Effect of Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties, Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant Activity and Functional Properties of Alfalfa Protein Concentrates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Plant Material

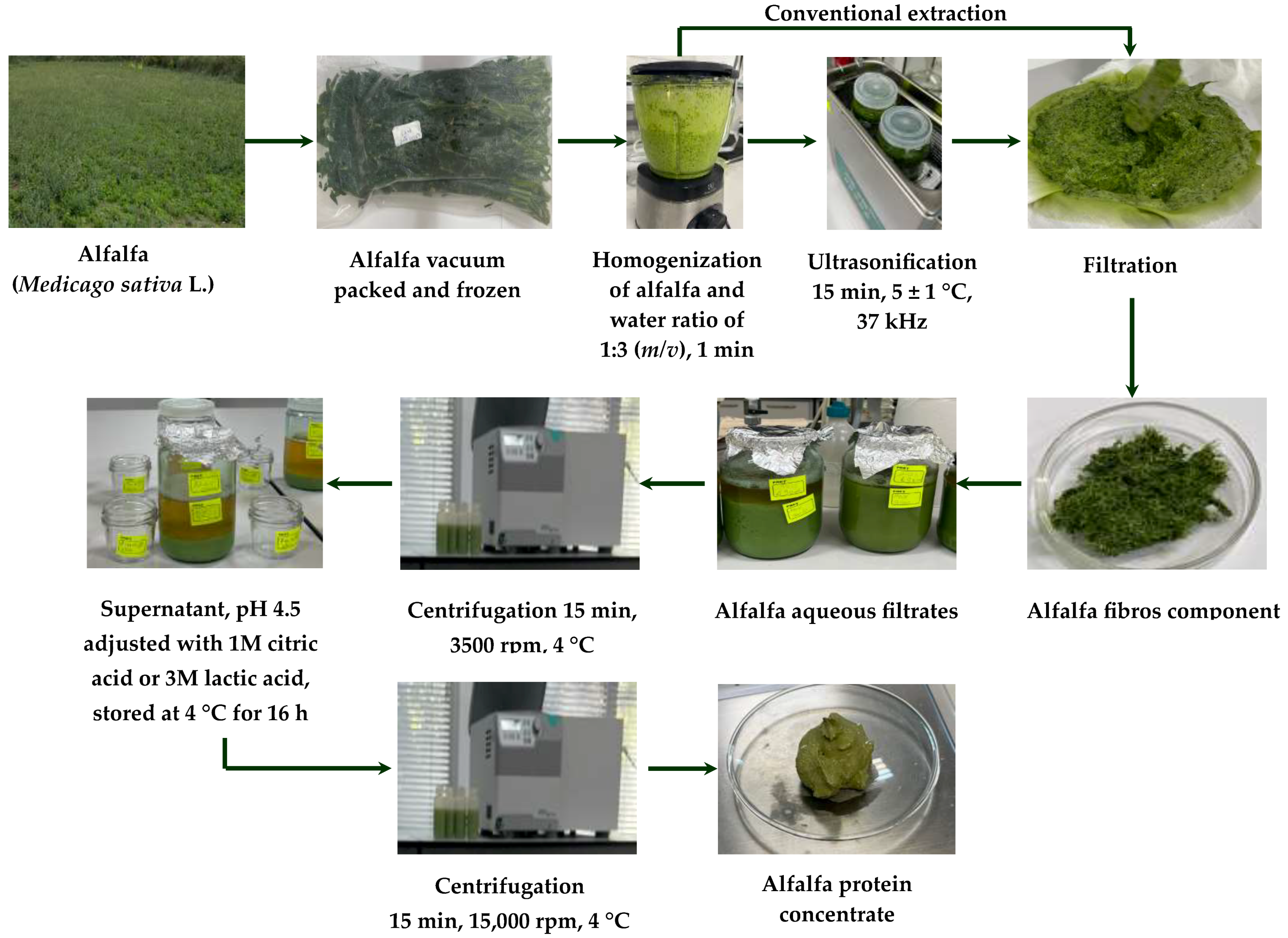

2.2. Extraction of APC from Medicago sativa L.

2.3. Physicochemical Analysis

2.3.1. Amino Acid Profile

2.3.2. Mineral Profile

2.3.3. Color Parameters

2.4. Digestibility of Proteins

2.5. Analysis of Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Content

2.6. Total Polyphenols and Flavonoids

2.7. Determination of Radical-Scavenging Activity

2.8. Foaming Capacity and Foam Stability

2.9. Emulsifying Activity and Emulsion Stability

2.10. Texture Profile Analysis

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Frozen Alfalfa

3.2. Influence of Extraction Method and Type of Acid Applied in Isoelectric Sedimentation on Physicochemical Indices, CIELab Color Parameters, BAC and AA of APC

