Analysis of the Quality of Selected Vegetarian Products Available on the Polish Market Compared to Their Homemade Equivalents

Abstract

1. Introduction

General Characteristics of Selected Vegetarian Products Considering Their Nutritional Value

2. Materials and Methods

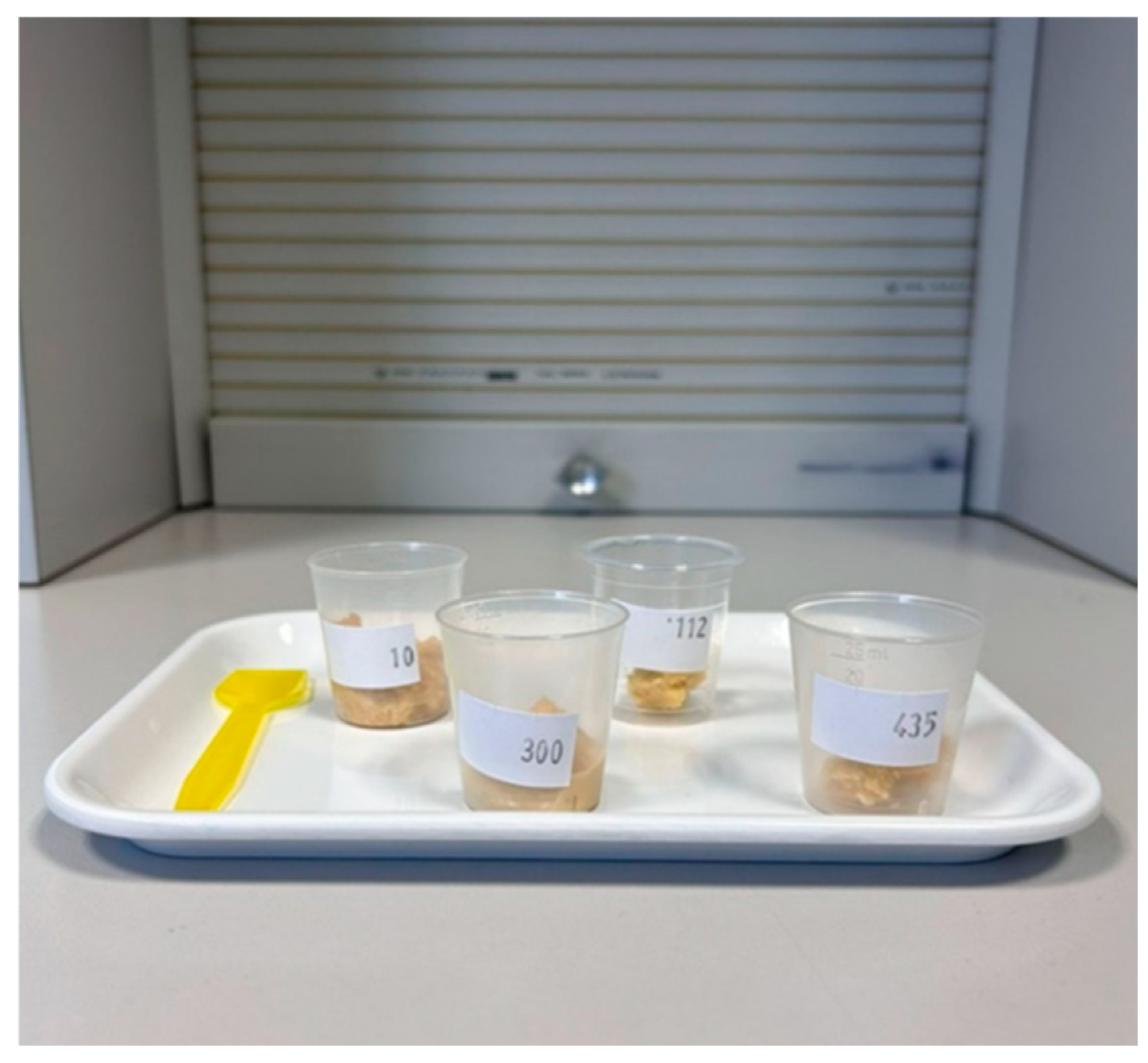

2.1. Sensory Experiment Design

2.2. Evaluation of Vegetarian Products Using the Five-Point Method

2.3. Evaluation of Vegetarian Products Using the Ranking Method

2.4. Assessment of Consumer Preferences and Eating Behaviour

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nutritional Value of Selected Hummus Pastes

