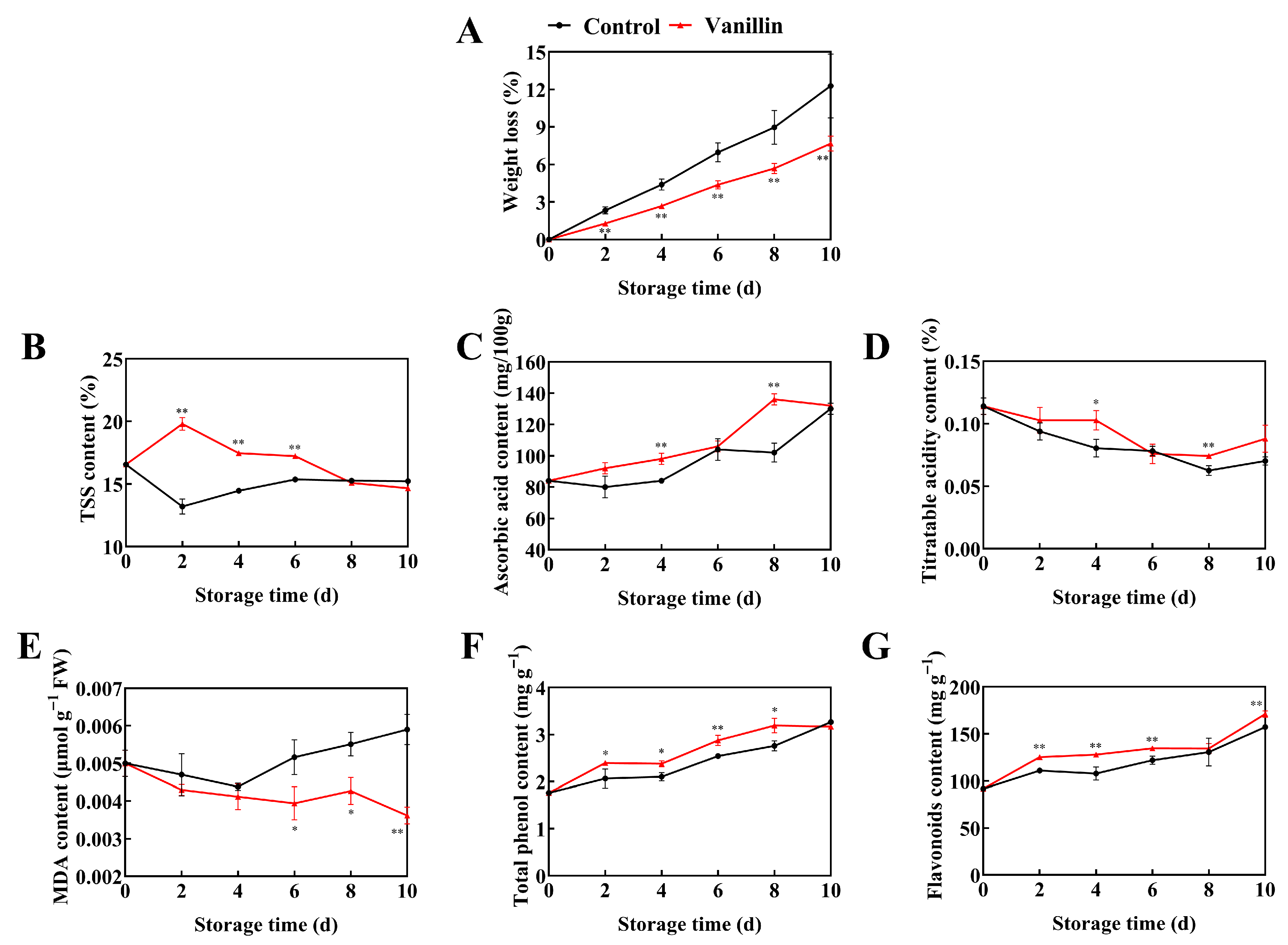

3.1. Vanillin Treatment Enhances Disease Resistance and Maintains the Quality of Pitaya Fruit During Storage

3.2. Vanillin Treatment Regulates Redox Balance and Enhances Defense Enzyme Activities in Pitaya Fruit

3.3. The Expression Patterns of Defense-Related Genes in Pitaya Treated with Vanillin

3.4. Correlation Analysis Between Postharvest Disease Resistance, Antioxidant Traits, and TGA-NPR Interaction

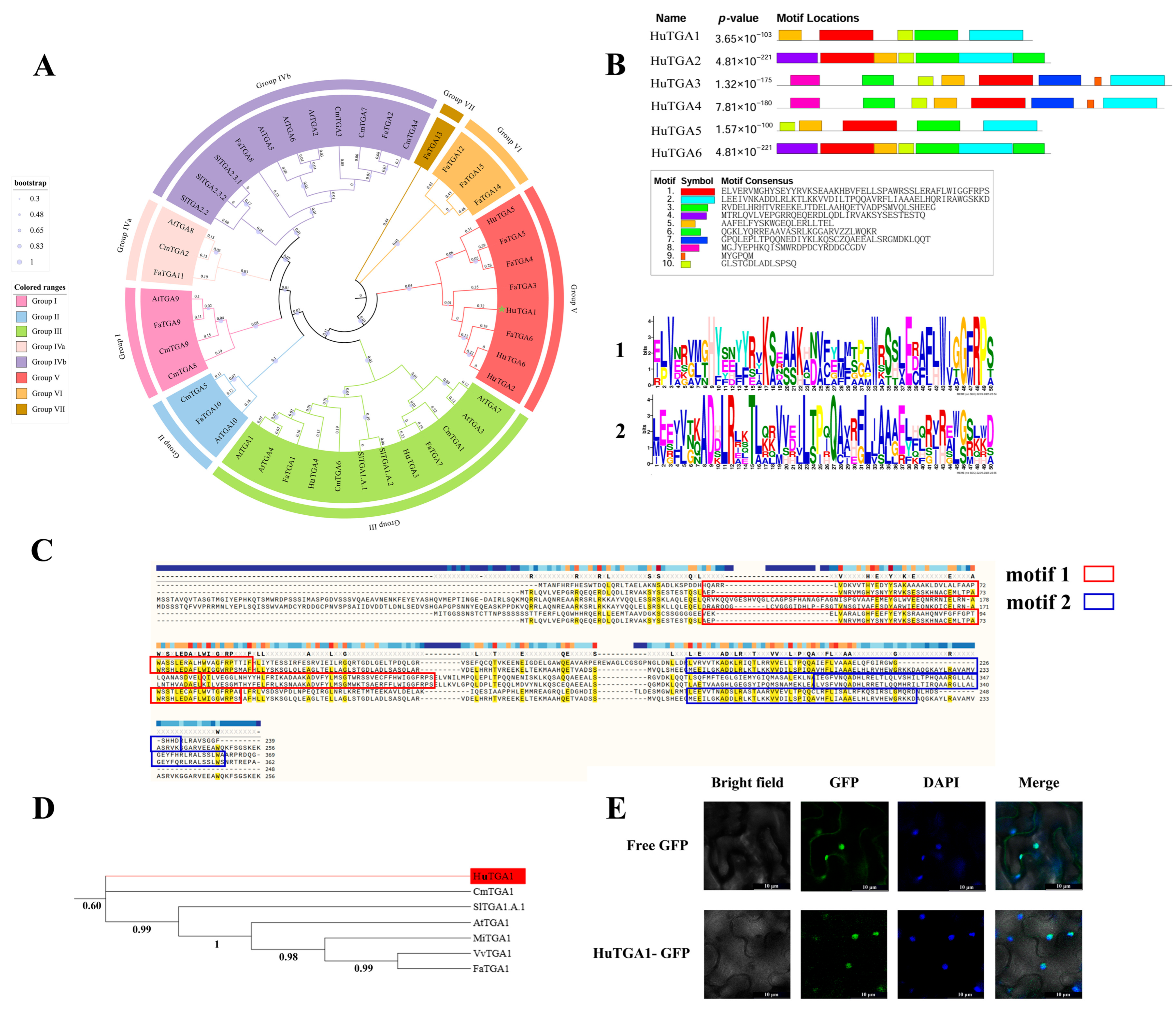

3.5. Phylogenetic, Motif, and Subcellular Localization Analysis of the HuTGA1 Gene

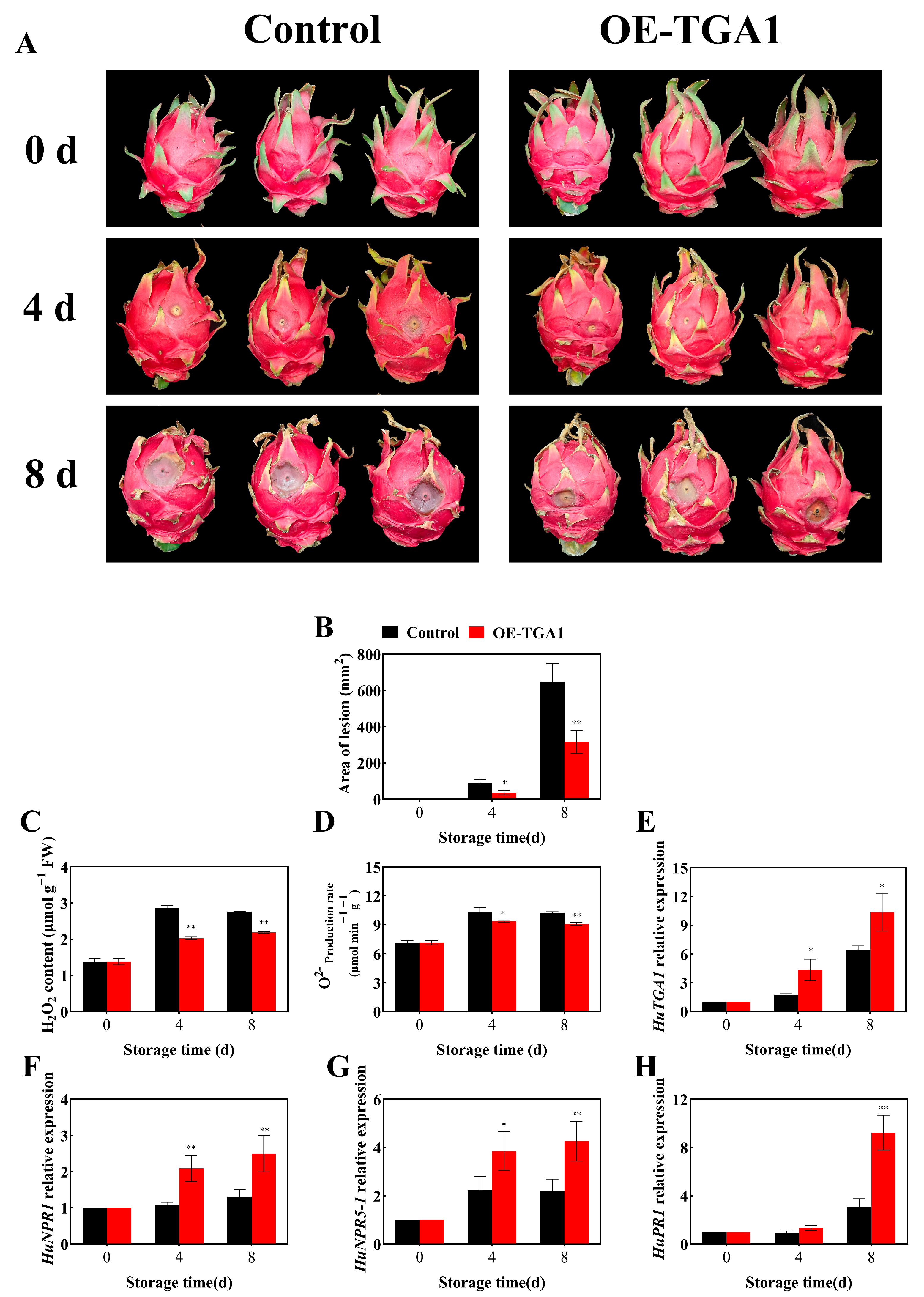

3.6. HuTGA1 Positively Regulates HuNPR Genes to Enhance Disease Resistance in Pitaya Fruit

4. Discussion

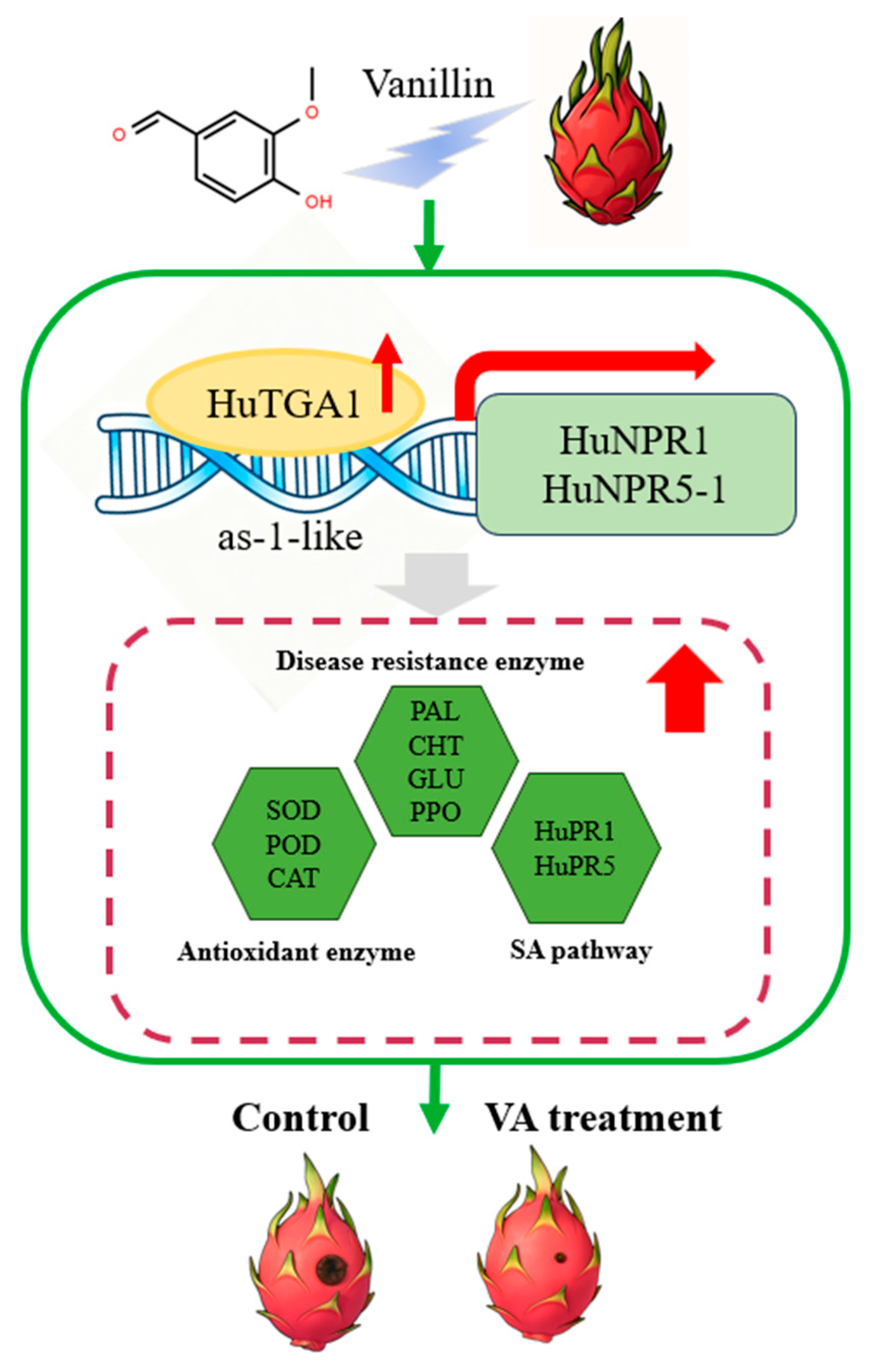

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Du, J.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, S.; Jiang, J. Enhancement of Nutritional and Flavor Properties of Red-Fleshed Pitaya Juice via Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Fermentation. Food Chem. 2025, 30, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, P.C.; Pranta, G.K.; Mojumdar, M.U.; Mahmud, A.; Noori, S.R.H.; Chakraborty, N.R. UDCAD-DFL-DL: A Unique Dataset for Classifying and Detecting Agricultural Diseases in Dragon Fruits and Leaves. Data Brief 2025, 59, 111411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Zahid, N.; Manickam, S.; Siddiqui, Y.; Alderson, P.G.; Maqbool, M. Effectiveness of Submicron Chitosan Dispersions in Controlling Anthracnose and Maintaining Quality of Dragon Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 86, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, G.; Gao, Z.; Li, M.; Su, Z.; Zhang, Z. Inhibition on Anthracnose and Induction of Defense Response by Nitric Oxide in Pitaya Fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 245, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cai, Z.; Ba, L.; Qin, Y.; Su, X.; Luo, D.; Shan, W.; Kuang, J.; Lu, W.; Li, L.; et al. Maintenance of Postharvest Quality and Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis of Pitaya Fruit by Essential Oil