3.2.1. Impact of Extraction Method on the Protein Concentrates Physicochemical Indices

3.2.2. Influence of Extraction Method on CIELab Color Parameters of APC

3.2.3. Influence of Extraction Methods on Phytochemical Content and Antioxidant Activity of APC

3.2.4. Influence of Extraction Methods on Textural and Functional Properties of APC

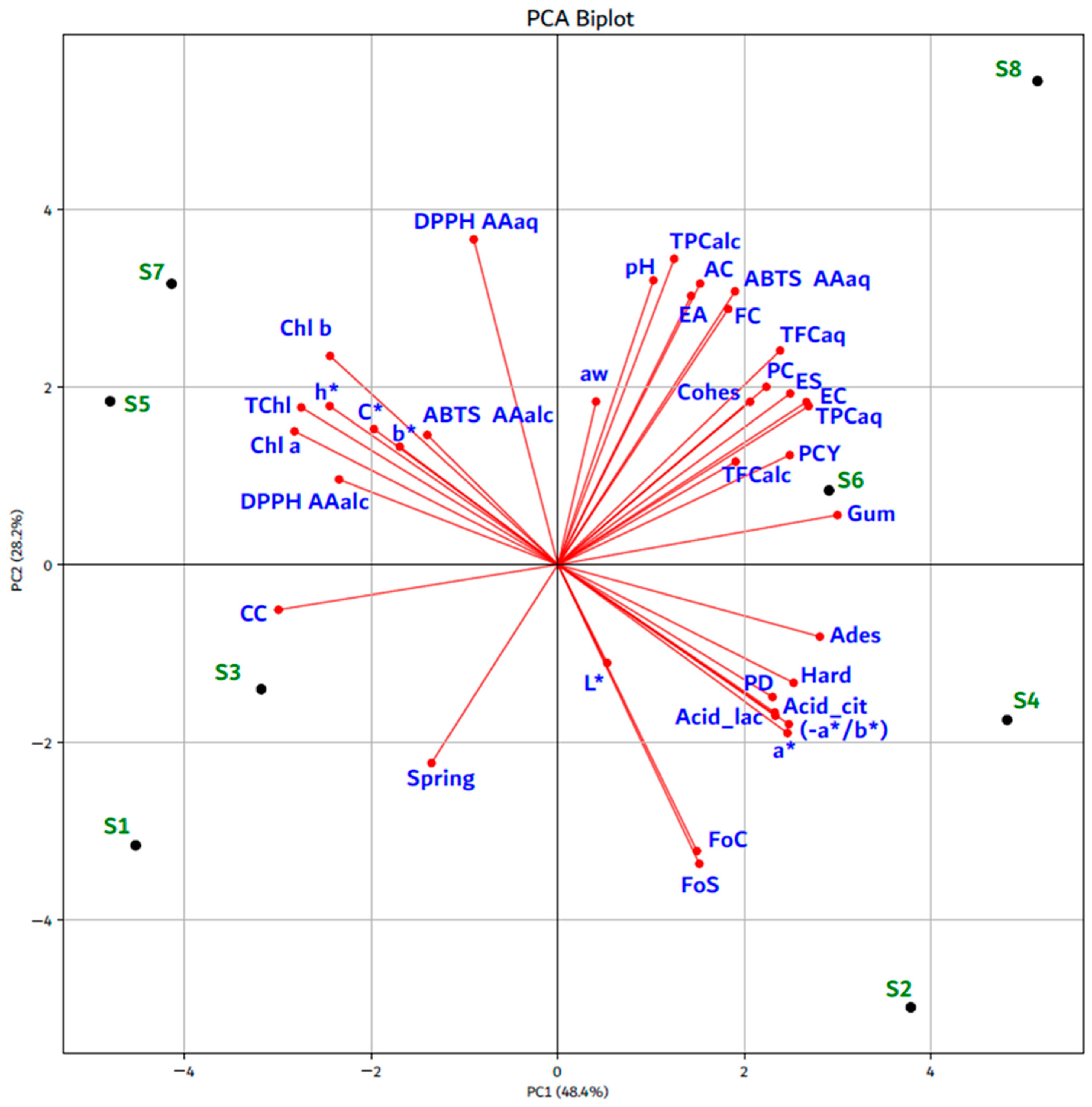

3.3. Relationships Between Physicochemical Characteristics, CIELab Color Parameters, Biologically Active Compounds, Texture Profile, and Functional Properties in APC

