Fractionation and Chemical Characterization of Cell-Bound Biosurfactants Produced by a Novel Limosilactobacillus fermentum Strain via Cheese Whey Valorization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Culture Conditions

2.2. Cheese Whey Utilization for Biosurfactant Production

2.3. Biosurfactant Production Using CW

2.4. Extraction of Biosurfactants

2.5. Fractionation of Biosurfactants with Column Chromatography

2.6. Surface Tension Measurements

2.7. Stability Tests

2.8. Analytical Methods

2.8.1. Lactose, Lactic Acid, and Monosaccharides Determination

2.8.2. Analysis of Total Dry Weight (TDW)

2.8.3. Spectrophotometric Methods

2.8.4. Total Lipid Content Determination

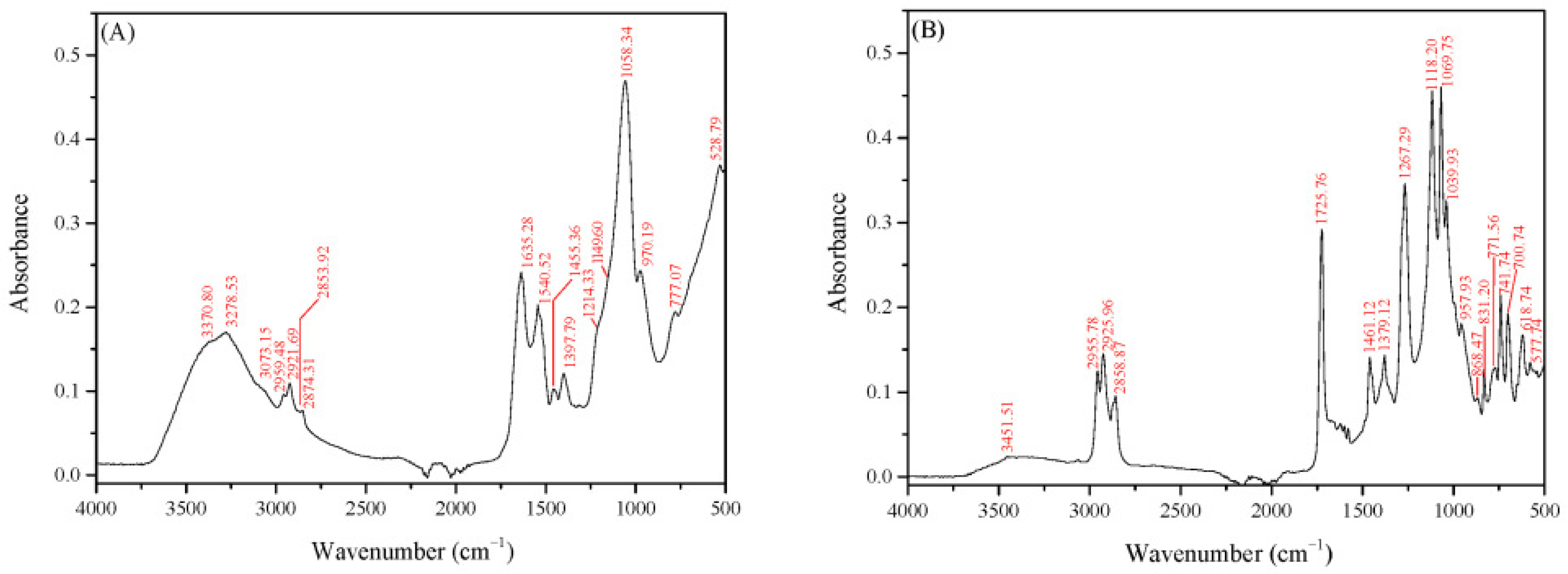

2.8.5. Structural Analysis of BS Using FTIR

2.8.6. Carbohydrate Analysis of Biosurfactants

2.8.7. Amino Acid Analysis of Biosurfactants

Extraction of Free Amino Acids

Hydrolysis of the Peptide Fraction of BS

RP-HPLC Analysis of Amino Acids

2.8.8. Determination of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters with Gas Chromatography (GC)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