P-Anisaldehyde Treatment. Foods 2021, 10, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, W.; Li, F.; Xiao, S.; Duan, X. BTH Treatment Delays the Senescence of Postharvest Pitaya Fruit in Relation to Enhancing Antioxidant System and Phenylpropanoid Pathway. Foods 2021, 10, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.T.D.; Mitcham, E.J. Quality of Pitaya Fruit (Hylocereus undatus) as Influenced by Storage Temperature and Packaging. Sci. Agric. 2013, 70, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Guo, J.; Xu, W.; Ning, X.; Li, X.; He, M.; Liu, Q. Active Chitosan Films Crosslinked by Vanillin-Derived Dialdehyde for Effective Fruit Preservation. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 164, 111147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Zhang, H.; Xue, Y.; Zeng, K. Effects of INA on Postharvest Blue and Green Molds and Anthracnose Decay in Citrus Fruit. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Wang, L.; Zou, Y.; Fu, L.; Han, C.; Li, A.; Li, L.; Zhu, C. Impact of Vanillin on Postharvest Disease Control of Apple. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 979737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Yu-Xuan, W.; Tao, L.; Zhang, Y.-D.; Wang, S.-R.; Zhang, G.-C.; Zhang, J. Inhibitory Effects and Mechanisms of Vanillin on Gray Mold and Black Rot of Cherry Tomatoes. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 175, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, Z.S.; Ding, P.; Nakasha, J.J.; Yusoff, S.F. Controlling Fusarium oxysporum Tomato Fruit Rot under Tropical Condition Using Both Chitosan and Vanillin. Coatings 2021, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsuwan, J.; Sutthasupa, S. Effect of Chitosan and Alginate Beads Incorporated with Lavender, Clove Essential Oils, and Vanillin against Botrytis Cinerea and Their Application in Fresh Table Grapes Packaging System. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2019, 32, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Tan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, F.; Yao, X.; Lin, H.; Zhang, D. Salicylic Acid-activated BIN2 Phosphorylation of TGA3 Promotes Arabidopsis PR Gene Expression and Disease Resistance. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e110682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Dai, Y.; Noman, M.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Song, F.; Li, D. Genome-Wide Characterization and Functional Analysis of the Melon TGA Gene Family in Disease Resistance through Ectopic Overexpression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 212, 108784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Dong, T.; Chen, W.; Zou, N.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Wang, M.; Liu, J. Expression Analysis of MaTGA8 Transcription Factor in Banana and Its Defence Functional Analysis by Overexpression in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.-Y.; Chen, J.; Shi, Y.; Fu, H.-Y.; Huang, M.-T.; Rott, P.C.; Gao, S.-J. Sugarcane Responses to Two Strains of Xanthomonas Albilineans Differing in Pathogenicity through a Differential Modulation of Salicylic Acid and Reactive Oxygen Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1087525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, T.; Yu, R.; Suo, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, G.; Yao, D.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Gao, G. A Genome-Wide Analysis of StTGA Genes Reveals the Critical Role in Enhanced Bacterial Wilt Tolerance in Potato During Ralstonia solanacearum Infection. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 894844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yuan, L.; Yin, X.; Jiang, X.; Wei, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, N.; Liu, Q. The Grapevine Transcription Factor VvTGA8 Enhances Resistance to White Rot via the Salicylic Acid Signaling Pathway in Tomato. Agron. J. 2023, 13, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xi, M.; Liu, T.; Wu, X.; Ju, L.; Wang, D. The Central Role of Transcription Factors in Bridging Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses for Plants’ Resilience. New Crops 2024, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; You, W.; Li, R.; Li, W.; Shao, Y. Construction of the PG-deficient Mutant of Fusarium equiseti by CRISPR/Cas9 and Its Pathogenicity of Pitaya. J. Basic Microbiol. 