4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

6. Future Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Espinosa-Marrón, A.; Adams, K.; Sinno, L.; Cantu-Aldana, A.; Tamez, M.; Marrero, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Mattei, J. Environmental Impact of Animal-Based Food Production and the Feasibility of a Shift Toward Sustainable Plant-Based Diets in the United States. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 841106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, B.; Gastal, F.; Louarn, G.; Badenhausser, I.; Annicchiarico, P.; Crocq, G.; Le Chatelier, D.; Guillemot, E.; Emile, J.-C. Lucerne (Alfalfa) in European Cropping Systems. In Legumes in Cropping Systems; Murphy-Bokern, D., Stoddard, F.L., Watson, C.A., Eds.; CAB International: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 168–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kromus, S.; Kamm, B.; Kamm, M.; Fowler, P.; Narodoslawsky, M. Green Biorefineries: The Green Biorefinery Concept—Fundamentals and Potential. In Biorefineries—Industrial Processes and Products: Status Quo and Future Directions; Kamm, B., Gruber, R., Kamm, M., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; pp. 253–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgaru, V.; Mazur, M.; Netreba, N.; Paiu, S.; Dragancea, V.; Gurev, A.; Sturza, R.; Şensoy, İ.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A. Characterization of Plant-Based Raw Materials Used in Meat Analog Manufacture. Foods 2025, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, M.; Morley, T.; Rau, M.L.; Muller, M.; van Ittersum, M.K.; van Wijk, M.; Reidsma, P. A Meta-Analysis of Projected Global Food Demand and Population at Risk of Hunger for the Period 2010–2050. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prywes, N.; Phillips, N.R.; Tuck, O.T.; Valentin-Alvarado, L.E.; Savage, D.F. Rubisco Function, Evolution and Engineering. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2023, 92, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Orellana Palacios, J.C.; McClements, D.J.; Mahfouzi, M.; Moreno, A. Alfalfa as a Sustainable Source of Plant-Based Food Proteins. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 135, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization; United Nations University. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series 935; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) Scientific Opinion on the Safety of ‘Alfalfa Protein Concentrate’ as Food. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoop, A.; Pillai, P.K.; Nickerson, M.; Ragavan, K. Plant Leaf Proteins for Food Applications: Opportunities and Challenges. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 473–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinow, M.R.; McLaughlin, P.; Stafford, C.; Livingston, A.L.; Kohler, G.O. Alfalfa Saponins and Alfalfa Seeds: Dietary Effects in Cholesterol-Fed Rabbits. Atherosclerosis 1980, 37, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawiwan, P.; Quek, S.Y. Physicochemical and Functional Attributes of RuBisCo-Enriched Brassicaceae Leaf Protein Concentrates. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 151, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.; Andersen, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Hobley, T.J. Scale-Up of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) Protein Recovery Using Screw Presses. Foods 2022, 11, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.H.; Lübeck, M.; Møller, A.H.; Dalsgaard, T.K. Protein Recovery and Quality of Alfalfa Extracts Obtained by Acid Precipitation and Fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 19, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Trigueros, E. Evaluating the Sustainability of Emerging Extraction Technologies for Valorization of Food Waste: Microwave, Ultrasound, Enzyme-Assisted, and Supercritical Fluid Extraction. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Method for Extracting Alfalfa Leaf Protein by Ultrasonic-Assisted Enzyme Process. Patent WO2012150421A1, 8 November 2012. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN102351944B/en (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Badjona, A.; Bradshaw, R.; Millman, C.; Howarth, M.; Dubey, B. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of faba bean protein isolate: Structural, functional, and thermal properties. Part 2/2. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 110, 107030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Yao, D.; Xia, S.; Cheong, L.; Tu, M. Recent progress in plant-based proteins: From extraction and modification methods to applications in the food industry. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadidi, M.; Khaksar, F.B.; Pagán, J.; Ibarz, A. Application of Ultrasound–Ultrafiltration–Assisted Alkaline Isoelectric Precipitation (UUAAIP) Technique for Producing Alfalfa Protein Isolate for Human Consumption: Optimization, Comparison, Physicochemical, and Functional Properties. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Xu, L.; Ma, H. An efficient ultrasound-assisted extraction method of pea protein and its effect on protein functional properties and biological activities. LWT 2020, 127, 109348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdi, T.S.; Setiowati, A.D.; Ningrum, A. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of Spirulina platensis protein: Physico-chemical characteristic and techno-functional properties. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5474–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demesa, A.G.; Saavala, S.; Pöysä, M.; Koiranen, T. Overview and Toxicity Assessment of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Natural Ingredients from Plants. Foods 2024, 13, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law No. 150 of 14 May 2004 on Food and Feed Safety. Romania. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/public/DetaliiDocument/52134 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Bulgaru, V.; Şensoy, İ.; Netreba, N.; Gurev, A.; Altanlar, U.; Paiu, S.; Dragancea, V.; Sturza, R.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A. Qualitative and Antioxidant Evaluation of High-Moisture Plant-Based Meat Analogs Obtained by Extrusion. Foods 2025, 14, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgaru, V.; Netreba, N.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A. Pre-Treatment of Vegetable Raw Materials (Sorghum oryzoidum) for Use in Meat Analog Manufacture. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, N.; Karadeniz, F.; Burdurlu, S.H. Effect of pH on Chlorophyll Degradation and Colour Loss in Blanched Green Peas. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghendov-Mosanu, A.; Netreba, N.; Balan, G.; Cojocari, D.; Boestean, O.; Bulgaru, V.; Gurev, A.; Popescu, L.; Deseatnicova, O.; Resitca, V.; et al. Effect of Bioactive Compounds from Pumpkin Powder on the Quality and Textural Properties of Shortbread Cookies. Foods 2023, 12, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgaru, V.; Gurev, A.; Baerle, A.; Dragancea, V.; Balan, G.; Cojocari, D.; Sturza, R.; Soran, M.-L.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A. Phytochemical, Antimicrobial, and Antioxidant Activity of Different Extracts from Frozen, Freeze-Dried, and Oven-Dried Jostaberries Grown in Moldova. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristea, E.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A.; Pintea, A.; Sturza, R.; Patras, A. Color Stability and Antioxidant Capacity of Crataegus monogyna Jacq. Berry Extract Influenced by Different Conditions. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketnawa, S.; Ogawa, Y. In Vitro Protein Digestibility and Biochemical Characteristics of Soaked, Boiled and Fermented Soybeans. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khem, S. Development of Model Fermented Fish Sausage from New Zealand Marine Species: A Thesis Submitted to AUT University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (MAppSc); Auckland University of Technology: Auckland, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sumanta, N.; Haque, C.I.; Nishika, J.; Suprakash, R. Spectrophotometric Analysis of Chlorophylls and Carotenoids from Commonly Grown Fern Species by Using Various Extracting Solvents. Res. J. Chem. Sci. 2014, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyahya, A.; Dakka, N.; Talbaoui, A.; Moussaoui, N.E.; Abrini, J.; Bakri, Y. Phenolic Contents and Antiradical Capacity of Vegetable Oil from Pistacia lentiscus (L.). J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2018, 9, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, L.; Cesco, T.; Gurev, A.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A.; Sturza, R.; Tarna, R. Impact of Apple Pomace Powder on the Bioactivity, and the Sensory and Textural Characteristics of Yogurt. Foods 2022, 11, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolic Compounds with Phosphomolybdic–Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulpriya, K.; Packia Lincy, M.; Tresina Soris, P.; Veerabahu Ramasamy, M. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic and Total Flavonoid Contents of Aerial Part Extracts of Daphniphyllum neilgherrense (Wt.) Rosenth. Ethnopharm. J. Biol. Innov. 2015, 4, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Arnao, M.B.; Cano, A.; Alcolea, J.F.; Acosta, M. Estimation of Free Radical-Quenching Activity of Leaf Pigment Extracts. Phytochem. Anal. 2001, 12, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Medina, A.; Jiménez-Islas, H.; Dendooven, L.; Patiño-Herrera, R.; González-Alatorre, G.; Escamilla-Silva, E.M. Emulsifying and Foaming Capacity and Emulsion and Foam Stability of Sesame Protein Concentrates. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Kinsella, J.E. Functional Properties of Novel Proteins: Alfalfa Leaf Protein. J. Food Sci. 1976, 41, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texture Technologies. Overview of Texture Analysis. Available online: https://texturetechnologies.com/resources/texture-profile-analysis (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Putnam, D.; Orloff, S.N. Forage Crops. In Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems; Van Alfen, N.K., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 381–405. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, P.; Edwards, R.A.; Greenhalgh, J.F.D.; Morgan, C.A.; Sinclair, L.A.; Wilkinson, R.G. Animal Nutrition, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Marković, J.; Radović, J.; Lugić, Z.; Sokolović, D. The Effect of Development Stage on Chemical Composition of Alfalfa Leaf and Stem. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2007, 23, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Liu, B.; Zhao, S.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Shi, Y.; Sun, H.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Nutritional Value and Contaminants of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in China. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1539462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wang, D.; Lu, N.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Cao, Z.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; Yu, X.; Shao, W.; et al. Analysis of Chemical Composition, Amino Acid Content, and Rumen Degradation Characteristics of Six Organic Feeds. Animals 2022, 12, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, K.V. Comparative Study of Acidity Status in Some Wild Vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 5, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kung, L.; Shaver, R.; Grant, R.; Schmidt, R. Silage Review: Interpretation of Chemical, Microbial, and Organoleptic Components of Silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4020–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.V., Jr. Quality Control: Water Activity Considerations for Beyond-Use Dates. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2024, 28, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buxton, D.R.; Redfearn, D.D. Plant Limitations to Fiber Digestion and Utilization. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 814S–818S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.R.; Pinchak, W.E.; Hume, M.E.; Anderson, R.C. Effects of Condensed Tannins Supplementation on Animal Performance, Phylogenetic Microbial Changes, and In Vitro Methane Emissions in Steers Grazing Winter Wheat. Animals 2021, 11, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Song, Z.; Ma, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.; Ding, C.; Chen, H.; Zhao, S. Study on the Drying Characteristics and Physicochemical Properties of Alfalfa under High-Voltage Discharge Plasma. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Çetin, N.; Çiftci, B.; Taşan, M.; Durgut, M.; Aksu, H. Comparison of Drying Methods for Biochemical Composition, Energy Aspects, and Color Properties of Alfalfa Hay. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 10331–10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, W.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cai, T.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chang, C.; Yin, Q.; Jiang, X.; et al. Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal New Insights into Nutritional Quality Changes of Alfalfa Leaves during the Flowering Period. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 995031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiñones-Muñoz, T.A.; Villanueva-Rodríguez, S.J.; Torruco-Uco, J.G. Nutraceutical Properties of Medicago sativa L., Agave spp., Zea mays L. and Avena sativa L.: A Review of Metabolites and Mechanisms. Metabolites 2022, 12, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, E.; Oskoueian, E.; Oskoueian, A.; Omidvar, V.; Hendra, R.; Nazeran, H. Insight into the Functional and Medicinal Properties of Medicago sativa (Alfalfa) Leaves Extract. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Raeeszadeh, M.; Beheshtipour, J.; Jamali, R.; Akbari, A. The Antioxidant Properties of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and Its Biochemical, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Pathological Effects on Nicotine-Induced Oxidative Stress in the Rat Liver. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2691577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufan, W.; Okla, M.K.; Salamatullah, A.; Hayat, K.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.A.; Al-Amri, S.S. Seasonal Variation in Yield, Nutritive Value, and Antioxidant Capacity of Leaves of Alfalfa Plants Grown in Arid Climate of Saudi Arabia. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 81, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, G.; Assefa, G.; Feyissa, F.; Mengistu, A.; Tekletsadik, T.; Minta, M.; Tesfaye, M. Biomass Yield Potential and Herbage Quality of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Genotypes in the Central Highland of Ethiopia. Int. J. Res. Stud. Agric. Sci. 2017, 3, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homolka, P.; Koukolová, V.; Němec, Z.; Mudřík, Z.; Hučko, B.; Sales, J. Amino Acid Contents and Intestinal Digestibility of Lucerne in Ruminants as Influenced by Growth Stage. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 53, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.-S.; Tian, Y.-J.; He, Y.-Z.; Li, L.; Hu, S.-Q.; Li, B. Optimisation of Ultrasonic-Assisted Protein Extraction from Brewer’s Spent Grain. Czech J. Food Sci. 2010, 28, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, M.; Sit, N. Application of Ultrasound in Combination with Other Technologies in Food Processing: A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 73, 105506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firdaous, L.; Dhulster, P.; Amiot, J.; Gaudreau, A.; Lecouturier, D.; Kapel, R.; Lutin, F.; Vézina, L.