3.2. Nutritional Value of Selected Falafels

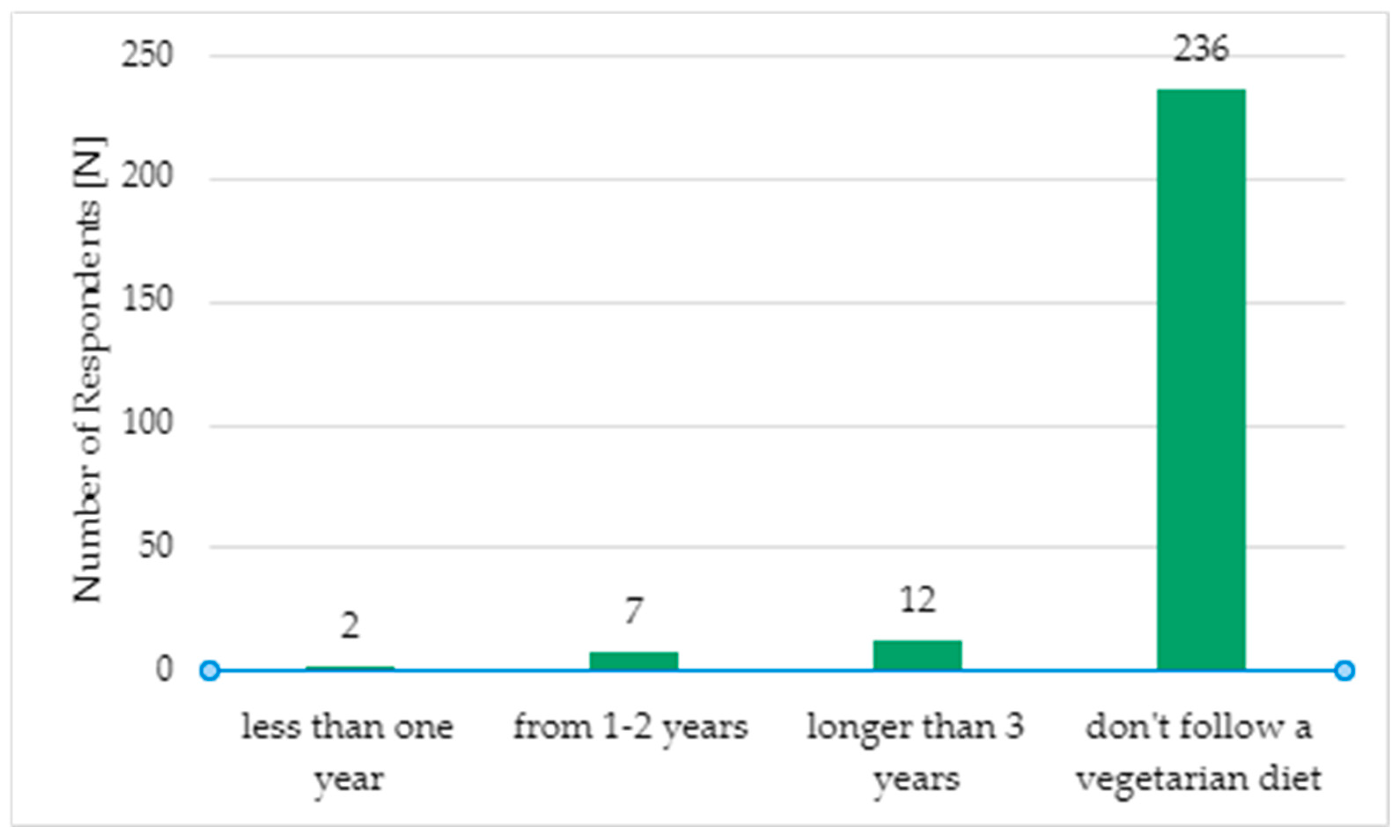

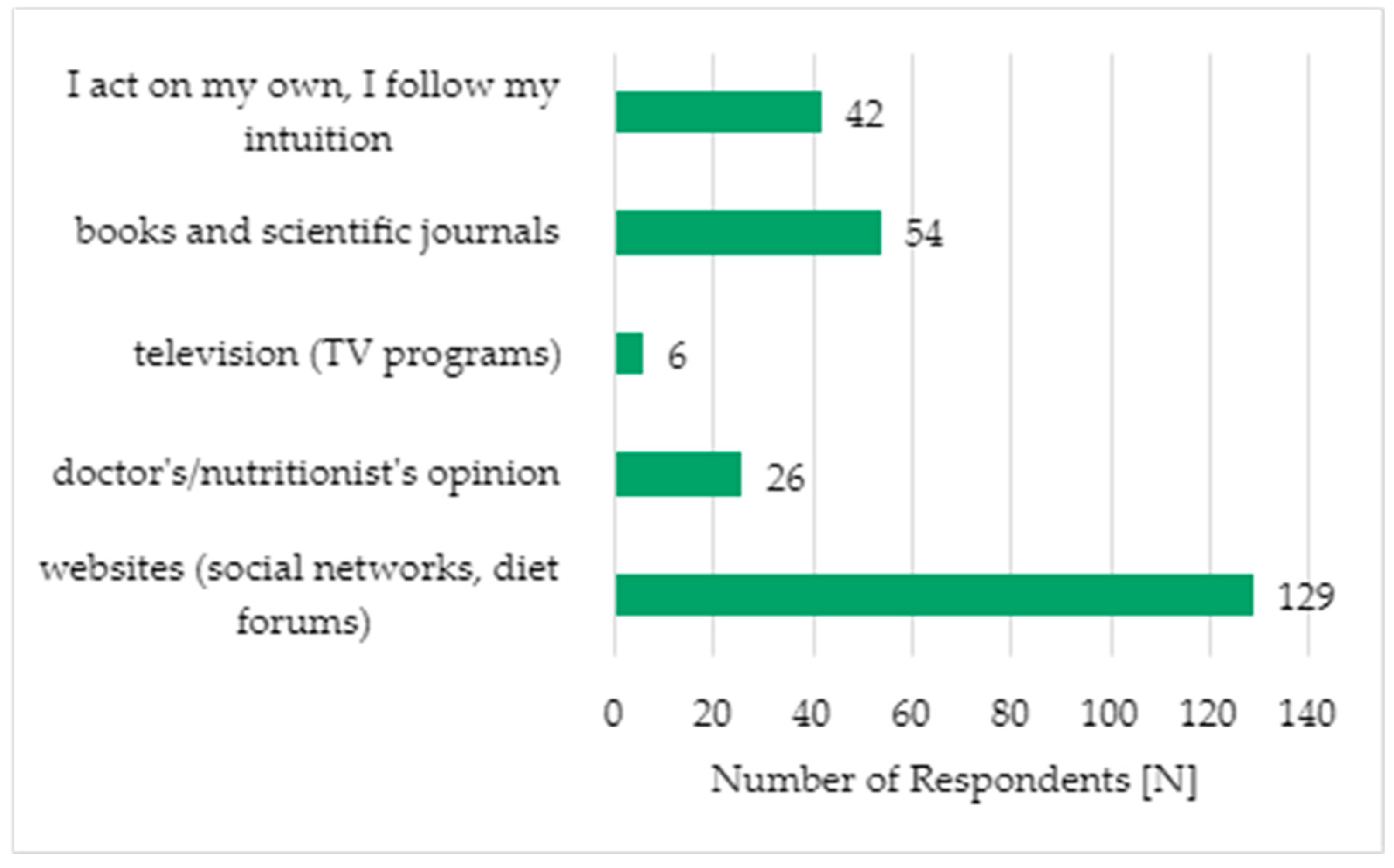

3.3. Preferences and Dietary Behavior Concerning the Consumption of Vegetarian Products Available on the Polish Market

3.4. Results of the Sensory Evaluation of Vegetarian Products Using the Five-Point Scale Method

3.5. Results of the Sensory Evaluation of Vegetarian Products Using the Ranking Method

4. Discussion

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Preparation Method for Hummus Paste “Hummus with Homemade Tahini”

- Weigh and place sesame seeds into a bowl.

- Toast the sesame seeds in a dry, preheated pan until they turn golden brown.

- Grind the toasted sesame seeds, add olive oil, and blend thoroughly to form a smooth tahini paste.

- In a separate container, combine chickpeas, canned liquid (aquafaba), garlic, salt, cumin, and lemon juice.