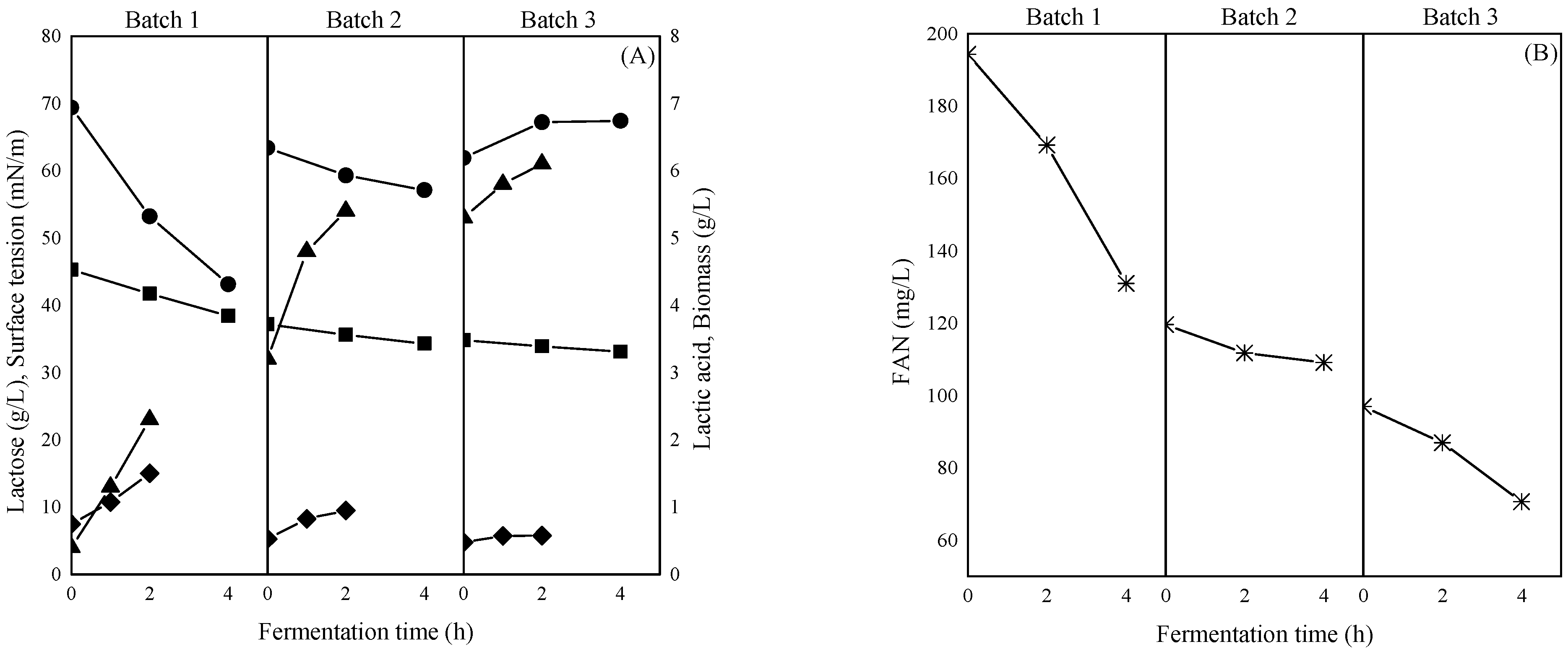

3.1. Biosurfactants Production in Repeated Batch Fermentation with Substrate “Recycling”

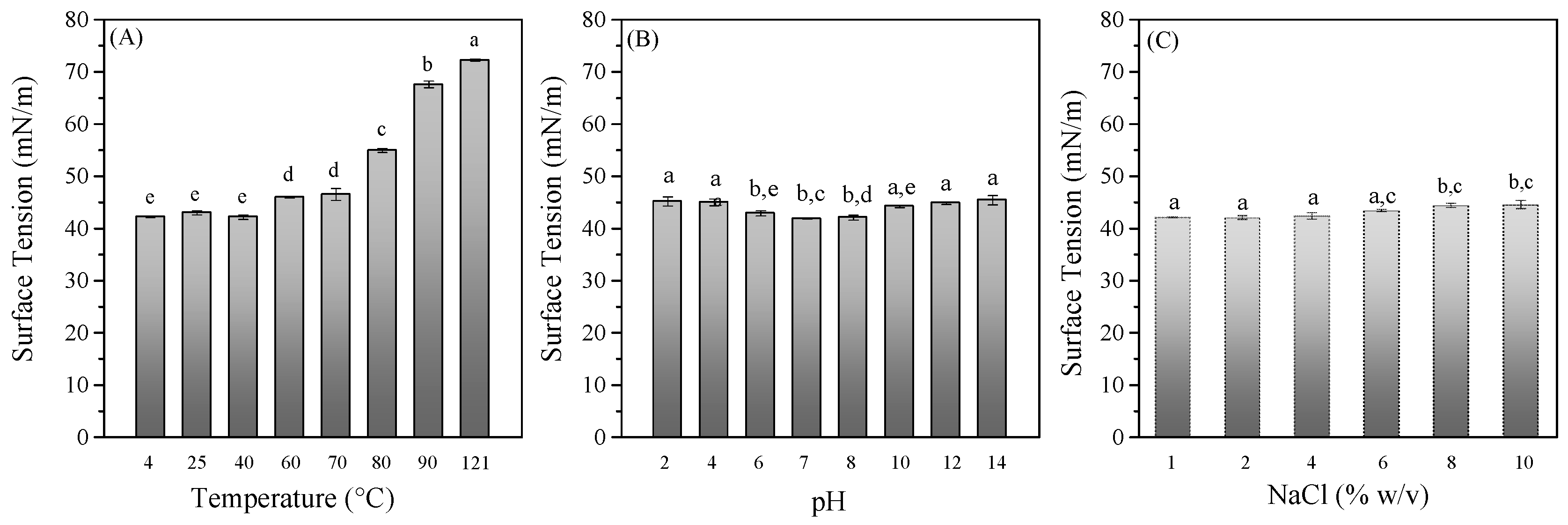

3.2. Evaluation of BS Stability

3.3. Structural Characterization of the Crude Biosurfactants

3.3.1. Fatty Acid Analysis

3.3.2. Amino Acid Analysis