-P.; Bazinet, L. Concentration and Selective Separation of Bioactive Peptides from an Alfalfa White Protein Hydrolysate by Electrodialysis with Ultrafiltration Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 329, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Garcia, A.; Martinez, C.; Gonzalez, G. Effects of Freezing and pH of Alfalfa Leaf Juice upon the Recovery of Chloroplastic Protein Concentrates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1988, 36, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nynäs, A.-L.; Newson, W.R.; Johansson, E. Protein Fractionation of Green Leaves as an Underutilized Food Source—Protein Yield and the Effect of Process Parameters. Foods 2021, 10, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paker, I.; Jaczynski, J.; Matak, K.E. Calcium Hydroxide as a Processing Base in Alkali-Aided pH-Shift Protein Recovery Process: Calcium Hydroxide in a pH-Shift Protein Recovery Process. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Shen, P.; Lan, Y.; Cui, L.; Ohm, J.B.; Chen, B.; Rao, J. Effect of Alkaline Extraction pH on Structure Properties, Solubility, and Beany Flavor of Yellow Pea Protein Isolate. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 109045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, A.S.; Kashyap, P.; Thakur, M. Effect of Extraction Methods on Functional Properties of Plant Proteins: A Review. eFood 2024, 5, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña, M.; Calahorro, M.; Eim, V.; Rosselló, C.; Simal, S. Measurement of Microstructural Changes Promoted by Ultrasound Application on Plant Materials with Different Porosity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 88, 106087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirón-Mérida, V.A.; Soria-Hernández, C.; Richards-Chávez, A.; Ochoa-García, J.C.; Rodríguez-López, J.L.; Chuck-Hernández, C. The Effect of Ultrasound on the Extraction and Functionality of Proteins from Duckweed (Lemna minor). Molecules 2024, 29, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Faro, E.; Salerno, T.; Montevecchi, G.; Fava, P. Mitigation of Acrylamide Content in Biscuits through Combined Physical and Chemical Strategies. Foods 2022, 11, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilani, G.S.; Xiao, C.W.; Cockell, K.A. Impact of Antinutritional Factors in Food Proteins on the Digestibility of Protein and the Bioavailability of Amino Acids and on Protein Quality. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S315–S332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanambell, H.; Danielsen, M.; Devold, T.G.; Møller, A.H.; Dalsgaard, T.K. In Vitro Protein Digestibility of RuBisCO from Alfalfa Obtained from Different Processing Histories: Insights from Free N-Terminal and Mass Spectrometry Study. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carail, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Meullemiestre, A.; Chemat, F.; Caris-Veyrat, C. Effects of High Power Ultrasound on All-E-β-Carotene: Newly Formed Compounds Analysis by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 26, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidmose, U.; Edelenbos, M.; Christensen, L.P.; Hegelund, E. Chromatographic Determination of Changes in Pigments in Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) during Processing. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2005, 43, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Guo, J.; Ouyang, L.; Xia, Y.; Huang, X.; Pang, X. Correlation of Leaf Senescence and Gene Expression/Activities of Chlorophyll Degradation Enzymes in Harvested Chinese Flowering Cabbage (Brassica rapa var. parachinensis). J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 2081–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubert, C.; Bailey, G. Isolation of Chlorophylls a and b from Spinach by Counter-Current Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1140, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kut, K.; Bartosz, G.; Sadowska-Bartosz, I. Denaturation and Digestion Increase the Antioxidant Capacity of Proteins. Processes 2023, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Song, K.; Meng, L. Antioxidant Function and Application of Plant-Derived Peptides. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, A.N.; Fernandes, V.S.; Oliveira, W.F.; Gomes, S.R. Degradation Kinetics of Vitamin E during Ultrasound Application and the Adjustment in Avocado Purée by Tocopherol Acetate Addition. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, D.; Viljevac Vuletić, M.; Andrić, L.; Balićević, R.; Kovačević Babić, M.; Tucak, M. Characterization of forage quality, phenolic profile, and antioxidant activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Plants 2022, 11, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucena, M.E.; Alvarez, S.; Menéndez, C.; Riera, F.A.; Alvarez, R. α-Lactalbumin precipitation from commercial whey protein concentrates. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 52, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzeni, C.; Martínez, K.; Zema, P.; Arias, A.; Perez, O.E.; Pilosof, A.M.R. Comparative Study of High Intensity Ultrasound Effects on Food Proteins Functionality. J. Food Eng. 2012, 108, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, O.; Saricaoglu, F.T.; Atalar, I.; Gul, L.B.; Tornuk, F.; Simsek, S. Structural characterization, technofunctional and rheological properties of sesame proteins treated by high-intensity ultrasound. Foods 2023, 12, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Tian, G.; Wang, X.; Deng, W.; Mao, K.; Sang, Y. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the structure and functional properties of mantle proteins from scallops (Patinopecten yessoensis). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 79, 105770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Zhu, C.; Liu, F.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Li, C. Effects of high-intensity ultrasound treatment on functional properties of plum (Pruni domesticae semen) seed protein isolate. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5690–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Manyande, A.; Wang, J. Effect of high-intensity ultrasonic treatment on the physicochemical, structural, rheological, behavioral, and foaming properties of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.)-seed protein isolates. LWT 2022, 155, 112952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gailani, A.; Taylor, M.J.; Zaheer, M.H.; Barker, R. Evaluation of natural organic additives as eco-friendly inhibitors for calcium and magnesium scale formation in water systems. ACS Environ. Au 2024, 4, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Yan, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Effects of pH and ionic strength in calcium on the stability and aeration characteristics of dairy emulsion. Foods 2023, 12, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.; Singh, H. Influence of calcium chloride addition on the properties of emulsions stabilized by whey protein concentrate. Food Hydrocoll. 2000, 14, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.; Murray, B.; Flynn, C.; Norton, I. The Effect of Ultrasound Treatment on the Structural, Physical and Emulsifying Properties of Animal and Vegetable Proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 53, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solvent | Acid of Isoelectric Sedimentation | Conventional Extraction | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (15 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distilled water, pH 5.6 ± 0.01 | Lactic acid | S1 | S2 |

