Effects of Different Pretreatments on the Nutrition, Flavor and Sensory Evaluation of Lactobacilli-Fermented Peach Beverages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain, Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Peach Material and Sample Preparation

2.3. Fermentation Process

2.4. Viable Cell and pH Measurement

2.5. Determination of Total Phenol Content and Antioxidant Activity

2.6. Determination of Sugars and Organic Acids by HPLC

2.7. Determination of Polyphenols by HPLC

2.8. Determination of Carotenoids by HPLC

2.9. Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds by GC-MS

2.10. Odor Activity Values (OAVs)

2.11. Sensory Evaluation

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Viable Counts, pH Values, Total Phenol and Antioxidant Activity

3.2. Sugars and Organic Acids

3.3. Polyphenols

3.4. Carotenoids

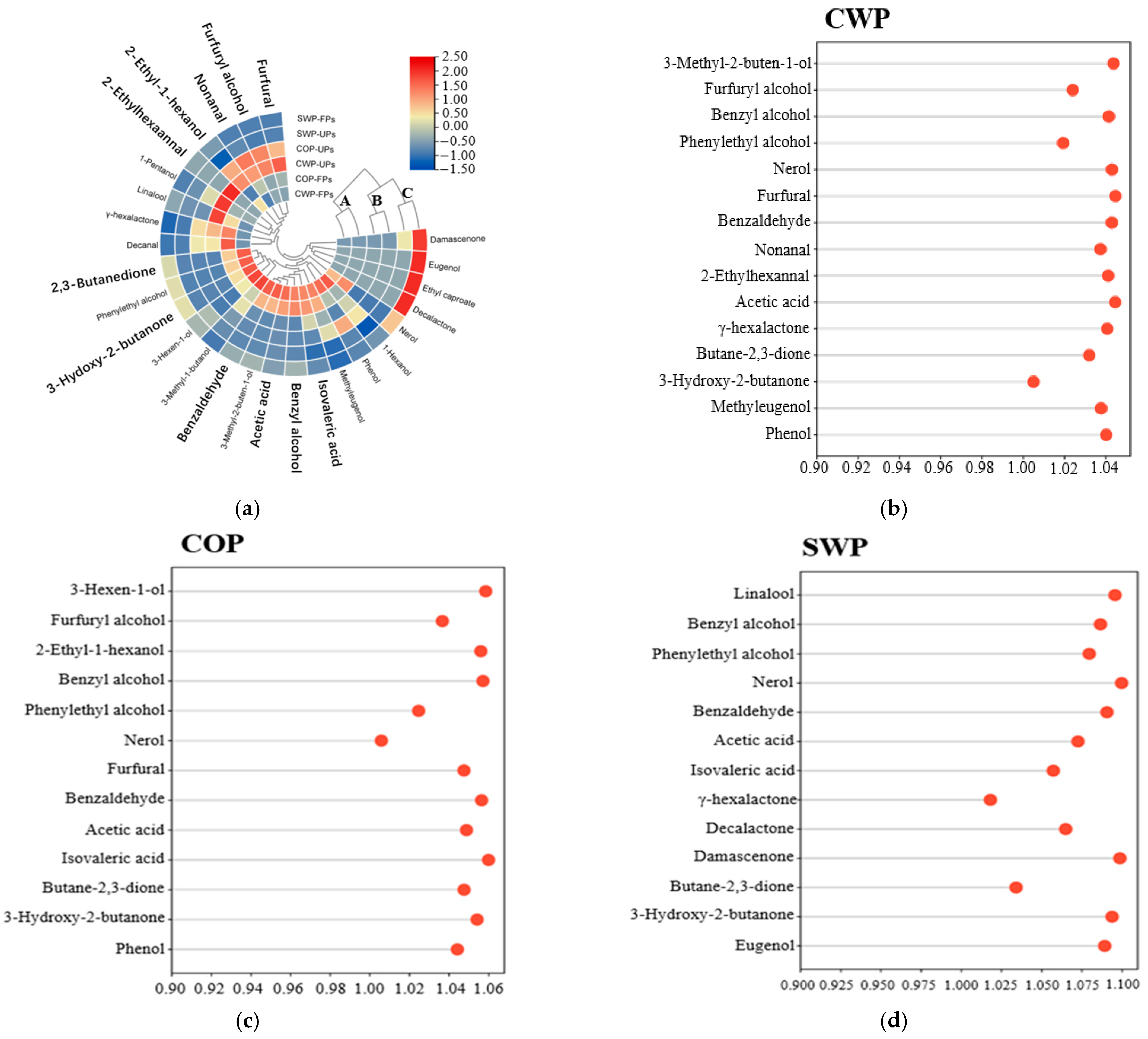

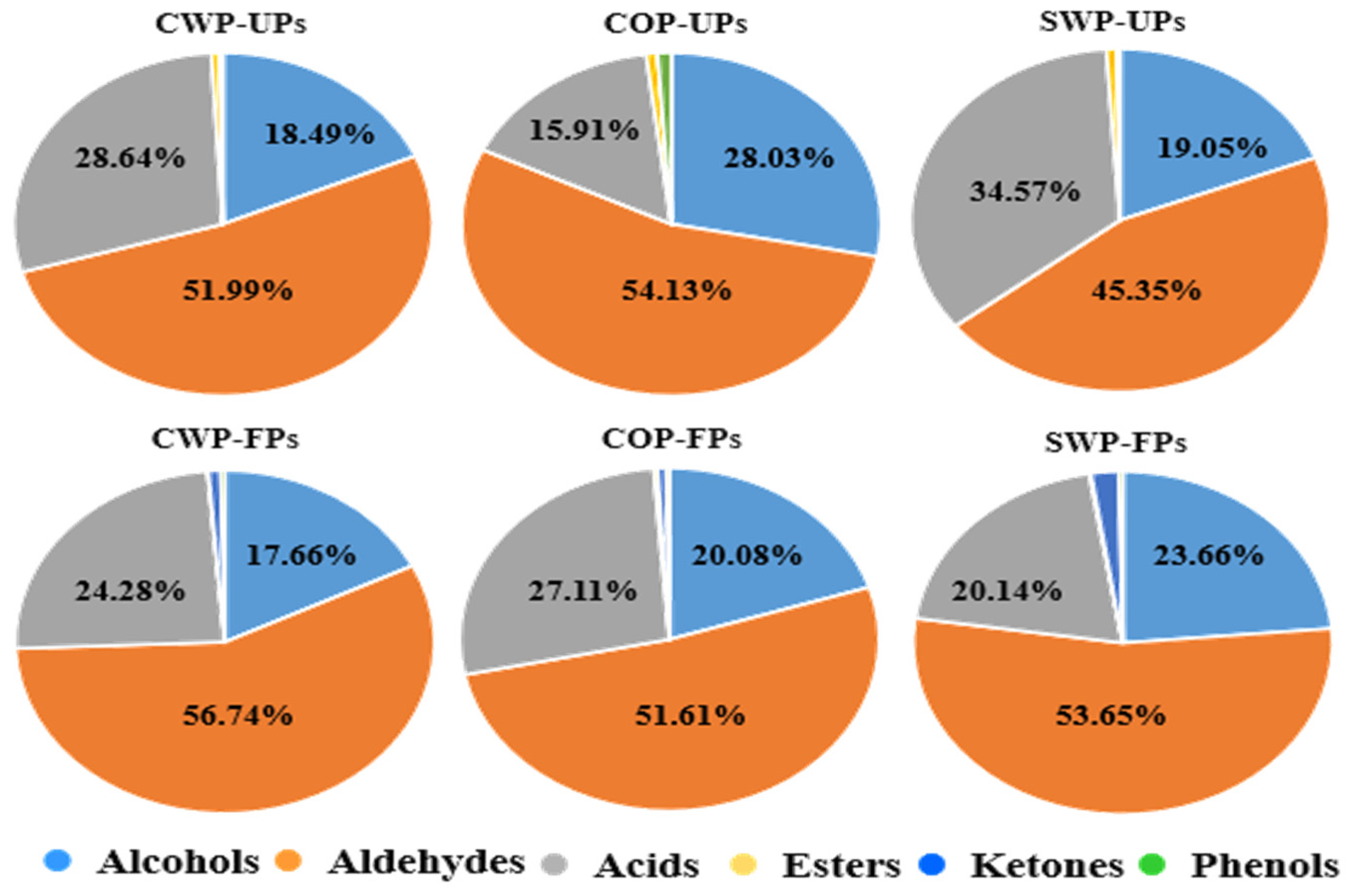

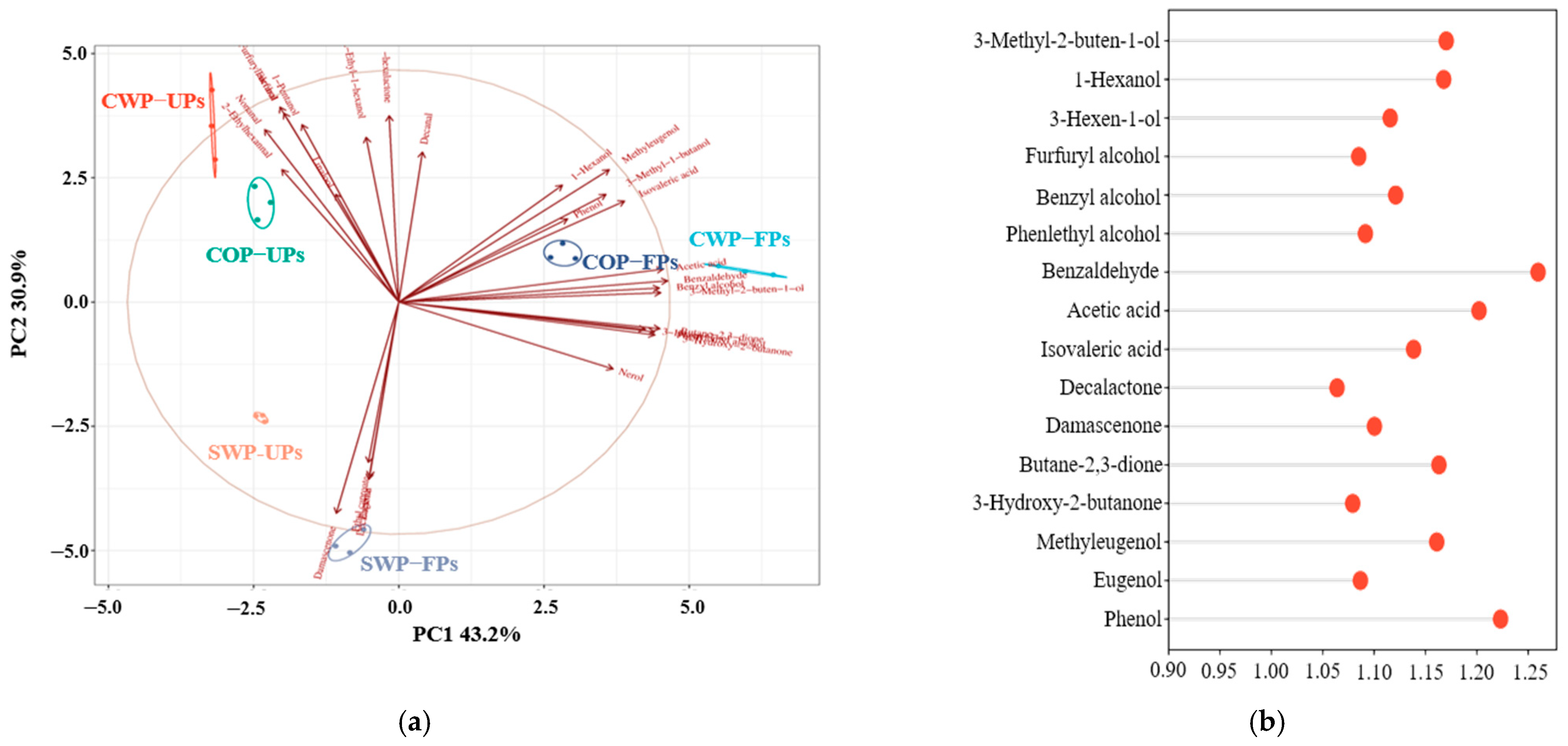

3.5. VOCs

3.6. Analysis of the OAVs

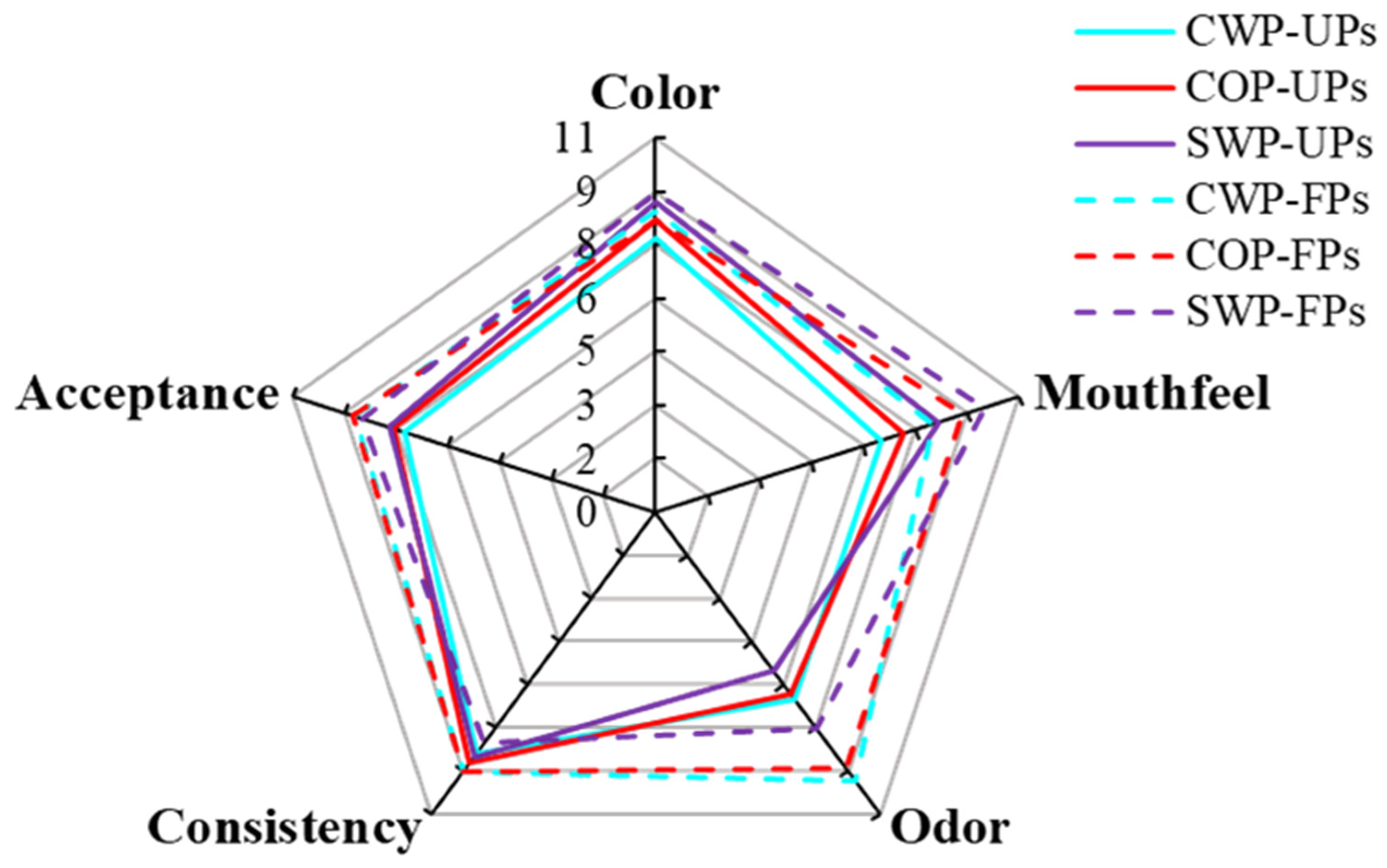

3.7. Sensory Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CWP | Peach fruit crushing into puree with peel |

| COP | Peach fruit crushing into puree without peel |

| SWP | Peach fruit squeezing into juice with peel |

| FPs | Fermented peach sample |

| UPs | Unfermented peach sample |

References

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cui, M.; Hu, Y.; Yin, R.; Ma, X.; Niu, J.; Cheng, W.; et al. Enhancing physicochemical properties, organic acids, antioxidant capacity, amino acids and volatile compounds for ‘Summer Black’ grape juice by lactic acid bacteria fermentation. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 209, 116791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cao, W.; Liu, R.; Wu, M.; Ge, Q.; Yu, H. Exploring Jiangshui-originated probiotic lactic acid bacteria as starter cultures: Functional properties and fermentation performances in pear juice. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, S.; Sarkar, P.; Sahoo, D.; Rai, A. Potential of fermented foods and their metabolites in improving gut microbiota function and lowering gastrointestinal inflammation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 4058–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, C.; Jeppesen, P.; Hermansen, K.; Gregersen, S. The impact of an 8-week supplementation with fermented and non-fermented aronia berry pulp on cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with Type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea, M.B.; Santos, D.C.D.; Oliveira Filho, J.G.D.; Ores, J.D.C.; Takeuchi, K.P.; Lemes, A.C. A review of nondairy kefir products: Their characteristics and potential human health benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1536–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A.D.; Frostell, B.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Protein efficiency per unit energy and per unit greenhouse gas emissions: Potential contribution of diet choices to climate change mitigation. Food Policy 2011, 36, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermented Plant-Based Alternatives Market-A Global and Regional Analysis: Focus on Applications, Products, Patent Analysis, and Country Analysis-Analysis and Forecast, 2019–2026. