From Information to Satisfaction: Unravelling the Impact of Sustainability Label on Fish Liking Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Consumer Sample

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Consumer Evaluation

- Session I

- Session II

2.4. Statistical Analysis

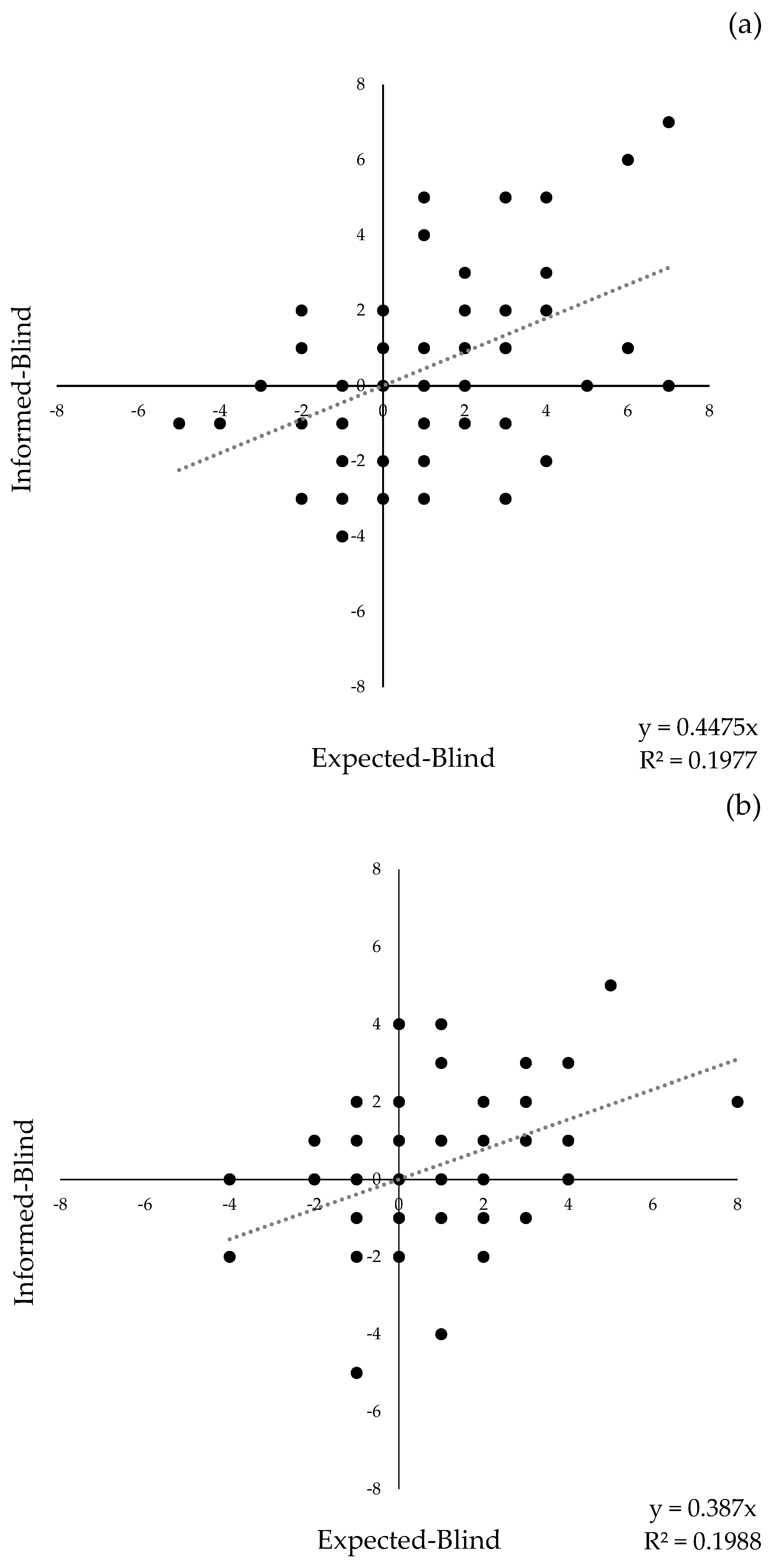

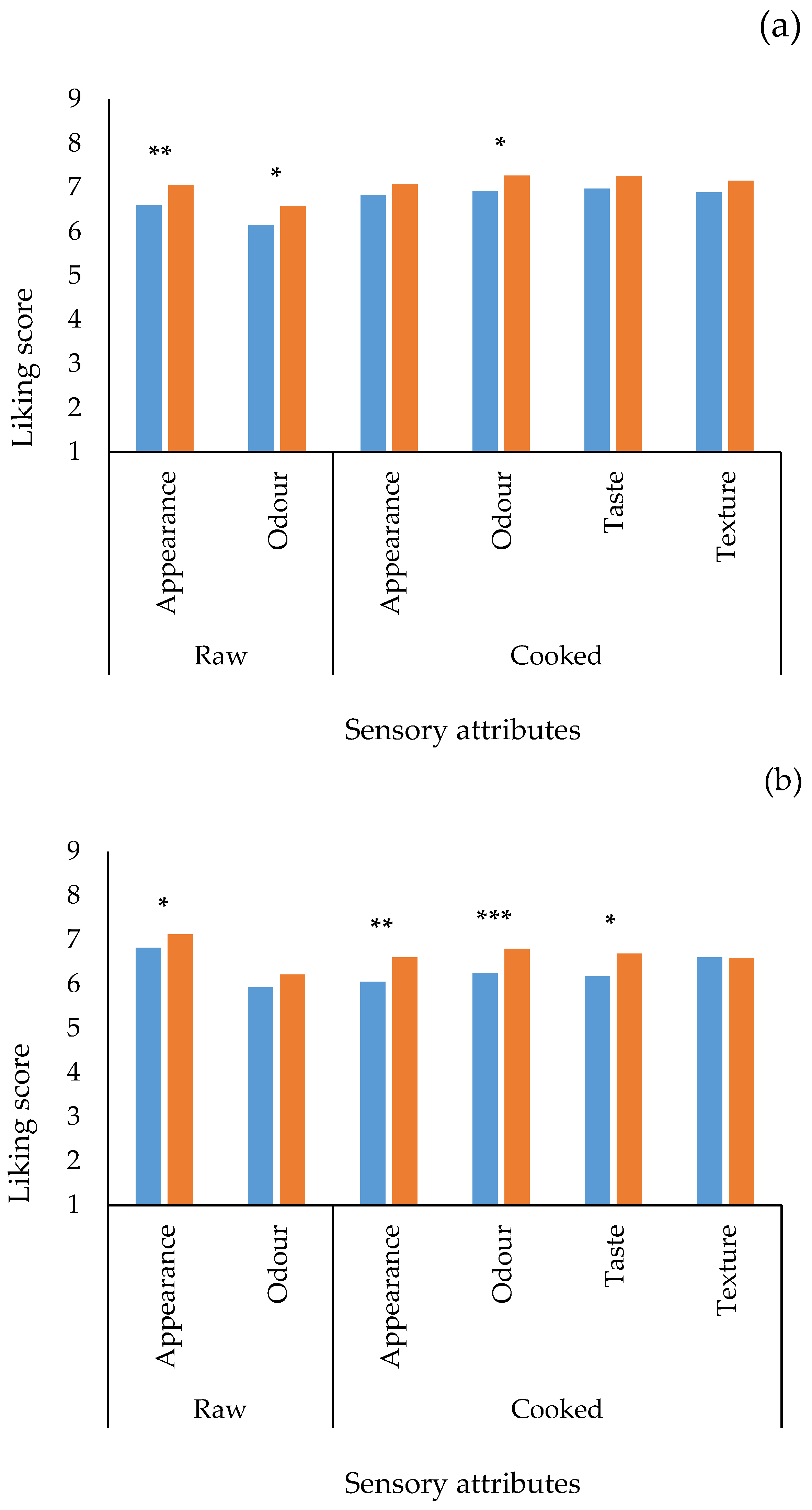

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Consumers’ Characteristics

3.2. Consumer Test

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, N.; Turchini, G.M. The evolution of the blue-green revolution of rice-fish cultivation for sustainable food production. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1375–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Herrero, L.; De Menna, F.; Vittuari, M. Sustainability concerns and practices in the chocolate life cycle: Integrating consumers’ perceptions and experts’ knowledge. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorile, G.; Puleo, S.; Colonna, F.; Mincione, S.; Masi, P.; Solana, N.H. Consumers’ Awareness of Fish Traceability and Sustainability: An Exploratory Study in Italy and Spain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bussel, L.M.; Kuijsten, A.; Mars, M.; van’t Veer, P. Consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, J.; Bailey, M. Perceptions of aquaculture ecolabels: A multi-stakeholder approach in Nova Scotia, Canada. Mar. Policy 2018, 87, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolzenbach, S.; Bredie, W.L.P.; Christensen, R.H.B.; Byrne, D.V. Impact of product information and repeated exposure on consumer liking, sensory perception and concept associations of local apple juice. Food Res. Int. 2013, 52, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaishi, T.; Chapman, A. Eco-labels as a communication and policy tool: A comprehensive review of academic literature and global label initiatives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boopendranath, M.R. Seafood Ecolabelling. Fish. Technol. 2013, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Maesano, G.; Di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; Pappalardo, G.; D’amico, M. The role of credence attributes in consumer choices of sustainable fish products: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, D.; Nocella, G.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Bimbo, F.; Nardone, G. Consumer purchasing behaviour towards fish and seafood products. Patterns and insights from a sample of international studies. Appetite 2015, 84, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomarra, M.; Crescimanno, M.; Vrontis, D.; Miret Pastor, L.; Galati, A. The ability of fish ecolabels to promote a change in the sustainability awareness. Mar. Policy 2021, 123, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.M.M.; Bush, S.R. Authority without credibility? Competition and conflict between ecolabels in tuna fisheries. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, J.; Bartolino, V.; Waldo, S. Price Premiums for Providing Eco-labelled Seafood: Evidence from MSC-certified Cod in Sweden. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 66, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Hoffmann, J. Consumer preferences for farmed and ecolabeled turbot: A North German perspective. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2018, 22, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, H.; Onozaka, Y.; Morita, T.; Managi, S. Demand for ecolabeled seafood in the Japanese market: A conjoint analysis of the impact of information and interaction with other labels. Food Policy 2014, 44, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, C.; D’Aniello, A. Tell me more and make me feel proud: The role of eco-labels and informational cues on consumers’ food perceptions. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1365–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauracher, C.; Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato, D. Consumer preferences regarding the introduction of new organic products. The case of the Mediterranean sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in Italy. Appetite 2013, 63, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salladarré, F.; Brécard, D.; Lucas, S.; Ollivier, P. Are French consumers ready to pay a premium for eco-labeled seafood products? A contingent valuation estimation with heterogeneous anchoring. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roheim, C.A.; Asche, F.; Santos, J.I. The elusive price premium for ecolabelled products: Evidence from seafood in the UK market. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 62, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Mariani, A.; Vecchio, R. Effectiveness of sustainability labels in guiding food choices: Analysis of visibility and understanding among young adults. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, M.C.; Punzo, G. How environmental sustainability labels affect food choices: Assessing consumer preferences in southern Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 130046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Miret-Pastor, L.; Siggia, D.; Crescimanno, M.; Fiore, M. Determinants affecting consumers’ attention to fish eco-labels in purchase decisions: A cross-country study. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2993–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, J.S.; Mársico, E.T.; da Cruz, A.G.; de Freitas, M.Q.; Doro, L.H.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Effect of sustainability information on consumers’ liking of freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 3160–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, J.C.; de Aguiar Sobral, L.; Ares, G.; Deliza, R. Understanding consumers’ perception of lamb meat using free word association. Meat Sci. 2016, 117, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandstra, E.H.; Lion, R. In-home testing. Context Eff. Environ. Prod. Des. Eval. 2019, 4, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, K.A.; Hamid, N.; Jaeger, S.R.; Delahunty, C.M. Effects of evoked consumption contexts on hedonic ratings: A case study with two fruit beverages. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 26, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, J.C.; Nalério, E.S.; Giongo, C.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Ares, G.; Deliza, R. Consumer sensory and hedonic perception of sheep meat coppa under blind and informed conditions. Meat Sci. 2018, 137, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliza, R. External Cues and Its Effect on Sensory Perception and Hedonic Ratings: A Review. J. Sens. Stud. 1995, 11, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.M.; Delahunty, C.M. Mapping consumer preference for the sensory and packaging attributes of Cheddar cheese. Food Qual Prefer. 2000, 11, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Monaco, R.; Cavella, S.; Di Marzo, S.; Masi, P. The effect of expectations generated by brand name on the acceptability of dried semolina pasta. Food Qual Prefer. 2004, 15, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, G.; Monteleone, E. Effect of expectations induced by information on origin and its guarantee on the acceptability of a traditional food: Olive oil. Sci. Aliment. 2001, 21, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.; Pennino, M.G.; Albo-Puigserver, M.; Steenbeek, J.; Bellido, J.M.; Coll, M. SOS small pelagics: A safe operating space for small pelagic fish in the western Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 756, 144002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelić Mrčelić, G.; Nerlović, V.; Slišković, M.; Zubak Čižmek, I. An Overview of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Farming Sustainability in the Mediterranean with Special Regards to the Republic of Croatia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, A.; Sacchi, G.; Cavallo, C.; Cicia, G.; Di Monaco, R.; Puleo, S.; Del Giudice, T. Drivers of fish choice: An exploratory analysis in Mediterranean countries. Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuorila, H.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Pohjalainen, L.; Lotti, L. Food neophobia among the Finns and related responses to familiar and unfamiliar foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2001, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predieri, S.; Sinesio, F.; Monteleone, E.; Spinelli, S.; Cianciabella, M.; Daniele, G.M.; Dinnella, C.; Gasperi, F.; Endrizzi, I.; Torri, L.; et al. Gender, age, geographical area, food neophobia and their relationships with the adherence to the mediterranean diet: New insights from a large population cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, S.; Prescott, J.; Pierguidi, L.; Dinnella, C.; Arena, E.; Braghieri, A.; Di Monaco, R.