| Citric acid | S3 | S4 | |

| Alkaline aqueous solution, pH 9.0 ± 0.01 | Lactic acid | S5 | S6 |

| Citric acid | S7 | S8 |

| Indices | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Physicochemical Indices | |

| PC, % | 28.63 ± 0.71 |

| AC, % | 11.55 ± 0.11 |

| FC, % | 2.34 ± 0.40 |

| Titratable acidity, % expressed in lactic acid | 0.56 ± 0.013 |

| pH | 5.84 ± 0.01 |

| aw, c.u. | 0.748 ± 0.001 |

| PD, % | 49.37 ± 0.39 |

| CIELab color parameters | |

| L* | 30.30 ± 0.29 |

| a* | −21.99 ± 0.32 |

| b* | 19.40 ± 0.53 |

| −a*/b* | −1.13 ± 0.42 |

| C* | 29.32 ± 0.62 |

| h*, ° | 138.60 ± 0.45 |

| Biologically active compounds | |

| Chl a, mg/100 g DW | 1315.9 ± 2.2 |

| Chl b, mg/100 g DW | 452.8 ± 1.9 |

| TChl, mg/100 g DW | 1768.7 ± 2.0 |

| CC, mg/100 g DW | 10.63 ± 1.7 |

| TPCaq, mg GAE/100 g DW | 2093.6 ± 7.5 a |

| TPCalc, mg GAE/100 g DW | 2583.0 ± 4.9 b |

| TFCaq, mg QE/100 g DW | 584.1 ± 1.1 a |

| TFCalc, mg QE/100 g DW | 810.3 ± 1.3 b |

| ABTS AAaq, mg TE/100 g DW | 3190.4 ± 1.7 b |

| ABTS AAalc, mg TE/100 g DW | 1291.9 ± 4.0 a |

| DPPH AAaq, mg TE/100 g DW | 485.3 ± 1.2 a |

| DPPH AAalc, mg TE/100 g DW | 583.2 ± 0.7 b |

| Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) | Mineral Content, mg/kg DW | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium | Potassium | Magnesium | Calcium | Manganese | Iron | |

| 217.5 ± 9.6 | 29,766.3 ± 46 | 2442.3 ± 21 | 23,025.0 ± 37 | 47.0 ± 1.8 | 97.0 ± 3.2 | |

| Amino Acids, g/100 g DW | Value |

|---|---|

| Aspartic acid | 1.95 ± 0.06 |

| Threonine * | 0.64 ± 0.02 |

| Serine | 0.74 ± 0.01 |

| Glutamic * | 1.91 ± 0.08 |

| Proline | 1.01 ± 0.06 |

| Glycine | 0.84 ± 0.04 |

| Alanine | 0.75 ± 0.04 |

| Valine * | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| Cysteine | 0.22 ± 0.01 |

| Methionine * | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| Isoleucine * | 0.75 ± 0.05 |

| Leucine * | 0.97 ± 0.08 |

| Tyrosine | 0.64 ± 0.06 |

| Phenylalanine * | 0.84 ± 0.07 |

| Lysine | 0.95 ± 0.08 |

| Histidine * | 0.63 ± 0.06 |

| Arginine | 0.87 ± 0.09 |

| ∑FAAs | 14.93 ± 0.86 |

| ∑INM | 1.95 ± 0.14 |

| ∑NEAAs | 8.05 ± 0.61 |

| ∑EAAs | 6.88 ± 0.52 |

| ∑IAAs | 4.58 ± 0.09 |

| ∑GAAs | 13.01 ± 0.75 |

| ∑AAsK | 2.23 ± 0.05 |

| ∑AAsP | 14.93 ± 0.86 |

| Physicochemical Indices | Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | |

| PCY, % | 6.27 ± 0.25 a | 8.76 ± 0.25 e | 6.08 ± 0.20 a | 7.33 ± 0.31 c | 6.75 ± 0.24 b | 9.21 ± 0.35 e | 7.14 ± 0.26 d | 9.56 ± 0.39 f |

| PC, % | 76.21 ± 0.60 a | 83.45 ± 0.87 c | 83.52 ± 0.53 d | 85.61 ± 0.77 f | 77.32 ± 0.81 b | 86.67 ± 0.67 g | 85.51 ± 0.60 e | 91.21 ± 0.77 h |

| AC, % | 0.39 ± 0.02 a | 0.44 ± 0.01 b | 0.42 ± 0.02 a | 0.46 ± 0.03 c | 0.47 ± 0.02 d | 0.51 ± 0.04 d | 0.48 ± 0.02 d | 0.53 ± 0.05 d |

| FC, % | 1.07 ± 0.05 a | 1.08 ± 0.07 a | 1.12 ± 0.08 a | 1.17 ± 0.18 a | 1.10 ± 0.06 a | 1.15 ± 0.10 a | 1.14 ± 0.09 a | 1.23 ± 0.19 a |

| Titratable acidity, % expressed in lactic acid | 1.15 ± 0.02 c | 1.40 ± 0.01 g | 1.26 ± 0.02 e | 1.57 ± 0.02 h | 1.10 ± 0.01 a | 1.22 ± 0.01 d | 1.12 ± 0.01 b | 1.27 ± 0.01 f |

| Titratable acidity, % expressed in citric acid | 0.81 ± 0.01 a | 1.03 ± 0.01 f | 0.89 ± 0.01 d | 1.12 ± 0.01 g | 0.78 ± 0.01 a | 0.86 ± 0.01 c | 0.83 ± 0.03 b | 0.91 ± 0.02 e |

