Reviving Forgotten Foods: From Traditional Knowledge to Innovative and Safe Mediterranean Food Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

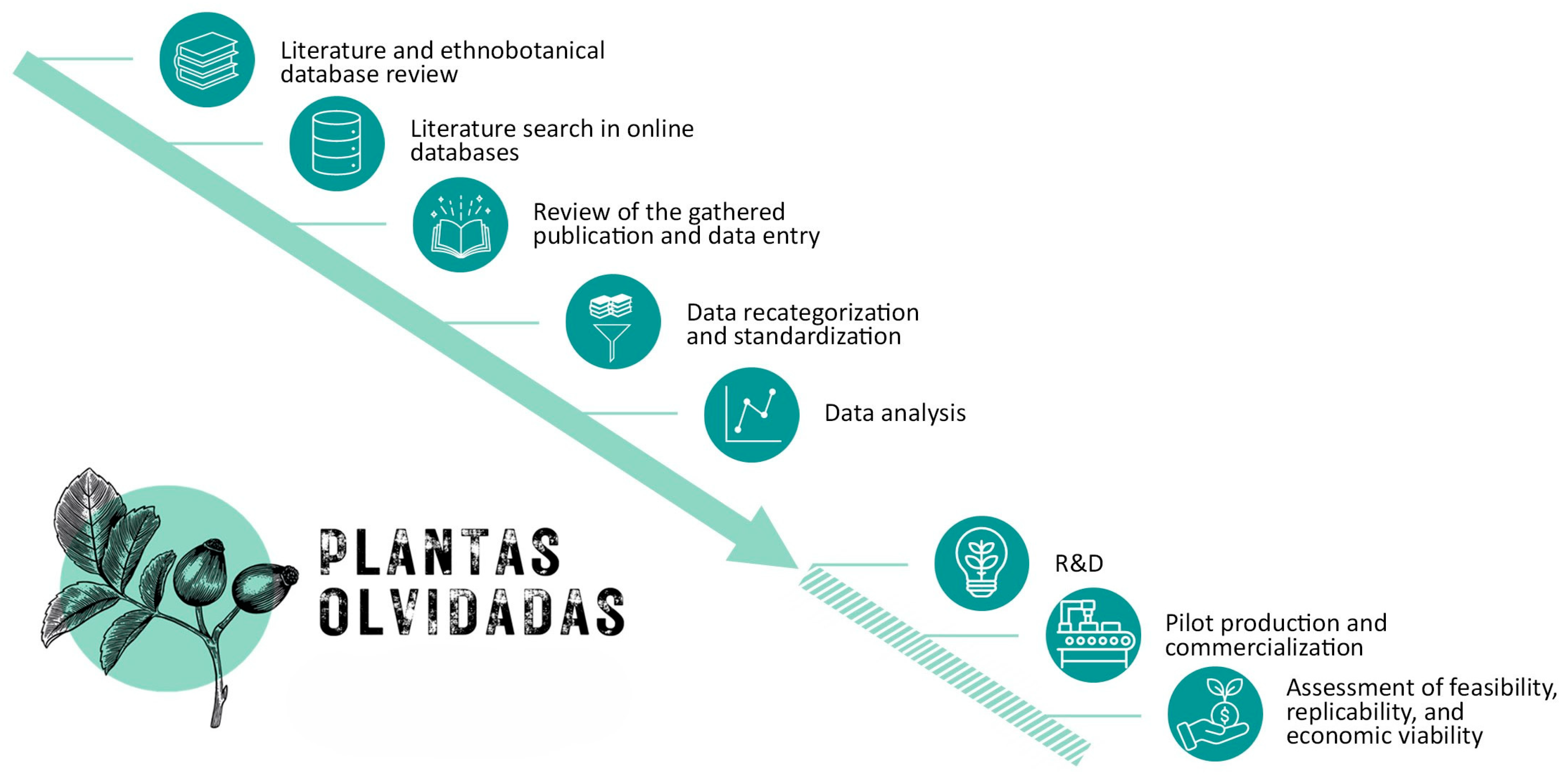

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of Selected Taxa

2.2. Literature Review of Traditional Uses

2.2.1. Search Strategy

2.2.2. Reference Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.2.3. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Analysis of the Gathered Ethnobotanical Data