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Endrizzi, I.; Proserpio, C.; et al. Phenol-rich food acceptability: The influence of variations in sweetness optima and sensory-liking patterns. Nutrients 2021, 13, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schouteten, J.J.; De Steur, H.; De Pelsmaeker, S.; Lagast, S.; Juvinal, J.G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verbeke, W.; Gellynck, X. Emotional and sensory profiling of insect-, plant- and meat-based burgers under blind, expected and informed conditions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouteten, J.J.; De Steur, H.; Sas, B.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Gellynck, X. The effect of the research setting on the emotional and sensory profiling under blind, expected, and informed conditions: A study on premium and private label yogurt products. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Rondoni, A.; Bari, R.; Smith, R.; Mansilla, N. Effect of information on consumers’ sensory evaluation of beef, plant-based and hybrid beef burgers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Sources of positive and negative emotions in food experience. Appetite 2008, 50, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paakki, M.; Kantola, M.; Junkkari, T.; Arjanne, L.; Luomala, H.; Hopia, A. “Unhealthy = Tasty”: How Does It Affect Consumers’ (Un)Healthy Food Expectations? Foods 2022, 11, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, S.; Masi, C.; Dinnella, C.; Zoboli, G.P.; Monteleone, E. How does it make you feel? A new approach to measuring emotions in food product experience. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 37, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.M.H.; Crocker, C.; Marketo, C.G. Linking sensory characteristics to emotions: An example using dark chocolate. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B.; Spence, C. Sensory expectations based on product-extrinsic food cues: An interdisciplinary review of the empirical evidence and theoretical accounts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUMOFA. The EU Fish Market 2020; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2020; 170p. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, A.; Lund, E.; Amiano, P.; Dorronsoro, M.; Brustad, M.; Kumle, M.; Rodriguez, M.; Lasheras, C.; Janzon, L.; Jansson, J.; et al. Variability of fish consumption within the 10 European countries participating in the European Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronnmann, J.; Asche, F. Sustainable Seafood From Aquaculture and Wild Fisheries: Insights From a Discrete Choice Experiment in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. Green marketing consumer-level theory review: A compendium of applied theories and further research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1848–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviglio, A.; Demartini, E.; Mauracher, C.; Pirani, A. Consumer perception of different species and presentation forms of fish: An empirical analysis in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 36, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Consumers (n) | Male (n) | Female (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 49 | 14 | 35 |