| pH, c.u. | 4.24 ± 0.02 c | 4.15 ± 0.02 a | 4.29 ± 0.02 d | 4.16 ± 0.01 b | 4.50 ± 0.01 g | 4.37 ± 0.02 f | 4.53 ± 0.01 h | 4.31 ± 0.02 e |

| aw, c.u. | 0.775 ± 0.001 c | 0.770 ± 0.001 a | 0.772 ± 0.001 d | 0.773 ± 0.002 d | 0.773 ± 0.002 d | 0.773 ± 0.001 d | 0.771 ± 0.001 b | 0.777 ± 0.002 e |

| PD, % | 78.15 ± 0.49 e | 84.51 ± 0.32 h | 74.26 ± 0.34 c | 80.72 ± 0.47 g | 70.89 ± 0.44 a | 78.71 ± 0.48 f | 73.49 ± 0.22 b | 77.57 ± 0.20 d |

| Indices | Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | |

| L* | 52.30 ± 0.23 d | 53.97 ± 0.18 g | 48.26 ± 0.29 a | 52.21 ± 0.24 e | 53.09 ± 0.39 f | 50.26 ± 0.28 b | 51.02 ± 0.23 c | 51.39 ± 0.45 c |

| a* | −19.04 ± 0.22 f | −15.07 ± 0.23 b | −17.14 ± 0.22 d | −13.17 ± 0.33 a | −22.27 ± 0.35 g | −15.15 ± 0.22 c | −22.80 ± 0.19 g | −17.55 ± 0.32 e |

| b* | 36.12 ± 0.39 d | 36.24 ± 0.45 d | 32.24 ± 0.41 b | 32.14 ± 0.35 b | 44.26 ± 0.49 f | 32.09 ± 0.25 a | 40.05 ± 0.18 e | 35.83 ± 0.24 c |

| −a*/b* | −0.53 ± 0.01 e | −0.41 ± 0.01 a | −0.53 ± 0.01 e | −0.41 ± 0.01 a | −0.50 ± 0.01 c | −0.47 ± 0.01 d | −0.57 ± 0.01 f | −0.49 ± 0.01 b |

| C* | 40.83 ± 0.22 f | 39.25 ± 0.51 d | 36.51 ± 0.49 c | 34.73 ± 0.47 a | 49.55 ± 0.56 h | 35.49 ± 0.34 b | 46.08 ± 0.26 g | 39.90 ± 0.36 e |

| h*, ° | 117.8 ± 0.6 f | 112.6 ± 0.2 b | 118.0 ± 0.1 f | 112.3 ± 0.4 a | 116.7 ± 0.2 e | 115.3 ± 0.2 c | 119.6 ± 0.2 g | 116.1 ± 0.4 d |

| ΔE* | - | 4.31 ± 0.51 | - | 5.60 ± 0.23 | - | 14.38 ± 0.26 | - | 6.75 ± 0.11 |

| Sample images |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Indices | Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | |

| Chl a, mg/100 g DW | 12.73 ± 0.75 e | 3.67 ± 0.58 a | 11.91 ± 0.59 e | 4.25 ± 0.55 b | 13.57 ± 0.78 e | 7.52 ± 0.83c | 14.25 ± 0.58 f | 8.09 ± 0.81 d |

| Chl b, mg/100 g DW | 4.03 ± 0.25 e | 1.40 ± 0.66 a | 4.10 ± 0.40 e | 1.83 ± 0.25 b | 6.08 ± 0.88 f | 3.64 ± 0.51 d | 6.10 ± 0.50 f | 3.53 ± 0.45 c |

| TChl, mg/100 g DW | 16.76 ± 0.72 e | 5.07 ± 0.45 a | 16.01 ± 0.43 e | 6.08 ± 0.10 b | 19.65 ± 0.23 f | 11.16 ± 0.14 c | 20.35 ± 0.07 g | 11.62 ± 0.14 d |

| CC, mg/100 g DW | 3.07 ± 0.21 h | 0.60 ± 0.20 b | 2.93 ± 0.15 g | 0.67 ± 0.06 c | 2.83 ± 0.15 f | 1.13 ± 0.06 d | 2.40 ± 0.10 e | 0.09 ± 0.10 a |

| TPCaq, mg GAE/100 g DW | 1347.3 ± 6.6 a | 1965.0 ± 6.0 d | 1355.7 ± 4.3 a | 2553.8 ± 8.4 f | 1589.8 ± 5.6 b | 2237.3 ± 6.3 e | 1680.7 ± 4.3 c | 3118.8 ± 10.9 g |

| TFCaq, mg QE/100 g DW | 261.54 ± 5.27 b | 428.28 ± 1.20 d | 241.79 ± 2.71 a | 693.77 ± 1.91 g | 395.05 ± 1.55 c | 649.27 ± 1.78 f | 487.40 ± 1.30 e | 945.29 ± 1.12 h |

| ABTS AAaq, mg TE/100 g DW | 1699.3 ± 5.3 a | 1771.5 ± 5.6 a,b,c | 1709.9 ± 3.3 a,b | 1911.4 ± 4.6 e | 1849.3 ± 3.7 a,b,c,d | 1934.0 ± 6.8 d | 1860.6 ± 3.4 d | 2194.9 ± 6.8 f |

| DPPH AAaq, mg TE/100 g DW | 397.16 ± 6.81 a | 360.68 ± 2.04 a | 406.31 ± 3.73 a | 382.56 ± 4.31 a | 417.18 ± 4.59 a,b | 414.37 ± 5.41 b | 421.97 ± 2.49 b | 430.70 ± 3.11 b |