- Blend all ingredients until a smooth and creamy consistency is achieved.

- Transfer the prepared hummus paste to another container for serving or storage.

Appendix A.2. Preparation Method for “Herb Falafels”

- Finely chop the prepared onion, garlic, and parsley.

- Add canned chickpeas, cumin, chili, and salt to the chopped ingredients.

- Blend all the ingredients using a blender until a smooth mixture is formed.

- Incorporate flour and baking powder into the mixture.

- Refrigerate the mixture for approximately 1 h to allow it to firm up.

- Shape small patties from the chilled mixture, about 2 cm thick.

- Heat oil in a non-stick pan.

- Fry the falafels over a medium heat for 3–4 min on each side, until they turn golden brown.

- Drain any excess oil from the fried falafels using a paper towel.

| Product | Preparation of the Product for Testing | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Pasta hummus | Storage of products in the refrigerator until serving. | Separation of samples weighing approximately 15 g. |

| Proprietary falafel | Frying the product for 5 min on each side in a small amount of oil. Cutting the products into small pieces (squares). | Separation of samples weighing approximately 30 g. |

| Falafel | The other falafels did not require any special preparation prior to administration for the study. | Separation of samples weighing approximately 30 g. |

Appendix B

References

- Mehta, V. Vegetarian diet: A boon or bane for health? J. Med. Res. Innov. 2018, 2, e000084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Halloran, A.; Rippin, H.L.; Oikonomidou, A.C.; Dardavesis, T.I.; Williams, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Chourdakis, M. Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet. A systematic review of the evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3503–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocarska, A. Postrzeganie wegańskiej oferty rynkowej przez konsumentów w Polsce w świetle badań ankietowych. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 21, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, A.U.; Herstatt, C.; Tiwari, R.; Dedehayir, O.; Mäkinen, J.S. The vegan trend and the microfundations of institutional change: A commentatory on food producers’ sustainable innovation journeys in Europe. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, V.; Ladwig, B. Ethical Consumerism: Veganism. WIREs Clim. Change 2020, 12, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, I.; Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C.M. Modelling attitude towards consumption of vegan products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.M.; Rosenfeld, D.L.; Moreira, A.V.B.; Zandonadi, R.P. Plant-based and vegetarian diets: An overview and definition of these dietary patterns. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.M.; Raposo, A.; Saraiva, A.; Zandonadi, R.P. Vegetarian diet: An overview through the perspective of quality of life domains. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cader, P.; Lesiów, T. Weganizm i wegetarianizm jako diety we współczesnym społeczeństwie konsumpcyjnym. Nauk. Inżynierskie Technol. 2021, 37, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Vegetarian Union (IVU). Definitions. 2013. Available online: https://ivu.org/definitions.html (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A.; WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibil, I. Wege Dieta Roślinna w Praktyce; Gajewska, D., Ed.; PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowska, S.K. Porównanie cen i składów wybranych hummusów dostępnych na rynku. In Koła Naukowe—Szkołą Twórczego Działania, Tom 4; Nauki Rolnicze i Weterynaryjne, Cz. 1.; Tańska, M., Sosna, P., Eds.; ABADA: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenfeld, C.L.; Wallance, T.C. Dietary patterns and nutritional status in relation to consumption of chickpeas and hummus in the U.S. population. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondyra-Wiśniewska, B.; Kaczorek, M.; Pacyna, S.; Wedziuk, A.; Nagel, P.; Pawluk, I. Legumes Are Healthy! A Practical Nutritional Guide on Reducing Meat Consumption in Favor of Plant-Based Products; National Institute of Public Health—National Research Institute (PZH–NIPH): Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/E-book-Straczkowe-sa-zdrowe.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Reister, E.J.; Belote, L.N.; Leidy, H.J. The benefits of including hummus and hummus ingredients into the American diet to promote diet quality and health: A comprehensive review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutepova, I.; Rehm, C.D.; Friend, S.J. UK Chickpea Consumption Doubled from 2008/09-2018/19. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrojewicz, Z.; Majewski, J.; Pająk, J.; Majewski, M. Hummus—trochę egzotyki na talerzu. Med. Rodzinna 2017, 20, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falafel “K-Take It Veggie” Label; Kaufland: Neckarsulm, Germany, 2024.

- Falafel with Chickpeas and Spelt Label; Soligrano: Dobroń, Poland, 2024.