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5359984/fermented-plant-based-alternatives-market-a (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Manzoor, M.; Anwar, F.; Mahmood, Z.; Rashid, U.; Ashraf, M. Variation in minerals, phenolics and antioxidant activity of peel and pulp of different varieties of peach (Prunus persica L.) fruit from Pakistan. Molecules 2012, 17, 6491–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, B.; Jooyandeh, H.; Hojjati, M.; Sheikhjan, M. Evaluation of probiotic, safety, and anti-pathogenic properties of Levilactobacillus brevis HL6, and its potential application as bio-preservatives in peach juice. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 191, 115601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Jafarpour, D.; Jouki, M. Improving bioactive properties of peach juice using Lactobacillus strains fermentation: Antagonistic and anti-adhesion effects, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, and Maillard reaction inhibition. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, Z. Changes in nutritional composition, volatile organic compounds and antioxidant activity of peach pulp fermented by lactobacillus. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, Z. Nutritional and flavor properties of grape juice as affected by fermentation with lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Prop. 2021, 24, 906–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, Z.; Jiao, Z. Characterization of strawberry purees fermented by Lactobacillus spp. based on nutrition and flavor profiles using LC-TOF/MS, HS-SPME-GC/MS and E-nose. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 189, 115457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Bai, Y.; Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Gänzle, M. Metabolism of phenolic compounds by Lactobacillus spp. during fermentation of cherry juice and broccoli puree. Food Micro 2015, 46, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudke, C.R.M.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Ferreira, S.R.S. From biorefinery to food product design: Peach (Prunus persica) by-products deserve attention. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2023, 16, 1197–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanovic, B.T.; Mitic, S.S.; Stojanovic, G.S.; Mitic, M.N.; Kostic, D.A.; Paunovic, D.D.; Arsic, B.B. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of pulp and peel from peach and nectarine fruits. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobo 2016, 44, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Meng, D.; Yue, T.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Z. Effect of the apple cultivar on cloudy apple juice fermented by a mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Lactobacillus fermentum. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 127992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yang, W.; Lv, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, Z. Effects of different pretreatments on physicochemical properties and phenolic compounds of hawthorn wine. Cyta-J. food 2020, 18, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Chi, X.; Dong, Q.; Hu, F. Antioxidants screening in Limonium aureum by optimized on-line HPLC-DPPH assay. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 67, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Jiao, Z. Profiles of sugar and organic acid of fruit juices: A comparative study and implication for authentication. J. Food Qual. 2020, 2020, 7236534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abliz, A.; Liu, J.; Mao, L.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Effect of dynamic high pressure microfluidization treatment on physical stability, microstructure on physical stability, microstructure and carotenoids release of sea buckthorn juice. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 135, 110277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Qi, J.; Jin, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Xu, H. Influence of fruit maturity and lactic fermentation on physicochemical properties, phenolics, volatiles, and sensory of mulberry juice. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Tang, F.; Shan, C. Influence of lactic acid bacteria on physicochemical indexes, sensory and flavor characteristics of fermented sea buckthorn juice. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hlaing, M.; Glagovskaia, O.; Augustin, M.; Terefe, N. Fermentation by probiotic Lactobacillus gasseri strains enhances the carotenoid and fiber contents of carrot juice. Foods 2020, 9, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikmetas, D.; Nemli, E.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Apak, R.; Bener, M.; Zhang, W.; Jia, N.; Zhao, C.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Lactic acid bacterial culture selection for orange pomace fermentation and its potential use in functional orange juice. Acs Omega 2025, 10, 11038–11053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Yang, N.; Jiang, T.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Fermentation of kiwifruit juice from two cultivars by probiotic bacteria: Bioactive phenolics, antioxidant activities and flavor volatiles. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 11455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jiang, T.; Liu, N.; Wu, C.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Biotransformation of phenolic profiles and improvement of antioxidant capacities in jujube juice by select lactic acid bacteria. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Peng, F.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, M. Fermentation of Chinese sauerkraut in pure culture and binary co-culture with Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus plantarum. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 59, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirlini, M.; Ricci, A.; Galaverna, G.; Lazzi, C. Application of lactic acid fermentation to elderberry juice: Changes in acidic and glucidic fractions. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 118, 108779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasila, H.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Ahmad, I.; Ahmad, S. Peel effects on phenolic composition, antioxidant activity, and making of pomegranate juice and wine. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, C1166–C1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, F.; Giménez, R.; Aubert, C.; Chalot, G.; Betrán, J.; Gogorcena, Y. Phenolic, sugar and acid profiles and the antioxidant composition in peel and pulp of peach fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 62, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, W.; Yin, X.; Su, M.; Sun, C.; Li, X.; Chen, K. Phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of different peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] cultivars in China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 5762–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, C.; Chalot, G. Physicochemical characteristics, vitamin C, and polyphenolic composition of four European commercial blood-flesh peach cultivars (Prunus persica L. Batsch). J. Food Compo. Anal. 2020, 86, 103337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cao, J.; Weibo, J. Evaluation and comparison of Vitamin C, phenolic compounds, antioxidant properties and metal chelating activity of pulp and peel from selected peach cultivars. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lan, Q.; Liu, X.; Cai, Z.; Zeng, R.; Tang, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, C.; Hu, B.; Laghi, L. Effects of pretreatment methods on the flavor profile and sensory characteristics of Kiwi wine based on 1H NMR, GC-IMS and E-tongue. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 203, 116375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Meng, Y. Polyphenols in fermented apple juice: Beneficial effects on human health. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 76, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Shah, N.P. Lactic acid bacterial fermentation modified phenolic composition in tea extracts and enhanced their antioxidant activity and cellular uptake of phenolic compounds following in vitro digestion. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 20, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, F.; Curiel, J.; Muñoz, R. Improvement of the fermentation performance of Lactobacillus plantarum by the flavanol catechin is uncoupled from its degradation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fan, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, K.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Fang, W.; Zhu, G.; Wang, L. Characterizing of carotenoid diversity in peach fruits affected by the maturation and varieties. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 113, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchi, R.; Vendramin, E.; Zanon, L.; Scalabrin, S.; Cipriani, G.; Verde, I.; Vizzotto, G.; Morgante, M. Three distinct mutational mechanisms acting on a single gene underpin the origin of yellow flesh in peach. Plant J. 2013, 76, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeencio, S.; Verkempinck, S.; Bernaerts, T.; Reineke, K.; Hendrickx, M.; Loey, A. Impact of processing on the production of a carotenoid-rich Cucurbita maxima cv. Hokkaido pumpkin juice. Food Chem. 2022, 380, 132191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohinejad, S.; Everett, D.; Oey, I. Effect of pulsed electric field processing on carotenoid extractability of carrot puree. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2014, 49, 2120–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Barba, F.J.; Remize, F.; Garcia, C.; Fessard, A.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Montesano, D.; Mel’endez-Martínez, A.J. The impact of fermentation processes on the production, retention and bioavailability of carotenoids: An overview. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2020, 99, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.; Aeri, V. Enhancement of lutein content in Calendula officinalis Linn. By solid-state fermentation with Lactobacillus species. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 4794–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenta-López, R.; Guerrero, I.; Huerta, S. Astaxanthin extraction from shrimp waste by lactic fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis of the carotenoprotein complex. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsokoti, L.; Panozzo, A.; Tongonya, J.; Kebede, B.; Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Carotenoid stability and lipid oxidation during storage of low-fat carrot and tomato based systems. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 80, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordi, R.; Ademosun, O.; Ajanaku, C.; Olanrewaju, I.; Walton, J. Free radical mediated oxidative degradation of carotenes and xanthophylls. Molecules 2020, 25, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carail, M.; Caris-Veyrat, C. Carotenoid oxidation products: From villain to saviour? Pure Appl. Chem. 2006, 78, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, J.; Qin, M.; Ntezimana, B.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Ni, D. Oxidation of tea polyphenols promotes chlorophyll degradation during black tea fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Fang, Z. Modern technologies for extraction of aroma compounds from fruit peels: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1284–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lu, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, Z.; Tian, H. Influence of 4 lactic acid bacteria on the flavor profile of fermented apple juice. Food Biosci. 2019, 27, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Yang, X.; Ji, Y.; Guan, Y. Effect of starter cultures mixed with different autochthonous lactic acid bacteria on microbial, metabolome and sensory properties of Chinese northeast sauerkraut. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wu, M.; Li, Y.; Qayyum, N.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C. The effect of different pretreatment methods on jujube juice and lactic acid bacteria-fermented jujube juice. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 181, 114692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, R.D.; Filannino, P.; Gobbetti, M. Lactic acid fermentation drives the optimal volatile flavor-aroma profile of pomegranate juice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 248, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thierry, A.; Richoux, R.; Kerjean, J.; Lortal, S. A simple screening method for isovaleric acid production by Propionibacterium freudenreichii in Swiss cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2004, 14, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Hu, Z. Elucidating the effects of Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation on the aroma profiles of pasteurized litchi juice using multi-scale molecular sensory science. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Song, H.; Zou, T. Screening of the volatile compounds in fresh and thermally treated watermelon juice via headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-olfactory-mass spectrometry analysis. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 137, 110478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorau, R.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Jensen, P.; Solem, C. Efficient production of α-acetolactate by whole cell catalytic transformation of fermentation-derived pyruvate. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Feng, J.; Chen, Q.; Lin, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, J.; Tan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Comparative volatiles profiling in milk-flavored white tea and traditional white tea Shoumei via HS-SPME-GC-TOFMS and OAV analyses. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, R.D.; Veras, F.F.; Hernandes, K.C.; Bach, E.; Passaglia, L.M.P.; Zini, C.A.; Brandelli, A.; Welke, J.E. Genomic analysis reveals genes that encode the synthesis of volatile compounds by a Bacillus velezensis-based biofungicide used in the treatment of grapes to control Aspergillus carbonarius. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 415, 110644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yu, M.; Liu, C.; Gao, X.; Song, H. Sensory-directed characterization of key odor-active compounds in fermented milk. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 126, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerny, M.; Christlbauer, M.; Christlbauer, M.; Fischer, A.; Granvogl, M.; Hammer, M.; Hartl, C.; Hernandez, N.; Schieberle, P. Re-investigation on odour thresholds of key food aroma compounds and development of an aroma language based on odour qualities of defined aqueous odorant solutions. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 228, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Deng, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, J. Characterization of the major aroma-active compounds in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch) by gas chromatography-olfactometry, flame photometric detection and molecular sensory science approaches. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Ochiai, N.; Yamazaki, Y.; Sasamoto, K. Solvent-assisted stir bar sorptive extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with simultaneous olfactometry for the characterization of aroma compounds in Japanese Yamahai-brewed sake. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Wahia, H.; Phyllis, O.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Qiao, X.; Ma, H. Vacuum freeze drying combined with catalytic infrared drying to improve the aroma quality of chives: Potential mechanisms of their formation. Food Chem. 2024, 461, 140880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gemert, L.J. Complilations of Odour Threshold Values in Air, Water and Other Media; Van SettenKwadraat: Houten, The Netherlands, 2003; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Yin, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Bie, S.; et al. Discrimination and characterization of the volatile organic compounds of Acori tatarinowii rhizome based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and headspace solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Ara. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | CWP | COP | SWP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | |

| Viable counts (log CFU/mL) | ND | 9.30 ± 0.19 a | ND | 9.31 ± 0.05 a | ND | 9.24 ± 0.07 a |

| pH | 4.81 ± 0.00 c | 3.82 ± 0.01 f | 4.82 ± 0.00 b | 3.85 ± 0.00 e | 4.85 ± 0.01 a | 3.86 ± 0.00 d |

| Total phenols (μg/mL) | 122.11 ± 7.37 bc | 145.20 ± 4.21 a | 104.61 ± 1.45 d | 123.63 ± 6.43 bc | 117.11 ± 0.62 c | 125.7 ± 0.44 b |

| Antioxidant activity (μg VC/mL) | 71.06 ± 0.10 d | 96.19 ± 2.32 a | 61.14 ± 0.10 e | 89.41 ± 0.83 b | 59.15 ± 0.66 e | 76.67 ± 2.39 c |

| Categories | CWP | COP | SWP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | |

| Sugars | ||||||

| Sucrose | 49.05 ± 0.35 a | 48.75 ± 0.50 a | 46.87 ± 0.21 b | 46.83 ± 0.17 b | 49.15 ± 0.87 a | 49.02 ± 1.35 a |

| Glucose | 7.97 ± 0.07 a | 5.91 ± 0.14 c | 8.15 ± 0.12 a | 6.03 ± 0.05 c | 7.55 ± 0.07 b | 5.34 ± 0.16 d |

| Fructose | 9.43 ± 0.10 a | 8.56 ± 0.17 b | 9.18 ± 0.35 a | 8.32 ± 0.03 b | 8.95 ± 0.13 b | 8.62 ± 0.26 c |

| Sorbitol | 4.34 ± 0.08 ab | 4.41 ± 0.03 a | 3.34 ± 0.06 c | 3.23 ± 0.02 c | 4.26 ± 0.11 b | 4.35 ± 0.11 ab |

| Total sugars | 70.79 ± 0.58 a | 67.64 ± 0.51 b | 67.56 ± 0.03 b | 64.50 ± 0.11 c | 69.90 ± 1.17 a | 67.32 ± 1.11 c |

| Organic acids | ||||||

| Quininic acid | 1.01 ± 0.04 c | 1.59 ± 0.03 a | 0.91 ± 0.04 d | 1.21 ± 0.02 b | 0.96 ± 0.01 cd | 1.54 ± 0.08 a |

| Malic acid | 2.22 ± 0.26 a | ND | 2.37 ± 0.06 a | ND | 2.36 ± 0.13 a | ND |

| Shikimic acid | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b |

| Lactic acid | ND | 8.60 ± 0.07 a | ND | 7.55 ± 0.08 c | ND | 8.17 ± 0.09 b |

| Citric acid | 0.92 ± 0.07 a | 0.78 ± 0.02 b | 0.92 ± 0.03 a | 0.73 ± 0.02 bc | 0.94 ± 0.01 a | 0.71 ± 0.02 c |

| Fumaric acid | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | ND | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | ND | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | ND |

| Total acids | 4.12 ± 0.15 d | 10.99 ± 0.10 a | 4.21 ± 0.12 d | 9.51 ± 0.08 c | 4.27 ± 0.12 d | 10.43 ± 0.08 b |

| Categories | CWP | COP | SWP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | |

| Phenolic acid | ||||||

| Protocatechuic acid | 9.88 ± 0.73 ab | 3.75 ± 0.42 d | 10.30 ± 0.33 a | 4.06 ± 0.82 d | 8.75 ± 0.73 b | 5.61 ± 0.38 c |

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.35 ± 0.09 c | 7.59 ± 0.70 a | 0.38 ± 0.02 c | 6.91 ± 0.30 b | 0.37 ± 0.01 c | 7.13 ± 0.07 ab |

| Vanillic acid | 0.34 ± 0.03 c | 1.25 ± 0.04 a | 0.33 ± 0.01 c | 1.08 ± 0.06 b | 0.36 ± 0.00 c | 1.19 ± 0.06 a |

| p-coumaric acid | 0.15 ± 0.02 c | 0.23 ± 0.00 a | 0.12 ± 0.02 d | 0.17 ± 0.01 b | 0.11 ± 0.01 d | 0.17 ± 0.01 b |

| Total phenolic acids | 10.71 ± 0.84 bc | 12.82 ± 0.89 ab | 11.13 ± 0.35 bc | 12.22 ± 1.09 ab | 9.59 ± 0.74 c | 14.11 ± 0.51 a |

| Flavonols | ||||||

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | 2.42 ± 0.41 b | 1.36 ± 0.14 c | 2.74 ± 0.09 ab | 1.20 ± 0.05 c | 2.88 ± 0.08 a | 1.31 ± 0.12 c |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 2.74 ± 0.50 c | 3.93 ± 0.29 b | 3.31 ± 0.12 c | 3.99 ± 0.31 b | 3.28 ± 0.08 c | 4.75 ± 0.34 a |

| Isorhamnetin | 0.02 ± 0.00 c | 2.12 ± 0.06 b | 0.03 ± 0.00 c | 2.26 ± 0.10 b | 0.03 ± 0.00 c | 2.44 ± 0.19 a |

| Quercetin | 0.30 ± 0.10 c | 1.14 ± 0.11 a | 0.24 ± 0.03 c | 0.95 ± 0.06 b | 0.20 ± 0.01 c | 1.21 ± 0.10 a |

| Total flavonoids | 5.48 ± 1.00 b | 8.54 ± 0.55 a | 6.32 ± 0.22 b | 8.41 ± 0.51 a | 6.40 ± 0.15 b | 9.71 ± 0.73 a |