| 30–44 | 30 | 8 | 22 |

| >45 | 26 | 14 | 12 |

| Provenance | |||

| Seaside | 65 | 22 | 43 |

| Internal | 40 | 14 | 26 |

| Education | |||

| Middle school diploma | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| High school diploma | 30 | 15 | 15 |

| Bachelor’s | 52 | 13 | 39 |

| Master’s/Ph.D. | 17 | 5 | 12 |

| Sample | E | B | I | E-B | I-B | I-E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchovy | 7.3 ± 1.5 c | 6.3 ± 1.9 a | 6.8 ± 1.7 b | 0.98 *** | 0.50 ** | −0.5 * |

| Tuna | 7.5 ± 1.5 b | 6.6 ± 1.5 a | 7.0 ± 1.4 a | 0.84 *** | 0.36 * | −0.5 ** |

| Gender | Age | Provenance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Liking | M | F | p-Value | 18–29 | 30–44 | >45 | p-Value | Seaside | Internal | p-Value |

| Anchovy | E | 7.3 | 7.3 | 0.883 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 0.52 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 0.448 |

| B | 6.2 | 6.4 | 0.689 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 0.200 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 0.462 | |

| I | 6.6 | 6.9 | 0.327 | 6.3 a | 7.4 b | 7.1 ab | 0.010 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 0.680 | |

| Tuna | E | 7.5 | 7.5 | 0.948 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 0.111 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 0.423 |

| B | 6.3 | 6.8 | 0.176 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 0.177 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 0.726 | |

| I | 6.9 | 7.0 | 0.722 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 0.319 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 0.596 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiorile, G.; Puleo, S.; Colonna, F.; Del Giudice, T.; Di Monaco, R. From Information to Satisfaction: Unravelling the Impact of Sustainability Label on Fish Liking Experiences. Foods 2025, 14, 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050890

Fiorile G, Puleo S, Colonna F, Del Giudice T, Di Monaco R. From Information to Satisfaction: Unravelling the Impact of Sustainability Label on Fish Liking Experiences. Foods. 2025; 14(5):890. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050890

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiorile, Giovanni, Sharon Puleo, Francesca Colonna, Teresa Del Giudice, and Rossella Di Monaco. 2025. "From Information to Satisfaction: Unravelling the Impact of Sustainability Label on Fish Liking Experiences" Foods 14, no. 5: 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050890

APA StyleFiorile, G., Puleo, S., Colonna, F., Del Giudice, T., & Di Monaco, R. (2025). From Information to Satisfaction: Unravelling the Impact of Sustainability Label on Fish Liking Experiences. Foods, 14(5), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050890