3. Results and Discussion

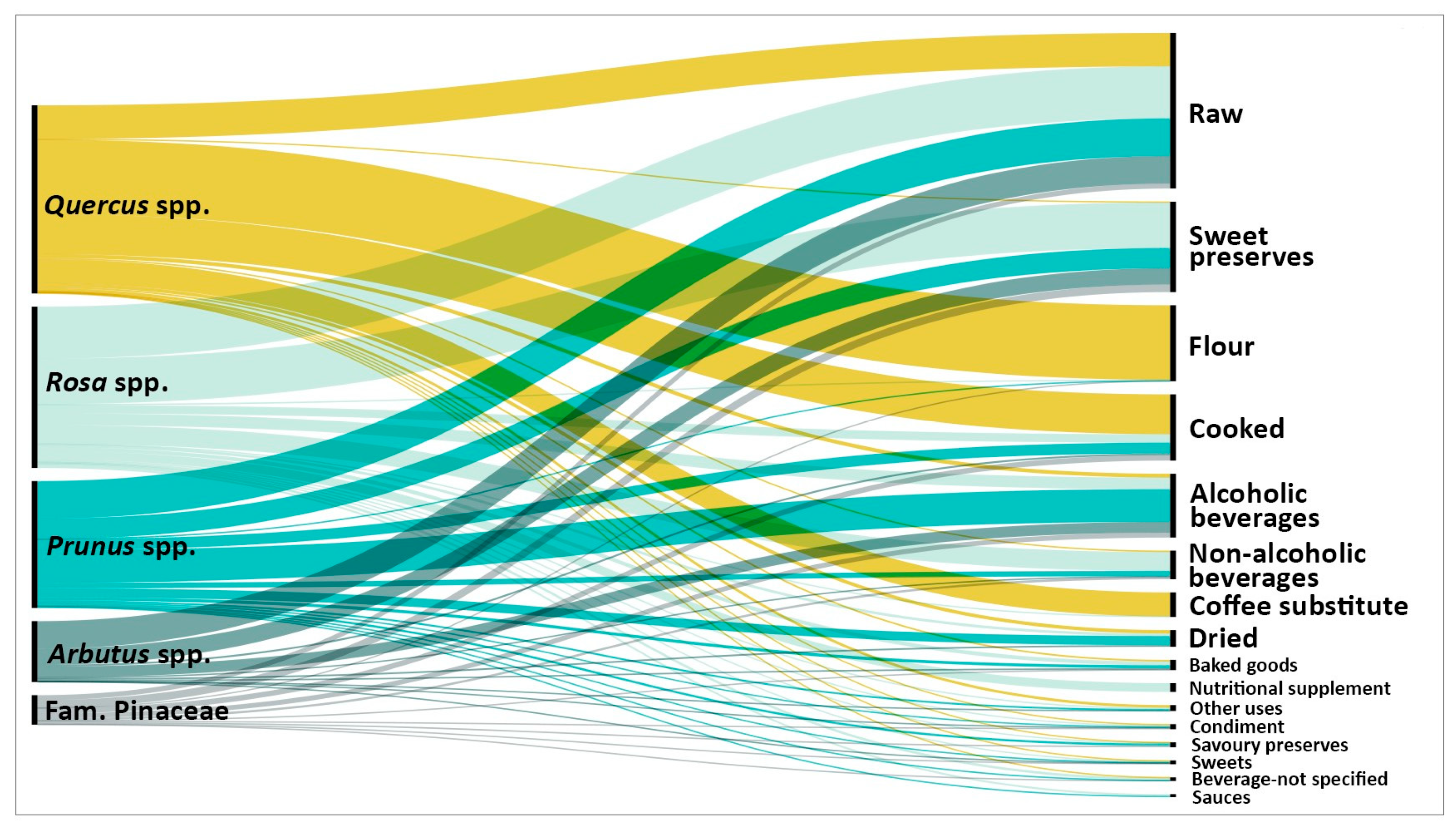

3.1. Traditional Alimentary Uses Through Literature Search

Overview of Traditional Uses by Taxa

- Arbutus spp.

- Prunus spp.

- Quercus spp.

- Pinaceae Family

- Rosa spp.

3.2. Potential Adverse Effects

3.3. From Traditional Knowledge to Innovative Food Products: Opportunities and Limitations

3.4. Legal Considerations for the Utilization of Wild Edible Plants

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinez de Arano, I.M.; Garavaglia, V.; Farcy, C. Forests: Facing the Challenges of Global Change. In MEDITERRA 2016: Zero Waste in the Mediterranean. Natural Resources, Food and Knowledge; International Centre of Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies (CHIEAM) and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); Presses de Sciences Po: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Vayreda, J.; Martinez-Vilalta, J.; Gracia, M.; Canadell, J.G.; Retana, J. Anthropogenic-driven rapid shifts in tree distribution lead to increased dominance of broadleaf species. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 3984–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idescat. Indicadors Bàsics de Catalunya. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=basics&n=10547&tema=terri&t=202300&lang=en (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Idescat. Estadística Del Grau d’urbanització. 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/novetats/?id=5266 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Pinilla, V.; Sáez, L.A. La Despoblación Rural En España: Características, Causas e Implicaciones Para Las Políticas Públicas. In Presupuesto y Gasto Público. 102-(1/2021). Desequilibrios Territoriales y Políticas Públicas; Meño, C.G., Hernández, P., Cos, D., Pérez, J.J., Eds.; Ministerio de Hacienda: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bou Dagher Kharrat, M.; Martinez de Arano, I.; Zeki-Bašken, E.; Feder, S.; Adams, S.; Briers, S.; Fady, B.; Lefèvre, F.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Mauri, E.; et al. Mediterranean Forest Research Agenda 2030; European Forest Institute: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Valls, P.; Jakešová, L.; Vallés, M.; Galiana, F. Sustainability of Mediterranean Spanish forest management through stakeholder views. Eur. Countrys. 2012, 4, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, T.; Pino, J.; Marull, J.; Padró, R.; Tello, E. Understanding the long-term dynamics of forest transition: From deforestation to afforestation in a Mediterranean landscape (Catalonia, 1868–2005). Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Seidl, R.; Delzon, S.; Corona, P.; Kolström, M.; et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Diaz-De-Leon, L.F.; Kangas, P. Evaluation of potential gross income from non-timber products in a model riparian forest for the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Agrofor. Syst. 1998, 44, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, T.; Lv, J.H.; Vu, T.T.H.; Zhang, B. Determinants of non-timber forest product planting, development, and trading: Case study in central Vietnam. Forests 2020, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. Non-Wood Forest Products. Available online: https://www.fao.org/forestry/nwfp/en (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Pereira, A.G.; Fraga-Corral, M.; García-Oliveira, P.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Carpena, M.; Otero, P.; Gullón, P.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Culinary and nutritional value of edible wild plants from northern Spain rich in phenolic compounds with potential health benefits. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 8493–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Villalba, J.; Burló, F.; Hernández, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Valorization of Wild Edible Plants as Food Ingredients and Their Economic Value. Foods 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mata, D.; Morales, R. The Mediterranean Landscape and Wild Edible Plants. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, M.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J. Natural Production and Cultivation of Mediterranean Wild Edibles. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Emery, M.R.; Miina, J.; Kurttila, M.; Corradini, G.; Huber, P.; Vacik, H. Value Creation and Innovation with Non-Wood Forest Products in a Family Forestry Context. In Services in Family Forestry. World Forests; Hujala, T., Toppinen, A.J., Butler, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 24, pp. 185–224. [Google Scholar]