- PN-EN ISO 8589:2010; Sensory Analysis–General Guidelines for the Design of Sensory Analysis Laboratories. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Baryłko-Piekielna, N.; Matuszewska, I. Sensory Analysis of Food. Fundamentals, Methods, Applications; Polish Society of Food Technologists (PTTŻ): Kraków, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, V. Nutritional and health benefits of dried beans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 1, 437S–442S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanat-Kańtoch, G.; Białek-Dratwa, A. Alternative Diets in Nutritional Counseling. In Alternative Nutrition Guide; Białek-822 Dratwa, A., Grajek, M., Eds.; Medical University of Silesia: Katowice, Poland, 2022; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, B.; dos Santos, P.A. Protein recommendations for vegetarians and vegans. Health Soc. 2024, 4, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Masedunskas, A.; Willett, W.C.; Fontana, L. Vegetarian and vegan diets: Benefits and drawbacks. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3423–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. Revealed: Countries with the Most Vegetarians in the World. 2024. Available online: https://ceoworld.biz/2024/01/21/revealed-countries-with-the-most-vegetarians-in-the-world-2024/ (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Goluch, Z.; Izydorczyk, M.; Tomaszewska, M. Frequency and Preferences for Consumption of Fortified Products by Women Following a Vegetarian Diet. In Medicine and Health in the Modern World; ArchaeGraph: Łódź, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwińska, A.; Olszówka, M.; Pieszko, M. Knowledge Assessment on Vegetarian Diets among the Tri-City Population. Sci. J. Gdynia Marit. Univ. 2014, 86, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bettinelli, M.E.; Bezze, E.; Morasca, L.; Plevani, L.; Sorrentino, G.; Morniroli, D.; Giannì, M.L.; Mosca, F. Knowledge of Health Professionals Regarding Vegetarian Diets from Pregnancy to Adolescence: An Observational Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian Diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankojć, A.; Lesiów, T.; Biazik, E. Quorn™ Meat Substitutes on the Polish Market. Part 2. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2016, 4, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Janowicz, M.; Ciurzyńska, A.; Zielińska, M.; Lenart, A. “Convenient” Vegetable Ready Meals in Consumer Evaluation. Food Process. Technol. Adv. 2018, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, T.C.; Murray, R.; Zelman, K.M. The nutritional value and health benefits of chickpeas and hummus. Nutrients 2016, 780, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, L.; Yamani, M.I. A Study of Physical, Chemical, and Sensory Characteristics of Novel Legume Dips. Int. J. Food Sci. 2024, 2024, 2875348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Plant Product | Qualitative Composition |

|---|---|

| Pasta Hummus | |

| Natural hummus | cooked chickpeas bio (61%), water, sunflower oil bio, tahini bio (sesame paste bio), sea salt, apple cider vinegar bio, dried garlic bio |

| Hummus natural, organic, gluten-free, bio | soaked chickpeas (56%), water, sunflower oil, sesame paste (16%), sea salt, garlic, cumin, acidity regulator: lactic acid |

| Traditional hummus | chickpeas (57%), rapeseed oil, water, tahini sesame paste, lemon juice concentrate, salt, dried garlic, romaine cumin |

| Proprietary hummus 1 | sesame seeds, olive oil, white chickpeas in brine, lemon juice, garlic, salt, roma cumin |

| Falafel | |

| Falafel traditional, bio | chickpeas (48%), onion, chickpea flour, courgette, mint (2%), corn grits, sea salt, sesame seeds (1%), parsley, lemon juice (1%), spices, sunflower oil |

| Vegan falafel | soaked chickpeas (50%), courgette, onion, breadcrumbs (wheat flour, yeast, salt), sunflower oil, parsley, cumin, salt, acidity regulator (potassium acetate, citric acid), coriander, garlic powder, black pepper |

| Falafel with chickpeas and spelt | chickpea flour (41%), heat-prepared spelt flour (39%), dried onion, dried parsley, spices (salt, garlic, chili, ginger, coriander, cinnamon, romaine cumin) |

| Proprietary falafel 1 | white onion, garlic, parsley leaves, chickpeas in brine, romaine, salt, chili, spelt flour, baking powder |

| Names of Selected Hummus Pastes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Value per 100 g of Product | Natural Hummus | Hummus Natural. Organic. Gluten-Free. Bio | Traditional Hummus | Proprietary Hummus 1 |