3.3.3. Analysis of the Carbohydrate Moiety

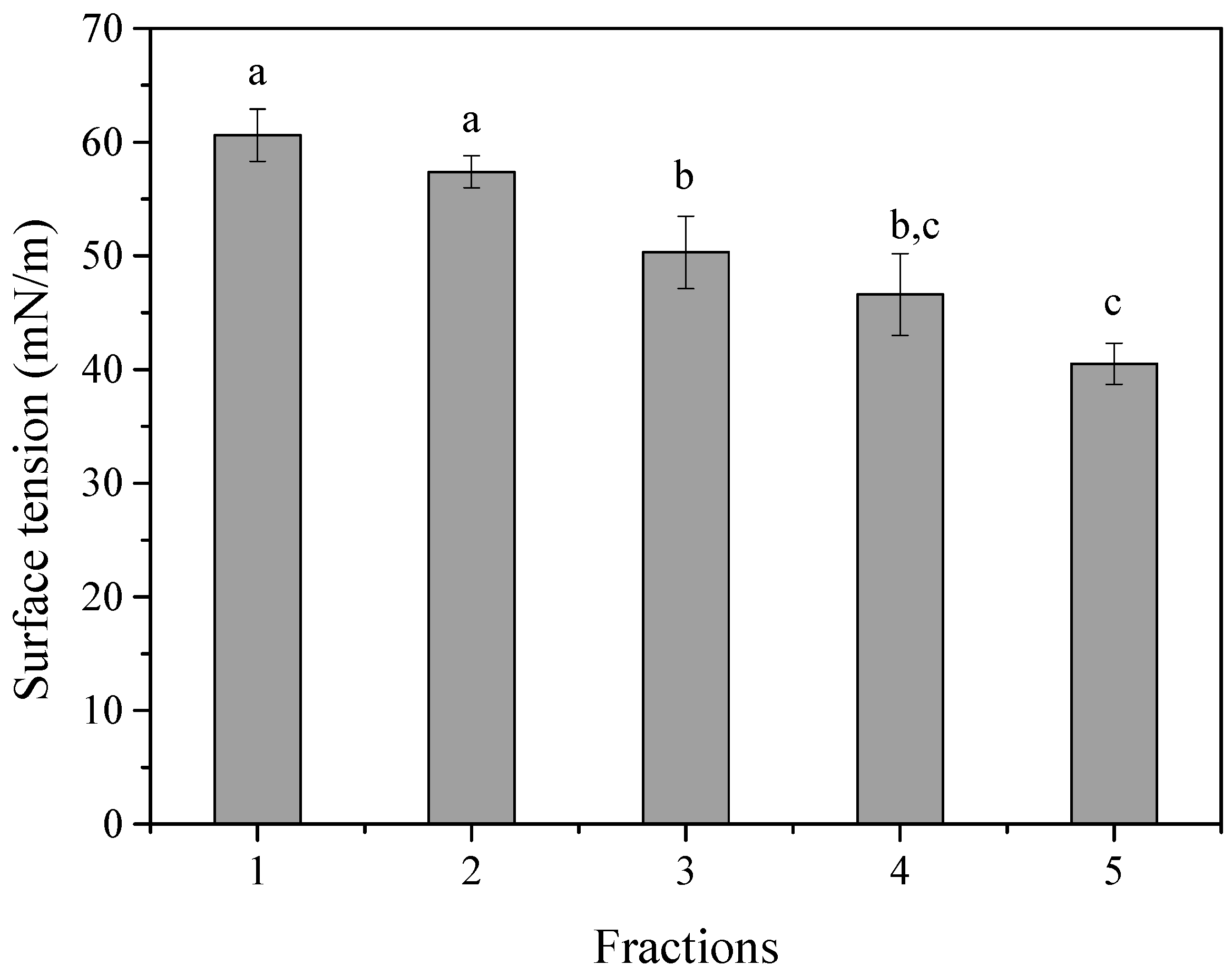

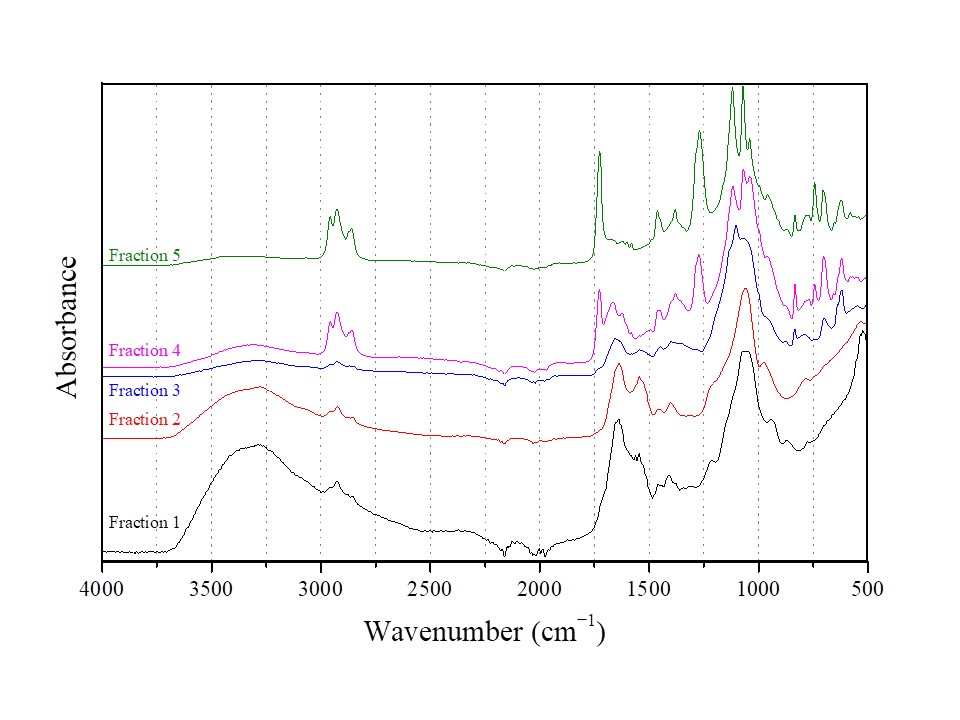

3.4. Fractionation of BS Produced from L. fermentum ACA-DC 0183

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| BS | Biosurfactants |

| CB-BS | Cell-bound biosurfactants |

| CW | Cheese whey |

| DAD | Diode Array Detector |

| FAN | Free amino nitrogen |

| FID | Flame Ionization Detector |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| MRS | De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe |

| RP-HPLC | Reverse-phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| ST | Surface tension |