- Knez, M.; Ranić, M.; Gurinović, M. Underutilized plants increase biodiversity, improve food and nutrition security, reduce malnutrition, and enhance human health and well-being. Let’s put them back on the plate! Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heubach, K.; Wittig, R.; Nuppenau, E.A.; Hahn, K. The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: A case study from northern Benin. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Sõukand, R.; Svanberg, I.; Kalle, R. Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe: The disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rius-Agüera, J. Estudio Del Grado de Conocimiento Sobre Nueve Especies Silvestres Comestibles En El Área Metropolitana de Barcelona. Master’s Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.J.; Migliorini, P.; Pieroni, A.; Dreon, A.L.; Sacchetti, L.E.; Paoletti, M.G. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences Edible and Tended Wild Plants, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Agroecology. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 198–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture; Bélanger, J., Pilling, D., Eds.; FAO Commission On Genetic Resources For Food And Agriculture: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Comission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (FAO). Voluntary Guidelines for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Crop Wild Relatives and Wild Food Plants; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2017; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE. Executive Summary of the Report Building Resilient Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Sánchez-Mata, M.d.C., Tardío, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Urugo, M.M.; Tringo, T.T. Naturally Occurring Plant Food Toxicants and the Role of Food Processing Methods in Their Detoxification. Int. J. Food Sci. 2023, 2023, 9947841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Pereira, F.; de Medeiros, F.D.; Araújo, P.L. Natural Toxins in Brazilian Unconventional Food Plants: Uses and Safety. In Local Food Plants of Brazil. Ethnobiology; Jacob, M.C.M., Albuquerque, U.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, A.; Garnatje, T.; Marín, J.; Parada, M.; Sala, E.; Talavera, M.; Vallès, J. The Power of Wild Plants in Feeding Humanity: A Meta-Analytic Ethnobotanical Approach in the Catalan Linguistic Area. Foods 2020, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A. Nutritional Ethnobotany in Europe: From Emergency Foods to Healthy Folk Cuisines and Contemporary Foraging Trends. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Anjos, O.; Canas, S.; Gonçalves, J.C.; Caldeira, I. Development of a spirit drink produced with strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruit and honey. Beverages 2020, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dary Natury. Available online: https://darynatury.pl (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Eesti And. Available online: http://www.eestiand.ee/en (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Eusse-Villa, L.; Franceschinis, C.; Di Cori, V.; Robert, N.; Pettenella, D.; Thiene, M. Societal willingness to pay for wild food conservation in Italy: Exploring spatial dimensions of preferences. People Nat. 2025, 7, 3168–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, G.; Bocanegra-García, V.; Monge, A. Traditional plants as source of functional foods: A review Plantas tradicionales como fuente de alimentos funcionales: Una revisión. CyTA-J. Food 2010, 8, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mata, M.C.; Cabrera Loera, R.D.; Morales, P.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, M.; Díez Marqués, C.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J. Wild vegetables of the Mediterranean area as valuable sources of bioactive compounds. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Cocozza, C.; Gonnella, M.; Abdelrahman, H.; Santamaria, P. Elemental characterization of wild edible plants from countryside and urban areas. Food Chem. 2015, 177, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, A. Indigenous knowledge is key to sustainable food systems. Nature 2023, 613, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cruz, T.E.; Rosado-May, F.J. Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems: Using Traditional Knowledge to Transform Unsustainable Practices 2022. Available online: https://www.rfp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Indigenous-Peoples-Food-Systems-Using-Traditoinal-Knowledge-to-Transform-Unsustainable-Practices.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Plantas Olvidadas: Valorización de Alimentos Forestales Para Una Gestión Sostenible Del Territorio. Available online: https://fundacion-biodiversidad.es/proyecto_prtr/plantas-olvidadas-valorizacion-de-alimentos-forestales-para-una-gestion-sostenible-del-territorio/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Tardío, J.; Sánchez-Mata, M.d.C.; Morales, R.; Molina, M.; García-Herrera, P.; Morales, P.; Díez-Marqués, C.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, M.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; et al. Ethnobotanical and Food Composition Monographs of Selected Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 273–470. [Google Scholar]

- de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Quercus ilex in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2016; p. e014bcd+. [Google Scholar]

- Rouget, M.; Richardson, D.M.; Lavorel, S.; Vayreda, J.; Gracia, C.; Milton, S.J. Determinants of distribution of six Pinus species in Catalonia, Spain. J. Veg. Sci. 2001, 12, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POWO. Rosa L. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30002432-2 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Houston Durrant, T.; De Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Quercus suber in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threaths. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2016; p. e01ff11+. [Google Scholar]

- Enescu, C.M.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G.; Houston Durrant, T. Pinus nigra in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e015138+. [Google Scholar]

- Houston Durrant, T.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Pinus sylvestris in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Treats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e016b94+. [Google Scholar]

- Mauri, A.; Di Leo, M.; De Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Pinus halepensis and Pinus brutia in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e0166b8+. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Aceituno, L.; Molina, M. Inventario Español de Los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a La Biodiversidad; Fase I.; Pardo de Santayana, M., Morales, R., Aceituno, L., Molina, M., Eds.; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2014.

- Batsatsashvili, K.; Mehdiyeva, N.; Fayvush, G.; Kikvidze, Z.; Khutsishvili, M.; Maisaia, I.; Sikharulidze, S.; Tchelidze, D.; Aleksanyan, A.; Alizade, V.; et al. Pinus kochiana Klotzsch Ex K. Koch Pinaceae. In Ethnobotany of the Caucasus, European Ethnobotany; Bussmann, R.W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Batsatsashvili, K.; Mehdiyeva, N.P.; Kikvidze, Z.; Khutsishvili, M.; Maisaia, I.; Sikharulidze, S.; Tchelidze, D.; Alizade, V.M.; Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Bussmann, R.W. Rosa canina L. Rosa iberica Stev. Rosa villosa L. Rosaceae. In Ethnobotany of the Caucasus. European Ethnobotany; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 595–600. [Google Scholar]

- Papp, N.; Purger, D.; Czigle, S.; Czégényi, D.; Stranczinger, S.; Tóth, M.; Dénes, T.; Kocsis, M.; Takácsi-Nagy, A.; Filep, R. The Importance of Pine Species in the Ethnomedicine of Transylvania (Romania). Plants 2022, 11, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papež Kristanc, A.; Kreft, S.; Strgulc Krajšek, S.; Kristanc, L. Traditional Use of Wild Edible Plants in Slovenia: A Field Study and an Ethnobotanical Literature Review. Plants 2024, 13, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikov, A.N.; Tsitsilin, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Makarov, V.G.; Heinrich, M. Traditional and current food use of wild plants listed in the Russian Pharmacopoeia. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolina, K.; Łuczaj, Ł. Wild food plants used on the Dubrovnik coast (South-Eastern Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2014, 83, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidrih, R.; Hribar, J.; Prgomet, Ž.; Ulrih, N.P. The physico-chemical properties of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol 2013, 5, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcão-E-Silva, M.L.C.M.M.; Leitão, A.E.B.; Azinheira, H.G.; Leitão, M.C.A. The Arbutus Berry: Studies on its Color and Chemical Characteristics at Two Mature Stages. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2001, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallauf, K.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; del Castillo, M.D.; Cano, M.P.; de Pascual-Teresa, S. Characterization of the antioxidant composition of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, M.F.; Apahidean, A.I.; Budău, R.; Rosan, C.A.; Popovici, R.; Memete, A.R.; Domocoș, D.; Vicas, S.I. An Overview of the Phytochemical Composition of Different Organs of Prunus spinosa L., Their Health Benefits and Application in Food Industry. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinha, A.F.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Costa, A.S.G.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. A New Age for Quercus spp. Fruits: Review on Nutritional and Phytochemical Composition and Related Biological Activities of Acorns. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 947–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inácio, L.G.; Bernardino, R.; Bernardino, S.; Afonso, C. Acorns: From an Ancient Food to a Modern Sustainable Resource. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, B.; Kozuharova, E.; Stoycheva, C. A Review of Edible Wild Plants Recently Introduced into Cultivation in Spain and Their Health Benefits. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chammam, A.; Fillaudeau, L.; Romdhane, M.; Bouajila, J. Chemical Composition and In Vitro Bioactivities of Extracts from Cones of P. halepensis, P. brutia, and P. pinea: Insights into Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Potential. Plants 2024, 13, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latos-Brozio, M.; Masek, A.; Chrzescijanska, E.; Podsędek, A.; Kajszczak, D. Characteristics of the polyphenolic profile and antioxidant activity of cone extracts from conifers determined using electrochemical and spectrophotometric methods. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchioni, F.; Cioni, P.L.; Flamini, G.; Morelli, I.; Maccioni, S.; Ansaldi, M. Chemical composition of essential oils from needles, branches and cones of Pinus pinea, P. halepensis, P. pinaster and P. nigra from central Italy. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Pacier, C.; Martirosyan, D.M. Rose hip (Rosa canina L): A functional food perspective. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2014, 4, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mata, M.d.C.; Matallana-González, M.C.; Morales, P. The Contribution of Wild Plants to Dietary Intakes of Micronutrients (I): Vitamins. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 111–139. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilj, V.; Brekalo, H.; Petrović, D.; Šaravanja, P.; Batinić, K. Chemical composition and mineral content of fresh and dried fruits of the wild rosehip (Rosa canina L.) population. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2024, 25, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.; Caudullo, G. Prunus spinosa in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e018f4e+. [Google Scholar]