| Flavan-3-ols | ||||||

| Catechin | 4.17 ± 0.10 b | 5.14 ± 0.10 a | 4.22 ± 0.15 b | 5.11 ± 0.08 a | 3.90 ± 0.01 c | 5.10 ± 0.09 a |

| Epicatechin | 5.44 ± 0.63 d | 8.99 ± 0.51 a | 5.35 ± 0.28 d | 6.88 ± 0.52 c | 6.02 ± 0.21 cd | 7.85 ± 0.59 b |

| Proanthocyanidin B1 | 1.39 ± 0.13 b | 3.54 ± 0.19 a | 1.09 ± 0.07 b | 3.61 ± 0.13 a | 1.24 ± 0.01 b | 3.77 ± 0.21 a |

| Total flavan-3-ols | 10.99 ± 0.79 c | 17.67 ± 0.48 a | 10.66 ± 0.23 c | 15.60 ± 0.71 b | 11.16 ± 0.20 c | 16.73 ± 0.36 ab |

| Total phenol | 27.18 ± 2.33 c | 39.03 ± 0.97 a | 28.11 ± 0.59 c | 36.23 ± 2.19 b | 27.15 ± 0.99 c | 40.55 ± 0.88 a |

| Categories | CWP | COP | SWP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | |

| Zeaxanthin | 369.62 ± 39.36 a | 238.86 ± 23.53 c | 288.28 ± 18.36 bc | 338.84 ± 19.88 ab | ND | ND |

| β-cryptoxanthin | 132.75 ± 2.09 a | 89.48 ± 8.91 c | 93.32 ± 3.30 bc | 101.61 ± 6.92 b | ND | ND |

| β-carotene | 1524.78 ± 91.38 a | 1115.87 ± 67.82 b | 1082.93 ± 14.99 b | 1134.89 ± 41.80 b | 86.33 ± 3.26 d | 79.59 ± 10.20 d |

| Total carotenoids | 2008.44 ± 57.68 a | 1444.21 ± 92.53 c | 1464.53 ± 0.06 bc | 1575.33 ± 68.60 b | 86.33 ± 3.26 d | 79.59 ± 10.20 d |

| CAS Number | Odor Threshold (μg/L) | CWP | COP | SWP | Odorant Description | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | UPs | FPs | ||||

| Alcohol | |||||||||

| 3-Mehtyl-1-butanol | 123-51-3 | 1.7 [59] | 1.19 | 2.74 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | Fruity, banana [60] |

| Furfuryl alcohol | 98-00-0 | 32 [61] | 2.22 | <1 | 2.21 | <1 | <1 | <1 | bread-like [61] |

| Linalool | 78-70-6 | 0.17 [62] | 8.32 | <1 | <1 | 3.88 | <1 | <1 | Citrus-like, bergamot-like [62] |

| Benzyl alcohol | 100-51-6 | 120 [63] | <1 | 2.81 | <1 | 2.70 | <1 | <1 | Floral, rose [63] |

| Aldehydes | |||||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | 320 [63] | <1 | 3.87 | <1 | 2.63 | <1 | <1 | Almond [64] |

| Nonanal | 124-19-6 | 1.1 [53] | 4.82 | <1 | 5.43 | 2.38 | <1 | <1 | Fat, citrus, green [53] |

| Decanal | 112-31-2 | 5 [65] | 2.59 | <1 | 2.47 | 4.71 | <1 | <1 | Sweet, orange peel, citrus, floral [65] |

| Ketones | |||||||||

| 2,3-Butanedione | 431-03-8 | 0.059 [61] | <1 | 114.24 | <1 | 67.63 | <1 | 45.65 | Buttery [61] |

| Phenols | |||||||||

| Methyleugenol | 93-15-2 | 0.068 [66] | 22.50 | 69.26 | 37.65 | 57.99 | <1 | <1 | Sweet, clove aroma [67] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, Z.; Chen, D.; Yang, W.; Jiao, Z. Effects of Different Pretreatments on the Nutrition, Flavor and Sensory Evaluation of Lactobacilli-Fermented Peach Beverages. Foods 2025, 14, 4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244303

Han Q, Liu J, Liu H, Zhang Q, Lv Z, Chen D, Yang W, Jiao Z. Effects of Different Pretreatments on the Nutrition, Flavor and Sensory Evaluation of Lactobacilli-Fermented Peach Beverages. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244303

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Qiaoyu, Jiechao Liu, Hui Liu, Qiang Zhang, Zhenzhen Lv, Dalei Chen, Wenbo Yang, and Zhonggao Jiao. 2025. "Effects of Different Pretreatments on the Nutrition, Flavor and Sensory Evaluation of Lactobacilli-Fermented Peach Beverages" Foods 14, no. 24: 4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244303

APA StyleHan, Q., Liu, J., Liu, H., Zhang, Q., Lv, Z., Chen, D., Yang, W., & Jiao, Z. (2025). Effects of Different Pretreatments on the Nutrition, Flavor and Sensory Evaluation of Lactobacilli-Fermented Peach Beverages. Foods, 14(24), 4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244303