| TDW | Total dry weight |

| TLC | Thin-Layer Chromatography |

References

- da Silva, P.F.F.; da Silva, R.R.; Sarubbo, L.A.; Guerra, J.M.C. Production and optimization of biosurfactant properties using Candida mogii and Licuri oil (Syagrus coronata). Foods 2024, 13, 4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, V.M.; Mendonça, C.M.N.; Silva, F.V.S.; Marguet, E.R.; Vallejo, M.; Converti, A.; Varani, A.M.; Gliemmo, M.F.; Campos, C.A.; Oliveira, R.P.S. Characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Tw226 strain and its use for the production of a new membrane-bound biosurfactant. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 363, 119889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banat, I.M.; Franzetti, A.; Gandolfi, I.; Bestetti, G.; Martinotti, M.G.; Fracchia, L.; Smyth, T.J.; Marchant, R. Microbial biosurfactants production, applications and future potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavasi, R.; Jayalakshmi, S.; Banat, I.M. Application of biosurfactant produced from peanut oil cake by Lactobacillus delbrueckii in biodegradation of crude oil. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3366–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biselli, A.; Willenbrink, A.L.; Leipnitz, M.; Jupke, A. Development, evaluation, and optimisation of downstream process concepts for rhamnolipids and 3-(3-hydroxyalkanoyloxy)alkanoic acids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 250, 117031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.I.S.; Guerra, J.M.C.; Meira, H.M.; Sarubbo, L.A.; de Luna, J.M. A biosurfactant from Candida bombicola: Its synthesis, characterization, and its application as a food emulsions. Foods 2022, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittisart, P.; Gasaluck, P. Biosurfactant production by Lactobacillus plantarum MGL-8 from mango waste. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 2883–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Saharan, B.S.; Kapil, S. Biosurfactants of probiotic lactic acid bacteria. In Biosurfactants of Lactic Acid Bacteria; SpringerBriefs in Microbiology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 17–29. ISBN 9783319262130. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, B.G.; Guerra, J.M.C.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Production and application prospects in the food industry. Biotechnol. Prog. 2020, 36, e3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadnia, A.; Moosavi-nasab, M.; Tiwari, B.K.; Setoodeh, P. Lactobacillus plantarum- derived biosurfactant: Ultrasound-induced production and characterization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 65, 105037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, V.M.; Gliemmo, M.F.; Vallejo, M.; González, M.d.C.G.; Rodríguez, M.d.C.A.; Campos, C.A. Use of the Glycolipopeptid Biosurfactant Produced by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Tw226 to Formulate Functional Cinnamon Bark Essential Oil Emulsions. Foods 2025, 14, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachrimanidou, V.; Alimpoumpa, D.; Papadaki, A.; Lappa, I.; Alexopoulos, K.; Kopsahelis, N. Cheese whey utilization for biosurfactant production: Evaluation of bioprocessing strategies using novel Lactobacillus strains. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 4621–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachrimanidou, V.; Papadaki, A.; Lappa, I.; Papastergiou, S.; Kleisiari, D.; Kopsahelis, N. Biosurfactant production from Lactobacilli: An insight on the interpretation of prevailing assessment methods. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachrimanidou, V.; Alexandri, M.; Nascimento, M.F.; Alimpoumpa, D.; Torres Faria, N.; Papadaki, A.; Castelo Ferreira, F.; Kopsahelis, N. Lactobacilli and Moesziomyces biosurfactants: Toward a closed-loop approach for the dairy industry. Fermentation 2022, 8, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučurović, D.; Bajić, B.; Trivunović, Z.; Dodić, J.; Zeljko, M.; Jevtić-Mučibabić, R.; Dodić, S. Biotechnological Utilization of Agro-Industrial Residues and By-Products—Sustainable Production of Biosurfactants. Foods 2024, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouafo, H.T.; Sokamte, A.T.; Mbawala, A.; Ndjouenkeu, R.; Devappa, S. Biosurfactants from lactic acid bacteria: A critical review on production, extraction, structural characterization and food application. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouafo, H.T.; Mbawala, A.; Somashekar, D.; Tchougang, H.M.; Harohally, N.V.; Ndjouenkeu, R. Biological properties and structural characterization of a novel rhamnolipid like-biosurfactants produced by Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei TM1B. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2021, 68, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, S.; Rajendran, D.S.; Kumar, P.S.; Vo, D.V.N.; Vaidyanathan, V.K. Extraction, purification and applications of biosurfactants based on microbial-derived glycolipids and lipopeptides: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 949–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachrimanidou, V.; Alexandri, M.; Alimpoumpa, D.; Papadaki, A.; Lappa, I.K.; Kopsahelis, N. Biosurfactants production by LAB and emerging applications. In Lactic Acid Bacteria as Cell Factories; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 335–366. [Google Scholar]