- Backs, J.R.; Ashle, M.V. Quercus conservation genetics and genomics: Past, present, and future. Forests 2021, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A. Geographic variation and phenology of Pinus halepensis, P. brutia and P. eldarica in Israel. For. Ecol. Manag. 1989, 27, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinus halepensis. Available online: https://floracatalana.cat/flora/vasculars/taxons/VTax120 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Horstmann, M.; Buchheit, H.; Speck, T.; Poppinga, S. The cracking of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) cones. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 982756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizoti, P.G.; Kilimis, K.; Gallios, P. Temporal and spatial variation of flowering among Pinus nigra Arn. clones under changing climatic conditions. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinus nigra. Available online: https://floracatalana.cat/flora/vasculars/taxons/VTax125 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Silvestre, S.; Montserrat, P. 13. Rosa L. In Flora Iberica. Volumen VI. LXXXVII. ROSACEAE; Muñoz Garmendia, F., Navarro Aranda, C., Eds.; Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1998; pp. 143–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W.H.; Ertter, B.; Bruneau, A. Rosa Linnaeus. Available online: https://floranorthamerica.org/Rosa (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Exotic fruits as a source of important phytochemicals: Improving the traditional use of Rosa canina fruits in Portugal. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2233–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomljenović, N.; Jemrić, T.; Šimon, S.; Žulj Mihaljević, M.; Gaši, F.; Pejić, I. Genetic variability within and among generative dog rose (Rosa spp.) offsprings. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2019, 20, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plants For A Future (PFAF). Available online: https://pfaf.org/user/Default.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Garnatje, T.; Gras, A.; Parada, M.; Parada, J.; Sobrequés, X.; Vallès, J. Etnobotànica Dels Països Catalans. Versió 1. Available online: https://etnobotanica.iec.cat (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Native American Ethnobotany DB. Available online: http://naeb.brit.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Tardío, J.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Molina, M.; Aceituno, L. (Eds.) Inventario Español de Los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a La Biodiversidad Agrícola; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Volume 1.

- Tardío, J.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Molina, M.; Aceituno, L. (Eds.) Inventario Español de Los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a La Biodiversidad Agrícola; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2022; Volume 2.

- Tardío, J.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Molina, M.; Aceituno, L. (Eds.) Inventario Español de Los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a La Biodiversidad. Fase II. Tomo 1; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- Tardío, J.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Molina, M.; Aceituno, L. (Eds.) Inventario Español de Los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a La Biodiversidad. Fase II. Tomo 2; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- Tardío, J.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Molina, M.; Aceituno, L. (Eds.) Inventario Español de Los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a La Biodiversidad. Fase II. Tomo 3; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- CONECT-e (CONocimiento ECológico Tradicional). Available online: https://www.conecte.es/index.php/es/ (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Corporation for Digital Scholarship. Zotero Version 7.0.27. Available online: https://www.zotero.org/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Mauri, M.; Elli, T.; Caviglia, G.; Uboldi, G.; Azzi, M. RAWGraphs: A Visualisation Platform to Create Open Outputs. In Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI Chapter, Cagliari, Italy, 18–20 September 2017; Volume 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2022. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.J.; Zemla, J. Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. R Package “Corrplot”. Version 0.84 2017. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Kilic, A.; Hafizoglu, H.; Dönmez, I.E.; Tümen, I.; Sivrikaya, H.; Reunanen, M.; Hemming, J. Extractives in the cones of Pinus species. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2011, 69, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.M.; Rotter, M.C.; Ziebarth, E.A.; Carlson, R.E. Volatile Compound Chemistry and Insect Herbivory: Pinus edulis Engelm. (Pinaceae) Seed Cone Resin. Forests 2023, 14, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad Viñas, R.; Caudullo, G.; Oliveira, S.; de Rigo, D. Pinus pinea in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e01b4fc+. [Google Scholar]