| Energy value [kJ/kcal] | 1060/256 | 1210/289 | 782/189 | 1269/303.5 |

| Fat [g]/ saturated fatty acids [g] | 18.7/2.2 | 24.9/3.3 | 13.8/1.1 | 27.4/2.33 |

| Carbohydrates [g]/ sugars [g] | 10.0/1.7 | 5.9/1.2 | 7.5/0.6 | 11.6/2.1 |

| Dietary fiber [g] | 6.7 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 4.2 |

| Protein [g] | 8.5 | 7.5 | 4.7 | 5.2 |

| Salt [g] | 1.05 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| Names of Selected Falafel Types | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Value per 100 g of Product | Falafel Traditional. Bio | Vegan Falafel | Falafel with Chickpeas and Spelt | Proprietary Falafel 1 |

| Energy value [kJ/kcal] | 1052.0/252.0 | 845.0/203.0 | 1455.0/345.0 | 1755.8/419.4 |

| Fat [g]/ saturated fatty acids [g] | 11.0/1.3 | 11.2/1.3 | 3.9/0.7 | 19.7/1.9 |

| Carbohydrates [g]/ sugars [g] | 22.0/3.4 | 14.0/1.7 | 54.0/7.8 | 50.7/1.2 |

| Dietary fiber [g] | 12.0 | 10.1 | 13.0 | 7.6 |

| Protein [g] | 11.0 | 6.5 | 17.0 | 17.0 |

| Salt [g] | 1.9 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 0.5 |

| Sources of Knowledge | Age Groups | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13–18 Years Old | 18–24 Years Old | 24–40 Years Old | ||

| Websites (social networks, diet forums) | 72 (55.4%) | 49 (49.5%) | 8 (32.0%) | p < 0.0001 * |

| Doctor’s/nutritionist’s opinion | 12 (9.2%) | 10 (10.1%) | 4 (16.0%) | |

| Television (TV programs) | 6 (4.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Books and scientific journals | 10 (7.7%) | 29 (29.3%) | 15 (53.6%) | |

| I act on my own. I follow my intuition | 30 (23.1%) | 11 (11.1%) | 1 (4.0%) | |

| Total [N] | 130 | 99 | 28 | |

| Use of a Vegetarian Diet | Level of Education | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (N = 131) | Secondary (N = 72) | Higher (N = 54) | ||

| Yes | 13 (9.9%) | 14 (19.4%) | 23 (42.6%) | p = 0.001 * |

| No | 63 (48.1%) | 39 (54.2%) | 22 (40.7%) | |

| Do not know | 55 (42.0%) | 19 (26.4%) | 9 (16.7%) | |

| Product Quality Features | Validity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Large | Large | Average | Small | |||||

| [N] | [%] | [N] | [%] | [N] | [%] | [N] | [%] | |

| Price | 40 | 15.6 | 122 | 47.5 | 82 | 31.9 | 13 | 5.1 |

| Product brand | 10 | 3.9 | 70 | 27.2 | 111 | 43.2 | 66 | 25.7 |

| Pack size | 18 | 7.0 | 97 | 37.7 | 106 | 41.3 | 36 | 14.0 |

| Product composition | 109 | 42.4 | 91 | 35.4 | 44 | 17.1 | 13 | 5.1 |

| Taste | 186 | 72.4 | 65 | 25.3 | 6 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Best before date | 95 | 36.96 | 98 | 38.1 | 53 | 20.6 | 11 | 4.3 |

| Product Quality Features | [N] | Me | K0.25 | K0.75 | Xmin/Xmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | 257 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0/4.0 |

| Product brand | 257 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0/4.0 |

| Pack size | 257 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0/4.0 |

| Product composition | 257 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 1.0/4.0 |

| Taste | 257 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0/4.0 |

| Best before date | 257 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 1.0/4.0 |

| Product | Test Code | Quality Indicator | IC | [N] | SD | Me | Xmin/Xmax | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural hummus | 435 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 1.2/5.2 | ||

| Hummus natural, organic, gluten-free, bio | 300 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 1.2/5.2 | ||

| Traditional hummus | 112 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 1.2/5.2 | ||

| Proprietary hummus 1 | 10 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 1.2/5.2 | ||