- Mouafo, H.T.; Sokamte, A.T.; Manet, L.; Mbarga, A.J.M.; Nadezdha, S.; Devappa, S.; Mbawala, A. Biofilm inhibition, antibacterial and antiadhesive properties of a novel biosurfactant from Lactobacillus paracasei N2 against multi-antibiotics-resistant pathogens isolated from braised fish. Fermentation 2023, 9, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, B.H.; Ramesh, C.; Mallappa, R.H. Characterization of biosurfactants derived from probiotic lactic acid bacteria against methicillin-resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Lwt 2021, 151, 112195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumari, P.; Mani, K. Structural characterization of a novel xylolipid biosurfactant from Lactococcus lactis and analysis of antibacterial activity against multi-drug resistant pathogens. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8851–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvageau, J.; Ryan, J.; Lagutin, K.; Sims, I.M.; Stocker, B.L.; Timmer, M.S.M. Isolation and structural characterisation of the major glycolipids from Lactobacillus plantarum. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 357, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.F.; Mulvihill, D.M. Proteins recovered from acid whey/skim milk mixtures heated at alkaline pH values. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 1988, 41, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grufferty, M.B.; Mulvihill, D.M. Proteins recovered from milks heated at alkaline pH values. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 1987, 40, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Saharan, B.S.; Chauhan, N.; Procha, S.; Lal, S. Isolation and functional characterization of novel biosurfactant produced by Enterococcus faecium. Springerplus 2015, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, D.; Bhagowati, P.; Gogoi, P.; Bordoloi, N.K.; Rafay, A.; Dolui, S.K.; Mukherjee, A.K. Structural and physico-chemical characterization of a dirhamnolipid biosurfactant purified from: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Application of crude biosurfactant in enhanced oil recovery. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 70669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, A.N.; Lymperatou, A.; Skiadas, I.; Kumar, M.; Srivastava, P. Structural and functional characterization of a novel biosurfactant from Bacillus sp. IITD106. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouafo, T.H.; Mbawala, A.; Ndjouenkeu, R. Effect of different carbon sources on biosurfactants’ production by three strains of Lactobacillus spp. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5034783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, E.A.E.; Ahmed, H.A.E.; Abo Saif, F.A.A. Characterization of low-cost glycolipoprotein biosurfactant produced by Lactobacillus plantarum 60 FHE isolated from cheese samples using food wastes through response surface methodology and its potential as antimicrobial, antiviral, and anticancer activi. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 170, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, S. The EBC-ninhydrin method for determination of free alpha amino nitrogen. J. Inst. Brew. 1973, 79, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Pruthi, V.; Singh, R.P.; Pruthi, P.A. Synergistic effect of fermentable and non-fermentable carbon sources enhances TAG accumulation in oleaginous yeast Rhodosporidium kratochvilovae HIMPA1. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 188, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, S.; Szłyk, E.; Jastrzębska, A. Simple extraction procedure for free amino acids determination in selected gluten-free flour samples. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Gao, Z.; Xu, M.; Ohm, J.B.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. The impact of hempseed dehulling on chemical composition, structure properties and aromatic profile of hemp protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 106, 105889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsia, A.; Papadaki, A.; Papapostolou, H.; Christopoulou, N.M.; Kopsahelis, N. Effect of solubilization pH and dehulling on hempseed protein recovery: Chemical characterization, physical properties, and preliminary study of carbon dots synthesis from residual solids. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 45, 102005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska-Widdrat, A.; Babor, M.; Höhne, M.M.C.; Alexandri, M.; López-Gómez, J.P.; Venus, J. A mathematical model-based evaluation of yeast extract’s effects on microbial growth and substrate consumption for lactic acid production by Bacillus coagulans. Process Biochem. 2024, 146, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, S.; Kuenz, A.; Prüße, U. Nutritional requirements and the impact of yeast extract on the d-lactic acid production by Sporolactobacillus inulinus. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 4633–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, S.; Liu, G.; Fan, X.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, A.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, K. The nutrient requirements of Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5 and their application to fermented milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeboah, P.J.