- Danna, C.; Poggio, L.; Smeriglio, A.; Mariotti, M.; Cornara, L. Ethnomedicinal and Ethnobotanical Survey in the Aosta Valley Side of the Gran Paradiso National Park (Western Alps, Italy). Plants 2022, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soufleros, E.H.; Mygdalia, S.A.; Natskoulis, P. Production process and characterization of the traditional Greek fruit distillate “Koumaro” by aromatic and mineral composition. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2005, 18, 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça de Carvalho, L. Estudos de Etnobotânica e Botânica Económica No Alentejo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti, L.; Zitti, S.; Taffetani, F. Ethnobotanical uses in the Ancona district (Marche region, Central Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcόn, R.; Pardo-de-santayana, M.; Priestley, C.; Morales, R.; Heinrich, M. Medicinal and local food plants in the south of Alava (Basque Country, Spain). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 176, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piera Alberola, J.H. Plantas Silvestres y Setas Comestibles Del Valle de Ayora Cofrentes; Grupo Acción Local Valle Ayora-Cofrentes: Valencia, Spain, 2006. Available online: https://www.jalance.es/sites/www.jalance.es/files/plantas-silvestres-y-setas-comestibles-del-valle-de-ayora-cofrentes.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Scherrer, A.M.; Motti, R.; Weckerle, C.S. Traditional plant use in the areas of Monte Vesole and Ascea, Cilento National Park (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, R.; Molina, M.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Macía, M.J.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Tardío, J. Arbutus unedo L. In Inventario Español de los Conocimientos Tradicionales relativos a la Biodiversidad. Fase I.; Pardo de Santayana, M., Morales, R., Aceituno, L., Molina, M., Eds.; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Bombons de Modronho, Mestre Cacau. Available online: https://mestrecacau.pt/produto/bombons-de-medronho/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Composta Di Corbezzolo, Sa Mariola. Available online: https://www.samariola.com/composte/composta-di-corbezzolo-selvatico/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Mermelada de Madroño, Palacio Del Dean. Available online: https://www.lasdeliciasdelpalaciodeldean.com/producto/mermelada-de-madrono/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Confiture d’Arbouses Bio Corse, Jean-Paul Vincensini et Fils. Available online: https://corse-bio.fr/fr/confitures-bio-corse/41-confiture-arbouse-bio-corse.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- González, E.A.; Agrasar, A.T.; Castro, L.M.P.; Fernández, I.O.; Guerra, N.P. Solid-state fermentation of red raspberry (Rubus ideaus L.) and arbutus berry (Arbutus unedo, L.) and characterization of their distillates. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, D.E.; Galego, L.; Gonçalves, T.; Quintas, C. Yeast diversity in the Mediterranean strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits’ fermentations. Food Res. Int. 2012, 47, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, S.M.; Gifford, E.W. Karok ethnobotany. Anthropol. Rec. 1952, 13, 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, M.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Aceituno, L.; Morales, R.; Tardío, J. Fruit production of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) in two Spanish forests. Forestry 2011, 84, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulaksız Günaydı, Z.E.; Ayar, A. Phenolic compounds, amino acid profiles, and antibacterial properties of kefir prepared using freeze-dried Arbutus unedo L. and Tamarindus indica L. fruits and sweetened with stevia, monk fruit sweetener, and aspartame. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchikh, Y.; Sahli, S.; Alleg, M.; Mohellebi, N.; Gagaoua, M. Optimised statistical extraction of anthocyanins from Arbutus unedo L. fruits and preliminary supplementation assays in yoghurt. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2021, 74, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, M.; Vallès, J.; Gras, A. Nutritional Properties of Wild Edible Plants with Traditional Use in the Catalan Linguistic Area: A First Step for Their Relevance in Food Security. Foods 2024, 13, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, E.; Bieniek, M.I.; Barbara, B. Composition and antioxidant properties of fresh and frozen stored blackthorn fruits (Prunus spinosa L.). Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2013, 12, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez Cruz, G. Etnobotánica y Etnobiología Del Poniente Granadino. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sõukand, R.; Kalle, R. Changes in the Use of Wild Food Plants in Estonia; SpringerBriefs in Plant Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Tardío, J.; Reyes-García, V. Trends in wild food plants uses in Gorbeialdea (Basque Country). Appetite 2017, 112, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacharán de Las Endrinas. Available online: https://www.bodegaselpilar.com/anisados-y-pacharanes/218-las-endrinas.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Pacharán Ordesano. Available online: https://www.iberowine.es/licores-destilados/pacharan-ordesano (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Musayev, M.; Huseynova, T. Collection, study and use of crop wild relatives of fruit plants in Azerbaijan. Int. J. Minor Fruits Med. Aromat. Plants 2016, 2, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Facciola, S. Cornucopia-A Source Book of Edible Plants; Kampong Publications: Vista, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Aroma de Endrinas. Available online: https://aromasdelsa.es/producto/aroma-de-endrinas/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Endrina Ultracongelada. Available online: https://www.faundez.com/es/productos/detalles/endrina-ultracongelada/105 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Sloe Berry (Blackthorn) Craft Puree®. Available online: https://amoretti.com/products/sloe-berry-blackthorn-craft-puree (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Blackthorn Nectar, Blush & Berry, 500 Ml. Available online: https://www.zoya.bg/en/Blackthorn-nectar.16602 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Blackthorn Pickle. Available online: https://shems.az/en/product/blackthorn-pickle-72 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Extract Prunus spinosa, Gemmo 10+. Available online: https://farmae.eu/es/endrino-100ml-analco-gemmo10-924548201.html?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwwae1BhC_ARIsAK4JfrwDi6LtAbBRO43Y09VdSZj746zOShlt3hk-Qr1R2pO94Oby7VUOQHoaAh_rEALw_wcB (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Torche, Y. Acorn (Quercus spp.) Consumption in Algeria. J. Ethnobiol. 2024, 44, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, S.; Choi, S.; Park, C.-R.; Lee, D.; Gradziel, T. Acorn Production and Utilization in the Republic of Korea; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014.