2021, 61, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Meng, F.; Wei, X.; Lin, M. Postharvest Dipping Treatment with BABA Induced Resistance against Rot Caused by Gilbertella persicaria in Red Pitaya Fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Xu, Q.; Dong, J.; Kebbeh, M.; Shen, S.; Huan, C.; Zheng, X. Effects of Exogenous Melatonin on Ripening and Decay Incidence in Plums (Prunus salicina L. Cv. Taoxingli) during Storage at Room Temperature. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 292, 110655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Sheng, J.; Shen, L. Nitric Oxide Plays an Important Role in β-Aminobutyric Acid-Induced Resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Tomato Plants. Plant Pathol. J. 2020, 36, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Shi, X.; Wei, L.; Li, W.; Shao, Y. Ripening Patterns (off-Tree and on-Tree) Affect Physiology, Quality, and Ascorbic Acid Metabolism of Mango Fruit (Cv. Guifei). Sci. Hortic. 2023, 315, 111971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Peng, D.; Shao, Y.; Li, R.; Li, W. Bacillus siamensis N-1 Improves Fruit Quality and Disease Resistance by Regulating ROS Homeostasis and Defense Enzyme Activities in Pitaya. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 329, 112975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, H.; Lin, H.; Hung, Y.-C.; Xie, H.; Chen, Y. Acidic Electrolyzed Water Treatment Delayed Fruit Disease Development of Harvested Longans through Inducing the Disease Resistance and Maintaining the ROS Metabolism Systems. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 171, 111349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Guo, M.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, S.; Chen, G. Methyl salicylate and methyl jasmonate induce resistance to Alternaria tenuissima by regulating the phenylpropane metabolism pathway of winter jujube. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 204, 112440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Y. Identification of Polysaccharides from Pericarp Tissues of Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) Fruit in Relation to Their Antioxidant Activities. Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z.; Gao, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Qu, H.; Jiang, Y. Effects of Hydrogen Water Treatment on Antioxidant System of Litchi Fruit during the Pericarp Browning. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 127618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, P.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Shao, Y.; Li, W. Ethylene-Induced Postharvest ‘Guifei’ Mango Peel Coloration: Activation of the MiPAL1 Promoter by MiERF5 and the MiERF5-MiMYB7 Complex. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2026, 232, 113999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk Takma, D.; Korel, F. Enhancement of Post-Harvest Quality of Fresh Mandarins with Alginate-Based Edible Coating Containing Natamycin and Vanillin. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 1921–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, Z.S.; Ding, P.; Juju Nakasha, J.; Yusoff, S.F. Combining Chitosan and Vanillin to Retain Postharvest Quality of Tomato Fruit during Ambient Temperature Storage. Coatings 2020, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.U.; Liu, R.; Li, C.; Zhong, S.; Lai, J.; Hasan, M.; Shu, X.; Zeng, L.-Y. Preparation of Vanillin-Taurine Antioxidant Compound, Characterization, and Evaluation for Improving the Post-Harvest Quality of Litchi. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Qin, G.; Li, B. Reactive Oxygen Species Involved in Regulating Fruit Senescence and Fungal Pathogenicity. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013, 82, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Dichio, B.; Xiloyannis, C.; Masia, A. Effects of Different Irradiance Levels on Some Antioxidant Enzymes and on Malondialdehyde Content during Rewatering in Olive Tree. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, C.; Liang, X.; Shu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, M.; He, Y.; Tu, J.; Feng, Y. Bacteriostatic Activity and Resistance Mechanism of Artemisia Annua Extract Against Ralstonia solanacearum in Pepper. Plants 2025, 14, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kou, X.; Zhang, G.; Luo, D.; Cao, S. Exogenous Glycine Betaine Maintains Postharvest Blueberry Quality by Modulating Antioxidant Capacity and Energy Metabolism. LWT 2024, 212, 116976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Tsuda, K. Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid Crosstalk in Plant Immunity. Essays Biochem. 2022, 66, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Kang, L.; Yu, Y. Carbon Monoxide Enhances the Resistance of Jujube Fruit against Postharvest Alternaria Rot. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 168, 111268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kou, X.; Wu, C.; Fan, G.; Li, T. Methyl Jasmonate Induces the Resistance of Postharvest Blueberry to Gray Mold Caused by Botrytis cinerea. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 4272–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gong, D.; Li, M.; Gao, Z.; Sun, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, M. γ-Aminobutyric Acid Enhances Resistance in Postharvest Mango Fruits to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides by Activating Related Defense Mechanisms. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 134, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, C. Expression Patterns of Octoploid Strawberry TGA Genes Reveal a Potential Role in Response to Podosphaera aphanis Infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. Rep. 2020, 14, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, C.; Liu, L.; Huang, D.; Ma, C.; Li, R.; Huang, L. Genome-Wide Identification of the TGA Gene Family in Kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis spp.) and Revealing Its Roles in Response to Pseudomonas syringae Pv. Actinidiae (Psa) Infection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Nonexpressor of Pathogenesis-Related genes 1 (HuNPR1) | GACAGACGAAAGGAGCTTGG | CCACAGCATAGTGGAGAGCA |