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Krastanov, A. A review of fermentation and the nutritional requirements for effective growth media for lactic acid bacteria. Food Sci. Appl. Biotechnol. 2023, 6, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.M.; Yang, F.; Iannotti, E.L. The effect of soy protein hydrolyzates on fermentation by Lactobacillus amylovorus. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, M.C.; Restrepo, M.A.F.; Duque, F.L.G.; Díaz, J.C.Q. Production, characterization and kinetic model of biosurfactant produced by lactic acid bacteria. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 53, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.C.; Oliveira de Souza de Azevedo, P.; Domínguez, J.M.; Converti, A.; Pinheiro De Souza Oliveira, R. Influence of temperature and pH on the production of biosurfactant, bacteriocin and lactic acid by Lactococcus lactis CECT-4434. CyTA J. Food 2017, 15, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Setoodeh, P.; Mesbahi, G.; Yousefi, G. Biosurfactant production by lactic acid bacterium Pediococcus dextrinicus SHU1593 grown on different carbon sources: Strain screening followed by product characterization. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudiña, E.J.; Rodrigues, A.I.; Alves, E.; Domingues, M.R.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rodrigues, L.R. Bioconversion of agro-industrial by-products in rhamnolipids toward applications in enhanced oil recovery and bioremediation. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 177, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Housseiny, G.S.; Aboshanab, K.M.; Aboulwafa, M.M.; Hassouna, N.A. Structural and physicochemical characterization of rhamnolipids produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa P6. AMB Express 2020, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouafo, H.T.; Mbawala, A.; Tanaji, K.; Somashekar, D.; Ndjouenkeu, R. Improvement of the shelf life of raw ground goat meat by using biosurfactants produced by lactobacilli strains as biopreservatives. Lwt 2020, 133, 110071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecino, X.; Rodríguez-López, L.; Gudiña, E.J.; Cruz, J.M.; Moldes, A.B.; Rodrigues, L.R. Vineyard pruning waste as an alternative carbon source to produce novel biosurfactants by Lactobacillus paracasei. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 55, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.; Kaur, S.; Dwibedi, V.; Albadrani, G.M.; Al-Ghadi, M.Q.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Unveiling the antimicrobial and antibiofilm potential of biosurfactant produced by newly isolated Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain 1625. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1459388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-janabi, M.Z.J.; Al-dulaimy, W.Y.M.; Abdulateef, M.H.; Ahmed, A.A.; Kadhom, M. Comparative cytotoxicity of a glycolipopeptide biosurfactant from Lactobacillus plantarum and its derived silver nanoparticles against breast cancer cells. Med. Microecol. 2025, 25, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Khan, M.R.; Mukherjee, A.K. Statistical optimization of production and characterization of biosurfactant produced by Lactobacillus plantarum JBC5 strain in a ghee (clarified butter) medium: Assessment of its antimicrobial activity and stain removal property. Process Biochem. 2025, 158, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, C.J.; de Andrade, L.M.; Rocco, S.A.; Sforça, M.L.; Pastore, G.M.; Jauregi, P. A novel approach for the production and purification of mannosylerythritol lipids (MEL) by Pseudozyma tsukubaensis using cassava wastewater as substrate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 180, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Singha, L.P.; Shukla, P. Biotechnological potential of microbial bio-surfactants, their significance, and diverse applications. FEMS Microbes 2023, 4, xtad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciurko, D.; Chebbi, A.; Kruszelnicki, M.; Czapor-Irzabek, H.; Urbanek, A.K.; Polowczyk, I.; Franzetti, A.; Janek, T. Production and characterization of lipopeptide biosurfactant from a new strain of Pseudomonas antarctica 28E using crude glycerol as a carbon source. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 24129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, F. Lipopeptide biosurfactants of Pseudomonas fragi showed intraspecific specificity to their biological traits. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Saharan, B.S.; Chauhan, N.; Bansal, A.; Procha, S. Production and structural characterization of Lactobacillus helveticus derived biosurfactant. Sci. World J. 2014, 1, 493548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Vien, D.; Colthup, N.B.; Fateley, W.G.; Grasselli, J.G. The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, B.H. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Pereira, L.; Pocheville, A.; Angulo, I.; Paseiro-Losada, P.; Cruz, J.M. Fractionation and purification of bioactive compounds obtained from a brewery waste stream. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 408491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composition | Retention Time (min) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| caproic acid (C6:0) | 6.592 | 0.10 |