- Tardío, J.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Molina, M.; Macía, M.J.; Morales, R. Quercus ilex L. In Inventario Español de los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a la Biodiversidad. Fase I.; Pardo, M., Morales, R., Tardío, J., Molina, M., García, I., Eds.; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zocchi, D.M.; Bondioli, C.; Hamzeh Hosseini, S.; Miara, M.D.; Musarella, C.M.; Mohammadi, D.; Khan Manduzai, A.; Dilawer Issa, K.; Sulaiman, N.; Khatib, C.; et al. Food Security beyond Cereals: A Cross-Geographical Comparative Study on Acorn Bread Heritage in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Foods 2022, 11, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, F.Z.; Squeo, G.; Difonzo, G.; Faccia, M.; Pasqualone, A.; Summo, C.; Barkat, M.; Caponio, F. Effects of storage on the oxidative stability of acorn oils extracted from three different Quercus species. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; Li, K.; Bai, J.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, W. The rheological performance and structure of wheat/acorn composite dough and the quality and in vitro digestibility of its noodles. Foods 2021, 10, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, H.; Keramat, J.; Raisee, B. Evaluation of the Cake Quality Made from Acorn-Wheat Flour Blends as a Functional Food. J. Food Biosci. Technol. 2015, 5, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrão Martins, R.; Garzón, R.; Peres, J.A.; Barros, A.I.R.N.A.; Raymundo, A.; Rosell, C.M. Acorn flour and sourdough: An innovative combination to improve gluten free bread characteristics. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendi, A.; Mouselemidou, P.; Papageorgiou, M.; Papastergiadis, E. Effect of acorn meal-water combinations on technological properties and fine structure of gluten-free bread. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korus, J.; Witczak, M.; Ziobro, R.; Juszczak, L. The influence of acorn flour on rheological properties of gluten-free dough and physical characteristics of the bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 240, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Silva, S.; Rodríguez-Alcalá, L.M.; Oliveira, A.; Costa, E.M.; Borges, A.; Martins, C.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Pintado, M.M.E. Quercus based coffee-like beverage: Effect of roasting process and functional characterization. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchelli, S.; Cavuta, T.; Borghi, C.; Cipollaro, M.; Fratini, R.; Bernetti, I. Financial analysis of acorns chain for food production. Forests 2021, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bellota. Available online: https://saboresdebellota.com/producto/harina-de-bellota-en-botella-de-vidrio-450-gramos/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Broa Bolota, Herdade Do Freixo Do Meio. Available online: https://freixoalimento.com/produto/broa-bolota-un-bio-freixo-do-meio (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Colines Artesanos Con Harina de Bellota, Abuela Paula. Available online: https://laabuelapaula.es/varios/colines-artesanos-con-harina-de-bellota-180gr.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Acorn Cookies, Marcie Mayer Maker Lab. Available online: https://www.marciemayer.com/product-page/AcornCookies (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Licor Bellota La Extremeña. Available online: https://www.comprar-bebidas.com/licor-bellota-la-extreme-a?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwrp-3BhDgARIsAEWJ6SzKX3j-Fbsmu8QHM1xv11uPTNZQYtz-slLRmW8nQDMH8lc97qLfqQwaAr_AEALw_wcB (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Organic Cabbage Juice. Available online: https://blog.naver.com/hansan1592/221256051616 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Hamburguer de Bolota Congelado, Herdade Do Freixo Do Meio. Available online: https://freixoalimento.com/produto/hamburguer-de-bolota-congelado-2-unidades-bio (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Acorn Coffee Organic, Dary Natury. Available online: https://darynatury.pl/produkt/kawa-zoledziowka-eko-200-g/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Bussmann, R.W.; Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Sikharulidze, S.; Kikvidze, Z.; Kikodze, D.; Tchelidze, D.; Khutsishvili, M.; Batsatsashvili, K.; Hart, R.E. An ethnobotany of Kakheti and Kvemo Kartli, Sakartvelo (Republic of Georgia), Caucasus. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dénes, A.; Papp, N.; Babai, D.; Czúcz, B.; Molnár, Z. Wild plants used for food by Hungarian ethnic groups living in the Carpathian Basin. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrimus Jarabe de Piña de Abeto, Sudàvel. Available online: https://saudavelherbolario.com/producto/lagrimus-bio-250ml-lagrimus/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Néctum de Piñas de Pino Verde, JoannArteida. Available online: https://www.joannartieda.com/product-page/nectum-de-pino-verde (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Adrià, F.; Soler, J.; Adrià, A. El Bulli 2003–2004; RBA Libros: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rosehip Juice Vitamin C. Polska Róża. Available online: https://polskaroza.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/2024-Polska-Roza-product-catalogue-mail.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Wild Rose Organic Tea, Dary Natury. Available online: https://darynatury.pl/produkt/herbatka-dzika-roza-eko-100-g/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Dei Cas, L.; Pugni, F.; Fico, G. Tradition of use on medicinal species in Valfurva (Sondrio, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 163, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Liu, F.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, M.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, F. Ethnobotanical study of the wild edible and healthy functional plant resources of the Gelao people in northern Guizhou, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaydin, S.; Alibas, I. The influence of short, medium, and long duration common dehydration methods on total protein, nutrients, vitamins, and carotenoids of rosehip fruit (Rosa canina L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 124, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihuan, Z.; Ling, W.; Quanshe, C.; Wusheng, L. Wild fruit resources and exploitation in Xiaoxing’an Mountains. J. For. Res. 1999, 10, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, R.; Valencia, E.; Pedreschi, F.; Diaz, O.; Bastias-Montes, J.; Siche, R.; Muñoz, O. Kinetic deterioration and shelf life in Rose hip pulp during frozen storage. J. Berry Res. 2020, 10, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkova, K.; Polesny, Z. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants used in the Czech Republic. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2015, 88, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andechser Natur Mild Organic Yogurt Rosehip-Cranberry. Available online: https://www.smackway.com/wholesale-products/food/dairy-and-eggs/5082-andechser-natur-mild-organic-yogurt-rosehip-cranberry-3-7-500g (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Grappa Gratacul with Dog Rose, Il Buongustaio. Available online: https://www.ortafood.it/en/prodotto/grappa-gratacul-alla-rosa-canina-75-cl-40-alc/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Rosehip & Cranberries Marmalade Candy, Sweets for Health. Available online: https://www.russiantable.com/products/rosehip-cranberries-marmalade-candy-sugar-free-170g?srsltid=AfmBOooEodsrwhJ0Rq5GNDknBJyco0nHAYUKjAOb4qcKnMG9Jag3LiBd (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Compota de Rose Hip Bio, Probios. Available online: https://www.nutritienda.com/es/probios/compota-de-rose-hip-bio-330g?srsltid=AfmBOooVD62jHJsT6QOiQuSRO06c0fCrUEg7nkc-H3OuZB_Gt6cHVMWX (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Melmelada de Gavarrera Ecològica, Verol. Available online: https://souvenirs.cat/verol/1278-melmelada-de-gavarrera-ecologica-40gr-verol.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Escaramujo BIO En Polvo, FutuNatura. Available online: https://www.futunatura.es/escaramujo-en-polvo (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Zor, M.; Sengul, M. Possibilities of using extracts obtained from Rosa pimpinellifolia L. flesh and seeds in ice cream production. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Bahaa Eldin, A.; Khalifa, I. Valorization and extraction optimization of Prunus seeds for food and functional food applications: A review with further perspectives. Food Chem. 2022, 388, 132955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Acute health risks related to the presence of cyanogenic glycosides in raw apricot kernels and products derived from raw apricot kernels. EFSA J. 2016, 14, e04424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senica, M.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. Fruit Seeds of the Rosaceae Family: A Waste, New Life, or a Danger to Human Health? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10621–10629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, Y.; Cox, P.J.; Jaspars, M.; Nahar, L.; Sarker, S.D. Cyanogenic glycosids from Prunus spinosa (Rosaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2003, 31, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, I.M.; Nikolic, V.D.; Savic-Gajic, I.M.; Nikolic, L.B.; Ibric, S.R.; Gajic, D.G. Optimization of technological procedure for amygdalin isolation from plum seeds (Pruni domesticae semen). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, I.M.; Savic Gajic, I.M. Optimization study on extraction of antioxidants from plum seeds (Prunus domestica L.). Optim. Eng. 2021, 22, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Blázquez, S.; Fernández-Ávila, L.; Gómez-Mejía, E.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E. Development of a green ultrasound-assisted method for the extraction of bioactive oils from sloe seeds: A sustainable alternative to Soxhlet extraction. Microchem. J. 2025, 218, 115364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.C.; Herrero, B. Wild food plants gathered in the upper Pisuerga river Basin, Palencia, Spain. Bot. Lett. 2017, 164, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.T.; Wong, T.Y.; Wei, C.I.; Huang, Y.W.; Lin, Y. Tannins and human health: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 421–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabłowska, E.; Tańska, M. Acorn flour properties depending on the production method and laboratory baking test results: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 980–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dordevic, D.; Zemancova, J.; Dordevic, S.; Kulawik, P.; Kushkevych, I. Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns. Open Agric. 2025, 10, 20250423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Estévez, V.; Garcia Martínez, A.; Mata Moreno, C.; Perea Muñoz, J.M.; Gómez Castro, A.G. Dimensiones y características nutritivas de las bellotas de los Quercus de la dehesa. Arch. Zootec 2008, 57, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Adamczak, A.; Duda, M. Tannin content in acorns (Quercus spp.) from Poland. Dendrobiology 2014, 72, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampidis, V.; Azimonti, G.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Christensen, H.; Fašmon Durjava, M.; Kouba, M.; López-Alonso, M.; López Puente, S.; Marcon, F.; Mayo, B.; et al. Safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of an extract of condensed tannins from Schinopsis balansae Engl. and Schinopsis lorentzii (Griseb.) Engl. (red quebracho extract) for use in all animal species (FEFANA asbl). EFSA J. 2022, 20, 7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisgrana, M.D.R.; Pamies, L.C.G.; Benítez, E.I. Hydrothermal Treatment to Remove Tannins in Wholegrains Sorghum, Milled Grains and Flour. Food Sci. Nutr. Stud. 2019, 3, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center Basque Culinary. Silvestre: La gastronomía de las Plantas; Planeta Gastro: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Amina, M.; Djamel, F.; Djamel, H. Influence of fermentation and germination treatments on physicochemical and functional properties of acorn flour. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 24, 719–726. [Google Scholar]