| Pathogenesis-Related protein 1 (HuPR1) | GCTCGAGCTTCCCCTAGTTT | GCCCAAAGCTTAACAGCATC |

| Pathogenesis-Related protein 5 (HuPR5) | GCGGATACACTCCACCAAGT | TGCAGGGAAGGGTAAGAGTG |

| TGACG motif-binding factor 1 (HuTGA1) | CTACGAGGACTACTACAGCG | TAGATGAGGTGGAAGATGG |

| Nonexpressor of Pathogenesis-Related genes 5-1 (HuNPR5-1) | TCAAGTCTCCATCGTCCC | TCAGCACCCTCATCACAT |

| Polyphenol Oxidase (HuPPO) | TGTCAGGAGGCCAAAGAAGT | CCTGCATATTCGGCTTTGAT |

| Chitinase (HuCHI) | CAGTCCTGGTCCCAATGCTC | CTTCTGCCATTTGATCGCGG |

| Peroxidase (HuPOD) | CCATCCCAAATCGCACTATA | ATCGGTCCTCAGCATGAAAT |

| Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (HuPAL) | AAGGAACTTCGGCTATCCCG | ACTCCTCCCCAGGAGACTTC |

| Cinnamate 4-Hydroxylase (HuC4H) | AAGTTGAAGCTCCCACCAGG | CTGGCCCATCCTAAGCAACA |

| 4-Coumarate: CoA Ligase (Hu4CL) | TCTTCAAATCACGCCTCCCC | GTTGGAGATGAGACAGGGGC |

| Catalase (HuCAT) | TGCATCCAATACAGGGGAACT | GTTTGGCTTGAATGCGTGGA |

| Superoxide Dismutase (HuSOD) | ACGCTCCGAGAATCTATCCA | CTTTGCACGTACAGTAGGGGA |

| Ascorbate Peroxidase (HuAPX) | AAGGAACGCAACCCTTCCAA | AACCTCTGCCATGGGAAACC |

| Ubiquitin (HuUBQ) | TGAATCATCCGACACCAT | TCCTCTTCTTAGCACCACC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Liu, X.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Aslam, M.M.; Li, R.; Li, W. Vanillin Activates HuTGA1-HuNPR1/5-1 Signaling to Enhance Postharvest Pitaya Resistance to Soft Rot. Foods 2026, 15, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010153

Xu J, Liu X, He Y, Li J, Aslam MM, Li R, Li W. Vanillin Activates HuTGA1-HuNPR1/5-1 Signaling to Enhance Postharvest Pitaya Resistance to Soft Rot. Foods. 2026; 15(1):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010153

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jian, Xinlin Liu, Yilin He, Jinhe Li, Muhammad Muzammal Aslam, Rui Li, and Wen Li. 2026. "Vanillin Activates HuTGA1-HuNPR1/5-1 Signaling to Enhance Postharvest Pitaya Resistance to Soft Rot" Foods 15, no. 1: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010153

APA StyleXu, J., Liu, X., He, Y., Li, J., Aslam, M. M., Li, R., & Li, W. (2026). Vanillin Activates HuTGA1-HuNPR1/5-1 Signaling to Enhance Postharvest Pitaya Resistance to Soft Rot. Foods, 15(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010153