| TPCalc, mg GAE/100 g DW | 2107.2 ± 7.11 a | 2250.4 ± 3.8 b | 2488.7 ± 7.6 c | 2585.3 ± 6.3 c,d,e | 2663.9 ± 2.6 f | 2669.0 ± 4.1 f | 2535.2 ± 3.7 c,d,e,f | 3045.3 ± 5.1 g |

| TFCalc, mg QE/100 g DW | 782.36 ± 2.21 b | 795.33 ± 3.11 d | 784.72 ± 2.76 b,c | 798.96 ± 2.03 e | 756.78 ± 5.78 a | 759.98 ± 4.32 a | 738.03 ± 3.16 a | 901.69 ± 2.87 f |

| ABTS AAalc, mg TE/100 g DW | 1304.4 ± 3.3 b | 1259.6 ± 4.2 b | 1447.1 ± 2.4 e,f | 1393.7 ± 4.6 d | 1462.5 ± 4.4 g | 1201.0 ± 2.2 a | 1417.0 ± 3.4 e | 1376.6 ± 2.7 c |

| DPPH AAalc, mg TE/100 g DW | 607.34 ± 1.5 a,b | 523.60 ± 1.61 a | 605.23 ± 1.41 a,b | 558.14 ± 1.82 b | 588.0 ± 2.06 a,b | 515.10 ± 1.61 a,b | 608.98 ± 3.67 a,b | 573.73 ± 2.01 b |

| Indices | Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | |

| Hardness, g | 29.76 ± 0.70 c | 49.19 ± 0.37 g | 28.19 ± 0.23 c | 36.32 ± 0.51 d | 27.15 ± 0.69 b | 43.66 ± 0.60 f | 25.50 ± 0.73 a | 37.90 ± 0.23 e |

| Adhesivity, g‧s | 16.69 ± 0.59 b | 67.40 ± 0.76 h | 22.38 ± 0.68 d | 47.39 ± 0.65 f | 13.22 ± 0.73 a | 36.33 ± 0.39 e | 18.56 ± 0.40 c | 53.59 ± 0.51 g |

| Springiness, % | 1.022 ± 0.003 e | 0.999 ± 0.002 c | 0.995 ± 0.003 a | 1.000 ± 0.002 c | 0.999 ± 0.003 c | 1.001 ± 0.002 c | 0.999 ± 0.003 a,b,c | 0.998 ± 0.002 b |

| Cohesiveness, % | 0.319 ± 0.014 a | 0.305 ± 0.005 a | 0.354 ± 0.021 d | 0.492 ± 0.012 f | 0.323 ± 0.011 a,b | 0.363 ± 0.021 e | 0.333 ± 0.019 b,c,d | 0.524 ± 0.013 g |

| Gumminess, g | 9.57 ± 0.52 c | 14.91 ± 0.25 d | 9.87 ± 0.33 c | 17.86 ± 0.51 f | 8.62 ± 0.41 a | 15.67 ± 0.40 e | 8.95 ± 0.56 a,b | 19.65 ± 0.51 g |

| Indices | Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | |

| FoC, % | 85.19 ± 0.43 f | 88.01 ± 0.55 h | 84.47 ± 0.28 d | 87.88 ± 0.36 g | 76.35 ± 0.30 b | 82.80 ± 0.26 e | 73.16 ± 0.40 a | 79.64 ± 0.33 c |

| FoS, % | 86.30 ± 0.30 f | 88.87 ± 0.30 h | 84.97 ± 0.20 d | 87.05 ± 0.30 g | 83.97 ± 0.19 c | 85.92 ± 0.32 e | 81.81 ± 0.18 a | 83.92 ± 0.19 b |

| EA, % | 43.09 ± 0.21 a | 49.34 ± 0.24 c | 43.70 ± 0.27 b | 50.84 ± 0.17 d | 52.39 ± 0.35 e | 55.80 ± 0.27 g | 54.50 ± 0.32 f | 57.51 ± 0.27 h |

| ES, % | 40.19 ± 0.77 a | 52.72 ± 0.96 d | 45.80 ± 0.47 c | 57.03 ± 0.67 g | 44.37 ± 0.70 b | 56.04 ± 0.61 f | 54.46 ± 0.17 e | 62.17 ± 0.34 h |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gurev, A.; Bulgaru, V.; Ciugureanu, I.; Netreba, N.; Dragancea, V.; Dianu, I.; Sandu, I.; Mazur, M.; Mitina, T.; Bandarenco, N.; et al. Effect of Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties, Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant Activity and Functional Properties of Alfalfa Protein Concentrates. Foods 2025, 14, 4309. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244309

Gurev A, Bulgaru V, Ciugureanu I, Netreba N, Dragancea V, Dianu I, Sandu I, Mazur M, Mitina T, Bandarenco N, et al. Effect of Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties, Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant Activity and Functional Properties of Alfalfa Protein Concentrates. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4309. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244309

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurev, Angela, Viorica Bulgaru, Iana Ciugureanu, Natalia Netreba, Veronica Dragancea, Irina Dianu, Iuliana Sandu, Mihail Mazur, Tatiana Mitina, Nadejda Bandarenco, and et al. 2025. "Effect of Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties, Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant Activity and Functional Properties of Alfalfa Protein Concentrates" Foods 14, no. 24: 4309. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244309

APA StyleGurev, A., Bulgaru, V., Ciugureanu, I., Netreba, N., Dragancea, V., Dianu, I., Sandu, I., Mazur, M., Mitina, T., Bandarenco, N., & Ghendov-Mosanu, A. (2025). Effect of Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties, Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant Activity and Functional Properties of Alfalfa Protein Concentrates. Foods, 14(24), 4309. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244309