| p-value ε2 | Appearance | 0.017 * 0.03 | ||||||

| Color | <0.001 * 0.07 | |||||||

| Aroma | <0.001 * 0.19 | |||||||

| Texture | <0.001 * 0.12 | |||||||

| Taste | 0.153 0.02 | |||||||

| Product | Test Code | Quality Indicator | IC | [N] | SD | Me | Xmin/Xmax | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falafel traditional, bio | 455 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 1.3/5.2 | ||

| Vegan falafel | 222 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.2/5.2 | ||

| Falafel with chickpeas and spelt | 60 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.2/5.2 | ||

| Proprietary falafel 1 | 100 | Appearance | 0.15 | 126 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2/0.8 |

| Color | 0.10 | 126 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1/0.5 | ||

| Aroma | 0.25 | 126 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3/1.3 | ||

| Texture | 0.15 | 126 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.2/0.8 | ||

| Taste | 0.35 | 126 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.4/1.8 | ||

| Total Points | 1 | 126 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 4.2 | 1.2/5.2 | ||

| p-value ε2 | Appearance | <0.001 * 0.23 | ||||||

| Color | <0.001 * 0.06 | |||||||

| Aroma | <0.001 * 0.20 | |||||||

| Texture | <0.001 * 0.05 | |||||||

| Taste | <0.001 * 0.05 | |||||||

| Product | Test Code | Quality Indicator | [N] | SD | Me | Xmin/Xmax | p-Value ε2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural hummus | 435 | Appearance | 131 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 1.0/4.0 | <0.001 * 0.10 |

| Hummus natural, organic, gluten-free, bio | 300 | Appearance | 131 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0/4.0 | |

| Traditional hummus | 112 | Appearance | 131 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0/4.0 | |

| Proprietary hummus 1 | 10 | Appearance | 131 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0/4.0 | |

| Falafel traditional, bio | 455 | Appearance | 131 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0/4.0 | <0.001 * 0.15 |

| Vegan falafel | 222 | Appearance | 131 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0/4.0 | |

| Falafel with chickpeas and spelt | 60 | Appearance | 131 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0/4.0 | |

| Proprietary falafel 1 | 100 | Appearance | 131 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0/4.0 |

| Product | Test Code | Quality Indicator | [N] | SD | Me | Xmin ÷ Xmax | p-Value ε2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural hummus | 435 | Taste | 131 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 | <0.001 * 0.04 |

| Hummus natural, organic, gluten-free, bio | 300 | Taste | 131 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 | |

| Traditional hummus | 112 | Taste | 131 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 | |

| Proprietary hummus 1 | 10 | Taste | 131 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 | |

| Falafel traditional, bio | 455 | Taste | 131 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 | <0.001 * 0.20 |

| Vegan falafel | 222 | Taste | 131 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 | |

| Falafel with chickpeas and spelt | 60 | Taste | 131 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 | |

| Proprietary falafel 1 | 100 | Taste | 131 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 ÷ 4.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiciak, A.; Kuczka, N.; Barczyńska, R.; Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W.; Białek-Dratwa, A.; Sapała, A.-M.; Kowalski, O.; Kardas, M. Analysis of the Quality of Selected Vegetarian Products Available on the Polish Market Compared to Their Homemade Equivalents. Foods 2025, 14, 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050891

Kiciak A, Kuczka N, Barczyńska R, Staśkiewicz-Bartecka W, Białek-Dratwa A, Sapała A-M, Kowalski O, Kardas M. Analysis of the Quality of Selected Vegetarian Products Available on the Polish Market Compared to Their Homemade Equivalents. Foods. 2025; 14(5):891. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050891

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiciak, Agata, Natalia Kuczka, Renata Barczyńska, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, Agnieszka Białek-Dratwa, Anna-Maria Sapała, Oskar Kowalski, and Marek Kardas. 2025. "Analysis of the Quality of Selected Vegetarian Products Available on the Polish Market Compared to Their Homemade Equivalents" Foods 14, no. 5: 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050891

APA StyleKiciak, A., Kuczka, N., Barczyńska, R., Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W., Białek-Dratwa, A., Sapała, A.-M., Kowalski, O., & Kardas, M. (2025). Analysis of the Quality of Selected Vegetarian Products Available on the Polish Market Compared to Their Homemade Equivalents. Foods, 14(5), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050891