- Masmoudi, M.; Besbes, S.; Bouaziz, M.A.; Khlifi, M.; Yahyaoui, D.; Attia, H. Optimization of acorn (Quercus suber L.) muffin formulations: Effect of using hydrocolloids by a mixture design approach. Food Chem. 2020, 328, 127082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, M.A. Tannins in Foods: Nutritional Implications and Processing Effects of Hydrothermal Techniques on Underutilized Hard-to-Cook Legume Seeds—A Review. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Escandón, B.E.; Villaviciencio Nieto, M.A.; Ramirez Aguirre, A. Lista de las Plantas Útiles del Estado de Hidalgo; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo: Pachuca, Mexico, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrández, J.V.; Sanz, J.M. Las Plantas en la Medicina Popular de la Comarca de Monzón (Huesca); Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses: Huesca, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Özçelik, H.; Moran, İ. New Methods and New Products in Rosehip Fruit Processing. Bull. Pure Appl. Sci. Bot. 2024, 43, 140–151. [Google Scholar]

- Turkben, C.; Uylaser, V.; Incedayi, B. Influence of traditional processing on some compounds of rose hip (Rosa canina L.) fruits collected from habitat in Bursa, Turkey. Asian J. Chem. 2010, 22, 2309–2318. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Lao, T.; Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Labella-Ortega, M.; Muñoz Triviño, M.; Pedrosa, M.; Rey, M.D.; Jorrín-Novo, J.V.; Castillejo-Sánchez, M.Á. Proteomic identification of allergenic proteins in holm oak (Quercus ilex) seeds. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; Domínguez, C.; Cosmes, P.; Martínez, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Martínez, J.; Palacios, R. Anaphylactic reaction to ingestion of Quercus ilex acorn nut. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1998, 28, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapatero, L.; Baeza, M.L.; Sierra, Z.; Molero, M.I.M. Anaphylaxis by fruits of the Fagaceae family: Acorn and chesnut. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005, 60, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando-Ibernón, G.; Schneller-Pavelescu, L.; Silvestre-Salvador, J.F. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by “Rosa mosqueta” oil. Contact Dermatitis 2018, 79, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Compendium of botanicals reported to contain naturally occuring substances of possible concern for human health when used in food and food supplements. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster-Boluda, I.; Vidal-Capilla, I. Consumer attitudes in the election of functional foods. Spanish J. Mark.-ESIC 2017, 21, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Benyei, P.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Gras, A.; Molina, M.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Documenting and protecting traditional knowledge in the era of open science: Insights from two Spanish initiatives. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyu, C.G.; Bereka, T.Y. Review on contribution of indigenous food preparation and preservation techniques to attainment of food security in Ethiopian. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Choi, Y.; Sang, H.; Junsoo, J. Effect of different cooking methods on the content of vitamins and true retention in selected vegetables. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, O.V.; Milea, Ș.A.; Păcularu-Burada, B.; Andronoiu, D.G.; Râpeanu, G.; Stănciuc, N. Technologically Driven Approaches for the Integrative Use of Wild Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) Fruits in Foods and Nutraceuticals. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenturk, S.; Gulaboglu, M.S.; Gultekin, S. The effects of cutting and drying medium on the vitamin C content of rosehip during drying. J. Food Eng. 2005, 68, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalec, K.; Wąsik, R.; Gach, M.B. The content of vitamin C in dog rose fruit Rosa canina L. depending on the method and duration of storage. Sylwan 2023, 67, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orak, H.H.; Aktas, T.; Yagar, H.; Isbilir, S.S.; Ekinci, N.; Sahin, F.H. Antioxidant activity, some nutritional and colour properties of vacuum dried strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruit. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2011, 10, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Orak, H.H.; Aktas, T.; Yagar, H.; Isbilir, S.S.; Ekinci, N.; Sahin, F.H. Effects of hot air and freeze drying methods on antioxidant activity, colour and some nutritional characteristics of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruit. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2012, 18, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B.; Wang, B. Effects of infrared freeze drying on volatile profile, FTIR molecular structure profile and nutritional properties of edible rose flower (Rosa rugosa flower). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 4791–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallustio, V.; Marto, J.; Gonçalves, L.M.; Mandrone, M.; Chiocchio, I.; Protti, M.; Mercolini, L.; Luppi, B.; Bigucci, F.; Abruzzo, A.; et al. Influence of Various Fruit Preservation Methods on the Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Prunus spinosa L. Fruit Extract. Plants 2025, 14, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallawi, T. Arbutus unedo L. and OcimumbBasilicum L. as Sources of Natural Ingredients for Bread Functionalization. Master’s Thesis, Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, Bragança, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaz Yuksel, A. The Effects of Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) Addition on Certain Quality Characteristics of Ice Cream. J. Food Qual. 2015, 38, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, A.; Tamer, C.E. Determination of suitability of black carrot (Daucus carota L. spp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) juice concentrate, cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus), blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) and red raspberry (Rubus ideaus). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1524–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Makhlouf, F.Z.; Barkat, M.; Difonzo, G.; Summo, C.; Squeo, G.; Caponio, F. Effect of acorn flour on the physico-chemical and sensory properties of biscuits. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, A.; Ahari, H.; Asadi, G.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A. Enhancement of the quality and preservation of frozen burgers by active coating containing Rosa canina L. extract nanoemulsions. Food Chem. X 2024, X23, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, M.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, M.; Gui, M.; Luo, J.; Bao, A.; Qin, W.; Gao, X. Dynamic Flavor Changes of Rosa roxburghii Juice during Frozen Storage. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2024, 45, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Hodak, A.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Marić, M.; Juračak, J. Traditional Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the Central Lika Region (Continental Croatia)—First Record of Edible Use of Fungus Taphrina pruni. Plants 2022, 11, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djerrad, Z.; Kadik, L.; Djouahri, A. Chemical variability and antioxidant activities among Pinus halepensis Mill. essential oils provenances, depending on geographic variation and environmental conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 74, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calama Sainz, R.; Tome, M.; Sánchez-González, M.; Miina, J.; Spanos, K.; Palahi, M. Modelling Non-Wood Forest Products in Europe: A review. For. Syst. 2010, 19, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaschuk, N.; Gauthier, J.; Bullock, R. Developing community-based criteria for sustaining non-timber forest products: A case study with the Missanabie Cree First Nation. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 158, 103104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission EU Novel Food Status Catalogue. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/food-feed-portal/screen/novel-food-catalogue/search (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on Novel Foods, Amending Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1852/2001; Official Journal of the European Union: 2015. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015R2283 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2998 on Food Additives. 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32008R1333 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers, Amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004; Official Journal of the European Union, 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:304:0018:0063:en:PDF (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ley 43/2003, de 21 de Noviembre, de Montes. Spain. 2003. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2003/BOE-A-2003-21339-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ley 6/1988, de 13 de Marzo, Forestal de Cataluña. 1988. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es-ct/l/1988/03/30/6/dof/spa/pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ley 7/1999, de 30 de Julio, Del Centro de La Propiedad Forestal. 1999. Available online: https://portaldogc.gencat.cat/utilsEADOP/PDF/2948/1421794.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Fundación FairWild. 2011. Estándar FairWild: Versión 2.0.; Traducida de la Versión Original: FairWild Foundation; FairWild Standard: Version 2.0.; FairWild Foundation: Weinfelden, Switzerland, 2010.