| caprylic acid (C8:0) | 13.690 | 0.34 |

| decanoic acid (C10:0) | 22.721 | 2.22 |

| lauric acid (C12:0) | 31.596 | 1.38 |

| myristic acid (C14:0) | 39.745 | 4.25 |

| pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) | 43.539 | 0.46 |

| palmitic acid (C16:0) | 47.191 | 27.89 |

| palmitoleic acid (C16:1) | 48.963 | 1.23 |

| stearic acid (C18:0) | 53.968 | 11.19 |

| oleic acid (C18:1-cis (n9)) | 55.356 | 18.67 |

| linoleic acid (C18:2-cis (n6)) | 57.851 | 1.34 |

| arachidic acid (C20:0) | 60.204 | 0.27 |

| α-linolenic acid (C18:3 (ω-3)) | 60.808 | 0.28 |

| eicosenoic acid (C20:1) | 61.453 | 0.37 |

| henicosanoic acid (C21:0) | 63.091 | 1.04 |

| eicosadienoic acid (C20:2) | 63.678 | 0.55 |

| docosanoic acid (C22:0) | 66.016 | 0.16 |

| eicosapentenoic acid (C20:5) | 71.591 | 0.35 |

| tetracosanoic acid (C24:0) | 72.581 | 0.27 |

| docosahexenoic acid (C22:6) | 78.523 | 0.50 |

| Amino Acid | mg/g BS |

|---|---|

| L-Aspartic acid | 6.12 ± 0.11 |

| L-Glutamic acid | 12.25 ± 0.32 |

| L-Serine | 3.06 ± 0.05 |

| L-Histidine | 9.26 ± 0.26 |

| Glycine | 2.11 ± 0.01 |

| L-Threonine | 3.72 ± 0.19 |

| L-Arginine | 20.83 ± 0.95 |

| L-Alanine | 1.75 ± 0.03 |

| L-Tyrosine | 2.85 ± 0.11 |

| L-Cystine | 6.80 ± 0.04 |

| L-Valine | 4.46 ±0.02 |

| L-Methionine | 2.87 ± 0.04 |

| L-Phenylalanine | 3.57 ± 0.12 |

| L-Isoleucine | 3.32 ± 0.07 |

| L-Leucine | 5.13 ± 0.06 |

| L-Lysine | 6.45 ± 0.02 |

| L-Proline | 15.14 ± 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alimpoumpa, D.; Papapostolou, H.; Alexandri, M.; Kachrimanidou, V.; Kopsahelis, N. Fractionation and Chemical Characterization of Cell-Bound Biosurfactants Produced by a Novel Limosilactobacillus fermentum Strain via Cheese Whey Valorization. Foods 2025, 14, 4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244342

Alimpoumpa D, Papapostolou H, Alexandri M, Kachrimanidou V, Kopsahelis N. Fractionation and Chemical Characterization of Cell-Bound Biosurfactants Produced by a Novel Limosilactobacillus fermentum Strain via Cheese Whey Valorization. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244342

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlimpoumpa, Dimitra, Harris Papapostolou, Maria Alexandri, Vasiliki Kachrimanidou, and Nikolaos Kopsahelis. 2025. "Fractionation and Chemical Characterization of Cell-Bound Biosurfactants Produced by a Novel Limosilactobacillus fermentum Strain via Cheese Whey Valorization" Foods 14, no. 24: 4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244342

APA StyleAlimpoumpa, D., Papapostolou, H., Alexandri, M., Kachrimanidou, V., & Kopsahelis, N. (2025). Fractionation and Chemical Characterization of Cell-Bound Biosurfactants Produced by a Novel Limosilactobacillus fermentum Strain via Cheese Whey Valorization. Foods, 14(24), 4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244342