- Consello Regulador da Agricultura Ecolóxica de Galicia. Normas Técnicas de La Producción Agraria Ecológica Para La Recolección de Productos Silvestres. NT-03, 4th ed.; 2018; Available online: https://www.craega.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2019-04-25-NT-03-Ed5-Recolecci%C3%B3n-es.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Els Corremarges SCCL. Recol·lectar i Conservar. Guia de Bones Pràctiques per a La Recol·lecció Sostenible En El Mosaic Agroforestal; Paisatges Cooperatius: Catalonia, Spain, 2022.

| Arbutus spp. | Fam. Pinaceae | Prunus spp. | Quercus spp. | Rosa spp. | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | 137 | 25 | 188 | 167 | 260 | 777 |

| Sweet preserves | 81 | 38 | 101 | 4 | 227 | 451 |

| Flour | 0 | 1 | 2 | 372 | 4 | 379 |

| Cooked | 9 | 27 | 54 | 199 | 42 | 331 |

| Coffee substitute | 0 | 0 | 0 | 119 | 3 | 122 |

| Dried | 8 | 0 | 45 | 17 | 13 | 83 |

| Baked goods | 7 | 2 | 15 | 8 | 19 | 51 |

| Nutritional supplement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 43 |

| Condiment | 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 25 |

| Savory preserves | 0 | 7 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 24 |

| Sweets | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 19 |

| Sauces | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 15 |

| Other uses | 1 | 0 | 9 | 13 | 7 | 30 |

| Alcoholic beverage | 54 | 24 | 163 | 19 | 58 | 318 |

| Non-alcoholic beverage | 4 | 11 | 27 | 7 | 94 | 143 |

| Beverage—not specified | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 18 |

| TOTAL | 304 | 147 | 634 | 939 | 805 |

| Use Reports | Number of Alimentary Uses [Out of 54] | Number of Categories [Out of 16] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbutus spp. | 304 | 21 | 10 |

| Fam. Pinaceae | 147 | 19 | 11 |

| Prunus spp. | 634 | 34 | 14 |

| Quercus spp. | 939 | 35 | 14 |

| Rosa spp. | 805 | 36 | 16 |

| Plant Part | Arbutus spp. | Fam. Pinaceae | Prunus spp. | Quercus spp. | Rosa spp. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects | ||||||

| Overconsumption may cause headaches | F | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | |||

| Possible alcohol content—risk of intoxication | F | 6 (2%) | ||||

| Avoid seed consumption—toxic compounds | Se | 88 (14%) | ||||

| Presence of tannins | F | 194 (21%) | ||||

| Presence of irritant hairs | F/Se | 138 (17%) | ||||

| Consume in moderation—it causes constipation | F | 6 (1%) | ||||

| TOTAL | 7 (2%) | NA | 88 (14%) | 195 (21%) | 144 (18%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Balant, M.; Català-Altés, J.; Garnatje, T.; Cáceres, F.; Blasco-Moreno, C.; Fernández-Arévalo, A.; Knudsen, C.; De Luca, V.; Peters, J.; Sanz-Benito, I.; et al. Reviving Forgotten Foods: From Traditional Knowledge to Innovative and Safe Mediterranean Food Design. Foods 2026, 15, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010150

Balant M, Català-Altés J, Garnatje T, Cáceres F, Blasco-Moreno C, Fernández-Arévalo A, Knudsen C, De Luca V, Peters J, Sanz-Benito I, et al. Reviving Forgotten Foods: From Traditional Knowledge to Innovative and Safe Mediterranean Food Design. Foods. 2026; 15(1):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010150

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalant, Manica, Judit Català-Altés, Teresa Garnatje, Fuencisla Cáceres, Clara Blasco-Moreno, Anna Fernández-Arévalo, Clàudia Knudsen, Valeria De Luca, Jana Peters, Ignacio Sanz-Benito, and et al. 2026. "Reviving Forgotten Foods: From Traditional Knowledge to Innovative and Safe Mediterranean Food Design" Foods 15, no. 1: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010150

APA StyleBalant, M., Català-Altés, J., Garnatje, T., Cáceres, F., Blasco-Moreno, C., Fernández-Arévalo, A., Knudsen, C., De Luca, V., Peters, J., Sanz-Benito, I., Casabosch, M., Talavera, M., López-Viñallonga, E., Cárdenas Samsó, C., Cuberos-Sánchez, N., Cepas-Gil, A., Vallès, J., & Gras, A. (2026). Reviving Forgotten Foods: From Traditional Knowledge to Innovative and Safe Mediterranean Food Design. Foods, 15(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010150